Few Jews lived in Mechelen before the war, but the city is infamous in Jewish history for the Kazerne Dossin. This building dates from before Belgian independence, from Austrian times. At the beginning of the 20th century, it served as a military barracks for the Belgian army. In 1942, when the Nazis were looking for a place to round up the Jews, they chose the Kazerne Dossin.

It seemed convenient because of its military configuration with a plain in the middle and walls to avoid prying eyes. In addition, there are railways right next to it. Finally, because it is located in the city of Mechelen, halfway between the two cities where the majority of Belgian Jews reside, Antwerp and Brussels.

Once the prisoners had been rounded up, they were taken by truck from Antwerp and Brussels to the Kazerne Dossin and then deported by train to Auschwitz. The first deportation took place in August 1942. When Belgium was liberated in September 1944, about 150 prisoners were found to be part of the next convoy. In all, 28 convoys left.

The German soldiers fled to Holland, which was only liberated later. They left prisoners behind, together with the administrative documents. Shortly before they fled, the soldiers had asked prisoners to burn these documents, which was not done. Therefore, a lot of documents were collected as evidence of these crimes. After the war, all these documents were transferred to the military museum. In the 1970s, there were governmental discussions about what would happen to this place. Some politicians wanted to destroy it. Then, in the 1980s, a property developer proposed to turn it into a luxury residence.

The Jewish communities of Antwerp and Brussels united behind Natan Ramet (1915-2012), a survivor of the Shoah, who did a lot of educational work with young people. Together they bought part of the building and transformed it into a memorial museum. This small museum was opened in 1996.

In the 1990s, school textbooks began to talk about the Holocaust and schools began to visit Dossin. These were very emotional moments, as the days organised by the national education system included a visit to the Breendonk camp where political opponents and resistance fighters were imprisoned and executed. As the museum is quite small, the visits became complicated with school groups of sometimes 60 pupils.

The Flemish government therefore supported the project to build a larger museum next to the Kazerne Dossin that would explain the history of the Holocaust in Belgium. It would also highlight acts of resistance and do more educational work on the issues of genocide and forced population displacement.

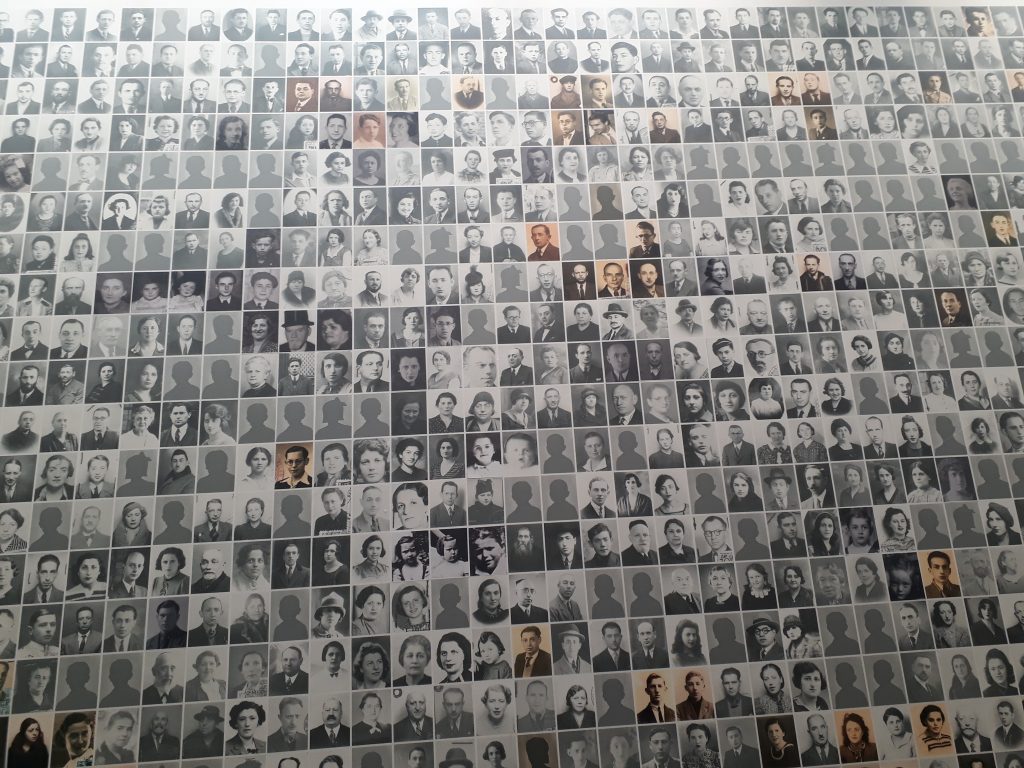

Thanks to all the documents found, Natan Ramet’s daughter, Patsi Ramet, had the idea, together with the former director of the Museum, to put a face to these names. Avoiding them to be seen as mere statistics. She spent years studying the files of the ministries on foreign Jews living in Belgium, 90% of whom were not of Belgian nationality. At that time, all migrants over 15 years of age had to add a photo ID to their file for entering Belgium. With the names on the documents left at the barracks, Patsi Ramet was able to associate many faces. She digitised all these photos, which were published in four books, including 17,000 of the 25,490 Jewish and 353 Roma deportees.

For the minors, the task was much more complicated, as there were no photos in these files. Advertisements were placed in Jewish newspapers around the world and institutions were contacted to find the missing photos.

On the inside wall of the museum are displayed the black and white photos of the more than 25,000 deportees, with boxes including just a profile of a child or adult whose photo has not yet been identified.

The photos of the 1,200 who returned from deportation are coloured in sepia. Regularly, photos are still sent in from all over the world and added during an annual ceremony.

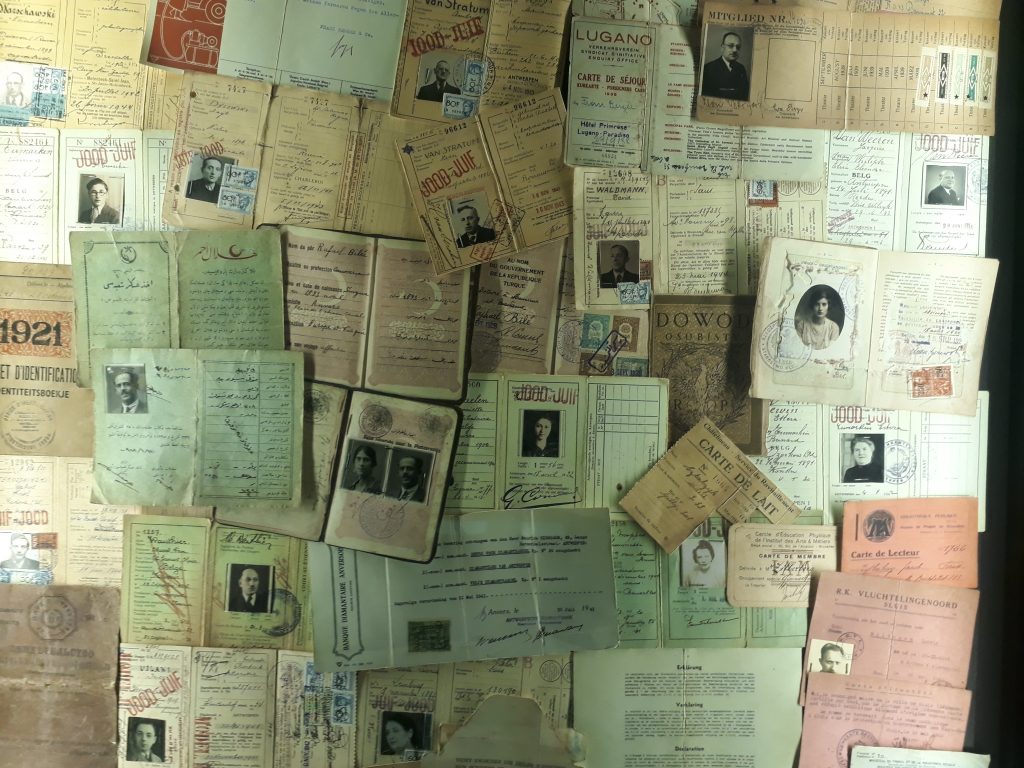

In 1942, when the prisoners arrived, all their documents and possessions were confiscated and thrown away. When the following year the internment camp was run by another Nazi official, the documents were kept in envelopes. Of the 4,500 envelopes found, all the documents have been digitised by historians, trainees and volunteers. Each opened envelope represents a life, a passport, a ration card… and everyday documents, such as a medical prescription or the diploma of a young boy from Liege.

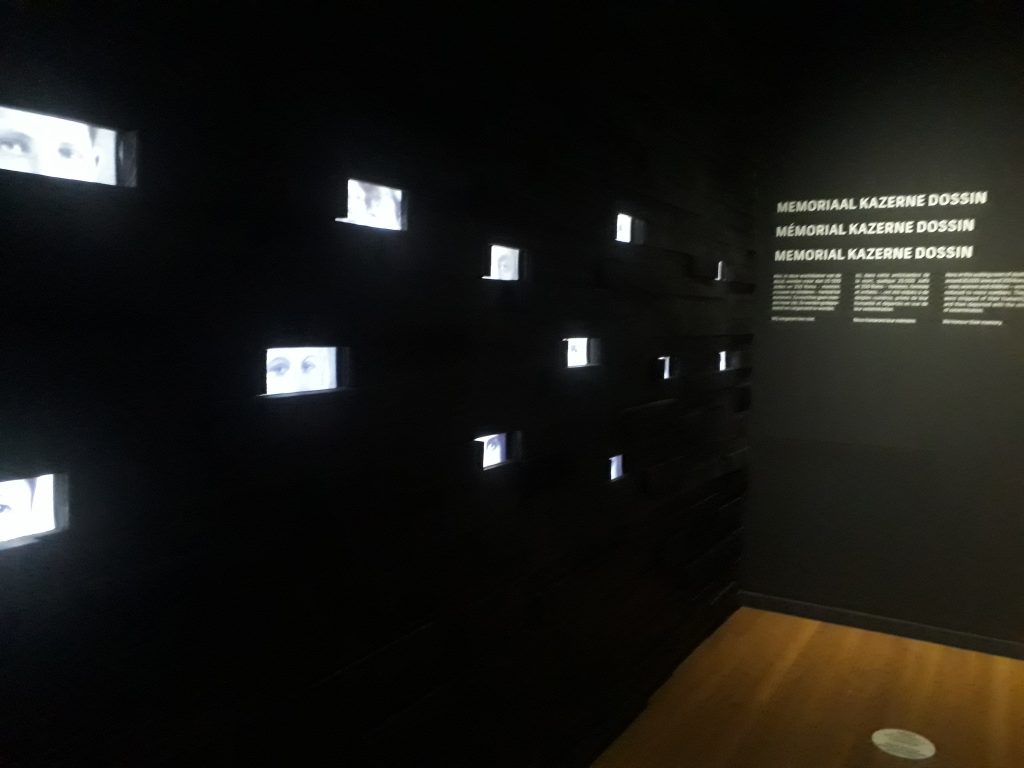

Today, the former Kazerne Dossin has been mostly transformed into luxury flats. The Memorial is located at the entrance to the right of the complex. Once through the front door, you enter a room with photos from which you can only see the eyes as if they were welcoming you.

In the first room, we witness how the Jewish community lived simply, assimilating into Belgian life. Photos in the street, at work, at the beach, of a banality that evokes the carefree nature of the 1930s and the way in which one could say, as the famous French phrase goes, “happy as a Jew in Belgium”.

We discover copies of documents behind glass: identity cards and other administrative papers. In the middle, a typewriter where the names of the arrivals were added by female prisoners used as secretaries.

The women sometimes managed to blur the documents by not writing down certain prisoners, in order to protect them. A projector highlights these names on pages. All these documents have been removed from the envelopes and digitised in recent years.

In the room to the right is a moving work of art by Philippe Aguirre Y Otegui, a Spanish Basque artist whose family fled during the civil war. The work is entitled ’15 August 1942′, the date of the first major round-up in Antwerp, and shows a family hiding under a table.

Then we see images of Nazis bullying Jews by shaving them and painting the swastika on them to amuse their fellow photographer. And this terrifying photo, the only one found of the interior of Dossin showing the arrival of the Jews in the camp. Nearby, drawings (notably by Irène Spicker) and paintings, in their own way, immortalised the feelings of the prisoners and preserved the testimonies, as well as a very surprising work by children.

The children’s room, in the spirit of the one at the Yad Vashem museum in Jerusalem, is a small room covered with photos of deported Jewish and Gypsy children. A little further on, a small room broadcasts on a screen the testimonies of former deportees who have been recorded, telling how the roundups were carried out.

On leaving the memorial, which was the former museum, you enter the new museum opposite the barracks. Inside, you are immediately struck by the wall of photos that extends over all the floors and by the empty boxes without any photos being found. In front of the photos is a screen that allows you to see the location of the photos according to the names.

On the first floor, the history of Germany from the end of the First World War to the rise of Nazism is presented. With anti-Semitic propaganda leaflets and a dehumanisation of the Jews representing them as insects. And also, a racist poster with a drawing of a black French soldier guarding the borders with Germany. As a welcome image on this floor, a huge contemporary photo of a crowd gathered for a festive event, contrasting with the Nazi manipulation of the masses in the stadiums, symbolising the various collective demonstrations.

Then we discover the Belgian Jewish history. How the Jews have integrated very well into Belgian life, they who originally came from Sephardic lands but the majority who arrived at the turn of the 20th century fled the pogroms of Eastern Europe.

Photos showing youth movements, students, workers and happy Saturday strollers. With stories of Jewish symbols of this beautiful integration, including a general and a great defender of the Flemish language. You can also see the paintings of Felix Nussbaum, deported in 1944, whose studio was burned down and many works destroyed. A museum is now dedicated to him in Germany.

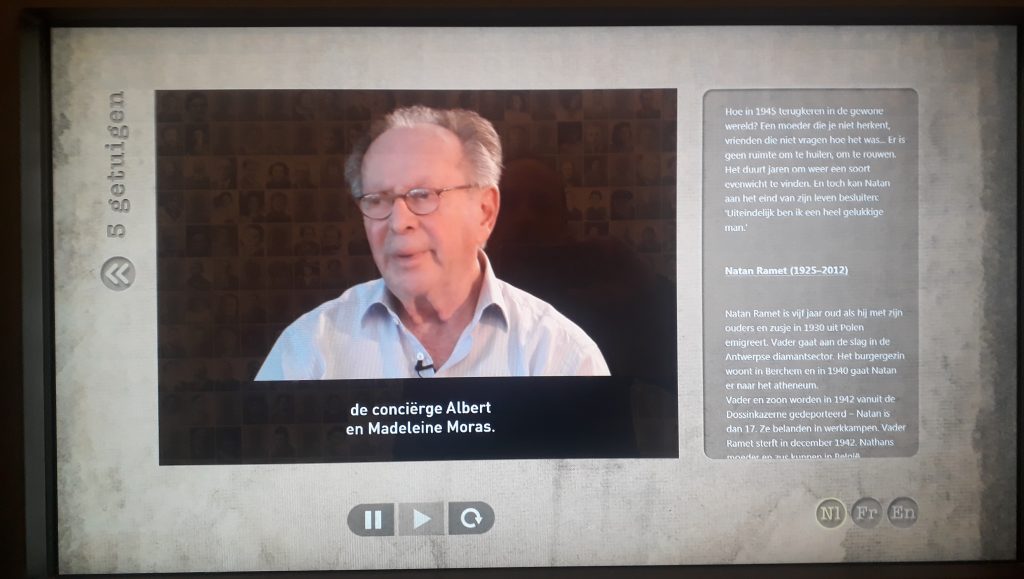

The testimonies of five people are also broadcast: Malvine Löwenwirth, Michel Goldberg and Natan Ramet from Antwerp as well as Simon Gronowski and Marie Pinhas from Brussels. They talk about Jewish life in Belgium before the war, the deportation, the camps and their survival and return after the war, in parallel with the museum presentation.

The general life of Belgians at that time is also described. During the invasion, many Belgians feared that Belgium would definitely become a German province. The occupiers tried to calm the population by “reassuring” them. Then, in 1942, such covering up was not possible anymore when the applied increasingly brutal measures, deporting political opponents. The Walloon authorities showed more opposition and resistance to the Nazis than the Flemish authorities. For example, when Jewish lawyers were forbidden to plead, the city of Antwerp enforced this decision, unlike Brussels.

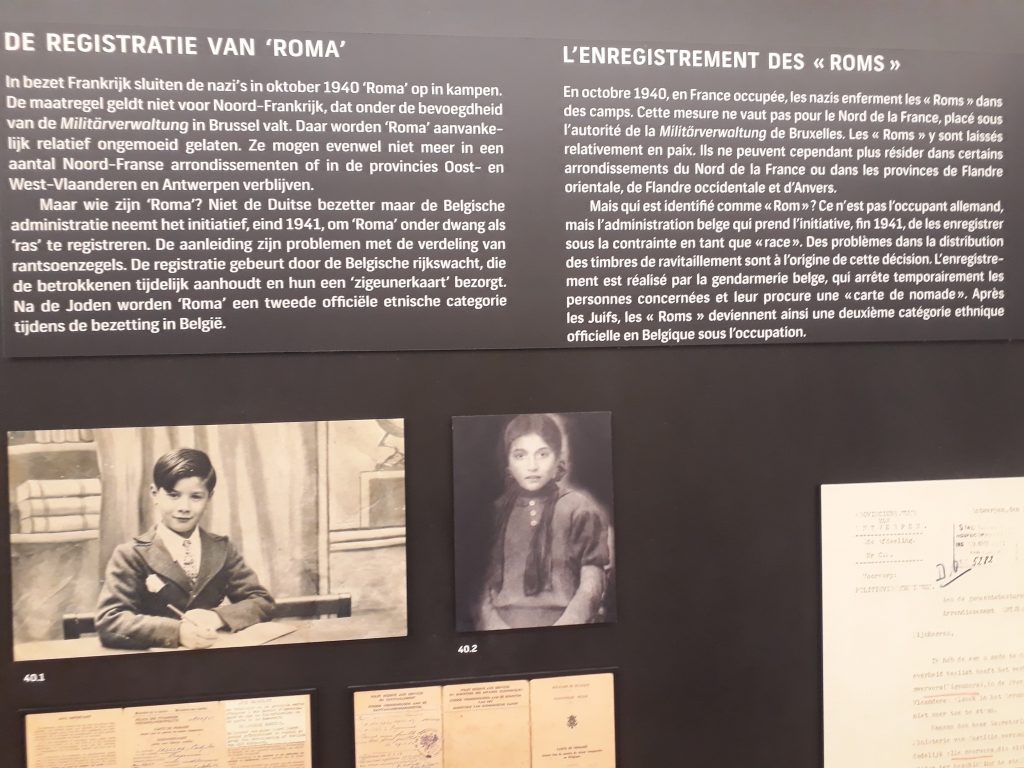

The history of the deportations of the Gypsies is presented on the walls of this floor. Among the photos we can see a family whose son is present in the room dedicated to children in the Dossin Memorial.

On the second floor, we understand how the German occupiers manoeuvred to compile the lists of Jews. In 1941, they decided that Jewish children could no longer attend public schools and had to continue their studies in Jewish schools, which also facilitated the census. How also removal companies participated in the convoys of the population.

On this floor, small stories of the daily life of the Jews who disappeared and the importance of de-socialising and dehumanising them are presented. Like this drawing in two parts, where first the Jews “monopolise” the terraces of a café while the non-Jews observe them from outside and finally, “thanks” to the Germans, the Jews are outside and the non-Jews are enjoying the good times. Also shown, a caricature of Camille Huysmans, the former mayor of Antwerp who opposed the Nazi regime.

Historical photographs show the attack on two synagogues in Antwerp on 14 April 1941 and the broken windows in the Jewish quarter, which represented a Belgian ‘Kristallnacht’. When a mob destroyed the synagogues, long before the ‘authorities’ arrived. We can see a crowd in the pictures seeming to “enjoy the spectacle” and their impassivity.

As a result of these public attacks, the dissemination of evidence of these atrocities by the Resistance, and the mere appearance of the yellow stars, many Belgians began to help Jews hide and fight the Nazi regime with greater zeal. The Nazi regime had previously tried to conceal its actions, to hide them from view, as the thick walls of the Kazerne Dossin, for example, allowed.

From 1942 onwards, acts of resistance multiplied. The Breendonck camp and the very difficult conditions of the prisoners inside are illustrated by photos. They were locked up, tortured and killed. Many pictures of Jewish resistance fighters are also presented.

Maps of Antwerp and Brussels exhibit the neighbourhoods where many Jews lived and where they were rounded up. Testimonies of police officers are displayed, some of them criticising the measures, others supporting them and one categorically opposing such measures.

On the third floor, the disturbing mob phenomena around the lynchings of blacks in the United States and the process of dehumanisation that facilitates and accelerates mass murder are also shown.

The 28 convoys of deportees are then presented, with photos and stories of the victims. Many convoys left as early as August 1942, with the first six transports taking place in three weeks. Among the deportees was a Gypsy woman who had just given birth and was transported with her 39-day-old baby.

During the first convoys, carried out in 3rd class trains, some deportees managed to escape. Tools were placed on the trains and sometimes deportees also escaped with the help of train drivers who slowed down pretending to have technical problems. Thus, 236 managed to escape, some of whom were later found and killed. Following these repeated escapes, from April 19, 1943, the 20th convoy, the Nazis transported the deportees in cattle cars. This convoy was attacked by three young resistance fighters.

The visit of the museum ends with many video testimonies and presentations things such as the uniforms of the deportees, but also a large map with all the places in Belgium where Jewish children were hidden.

The story of how these children were hidden is told by survivors and the courageous people who helped them, who explain how they had to falsify their papers and change their names, not being able to get in touch with their families. Then, disturbing photos of leisure time moments of German soldiers and their henchmen taken by them.

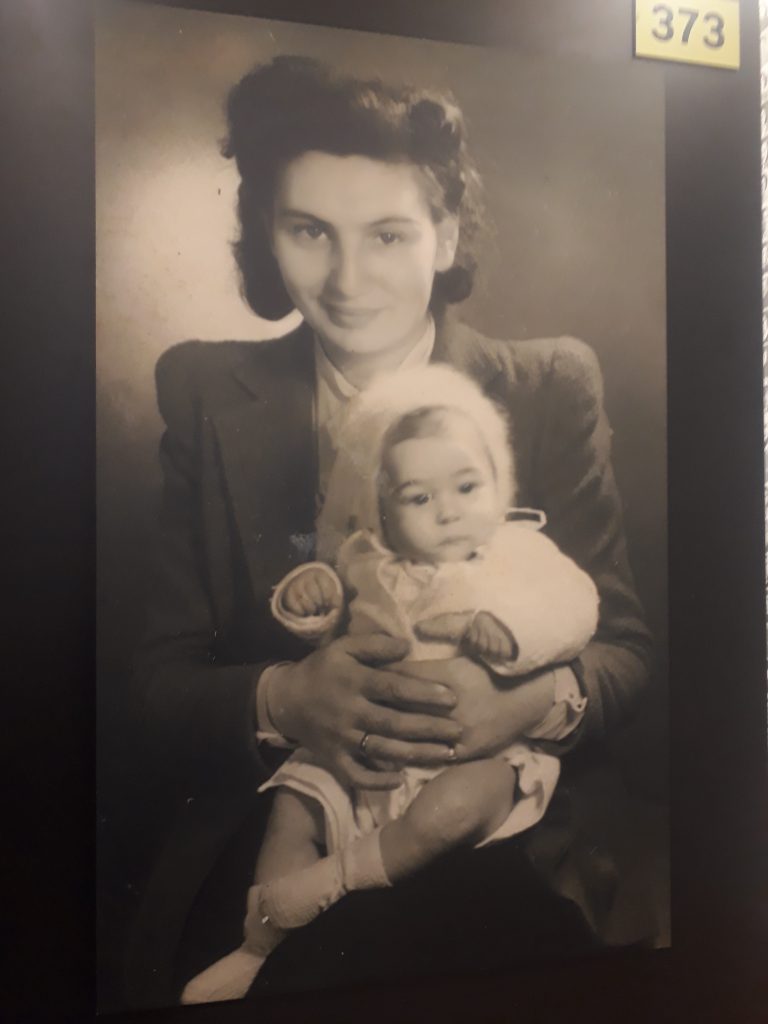

But also a note of hope, of revenge, on the death programmed by others, by the life chosen. That of the return to life of Malvine Löwenwirth, a survivor who got married in 1946 and this photo which concludes the exhibition where we see Malvine with her baby in her arms.

Mechelen is also a city known worldwide for its training in carillon music. People come from all over the world to study this in Mechelen. In Japan, the carillon is very popular. When Shinzo Abe, the Japanese Prime Minister, came to Belgium in 2018, he was accompanied by his wife Akie.

She chose what she wanted to visit: the carillon school, where a Japanese student was studying at the time, and the Kazerne Dossin, especially the part dedicated to children.

During her visit, Akie Abe asked specific questions, doing so with interest and not in a formal setting, demonstrating the importance of sharing memories and its surprising manifestations.

Article written by Steve Krief, with the precious help of Patsi Ambach, guide at the Kazerne Dossin museum