Below the bell tower of Prague’s Jewish city hall, there are two clock faces. One displays Roman numerals, and the other Hebrew letters. The hands of the first clock revolve in the normal clockwise direction while those of the second turn counterclockwise, following the customary manner of reading Hebrew right to left. Such clocks are rare, and this is the only one of its kind adorning a public building.

Apollinaire and Blaise Cendrars, like many poets and writers, were fascinated by the clocks, which evoked “a time that seems to forever turn backward”. Just opposite the tower one sees the large triangular, jagged facade of the Stare Nova (Old-New) Synagogue constructed in the thirteenth century. A few steps away is the entrance to the former cemetery and its 12,000 graves. Although no more than 1,200 jews remain in the Czech capital, before the war there were over 32,000.

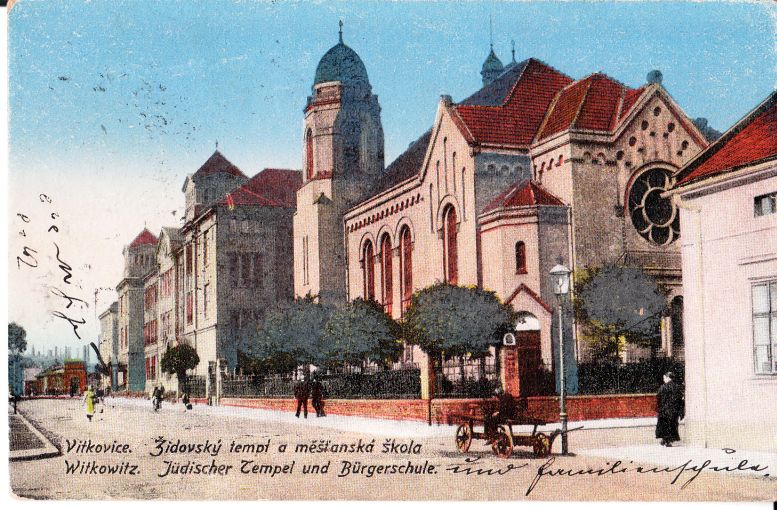

The 700 Jewish communities in the cities and villages of Bohemia and Moravia were almost completely annihilated by the Shoah. Synagogues and cemeteries outside Prague, where Nazi destruction was concentrated, largely escaped damage. With the extermination of the Jews, much of their heritage was pillaged, making these monuments, in the end, a “museum of vanished people”. The Czech Republic, with its remains of the Zidovske Mesto, the former Jewish quarter of the capital, and many small ghettos of the provinces, hold the richest and most compelling ensemble of Europe’s Jewish heritage.

The first records of a Jewish presence in the Czech lands date from the ninth and tenth centuries. The Jewish-Arab merchant and traveler Ibrahim ibn Jacob described Prague in 965 as a large commercial city: “The Russians and Slavs came there from their royal cities with their goods. Muslims, Jews, and Turks also arrived from the land of the Turks with goods and money”. As evident from this famous text, a number of Prague’s early Jews came from the east adding to those from German and Italian lands.

Early Jewish settlements concentrated on the left bank of the Vlata, at the foot of the hill where Prague’s castle would later be erected. Massacres and forced baptisms are mentioned as early as 1096, at the time of the first Crusade, but such tragedies remained isolated. A charter signed by Prince Sobeslav II in 1174 assured Jews the same rights and privileges as other foreign merchants. Jews also had the right to move freely about the city and settle along the large commercial routes. They were active in trade and the import of luxury goods from the Orient. Representatives of the flourishing community were given frequent audience at court. Around this time the Jewish community extended to the right bank of the river, establishing itself in an enclave north of the old city that would later become the Jewish quarter. Prague thus became one of the most important centers of Jewish culture in Europe. Such well-known Talmud scholars as Isaac ben Jacob and his disciple Abraham ben Azriel were members of this community.

As in the rest of Europe, the fortunes of Czech Jews changed after the Fourth Lateran Council (1215), which forbade them to possess land and drastically limited their economic activities. Jews were forced to live in separate areas and permitted only moneylending as a livelihood. Their lives improved, however, when King Premysl Otakar II, following the example of Pope Innocent IV in Rome, enacted in 1254 more favorable legislation that placed the Jews under the direct protection of the crown. It was during this period the New Synagogue was constructed, later called Stare-Nova (Old-New), the oldest building for worship in the Czech capital.

In the course of the following decades, despite Charles IV’s reaffirmation of these guarantees, the persecutions and massacres amplified. The most terrible was the Easter pogrom of 1389, which coincided with the two last days of Passover. Thousands of Jews were accused of having profaned the Host and were massacred by a fanatical crowd, encouraged by their priests. “Many were killed; to number them is an impossible task -young women, youths, old men, and babies. O you, God of all souls, not one of them needs you to recall him, you will judge all and you will know all…” So wrote Rabbi Avigdor, who, as a child, witnessed the carnage that claimed also his father. This elegy is read every Yom Kippur in the Stare-Nova Synagogue.

The Hussite wars that ravaged the Czech lands between 1417 and 1439 also adversely affected the lives of the Jews. The doctrine of Jan Hus made reference to early Christianity to demonstrate the abuses of the Church. “Catholics considered the Hussites to be a sect of Judaism, and the Hussites themselves , notably the most radical of them from Mount Tabor, saw themselves as an extension of biblical Israel”, notes historian Arno Parik, conservator of the Jewish Museum in Prague. He emphasizes that this anti-feudal revolt movement showed a certain indulgence to local Jews despite some exceptions.

The development of a monetary economy gradually marginalized the Jews. They were forced out of a number of towns in Bohemia and Moravia by a growing bourgeoisie desirous of eliminating Jewish competition in banking and lending. Although protected in the first decades of the sixteenth century by Kings Vladislav Jagiello, Ludwig Jagiello, and the Hapsburg emperor Ferdinand I at the beginning of his reign, Jews in the capital also suffered worsened conditions. In 1541, with the sovereign’s approval, the Diet voted to expel the city’s Jews. Only some fifteen families escaped banishment by bribing officials. Gradually, and for a large sum, Jews began returning to the city. In 1551, Ferdinand I forced the Jews of Bohemia to “wear a characteristic mark that would permit them to be distinguished from Christians” and to live within the wall of the ghettos.

In 1558, the Jews of the capital were again threatened with expulsion and had to pay in order to remain. This precarious situation lasted nine years, until Emperor Maximilian II issued a new decree authorizing the Jews already present in Prague and other Bohemian towns to stay where they were. The sovereign reinstated their freedom to engage in commerce and circulate freely. These measures were extended by the successor of Maximilian II, the flamboyant Rudolf II (1552-1612). This “wise fool and mad poet”, great protector of scholars, astrologists, and artists, settled in Prague with his entire court after six years on the throne.

During this period Prague’s Jewish community reached its height in the Baroque efflorescence of this heart of European intellectual life, as the great Slavic Italian writer Angelo Mario Ripelino masterfully described in his work Praga Magica (Paris: Plon, 1993). Leading Jewish personalities included, for example, the mathematician and astronomer David Glans and the scholar and chronicler Rabbi Yehuda ben Betsalel, who, according to later legend, created the golem, a manlike clay creature who escaped his creator. The legendary rabbi, whose tomb is still revered, even received an audience, on 16 February 1592, with Rudolf II, who was curious about kabbalistic rituals. Another great figure, the financier and philanthropist Mordecai Marcus ben Samuel Meiser, as mayor of the Jewish quarter enlarged the cemetery and had the Jewish city hall and new synagogues built. Jacob Bashevi, an adventurer and successful financier from Italy, was given the name von Treuenburg, and thus noble status, by his protector, the infamous condottiere Albrecht de Wallenstein. The Jewish banker believed himself justly rewarded for his loyalty to the emperor, a faithfulness shared by the majority of his community.

The splendor of Jewish Prague continued until the beginning of the seventeenth century under Ferdinand II, when the revolt of the Czech lands converted by the Reformation was crushed in 1620 in the Battle of White Mountain. The Counter-Reformation triumphed throughout the Hapsburg Empire. Prague’s Jews survived the attempts to expel them that affected the communities in the provinces, but a plague epidemic in 1680 and great fire in 1689 devastated the ghetto. Some Jews considered moving to another district, but finally the new ghetto was reconstructed on the ruins of the old.The situation nonetheless remained precarious, with explosions of anti-Semitism in 1694resulting from the Simon Abeles affair (a twelve-year-old boy who wanted to convert to Catholicism was killed by his father and one of his father’s friends).

At the beginning of the eighteenth century, approximately 12,000 Jews resided in Prague, making it the site of the largest Jewish settlement in Christendom. Life for the Jews became very difficult, however, under Emperor Charles VI (1711-40), who decided to drastically limit their numbers in the city. In 1726 he organized a census and enacted legislation putting a ceiling on the number of Jewish families living in Czech lands (8541 in Bohemia and 5160 in Moravia). Only one son per family -usually the eldest- had the right to marry and set up a household; other male children wanting to marry had to emigrate or wait for the departure of death of other family members. The ascension of Maria Theresa (1740-80) to the throne aggravated the status of Czech Jews, especially those in Prague.

To punish their alleged disloyalty during the Silesian War against the Prussians, the bigoted archduchess issued a decree in 1744 banning all Jews from the capital. The measure elicited far-reaching public outcry in Europe, but Maria Theresa remained inflexible, and 13,000 Jews left the city for the surrounding areas in March the following years. The archduchess then demanded they leave the Czech territories altogether. She finally relented, however, and after exacting exorbitant payments as restitution -equivalent to ten times the normal yearly taxes- the Jews were allowed to return to Prague in 1748-49. They lived under the threat of new expulsions in a dirty, overpopulated ghetto that contained on average 738 inhabitants per acre- a population density three times that of the rest of the city. Fires were unavoidable, and one in 1754 destroyed a large part of the quarter, including six synagogues. Only at the end of the century, with the ascension of Emperor Joseph II (1780-90), did the Jews see their fortunes improve.

The old Jewish quarter in Prague is still called Josefov, in honor of the enlightened sovereign who, with the Toleranzpatent (Tolerance edict) of 1782 abolished some of the discriminatory measures against Jews. This decree accorded Jews and Protestants a measure of religious freedom as well as most of the rights enjoyed by other citizens of the empire. Only sixty years later, however, did full equality become a reality. The modernizing reforms of Joseph II, which instituted, among other things, military service and German and the language of instruction, profoundly impacted not only the empire but also the daily lives of its Jews.

Thereafter, Jews had access to secondary and even higher education, but the communities of Bohemia and Moravia nevertheless had to create primary schools whose language of instruction was German. Traditionalists such as the extreme critic of the Haskalah Rabbi Ezekiel Landau denounced the assimilatory trends of by the Jewish Enlightenment then spreading among German communities. The Jews were forced to give in, however, and the first German-language Jewish school opened in Prague on 2 May 1782. An elite, modern Jew was thus born and nurtured, and drawn to leave the ghetto, whose walls did not officially come down until the middle of the nineteenth century.

Virulent anti-Semitism remained in the general population, as demonstrated by riots in 1844, when angry textile workers destroyed Jewish-owned factories. In 1848, as the great wave of revolution swept across Europe and the Czech lands, the army had to intervene in Prague to protect Jewish property. With the establishment of the first Austrian constitution in the same year, the discriminatory laws were abolished and the empire’s Jews finally won full and equal citizenship. It was another ten years, however, before they gained the right to own property outside the old ghettos.

The Jewish population grew considerably from the middle of the nineteenth century. By 1890, 94,599 Jews were living in Bohemia and 45,324 in Moravia. An even greater number of Jews streamed into Prague and other industrial centers from the outlying towns and villages. A Jewish bourgeoisie formed, but integration proved difficult. This was due as much to the Jews feeling obliged to chose between their own culture and the Germanic world surrounding them as it was to the Czech nationalism that was increasingly suspicious of German culture and openly anti-imperialistic. “For the young Czech nationalists, the Jews were Germans. For the Germans, the Jews were Jews”, emphasized Ernst Pawel in his biography of Kafka, who experienced this conflict directly The Nightmare of Reason: A Life of Franz Kafka (New York: Farrar, Straus, Giroux, 1984).

Hatred of Jews represented the only point of agreement between the most radical of the German and Czech nationalists. It is therefore not surprising that a number of the first militant Zionists came from Czech lands. On the occasion of the first language census of 1880, which could be considered as a veritable declaration of faith for one or the other of these two identities, only a third of the Czech Jews declared Czech as their principal language. Ten years later, 55% chose Czech, although in fact almost all Jews spoke German. Although under some pressure to do so, choosing the Czech language showed Jews to have an attachment to the burgeoning Czech nation.

The Czech nationalist youth movement slid easily into anti-Semitism: during the riots of 1897, after overrunning the most well-known German cultural and commercial establishments, for three days the crowd attacked Jewish shops and synagogues and anyone who appeared to be a Jew. This rage took and even more malicious form in 1899 with the Hilsner Affair, eastern Europe’s equivalent of the Dreyfus Affair in France. As Pawel notes, “Such was the hate-filled atmosphere of Kafka’s world. But he never had known anything else, and it took some time before he understood why it was so difficult for him to breathe”.

The Hilsner Affair

A young woman was found murdered on 1 April 1899, the night before Easter, near the hamlet of Polná, where she lived. For the villagers, it was clearly a Jewish ritual murder. A small anti-Semitic newspaper in Prague took the news item and amplified it into a public campaign accusing Leopold Hilsner, a Jewish cobbler in the village, of the crime. He was arrested, tried, and condemned to death without proof, thus unleashing a wave of anti-Semitism throughout the empire.

Tomás Masaryk, the future first president of Czechoslovakia, was the only politician to have the courage to go against the tide of public opinion: in a small pamphlet, he demonstrated in minute detail all the inconsistencies of the investigation. Student demonstrations succeeded in forcing him from the university. The booklet was banned, and he was labeled a traitor. Nevertheless, the Left was roused, as well as some of the intelligentsia. A new trial took place, with, however, the same verdict, but the death penalty was commuted. The cobbler was finally pardoned in 1918.

Around this time the destruction of the old Jewish ghetto began as part of a vast project to clean up the oldest neighborhoods of the city. The new Jewish elite, like that in many other European cities, had little interest in preserving the houses and sordid little streets that only reminded them of the horrors of the recent past. The urban renewal operation, which lasted until 1905, wiped away not only the run-down hovels and old buildings, but also small synagogues.

Prague’s German-speaking Jewish intelligentsia occupied a highly visible place in Czechoslovakia around the time of the First World War, especially on the world of literature as exemplified by Franz Kafka, Max Brod, Franz Werfel, Leo Perutz, and other members of the “Prague Circle”. In this city the poet Paul Kornfeld called “an asylum for the metaphysically alienated”, three cultures, German, Jewish, and Czech, intermingled, making Prague one of the great cultural capitals of Europe. Jews had key roles not only on the art and industry but also in the political life of the new country. A representative example is Adolf Stransky, publisher since 1893 of the prestigious Czech daily Lidové Noviny. President Tomás Masaryk even traveled to Palestine in 1927 in order to visit Jerusalem and the Jewish colonies. Unfortunately, the democratic and humanist Czech Republic that he succeeded in creating would last only twenty years.

In September 1938 Hitler imposed the Munich Accords on a Czechoslovakia abandoned by London and Paris. The accords amputated from Czechoslovakia the western Sudetenland, forcing thousands of Jews and Czechs to flee. Soon after, part of southern Slovakia was ceded to pro-Nazi Hungary, and German troops installed themselves in the rest of Slovakia, which in turn proclaimed itself an independent state allied with the Reich. In March 1939, what was left of Bohemia-Moravia was occupied by the Nazi army and placed under the direct control of the Reich. At the time, some 118,000 Jews lived in this territory. With the immediate imposition of the Nazi race laws, Jews were banned from all public positions and Jewish doctors were forced to limit their practice to Jewish patients. Jewish businesses were confiscated, Jews had to register all their belongings, and their capital and assets were seized. In 1940 they were forced to begin wearing the yellow star.

The Final Solution began in the Czech lands in October 1941 with the first convoy of 1,000 people to a Polish ghetto. A few months later, a ghetto was created in the small town of Terezín (in northern Bohemia), which had been emptied of all its inhabitants. Czech Jews were held there for weeks or months before transport to extermination camps in Poland. In all, approximately 89,000 Jews from Bohemia and Moravia were deported, of which 80,000 perished. After the war Jewish refugees from the east, especially Ruthenia, streamed into Prague. Approximately 19,000 Jews emigrated to Israel. Another wave of 15,000 departures followed in 1968 with the crushing of the Prague Spring by Soviet tanks. Today no more than some 6000 Jews remain in the Czech Republic.

Leave?

“I’ve been spending every afternoon outside on the streets, wallowing in anti-Semitic hate. The other day I heard someone call the Jews a ‘mangy race’. Isn’t it natural to leave a place where one is so hated? (Zionism or national feeling isn’t needed for this at all.) The heroism of staying on is nonetheless merely the heroism of cockroaches, which cannot be exterminated, even from the bathrooms.

I just looked out the window: mounted police, gendarmes with fixed bayonets, a screaming mob dispersing, and up here in the window the unsavory shame of living under constant protection.”

Franz Kafka, Letters to Milena, Trans. Philip Boehm (New York: Schoken Books, 1990).

Although Prague’s rich jewish heritage eclipses that of the country as a whole, Jewish institutions and tourists unduly overlook the outlying areas. In the small towns of Bohemia-Moravia, it is still possible to see extraordinary Jewish cemeteries, like that of Kolín, and well-preserved ghettos, as in Trebíc. The Nazis almost completely eliminated the small Jewish communities of the Czech territories, and a half century of neglect under Communism destroyed much of what remained of this heritage. Many synagogues have been transformed into shops, warehouses, or municipal buildings, and new structures have been placed atop former cemeteries. Still, numerous traces remain of the some 118000 Jews who, until 1939, lived in Bohemia-Moravia, evidence discovered and catalogued through the patient work of historians and conservators.

Jiri Fiedler: Archaeologist of memory

Born in Olomouc in Moravia, the historian Jiri Fiedler worked almost completely alone for many years despite the indifference or even hostility on the part of Communist authorities, compiling a list of the last vestiges of some 700 Jewish communities -proof of their presence in Czech lands over many centuries. “Today there are 200 synagogues in this country. There were 300 more than that after the war”, states Fiedler. His book Jewish Sights of Bohemia and Moravia (Prague: Sefer Ed., 1991) is an indispensable guide and exhaustive catalogue of a constantly threatened heritage. Over the years dozens of small villages synagogues have been transformed into shops or storage place. Those in use as warehouses have been destroyed either by state or their owners. The small Jewish cemeteries dotting the Czech countryside are attacked by vandals convinced there is gold to be found in the Jewish tombs.