Visiting Budapest requires at least three days. The capital was born from the unification of three cities: Buda and Óbuda on the western shore of the Danube, and Pest on the eastern shores. Although wars and urbanization have left few traces of the Jewish presence in Buda, Pest contains an old Jewish quarter that still houses a portion of the community.

Buda

“There are a few Jews here and they speak French well; many were expelled from the kingdom of France”, Bertandon de la Brocquière noted in his 1433 Chronique de voyage à Boude (Chronicle of My Trip to Buda). The earliest arrival of Jews from Vienna certainly began as far back as the eleventh century. King Béla’s 1251 charter granted Jews the right to settle here, which offered them protection until the Ottoman era. Of the medieval period, only vestiges of a synagogue remain in the Baroque castle district. In the late fourteenth century, Jews built a large synagogue at 23 Táncsics Street, which was formerly called “Jewish Street”. The ruins here have yet to be restored.

Somewhat smaller, the synagogue at number 26 was a house of prayer, a temple serving the capital’s Sephardic community. Propped up by two Gothic pillars, the prayer room shelters two beautiful frescoes. One depicts a bow turned toward the sky, the other a star of David. The caption reads: “Powerful men equipped with bows were corrupt, while the weak were invested with power”.

The other Hebrew inscriptions, featuring Turkish stylizations, relay the fears of Sephardic Jews under Christian attack. Such fears were not unfounded: on one of the synagogue’s wall, the reproduction of a painting illustrates how the Jews of Buda were massacred in 1686 after the Turk’s defeat by the Austrians; they had been accused of collaborating with the Ottomans. Under Turkish occupation, Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jews had lived in harmony in Buda.

The Jews of Buda

“In the Jewish quarter of Buda one could buy almost everything: Persian carpets, kilim, velvet, muslin, fine linen, atlas, felt, aba cloth, frieze cloth, Moroccan leather. Fruits, even the most exotic ones that grew in the remotest corner of the Sultan’s empire, were sold there, as well as cattle, hide, flour, salt, timber. Credit was also available, against promissory notes. Jewish merchants played an important role in the ransoming of Christians who had been taken captive. Servants, too, were sold on the market.

Trade in wine, however, was prohibited even to the Jews. In order not to tempt the virtues of the Moslem population, the Turkish authorities forbade the use of wine, even in Jewish ceremonies.”

Géza Komoroczy, Ed., Jewish Budapest: Monuments, Rites, History (Budapest: Central European University Press, 1999).

Pest

Jews settled north of Pest’s current center, Deák Square, around a market where they sold grain, cattle, wool, and hides. In 1800, they numbered more than 1000 and soon built a synagogue in the Orczy House (destroyed) on the site of Madach square. Besides the synagogue, a rabbinical school was founded here, along with other school, baths, housing, and shops. Letter-writers rubbed elbows with matchmakers. The famous Café Orczy opened in 1825, where cantors were regularly recruited. Enriched by trade and industry, the nascent Jewish middle class soon wanted a temple worthy of its rank. The synagogue on Dohány Stret was opened in 1859, only a few years before the Jewish community gained full emancipation.

Here begins a tour of Pest’s Jewish quarter, delimited roughly by three synagogues that form a sort of triangle and represent the three branches of modern-day Judaism.

The assimilation of Hungarian Jews

Starting in the latter half of the nineteenth century, many Jews “Magyarized” their names.

“The teacher turns two pages. Maybe he has reach the letter K. Altmann who at the beginning of this term had his family name changed to the Hungarian Katona, now bitterly regrets this rash act.

Frigyes Karinthy, Please Sir!, Trans. Istán Farkas (Budapest: Corvina Press, 1968).

The synagogue on Dohány Street was designed by Austrian architect Ludwig Förster. Inspired by Vienna’s Tempelgasse synagogue and the Solomon Temple, Förster created an imposing structure, adding two towers to echo the columns of the Temple of Jerusalem. The outer, light-red brick walls are decorated with eastern and Byzantine-inspired motifs and are of a Moorish style very popular at the time. Förster’s work features a striking mix of Gerco-Roman, Roman, and Byzantine elements, integrating modern techniques: thin pillars of tempered steel support the upper galleries and roof, while the lighting comes from above.

Certain features are reminiscent of Christian church architecture. Unlike Orthodox synagogues, the bimah here is not found in the center but in the extension of the richly decorated aron, and it is modeled like an altar. A huge arch (40 feet in diameter) separates the sanctuary from the nave. One detail that scandalized Orthodox believers of the era was the presence of an organ, despite the traditional ban of musical instruments during Shabbat. The “Jewish Cathedral”, as some of its detractors have called it, symbolized the triumph of Neolog Jews, partisans of assimilation and modernization of Judaism. It is today the largest synagogue in Europe (254 ft. x 88 ft.) and served as the model for the one on East Fiftieth Street in New York City. Restored in the early 1990s by the Hungarian state, the synagogue can accomodate as many as 3,000 people. It is packed during major celebrations (Yom Kippur, Rosh Hashanah), were women can freely mingle with men.

The small adjacent museum has on display beautiful ritual objects, sacred decorations, and photos taken during the Shoah. Between the synagogue and museum, the remains of a redbrick wall signal the border of the ghetto built in late November 1944 and liberated by the Soviets on 18 January 1945. Through the arcades of the courtyard, the mass graves of Jews who died in the ghetto can be seen. Here also stands the Temple of Heroes: built in 1929 as a memorial to soldiers fallen during the First World War, it serves today as an everyday house of worship.

Behind the synagogue, a Shoah memorial stands in the middle of an open courtyard. The work of sculptor Imre Varga (1990), this steel and granite weeping willow is in fact an inverse menorah. The black marble arch symbolizes the Ark of the Law, hollowed out by the annihilation of the Shoah. The park is dedicated to Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who saved thousands of Jews during the war. Saving Angel, an ormulu sculpture on Dob Street, has been erected in honor of another righteous soul, Swiss consul carl Lutz.

The synagogue on Rumbach Street , a major work by Austrian architect Otto Wagner, was built in 1872 for the traditionalists who refused to take sides on the dispute between Neologs and Orthodox Jews. In Romantic-Moorish style, the building’s exterior is decorated with numerous Arab-inspired motifs and two turrets shaped like minarets. The synagogue was given back to the Jewish community by the Hungarian government in 2006, the authorities helping the much needed restoration. It reopened as a polyvalent Jewish cultural center in 2020.

The Orthodox synagogue is pure Art Nouveau, built in 1913 according to plans by the Löffler brothers. Severely damaged during the war, it has been almost entirely restored to its original state. The superb ceiling is decorated with eastern-inspired floral motifs, palms, and lotus flowers typical of late Jugendstil. The stained-glass windows, in a ring, diffuse an optimal light, while very stylized menorot decorate the galleries, banisters, and windows. The gilded marble aron is the work of Italian masters. In the courtyard, you will notice the huppah, a dais of forged iron under which Orthodox Ashkenazic Jews celebrate outdoor marriages. The courtyard also houses a small prayer room (only holidays are celebrated in the synagogue), a kosher dining hall, a yeshiva, and a butcher shop.

The only functioning mikvah is Hungary is located at 16 Kacinczy Street. At number 41 (in the courtyard), the kosher delicatessen Dezsö Kövari seems taken right out of a film from the 1930s. The proprietress stands stone-faced behind her counter, on which an immense red slicer holds the place of honor.

A stroll through the somber streets with their peeling facades hints at the splendors of times past. The door of 16 Sip Street is shaped like a menorah, while that of number 17 hides a stylized tree of life. The Neolog community’s headquarters are located at 12 Sip Street. The cultural center itself is found near the opera.

A required stopping place for a bite to eat used to be the Fröhlich Bakery , where you were able to sample exquisite Kindli and Flodni, Purim cakes made with poppy seeds and nuts. It has closed after the Covid. Taking Dob Street up to Klauzál Square, you will find Kadar restaurant , a cult hangout. A Yiddish proverb maintains that “it takes two to eat a chicken: me…and the chicken”.

This is exactly the ambience that prevails in this cramped bistro where you will have to share your table with the regulars. On the wall hang photographs f famous actors, most notably of Marcello Mastroianni, who stopped here for a hearty meal. Students and artists come to savor, at ridiculously low prices, Jewish cuisine…Hungarian style. While they do serve a copious cholent here, a shabbat dish made from red beans, there is nothing kosher about it. They serve the dish on Fridays and Saturdays, embellishing it with bacon or smoked breast; it is also offered with roasted goose or chicken. On the menu, other Jewish specialities -boiled beef with cherries- line up alongside undeniably Magyar paprika stews. Kadar is a temple of gastronomic assimilation.

The history of Cholent, traditional shabbat dish

“[a dish of] Central European Jewry, the best, the most satisfying: made especially for the poor, who could keep it in their kitchens for three or four days, or even longer, without fear if its going bad.

It was a concoction of dried beans, eggs, rice and goose-flesh (sometimes beef or lamb instead), and was cooked in the oven in a big saucepan, its lid fastened wit fine string to which was fastened a label bearing the name of the family who owned it. This was because the sciolet needed a whole night’s cooking and was therefore placed in the big communal oven. No private house could burn and keep watch over a fire for that length of time.

Giorgio and Nicola Pressburger, Homage to the Eight District: Tales from Budapest, Trans. Gerald Moore (London: Readers International, 1990).

Not far from the Jewish quarter, Andrássy Street is worth a stroll for its splendid mansions, two-third of which were inhabited by Jewish families at the turn of the twentieth century. At number 23 lived the banker Mor Wahrmann: a rabbi’s grandson, he became president of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and the first Jewish deputy elected to Parliament in 1869. He advocated emancipation, but for the leisure class alone.

In the footsteps of Jewish artists

Throughout the city, Jewish artists have left their mark. We should not overlook Miksa Róth , who designed the stained-glass windows for innumerable buildings, including the Gresham Palace, the magnificent Franz Liszt Music Academy, and the Museum of Agriculture.

The architect Béla Lajta cleverly blended Art Nouveau, Jewish motifs, and Hungarian folk style in his buildings: gates were often adorned with menorot, six-pointed stars, and biblical motifs like the tree and the serpent, or Noah’s Ark. The staircases he designed for the Institute for Neurological Research (founded in 1911) resemble towers. At the top, a complex structure of wooden beams is reminiscent of Transylvanian architecture. The Institute for Handicapped Children and the hospital on Amérikai Street are two other remarkable examples.

Latja also designed several mausoleums for the Rákoskersztúr cemetery . The mausoleum of the Schmidl family, for example, is impressive; its decor -majolica and mosaics made of glass and marble -was inspired by the sepulcher of Galla Placidia in Ravenna.

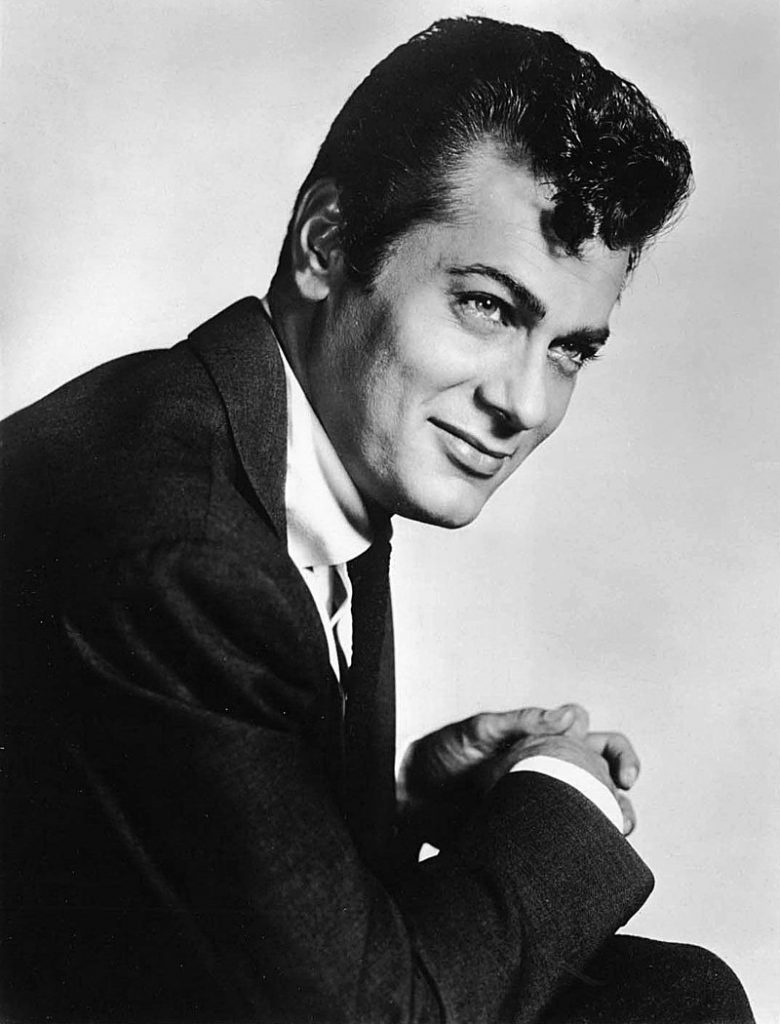

Tony Curtis

Bernard Schwartz, better known as Tony Curtis, financed the reconstruction of Jewish life in Budapest with Estée Lauder and the Hungarian government when democracy returned in the 1990s.

Emmanuel Schwartz, the tailor father of the great actor of Defiant Ones, Some Like It Hot and Spartacus, was born in Mateszalka in Hungary. His mother, Hélène Klein, was born in Slovakia. They started a family in New York, where Tony was born. They lived in great poverty there, and were also subjected to anti-Semitism. In 1984, Tony Curtis recounted in a BBC documentary how his father felt he had escaped his difficult circumstances by going into a synagogue on feast days, his son looking at him with emotion.

After a difficult childhood, he joined the navy in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor. After the war, he studied theatre in New York and began his magnificent career with Universal. Reconnecting with his origins, he took part in tourism promotions in Hungary and financed the restoration of the Dohany synagogue. A year after his death, in 2021, his daughter, Jamie Lee Curtis, financed the restoration of the Mátészalka synagogue. The city has opened a Tony Curtis museum and is organising the Tony Curtis International Film Festival from 19 to 21 September, with the aim of encouraging collaboration between Hungarian and international artists.