The Estonian Jewish community is the smallest of the Baltic states, and, historically, the one that played the least important role in Yiddishland before the Shoah. Indeed, the community never counted more than 4,500 members.

Although present in Estonia since the fourteenth century, the Jews did not assume permanent residence in Estonian territory until after 1865, when the czar abolished the decree forbidding them to live there.

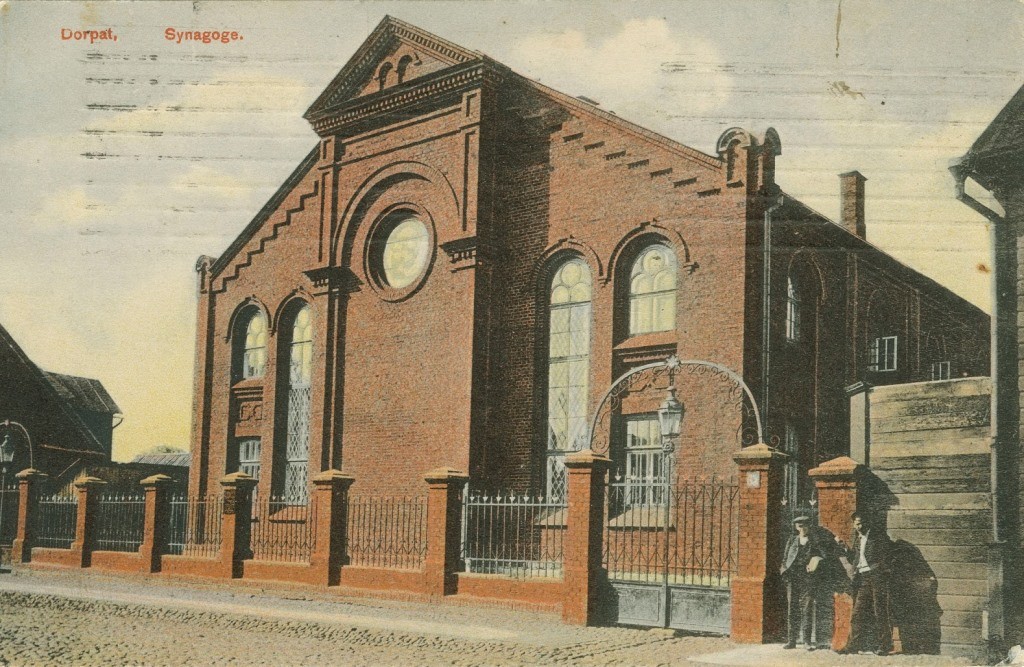

The cantonists, Jewish soldiers serving in the imperial army, established the community in Tallinn in 1830; that of Tartu was begun in 1866. Synagogues were built in the two cities in 1883 and 1900, respectively; both burned down during the Shoah.

Nothing remains of the small Jewish communities of Narva, Valga, Pärnu, and Viljandi, which were destroyed during the war. Jews in Estonia today are in large part Russian-speaking Jews who arrived after 1945.

During the interwar period, independent Estonia treated its Jewish minority fairly. Jews enjoyed all the civil liberties granted to other Estonian citizens, and beginning in 1925, cultural autonomy as well. A minority chose to settle in Palestine, where they contributed to the foundation of two famous kibbutzim: Kfar Blum and Ein Gev.

The 1940 Soviet occupation of Estonia put an end to all Jewish communal life: 400 Jews were sent to work camps. The Nazi invasion in July 1941 succeeded in exterminating the community, whose members were killed by the Einsatzgruppen with the active complicity of local collaborators, most notably militants from the Omakaitse Fascist movement.

After 1945, the Soviet state outlawed all forms of Jewish cultural activity; all that remained was a small community that maintained the cemetery of Tallinn (which still exists). In contrast, one of the effects of anti-Jewish Soviet policy in terms of higher education was that Jewish students from Moscow, Leningrad (Saint Petersburg) and Kiev went for their studies to the University of Tartu or the Polytechnic Institute of Tallinn, which were considerably more open.

Also, during its Soviet occupation, Estonia was a relatively accessible open door for the refuseniks heading toward the United States or Israel. The Jewish community in nearby Finland had helped and continues to aid many Estonian Jews.

Jewish life in Estonia began again in 1988 with the creation of a Jewish Cultural Society and later a school in one of the locations of a former Jewish gymnasium. Since Estonia’s independence in 1991, the Jewish community has become openly active. It scarcely numbers 1,000 people (mostly of in retirement age) according to official Estonian sources and 3,000 according to Jewish sources.

In October 1993, a law granting economy was passed. Unlike the tendencies in Latvia and, to a lesser degree, in Lithuania, the former Estonian Waffen SS receive absolutely no official or public support, and the extreme right is hardly visible.

Interview with Shmuel Kot, Chief Rabbi of Estonia

Jguideeurope: How do you perceive the evolution of the Jewish community in Estonia since you moved there more than twenty years ago?

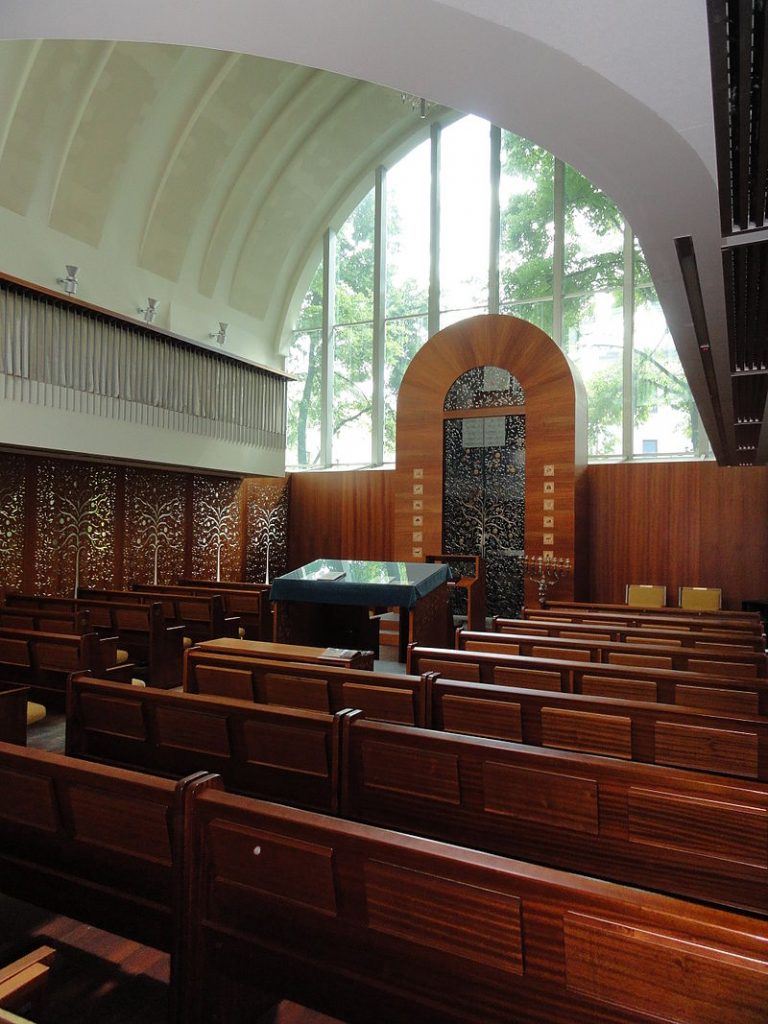

Shmuel Kot: The community is growing from different perspectives. Religiously, culturally and on the organizational level also. The synagogue has been located in a contemporary building for the last 15 years. We have nice activities every Shabbat, with different kinds of guests invited to participate. During the holidays, we provide lessons for Talmud Torah for children as well as for adults.

Do you feel that the community has developed a more professional and official role with its development?

Yes, definitely. Jewish life today offers a vast diversity of possibilities to be enjoyed. Most of our members are Russian speakers, but we also have an important group of French members. Just before COVID, due to the growing number of French members, someone donated twenty prayer books in French-Hebrew. Jewish life is very different in the winter and the summer. During the winter, there is almost no daylight. People are more active inside. During the summer, Shabbat can start sometimes at 11PM! The night of Shavuoth where Jews study all night, has also to be readapted. Life is very nice here. People can be Jewish very openly, there’s no anti-Semitism, and the relationship with the Muslim minority is also good.

Are there new ways of sharing Jewish heritage?

The country makes many efforts in its sharing. And places related to the bright and dark pages of that heritage are shared today. The oldest cemetery was destroyed by the Russians a long time ago. A new cemetery has been opened and is still used today. The Jewish Museum offers a good description of that evolution, displaying the early history of Jewish life in Estonia in the 19th century with young Jewish soldiers settling, the era of prosperity of Jewish cultural life between the two World Wars with, for example, the Maccabi events and the tragedy of the Holocaust.

Estonia was both the first country to grant Jews cultural autonomy in the 1920s, and, on the other side, the first to declare itself Judenfrei during the Holocaust! The museum also displays Jewish life during the Soviet era.

Are you often contacted by persons outside of Estonia wishing to know more about Jewish historical facts and questions about genealogy?

Every day! People contact us for various research. Some archives that we have made available to the public and others that are kept by local authorities, which we try to obtain for them. The Estonian government is making many efforts to enable the gradual availability of those documents online. We just discovered that someone in our synagogue was adopted and found out his Jewish roots thanks to such documents.