The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

This city of Transcarpathia, located at the crossroads of several nations with evolving borders has all the more been marked by many influences: Czech, Slovak, Polish, Austrian, Hungarian, Ukrainian …

The Jewish presence in Mukachevo, formerly known as Munkacs seems to date from the end of the 17th century. The first synagogue dates from 1768. Many religious currents were represented in the yeshivot, impregnated until the end of the 19th century by rabbis such Hayim Sofer and Shlomo Shapira. Furthermore helped by a recognition of rights by the local authorities and a good understanding between all populations.

Growth of Jewish culture

The Jewish community is very poor materially, most of the people being farmers or workers, but of remarkable intellectual wealth. Hasidism mingled with other Orthodox movements, but also Zionism and cultural Judaism. Three weekly newspapers in Yiddish were then published in Munkacs! The Yidishe shtime, the Yidishes folks-blat and the Yidishe tsaytung. And even a humorous newspaper, with the name slightly indicative of its function, Der Humorist.

Not only confined to studies, which proved an openness to the arts, an Orthodox Jew opened the city’s first cinema. Less entertaining but rather urgent, the city’s Jews repelled the assaults of Cossack troops in 1919.

During this period, the complex regional relations meant that the city was cut in two by the Czech and Romanian armies, requiring a passport to move from one side to the other. In 1920, the city became Czech, in accordance with the Treaty of Trianon, withdrawn from Hungary which ruled it until then. A little more than 5,000 Jews were counted in 1891, which constituted half of the total population. 10,000 Jews inhabited the city in 1920, in similar proportions.

A model progressive Jewish school

In 1925, the Hebrew Gymnasium of Munkacs was inaugurated. One of the most progressive Jewish high schools in Eastern Europe. Classical education was taught there, in Hebrew. Young women and men studied together and equally. An openness not always welcomed by some Orthodox representatives, threatening parents of students and teachers with excommunication. Tensions also existed between the various Orthodox movements.

Before World War II, Munkacs had the largest Jewish community in this region, with around 30 synagogues, mostly small shtiebels, and made up almost half of the population. The two main synagogues being the Bais Hakneses Hagadol and the Bais Medrash of the Munkacser Rebbes .

Destruction of the communities during the Holocaust

Taking advantage of the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, Hungary recaptured the city in 1939. Religious and cultural activity was drastically curtailed, and many Jews were sent to forced labor duties in the Hungarian army.

Following the German invasion on March 19, 1944, Jewish communities in and around the city were destroyed, with scores of Jews deported to Auschwitz. Among the 2,000 survivors (out of 15,000 Jews), Chaïm Kugel, the founder of the Hebrew Gymnasium of Munkacs. He immigrated to Israel and became the mayor of Holon.

Rebirth of Jewish life

Following the war, Munkacs integrated Ukraine and was renamed Mukachevo. In 1966, of the 50,500 registered inhabitants, 6% declared themselves Jewish. In 2001, of the 82,200 inhabitants, they represented only 1%. Some period buildings are still standing but hardly recognizable, transformed by the Soviet era and used for other functions.

The ancient Jewish cemetery had been almost completely destroyed. Around a hundred graves were reinstalled by the community in a cemetery in the neighboring village of Koropets. a new Jewish cemetery is also present in town.

Nevertheless, in recent years a Jewish cultural life has been reborn there. A synagogue was inaugurated in 2006. All this, in large part with the help of Americans, some of whom are descendants of Mukachevo. About a hundred Jews live there today.

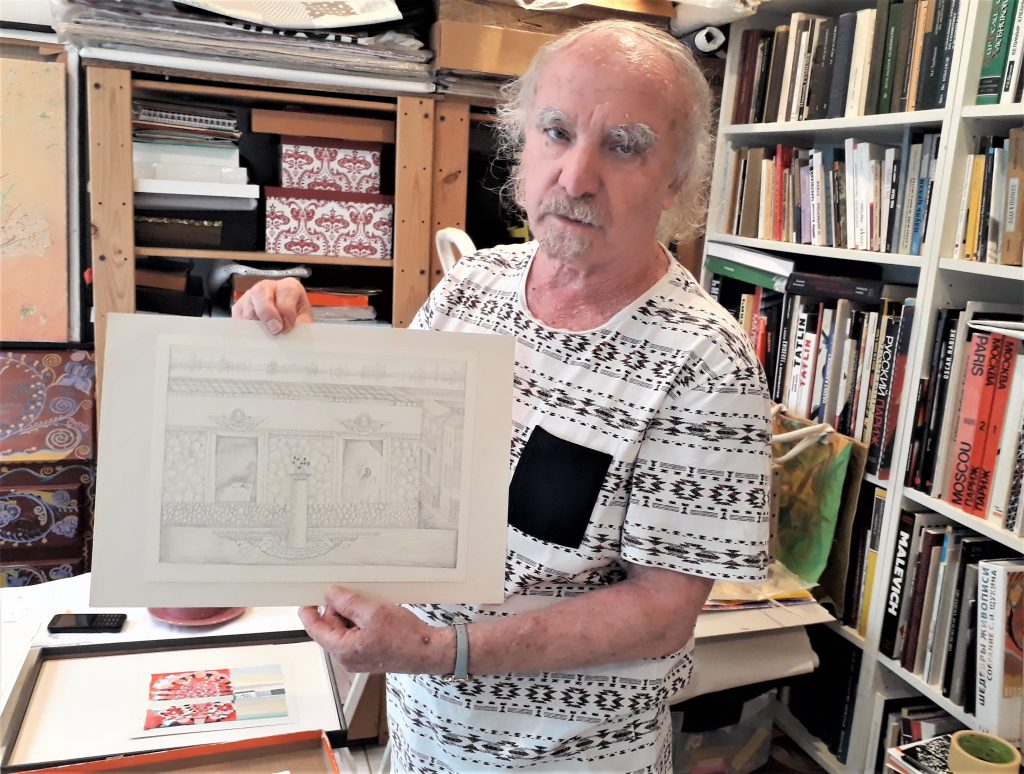

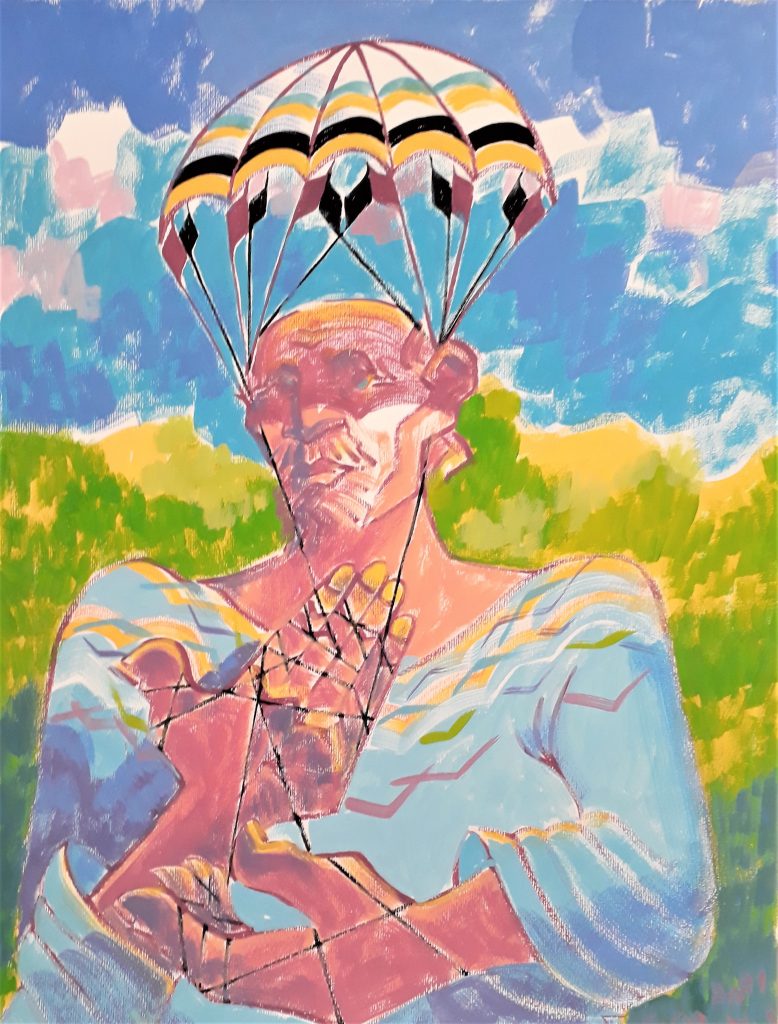

Interview of the great painter Samuel Ackerman

Born in 1951 in the Transcarpathian region, Samuel Ackerman grew up in Mukachevo and was educated at the Uzhhorod School of Art (formerly known as Ungvar when it was ruled by Hungary until the end of WWI). Places located at this cultural crossroads of languages and civilizations and at this natural crossroads made up of mountains, forests and lakes placed on top of each other like layers of paint on a canvas and where the discernment of the element which culminates can be proven difficult.

In the movie A Monkey in Winter, in his famous replica to Jean-Paul Belmondo, who enthusiastically speaks to him about the Prado, Jean Gabin prefers to see the garden that surrounds the building.

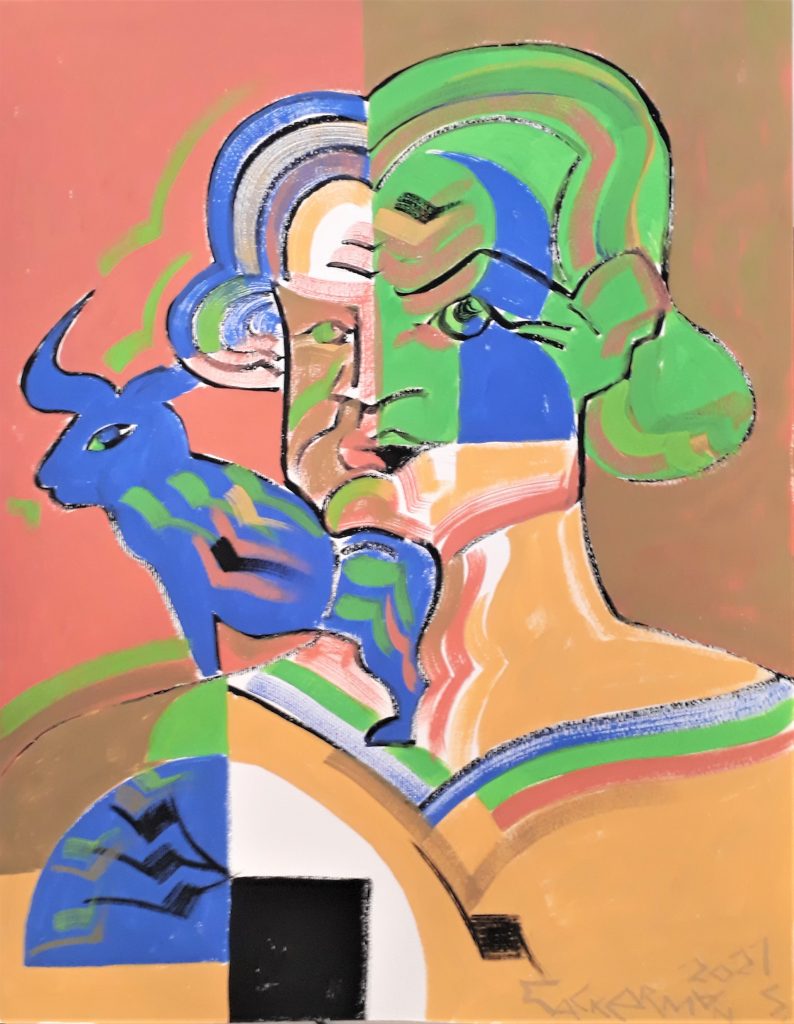

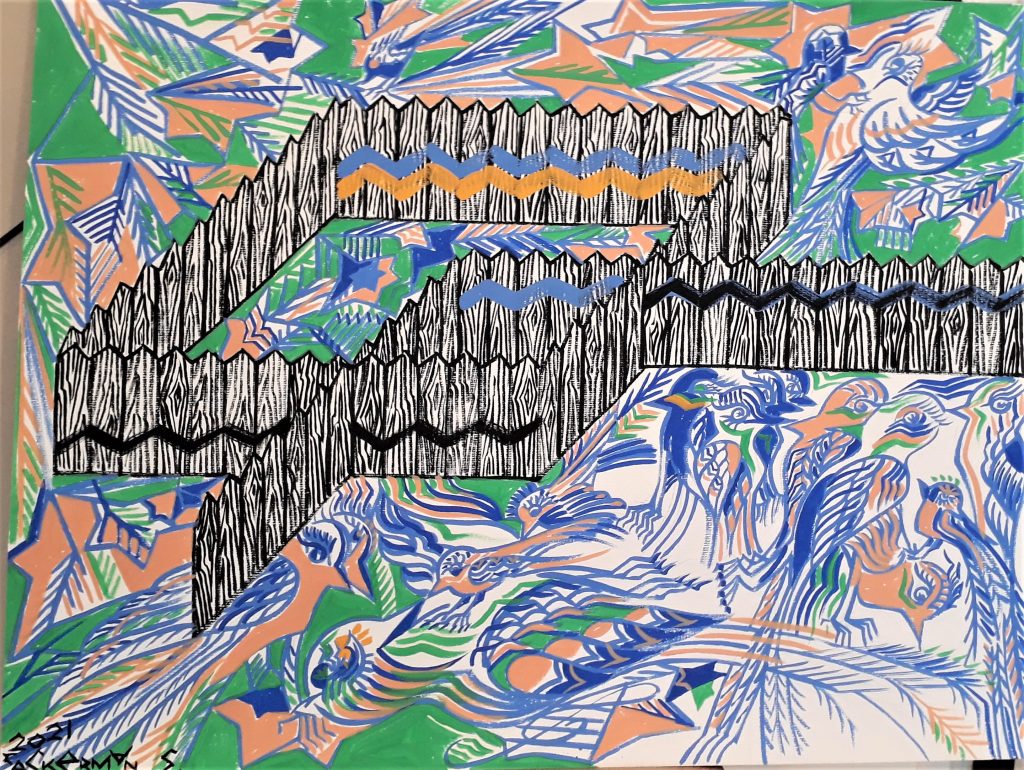

The Uzhhorod Art School and cultural and natural environments were never just surrounding each other. They influenced and responded to each other. And it is no coincidence that Samuel Ackerman, in the 1970s, became one of the most influential Israeli artists.Pursuing these dialectics between art and nature, between ancestral and contemporary culture, he unrolled his scrolls, let the imaginary creations of our inner genizah bloom in the deserts. The avant-garde Leviathan movement was born, along with Avraham Ofek and Mikhail Grobman.

In 1984, Samuel Ackerman moved with his family to Paris, where he became one of the figures of this bohemian artist from Eastern Europe, magnified from the cellars of the piano bar by Serge Gainsbourg to the ceilings by Marc Chagall.

Meeting with Samuel Ackerman to discuss the city of Mukachevo and its very special and inspiring Jewish life. The Minotaur Gallery has published a collection of much of his work.

Jguideeurope: Your family originates from the region?

Samuel Ackerman: In Transcarpathia, there were three big cities: Mukachevo, Uzhhorod and Berehove. A large proportion of the regional population was Jewish until World War II and the mass deportation of 1944. My father, Meïr Ackerman, is from Makarovo, a village between Mukachevo and Berehove. During the war, he was sent to a labor camp. My mother, Dora Gottesman, was from Krytoye, a village north of Mukachevo. At 22, she was deported to Auschwitz. Her astonishing strength allowed her to survive. Dora’s brother also returned from a labor camp, but the rest of the family were murdered in Auschwitz. My parents met in Mukachevo after the war. They first lived in Makarovo, where I was born, and then returned to Mukachevo. Although the Jewish population of this city was almost 50% before the war, there were very few families left after the war.

I was educated in Mukachevo, before pursuing artistic studies at the School of Fine Arts in Uzhhorod. It was attached to the Academy of Prague, which allowed us to be in contact with the works of the European avant-garde, beyond the East-West divide.

What motivated you to take this path?

A drawing teacher spotted my enthusiasm and potential, giving me great encouragement. He created a small museum within the school, mixing art with botany and zoology. He taught me techniques for gouache and watercolor. His teaching, as well as the opportunity to see him at work, gave me confidence. The first time I went out to study the natural elements, I took a box of gouaches given by my father. In this season, the cherry trees were dressed in white flowers. I wanted every flower to be present in my drawing. Faced with this difficulty, I folded my sheet in half and what was painted on one side was reproduced on the other. A funny experience, but it also made me realize that art requires patience above all else. My friend Alter Vogel did the same studies four years before me. He was the one who subsequently took the photos of my artistic performances with the meguiloth in the Israeli desert. About ten Jewish artists of this time followed the same training.

What remains of Mukachevo’s Jewish life?

The sovietization of the city was rapid after the war and the buildings and street names changed, especially with regard to Jewish cultural heritage. In downtown Uzhhorod, in a small passage, was the only active but hidden synagogue for major festivals. On Shabbatot and other holidays, prayers took place mainly in the apartment of a devotee. The apartment was in Berehove Street, the one that leads to this town. My parents and other locals were generally quite religious.

Fairly practicing, which did not prevent a great openness to the world in this crossroads of languages and civilizations. Like the Hebrew Gymnasium of Mukachevo.

Unfortunately this establishment was also requisitioned after the war and transformed into barracks for the Red Army. But the menorah which appeared on the metal fence was not removed because of the solidity of this construction. This high school, along with the red brick synagogue with oriental ornaments in Uzhhorod, was funded by Czech President Tomáš Masaryk.

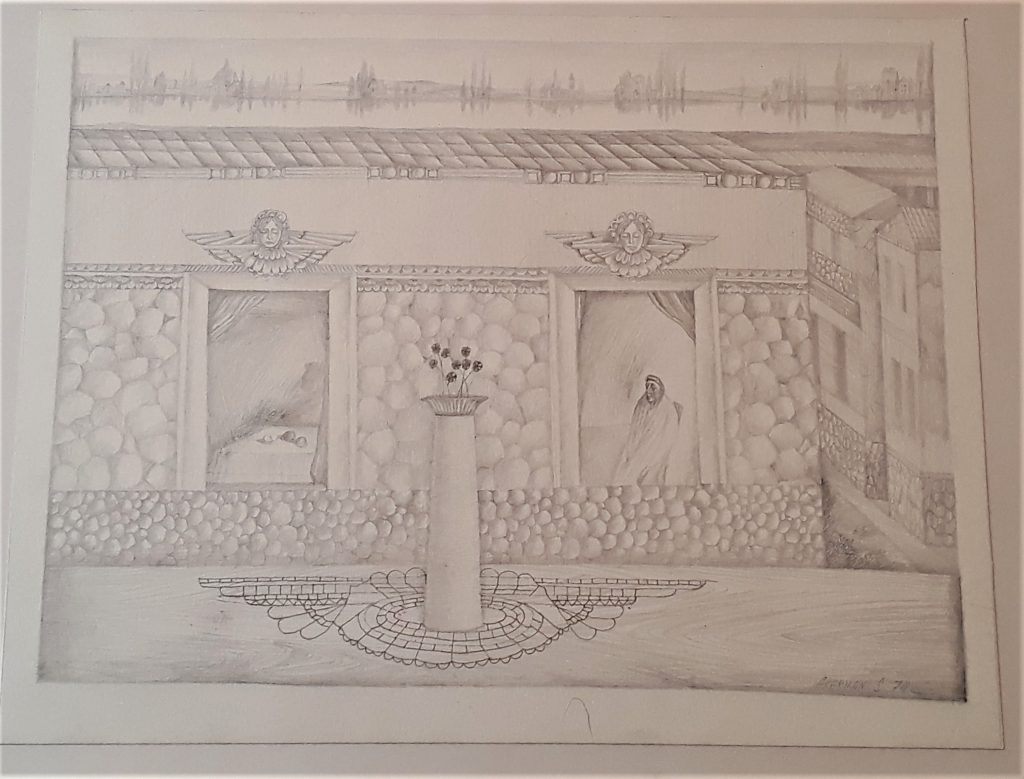

What elements of your life in Transcarpathia did you want to share in your first works?

First of all, the buildings. Similar to Brussels’ Baroque buildings with masks on the facades and other decorative elements inviting the viewer to a theater stage. I reproduced this in a drawing with a house with two windows and my father. The very pretty fortress near the city was also a source of inspiration, as were the rivers and mountains crossed by the villages of the region.

All the major cities of Transcarpathia had a fortress, built during the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In the summer, we often walked around barefoot. A direct contact with the land which I found very pleasant.

I was also marked by some amazing regional characters. Like the sculptor Turski of Mukachevo, who created the faces of wounded people in red earth, which adorned his garden. A very sensitive work that I have understood better over time.

Turski had studied in Leningrad but returned to Mukachevo before the end of his training due to health problems. In his luggage, the only book that his meager savings allowed him to buy: a collection featuring the works of Dali. Turski was the sole person in Transcarpathia to own this beautiful edition dedicated to the Spanish painter. In order to be able to consult it, those interested had to invite him to lunch. Then Turski would take them to his home to present and comment on the rare book. As a conclusion to this presentation, people were encouraged to invite him for an additional meal. But one day, falling in love with a woman, Turski entrusted the book to her to show to someone. She disappeared without leaving a trace. In the face of my friend’s distress, I coordinated an extensive regional research. This is how we found her trace in Berehove and recovered the book she used in the same way …

During your military service, you worked for the Armies Museum of the region.

Along four other people I have been tasked with renovating the museum. An interesting experience and one anecdote of which was a great source of inspiration for me concerning human comedy. A cake received by Marshal Grechko, commander of the Soviet Army who led the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, was kept there in a glass mausoleum. During the renovations, two Kazakh soldiers moved the mausoleum and it shattered, along with the cake it was supposed to protect. The officers feared that we would all be sent to jail! Especially since we were expecting a visit from a very high-ranking official two days later. I told the general that I was able to repair the damage. Not by reassembling the cake, which was obviously impossible, but by reproducing it in papier mâché. I worked for 24 straight hours, reproducing the cake in great detail with all kinds of collages and colors. By also permanently closing the glass packaging that protected it, so that the high-ranking officers would not notice the subterfuge. A parable of how art can repair. It was 1971, three years after the events in Prague, a very tense period. I was also part of a group of artists creating protest works inspired by Guernica.

You left the region for Israel where you created, along with other artists from Eastern Europe, the Leviathan movement. Was it right after your military service?

Not quite. I first worked a bit for the Mukachevo theater, participating in a show. Then, we obtained the authorization to go to Israel, following an initial refusal. We created Leviathan with Avraham Ofek, born in Bulgaria, and Mikhail Grobman, from Moscow. Grobman was a little older and already benefited from some notoriety in Moscow and Israel. This land was for me like a blank canvas, with its fantasies and new forms. A very exciting experience. With total freedom for committed artists, participating at this time in tense social debates. When I discovered the work of Emmanuel Levinas, I identified with his approach. His openness to other beliefs and literature, including the work of Dostoevsky, was decisive. He, along with others such as Martin Buber, brought about a great renewal of the Jewish perspective.

Another great intellectual of this time quoted in the beautiful book dedicated to you by the Minotaure gallery is Gershom Scholem. Have you met him?

Yes, in 1979. He attended a Leviathan exhibition in Jerusalem. He very much appreciated our approach. It exhibited works inspired by Andrei Rublev, painter of Orthodox mysticism. The light crosses Jerusalem and its buildings there, a meeting between two mysticisms. Confrontations between religious and cultural worlds often transcend primary perceptions, such as the important work done by the director of the Tel Aviv museum, Mordechai Omer, who was a very religious person. In the spirit of the prophet Isaiah who brings people together in peace through encounter and creation. Each migration enriches this land. In recent decades, great Ethiopian and North African artists have given their credentials to Israeli art.

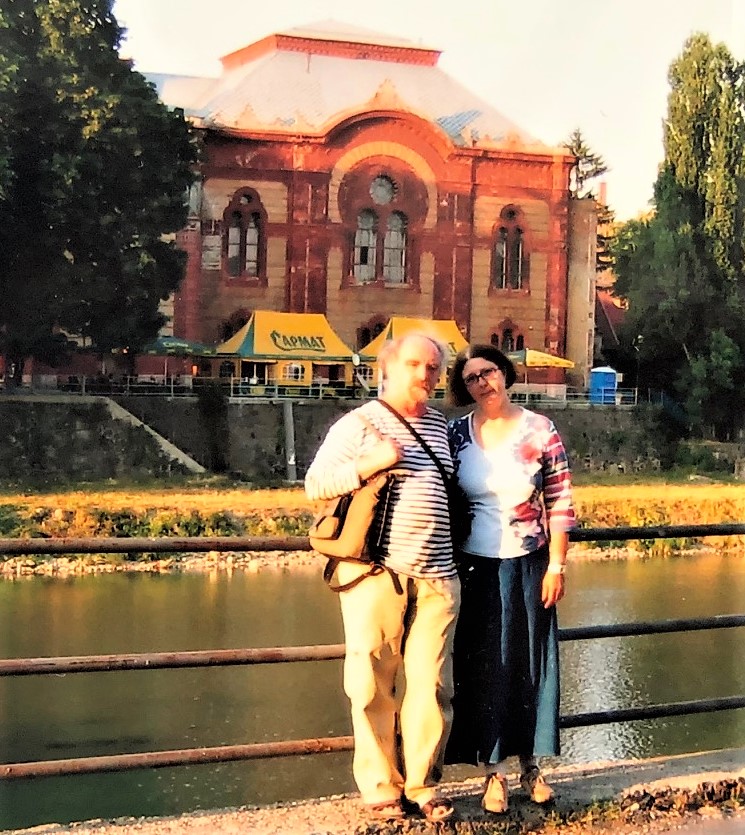

Have you been back to Mukachevo since?

Yes in 2007, with my wife Galia. But we had visited other cities in Ukraine before such as Lvov and Czernowitz. Then, the region of Transcarpathia, before continuing our trip to Poland. It was quite moving. But I never broke the link, keeping in touch with artists from Transcarpathia here in Paris, where I have lived with my family for almost forty years.