Haguenau is one of the oldest Jewish communities in Alsace. The Jews lived there almost without interruption since the Middle Ages, probably in the 12th century, and enjoyed the same freedoms as the other inhabitants, except for a few episodes, mainly of a more national scope, affecting all regions.

The first synagogue was confiscated during the expulsion of 1349. Upon their return, the Haguenovian Jews built a synagogue in a house at 8 rue du Sel. This was rebuilt after a fire in 1676 and served as a place of worship until 1820, when the present synagogue was built.

On the eve of the Second World War, there were 600 Jews in Haguenau. The Shoah decimated a quarter of them. Destroyed during the Occupation and damaged by a bombing raid at the Liberation, the synagogue was restored, with its outbuildings, to its former glory in 1959. Jewish life resumed after the war, marked by the inauguration of several rooms and Sifre Torah. Thus, in 1968, the community was composed of nearly 300 people, reinforced in particular by the arrival of Jews from North Africa. At the turn of the century, 700 Haguenovian Jews lived there.

The Jewish cemetery of Haguenau is one of the oldest in Alsace, containing more than 3,000 graves dating back to the 17th century. Many of the graves were vandalised and destroyed during the war.

In 2021, guided tours and a two-day historical symposium marked the synagogue’s bicentenary.

A concert combining liturgical and folk music was held at the Haguenau Synagogue on 22 June 2025, during a meeting between the Le Chant Sacré choir and the Klezm’hear ensemble.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr, Encyclopaedia Judaica

The Jewish presence in the villages surrounding Haguenau seems to date at least from the 14th century. In Ettendorf in particular, two Jewish families are recorded in administrative documents in 1449.

In the Middle Ages, Ettendorf was home to a large Jewish community and many scholars who came to study in its famous rabbinical school, sometimes with more than a hundred students.

Ettendorf is also home to one of the oldest Jewish cemeteries in the region. It was built in the 15th century, at the same time as the other large Jewish cemeteries in Alsace.

At the time of the great census of 1784, 124 Jews lived in Ettendorf. However, wars and the rural exodus caused their gradual departure over the centuries. From 37 Jews in 1868 to one family in 1926.

In 2019, the city dedicated an exhibition “On the traces of Jewish memory in Ettendorf” directed by Dorah Husselstein. Documents, objects and testimonies were presented.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, judaisme.sdv.fr

The Jews of Erstein were not allowed to settle in the city until 1850. Some were allowed to work there during the day, but had to return in the evening to the towns in the region that were more open to Jewish emancipation.

The synagogue was inaugurated in 1882. It was destroyed in April 1941 by the Nazis, its contents auctioned off at that time. Of the 100 Jews living in Erstein in 1939, only 60 were still present at the Liberation.

The place of worship was not rebuilt until 1957 and is still in use, albeit in a limited way, today. A certain amount of Jewish life was thus maintained in the 1960s, but gradually the number of worshipers diminished.

The Jewish cemetery was established in 1904 on the road to Osthouse.

On 29 July 2025, the Grand Ried tourist office organised a visit to the Erstein synagogue to raise awareness of Jewish rituals among local residents.

A square named after Huguette-Henriette-Metzger was unveiled in front of the synagogue, in tribute to this young girl born in Erstein in 1931, who was deported and killed in Auschwitz in 1944.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr, dna.fr

The Jewish presence in Diemeringen seems to date from the 17th century. Only 14 Jewish families lived there on the eve of the French Revolution.

The community of Diemeringen was organized – synagogue, religious school and mikveh – around the rue des Juifs (today rue du Vin). The community grew mainly in the 19th century, reaching 139 people in 1870. The war, and then the rural exodus, concentrated the population in the large cities, and the community dropped to 94 faithful in 1910.

The synagogue was built in 1867. Restored in 1906, it was ransacked during the Second World War. It was returned to worship in 1947. Services are still sometimes held there, despite the few Jews still living in the city.

Adjacent to the synagogue are the mikveh and the rooms that housed the Jewish school. On the outskirts of the town, next to the communal cemetery, is a Jewish cemetery probably dating from 1750.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr

The Jewish community of Dambach-la-Ville dates back to the seventeenth century and so is the synagogue which was renovated in 1850. After the community disappeared, it was donated to the town in 1947 and transformed into a theatre.

Renovation work, including the installation of an air conditioning system, led to the discovery in 2012 of a formidable treasure: a genizah (a ritual repository of writings and objects bearing the name of God, which cannot be thrown away or destroyed. They are deposited in a cache, awaiting burial in the cemetery) collecting objects and documents ranging from the late 16th century to 1894. The old pieces of paper and objects that were in the genizah are deposited in the truck and destined for the waste disposal center. The curiosity of a passerby and the involvement of historian Yvette Beck-Hardweg prevented the documents from being thrown away. The Société d’Histoire des Israélites d’Alsace et de Lorraine (SHIAL) obtained the support of the municipality and the DRAC to extract all the documents, to package them and to store them in the “Maison des Sœurs”. Nearly 900 objects were thus catalogued and restored. Among them, 250 mapoth or fragments of mapoth as well as a dozen Torah mantles and 300 books, some dating back to 1592.

The major part of this incredible collection, made up of objects, some of which are extremely rare, is on display at the Jewish Museum of Strasbourg, thanks to a donation made by the municipality of Dambach-la-ville and the involvement of its mayor, Gérard Zippert.

The former synagogue in Dambach has been converted into the Georges Meyer Cultural Centre. It offers a varied cultural programme throughout the year, with shows, theatre and opera broadcasts.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr

The first mention of a Jewish family in Brumath dates back to 1562. Documents from the end of the century mention the presence of a Jew named Susskind. In 1693, 4 Jewish families were registered in Brumath and, in 1766, their number rose to 9.

The French Revolution gave Brumath, as in the rest of the country, access to citizenship for Jews. This allowed the Jewish community not only to settle but to grow, becoming one of the largest in the region, with a rabbinate that also served the surrounding communes. As in most towns in the region, this number declined following the defeat of 1870, as a large part of the Alsatian Jews preferred to remain French.

The synagogue was built in 1845, in place of an old house of prayer. And two years later, the Israelite school, with a class for girls and one for boys. During the German occupation, the synagogue was damaged and desecrated. In the post-war years, it was first used as a food store.

Renovated in 1957, it was then re-inaugurated and returned to worship. At that time, there were about a hundred Jews in Brumath. Since 1998, a possible project to transform the synagogue of Brumath into a center for the conservation of Alsatian Jewish heritage has been discussed, given the numerical decline of the community and its uncertain future as a place of worship.

The synagogue occasionally opens its doors to visitors, as was the case, for example, on the eve of Sukkot in 2021, when a succah was built in its courtyard for the occasion.

In 1880, a Jewish cemetery was established, as burials had previously taken place in the Ettendorf cemetery. It is located 1 km outside the village. In 2004, 92 graves in this cemetery were desecrated, causing a wave of indignation throughout the region.

The Memory Watch network was set up in Bas-Rhin and Haut-Rhin in 2019. Some of its members are now working to preserve the synagogue and Jewish cemetery.

During the European Days of Jewish Culture in 2025, the Brumath synagogue opened its doors on 7 September to raise awareness of this place and to exhibit works by Italian artist Tiziana Pavan evoking different moments in Jewish life.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr and dna.fr

The Jewish presence in Benfeld dates back from the Roman Empire. During the Middle Ages, the community was lively and as important as the one in Strasbourg. The Jews were expelled from the city during the 1349 black plague, then drawn or burned on the same year during the Saint Valentin massacre. From this date, Benfeld was forbidden to Jews until the eighteenth century.

The community reformed in Benfeld in the nineteenth century. It grew until 1910 when there were about 200 Jews in the city. There were 98 in 1953, and today about twenty.

The synagogue was built in 1846 and extended in 1876. In 1922, the synagogue was decorated by the local artist Achille Metzger who took inspiration from the Florence’s synagogue frescoes. Thanks to the courage of the city’s mayor, the synagogue went through the war without being sacked. It is remarkably one of the only synagogue of the region which wasn’t destroyed. The Sésame Award, which recognises the enhancement of religious buildings throughout France, was awarded on 19 June 2024 to the Benfeld Synagogue.

Many efforts have been made by the regional authorities and the communities to (re)discover the Jewish cultural heritage of Benfeld. For example, during the European Days of Jewish Culture in 2021, the ancient Jewish cemetery was opened to the public for the first time in a long time, allowing about 50 people to visit it. On 8 September 2024, during European Jewish Culture Days, a tour was organised of the Jewish cemetery in Benfeld. An annual ceremony is also held there in memory of the victims of Nazi crimes.

Sources : dna.fr

Banned from the communes attached to the bishopric of Strasbourg until the French Revolution, the Jews made a timid return to the region afterwards. Of the 800 Jews present in the surrounding villages in 1784, there were none in the town of Barr.

Nevertheless, the town gradually welcomed Jews, mainly from Zellwiller, allowing a community to take shape in the second half of the 19th century.

Thus, a prayer room was opened in 1860. In 1878, a synagogue was built, to which was added a meeting room and a mikveh. The community continued to grow, even though many Jews left Alsace after the defeat of 1870 to remain French.

As a sign of this evolution, from 1910 to 1944, the town of Barr hosted the seat of the rabbinate, succeeding Dambach-la-Ville.

Nevertheless, the Jewish population declined and in 1920, there were less than 400 Jews in Barr and its region. On the eve of World War II, only about 40 Jewish families lived there. During the Occupation, 25 Jews fell victim to the Nazis and the synagogue was devastated.

Although efforts were made after the war to redevelop the synagogue, the building was ultimately demolished in 1982. This decision was made after a corner pillar collapsed. In order to preserve some of the elements and highlights of the Barr synagogue, these stained glass windows were salvaged and added to the oratory in the Meinau. Sculptures, including the Tables of the Law, were preserved in the park of the Elisa Foundation in Strasbourg.

Most of the Jews of Barr were buried in the Rosenwiller cemetery.

Sources : http://judaisme.sdv.fr

The Jewish community of Balbronn is registered in the censuses of the city since 1665. Some medieval houses of the city center still bear the traces of mezuzot. The old synagogue is located 47-48 Balbach street, in what is commonly called “House of the Jews”. The house dates from 1638, although it started serving as a synagogue only in 1730. The prayer hall was on the first floor, the mikveh in an adjacent house.

Therefore, Balbronn has two synagogues, the old synagogue from the seventeenth or eighteenth century and the new one, located on rue des Femmes.

The Jews of Balbronn constituted up to the fifth of the local population (at its peak in 1882, the community was of 207 on a total of 997 inhabitants) and they seemed to have got along harmoniously with their neighbours.

The new synagogue was built in 1895 in a neo-roman style. Sacked by the Nazis during the Second World War, it was renovated and reopened in the 1960. The building is registered national heritage since 1999 but the synagogue isn’t in service since 1989. The synagogue can be considered a jewel of the neo-roman style and more particularly of the Rundbogenstil style from the nineteenth century.

In 2024, in response to the desecration of the Jewish cemetery on 2019, a square was renamed after Grand rabbi Jules Bauer (1868-1931) , a native of the commune, in the presence of his descendants. Participants at the event were welcomed with a presentation. The work of the pupils of the Collège Grégoire de Tours on the biographies of those deported and murdered at Auschwitz-Birkenau was presented to those attending the ceremony. Stolpersteine were laid in memory of Edmond Lévy, Rosa and Moïse Roth, Rosa, Arthur, Irène and Yvonne Lévy, Robert Schwartz and Reine Weil.

A memorial stele in tribute to the victims of the Holocaust was inaugurated in front of the Balbronn town hall on 29 June 2025.

Jews settled in Pergola in the thirteenth century. The building that housed the synagogue can still be seen on Via Don Minzoni, 9. A Jewish cemetery was identified on the road to Mezzanotte, an excavation operation is ongoing.

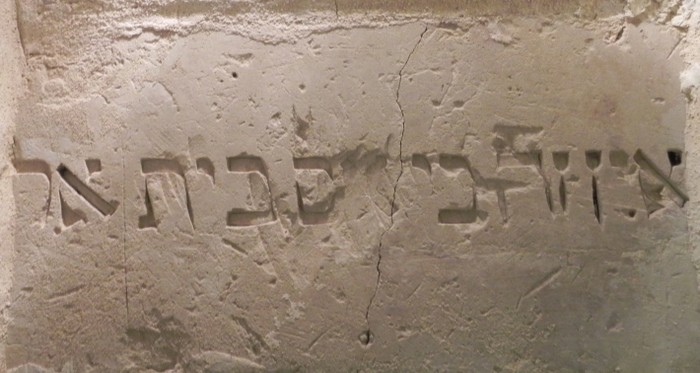

There are little remaining traces of the Jewish presence in Macerata. You can nevertheless visit the city’s library which contains archives mentioning the presence of a Jewish community in the city since 1287. The city hall houses a tombstone with an Hebrew inscription from 1553, referring to the passing of Rabbi Avigdor. The tombstone was probably transferred here from the old Jewish cemetery of Cappuccini Vecchi.

The Jewish ghetto was located where Vicolo Ferrari today stands.

In 1943, 40 Jews -mainly foreigners, were arrested in Macerata and the surrounding villages. Only 3 came back from deportation.

Jews settled in Corridonia in 1436. The only remaining trace of this community is the ghetto entry gate located Via Antonio Mollari.

Sabbioneta is a special city: it was created in the sixteenth century by prince Vespasiano I Gonzaga Colonna according to the architectural principles of the Renaissance. In this “ideal city”, a Jewish ghetto was included. In 1551, Tobias Foa opened a Hebrew printing house in Sabbioneta. Although the community was described as “lively” in the nineteenth century, there were a very few Jews remaining in Sabbioneta at the eve of the Second World War.

Sabbioneta’s synagogue is from 1824, is located where the ghetto once stood. After years of negligent caretaking, it was renovated in 2010. Although nothing indicates its function from the outside, the prayer hall is splendid. Since 2008, the building is protected by UNESCO.

Naples is known for Mount Vesuvius, the volcanic enthusiasm of its people, the pages of Elena Ferrante and more recently, the films of the great director Paolo Sorrentino.

The Neapolitan Jewish presence dates back to at least the first century, as mentioned in the texts of Flavius Joseph. As archaeological finds from 1908 attest, Jewish life in the 4th century was significant. Graves from this period have been found with inscriptions in Greek, Latin and Hebrew. These inscriptions are decorated with menoroth and citron.

The Jewish community had a synagogue and a school as early as the 11th century in the giudecca in San Marcellino, near Via dei Tintori. During the visit of Benjamin of Tudela in 1159, he noted the presence of 500 Neapolitan Jews. Despite some exactions at the end of the 13th century, the situation of the Jews in the Middle Ages was relatively happy and egalitarian. This motivated the arrival of migrants, especially after the Spanish Inquisition.

A Hebrew printing house was opened at the end of the 15th century. At that time, about twenty books were published by the printers Gunzenhausen, Soncino and Katorzo. These were mainly biblical texts, but also a Hebrew translation of Avicenna’s medical texts. Nevertheless, in 1510 the Neapolitan Jews were expelled. The resettlement of the Jews was temporarily allowed from 1735 to 1746. The Jewish community managed to take shape in the 1830s, thanks to the Rothschild family. A synagogue was inaugurated in 1864, in Palazzo Sessa, which remains the community’s place of worship today. The ancient Jewish cemetery is located at Via Cimitero Israelita

The Jewish community was mainly present in Via Cappella Vecchia. About a thousand Jews lived in Naples in 1931. Some Jews were murdered during the Holocaust, but the Allied landing saved the vast majority of them. As an important Allied base after the 1943 landings, many Jewish soldiers helped rebuild the community. At the end of the war, 534 Neapolitan Jews were registered. In 2026, there were only 200.

As in many European cities, Naples has been affected by the importation and exploitation of the conflict between Hamas and Israel following the pogrom of 7 October. Israeli tourists were threatened and the synagogue was targeted by a terrorist plot in 2025.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, JC, Times of Israel

A Jewish community established itself in Soragna when Jews were expelled from Parma in 1555 and from Piacenza in 1570. In front of the city’s castle, one can find the oratory dating from 1584, since then transformed into a synagogue and Jewish museum. You’ll find there a great collection of crafted objects, as well as documents retracing Jewish life in this region since the sixteenth century.

Fausto Levi, the president of the Jewish community of Parma, began in the late 1970s to collect archives attesting to the presence of Jewish life in the area and the locations of the ancient synagogues. The results of this research have since been put on permanent display in the Jewish Museum in Soragna.

The Jewish cemetery of the inhabitants of Soragna is located in the Argine countryside. It dates back to 1839.

A famous inspiration for Stendhal, Parma is a city with a wealth of cultural institutions: museums, theatres and concert halls. It was also the regional birthplace of Verdi, who is celebrated here every year at a festival. And, of course, Parma is also famous for all the culinary specialities that go with its name.

History of Parma’s Jews

The Jewish presence in Parma probably dates back to the 14th century. They played a major economic role in the region, protected by the Visconti and Sforza families. A synagogue was built in 1448. However, the city witnessed a rise in anti-Semitism during this century, leading to their expulsion from Parma in 1504.

It was not until the Napoleonic conquests of the region that the Jews were able to resettle in Parma. As a sign of this access to the same rights as Italian citizens, a synagogue was built in Parma in 1866. The Jewish cemetery has been in use since the 19th century.

The Palatine Library has some very ancient texts, some of which bear witness to the long history of Italian Jewish cultural heritage. YIVO in New York and the Alliance Israélite Universelle library have extensive archives on European Judaism, but the Palatine Library is home to rare medieval texts. In a spirit of discovery and sharing, many researchers visit the library, including a delegation from YIVO in 2024, which set out to discover these rare texts.

Visiting Parma

Coming from the train station down the Strada Giuseppe Garibaldi, you will see the Piazza della Pace on the right, which you will return to a little later. Turn left onto Via Macedonio Melloni, home to a number of small museums, including one dedicated to the Resistance and the very interesting Puppet Museum, which tells the story of the evolution of this art form in Italy, with its reference characters for each town and village.

Then, over the centuries, the number of characters was reduced to a handful of celebrities made of wood and fabric, loved by children all over Italy and far beyond thanks to the advent of television. The museum displays how great artists such as Chaplin and Josephine Baker worked with puppets on stage.

A 100-metre turn to the left brings you to the impressive Piazza del Duomo, where the Museo Diocesano, Palazzo Vescovile, Palazzo Dalla Rosa Prati, the octagonal baptistery and Parma’s beautiful cathedral stand side by side.

The cathedral features a mural depicting God and the famous Hebrew tetragrammaton “Yahweh”.

Take Via XX Marzo from the cathedral and cross the Strada della Repubblica, a busy shopping street, before turning into Piazzale Cervi and arriving at the synagogue.

The synagogue was inaugurated in 1866, celebrating the return of the community after an absence of two centuries. During the Second World War, the synagogue’s artefacts were hidden in the Palatina Library . Some were returned to the synagogue after the war, while others went to the Fausto Levi Museum in Soragna.

Next to the synagogue are a number of small, discreet streets with cafés where locals and tourists alike enjoy typical dishes, including meats and cheeses bearing the town’s name.

Then head up the left-hand side of the Strada della Repubblica, with its pretty Piazza Garibaldi covered in palace entrances and the Palazzo del Governatore, a historic venue for modern art exhibitions.

We cross Piazza della Steccata, returning to the Strada Garibaldi from the start of our visit, towards the church of Sant’Alessandro and the Basilica of Santa Maria della Steccata. Immediately afterwards, we arrive at the magnificent Reggio Theatre and behind the Piazza della Pace. There are two impressive sculptures in Piazza della Pace. The first pays homage to the Partisans, while the second celebrates Giuseppe Verdi and the various musical practices.

The imposing Palazzo della Pilotta, behind the sculptures, is home to a number of important cultural attractions, including galleries, theatres and museums, including the Palatina Library, which houses some very ancient Hebrew manuscripts. A single ticket gives you access to the library and the other areas of the building.

On leaving the building, cross the River Parma over the Verdi Bridge to reach the Parco Ducale, the green lung of the city centre, where you can wave goodbye to the Palazzo Ducale on the right and enjoy the walk to the Fontana del Trianon.

Then turn right again to reach the Bridge of Nations, with its many flags, on which, in 2024, the Israeli, Palestinian and peace flags will stand side by side. A touch of hope before returning to the station.

One of Oria’s gates, Porta di Ebrei (or Porta Taranto) leads to the old giudecca of the city. The gate dates from the fifteenth century and bears a bronze mezuzah. There are no traces left of the Jewish community in Oria, but a stroll in Santa Giudea little streets, the old Jewish neighborhood, will let you see the medieval architecture of what was once one of the biggest giudecca in Italy.

The site where stood the synagogue of the quarter was recently unveiled, via Francavilla.

Historians believe – although the exact dates are still lacking – that there was a Jewish quarter in the small town of Manduria between the thirteenth and seventeenth centuries. It is likely that the Jewish community of Naples found refuge there after its expulsion from the kingdom.

The giudecca was not separated from the rest of the city by walls until the expulsion of 1510. At the request of the council of the city, the inhabitants returning to the city after the expulsion transformed their Jewish quarter into a ghetto isolated from the rest of Manduria.

The giudecca and the synagogue in the central square, are still visible nowadays. The Jewish quarter was built around what is today the main Church of the city, Chiesa Madre.

As in the city of Trani, for example, this intermingling of Jewish and Christian homes in medieval times is a sign that the two communities lived in goodwill and enjoyed commercial ties until the expulsion.

In the eighteenth century, the synagogue was desecrated and transformed into a manor. However, signs on the portal, such as a floral motif, are representative of the synagogal art of this region. In addition, a menorah is still visible. The synagogue is now a private building, but can be visited in advance by contacting its owner.

In the summer, it is possible to visit the giudecca with a guide by contacting the tourist office of Manduria .

Source: Francesco Pio Gennari – Visit Manduria

Lecce had one of the most prominent Jewish settlements in the Neapolitan kingdom before the expulsion of the Jews. Though there is no evidence of a Jewish presence prior to the 15th century, there are traces of its existence in Lecce at the time of the Normans (G. T. Tanzi, “Gli Statuti della Città di Lecce,” p. 19, Lecce, 1898).

Their occupations were mostly textile dyeing (silk and wool), cattle raising, and money lending. They were not allowed to own real estate or engage in the higher callings. They were also forced to wear distinguishing badges on their clothes. Still, the Jews were protected by the law and seem to have been free from persecutions. When the last Count of Lecce, Giannantonio del Balzo-Orsini, died in 1463 and the city came under the direct rule of Ferdinand the 1st, King of Aragon, there was an outbreak of violence against the Jews. During this time the ghetto was sacked, a number of Jews were killed, and the remainder were driven away.

In 2016, on the site of what once was the giudecca synagogue, opened the Palazzo Taurino – Jewish Medieval Museum of Lecce . The museum explores the everyday life of the Jewish community in Puglia between the ninth and fifteenth centuries. Some elements were excavated from the ghetto -such as a mezuzah or scriptures in Latin or Hebrew. You can as well visit the mikveh which was discovered under the building. As the museum is located in the center of the giudecca, it is a good starting point for your visit of the neighborhood. The streets names still bear traces of the medieval Jewish community. Via della Sinagoga, Via Abramo Balmes (in homage to the Jewish physician born in Lecce), Vico della Saponea (soap makers, principal activity of Jews in Lecce). The museum provides guided tours of the giudecca.

Sources: JItaly

Few people know it, but the Jewish Museum of Lecce is built in the area where the Jewish community was located in the Middle Ages. A look back at the ancient history of Lecce and a discussion of the museum’s plans and ambitions with Fabrizio Lelli, Associate Professor of Hebrew Language and Literature at the University of Salento

Jguideeurope : Can you tell us how the museum was created?

Fabrizio Lelli : The Jewish Museum of Lecce (hereafter the JM) was opened in May 2016. The project started from the initiative of private investors who aimed to cast light on a little-known piece of local history. Unlike most Italian cities, Lecce seems to have erased every trace of its Mediaeval past. In spite of the almost total absence of material testimonies, archives document the significant role played by Jews in Lecce over ten centuries, when the town was an important centre of economic and intellectual activities.

The Jewish community was among the most vital groups that populated Mediaeval Salento: a copious and strongly rooted presence since the beginnings of the Jewish Diaspora in Western Europe dating to Roman times. Throughout the Middle Ages, Jews played significant social roles – particularly from the 14th century onward, when they settled in the district where the museum is currently located.

The project is constantly growing, and, thanks to the help of those who believe in it, the museum has become a cultural centre that organises events and exhibitions addressing both locals and international visitors. We focus on Jewish identity and intercultural dialogue from the past to the present. School teachers and students are welcomed to attend seminars, in-depth workshops, temporary exhibitions and theatre performances.

Are there educational projects proposed by the museum and how is the city of Lecce participating in the sharing of Jewish culture?

Since its opening, the Jewish Museum has always offered to locals and non-locals a wide range of educational projects, including historical itineraries, guided tours, and workshops aimed at students of primary and secondary schools. Our activities, varying according to the age of the participants, aim to develop an engaging and stimulating approach to the knowledge of the Jewish history, traditions and culture of our territory. Most recently, the JM added to its educational offer the virtual reproduction of the ancient Jewish district of Lecce. By means of visual technologies, visitors can immerse themselves in medieval Lecce and take a virtual stroll in the ancient Jewish district.

Can you share a personal anecdote about an emotional encounter with a visitor or researcher during a previous event?

Working with visitors from around the globe offers us many emotional encounters, such as the many meetings with the descendants of the refugees that were welcomed in the DP Camps of Salento between 1945 and 1947. If I had to choose one, I would certainly mention the time when a local visitor shared with us a story about her grandmother. Even though she was Christian Catholic, she had the tradition of lighting a candle on Friday evenings, thus suggesting that in Lecce the traces of Jewish converts survive until nowadays. This is a demonstration of the important role played by our museum to revive the lost traces of a long-forgotten community.

Unlike other cities in the region of Apulia, there are now very few traces of the Jewish presence in Bari, although we know that the community was very developed. The city was, in the 12th century, a recognized center of Talmudic studies.

The Via della Sinagoga, which housed the place of worship of the community and is now renamed Via Sabino, attests to the importance of Jewish life in Bari.

In the Provincial Museum of the city, you can gaze at the steles of the Jewish cemetery which is located in the district of San Lorenzo. This cemetery probably dates back to the 8th century, and was therefore one of the oldest in the region.

Note that in 1943 a number of Jews from Italy and Yugoslavia found refuge in Bari. At the end of the Second World War, a refugee camp was established there. Then, after 1945, the surroundings of Bari were a point of “illegal” departure towards Palestine.

The Bari Tourist Office offers a guided tour of the city’s Jewish heritage.

Source : Jewish Virtual Library

Rakovnik is located between Prague and Plzen; 32 miles west of Prague, and 30 miles northeast of Plzen. Jews are on record as living in Rakovnik since 1441. Between 1618 and 1621, three Jewish families from the nearby town of Senomaty came to live at Rakovnik. In 1690, there were 38 Jews living in the town, and in 1724, seven Jewish families had made Rakovnik their home.

The Jewish community was organized sometime during the 17th century but was officially recognized in 1796. After 1830 there were 14 families who made up the Jewish community; by the middle of the century, particularly after the emancipation of Austrian Jewry in 1848 and the subsequent removal of residence restrictions, the number of families living in Rakovnik rose to about 30. At that point there were 10 Jewish houses located around the synagogue, in the northern part of the old town.

The Baroque-style synagogue was built in 1763 on the site of a prayer house that had existed since 1736. The synagogue was rebuilt and expanded in 1792 and in 1865; later, in 1917, the synagogue underwent further refurbishment. The synagogue was damaged by fire in 1920 and repaired for the last time in 1927. It was ultimately in use until World War II. A community house, which adjoined the synagogue, contained the regional rabbinate offices and the Jewish school. The cemetery, which had been consecrated in 1735 on a hill south-east of the town, was enlarged 3 times: in 1745, 1856, and 1891. A funeral hall was added at the beginning of the 20th century, along with a burial ground for urns with ashes. Other communal institutions and resources included the chevra kaddisha and a women’s society for charity and welfare work.

In March 1939, the region of Bohemia and Moravia, which included Rakovnik, became a protectorate of Nazi Germany, ushering in a period of discrimination and violence against the region’s Jews. Between 1938 and 1941, the Jewish community made a unique agreement with the Czech church in which the synagogue building served the Jewish community on Saturdays and the Christians on Sundays.

Beginning in 1942, the Jews from Rakovnik were deported along with the Jews of Prague to the Terezin (Theresienstadt) Ghetto. From there they were sent to concentration and death camps, where most perished. Before the expulsion to Terezin, 239 documents, 30 books, and 150 ritual objects were transferred from the community to the Central Jewish Museum in Prague.

Jewish life was not revived in Rakovnik. From 1942 until 1950, the synagogue building functioned as a Hussite church. In the 1990s, it was converted into a concert hall; the women’s gallery and the adjoining community house were turned into an art gallery.

In November 2024, a sefer torah that was saved during the war and taken to Thousand Oaks in the United States was brought back to Rakovnik. A ceremony was held to mark the occasion in the old synagogue, the first since the Shoah.

Source : Beit Hatfutsot Museum, Israel

Hermanuv Mestec is located in Bohemia, 56 miles south from Prague. The Jews began settling there in the fifteenth century, and the community reached its peak in the nineteenth century. The Baroque-style synagogue was built in 1728 in the center of the ghetto, then reconstructed in neo-Roman style in 1870. It was closed in 1939 and served as a warehouse until the 1990s. Today it houses an art gallery.

The Jewish presence in Breclav dates to the sixteenth century. The ghetto, constructed in the seventeenth century, can still be visited. The neo-Roman style synagogue was built in 1888. Closed by the Nazis, it served as a warehouse for a half century.

The synagogue today houses a cultural center, an exhibition hall, and an auditorium. In 2000, a plaque was affixed in the synagogue’s entrance to honor the memory of the Jewish community of the city, exterminated during World War II.

The presence of a Jewish settlement in Holešov dates back to at least the 16th century. Holešov hosted one of the most important Jewish communities in Moravia, a centre of culture and education. The Jewish population of the city reached 1,700 (one third of the whole) by the mid-19th century.

In the northern part of the town, some houses of the old ghetto can still be seen. The Renaissance-style synagogue built in the sixteenth century was restored in 1960 and houses an exhibition about the Jewish community of Moravia.

The Jewish cemetery on Hankeho street has approximately 1000 tombstones, the most ancient dating from 1647.

Every year in August a festival for Jewish culture takes place. You will find more information about this event on http://www.olam.cz/.

Jews began settling in Lomnice in 1656. The eighteenth-century ghetto is composed of a square where one can still see the rabbi house and yeshiva.

The baroque-style synagogue was built in 1870 in the ghetto. Rehabilitated after the war, it was restored in 1997, and today it houses cultural events.

You can access the Jewish cemetery through Zidovske street. Dating from the eighteenth century, it is composed of about 500 tombstones, the oldest one from 1716. At the cemetery’s entrance, you can visit a small exhibition depicting the life of the Jewish community of Lomnice.

Dolni Kounice is a small town of Moravia located 115 miles south of Prague. Jews began settling there in the Fifteenth century and part of the ghetto has been preserved.

The Renaissance-style synagogue was built in 1652. Closed by the Nazis in 1940, it was restored in 1994 and today houses an exhibition hall. Inside the synagogue, you will observe arcades and Hebrew writings on the wall. There’s also Jewish cemetery in Dolni Kounice.

Velké Meziříčí is a small town of Moravia located 85 miles south-east of Prague.

The Jewish community started settling there in the sixteenth century. The ghetto is well preserved. You can still observe the walls and doors built in the eighteenth century. The Renaissance-style synagogue dates from the early sixteenth century. It was restored in 1995 and now serves as an exhibition center. The Grand Synagogue in neo-Gothic style was constructed in 1867.

The Jewish cemetery is located 300 meters from the city center. It was constructed in 1650 and the oldest tombstone dates from 1677.

Polná is located in Bohemia, about 70 miles south-west of Prague. Jews started settling in Polná in the fifteenth century. The ghetto was created in the seventeenth century, some houses can still be seen. The synagogue was built in 1682.

Destroyed by a fire, it was restored in the nineteenth century. It served as a place for worship until 1936, then was used as a store for confiscated Jewish property. It had a similarly sad fate under the communists, who used it to store chemical fertiliser. The synagogue was at one point threatened with demolition but was saved by the Club for Old Polná, which repaired it after 1989. In 1994, it was returned to the Federation of Jewish Communities. Between 2011 and 2014, the synagogue and the Rabbi’s Residence underwent major renovations as part of the Revitalisation of Jewish Landmarks.

Hartmanice is located South-West of Bohemia, in a mountainous region close to the Austrian border.

The synagogue of Hartmanice , also called “Mountain Synagogue” was built in 1881 to welcome the growing Jewish community of Hartmanice (about 10% of the population).

After the annexation of the region in 1938, the synagogue was confiscated by the Nazis. It was then a carpenter workshop and went through numerous degradations until its renovation in 2006. The interior was also renovated and houses a small museum retracing the life of the Jewish community of the region.

There is proof of a Jewish community in the Middle Ages in Sicily, particularly in the towns of Palermo, Messina, Taormina and Syracuse. This prosperous community was mainly in activities of commerce until their expulsion in 1492 by Ferdinand II. Only in 1989 will be unveiled one of the most beautiful treasures of the Jewish European heritage: Syracuse’s mikvah, this oldest known ritual bath of Europe up to this day.

The mikvah, long of 9 meters, can be found under the foundations of the Alla Giudecca hotel, at the center of what was once the Jewish quarter of Syracuse. It was probably covered in stones and hidden to the world’s eyes by the Jews themselves when they were expelled in 1492, maybe in the hope to find it intact at their hypothetical return. The ritual bath dating from the sixth century was adapted from a Byzantin basin, and was in use until the expulsion.

The visit of the mikvah starts in the hotel itself. You will have to go down 48 steps leading to a square room, whose vaulted roof is supported by four columns. The three ritual baths are surrounded by stone benches. Another two small rooms contain other baths, certainly used by more prosperous faithfuls.