Although there was an organized community in Tomar at the turn of the fourteenth century, indicated by the inscription on the tombstone of Rabbi Joseph of Tomar, who died in Faro in 1315, it was not until 1430 that the Jews of Tomar had the means to undertake the construction of the synagogue. A building that still stands today. It was completed in 1460.

After the expulsion of 1496, the synagogue was converted to a prison, then used by successive owners as a hay barn. In 1920, a group of Portuguese archaeologists identified the building as a synagogue.

It was placed on the historical register in 1921. In 1923, the engineer Samuel Schwarz, who worked in the region’s mines, heard about the building and bought it. In 1939, after carrying out initial restoration work, he donated it to the state with the provision that it set up a Portuguese-Jewish museum there.

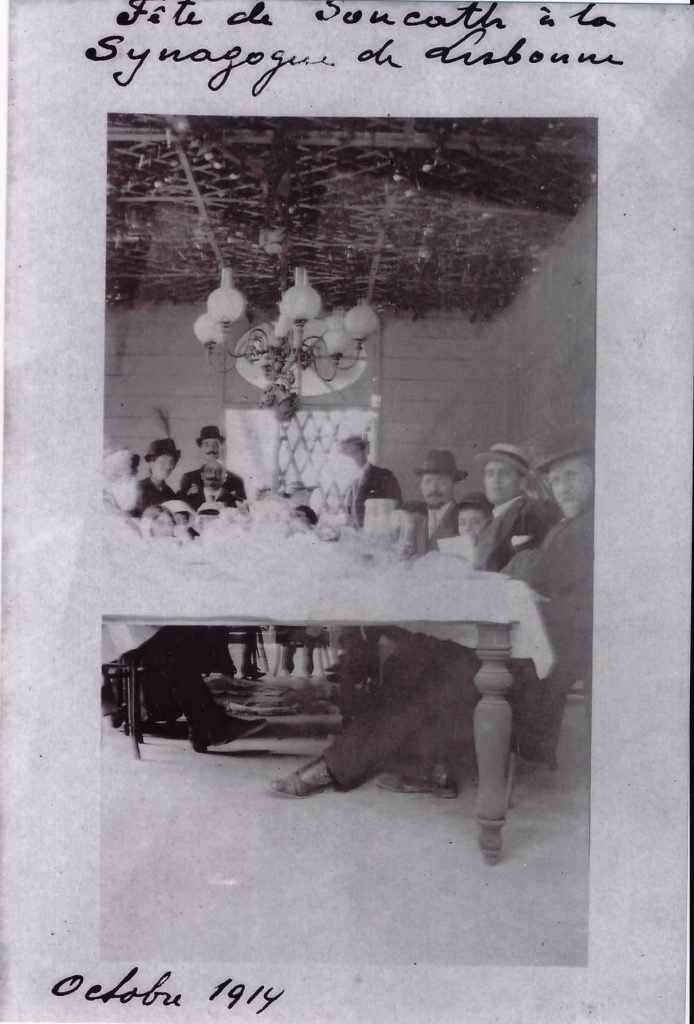

The synagogue is supported by four fine columns at the center, reminiscent of these in the Portuguese church at Ourem made by Hispano-Moorish craftsmen. Indeed, the same builders could well have been involved here. Recent excavation has revealed parts of the mikveh. Several coins from the age of King Alfonso V (1446-81) and everyday tableware have also been found.

The facade and entrance are modest and unremarkable. Upon entering, several steps lead down to the floor, which, below street level, made it possible to reduce the height of the facade.

Inside the synagogue is the Abraham Zacuto Museum, named in honour of the mathematician and author of the perpetual almanac (1450-1522). The permanent exhibition includes archaeological finds that attest to the Jewish presence in Portugal in the Middle Ages. There is a 1307 inscription from the old Lisbon synagogue. Another, dating from the 13th century and found in Belmonte, is just as interesting: the divine name is represented by three dots, in the manner of the Dead Sea Scrolls.

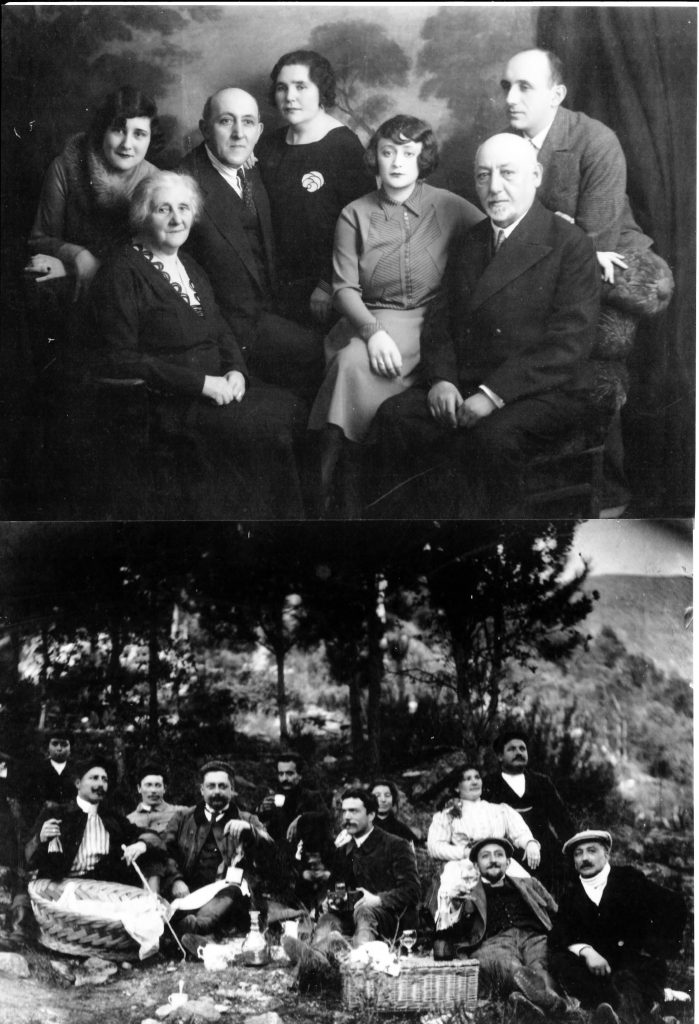

In 1917, during a mission in the north of Portugal, mining engineer Samuel Schwarz discovered the Marranos of Belmonte. Thanks to a multidisciplinary approach, his book, published in 1925, became an absolute study on the Marrano phenomenon and, above all, enabled the rebirth of Jewish life in the region.

The book gained a new popularity thanks to its publishing by the French editors Chandeigne. Here’s our interview with his grandson, Joao Schwarz.

Jguideeurope: How did Samuel Schwarz come up with the idea of translating his experience into a book?

Joao Schwarz: During his stay in Spain in 1908 and 1909, he already wrote his first articles on the Marranos (in French). With the father he had and the cultural tradition that prevailed at his home in Poland, it was natural for him to publish the results of his research. We need to add that during the era of 1919-1926, the Republic of Portugal enjoyed a certain form of freedom. The situation changed with the Estado Novo which, among other things, opened the gates of anti-Semitism and put back on track a much more asserted clericalism.

Why did it take 8 years to be published? And how was it perceived once it was done?

Since the beginning of his research and until the publishing of the book, it indeed took 8 years. Nevertheless, the census process and the inventory of the Marrano prayers lasted almost until 1924. During that time, he worked on the book about the Hebraic inscriptions in Portugal, which was published in 1923. That being said, the publishing of the text in Portuguese was accompanied by the printing of articles in the Jewish press.

Reviewing the debates of that era, we can claim that the articles and the book had a considerable effect in the Jewish world. That’s why Lucien Wolf and Paul Goodman, among others, were sent to Portugal in order to inquire upon that phenomenon. In Portugal, it was the beginning of a renaissance of Jewishness, with a lot of people from the region of Tras-os-Montes identifying with it.

Samuel was invited to blossoming reunions. That’s also where the rescue work started under the leadership of Capitain Barros Basto.

What is the impact of Samuel Schwarz’s commitment on the research concerning the Marranos and the national (re)discovery of the Jewish heritage?

I believe that the impact on research was decisive. Nevertheless, we had to wait until the middle of the 1980s to find a number of works that highlighted the rebirth of Jewishness in the region. Historians such as Anita Novinski, David Canelo, Maria Antonieta Garcia etc… Concerning the rediscovery of Jewish heritage, it’s another question. Indeed, an effort aimed at this heritage, through its preservation and valorization was only undertaken in the last fifteen years. Notably since the creation of the Rede de Judiarias of Portugal. We must also mention that the granting of Portuguese nationality to the descendants of Jews from that country contributed a lot, especially in those last years, to attract visitors interested by their roots. About 30,000 new Portuguese citizens settled in the country, particularly in the North.

Samuel Schwarz gave a plot to the city of Tomar in exchange for the building of a Jewish Museum on it. A museum which opened in 1939. Quite a rare event on the continent that year. What was displayed in it?

Samuel bought a building in 1923, which at that time was a sort of grocery warehouse. This building was already recognized as a national monument, without anything being done to preserve it. Samuel undertook cleaning works in order to reveal to the country what today represents the oldest Portuguese synagogue still standing. The oldest publishing on that temple (1925) was from Garcês Teixeira, an archeologist who shared the first elements of what was the Jewish community of Tomar towards the end of the 15th century. It must be noted that the annex building of the synagogue, which runs along the mikveh, was only discovered in the 1980s. After considerable works of restoration, which took a lot of time considering the means at Samuel Schwarz’s disposal, it was decided to donate it to the Portuguese State. On the sole condition that the “Museu Luso-Hebraico Abraão Zacuto” would be built on it. The place where the synagogue stands included at that time a few headstones and tombstones mentioning the Jewish past of Portugal. In return for this gift, the Portuguese government agreed to Samuel’s request and granted him the Portuguese nationality.

The introduction of the book by Livia Parnes describes the way the authorities “forgot” the museum’s vocation for many years. How is Tomar sharing that heritage today?

Indeed, the building was “forgotten” for many long years, due to reasons of administrative mastery. The synagogue doors were only opened thanks to the goodwill of the couple Luis and Teresa Vasco who, in all seasons, ensured its permanent opening. This is how the number of visitors was able to remain stable and to attain almost 100,000 a year in 2015. The municipal authorities, due to a lack of means, ignored the existence of the synagogue for almost 80 years. The deal changed with the creation of the Rede de Judiarias. The municipality was able to “refurbish” the synagogue and the adjoining space where the mikveh is located. Nevertheless, I think that in order to preserve and support this heritage, a sustained effort is necessary and not in fits and starts, as was the case until today. This supposes that the museum gets equipped with a person in charge of the resources.

Samuel Schwarz, La Découverte des marranes. Editions Chandeigne, Paris 2015.