Stuccoed in pink, green or yellow, grand neo-Renaissance and neo-Gothic buildings line the Parizká, the Avenue of Paris. Since the fall of the wall, elegant boutiques have been flourishing on this major traffic artery, which lacks none of the cachet that it had at the beginning of the century. Here the legendary ghetto of Prague was located until the renovation of the city center between 1897 and 1905. All that remains are the shadowy alleys abandoned by the growing number of Jews at the time of their emancipation in 1850. Only the poorest and most pious stayed in the former Jewish quarter, “with its shelves of old clothes, scrap metals, and other nameless things on display”, as Apollinaire wrote in Le Passant de Prague (The Wandering Jew). It is the smallest district of old Prague, covering an area scarcely 86000 square feet, and there is not a single tree except for those in the old cemetery. Deserted by its former inhabitants, these small, dirty islands of residential space were gradually invaded by the poor, the marginalized, and the city’s prostitues. In the first years of the twentieth century, the bordellos with their red lanterns and the disreputable taverns multiplied among the places of worship and buildings still inhabited by Orthodox Jews. On Shabbat evenings, the prayers and sacred songs of the Jews mingled with the blaring music of the gambling houses. This universe has disappeared. It survives only on the main synagogues, now museums, which stand only steps away from the grand, straight avenues born of modern urban planning. In the past, these synagogues, with their mysterious, otherworldly facades, stood out among the sordid hovels that seemed ready to overwhelm them. Not long after the demolition of the ghetto, the poet Jaroslav Vrchlicky wrote, “You are like widows, gray synagogues/ Clothing torn and head covered with ashes/ But when night with her black tallit descends on earth/ I see your windows shine with candlelight and scarlet”. The ghetto was razed, but its memory lives on, as Franz Kafka recalled in his conversations with Gustav Janouch.

Impressions of the ghetto

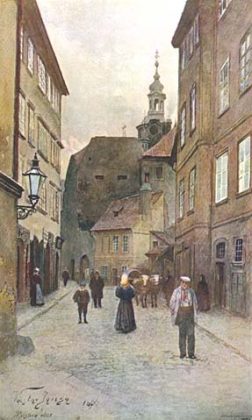

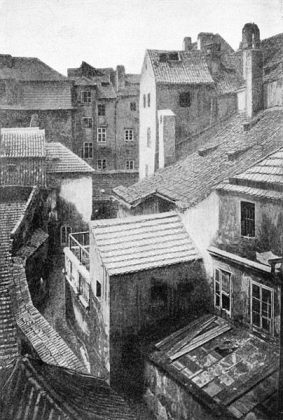

“The picturesque aspect of the Ghetto (as we see it in yellowed photos and in the paintings of Jan Minarík, Antonín Slavícek and other artists from the beginning of the twentieth century) was a result of its daredevil architecture, the dense interweaving and overlapping of misshapen, damp, run-down, tainted hovels, nests for the King of Mice and his subjects. It was a bizarre labyrinth of filthy, unpaved alleyways as narrow as mine shafts, where sunbeams rarely swept away the refuse of the shadow: ugly, fetid alleyways running through the belly of a dilapidated tenement only to end like bats on a blind wall; alleyways like crevices crisscrossed by patches of mould and foul smells; zigzag alleyways with streetlamps on the corner, cesspool-like puddles and arched wooden doors; alleyways, whose bends and curves lent them a certain drunken, wobbly, dreamlike quality.”

Angelo Maria Ripellino, Magic Prague, Trans. David Newton Marinelli, Ed. Michael Henry Heim (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).

“In us all it still lives -the dark corners, the secret alleys, shuttered windows, squalid courtyards, rowdy pubs, and sinister inns. We walk through the broad streets of the newly built town. But our steps and our glances and uncertain. Inside we tremble just as before in the ancient streets of our misery. Our heart knows nothing of the slum clearance which has been achieved. The unhealthy old Jewish town within us is far more real than the new hygienic town around us. With our eyes open we walk through a dream: ourselves only a ghosts of a vanished age.”

Gustav Janouch, Conversations with Kafka (London: Quartet Books, 1985).

The Jewish Museum

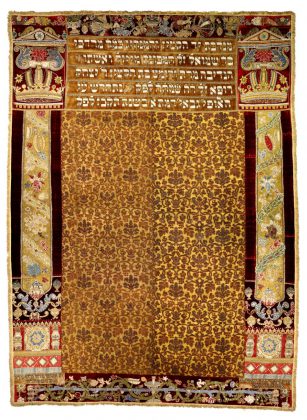

The Jewish Museum of Prague, created in 1906 as a symbol of Czech Jews’ assimilation, manages the synagogues and the old Jewish cemetery. It possesses some of the world’s richest collections of religious and domestic objects, manuscripts, paintings, and engraving gathered before the war, as well as numerous pieces that were pillaged by the Nazis in Bohemia and Moravia to be displayed in their “museum of the vanished race” that served their anti-Jewish propaganda machine in Prague. This stratagem ended up saving valuable objects and the several dozen intellectual employed to classify them. The idea for the museum had been nurtured by certain Jewish communities in the Czech lands that managed, with considerable difficulty, to convince the occupation authorities of the the worthiness of their plan. The majority of the employees of the Jewish Museum were finally deported in 1944, but the collections were saved. Under Communism it became the State Jewish Museum. The collections and so the heritage of the Jewish community of the Czech Republic were handed back in 1994. A selection of objects, the oldest ones, are displayed in the Meisel Synagogue and depict the history of the Jews in Bohemia-Moravia from their origins to the time of their emancipation. The rest of the exhibition, devoted to Jewish life from the eighteenth century until the end of the Second World War, occupies the rooms of the Spanish Synagogue, restored in 1998. The Pinkas Synagogue has a memorial bearing the names of the some 80000 Jews of Bohemia-Moravia who were victims of the Shoah.

The old Jewish quarter

A visit to the old Jewish quarter and its monument requires at least a full day, although the sites are all concentrated in a few streets between Pařížská and Kaprova avenues. Tickets valid for the entire tour can be bought at the entrance to the cemetery of the Jewish Museum. The synagogues and the cemetery are open every day except Saturday and Jewish holidays.

The jagged brickwork of the Staro-Nová Synagogue’s pediment looks as though it were pulled from an Expressionist film set. Now crowded on all sides by the surrounding buildings, this medieval synagogue set among the little streets of the ghetto has intrigued travelers and passerby for centuries with its narrow windows and strange facade. Today this synagogue is the oldest north of the Alps. Built in approximately 1280, it is even older than the Saint Guy cathedral of Prague. It was first called the “New”, and later on the “Old-New” Synagogue when other grand synagogues were erected in the quarter in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. None of the other synagogues, however, have so many legends attached to them. One legend claims the celebrated synagogue was built with stones of the Temple of Jerusalem brought by Jews from Palestine at the time of their exodus. Another version of this tale recounts that the stone blocks were transported to Prague by angels. Other legends assert that when work began on the foundation, the synagogue suddenly rose from the ground after only a spadeful of earth had been dug. Abundant local romantic literature asserts that the Golem’s remains were located for many years in the synagogue’s rafters under its great, steep roof.

Although it remains the most important and moving place of Jewish worship in Prague, the synagogue today is overrun with tourists. Located on the Červená ulička (Red Street), the street names recalls the numerous butcher chops that existed on the small square nearby before the destruction of the ghetto. The replastering and other restorations of the synagogue have erased the patina created by centuries of lamp-oil smoke. The mildew stains on the walls that some had seen as traces of blood from the thousands of victimes of the pogrom of 1389 have likewise vanished. The synagogue’s interior plan is oblong, a borrowing from medieval monastic architecture. Two octagonal pillars support Gothic arches and separate the space into two naves. The interior layout is similar to that of the synagogue of Worms (1175) in southern Germany, which was torched by the Nazis. For many years the nave was reserved for men; women followed the services from the hallway and through small windows. Standing between two columns, the fifteenth-century bimah is surrounded by a large Gothic grille and the wooden seats of the faithful. The first seat to the right of the pulpit, bearing the number 1 and crowned by a Star of David, once belonged to Rabbi Loew. The aron of the eastern wall features tow Renaissance columns. Finely carved stone floral motifs decorate the tabernacle. The prayer hall is illuminated by large wrought iron lamps. Carved grapes and vines adorn the magnificent tympanum of the great door to the prayer hall. These motifs are similar to those found in the famous Cistercian abbeys of southern Bohemia. Some historians believe that the same artisans worked on the structures of both faiths. The building’s heavy masonry has protected it from the many fires that have ravaged the ghetto over the centuries.

The Jewish city hall stands on Maislova Street, one of the ghetto’s principal arteries and at one time named the Zlatá ulička (Street of Gold). The building was constructed cira 1560 with funds given by Mordechai Maisel, the financier and philanthropist who was the quarter’s first mayor. Devastated by a fire 1754, the edifice was rebuilt according to the rococo-style plans of architect Josef Schlesinger. The city hall is crowned by a small tower with two clocks, one with Roman numerals and the other, beneath it, with Hebrew numbers and hands that revolve counterclockwise. This building is now the administrative center for the rabbinate and the institutions of the Jewish community. Decorated with stuccowork and Stars of David, the large “Hall of Advisers”, has been the home of a kosher restaurant, Shalom, since 1954. The restaurant is managed by the community and serves up generous portions.

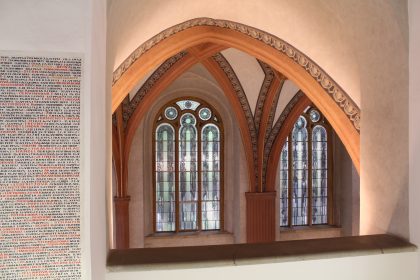

Across Cervená Street, one of the few remaining little streets of the ghetto, and opposite the Stare-Nová Synagogue is the Vysoká (High) Synagogue. It belong to the same ensemble of buildings as the Jewish city hall and was built during the same period, in 1568, by the same architect, Pankratius Roder, from South Tirol. Damaged by several fires, notably that of 1689, it was remodeled at the end of the seventeenth century. The large prayer hall on the second floor retains its original appearance, with graceful arches of a mixture of late-Gothic and Renaissance styles and three beautiful windows on the northern wall and two on the eastern wall. The magnificent Baroque aron is located between the two windows of the eastern wall and dates from 1691. The synagogue was active until World War II, and again between 1946 and 1950. It has since become an exhibition space for a collection of sacerdotal vestments belonging to the Jewish Museum.

The Maisel Synagogue was erected at the edge of the ghetto by Mordecai Maisel, who bought a piece of land there is 1590 for the construction of a private synagogue. An inscription, almost completely effaced, celebrates the many charitable deeds of the philanthropist. Constructed in 1591-92 after a design by Yehuda Goldschmied de Herz and Josef Wahl, Maisl’s synagogue was the most elegant and richly decorated synagogue in the ghetto. It was destroyed by a fire in 1689, and rebuilt on a more modest scale. Again in 1754 the synagogue was devastated by fire. It was reconstructed in 1864, and made over yet again, this time from 1893 to 1905 in a neo-Gothic style, when the entire zone was cleaned up. The synagogue was restored in 1994, and it has served as one of the main exhibition spaces of the Jewish Museum since the early 1960s. On display you can find the permanent exhibition “History of the Jews in the Bohemian Lands in the 10th-18th centuries”.

The Klausen Synagogue was built in 1694 right next to the entrance of the Jewish cemetery and on the former site of the Klausers. The Klausers were three small buildings, one of which was a synagogue erected in 1564, and another of which was Rabbi Loew’s school. All three were destroyed in a major fire of 1689. The current synagogue takes its name from the Klausers, whose place it occupies. It was the second most important house of worship in the Jewish community. The building has been renovated several times, notably in 1883 by the architect Bedrich Münzberger, who enlarged the original structure and added an original women’s gallery from 1694. The majestic prayer hall, which features an impressive aron dating from 1696, currently serves as a repository of a permanent exhibition dedicated to “The Jewish Customs ans Traditions”. On the western wall, there is a magnificent aron of carved wood originally from the synagogue of Podboransky Rohozec.

The Pinkas Synagogue was built on the edge of the old cemetery in the fifteenth century for the Horowitz family and later enlarged in the middle of the sixteenth century. Erected in 1530, it was enlarged in a late-Renaissance style in 1625. The current building preserves the original plan, but the large Gothic nave with its rich polychromatic decorations have totally disappeared in the numerous renovations, especially those from the beginning of the seventeenth century designed by the architect Yehuda Goldschmied de Herz. The synagogue was altered again more than a century later, in 1862. The aron is Renaissance-Baroque in style. The stone bimah is enclosed by a lovely metalwork grille dating from the eighteenth century. Off to the side you can see the main remnants of a mikvah. In 1960 the walls of the synagogue were inscribed with the names and birth and death dates of the 77297 Jews from Prague and the surrounding Czech lands killed by the Nazis. The synagogue was closed for about about thirty years and was restored only in the late 1990s.

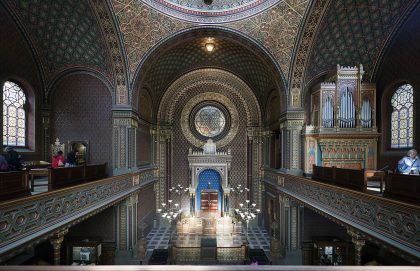

The Moorish-style Spanish Synagogue was built in 1868 and occupies the place where the oldest synagogue of Prague once stood. The Old School, as it was called, served the Byzantine community of Jews in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. They had their own small ghetto separated from the Jewish quarter and near the Church of the Holy Spirit and a convent. The synagogue was destroyed by pogroms, including that of 1389, and several fires and rebuilt, each time to its original plan of a long hall covered by a steep roof. It became the first Reform synagogue in the city at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and an organ was installed. In 1868, it was decided to raze the older and set in its place a larger place of worship symbolic of the new role the most modern fringe of the Jewish community began to have in Czech society. Architect Johann Bělský, who also built many new houses in the Jewish part of town, chose the Moorish style so fashionable among Jewish communities (especially those of Germany) at the time. Erected according to architect Bedrich Münzberger’s plans on a square plan with a large dome, the interior of this synagogue is richly decorated with stuccowork inspired by the Alhambra of Granada. The synagogue has been restored and serves today as an exhibition hall for the Jewish Museum.

The synagogues in other parts of Prague

Other small synagogues were constructed during the same period in a variety of districts in Prague. Most of them, including Kralovske Vinorady, were destroyed during the air raids of World War II. The others were deconsecrated and transformed into warehouses or stores. Nevertheless, one can still admire the very interesting oriental style functionist building built in 1930 for the neighborhood Jewish community on Strupewnického Street in Smíchov (in the southwest part of Prague). In Karlín (in the eastern part of Prague) a tiny neo-Renaissance synagogue was constructed in 1860 and then transformed into a Hussite church. It can still be found on a small street in the countryside cakked Vitkova Street.

Around the time of the great urban renewal projects of the former ghetto at the beginning of the tewentieth century, three small synagogues were destroyed: the New Synagogue (end of the sixteenth century); the Tzigane Synagogue (seventeenth century, modified in the eighteenth), where the young Franz Kafka had his Bar Mitzvah at the age of thirteen; and the Synagogue of the Great Court (1626). The Synagogue of the Jubilee replaced these three and was constructed outside the old Jewish quarter in the Nove Mesto (New City). Erected in 1905-06, it celebrated the integration of Jews into Prague society at the beginning of the century. Constructed according to plans by the architect Alois Richter, its melds the Moorish style with Art Nouveau elements, especially in its interior design.

Rabbi Loew

Astronomer and mathematician, Rabbi Loew was born around 1525 near Poznan (in present-day Poland). The most respected Jewish thinker of his time, Loew was a renowned interpreter of the Talmud and the Law. Though above all a scientist, in the popular imagination of the nineteenth century he became a great Kabbalist, even a Jewish Faust, who had created a Golem, an artificial man of clay who escaped from his creator.

He was invited to meet Rudolf II on 16 February 1592, and according to legend, made shadows of the great figures of Genesis and the Patriarchs appear on the walls of the room. It was also reported that he succeeded in avoiding death for several years by tearing from Death’s hands the list containing the names of those slated to die. Death did manage to catch up to him, hidden in a rose his granddaughter gave him to smell. He died in 1609.

Although the cemetery’s wellmarked hallways have been cordoned off to prevent to tens of thousands of tourists who file through it each year from walking on the graves, the old Jewish cemetery in Prague remains the most famous and interesting in Europe. It is best to visit it either very early or very late in the day, or outside the tourist season altogether, in order to capture the poignant nostalgia of the place. Some 12000 gravestones are piled one upon another -sometimes three or four deep or more. The grounds are a hodgepodge of crooked stones, like swaying drunkards, buried almost to their tops, covered in ivy, and swallowed up by the damp, black earth. A few trees, mostly alders and elms, manage to grow in this mass of stones, their inclining trunks recalling the gravestones worn by the weather and caresses of the faithful. You can still make out the inscriptions in remembrance of the dead, and often the bas-reliefs symbolizing a family name, occupation, or the virtues of the deceased. Hands in a gesture of blessing indicate the tomb of a Kohen (or Cohen, Kohn, Kahn, or Kagan), descendants of Aaron and the great priest of the Temple, the Kohanim. The pitcher or basin adorning many gravestones marks the final resting places of the Leviyim, or the Levites (descendants of Levi), the second group in line after the Kohanim to read from the Torah during celebrations at the synagogue. Other motifs, such as palm leaves, recall the verses from the Psalms, “The good man will flourish like a palm tree” (Psalm 92:13). A bunch of grapes symbolizes abundance and the kingdom of Israel. Despite the prohibition against representing the human figure, there are a few feminine silhouettes carved onto tombs dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, symbolizing, according to the tradition, the desire of God to enter the hearts of men. Other, more prosaic images represent an occupation, such as a boat for merchants, tweezers for doctors, or scissors for tailors. There are also many sculptures of animals, first and foremost the lion, representing the royal kingdom of Judah and the twelve tribes of Israel or recalling the name of the deceased (Löwe, German for “lion”, or Leyb in Yiddish). The bear also figures in this stone bestiary, suggesting the search for honey that symbolizes the Jew immersed in the sweetness of the Torah. Also depicted are the doe and the gazelle (“because God runs to the synagogue to hear the prayers of Israel”), as well as birds.

The oldest tomb is that of Rabbi Avigdor Kara, which dates to 1439. An older cemetery, desecrated at the time of the pogrom of 1389, was found near the present-day Vladislavova Street in the Nove Mesto. The last tombs were erected in 1787, the year the cemetery was closed at the command of Emperor Joseph II. Small stones are placed on the most celebrated tombs, such as the one decorated with lions of the wise and holy rabbi Yehuda Loew ben Betsalel (1512-1609), called Maharal and reputed to have performed miracles even after his death. Pilgrims slide slips of paper with their requests and prayers in the crevices of the red stone. Another venerated tomb is that of Mordecai Meisel (1528-1601), the philanthropic financier who was mayor and benefactor of Prague’s Jews. The epitaph on his tomb recalls that “his generosity was without limits and his charity was given with all his heart and soul”.

The Zizkov cemeteries

The earliest graves of the Old Zizkov cemetery date to 1680, but the cemetery really began to grow after 1787 with the closing of the one in the old ghetto. In the restored section one can see lovely Baroque and classical sepulchers. The last burials date from 1890. Part of the cemetery has been transformed into a park. There is also a television transmission tower on the grounds.

The new cemetery, established in 1890, is Prague’s only Jewish cemetery still in use. The large hall, which also houses the administrative offices, was constructed in a neo-Renaissance style at the end of the nineteenth century. The cemetery includes magnificent tombs in the Art Nouveau, neo-Gothic, and neo-Renaissance styles. Franz Kafka is enterred here beside his parents. The tomb is crowned by a sober gray stone stele where visitors often leave small stones in homage. Opposite is the grave of the writer Max Brod, Kafka’s friend and confidant, who, after Kafka’s death, refused to burn Kafka’s writings despite the demand in his will.

The Franz Kafka houses

A visit to the nostalgic sites of Jewish Prague would not be complete without a trip to the places where the most famous Jewish author lived. All his life, despite his parents’ many changes of residence and his own, Franz Kafka stayed within a narrow perimeter of the old city center around the large square, some three hundred feet from the former Jewish quarter.

Kafka’s birthplace (at 5 Radnice Street) is situated on the northeast side of the large square. He was born here 3 July 1883. Of the original building destroyed in a fire in 1896, only the main entrance remains. A bust commemorating the writer was placed there in 1965.

Two years after their son came into the world, Kafka’s parents moved. After some wandering around the quarter, they settled in the U Minuti House on the old city square, near the great clock. The facade of this seventeenth-century building is decorated with biblical scenes and classical legends from antiquity. Kafka lived here from age six to thirteen; his three sisters Elli, Valli, and Ottla, who died while being deported, were born here.

In 1896, the Kafka family moved into a lovely old home, “In the Name of the Three Magi”, at 3 Celetná Street. Kafka, whose bedroom faced the street, remained here until the time of his law studies. His father’s first store, Hermann, was a little further away at number 8 of the square on the north side, but it has not been preserved. A few years later, Kafka’s father moved his business to Celetná Street, and then, in 1912, to the ground level of the imposing Kinsky Palace on the square. The German lyceum that Kafka attended was located in a wing of this building.

In 1907, about the time Kafka had begun working at Assicurazioni Generali, the family settled at 36 Niklasstrasse (now Parizká Street) in a elegant building constructed on the ruins of the former ghetto. The house, zum Schiff (like a boat), was very close to the Vltava. Here he wrote three of his masterpieces, The Judgement, Amerika, and The Metamorphosis. The building was destroyed in 1945.

In 1913, the Kafka family returned to the old city square to live in the Oppelt House (Starometseke Námesti): Kafka’s bedroom faced Parizká Street.

In 1914, Kafka left for nearby 10 Bilkova, lent him by his sister Valli and where he began to write The Trial.

Beginning in May 1915, Kafka lived alone for the first time in the “House of the Golden Pike” (now 16 Dlouhá Street). “Without a broad view, without the possibility of seeing a big swath of the sky, or at least a tower in the distance to compensate me for the lack of open, empty countryside -without all that, I am an unhappy man, a man oppressed”, he wrote to Felice Bauer at the time.

He next lived for a few months on the other side of the river in a little house at 22 Zlata Street (Little Street of the Alchemists), near Prague Castle. In May 1917, he also rented an apartment in the magnificent Schönborn Palace (15 Trziste), today the location of the American embassy.

Jewish sites in Christian Prague

Some of Prague’s extraordinary architectural heritage is directly tied to the Jewish past.

On the Charles Bridge, the third statue on the right coming from the old city represents a Christ bearing a large golden inscription in Hebrew (“The Holy One, the Lord”) paid for as a fine in 1696 by a Jew accused of having blasphemed the name of Jesus.

In the Church of Saint Mary of the Tyn in the old city square, there is a plaque commemorating a “hero” of the Counter-Reformation. “Solemnly buried here is the fellow believer of the Catechism, Simon Abeles, killed in the name of hatred of the Christian faith by his own father, a Jew”, states the text, recalling the young Jewish boy, aged twelve, who, tempted to convert, was killed by his father and his father’s friend 21 February 1694. Arrested in the old city, Lazar Abeles, the father of the victim, hanged himself by his prayer shawl in his cell in the city hall. The corpse was dragged outside the city walls, drawn and quartered, mutilated, and his heart was placed on the mouth of his slain son. His accomplice, one Löbl Kurthandl, was tortured on the wheel until he renounced his faith, after which he was put to death. The remains of the child were found intact in the Jewish cemetery -a sign of a miracle- and were laid out for a month in the church of Tyn. During this time, the village and the clergy filed past past the body to pay their respects. In the years between the two world wars, several historians, including Egon Erwin Kisch, examined records of the trial and forever put to rest the legend forged by the Jesuits in the seventeenth century. The circumstances surrounding the death of the child remain unclear, but the charges were entirely fabricated in order to force the guilty to convert.