Alytus is a town on the river Nemunas, crossed by the main roads linking the country’s major cities.

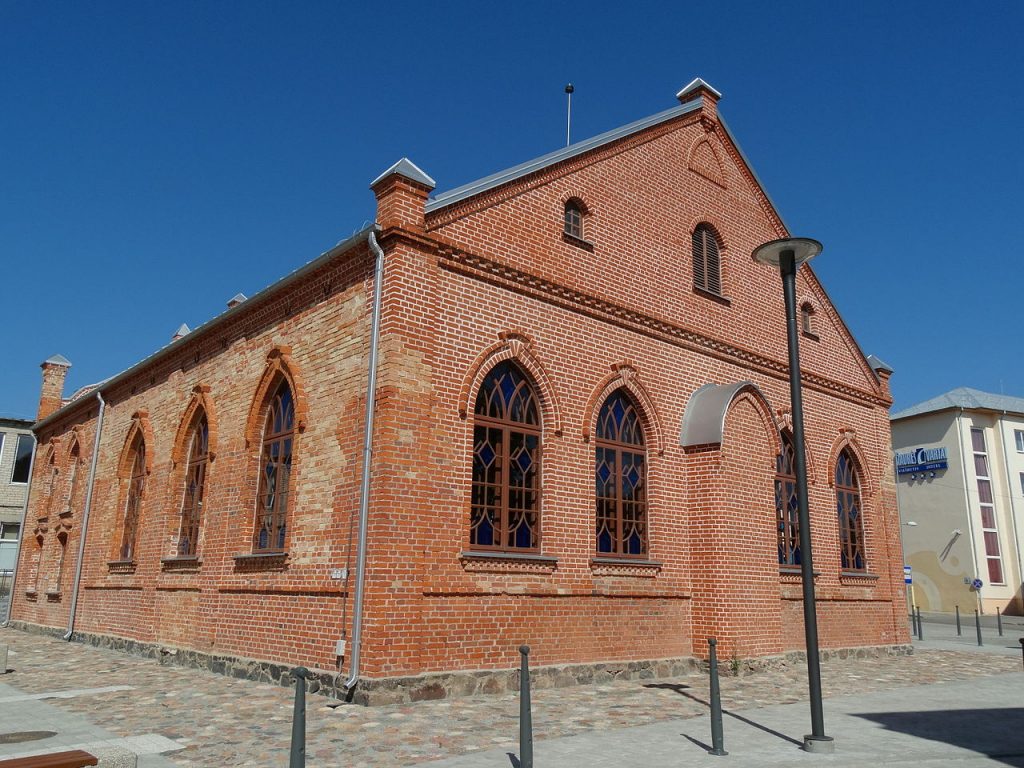

Today, there are few traces left of Jewish life in Alytus. The synagogue , built with yellow and red bricks, dates from 1911. The choice of bricks, which differ from the country’s wooden synagogues, was made following a fire that destroyed the town’s wooden synagogue some time earlier.

During the Soviet era, the building was used as a warehouse and then abandoned. Some of the interior decorations have survived the passage of time. Plans are underway to restore it and turn it into a cultural centre. There is also a Jewish cemetery in the town.

The town of Joniskis is quite old, dating back to the 16th century. The Jewish presence in Joniskis dates back to the 18th century. They lived mainly around the main synagogues.

Before the Shoah, the town’s Jewish population represented almost half of its inhabitants. The vast majority were massacred, as in the rest of the country. There are no Jews left in Joniskis today, but the small community of Siauliai took part in the re-inauguration of its synagogues.

Two synagogues dating from the 19th century stand side by side in the centre of the town, named for their colour. The white synagogue was built in 1823. It also served as a Jewish school. The red synagogue was built in 1865. During the Soviet era, it was transformed into a residential and youth centre.

The complex formed by the two synagogues was placed under the patronage of the Lithuanian Ministry of Culture in 1970. Restoration was undertaken following the country’s independence at the end of the 1990s.

Severely damaged by storms in 2004 and 2007, the destroyed walls were rebuilt with the help of European institutions and Norway, in partnership with the local authorities.

Since 2014, the red synagogue has been used as a cultural centre. The white synagogue also benefited from European aid to be restored in 2017.

Sources : JTA

The town of Kedainiai dates back to the 14th century, making it one of the oldest in the country. Under the Kishkis family, who ruled the town from 1490, Jewish merchants were invited to settle. The city became a Calvinist centre in the mid-16th century, and Jews were granted civil rights and freedom of worship. They worked in a wide range of sectors, reflecting this successful integration: import-export, trade, crafts, agriculture, etc.

In 1766, 500 Jewish families were registered in Kedainiai, which became a major place of learning at the time. But when the region came under Russian administration, the Jews lost many of their rights. From the middle of the 19th century, the Jewish population declined from almost 5,000 in 1847 to 3,733 in 1897, mainly as a result of waves of migration at the end of that century.

Expelled by the Russian authorities to the interior of the country during the First World War, the Jews subsequently resettled here. They then worked mainly in agriculture, making up 2,500 inhabitants in 1923.

In 1939, Kedainiai took in refugees from Poland fleeing Nazism. Most of the Jews present in the town during the Holocaust were massacred by the Nazis with the help of local militias.

Today, two synagogues remain in Kedainiai, one opposite the other. They were used as warehouses after the war and were restored at the beginning of the 21st century, now forming a cultural complex. The smaller of the two, the Winter Synagogue, was built in 1837.

A permanent exhibition in the former women’s section traces the city’s Jewish history, showing the community’s former sites and commemorating the victims of the Shoah. The summer synagogue is older, dating back to 1784. An ancient Jewish cemetery and a more recent Jewish cemetery are located close to the town. A monument has been erected in the forest on the road to Dotnuva, where many Jews were massacred during the Shoah.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

The town of Pakruojis is situated on the river Kruoja and was founded in the 15th century. The wooden synagogue dating from 1801 is probably the oldest of its kind in the country. Between the wars, the building was used as both a synagogue and a primary school.

The Jewish population was massacred during the Holocaust. After the war, the building was converted into a cinema and then abandoned. A fire heavily damaged the building in 2009, prompting a fundraising campaign to restore the site. This was undertaken in 2015, with the help of old photos of the synagogue . And thanks to the local authorities and the help of other European countries, mainly Norway.

Following the restoration, the building housing the former synagogue was reopened in May 2017. Since then, it has been used as a venue for the daughter’s public bookshop, as well as hosting cultural events. A permanent exhibition upstairs, where women used to pray, gives visitors an insight into the history of the Jews of the Pakruojis region. A Jewish cemetery is located outside the town on the road to Linkmuciai and was restored in 2011.

Urla is located 25 miles from Izmir. It is assumed that the town’s Jewish community originated on the Aegean islands of Mora and Izmir.

In 1840, Urla’s Jewish community numbered 40 families, rising to 90 by 1900. At the end of the Turkish War of Independence, the Greeks, forced to leave Urla, set fire to the town, thus displacing the majority of the Jews.

The community emigrated to Izmir, Rhodes and the United States. Today, on the site of the old Jewish quarter, on the corner of The Victory Victoire and the Post Office streets, stands a building that was probably once a synagogue. The tombstone of Isak Eskenazi, a leading figure in the town, is preserved by the local council.

The Eskenazi house has been restored and now houses the town hall. The Arditi Pavillon is located in the Turkish quarter of Urla. Built in the mid-19th century, the pavilion was used as a home until the 1930s. Now owned by the Town Hall, it was also used as a courthouse. The pavilion can be seen on Urla Park street, opposite the Hocaali mosque.

Strategically located on the trade route between Sardis and Izmir, Turgutlu was home to a large Jewish community. Gravestones with Hebrew inscriptions dating back to 1391 have been found here.

In the 19th century, there were three synagogues in Turgutlu. They were destroyed in the fire that ravaged the town in 1922. The synagogue that can be seen today dates from 1939, but is unoccupied due to the lack of a community.

The last Jews left the town for Izmir in 1967. The Turgutlu museum has an exhibition room devoted to the town’s non-Muslim minorities (Roma, Armenians and Jews).

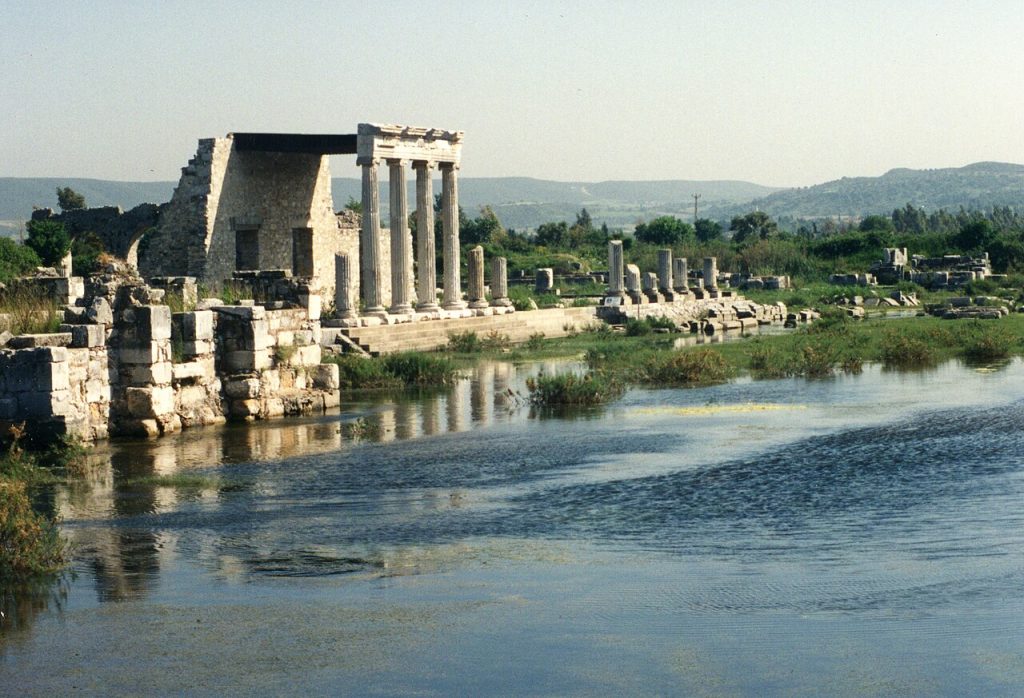

Compared with other cities, Priene was a modest town whose economic growth was always hindered by Miletus. During excavations carried out between 1895 and 1898, German archaeologists discovered the town’s synagogue (originally mistakenly described as a church).

The wall faces Jerusalem and features a niche for the Torah and a marble basin. Three engravings depict citron, menorot, and shofarim. The decoration suggests that the structure dates from the Byzantine period.

Tombstones with Hebrew inscriptions dating back to 1271 have been found in Tire’s old Jewish cemetery.

The town’s hamam, which dates back to the 16th century, also houses a mikveh that was certainly built at the same time.

The Jewish quarter and its three synagogues burned down in 1917. Only the Kahal Shalom synagogue was rebuilt. It is no longer used as a place of worship, and its building has been converted into a shop.

While the town’s two former Jewish cemeteries have been closed, the modern cemetery, which dates from the 1960s, contains around 120 graves.

In Hellenistic times, Sardis was home to one of the largest synagogues in the world. It was discovered by American archaeologists in 1960. It was completely destroyed by an earthquake in 17 AD.

Pergamon is one of the thirty districts of the province of Izmir. The city lies 93 kilometres north of Izmir. What is now known as Bergama was built on the remains of the ancient city of Pergamon. A Jewish community is known to have lived in Elaea, which was the port of Pergamum in Roman times and, from the second century BC, in the city centre itself.

In Ottoman times, the Jewish residential quarter was located opposite the Kinik terminal, from the Yabets synagogue along Üçkemer Avenue. The Jews of Pergamon had two synagogues, Yabets and the second located on the Kinik terminal itself. The latter dates back to 1862 and was built on the ruins of Pergamon’s oldest synagogue. The building was restored in 1896 after being damaged in an earthquake. From 1898, the Alliance Universelle school moved into the synagogue courtyard. Under the Turkish Republic, the synagogue and its school were demolished to build the terminal we know today. All that remains of what was once a place of worship is a visible wall.

The Yabets synagogue was built in 1875 by Ephraim Bengiat. Gradually abandoned following the mass emigration of the community to Israel from 1948 onwards, the synagogue was used as a hangar. In 2000, a fire severely damaged the building, and restoration work began in 2010. The synagogue was re-inaugurated on 11 May 2014. It now houses an exhibition hall and cultural activities.

Finally, the Red Basilica, located opposite the Kinik terminal, displays the tombstones found in the Jewish cemetery of Pergamon.

Inscriptions found in the theater of Miletus give some indication of a Jewish presence.

Dating from the 2nd or 3rd century AD, these engravings read “the place of the monotheistic Jews” or “the place of the blue Jews”. Blue and green were the colours of the chariot racing teams. Belonging to these teams was a great privilege and proved that the community was well integrated into the city.

Manisa is 125 kilometres from Izmir. On the wall of a house in the Ayvazpasa district, you can read the following inscription: “Starton, the son of the Jew Tyrannos had this tomb built for his wife, his children and himself”. This tombstone dates from the Roman period, between the 2nd and 4th centuries.

From that time until the Ottoman period, there was no evidence of a Jewish community in Manisa. This was the case until 1492, when a number of Jews fleeing Spain took refuge in Manisa. There were 500 Jews in 1531 and 800 in 1575. In 1599, Rabbi Menahem Ben Elyezer, who had come to Izmir from Safed, documented the presence of a Jewish community in Manisa in his book Shir HaShirim. Today, there are no longer any Jews in Manisa. However, they have left valuable historical traces.

There were two Jewish cemeteries in Manisa, which disappeared during the urbanisation of the city. The Jewish cemetery next to the Alaybey mosque (Dilsikar Hatun) was transferred to the Muslim cemetery to the east of the city. The lack of maintenance of the tombs has made the inscriptions illegible. The oldest tomb belongs to Yosef Bueno Bira and dates from 18 adar 5683 (18 March 1933). The most recent tomb belongs to Davi Süzen and dates from 17 February 1950.

Three mosaics from the Sardis synagogue are on display in the Manisa museum . The museum’s garden contains tombstones from the town’s former Jewish cemeteries.

The town’s paediatric hospital was funded by Moris Sinasi and opened in 1933.

Located within the boundaries of the Selçuk district, Ephesus was one of the most important cities in Ionia during the Roman Empire and the Classical period. The ancient city is famous for the remains that have been found there: the Cathedral of Mary, the Church of St John, the Celsius Library, the Temple of Artemis, etc.

During the Roman era, Ephesus had a large Jewish population, and was one of the first communities visited by Saint Paul. An engraved menorah has been found on the stairs of the Celsius Library , and another on one of the columns of the Avenue du Port, as well as at the entrance to the Agora.

During archaeological excavations in Aphrodisias, an ancient city listed as a UNESCO World Heritage Site, numerous inscriptions referring to a Jewish community were discovered.

On three marble slabs, representations of menorot, citron trees, palm branches, and shofarim were found. In the covered theatre of the Odeion, on one of the bleachers, is engraved “The place of the ancient Jews”.

An inscription discovered in the town and now on display in the Museum of Aphrodisias bears the names of the town’s 16 Jewish families. This plaque, which was probably used for administrative census purposes, dates back to the 3rd century AD.

A Jewish community existed in Akhisar during the Hellenistic period. In 1904, the town still had 75 families and a synagogue, of which nothing remains today. After liberation from Greek occupation in 1922, most of Akhisar’s Jews emigrated to Izmir.

The Akhisar Jewish cemetery is to the south of the town, next to the Resat Bey cemetery. There are around one hundred graves here.

An agricultural colony, dating from 1899, is located near Akhisar. Founded by the Association Israélite Universelle and the Jewish Colonisation Organisation, it was intended to enable Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe to learn the rudiments of agricultural work in order to secure their livelihood as quickly as possible.

The Jewish community of Baza dates back to the 11th century. The inhabitants of the judería were few in number but prospered thanks to the silk trade. A mikveh has been discovered here, an excellent example of 11th-century Arabic architecture. Nothing remains of the old Jewish quarter, which spread out around the mikveh in Place de Santiago.

Auschwitz remains the most terrible symbol of the Shoah, a symbol that is periodically threatened with being either denied or reclaimed. Since 2005, however, the Museum’s curators have done an outstanding job in putting together a new permanent exhibition, in addition to the one that has existed since 1947.

A visit is therefore a must for anyone who has any doubts about the reality of the Final Solution, or who still imagines that it could be a mere “detail” of the Second World War. Over 800,000, perhaps more than a million victims, perished at Auschwitz.

The tour includes both camps: the central Auschwitz camp (Oswiecim) and the Birkenau camp (Brzezinka), where the gas chambers were located. Although the visit is trying and exhausting, you absolutely must see both camps.

It is advisable to visit Auschwitz during the day, for example from Krakow, without spending the night in this place of absolute horror. Allow four or five hours for your visit. Given the number of tourists, it is advisable to visit the site either in the early morning or at the end of the day. With 2 million visitors a year, the place of remembrance has become almost impossible to visit. For those who would like to reflect in an atmosphere more appropriate to the attitude to be adopted in this kind of place, it is advisable to visit less frequented camps, such as Sobibor, for example.

The museum, located on the site of the former camp, was created thanks to the efforts of former prisoners from 1947 onwards, and has added new wings since 2005. Its aim is to safeguard the remains of the former camp, commemorate the victims and pursue scientific and educational activities.

The place of remembrance covers an area of almost 200 hectares, with more than 150 buildings and around 300 ruins, including the remains of the gas chambers and crematoria that the Germans destroyed. It is also a research centre for documents, archives, and the world’s largest collection of works of art dedicated to Auschwitz – around 6,000 works.

In 1979, on Poland’s initiative, Auschwitz was inscribed on UNESCO’s World Heritage List, emphasising that it would be the only ex-camp on this list and that it would be the symbol of all other similar places.

The Museum’s educational mission is carried out by the International Centre for Education about Auschwitz and the Holocaust. The Centre’s main activity consists of educational programmes which, based on the history and experiences of Auschwitz, aim to raise public awareness and foster a responsible attitude in the world today.

In the second quarter of 1942, the Germans began liquidating the Polish ghettos. According to the process put in place by the Occupier, the Jews of the village of Markowa, near Lancut, and those of the surrounding villages, were first sent to the Pelkiny camp, then to the Belzec death camp. Anticipating the worst in the face of this growing terror, many Jews went into hiding. The Germans regularly organised searches for fugitives. Those captured were usually shot in the village where they had taken refuge.

After sheltering 8 Jews from Lancut and Markowa under their roof, the Ulma family suffered the same tragic fate as Poles who sheltered Jews. On 24 March 1944, following their denunciation by a policeman from Lancut, the Jews sheltered by Jozef and Wiktoria Ulma, themselves and their 6 children, aged between 8 years and 18 months, were shot by the Germans. More than 20 other Jews remained in hiding in Markowa until the end of the war.

Today, the museum named after the Ulma family carries out cultural activities, studies, and documentation work, as well as educational activities. The cultural programme includes exhibitions, concerts, film screenings, meetings, and other initiatives. The museum organises commemorations dedicated to the Ulma family and other Poles who saved Jews, as well as to the fate of persecuted Jews. Documentation and scientific studies consist of collecting and studying sources relating to Polish aid to the Jewish population. Witness accounts and documents are constantly coming into the museum, and the permanent collection is constantly being enriched.

The Polish prime minister, Mateusz Morawiecki, visited the museum in 2018 and took part in a ceremony in tribute to this courageous family.

Seduva is a town formerly known for its agricultural production. The Jewish presence in Seduva appears to be quite ancient, dating back at least to the 15th century.

At the end of the 18th century, there were around 500 Jewish families. A hundred years later, they made up 56% of the total population. This number declined in the early 20th century. The town had a yeshiva and a Jewish school.

Jewish social and cultural activities suffered under the Soviet occupation in 1940. A year later, many Jews were arrested and transported by German troops, aided by local nationalists, to Pavartyciai, a village five kilometres away. There they were crammed into barracks and shot, while others were murdered in Liaudiskiai. The town of Seduva was liberated in 1944.

As part of the reparation process, the Jewish cemetery was restored in 2013, with the oldest tomb dating back to 1782, and memorials were inaugurated at the sites of the massacres, in Pavartyciai and Liaudiskiai .

These restoration efforts have given rise to an original initiative, due to be completed in 2025. This is the Lost Shtetl , designed by Sergey Kanovich. The project was inspired by the many stories about the Jews of Seduva. It is gradually taking shape, thanks to the help of architects who worked on the design of the POLIN museum. The aim of the museum is to present the Jewish history of Seduva and all its cultural, religious, folkloric and societal aspects within the shtetl and in its interactions with the town’s population.

The museum’s website already features many informative and entertaining accounts of life in the past, from winter sports and a local pilot who crossed the Atlantic in 1935 to the moving story of Khana Muzikant, a widow who lost a son in the Lithuanian liberation struggle and who worked hard in the 1920s to save several of her children by organising their departure.

Sources : Yad Vashem, lostshtetl.lt

The town, capital of the region of the same name, enjoyed rapid prosperity in the 1800s thanks to its geographical location. Railways and companies were built relatively early on. Jews worked in various economic sectors, notably as tanners, in the metal industry, and in various forms of craftsmanship.

The Jewish presence in the town of Siauliai probably dates back to the 17th century. They obtained permission to build a synagogue as early as 1701. Social and cultural life was also quite varied. There were around fifteen synagogues and several Jewish schools.

The Jewish population of Siauliai was almost 10,000 in 1902, which represented three-quarters of the general population. In 1915, many Jews were expelled to inland Russia. Siauliai was one of Lithuania’s main cities at the turn of the 20th century.

Before the German invasion, a few hundred Jews managed to flee to Russia. Of those who remained, thousands were murdered by the Germans and their local henchmen. As is often the case in the region, there were few survivors of the Shoah. A memorial has been created.

After the war, the Jewish community was gradually rebuilt. There were 4,000 Jews in Siauliai in 1960. This figure declined during the Soviet occupation and following Lithuania’s independence. The old house, built in 1908 in the Art Nouveau style and owned by Jewish merchants, the Frenkelis family, now serves as a Jewish museum of local Jewish life.

In 2021, a project to build a cycle path next to a Holocaust victims’ grave was suspended following complaints. The town also has an ancient Jewish cemetery .

Sources, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Times of Israel

Tirksliai is a small town in northern Lithuania. The Jewish presence in Tirksliai probably dates back to the 18th century. Like most other regional religious establishments, the community built a wooden synagogue in the 19th century, which housed numerous manuscripts in Hebrew and Yiddish. It had several entrances, probably to allow separate entrances for men and women.

The Jewish community was decimated during the Shoah. The synagogue was first used as a warehouse by the Soviets, and was restored following Lithuania’s independence.

Ziezmariai lies at the crossroads of the road between Vilnius and Kaunas, and was often crossed and attacked by troops during regional conflicts.

The Jewish presence in the town of Ziesmariai probably dates back to the 16th century. Jewish life gradually took shape, with the opening of Jewish schools and venues for social and cultural activities, including sport and theatre.

A wooden synagogue was built in the mid-19th century. Badly damaged by fire, it was rebuilt each time. Following Lithuania’s independence, a restoration project was undertaken in 2017. A museum project on local Jewish history is currently being studied.

Rezekne is built on seven hills, giving it its name. The Jewish presence in Rezekne probably dates back to the 18th century. The town’s Jewish population grew mainly in the second half of the 19th century, from 542 in 1847 to almost 6,500 in 1897. Most Jews worked as craftsmen and tradesmen. Their participation in the life of the city was facilitated between the wars. The community benefited from a yeshiva and Jewish schools.

Following the German invasion in 1941, most of the remaining Jews were exterminated. Jewish life resumed very timidly after the war, not least because of Soviet restrictions. Only one of the eleven synagogues was still in use. Built of wood, as was often the case in the country, it dates back to 1845. The synagogue was restored in 2016, and cultural events have been held there ever since. The Jewish population was estimated at 250 in 1970, declining to 40 by 2025.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Ludza is famous for its ancient castle. The Jewish presence in Ludza probably dates back to the 16th century, but continued from the 18th century onwards. At the turn of the 19th century, there were 582 Jews in Ludza. By the end of the century, there were 2,803. Their main activities at the time were as tailors and craftsmen. But they were also involved in the grain trade, timber, and other agricultural products.

Ludza was famous for its eminent rabbis and scholars, mainly from the Zioni family. Most children studied in local Jewish schools. There were eight wooden synagogues in the town in 1937. Among them was probably the oldest in Latvia, built around 1800 and surviving the huge fire of 1938. This synagogue was used after the war by the few Jews who returned and restored in 2016.

During the German occupation in 1941, the Jews were forced to live in a ghetto. The vast majority were massacred during the Holocaust.

The Ludza synagogue, named a national monument in 2013, has recently been transformed into a museum following restoration work. It presents the history of the local Jewish community over the centuries.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

The City of the Dukes is the historic capital of the States of Savoy.

The Jewish presence in Chambéry probably dates back to the 14th century, following Count Edward’s call for their settlement in 1319. Most families lived on rue de la Juiverie, now rue de la Trésorerie . This street faced a two-storey tower attached to the castle.

They often worked as bankers and pawnbrokers, both because the Church forbade Christians to practice this profession, and because local authorities in much of Europe restricted or forbade Jews’ access to other trades. In Savoy, they also practiced two other trades: that of ragpicker and above all that of physician, notably for the princes of Savoy.

Despite relatively good autonomy at the time, this did not prevent many Jews from being murdered during the Great Plague in the 14th century, accused of having spread the disease. After a period of calm, the Jews were persecuted again in 1466. This led to the departure of most of Savoy’s Jews for Italy.

Although the French Revolution brought Jews back to France, the Jewish population of Savoie increased mainly as a result of the 1870 war. As a result, many Jews from Alsace-Lorraine settled in other French towns, including some in Savoie.

By the turn of the 20th century, Jews were living peacefully in Savoie. During the Second World War, networks were set up to cross into the free zone, and then across the Swiss border around Annemasse and Novel.

According to a 1970 study by Bernhard Blumenkranz, Chambéry’s Jewish community numbered 120. The Chambéry synagogue is located in impasse Chardonnet.

Sources : « Les Juifs en Savoie du moyen-âge à nos jours » by Jacques Rachel, Encyclopaedia Judaica

Annemasse, a town on the border with Geneva, developed mainly in the early 20th century.

The Jewish presence in Annemasse probably dates back to the Middle Ages, but was quite small. This changed with the emancipation of the Jews of France following the Revolution, and especially with the arrival in the region of Jews from Alsace-Lorraine.

By the turn of the 20th century, Jews were living there peacefully. During the Second World War, networks were set up in the Annemasse and Novel areas to cross into the free zone and then over the Swiss border.

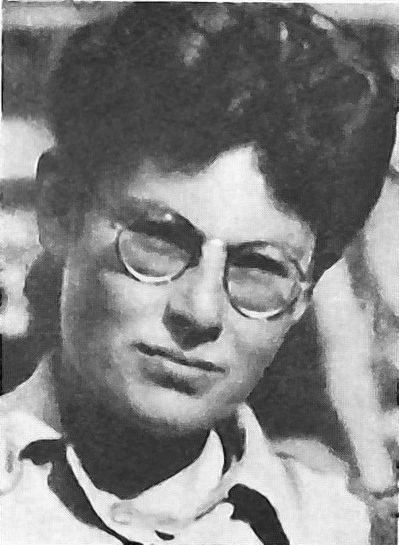

Among them were the Resistance couple Flore and Georges Loinger, members of the OSE and the Bourgogne and Garel networks, who smuggled 350 Jewish children into Switzerland via Annemasse. They were assisted by Tony Gryn, Mila Racine and her brother Emmanuel Racine.

Mila led convoys of children and was arrested during one of these missions in 1943 and incarcerated in the Pax prison. She died two years later in Mauthausen. A park in her memory was inaugurated in 2023. An elementary school in Annemasse bears the name of Marianne Cohn, a Resistance fighter who also took part in the rescue of Jewish children in Savoie, murdered by the Gestapo.

Jean Deffaugt, mayor of Annemasse during the war, was recognized as Righteous Among the Nations for having saved Jewish children imprisoned by the occupiers and threatened with deportation. A square was named in his honor.

According to a 1970 study by Bernhard Blumenkranz, Annemasse’s Jewish community numbered 60. Formerly worshipping in neighboring Geneva, the Jews now have their own synagogue . Annemasse town hall dedicated the year 2022 to the memory of Marianne Cohn.

A tribute was paid to the courage of Mila Racine and Marianne Cohn at an event organized by the synagogue in 2023, to mark the inauguration of the park. A Maison de la Mémoire is due to be inaugurated in 2025, on the site of the former Pax prison.

Sources : « Les Juifs en Savoie du moyen-âge à nos jours » by Jacques Rachel, Yad Vashem, Times of Israel

This beautiful Alpine town between lake and mountains has been a favorite of residents and tourists alike for centuries.

The Jewish presence in Annecy probably dates back to the Middle Ages. They lived on the right bank of the Thiou, outside the fortified city walls. Rue des Juifs (“Street of the Jews) later became Quai de l’Evêché. During the Great Plague, Jews were accused of poisoning fountains and thrown into prison.

Although the French Revolution brought Jews back to France, the Jewish population of Savoie increased mainly as a result of the 1870 war.

As a result, many Jews from Alsace-Lorraine settled in other French towns, including some in Savoie.

By the turn of the 20th century, Jews were living peacefully in Savoie. During the Second World War, networks were set up to cross into the free zone, and then across the Swiss border around Annemasse and Novel.

Among them, Mila Racine, who joined the Resistance in Annecy, was one of the founding members along with her brother Emmanuel Racine, Tony Gryn and Georges Loinger. She led convoys of children and was arrested during one of these missions in 1943.

According to a 1970 study by Bernhard Blumenkranz, Annecy’s Jewish community numbered 360.

This figure doubled in fifteen years, thanks in particular to the arrival of Jews from North Africa. Annecy’s current synagogue is located on rue de Narvik.

Sources : « Les Juifs en Savoie du moyen-âge à nos jours » de Jacques Rachel

As its name suggests, Aix-les-Bains is a renowned French spa.

The Jewish presence in Aix-les-Bains probably dates back to the Middle Ages, but was quite small. This changed with the emancipation of the Jews of France following the Revolution, and especially with the arrival in the region of Jews from Alsace-Lorraine.

The Jewish community of Aix is best known for its Chachmei Tsorfat Yeshiva (“The Yechiva of the Sages of France”), founded in 1945 by Rabbi Moshe Leybel and Rabbi Ernest Weill to welcome young survivors of the Holocaust who were then living in the city. Since then, it has welcomed thousands of students.

According to a 1970 study by Bernhard Blumenkranz, the Jewish community of Aix-les-Bains numbered 350. Today, the community has several small synagogues of different rites.

In 2024, at Place Maurice-Mollard, period documents and photographs illustrating the writings of Aix Resistance fighter Aimé Pétraz were displayed as part of the ‘Aix liberated 21.08.1944’ exhibition.

Sources : « Les Juifs en Savoie du moyen-âge à nos jours » de Jacques Rachel

Hameenlinna is an old Finnish town, known for the many lakes that run through it and the surrounding area. But also for the traces of its medieval life and the Hame Castle.

Before Finland’s independence, Russian soldiers, including Jews, were stationed here. The town’s cemetery , founded in the 1770s, has a Jewish plot.

Russian soldiers of the Jewish faith are buried there, with most of the graves dating from the early 20th century. The cemetery is now part of a park that still contains these graves.

Hamina is the easternmost town in the country and dates back to at least the 14th century. Today, it is known for its port, forestry industry and special climate.

Russian soldiers were stationed here before independence, as the town lies a few kilometres from the present-day border with Russia. The town’s cemetery , founded in 1773, has a Jewish plot. Russian soldiers of the Jewish faith are buried there, with most of the graves dating from the early 20th century. The Jewish plot was vandalised in 2020.