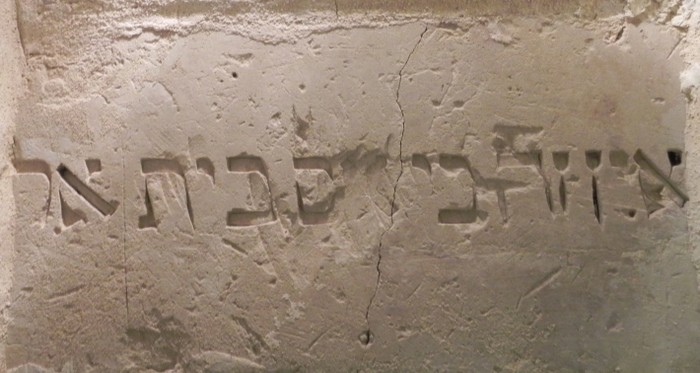

The excavations at Ostia, once the great imperial port of ancient Rome, have revealed the remains of an antique synagogue whose columns support capitals adorned with menorot, the traditional seven-arm candelabra of the Jews. Constructed toward the middle of the first century, perhaps even before the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, the synagogue attests to the more than 2000 of Jewish presence in Italy, especially in Rome. In the Eternal City, the synagogue preceded the Vatican. “Among the groups of Jews who emigrated from Palestine to settle in Europe, those who chose Italy are not only the most ancient, but also the only Jews who never had an interruption in their occupation of this new place of residence”, writes Attilio Milano, the author of Storia degli Ebrei in Italia (The History of Jews in Italy). According to Milano, long ago during fasting periods the Jews of the peninsula celebrated their adopted land as “the island of the divine dew”, a rather liberal translation of the three Hebrew words I-tal-yah.

Although no specific supporting evidence exists, the first Jewish communities are thought to have settled in Rome and some urban centres of southern Italy beginning in the second century B.C.E. The first official contacts were made in 161 B.C.E. when Judas Maccabeus, then struggling to liberate Palestine from the Syrian dynasty of the Seleucids, send two ambassadors to the Roman Senate to ask for aid. The appeal had no immediate outcome because the rebellion was rapidly crushed. In the next century, however, Rome increasingly implicated itself in Judaea’s affairs, until in 63 B.C.E. Judaea was finally conquered by Pompey and became a Roman protectorate. Thousands of Jews were brought to Rome as slaves, but on the whole, they obtained their freedom rather rapidly. The Jews’ refusal to work on Saturdays and their dietary demands made them difficult to manage.

These liberati increased the numbers of their fellow believers in Rome, who were for the most part merchants and artisans attracted long ago by the wealth of the capital city. Their numbers are estimated to have been some tens of thousands in the last years of the Republic. The Jewish community had become a significant population. In the civil war between Pompey and Julius Caesar, the Jewish community whose to massively support the latter, who showed his gratitude by granting them a number of specific rights. They were exempted from military service, and the communities obtained the right to regulate their internal affairs according to their own laws. They were also permitted to collect donations and send a part of them to Jerusalem for the support of the Temple there. According to Roman historian Flavius Josephus, when Julius Caesar was assassinated in 44 B.C.E., the Jews of Rome were among the most numerous to pressure the Forum to honour him who had given dignity to the former slaves.

Augustus confirmed and enlarged the privileges that Caesar had granted to the Jews. In the first years of the empire, the Jewish population in Rome is estimated to have been some 40,000 persons of a total population of 1 million inhabitants. However, the absolutist demands made by Augustus’s successors that everyone worship in the cult of the deified emperor created growing problems. The emperors were determined to apply their demands to all, including the Jews. Caligula was the first to want to install a statue of himself in the synagogues before he was convinced to withdraw his project. Imperial power began to consider the Jews with their incomprehensible religion with an increasingly suspicious light, while their quarrels with Christians were judged stranger still. The Jews’ situation became more delicate when revolts broke out in Judaea, bloodily repressed by Vespasian and his son Titus. In 70 C.E. Titus reconquered Jerusalem, destroyed the Temple of Jerusalem, and took more than 100,000 Jews into captivity. Among other things, he decided the money the Jews had been donating for the maintenance of their temple would henceforth be used to maintain that of Jupiter Capitoline.

The conversion of Constantine to Christianity in 312 and, shortly thereafter, the proclamation of Christianity as the state religion changed the fortune of Jews for the worse. The Church could not refuse the heritage of the Old Testament without thus denying itself; on the other hand it could not readily accept its affiliation with the community without risk of losing the prestige of its status as official religion. It decided that the Jews could continue to practice their religion in the capacity of living witnesses to the truth contained in the Old Testament, but that they should also perpetually expiate their sin of refusing Jesus Christ. In 325, the Council of Nicaea clearly separated the two religions by instituting Sunday instead of Saturday as the obligatory day of rest and creating the first discriminatory measures against the Hews that prohibited them from occupying positions of public governance or possessing real estate.

After the barbarian invasions, the Jews numbered no more than a handful of citizens in a devastated Rome, reduced to some 10,000 inhabitants. Pope Gregory I the Great’s coming to power in 590 reestablished the authority of the Church in the west. The papal bull Sicut Judaeis put in place some measures of protection for the Jews. Throughout the Middle-Ages, Italian Jews experienced alternating periods of persecution and relative tranquility.

The travels in Italy chronicled by Benjamin of Tudela, a Jews from Navarre, give us a good idea of Judaism on the peninsula in the middle of the twelfth century. At the time, there were few Jews in northern Italy, scarcely two families in Genoa, and not many more in Venice. An active community of some 200 families lived in Rome, respected by the rest of the population and not obliged to pay tribute. They worked as artisans and merchants, but also as literary figures and doctors welcomed in the papal court. The Popes did not impose on their city the severe measures applied to Jews in the rest of Christendom.

However, it was in southern Italy, in Naples, Salerno, and above all Sicily, that Jewish communities flourished even more. With more than 8,000 Jews of a population of 100,000, the Palermo of the Norman kings was then the great centre of Jewish life in Italy. They excelled in the production and dying of silk. Born of this pluralistic culture, the emperor Frederic II of Souabe was the first modern prince of Europe at the dawn of the thirteenth century. The great enemy of the Popes, he instituted within his domains of Sicily and southern Italy the first laws protecting the Jews. He recognised especially their essential economic role. These measures did not survive his reign; rather the Fourth Lateran Council (1215) hardened the discriminations against the Jews.

The princes of Anjou and later the Spanish conquered Sicily and southern Italy in their turn, and over time the situation became more difficult for the Jews. Sicilian Judaism was wiped from the map at the same time as in Spain with the order to expel Jews in 1492. In an unusual case, the population and the local government of Sicily, and especially Palermo, protested against the Jews’ arrest and defended them, although with little success. Those expelled left for Naples, whence they were again driven out a few years later.

In the sixteenth century, Italian Judaism was in a completely new situation. In Rome and in the Papal States, the persecutions had become more severe since the middle of the century. In 1555, the newly elected Paul IV released the Cum Nimis Absurdum edict, which, instituting a ghetto for the Jews in Rome, subjected them to difficulties without precedent in the Eternal City. For ready identification, men were forced to wear a yellow hat and women a yellow veil while in the city. Jews no longer had the right to have real estate or Christian servants. Authorised employment was limited to moneylending, and the bank owners no longer had the right to make loans at interest rates higher than 12 percents.

In Rome, as in Ancona and all the territories administrated by the papacy, Jewish communities began to sink into a long night that lasted three centuries. The principal gathering spots for Jewish life, reinforced by the arrival of Jews from Spain, Portugal, or Sicily, subsequently spread to the northern cities of the peninsula thanks to the relative tolerance of the princes or local powers such as the Gonzaga family of Mantua, the Este family of Ferrara, or even Venice, which was, however, the first city to institute a ghetto in 1516. In Tuscany, at first Cosimo I de’ Medici welcomed numerous Jews in Florence and Siena before giving in to papal injunctions against them. His successor Ferdinand I decided to make Livorno a large trading port with the Levant and encouraged Jews to settle there, eventually making this city the ultimate haven of freedom for Italian Jews.

Reverberations of the French Revolution, which for the first time accorded Jews full equality with other citizens, shook up Italian Judaism. Considered as “the natural allies of the French and new ideas”, the Jews were victim to uprisings fomented by the clergy in Livorno in 1790, and in Rome in 1793.

When, in 1796, the soldiers of Napoleon Bonaparte crossed the Alps and slowly but surely toppled the walls of the ghettos as they advanced, they brought with them legal parity for the Jews of the Piedmont, then Lombardy, Emilia, and finally Venice, where the French troops entered in May 1797. Less than a year later, the troops marched on Rome, where the Jews traded their yellow caps for the tricolours of the French flag. The Roman Republic proclaimed: “Jews who meet the prescribed conditions for being Roman citizens will be subject only to the law common to all citizens”. The soldiers swarmed the civil guard, one of whose battalions was commanded by a certain Isacco Barraffael.

When French troops withdrew a year later, retribution was swift and terrifying, subjecting the Jewish communities to harsh punishments. Many Jewish quarters were pillaged. However, in 1800 the soldiers of the tricolour retook control of the peninsula. For fourteen years Italian Jews enjoyed full civil rights. They bought land and opened shops outside the ghettos. A Jewish lyceum was created in Reggio Emilia. After the overthrow of Napoleon, the Congress of Vienna tried to turn back the clock a quarter of a century. Pope Pius VII returned to Rome, the Austrians to the north of the peninsula, and the Bourbons to the south. But the Restoration could not eradicate the new ideas. Italy discovered itself as a nation and the Italian Jews as free men. The Jews played an active part in the conspiracies and struggles that finally led, a half century later, to the unification of Italy under the guidance of the Piedmontese monarchy.

On 20 September 1870, Italian troops entered Rome through a breach in the Porta Pia, putting an end to the temporal reign of the Popes and thereby achieving the complete unification of the country. Rome’s ghetto was eliminated. The Jews of the new capital became, like their follow believers in the rest of the peninsula, separate but full citizens. Jews’ attainment of full equality occurred later in Italy than elsewhere in the west, but they soon enjoyed conditions that “could not have been better”, as Cecil Roth emphasises in The History of the Jews in Italy, and assumed important roles in the new kingdom. Isacco Artom, personal secretary of the Piedmontese prime minister Camillo Cavour between 1850 and 1860, was the first Jew to occupy a position of diplomatic importance. Luigi Luzzati, heir to a great Jewish family from Venice, became prime minister in 1910 after having worked in the Ministry of Finance for several years.

General Giuseppe Ottolenghi, a Piedmontese Jew, was chosen by the king as a professor of military science for the crown prince before he became minister of war in 1903. Ernesto Nathan, a Jew and a grand master of the Freemasons, was the mayor of Rome between 1907 and 1913. Numerous Italian Jews made names for themselves in the universities, in music, literature (Italo Svevo, Umberto Saba), and the plastic arts (Amedeo Modigliani). Communities concentrated in large cities built new temples, like the neo-Babylonian Grand Synagogue in Rome, thus demonstrating the harmonious integration of some 45,000 Jewish Italians into the bosom of the nation. Italy was almost entirely without anti-Semitism. Even the Fascists did not play this trump card, at least during the first decade in power.

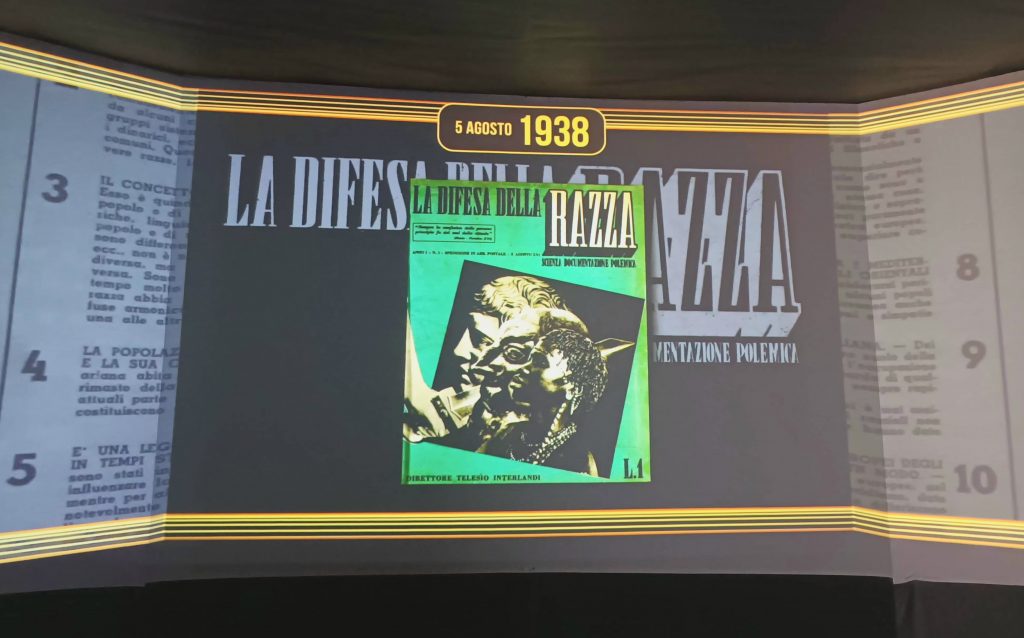

Benito Mussolini never ceased repeating that, in Italy, “there isn’t a Jewish problem”. The Jews were members of the fascio since its creation. Margharita Sarfatti, a refined intellectual, biographer, and political adviser to Mussolini, was Jewish. If in his speeches Mussolini lashed out at “the international Jewish plutocracy”, he maintained relations with certain leaders of the Zionist movement in hopes of reducing English influence in the Near East. After 1933 and Hitler’s rise to power, Fascist Italy welcomed several thousand Jewish refugees fleeing Nazi Germany, who then embarked for Palestine from Trieste. Nevertheless, beginning in the middle of the 1930s, the strengthening of the Rome-Berlin axis gave rise to an anti-Semitic Fascism that was increasingly virulent. It came to a head in July 1938 in the Manifesto of the Race, written in large part under the influence il Duce. Three months later the regime announced the first racial laws that robbed certain Jews of their nationality and banned all Jews from the army and administration. The laws also prohibited Jews’ owning or managing businesses with more than a hundred employees. These infamous laws were rigorously applied. Italian Jews were humiliated, reduced to second-class citizens, but they were not killed.

The Final Solution was put into action after September 1943 in German-occupied central and northern Italy, as well as the puppet Republic of Salo, proclaimed by Mussolini after he was overthrown by the grand Fascist council and the king. The massacres began in a few villages of the north where the Jews had found refuge. Soon after, the killing machine went into full swing. On 16 October 1943 the former Jewish ghetto in Rome was surrounded by the SS and 2000 Jews were taken in three days of mass arrests. The victims, many of whom were children and the elderly, were soon deported. Only fifteen of them would return from the camps. Deportations also took place soon after in Florence, Trieste, Venice, Milan, Turin, Ferrara, and elsewhere. Aided by their fellow citizens, many Italian Jews succeeded in going into hiding, but ever at the mercy of betrayal, Jews had to change shelters ceaselessly. Some Jews managed to reach the Swiss border, while others joined the ranks of the partisans. In all some 85 percent of Italian Jews survived the war, the highest percentage after Denmark.

Close to 35,000 Jews live in Italy today (of a total population of 62 million). The strongest community is that of Rome, which is the most deeply rooted in its dialect, traditions, and cuisine. A number of Jews came from Hungary after the war, but especially Jews from Egypt, Tunisia and Libya settled on the peninsula on the years 1950-1960. The community flourishes economically, with a high level of education and integration. Jewish writers and intellectuals -Carlo Levi, Primo Levi, Alberto Moravia, Natalia Ginzburg, citing only the most famous among them- have been or still are at the forefront of Italy’s cultural life. Anti-Semitism remains almost nonexistent. Its most severe manifestation was the attack perpetrated on 9 October 1982 by Arab terrorists at the exit of the Grand Temple in Rome. A child was killed and forty injured. Since the Second Vatican Council launched by Pope John XXIII, and then by Pope Paul VI, the Church has never been more engaged in Jewish-Christian dialogue, turning the page on centuries of anti-Semitic doctrine. This new dynamic gained expression on 13 April 1986 with the historic visit of Pope John Paul II to the Grand Temple in Rome, where he gave homage in the name of Catholics “to their elder brothers”.