Portugal became an autonomous kingdom under Afonso Henriques (1109-85), son of Henry of Burgundy, a prince of French origin. The history of its Jewish population differs from that of the other Jews on the Iberian Peninsula. Afonso I was aware of the importance of the Jewish communities he had freed from the Muslim yoke and granted them his protection, putting the chief rabbi, Yahia ben Yahia, in charge of collecting taxes.

Until the end of the fourteenth century, the Jews were reasonably well protected. The rivalry between the two Iberian kingdoms resulted in the accession of a new dynasty, the Avis. Their reign began a period a great prosperity for the Portuguese Jews, whose ranks were soon swelled by the Spanish Jews who began to arrive in 1391. This golden age for the Jews paralleled Portuguese exploration of Africa and the East Indies, which anticipated the “great discoveries”.

In 1279 the country had thirty-one judarias. Two centuries later there were 135. However, this period was not totally free of tension between Jews and Christians: Portugal’s new merchant class was apprehensive of the influence of the Jews and their capital.

Under the reign of João I (1385-1443), new laws obliged Jews to wear an identifying sign on their clothes and imposed curfews on the judarias. There were scattered outbreaks of violence, like the attack on the Lisbon judaria in 1445, in which many died. Many Jews subsequently converted. When the Catholic monarchs passed their edict of expulsion, King João II allowed the Jews to enter Portugal, offering a limited stay of eight months on payment of eight cruzados per head. Portugal estimated Jewish population of 30,000 was thus swollen by some 30,000 to 60,000 Spanish Jews, the new total representing between 6 and 10% of the kingdom’s entire population.

Until 1496 the Portuguese government steered an ambivalent course between the need to conciliate its powerful neighbor and a concern to keep a still-useful minority within its borders. After a series of extremely harsh measures, with children being separated from their parents to be brought up in the Christian faith, and considerable pressure on adults to convert, a decree of expulsion was issued in December 1496. However, lacking the number of ships needed to ensure their departure, King Manoel I decided to convert all the Jews to Catholicism in one comprehensive ceremony.

Furthermore, in 1499 he closed the border to prevent them from crossing. He thus created a society of cristãos novos (new Christians) whose destiny was quite different from that of the Spanish conversos. For, in spite of the apparent unity of the two Iberian kingdoms, their ways of dealing with their Jewish population were very different.

These “new Christians” formed an homogenous group who occupied important positions in Portuguese society while continuing to maintain their own cultural traditions. They came to form a separate nation, and they were called “men of the nation”, or, after settling in Bayonne and Bordeaux, “Portuguese nation”.

The Inquisition of 1547 authorised the prosecution of cristãos novos who still practices Judaism and, later, of the crypto-Jews.

It was carried out with varying degrees of conviction. The union of the two kingdoms from 1580 to 1640 under Philip II of Spain facilitated contact between conversos and cristãos novos, who were linked by family and commercial networks far beyond the peninsula to Bayonne, Bordeaux, London, Amsterdam, and the Ottoman Empire, where the Portuguese-Jewish diaspora was present.

Portuguese exploration opened new horizons for the kingdom, not least for the Jews, many of whom settled in the Americas. They also participated intellectually in this auspicious period: the rabbi Guedella Negro was made physicist and astrologer to King Don Duarte for the period 1433-1451; Jafuda Cresques, also known as Jaime of Majorca, the son of the cartographer and inventor of instruments of navigation Abraham Cresques, was asked by the infante Henry the Navigator to train navigators; Abraham Zacuto, from Castile, published a perpetual almanac in 1496 used on many voyages, including Vasco da Gama’s to the East Indies in 1497. Printing works flourished, including those of Eliezar Toledano in Lisbon and Samuel Orta in Leiria.

Interview with Jean-Jacques Salomon, vice-chair of the Hagada Association, in charge of the Tikva Jewish Museum of Lisbon

Jguideeurope: Recently, there has been a growing interest in Portuguese Judaism, has this helped the evolution of the Tikva Museum project?

Jean-Jacques Salomon :There is no doubt that the multiplication of scientific and historical research and publications on the subject of Portuguese Jewry associated with that of the Crypto-Jews, especially in Europe and the United States, has triggered a growing interest at different levels of the Portuguese, but also European and American cultural and educational world.

In Portugal, the municipalities, especially those involved in the Red de Judarias, the Ministry of Culture (which awarded our Association the label of “Cultural Interest”) and even the Presidency of the Republic, are all showing interest. Obtaining the label of Public Utility for our project is considered a formality. The strong development of cultural tourism in Portugal, before and after the pandemic, has also played its part.

How did Daniel Libeskind become involved in the project and what is his architectural vision for the Museum?

Following the proposal of the Lisbon Municipality in March 2019 to award us (at the time we were simply the representatives of the Association of Friends of the future Alfama Museum) a plot of land of more than 6,000 m2 facing the Tagus and the Belem Tower, we immediately decided to raise our ambitions. Calling on a great international architect was the first step. An appearance at the Congress of American Jewish Museums (CAJM) in March 2019 put us on the path to Daniel Libeskind.

His visit to Lisbon two months later convinced us and the representatives of the Lisbon Municipality that he was the right man for the job.

What was Libeskind’s architectural vision for the museum and how was it received by the Portuguese authorities?

In line with much of his work on the duty to remember, as symbolised by the fractured plans of the Jewish Museums in Berlin, Dresden, San Francisco and Manchester, Daniel, on his first visit to Lisbon, imagined reproducing the word Hope (Tikva) in the Museum building. One of the most representative of the thousand-year-old history of Portuguese Jews, made of Light and Shadow. His first sketches in October 2019, making the letters of Tikva, in Hebrew, the only dividing walls of the building, immediately won over the representatives of the Lisbon Municipality and the Hagadá Private Law Association, created to develop the new project.

Yet it was not until the nineteenth century that Portugal’s Jews were able to express their identity openly and live freely. Between 1820 and 1830, Jewish families from Morocco came to live in Algarve and in the Azores. In 1860, a synagogue was built in Faro. In 1904 the Shaare Tikvah (Gates of Hope) Synagogue, still in use today, opened in Lisbon. In 1920 Captain Barros Bastos founded the Jewish community of Porto and embarked on a campaign to persuade crypto-Jews to return to the Judaism of their ancestors. Working almost single-handedly, he organised circumcisions, published a journal, held talks, set up a school a built a superb synagogue. Opened in 1936, it continues to be used for worship. Unfortunately, Bastos was attacked by Portuguese fascists and a military tribunal condemned him on trumped-up charges; only in 1997 was his name rehabilitated. During this same period the engineer Samuel Schwartz made the surprising discovery of a crypto-Jewish community in Belmonte (Guarda province), all but forgotten by both Judaism and history.

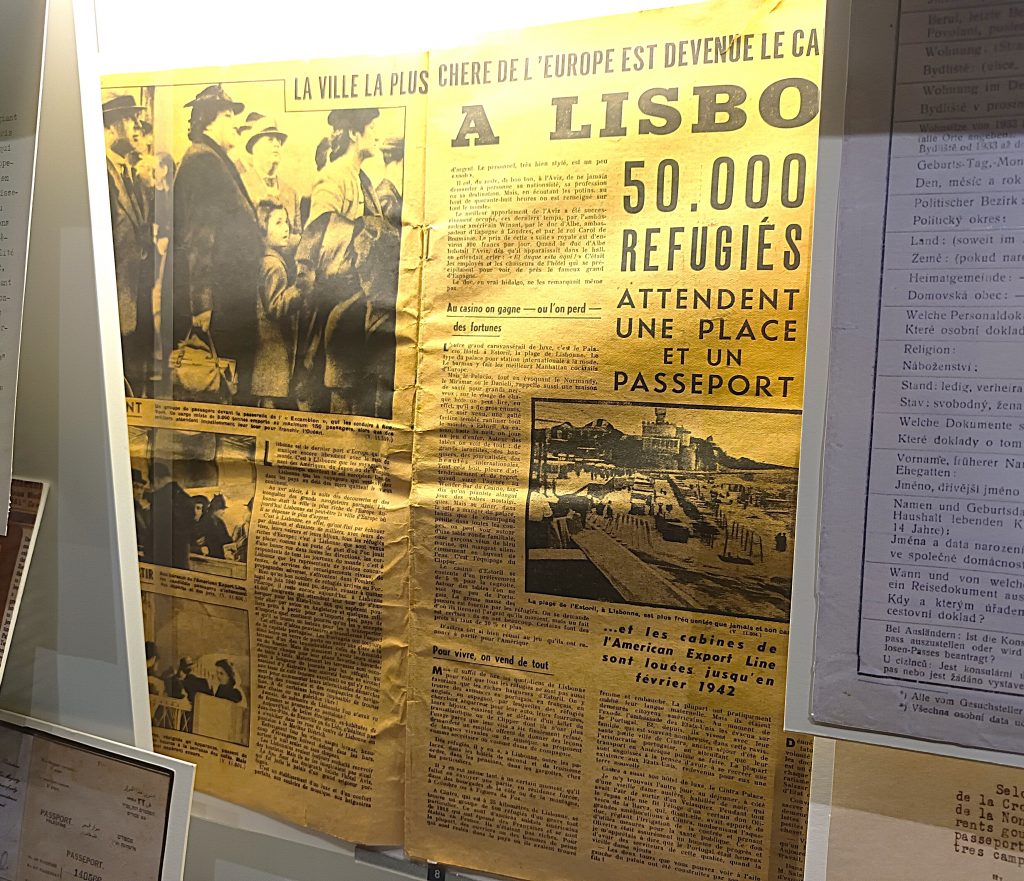

After his posting to Bordeaux in 1940, the consul Mendes Sousa perceived the Nazi threat and set about providing visas for refugees. His work during the weeks of the French collapse saved several thousand mens and women from death. He was nonetheless discharged and discredited by the authorities, and died in poverty. In spite of Salazar’s sympathy for the Nazis, Portugal remained neutral during the war and protected Portuguese Jews while providing support for those who managed to cross its borders. In 1948, with the agreement of the government, the American Jewish Joint Committee set up a camp to receive and organise the transit of Jews to the United States.

In 1977, the new Portuguese democracy established diplomatic relations with Israel. In 1993, the first stone was laid for the Belmonte Synagogue. It opened in 1996 as part of the ceremonies commemorating the expulsion of December 1496. Today, there are several thousand Jews living in Portugal, mainly in the major communities of Lisbon, Porto, and Belmonte but also dotted around a few other towns.

Created in 1992 by Anne Lima and Michel Chandeigne, the Chandeigne publishing house specializes in travel writings and the Lusophone world. It has published many works of reference on Jewish heritage by authors such as Carsten Wilke, Samuel Schwarz, Yosef H. Yerushalmi and many others in its collection “Péninsules”. Celebrating the many events occuring this year in Portugal, we have interviewed Anne Lima.

Jguideeurope: Where did the idea come from of enabling your readers to (re)discover the Portuguese Jewish Heritage?

Anne Lima: It’s through our work on the history of European naval expansion, particularly with our collection « Magellane », that we became interested in the encounter between the three monotheistic religions and the three cultures which have lived together for centuries in Spain and Portugal. Our series “Péninsules”, which has been created almost 20 years ago, is dedicated to the study of that cohabitation. While we studied the inter-religious outlook, it was impossible not to notice the extraordinary richness of the Jewish culture in Portugal, of which certain aspects of this history remain little known and differ very much from its neighbor, Spain. Concerning the Marranos for example, the history, development and heritage reveal a very special Portuguese feature, thus leaving multiple traces, notably in the North of the country where many crypto-Jewish communities have been discovered in the early 20th century.

As you claim, the study of the Marranos phenomenon is a difficult topic and quite different concerning each country. Among the books you publish on that topic, we can find Sefardica, written by Yosef H. Yerushalmi. Why did it become a canonical study of the Marranos phenomenon?

First of all, as we know today, Yerushalmi’s contribution goes way beyond Jewish studies. Sylvie-Anne Goldberg, referring to his book Zakhor, claims that Yerushalmi « has initiated a vast examination of history’s role in modern societies, by questioning its relationship with collective memory ».

Regarding the Marranos, one of Yerushalmi’s biggest credits, as is pointed out by Yosef Kaplan is the breaking down of barriers he undertook by contextualizing the Marrano epic within the crisis of European conscience at the beginning of the modern era. For example, in one of the articles included in Sefardica, « Assimilation and racial anti-Semitism: the Iberian model and the German model », Yerushalmi doesn’t hesitate to draw parallels between the politics of blood purity and the Nazi definition of a Jew: « The purity of the blood substituted for the purity of the faith. » Finally, according to Nathan Wachtel. Yerushalmi is a pioneer when he underlines both Marrano modernity and that of the Iberian inquisitorial system, to the extent that the denunciation system as well as the inquisitorial methods heralded the police rationality of contemporary totalitarian regimes.

Which place linked to the Portuguese Jewish heritage has had a particular impact upon you?

My discovery of the Jewish and Marrano world in Portugal occurred in the 1980s. It was the result of my history studies, as well as of a friendship with Livia Parnes who at that time prepared a PhD on the Marranos in Portugal and of a family rooting in Beira Alta, a region presenting a rich Jewish and Marrano heritage. The three cities or villages which have left the biggest impact upon me and gave me the will to expand our series “Péninsules”, are Belmonte, Trancoso and Guarda.

The incredible story of the discovery of Marrano families in the village of Belmonte in 1917 by Samuel Schwarz, a Polish mining engineer, was undoubtedly decisive for this place all along the 20th century and continues to be so today. The impact of this Discovery goes beyond the religious phenomenon: it affects the social and political relations of the city, changes the cultural landscape, contributes to academic research (new chairs in the region) and influences tourism and financial investments. Nevertheless, the discovery wasn’t limited to Belmonte. Samuel Schwarz’s discovery was followed in the 1920s by an extraordinary movement of “return” of the Marranos to Judaism, entitled « Work of Redemption ». It was carried out during many years by an outstanding man, Republican captain Artur Carlos de Barros Basto. Residing in Porto, he led the movement which had an immense effect and left tangible traces in numerous cities and villages in the regions of Beira Alta and Trás-os-Montes, such as Trancoso, Bragança (where one can stroll down the Rua dos Judeus), Covilhã, and Porto (the Mekor Haïm synagogue, konwn today as the Kadoorie synagogue, was built at that time).

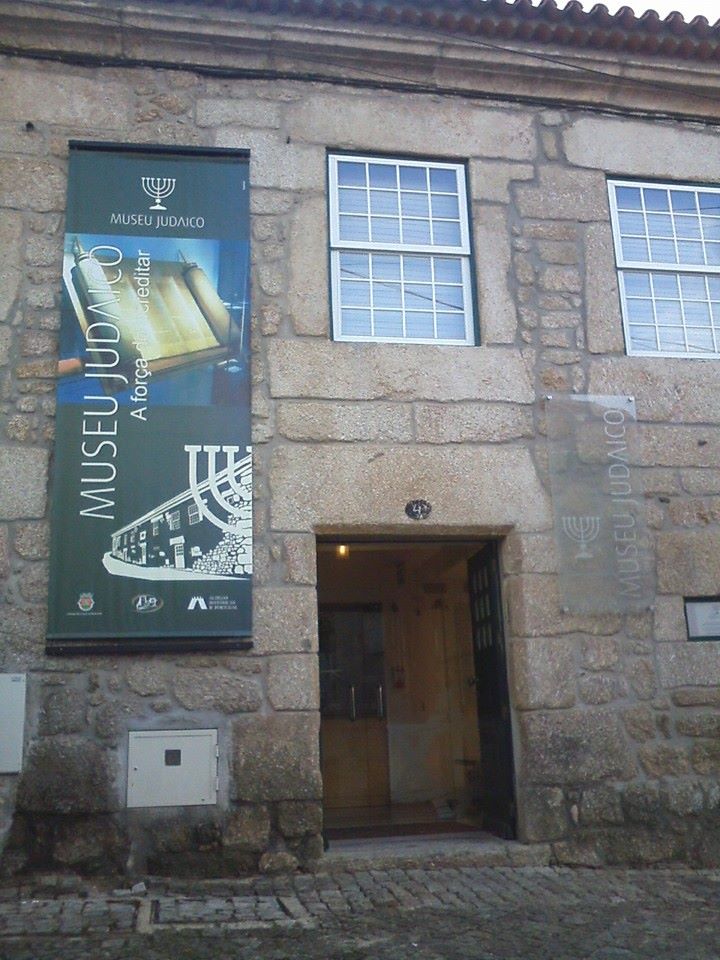

Tomar, in the region of Santarém, is yet another place where Jewish cultural heritage is particularly striking. In that city of the Templars, we can find what seems to be the oldest synagogue of Portugal, dating back to the 15th century, before the forced conversion of the Jews (1497). The building was discovered by Samuel Schwarz (in 1923), and it’s again thanks to him that such an exceptional heritage was saved. Despite many incidents, and after long years, the synagogue was completely restored and solemnly inaugurated this year in the presence of representatives of the city and Jewish studies specialists.

Can we notice differences among the cities concerning such curiosity and will to share?

No doubt. The jolts in Belmonte which already started in the 1920s and even more so in the 1980s, after the (re)discovery of the Marranos, have given rise to the creation of an embryonic Jewish community, with all the particularities and the complexity it entails.

On the other hand, cities such as Tomar or Castelo de vide, where Jewish history and heritage are very ancient, experience only a touristic appeal and have been completely deserted by Jews for numerous years.

Has granting the citizenship to descendants of Portuguese and Spanish Jews who request it changed the perception and attendance levels of this cultural heritage?

Since the law has come into effect, we reckon that more than 37,000 Sephardic Jews have requested the Portuguese citizenship. Most are between 20 and 45, coming from Turkey and Israel, but also from Brazil, Argentina and the US. So far, almost 8,000 of them have obtained a Portuguese passport. Of course, such a passport makes it easier to enter European soil. According to some Jews in Porto and Lisbon, the impact of the Law is already « visible », particularly by a kind of “Jewish tourism” which it enhanced. One can indeed regularly read in Portuguese newspapers accounts on visits and visitors who come in situ in a way in order to assess the would be commitments and engagements involved (regarding to rights, taxes, etc.).

Belmonte remains an emblematic case. This new form of tourism forces the municipal authorities to take initiatives as the return on investment may prove to be rewarding. The main problem being, in Belmonte as well as Tomar, that there are probably not enough resources yet. Thus, we witness punctual operations, deprived of any global thinking, or a structured program for the long term. Finally, the situation in Belmonte is undoubtedly more complex, from the perspective of the Community leadership and the religious representatives. The rabbis often stayed too short of a time in order to grasp the high stakes which represent the needs of this particular community.