The visitor to Eastern Europe hoping to discover a rich Jewish architectural heritage must remember that what was once the center of Judaic cultural and religious life in Europe -principally in Lithuania between the eighteenth century and the Shoah– had disappeared beyond ruins and cemeteries.

The complete eradication of a Jewish presence, the sworn objective of the Nazis, was conducted with the complicity of a segment of the local population. This was followed by the antireligious policies of the Soviet Union and its series of population transfers and persecutions, reducing to nothingness and incomparable culture and the unique language of Yiddishland. Any Jewish-themed journey into the Baltic countries is therefore first and foremost a matter of archaeology and genealogical research. That said, there is still much to gain by visiting the small communities that have tried, courageously, to bear witness to the past and reveal their Jewish roots to younger generations.

The term Yiddishland is a neologism denoting after the fact a country that never existed as such and which might be described, rather, as a linguistic and cultural space, the place where the Yiddish language was used. The term can thus be understood in its broader sense, with both historical and geographical meaning: it covers the evolution of the Yiddish language from its formation by Ashkenazic communities from Germany (the Valley of the Rhine, Moselle) in the tenth and eleventh centuries, its migration across Bohemia through Poland and Eastern Europe, and finally its transfer in the late nineteenth century to cities like New York, Antwerp, Paris (around rue des Rosiers), Buenos Aires, and others.

In its most common usage, however, Yiddishland refers to the extension of Yiddish across eastern Europe, as much in space as in time, as it actually evolved and was spoken by nearly all the members of the Jewish communities here. This was the case in Poland, Lithuania, Belarus, Ukraine, Bessarabia, Moldavia, and in sections of Hungary and Romania from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries to the mid-twentieth century.

A map of the Polish Union before 1772 (the date Poland was first divided), which stretched northward to the gates of Riga, eastward as far as Vitebsk, southeastward to the gates of Kiev, and southward to Lvov and Polodia, roughly described the historical boundaries of Yiddishland, for this was where speakers of Yiddish were concentrated. Formed upon a Germanic background (it evolved from Middle High German) and coupled with many Hebrew words (around 10% of the vocabulary), Yiddish also absorbed over the course of its history a fair number of slavisms (another 10 to 15% of its vocabulary) of Polish or Russian origin.

After the division of Poland let to that country’s disappearance between 1795 and 1918, Yiddishland was almost completely integrated within the Russian Empire (with the exception of Galicia, Bukovina, sub-Carpathian Ukraine and Transylvania, which all fell within Austria-Hungary) and hemmed inside the tcherta osiedlosti (residential zone), after a ukase issued by Catherine II imposed significant restrictions on movement, notably a ban on entering central Russia, Saint Petersburg, and Moscow. This state of affairs remained unchanged until the First World War.

The centers of Yiddishland were Vilnius (the “Jerusalem of Lithuania”), Warsaw (the Muranów district), Kraków (the Kazimierz suburb), Lódz (northern and central neighborhoods), Minsk, Lvov, lasi, Kishinev, Czernowitz, and Odessa. This “nation” was characterized most of all by the shtetlach, small rural towns where Jews were a majority within clearly defined neighborhoods centered around the synagogue and the narketplace, where the community gathered and traded with the non-Jewish world as well. There existed countless shtetlach, whose names still vividly evoke Jewish life in the region: Lubartów, Chelm, Szczebrzeszyn, Wlodawa, Zamósc, Raziechów, Sambor, Drohobycz, Brody, Belz, Bursztyn, Brzezany, Kremenets, Sadgora, Kossov, Wyznitz, Czortków, lasi, Bershad, Berdichev, Pinsk, Borboujsk, Baranovichi, Slonim, Vitebsk, Dvinsk, Tykocin…

In each of these towns can still be found traces of times past: synagogues, cemeteries, marketplaces, old mikva’ot, typical houses with galleries and rectangular courtyards- a certain spirit of the place that endures even after the extinction of its residents. Architecturally, one of the best preserved examples is found in Tykocin, near Bialystok, with its two Christian and Jewish districts clearly demarcated, the synagogue and church at the center of each neighborhood, the marketplace between the two, and the two cemeteries at the far ends.

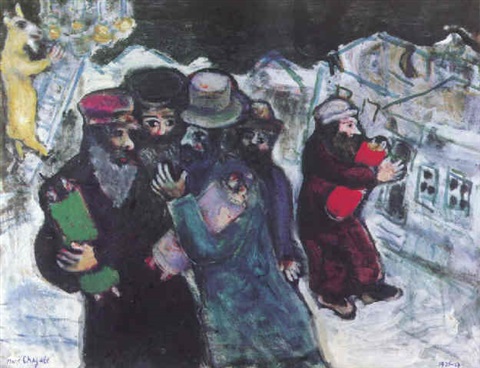

The shtetl was the birthplace of a rich culture that, beyond folklore, achieved veritable nobility and formed a common heritage: Yiddish literature through nineteenth-century founders Sholem Aleichem, Itzhak Leybush Peretz, and Mendele Moykher Sforim and twentieth-century poets such as Glatstein, Gebirtig, and katzenelson, as well as the works of Nobel Prize winner Isaac Bashevis Singer; painting depicting life in the shtetl, culminating in the masterpieces of Chagall; photography by Vishniac or even Alter Kacyzne; music through Yiddish songs (like “Mayn Shtetele Belz”, “Di Yiddishe Mame”, “Kinderyorn”, “Az der Rebbe Tanzt”, and “Rabbi Elimelech”) but especially through musical comedies like Fiddler on the Roof (or Anatevka) by Jerry Bock or, more generally, the Klezmer tradition, which is experiencing a strong revival today. All these artistic expressions have idealized the shtetl in present-day consciousness as a place of well-being, a warm atmosphere with its joys and sorrows, an idealization all the stronger now that this world is forever lost, swallowed up for eternity by the Shoah.

Life in the shtetl was far from idyllic: Jews suffered unemployment, insecurity, pogroms, and ignorancem resulting in heavy emigration, from the late nineteenth century through the 1930s.

In northern Yiddishland (Lithuania, Belarus, northeast Poland), the Gaon of Vilna (now called Vilnius) had a determining influence on Jewish life, in the form of an orthodoxy respectful of the letter of the law and the commandments, but open to a certain form of rationalism (the Haskalah). In southern Yiddishland (southern Poland, Ukraine, Bessarabia), Hasidism began to develop in the mid-eighteenth century, a mystical, anti-Enlightenment movement seeking to revive Judaism’s original fervor by sending its practitioners into trances and promising immediate contact with God. It was centered around the charismatic tsadikim, who in turn built around themselves veritable courts and a new form of orthodoxy.

Today, Yiddishland exists only in memory, in its intellectual creations and the artistic and cultural expressions, and in the hearts and songs of those who strive to breathe life back into both its spirit and letter. Revisiting this bygone world resembles an archaeological dig through both real terrain and memory itself.