Below the Acropolis is Athens, a marble plaque engraved with a menorah has been uncovered amid the clutter of the Agora, near a statue of Emperor Hadrien. Perhaps it used to rest on one of the ancient synagogues visited by Saint Paul, who had as little success with the Athenian Jews as the Greek philosophers had with the Areopagus.

How far back does the Jewish presence in Greece date? This question remains unanswered to this day. An even earlier question is, When did the Greek themselves come in contact with the Jewish people for the very first time? Legend has it that the first meeting between the two communities was peaceful and courteous. Alexander the Great, on his way to conquer Persia, is supposed to have bowed down before the high priest in Jaddua in Jerusalem.

That Jews and Greeks rubbed shoulders before the Macedonian conquest is certain, including as mercenaries in the Egyptian armies. The Hellenization of Judaea following Alexander’s victory, however, was a source of extreme tension. A nationalistic and religious revolt was unleashed after a statue of Zeus was brought into the Temple of Jerusalem. For the Jews, such a sacrilege was, as the Bible describes it, the “abomination of desolation”.

Yet the unstoppable spread of Greek culture, along with the “scattering” of the Jewish people long before the Temple’s destruction by Titus in 70 C.E., quickly led to the translation of the Torah into Greek. This was the book of the Septuagint, translated by seventy-two scribes in Alexandria, Egypt’s great hellenistic port where Jews numbered one million, or a third of the city’s population. The book became, in the second century, the “official version” of that sacred text, the only intelligible one for Hellenized Jews and the sole means by which the earliest Christians received the Old Testament. Domination and coexistence, cultural and intellectual exchange and schisms (such as the one between the major Jewish philosophers Maimonides and Philo) thus wove the singular relationship between the two peoples.

Jewish communities first settled in present-day Greece most certainly around the third century B.C.E. However, according to Joseph Nehama in his monumental Histoire des Israélites de Salonique (History of the Jews of Thessaloniki), “more than immigration and the buying back of captives, it was the extreme force of proselytization animating the Jewish religion at the time that assured the recruitment and vitality of the colonies of the Diaspora”. It would be among such converts, the “Godfearers”, that Christian preaching would encounter its earliest successes.

Though most often city dwellers, Jews also lived in the countryside. In the Kalamariá region of Macedonia, a tombstone reveals that Abraham and Theodote, a Jewish couple, worked the fields there around the year 200.

Beginning with Constantin’s 312 C.E. conversion to Christianity, Roman emperors were from then on Christian, and the status of Jews within the realm began to erode. After the empire was split, moreover, the Jews abandoned the nation’s Byzantine section; accusations of being christoktonoi or theoktonoi (“murderers of Christ” or “murderers of God”) abound in religious literature of the era. Judaism was defined as the “death-bringing religion”, and Jewish proselytizing and mixed marriages were fiercely prohibited under Theodosian Code. Justinian’s Corpus Juris Civilis further reinforced in the sixth century restrictive laws against Jews. While synagogues remained protected religious sites, building new ones was strictly forbidden.

Life for the Greek-speaking, or “Romaniote”, Jews during the Middle Ages is not so well-known. It is certain that they endured invasions by the Slavs, Bulgars, and Normans both before and after the year 1000. Merchant and traveler Benjamin de Tudela, a Jew from Navarre, visited the Medieval diasporas in the twelfth century. In his Massaoth Schel (Itinerary), he mentioned the major Greek cities inhabited by Jews, including Corinth, Thebes, Návpaktos, Patras, Kastoria, and Thessaloniki in particular, where they numbered half a million and held a quasi-monopoly over the dye and silkworm industries.

After the fall of Constantinople in 1453, a nearly uninterrupted inflow of Jews found refuge in the Ottoman’s Empire new possessions. After the edict signed by Ferdinand and Isabella on 31 March 1492 expelling all Jews from Spain, they were welcomed these en masse. At the east-west crossroads, “Byzantine-Thessaloniki” became “Jewish Thessaloniki”. The first group supposedly arrived from Majorca: they were called Baal Teshuva, signifying the return to Judaism of the Marranos, Jews who, on the surface, converted to Catholicism to escape the Inquisition. A the years passed, Castilians flooded in an imposed their linguistic dominance; they were followed by Aragonians, Catalonians, and Navarrans, and later by the Portuguese, Apulians, Venetians, Moroccans, and Livornians. They gathered together by synagogue: kal Castilia, kal Aragon, kal Mayor, or simply Gueroush-Sepharad (Expulsion from Spain).

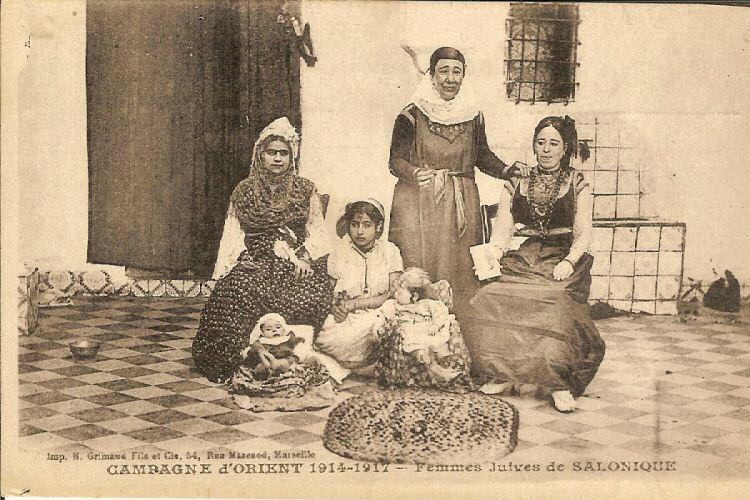

Censuses show that the Ottoman metropolis of Thessaloniki contained only around 2,200 Islamic and Christians households in 1,478; in 1519, less than twenty years after the Alhambra Decree, the city possessed 4,000 households, 56% of which were Jewish. A century later, there were 7,500 households here, the Jewish proportion reaching 68%. Thessaloniki, whose Jewish residents spoke a hybrid of Castilian and Hebrew called Judezmo, was called “Mother in Israel” and the “Jerusalem of the Balkans” for more than four centuries. The responsa, opinions by Jewish jurists in Thessaloniki on liturgical or practical questions, have become famous. Samuel Moise of Medina de Campo, who ordered the city’s various congregations to adopt uniform Sephardic rituals, delivered around 1,000 such opinions.

Spanish exiles settling in Thessaloniki shook up Romaniote Jewish communities and their traditions, as they did as well in Serres, Kavála, Patras, Drama, Larissa, Tríkala, and Rhodes. This was not the case in Ioannina, however. In the seventeenth century, the major centers of Jewish life were drawn into a religious storm by a false Messiah named Sabbataï Zevi. The crisis subsided with Zevi’s conversion to Islam, as rabbis smothered the faithful in suffocating rituals. Two centuries later, the fall of the Ottoman Empire plunged the Jewish communities of the Balkans, who had until then enjoyed official tolerance, into disarray and uncertainty.

One episode, or rather a legend with dramatic consequences, illustrates the difficult situation endured by the Jews during Greece’s long war for independence. This war began with a revolt, in 1821, throughout the southern part of the country. In retaliation, the Greek ecumenical patriarch of Constantinople, Gregory V, was hanged from the gate of the Phanar. Greeks claimed that his body had been thrown into the Bosphorus by three Jews on the order of the grand vizier. In any case, this was the excuse used by Greek insurgents for massacring thousands of Jews during the capture of the large city of Tripolis, in central Peloponnese. A flare-up of anti-Semitism punctuated every major liberation of “Greek lands” over th years to follow: Ioannina (1872), Corfu (1891), Larissa (1898), Tríkala (1898), Crete (1898), and Thessaloniki (1912 and 1931). Accusations of ritualistic crimes -the murder of Christians children by Jews- degenerated into pogroms. These events provoked the massive emigration of Jews to Marseille at the turn of the twentieth century, including the family of famous novelist Albert Cohen.

A reading of reports on this subject published by the Universal Israelite Alliance in the late nineteenth century is edifying. It is clear that such scheming was the work of a small minority in Greece, driven to extremes by a nationalist press and fringe of the lower Orthodox clergy. In contrast to these outbursts of anti-Semitism, which remained strong in Greece, liberal measures were also taken, beginning in 1832, by the Greek state in favor of equality of civil rights and religious tolerance.

With Thessaloniki integration within Greece’s borders after the Balkan war in 1912, Greek-Jewish relations grew tenser. Greek soldiers had taken de facto the largest port in the Balkans and a cosmopolitan city with a Jewish majority. Coveted by the Serbs, Bulgarians, and, of course, the Greeks, Thessaloniki was once a political center under the Ottoman Empire. David ben Gurion, the founding father of Israel, came to study Turkish here in 1910 to plead the Zionist case before the Sublime Porte. The Young Turk Revolution broke out, pushing the last of the Sultans, Abdul Hamid, into the background. Their right to Thessaloniki having been solidified after the First World War, the Greeks made it their objective to assimilate into the nation-state an especially stubborn Jewish population. Hellenization progressed bit by bit, accelerated by the great fire of 1917 that reduced to ashes the historic Jewish city along with its thirty-two synagogues. Well versed in the French language and culture thanks to efforts by the Universal Israelite Alliance, a large number of Jewish families emigrated -to Paris, in particular.

The demographic balance was permanently upset by an influx of 150,000 Greeks from Asia Minor as part of the dramatic population transfer required by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. “Furthermore, after the massive refugee influx, tensions mounted between Greeks and Jews in the city and in Northern Greece generally, as a result of exacerbated competition for the control of local economic life”, historian George Mavrogordatos stressed in Stillborn Republic. A pogrom erupted in 1931 in the popular Campbell suburb, followed by other fits of violence. Dockworkers from the port of Thessaloniki left en masse for Haifa. Ironically, calm returned only after the establishment of General Jean Metaxas’s Fascist regime in 1936, which publicly manifested kindness toward the Jewish community.

Such appeasement was to be short-lived. Describing the disappearance of entire community, their uprooting by the Nazis from soil they had inhabited for centuries, the most ancient for 2000 years, has never been properly accomplished -and cannot been done here. Before the despair that still grips the rare survivors and their descendants, the numbers poorly reflect the immensity of the drama that struck Greece’s 80,000 Jews, 80% of whom were victims of the Shoah. Of Thessaloniki’s 60,000 Jews, no more than 1950 remained by the end of the war.

Beginning in 1941, the Germans began taking anti-Jewish steps in Greece. In 1942, the great Jewish necropolis, the oldest and largest of all the Sephardic east, was razed through the active participation of the local authorities and part of the population. Under the iron rule of Eichmann lieutenant Dieter Wisliceny’s SS and Alois Brunner, himself in exile in Damascus, the Final Solution was set in motion in 1943. After their temporary confinement within ghettos, the Jews of Thessaloniki were deported in sixteen convoys to Auschwitz-Birkenau. The Italians and, to a lesser degree, the Spanish made heroic efforts to save Jewish life.

Beyond Thessaloniki, where indifference or hostility were manifest, Jews found courageous allies in a large part of the population, among the Resistance and even the authorities. The Orthodox archbishop of Athens, Monsignor Damaskinos, constantly intervened on their behalf and took the initiative of transmitting to the Germans letters of protest signed by around thirty celebrities and community leaders. In Thessaly and “Old Greece”, including Athens, hundreds of Jews were saved. The Athenian Parliament passed no anti-Semitic laws during the war, while the capital’s chief of police, Angelos Evert, provided Jews false papers.

Yitzhak Persky, British army volunteer and father of Shimon Peres, parachuted into the mountains of Attica in 1942. Captured by the Germans, he managed to escape, finding shelter for months in a monastery in Hassia. The 300 Jews of Zákinthos were all protected by the mayor and the archbishop, but the other communities in Epirus and the islands could not escape destruction. Of Corfu’s 2,000 Jews, only 120 avoided the death camps. In Thrace, 2,700 of the region 2,800 Jews were handed over to the Germans by the Bulgarian occupiers.

A half century has passed since the Shoah. The majority of those who survived have emigrated to Israel of the United States. Those who remained have settled mainly in Athens. Of the 5,000 Jews in Greece today, 4,000 inhabit the capital, while 1,000 are divided between Thessaloniki and a handful of smaller towns. An official monument in memory of the victims of the Shoah was unveiled in Thessaloniki a few years ago.

Interview with Zanet Battinou, Director of the Jewish Museum of Greece, about the Hannah project, fighting anti-Semitism through education and knowledge.

Jguideeurope: Can you presnt us the Hannah project?

Zanet Battinou: We recently organized a national conference – in the framework of the “CHallenging And DebuNkiNg Antisemitic MytHs HANNAH project, which focuses on Jewish history, culture, and life, the phenomenon of antisemitism and different approaches on combatting it in five European cities: Athens, Dresden, Hamburg, Krakow and Novi Sad.

Are there educational projects proposed by the JMG and how is the city of Athens participating in the sharing of Jewish culture?

The city of Athens usually organizes events in October – when the city was liberated, and they include some exhibitions or lectures based on Jewish testimonies. Furthermore, on the 27th January, the International Holocaust Remembrance Day, many commemorational events take place. This year, the building of the Parliament presented a relevant lit slide commemorating the Holocaust on its façade for the first time.

Which aspects of Greece’s Jewish culture are the summer tourists mostly interested about?

Basically, we’ve noticed that they are interested in visiting all the Jewish sites in the areas they visit – in Athens the JMG is one of their main interests, as well as the synagogue.

Could you share with us an encounter with a researcher or historian which marked you particularly?

In light of the forthcoming Greek Chairmanship of IHRA, the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance, an international alliance of 34 member countries, that aims to unite governments and experts to strengthen, advance and promote Holocaust education, remembrance, and research worldwide and to uphold the commitment of a world that remembers the Holocaust, of a world without genocide, I would like to mention my encounter with Prof. Yehuda Bauer, historian of the Holocaust and Academic Advisor of IHRA.

It has been my honour to have participated in the biannual meetings of the IHRA since the very first one in Stockholm in 2000, as a member of the Greek National Delegation, serving in the Museums & Memorials Working Group of the organisation and undertaking the position of chairperson of the WG in 2014, during the British Chairmanship. This is how I came to meet Prof. Bauer and partake of his wisdom and his insightful analyses on the dire phenomenon of the Holocaust. His deep understanding and conviction in its educational and social value for the contemporary world has been a crucial source of inspiration and motivation for me.

In the past 20 years, the JMG initiated Holocaust Education in Greece and continuously works with the Ministry of Education at the forefront of all relevant initiatives and actions, pioneering effective programs for Holocaust Education, teacher training seminars and the creation of new content for schoolbooks. In the heart of this significant effort, lay the words of Prof Bauer: “Never be a victim, Never be a perpetrator, And never, ever, be a bystander”.