The library in this university town of Heidelberg on the banks of the Neckar River contains a collection of Hebrew manuscripts dating back to the twelfth, thirteenth, and fourteenth centuries. Among the manuscripts are the songs of the Jewish troubadour Süsskind von Trimberg decorated with 137 illuminated miniatures. A memorial has also been built in the city to commemorate the victims of the Shoah.

Constituting archives

The “Central Archive on the History of the Jews in Germany”, previously kept in several locations, was brought together in 2021 in the premises of a former tobacco factory.

It was made available to the public in 1987 and contains valuable documents on the communities of the various German cities as well as documents of all kinds, such as letters from Jewish soldiers fighting on the front lines during the First World War or files on survivors of the Shoah. The German Ministry of the Interior, in coordination with Jewish institutions, is actively involved in the creation and maintenance of this library.

Trondheim’s synagogue is doubly unusual: it is the northernmost synagogue in Europe and the only one that has served as a train station, before the building became a synaogue in 1925!

Jews first settled in Trondheim in the 1880s. They quickly became very integrated, participation in all economical, social and cultural aspects of life. The Jewish community in Trondheim has never really recovered from the mass deportation of its members in March 1942. The city’s Jews were arrested by the Norwegian police and were detained at the Falstad camp, near Trondheim.

Today, the synagogue also welcomes the city’s Jewish Museum. The museum opened in 1997, celebrating the city”s 1000th anniversary. The latter proposes two permanent exhibitions. One devoted to the life of Jews in Trondheim and in the area. A second one focuses on the historical aspect of the Jewish community in Trondheim, especially during the Holocaust and the impact thereafter.

The museum also focuses on themes such as immigration, diversity, identity, integration, antisemitism before and now, and genocide together with the relationship between minority culture and the societal majority. Educational programs have been created by the museum and a large number of the museum’s visitors are pupils from primary school and high school as well as students.

A Holocaust Mémorial has been built at the city’s cemetery.

Interview with Tine Komissar, Manager of the Jewish Museum of Trondheim

Jguideeurope : Can you present us some of the objects shown at the museum?

Tine Komissar: Here are 4 objects I’m happy to present to you.

Prison suit. It was owned by Julius Paltiel of Trondheim (1924-2008). Most of the prison uniforms from the Nazi concentration camps during World War II were made in the sewing barracks at some of the larger concentration camps, including Dachau, Sachsenhausen and Ravensbruck. Despite the fact that the uniforms were made in different sizes, which were not marked on the suits, the suits were not distributed adapted to the size of the prisoners. The prisoners therefore had to adapt their own prison uniforms so that they fit better.

The marks on the suits consisted of a rectangular shaped patch, usually in cotton, with prisoner numbers in addition to a triangular-shaped patch with letters. The triangle referred to the different types of prisoners, and was color-coded; yellow triangle for Jewish prisoners, red for political prisoners, green for criminal prisoners, black for “antisocial” prisoners or Roms, pink for gay prisoners and purple for prisoners belonging to Jehovah’s Witnesses. The letters in the triangle referred to nationality.

This prison suit belonged to Julius Paltiel. In October 1942, he was deported by the Nazis from his home in Trondheim. He was detained at Falstad prison camp, before being sent on to Bredtveit prison in Oslo. In February 1943, he was sent with the ship D / S Gotenland to the concentration camp Auschwitz. Upon arrival, Julius was taken out to forced labor. He miraculously survived his stay in Auschwitz, and the death march of the Buchenwald concentration camp. In the weeks before the liberation in 1945, Julius went into hiding from the Nazis, who systematically picked out the Jewish prisoners in the camp. Everyone who was gathered was shot. The SS soldiers followed orders from Berlin that everyone should be exterminated.

In order not to be discovered, Julius tore off the yellow mark on the prisoner’s suit. He then took a non-Jewish mark from a dead prisoner and sewed it on his own suit to make it harder to detect that he was Jewish. This is why the suit has a red triangle, as shown in the picture. Buchenwald was liberated by American forces on April 11, 1945.

When Julius returned to Trondheim after the war, his family and many friends were gone. He resumed the family business, spending the rest of his life telling his story, including to thousands of young people around the country.

Wedding dress. It belonged to Malke Rachel Mahler (f. Leimann). She was born on April 2, 1896 in Śniadowo, Poland to parents Samuel and Lea Leimann. She came to Norway and Trondheim in 1916. Simon Mahler had already been in the country for three years. He was born on December 31, 1886 in Saldus, Latvia. He made a living as a transport trader and had traveled a lot both in Sweden and in Norway when the two met.

Malke and Simon married in 1916/1917. They settled in Tempe, having five children: Sara Bella (1918), Abraham Bernhard (1920), Salomon Hirsch (1922), Selik Elieser (1923) and Mina Scholamis (1927).

Malke, Simon, and the children Abraham, Selik, and Mina Mahler were deported and killed in Auschwitz during World War II.

Only Solomon and Sarah survived. Salomon managed to escape to Sweden. Sara was married to a non-Jewish man, and was not deported but imprisoned in several concentration camps in Norway during the war.

Cart, Production 1895 – 1905. The cart is probably from approximately 1900. Hennoch Klein came to Norway from Lithuania in the mid-1890s. He settled in Trondheim in 1901, after several years as a transport trader. Here, he started the business H. Klein in 1902, which operated in Trondheim until 1978. A continuation of the store, Kleins, is still run today by Henoch’s great-grandson, Robert.

Henoch Klein’s son, Josef, has said that every day he pulled the cart with him from his home in Øvre Møllenberg street to the family-run business, H. Klein, which in the 1910s was located by Bakke Bridge in Trondheim. The origin of the carriage is uncertain, possibly it was taken by the Klein family when they moved to Trondheim from Lithuania in the 1890s.

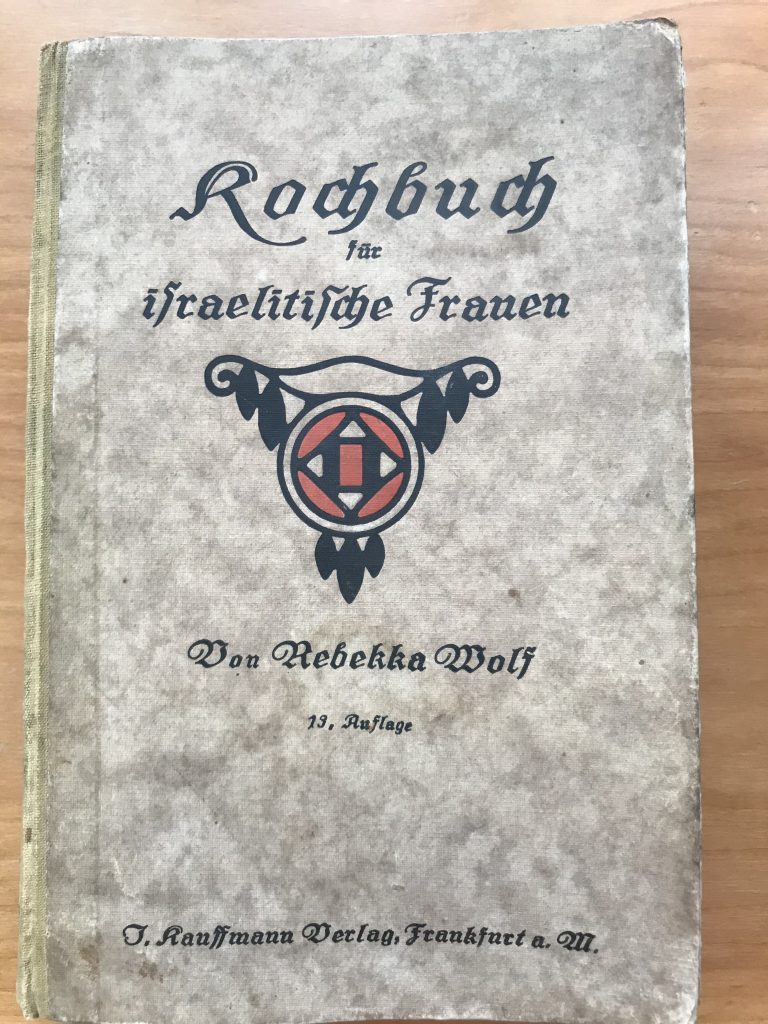

Kochbuch für israelitische Frauen, Rebekka Wolf (born Heinemann). A beautiful little cooking book with additional information on the blessings on shabbat and high holidays and advise on keeping a Jewish household. Also advise on making meat kosher. A special chapter is dedicated to the food on Pesach.

Can you tell us a bit more about the educational programs created by the museum?

The educational programs are directed for Norwegian student from 12 -25 years old. The Jewish Museum of Trondheim offers a variety of teaching programs for primary school, high school and college/university.

- “Norwegian-Jewish traditions, rites and culture”: An educational program which encourages active learning through activities with, for example, ritual objects. The pupils get to research the synagogue and study the similarities and differences between a synagogue and other places of worship. Through this learning resource, pupils will learn about Jewish symbols, holy days and traditions. If desired, pupils can learn about kosher foods. Educational films, which give an introduction into how Jewish holidays and ceremonies are celebrated in Norway, will also be shown.

- Home. Gone. The Jews from Trondheim: This program gives pupils an introduction to the history of the Jews from Trondheim and what happened in the city during the Second World War. By exploring the exhibition and the application, pupils will gain knowledge of Norwegian-Jewish history. The history is told through individuals and family histories. By doing this, the Jewish history becomes more concrete and alive. Pupils will also gain first-hand experience of historical source material which gives an insight into Norwegian war history.

- Nothing is as it seems – conspiracy theories and source criticism: Conspiracy thinking throughout world history has had catastrophic consequences, such as ethnic cleansing and genocide. Social media has made it easier than ever to spread conspiracy theories. In order to evaluate which information is reliable, you need skills in source criticism. This educational program makes use of film, websites and group activities in order to show pupils what characterizes conspiracy theories, and how we can identify them.

- Jewish footprints in Trondheim – Guided Tour: A historical journey through the downtown of Trondheim. Over the course of two hours, the guide will lead the pupils around central points in the city where Jewish families from Trondheim lived and worked. Through the guided tour, the pupils will get to know the Jewish history of the city, from when the Jews migrated to Norway in around 1880, through to the Second World War and up to the present day.The guide will have objects such as photographs and letters which belonged to the people who lived at the different addresses along the tour route. The tour gives the pupils an opportunity to reflect on ethical questions linked to human worth and attitudes, in addition to questions about how it is to be a refugee and immigrant in Norway in today’s society.

It was not until the law passed in 1814, prohibiting the entry of Jews into Norway, was revoked in 1851, that Jews could officially settle in Oslo. A small Jewish community was organised and recognised in 1892, with 29 members.

Following a separation of the community, two separate synagogues were opened in 1920. Norwegian Jewish cultural activity developed, especially through the press. First the monthly Israelitin in 1909, then Ha-Tikvah in 1929. A year later, the Community only numbered 852 persons.

During the Second World War, more than half of the Jews in Oslo managed to escape to Sweden, with the very active help of the Norwegian Resistance networks. The rest were deported and murdered.

In the aftermath of the Shoah, the survivors formed a community again. This community runs the synagogue, but also social services and welcomes tourist families for Shabbath dinners. School visits to the synagogue have been organised since the 1970s to enable Norwegian children to learn more about their country’s history.

Although there were less than 700 Jews in Oslo in 1968, the community experienced a revival in the 1980s, notably thanks to Rabbi Michael Melchior. An intergenerational dynamic, as illustrated by the inauguration of a kindergarten and a retirement home.

Oslo’s Jewish community centers around the Mosaiske Trossamfund, one of the two synagogues built in 1920. This Orthodox Ashkenazi synagogue offers daily services. It became quite active in the 1980s when Michael Melchior, the son of Rabbi Bent Melchior, became Oslo’s rabbi. In 1992, the Community celebrated its 100th anniversary.

The adjacent building houses the community center.

As part of the Norwegian government’s efforts to make reparations for the spoliation of Jews during the Holocaust, the community has been able to renovate its buildings.

The town is also known for being the site of the historic 1993 Oslo Accords between Israelis and Palestinians.

In 2006, with the help of restitutions made to the Jewish Community in compensation for the assets confiscated by the Nazis, the Norwegian Center for Holocaust and Minorities Studies was established. A permanent exhibition about the Holocaust is open to visitors. The Center is actually located in Quisling’s former villa.

The city also has a Jewish museum which is located in the building where another synagogue, built in 1921, used to be. The museum was officially inaugurated in 2008 by Haakon, the Crown Prince of Norway. The Museum holds three permanent exhibitions and offers pedagogic programs to schools in the region.

There are two Jewish cemeteries in Oslo. The ancient cemetery , in Sofienbergparken, dates from 1869 and was used until 1917. The new cemetery , in Helsfyr, has been in use since. Efforts have been made in recent years to preserve these sites, as well as the Holocaust memorial at Akershuskaia, outside the Akershus fortress.

Jews have lived in Göteborg since 1782. The Conservative (masorti) rite synagogue is located at the same address as the community center. There is also an Orthodox minyan in Göteborg.

Before settling in the city of Gothenburg in 1792, Jews were welcomed along with other minorities to the nearby island of Marstrand. Although the first synagogue was built in 1808, the presence of a rabbi did not materialize until 1837.

The current synagogue was built in 1855. It blends Moorish, Romanesque, and Byzantine styles inside, while outside you can see Scandinavian and Celtic designs.

The city’s Jewish population increased in the early part of the 20th century, with the arrival of Russian and Polish Jews fleeing pogroms and wars. Likewise during World War II with the arrival of Jews from Denmark, saved thanks to the courageous operation of the entire population and of the Danish authorities. Then also other Jews from Poland and Russia.

In 1968, Swedish Jews formed a community of nearly 1,500 people. Following Perestroika and the end of the Cold War, Jews from different countries forming the Soviet Union migrated to Sweden.

As in most other Swedish cities, Göteborg faces anti-Semitism propagated by neo-Nazi and Islamist circles. Thus, in 2017, the Göteborg synagogue was attacked with a Molotov cocktail. That same year, 600 neo-Nazis demonstrated on Yom Kippur.

The city also has a Jewish cemetery .

Danish Jews evacuated during the Nazi occupation arrived by boat in Malmö thanks to Count Folke Bernadotte. Some Jews died after their arrival and are buried in the city cemetery, where a monument honors their memory.

A Jewish community (originally made up of German Jews) was established in this city on the Baltic coast facing Copenhagen in 1871, shortly after the emancipation. It now numbers 1200 members. Its community center , partially financed from German reparations, was built in 1962. An Orthodox synagogue continues to function on the Föreningsgatan at the corner of the Betaniaplan. Built in 1903 in an eastern style, the synagogue is crowned by an onion dome reminiscent of Orthodox churches.

Malmö’s Jewish community carries out its activities in two suburban centers: the community center in Lund , which houses the Institute for Jewish Culture, is used only for holidays, while Helsingborg’s community center is always open. The Jewish community centers of Landskrona and Kristianstad, on the other hand, have been closed since the early 1990s. The interior decorations and furniture of Kristianstad’s synagogue are now being used by a Scandinavian community living in Raanana, Israel.

For the past 20 years or so, a wave of anti-Semitic attacks has reached Sweden, notably the city of Malmo, mainly due to neo-Nazi and Islamist movements. Whether it was attacks on Holocaust survivors, vandalism in cemeteries, or burning of places. An explosive was placed in front of the community center in 2012. Five years later, anti-Semitic slogans were uttered at a demonstration, and the chapel in the Jewish cemetery burned down. In 2020, during an Islamist demonstration, calls for the murder of Jews were made.

These particularly lofty acts in that city have forced Swedish Jews to leave it for Israel or other places where they feel more secure. The number of Jews has therefore declined sharply, by at least half, to less than 1,000 today.

In 2025, to mark the 250th anniversary of Malmö’s Jewish community, the city is organising a number of events in close cooperation with Malmö’s Jewish community. These include an exhibition devoted to Jewish heroines, which is on display in several municipal libraries.

The large university city of Uppsala does not have a Jewish community, but it does have a Jewish studies department.

When we think of Stockholm, we often envision the Viking past. Certainly, they are part of the history of the city, the country and the region. There’s even a Viking museum in Stockholm. But this city offers much more. For a start, its name means “a multitude of islets”: Stock (multitude) and holm (islet). And it’s on these 2 small central islets that you can start travelling back in time.

From Stockholm’s Royal Palace on Gamla Stan (“Old Town”) to the Museum of Modern Art and the Design Museum on Skeppsholmen. This style has and continues to influence our contemporary world, from buildings and department stores to ready-to-build furniture.

Not sure you’ll have time to visit all 24,000 islands. But a boat trip will let you discover a sample of them, whether by public transport or with the companies that organize such trips. So many different monuments await you. Whether it’s the beautiful cathedral, the Nobel Prize Museum, the Vasa Museum with its impressive 17th-century royal ship, the Nordic Museum… or the many green spaces, testimony to the care for the environment both on land and at sea.

There’s also a wide range of lifestyles, between the dark and cold of the North during the winter days, and the desire for colorful night-time celebrations. As can be seen in the stylistic distance between the highly calculated changing of the guard at the Royal Palace (a famous tourist attraction) and the Abba Museum, which takes us back to the atmosphere of the carefree years.

Not forgetting, of course, the city’s culinary specialties, especially fish, which you can savour at the Ostermalm market, bringing together tourists and locals alike.

Until 1775, Jews were banned from entering Sweden, unless they agreed to convert to Christianity. That year, an engraver named Aaron Isaac pleaded his case for living in Stockholm without converting. Long administrative procedures, from office to office, even led to a meeting with Gustav III, King of Sweden. The king granted this right. Thus began the official settlement of Jews in Sweden.

Twenty years later, the synagogue housed in today’s Jewish Museum welcomed the Jewish community. The synagogue remained in use until 1870, when the small space could no longer accommodate the growing Jewish community of around 1,000 families.

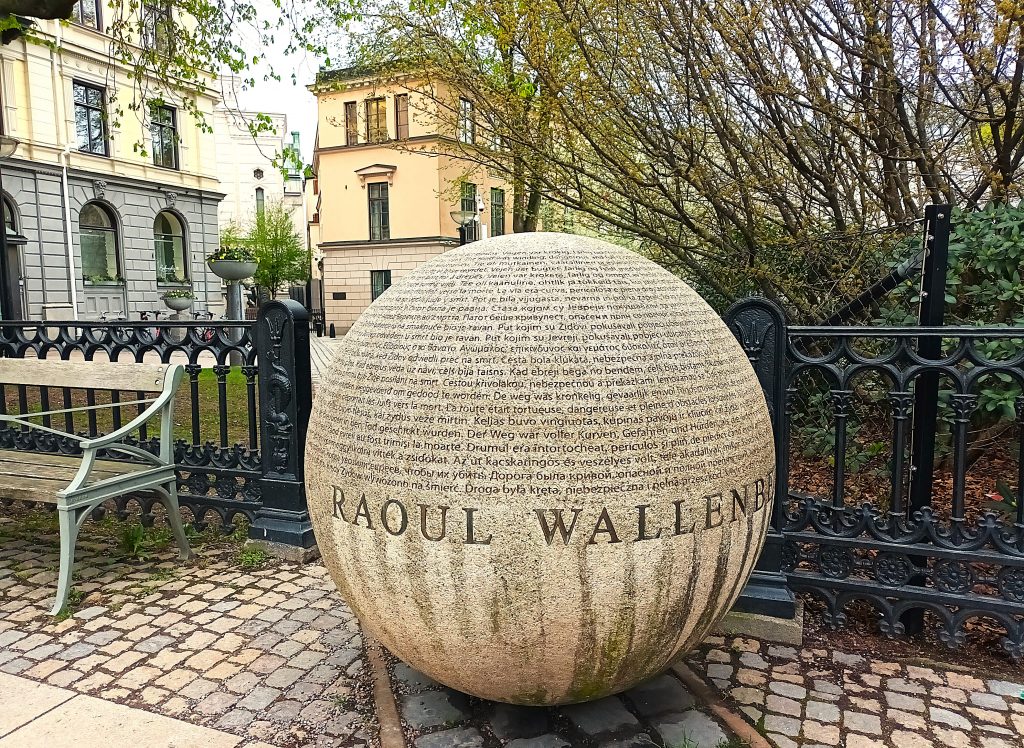

The Great Synagogue of Stockholm , which also serves as a community center, was built in 1870. It is located next to Raoul Wallenberg Square, named after the Swedish diplomat who rescued many Jews from Hungary and was arrested, then probably liquidated, by the Soviets.

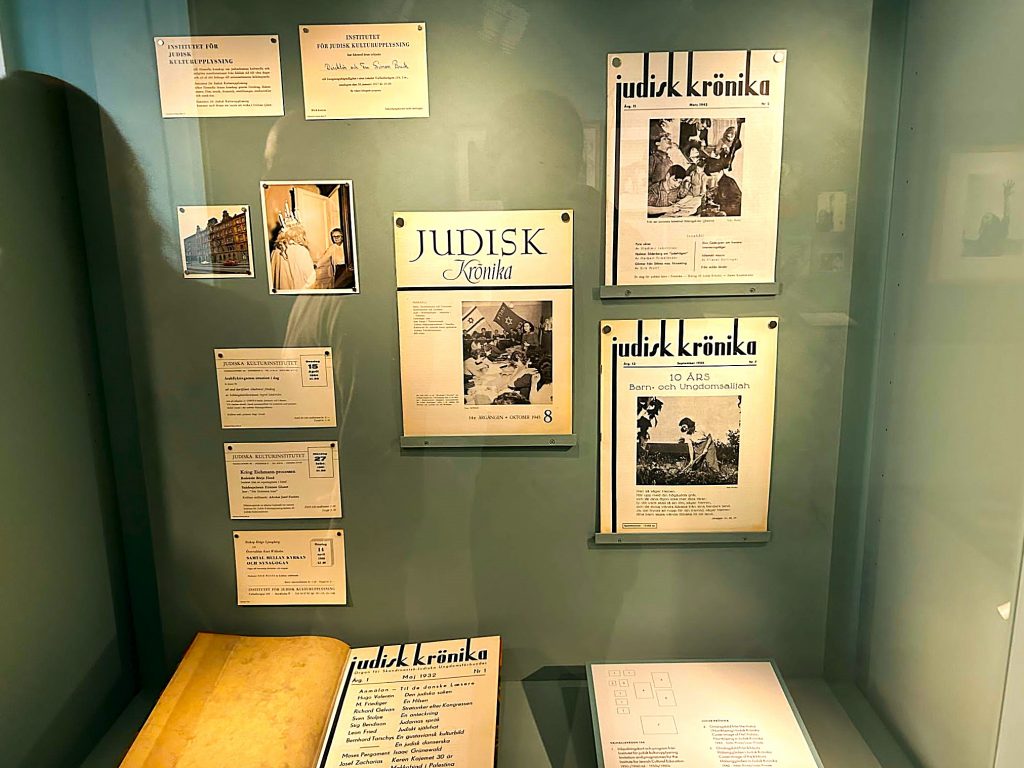

The oriental-style building can accommodate 1,000 worshippers following a massorti rite. In the synagogue’s community center, you’ll find a library whose main interest is the availability of the excellent magazine, Judisk Kronika, and historical works on Swedish Jews.

This modern Jewish community embraced the reforms underway in many Western European countries, as did others across the continent. Religious reforms were encouraged by the Enlightenment and the revolutionary spirit, but also by the national bond strengthened by the recognition of equal rights.

Sweden welcomed Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe at the end of the nineteenth century, fleeing pogroms. Living in the working-class districts of southern Stockholm, they established their own synagogue. Thus, Södermalm synagogue was built at the end of the 19th century. Jews from Eastern Europe worked mainly in textiles and commerce.

During the Holocaust, Sweden chose neutrality. A neutrality not necessarily appeasing to the Jewish community, which feared rapid geopolitical change. This fear was reinforced when, during the war, Swedish Nazi sympathizers began drawing up lists of Jewish compatriots to present in the event of a German invasion. Some Jews did not hesitate to buy weapons, just in case the situation evolved in this direction. On the other hand, let’s not forget that Sweden welcomed many Danish Jews who took refuge there during the formidable rescue operation.

Towards the end of the war, when it became clear that Germany was going to lose, Sweden adopted a more openly pro-Jewish policy. The country opened its doors to Jewish refugees and survivors, welcoming almost 10,000 people in 1945. As a result, Sweden’s Jewish population tripled in one year. Half of these new arrivals eventually chose to settle in Israel or the United States, but the other half preferred to stay on, enjoying the gentle Swedish lifestyle.

A memorial to the victims of the Holocaust was erected in Stockholm in 1998. It was designed by sculptor Sivert Lindblom and architect Gabriel Herdevall. It was inaugurated by Sweden’s King Carl XVI Gustav. It is composed of 8,500 stone tablets.

Today, there are several other Swedish synagogues. The Adat Yeshurun Orthodox synagogue contains furniture from a Hamburg synagogue vandalized during Kristallnacht. The other Polish-rite Orthodox synagogue, Adat Yisrael , is located in the Södermalm district, in a 17th-century building.

There are several Jewish cemeteries in Stockholm. The first was built by Aaron Isaac in 1776. It bears his name, Aronsberg . In use until 1888, it contains almost 300 headstones. The Kronoberg Jewish cemetery was built in 1787. It housed 200 graves until 1857.

As both cemeteries were very small, the Jewish community acquired additional land. In Solna, architect Fredrik Wilhelm Scholander built the chapel and gates of the Northern Jewish Cemetery . In 1857, the so-called “Mosaic Cemetery in the North Cemetery” was inaugurated. Scholander was also the architect of Stockholm’s Great Synagogue. Among those buried here is Nobel Prize winner Nelly Sachs.

The Southern Jewish Cemetery was built in 1952. Its chapel was designed in 1969 by architect Sven Ivar Lind. Nowadays, most burials take place there.

The Jewish Museum of Sweden

The museum was founded in 1987 by Aron Neuman, a patron of the arts, then closed due to a move to the Gamla Stan (“Old Town”) district, in the country’s oldest preserved synagogue. Apart from the structure itself, which is still easily identifiable, the museum still possesses a few elements of the old synagogue, including the aron and the bimah.

When the synagogue moved in 1870, the Jewish community sold the building to a priest, and it was transformed into a chapel. Over time, the building changed function, becoming a police station and then an architect’s office. It wasn’t until 2019 that the Jewish Museum of Sweden opened its doors, leasing the space from the city. Renovations were carried out, but with an eye to preserving the synagogue’s original setting. Some walls were repainted white, and layers of paint were removed elsewhere to reveal old paintings that had once stood there. These paintings are among the few remaining today in the North German style. Most synagogues decorated in this style were destroyed during the Holocaust.

The museum’s permanent exhibition recounts the contemporary history of the Jews in this country, which began in 1775. It shows the settlement of the first Jewish community, with its leading figures.

Then, gradually, the arrival of Eastern European Jews in the nineteenth century. A collection of clothes hangers symbolizes the arrival of this population, who worked mainly in the textile industry and created some of the biggest local brands, as can be seen on the labels on the hangers.

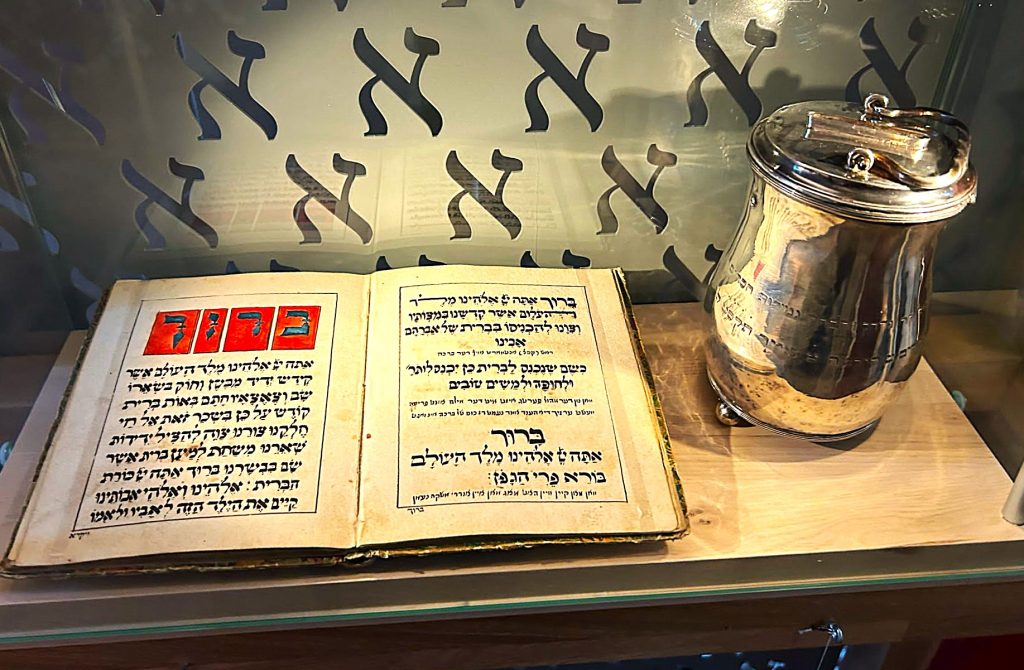

One area of the museum is dedicated to the persecution of Jews during the Holocaust. On display is a passport bearing the “J” stamp, which was required for entry into both Sweden and Switzerland, neutral countries during the war. They asked the German authorities to stamp passports in this way in order to deny Jews access to their territory. Preserved Jewish ritual objects from other European communities are also on display.

The museum’s permanent exhibition ends on a more positive note, presenting the development of contemporary Jewish life in Sweden. It highlights the reception of newcomer refugees, survivors of the Holocaust, and their contributions to the evolution of Swedish Jewish life. With some objects reminiscent of that era, notably those used for kiddush. And other ancient objects, including the small metal boxes found in many homes, collecting donations for the KKL and other institutions of the reborn state of Israel.

Among the new items acquired by the museum is an film recounting the settlement of Jewish Holocaust survivors in the small town of Boras. They settled there to work in the textile factories, helped by Jewish industrialists from Stockholm. Sweden’s rural exodus and the disappearance of many factories meant the end of many small communities, including this one, which is why this film and other objects in the Swedish Jewish Museum are so precious.

What used to be the balcony, where the women sat in the synagogue, is now home to small temporary exhibitions. These focus on Jewish rituals. In 2025, for example, religious headgears are on display, with both ancient and modern photos. Original items include kippot with a horse, a beloved Swedish symbol.

Major renovations were undertaken at the museum in 2024. The entire first floor was refurbished. The museum’s administrative staff left the first floor, in order to devote these spaces to temporary exhibitions, reserved for more contemporary subjects.

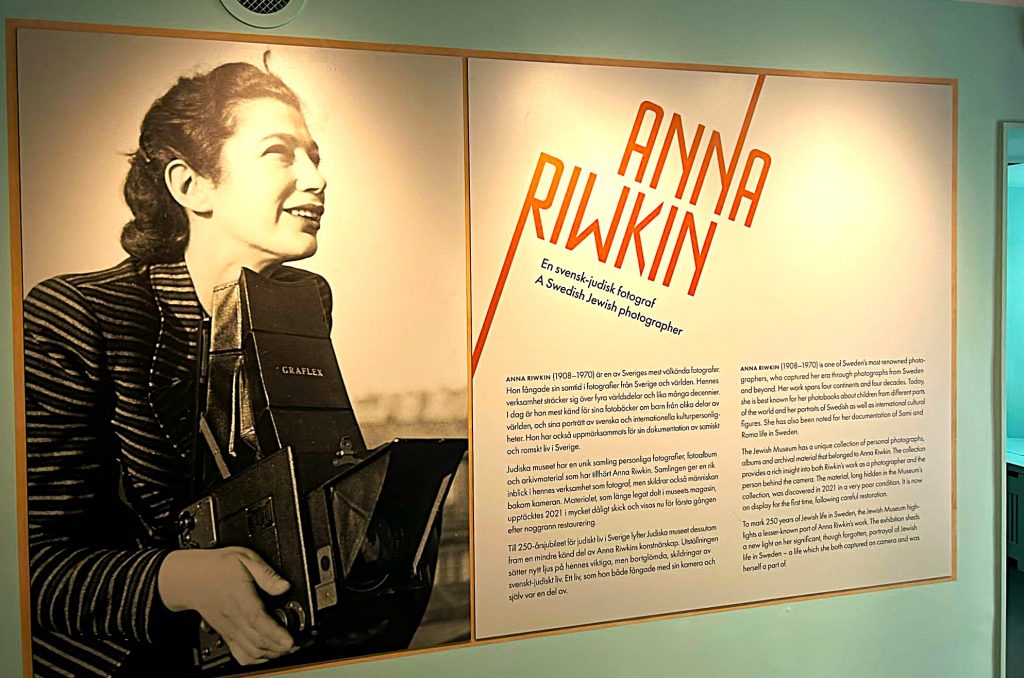

In 2025, the museum hosted a magnificent temporary exhibition dedicated to Sweden’s most famous photographer, Anna Riwkin (1908-1970). She is best known worldwide for her books dedicated to young people.

The exhibition features not only photos, but also numerous personal objects and writings. These include her diary, wedding album and portraits of her family taken when Anna was a teenager.

Born in Russia in 1908, she emigrated to Sweden with her family at the age of 7. Unlike the majority of Eastern European migrants at the time, her family was not very religious, but was very involved in the Zionist movement. Anna and her siblings found happiness in artistic practice, devoting their lives to it: author, translator, painter and photographer… None of them had children, except for their work.

At the age of 20, Anna Riwkin married Daniel Brick, one of the leading figures in Swedish Jewish life. In 1932, this journalist, publisher and committed intellectual founded Judisk Krönika, the Swedish equivalent of the Jewish Chronicle, a publication that still exists today. In this exhibition, you can see the letters they wrote to each other.

Throughout her career, Anna Riwkin took photos for various publications. She was known for her dance photos, portraits and advertisements. These constituted the first phase of her career, the second being devoted to reportage. From the 1930s onwards, she travelled all over Sweden and the world, photographing a whole host of people. As a result, she became a leading reference for the documentary presentation of Sami and Roma life. Anna was also the first to present a non-exotic image of these populations. Children feature prominently in her photos. Anna declared in an interview that, having been unable to have children of her own, the portraits of all these children helped to compensate for this pain.

She spent a lot of time abroad. The result was the annual publication of two collections of photos dedicated to these countries, one for adults and one for children. The photos were accompanied by texts written by Swedish authors. These books met with great success.

Less well known to the general public, however, and exhibited here, is Riwkin’s commitment to the presentation of Swedish Jewish life. So much so, that for four decades, from the 1920s to the 1950s, she was its principal documentarian. This involved a variety of projects, both personal and commissioned by community bodies. And, of course, photographs for the Judisk Krönika, run by her husband.

The exhibition features many moving photos from the first half of the 20th century: the arrival of Jewish refugees in Sweden, portraits, and the façade of the former synagogue that became this museum. Her commitment to Jewish culture was not limited to his talent as a photographer. Daniel Brick assisted her in founding the Institute for Jewish Cultures in Sweden.

The exhibition closes with her abundant photographs taken in Israel in the 1940s, before and just after the creation of the state. Anna Riwkin did not limit herself either geographically or culturally, crossing the country from end to end. Capturing images of its diverse population: men, women and children from different cultures, religions and living quarters. She published collections based on these photos, with texts written by Daniel Brick. Both books can still be found in the homes of Swedish Jewish families today. For decades, she was recognized as the leading photographer of Israeli life, her photos becoming a worldwide reference on the subject.

Swedish Museum of the Holocaust

The museum is housed in a building near the railway station. Two exhibitions are presented in the left and right sections of the Swedish Museum of the Holocaust . Opposite the entrance is a small room showing videos of Holocaust survivors answering various questions. Depending on the themes requested by visitors, the computer presents these videos, recorded earlier. A very contemporary form of memory sharing.

The 2025 temporary exhibition on the left-hand side of the museum looks at how the Swedish press dealt with the advent of Nazism and the Holocaust. The exhibition features many newspaper covers and newsreels shown in cinemas.

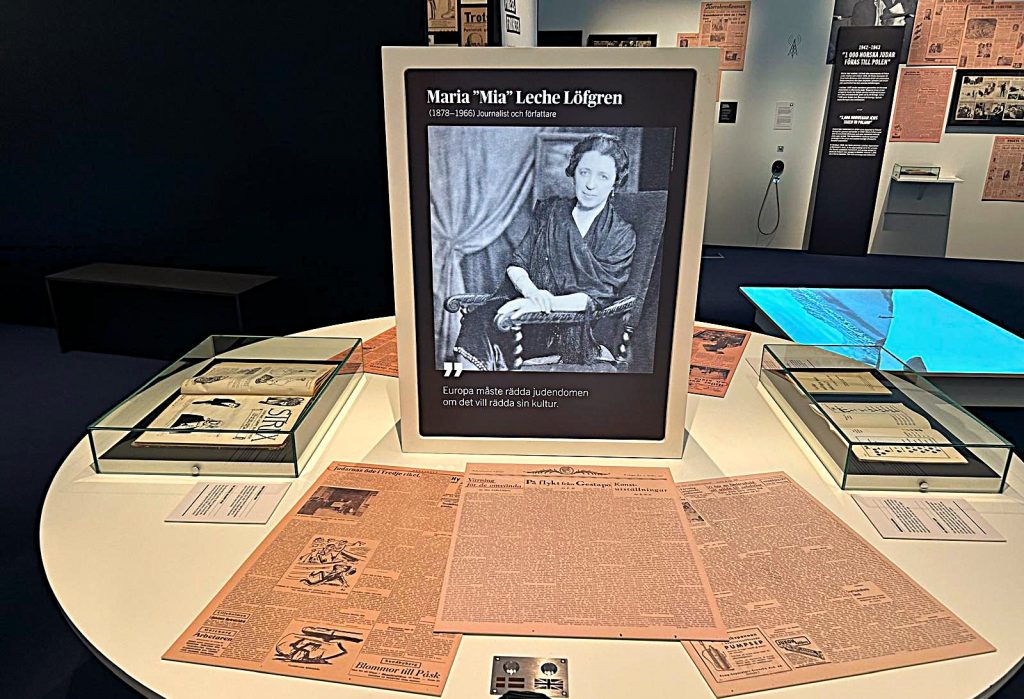

While some Swedish newspapers were coy in their presentation of the advent of Nazism, or chose pastel words to describe the murders, most condemned the Nazis’ policies. The latter did, however, have some allies in the press. You can, for example, discover the story of journalist Maria Leche Löfgren, who was one of the greatest campaigners for the diffusion of information on the fate of the Jews.

Also of interest are old newspapers from before the Second World War, attacking Jews. With the same far-right or far-left caricatures found in other European countries at the time, and now back in fashion: the Jews being accused of being a deicidal people by the former, or of conquering the world by the latter, or even, as some claim today, both at the same time.

The signs explain that the Swedish government put pressure on the press not to reveal too much about the fate of the Jewish deportees. They also mention that when the Germans began deporting Jews from Norway in 1942, many Swedes signed up to defend the Jews. And that the country welcomed Danish Jewish refugees, not forgetting of course the courage of Raoul Wallenberg. Among the anti-Nazi portraits, we discover the story of Amelie Posse (1884-1957).

As in many contemporary exhibitions devoted to the Holocaust, much space is given to the testimonies of the last survivors and the Righteous and their families who saved Jews during the war. The museum also pays homage to authors, journalists, politicians and other individuals who had the courage to oppose Nazism.

The temporary 2025 exhibition on the right-hand side of the museum is dedicated to Roma victims of the Holocaust. It shows the stages leading up to their deportation in Europe. It also pays tribute to their uprising in a concentration camp when the Roma rebelled, following a Polish political prisoner’s warning of their planned fate.

The exhibition tells the story of many families: men, women and children… how they were arrested and what happened to them afterwards. Who survived and who perished during the Holocaust. The exhibition also looks at how the Roma were discriminated against in Sweden for a long time. And how long it took the authorities to recognize this fact.

Among the moving stories told is that of Rose-Marie. A survivor of the Holocaust with her mother who suffered from numerous health problems and had no choice but to put the 5-year-old in an orphanage for two years. At school, Rose-Marie was bullied by many pupils who couldn’t understand why she had a number tattooed on her arm. The children thought it was a prisoner’s number. At the age of 18, Rose-Marie had the number removed from her arm. In 1952, she managed to trace her father in Germany, who had survived 7 years of captivity in Russia. The family was finally reunited.

Suomenlinna , a fortress island opposite Helsinki, was the site of the first Jewish place of worship. According to legal developments, a decree from 1869 and the letter from the Senate from 1876, demobilised soldiers were allowed to work in the civilian sector.

The city of Helsinki decided to donate a plot of land to the Jewish community in 1900 in order to build a synagogue. It is located on Malminkatu Street. A neighborhood where many of the city’s Jews lived at the time, who settled around the market where they could sell second-hand clothes, one of the only professional activities allowed in the 19th century.

In the 1880s and 1890s, most Jews worked in the sale of clothes and fruit at the narinkka market. In 1870, the Narinkka market moved to Simo (meaning Simeon) Square. This market is located in the Kamppi district, which also housed the synagogue in 1906. Before there was an official synagogue, prayers were held in the Viapori Beth Midrash in the 1830s and forty years later in the Villa Langen. The Narinkka Market closed down in 1931.

The Helsinki Synagogue , famous for its Byzantine-style dome, was built by architect Jac Ahrenberg in 1906. Twenty years later it was extended. Since then, it can accommodate up to 600 people, seated around the bimah, which occupies the center and above which there is a magnificent chandelier. Built on three floors, the synagogue’s architectural style is similar to that of most synagogues of the time, with symmetrical windows in the center. And on the sides, three small round windows with a maguen david in each one.

In the years 1920-1930, the National Library of Finland hosted many works in Yiddish published during the last decades of the Russian Empire. The community also offered many theatrical performances in Yiddish at the time.

Makkabi Helsinki

In 1906, a group of young people from Helsinki founded the Makkabi Helsinki sports association, the oldest Jewish sports club in the world still in existence, with an unbroken history.

The club took part in the 1st division football competition in 1930, then at lower levels. Today, the main sports are bowling, futsal, basketball and floorball. The club celebrated its centenary in November 2006.

Elias Katz is the most famous athlete to have represented the club. Katz won gold at the 1924 Paris Olympics with Paavo Nurmi and Ville Ritola in the 3,000 metres team race. He began training at Turku’s main sports club, where he befriended the legendary Finnish runner Paavo Nurmi, who helped him improve his technique. In December 1947, as civil war raged in Mandatory Palestine, Katz screened a film in a British military camp in the Gaza region. Later that evening, he was killed by Palestinian sniper fire.

In 1967, a community center was built adjacent to the synagogue. It was made available to allow a Jewish life for the members of the community. Among these services are a Jewish school, classrooms and conference rooms, an auditorium, a retirement home, and a mikvah. The community center also includes a Jewish library of 5,000 volumes. A copper Torah sefer ornament can be seen there from the city’s first synagogue, built of wood in 1840.

The center houses the Hazamir choir (founded in 1917), which has already performed at the Finnish Cultural Center in Paris, the bi-monthly magazine Ha-Kehila and all Jewish organizations in Finland.

The city has two Jewish cemeteries located in the place of the city gathering most of the graves. An ancient cemetery built in the 1840s and a new cemetery in 1895. The first being closed and the second currently used by the Jews of Finland.

Today, the Helsinki Synagogue regularly hosts a few dozen worshipers during ceremonies and prepares vegetarian meals for Shabbat celebrated there. Most of the Jews in Finland are vegetarians. The synagogue is Orthodox, although most of the Jews in Helsinki are less observant. Morning prayers are celebrated in a small hall of the synagogue.

The few dozen members of the liberal movement have no place of worship and are attached to the liberal community in Copenhagen. Yiddish is experiencing a revival in Helsinki, in particular thanks to the international meetings of Limud (written Limmud in English).

In 2025, there are 900 Jews living in Helsinki. Despite this relatively small number, many cultural events are organised and the synagogue now houses a café on the ground floor of the building.

The only glatt kosher hotel in Scandinavia, the Strand Hotel is located in the well-known spa town of Hornbaek. It operates between Passover and Rosh Hashanah and has a synagogue on the premises.

The Jewish community of Copenhagen has been active since the end of the 17th century. Today, most of Denmark’s 7,000 Jews live in Copenhagen. Abraham Salomon of Rausnitz was its first rabbi, appointed in 1687. Six years later, a Jewish cemetery was established in Mollegade.

Destroyed by a fire in 1795, no synagogue was active until a liberal one was built in 1833 in Krystalgade. Years later, orthodox and Sephardic places of worship were also opened.

The Royal Decree issued in 1814 gave Jews born in Denmark the same rights as all other citizens. Philanthropic institutions, schools, and old age homes have been opened since 1825. The number and presence varied then, according to historical events, especially the Holocaust.

When the huge majority of the Danish Jews and their relatives, about 8,000 persons, were saved by the courageous acts of Denmark’s royal, political and religious authorities as well as every level of society.

Most of the 3,000 Polish Jews who fled to Denmark during the 1970s settled in Copenhagen. Marking the continuous blossoming of the Jewish community in Denmark, Queen Margrethe II attended in 1983 the service in Copenhagen’s synagogue, celebrating its 150th anniversary.

The following year, she participated in the celebrations of the Jewish community’s 300th anniversary in Copenhagen. In 1993, the Queen also participated in the events celebrating the 50th anniversary of the country’s rescue operation.

In February 2015, a terrorist attacked the synagogue in Copenhagen, injuring two police officers and murdering Dan Uzan, who was guarding the venue where a bat mitzvah was taking place.

Its famous Great synagogue of Krystalgade was built in 1833 by the architect Gustav Friedrich Hetsch. It is defined by an architecture centering on an ark, influenced by Greek and Roman models.

The synagogue can welcome 900 worshippers. The community center is located next to the synagogue. All information about the synagogue is available at the Mosaiske Troessamfund, which houses a variety of Jewish associations. Mosaiske organizes visits of the synagogue from April to September and also provides Shabbat hospitality groups. An orthodox Community prays at the Makhzikei ha-Das Synagogue.

Among the social institutions, there’s a Jewish day school and an old age home. Religious and cultural organizations are also present in the city.

The Freedom Museum of Danish Resistance , which houses a important section devoted to the history of the Resistance movement and the Shoah. It was closed due to a fire on April 28, 2013. The damage caused was of such proportions that the museum had to be closed.

A new exhibition building was raised where it was located and reopened in 2020.

Designed by Daniel Libeskind, the Jewish Museum of Copenhagen presents Jewish life in Denmark through 400 years. The particular design of the Jewish Museum was influenced by the rescue operation during the Holocaust. The word “mitzvah” constitutes the emblem and concept of the museum. Therefore, the museum was designed around the courage demonstrated by the Danes.

It marks the positive experience which sums up Jewish life in Denmark and the special act of goodwill undertaken in 1943 by the population.

As explains architect Daniel Libeskind: “After entering the exhibition proper, the visitors are in a space constructed of a wooden floor with slightly sloping planes representing the four planes of discourse.

The entire exhibition space is illuminated by a luminous stained-glass window that is a microcosm of Mitzvah transforming light across the day. The Danish Jewish Museum will become a destination which will reveal the deep tradition and its future in the unprecedented space of Mitzvah.

The intertwining of the old structure of the vaulted brick space of the Royal Library and the unexpected connection to the unique exhibition space creates a dynamic dialogue between architecture of the past and of the future – the newness of the old and the agelessness of the new.”

The Royal Library contains the Simonsen Library which possesses an interesting Judaica section.

Digital facsimiles of the manuscripts acquired in 1931 from Professor David Simonsen are available for the public. Among the items which can be consulted, one can find a judeo-arabic letter from the 12th century and manuscripts from all periods since. Its most famous item is probably “Gemma’s prayerbook”, a Hebrew book written for the widow Gemma in Modena in 1531.

Documents came from 20 different countries, in 15 languages, which required some extensive handling of all those archives. And quite some time to ensure it would be handled in an apropriate manner. The total of the works constitutes about 26,000 processes of digitalization.

There are two Jewish cemeteries. The ancient one in the area of Mollegade, dating for four centuries. This cemetery can be accessed from April to September on Sundays, Mondays, Wednesdays and Thursdays. And the new cemetery in the area of Valby. The latter is open every day during daytime, except on Shabbat and Jewish holidays.

Interview with Janus Møller Jensen, Director of the Danish Jewish Museum

Jguideeurope : The museum made some major changes in 2022, what were the main ones?

Janus Møller Jensen: In September 2022, the museum reopened with a new main entrance and brand new exhibitions. The entrance was designed by Daniel Libeskind who, by this addition to the original architecture of the museum completed his work with an impressive and much more visible entrance to the museum. It also signaled a total relaunching of the museum with new exhibitions and a new way of presenting Danish Jewish history. We are in currently in a process of developing a permanent exhibition that will take the visitor on a journey through 400 years of Jewish life in Denmark. The guests will experience a first taste of this together with a strong special exhibition that focuses on the story of the escape and rescue of the Danish Jews in October 1943 in a wider context of the history of the 20th century.

Can you present to us three particular objects shown at the museum?

1. The story of the escape and rescue of almost all of the Danish Jews in October 1943 was the result of a common effort of the Danish population. But no one knew that it would a history of a rescue when the action against the Danish Jews was initiated the night between 1 and 2 October 1943. Some of the objects of the museum capture the personal drama of history. We have a life west that a mother sew for her daughter just before the escape across the Oresund to Sweden. It’s a very symbolic and strong object for the story of flight scenes doing what can be done to take measures to try and protect the children while fleeing. Some people actually lost their lives drowning during the escape.

2. Another strong object from the escape is the train ticket for the coastal train dated and stamped on 5 October 1943. Many Jews from Copenhagen sought by the help of others or on their own means t towards northern Sjælland to find transport across Øresund. The ticket is a return ticket bought, of course, to hide the fact that this was a one-way journey but at the same time symbolizing the hope of return that became a reality in May 1945, when Denmark was liberated by the allied forces from German occupation.

3. In the exhibition “Gateway to Denmark” that tells the story of the consolidation of Jewish life in Denmark in the eighteenth century and which is going to be part of the coming permanent exhibition of the museum, you find several precious objects. I must pick two: A prayer book and a challah cover. Both were produced in Denmark in the eighteenth century, and tells the story of both the establishment and the daily life of the small Jewish minority in Denmark through these beautiful objects across three centuries.

How is the courageous saving of the Jews during the Holocaust presented?

In several ways. First and foremost, in our spectacular architecture designed by Daniel Libeskind. Our entire room tells the story of the flight over sea and the uncertainty of trying to find one’s way. In many ways the unique architecture is one of the key objects of the museum. However, we also tell the story of the people that weren’t saved, and instead imprisoned in KZ-Theresienstadt. This story is currently the main theme of the special exhibition “Flight and persecution in the 20th century”.

Can you tell us about an encounter with a visitor or event participant which particularly moved you?

Talking to a visitor from America who had fled from Russia in the 1990’s, I was asked who so many Jews were saved. I replied they were naturally helped by neighbors. She looked me in the eyes and said “your neighbors don’t naturally help you; they are the ones that turn you in.” And indeed this also happened in Denmark. This conversation is a constant reminder of the need to balance the story telling of Denmark during the war. 99% survived Holocaust, but no flight is free, and war always has a price also for the survivors.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

Established in 1594 by the waywode Stanislaw Zolkiewski, Zolkiew was built, like other Polish cities, according to the Renaissance notion of the “ideal city” imported from Italy by theorist Pietro Cattanneo.

The city is laid out in orderly fashion around the vast rynek (central square), from where are visible the castle (in the seventeenth century the royal residence of the Polish king John Sobieski), the majestic Catholic cathedral, and the uniate church.

Only slightly hidden from view are the Zydowska Brama gate and the town’s magnificent seventeenth-century synagogue: financed by King John II Sobieski himself, it was designed by the royal architect Piotr Bebra and constructed between 1692 and 1700.

The remains of the Zolkiew Synagogue

The Zolkiew Synagogue, which escaped destruction by the Nazis despite their attempts to dynamite it, appears relatively well preserved from the outside, even if the stained-glass windows are broken and the roof damaged. The building’s future looks grim, however: in ruins in the middle of the city, it is not open to the public.

This Renaissance masterpiece was one of the most beautiful and largest synagogues in Poland and today is undeniably the most beautiful in all Ukraine. Its pink, painted facade, now somewhat discolored, is adorned with three gates in bas-relief delimiting three naves, while the roof is sculpted like a cathedral. Inside, only the heavy columns supporting the rood remain: the walls are bare and the floor is strewn with rubble. Though officially protected as a city landmark, since 1993 nothing has been done to preserve this magnificent yet endangered building.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

On the road from Lvov to Kiev, the most important city is Rivne, formerly a Polish city called Rovno, that was over 40% Jewish before the war.

It is worth a stop to see what remains of its Jewish quarter on Zamkowa Street; the spacious Wielka (Ancient) Synagogue at the street’s intersection with Skolna Street towered over the whole neighborhood (it has since been converted into a gymnasium). Beside it stands the even older Mala (Small) Synagogue, which is again active.

The Sosonki memorial

On the road to Kiev, around two miles from Rivne, stands the impressive Sosonki memorial. It occupies the spot where, on 6 November 1941, the 17500 inhabitants of Rovno’s ghetto were executed in a single day and left to rot in a huge, circular mass grave. Until 1998, this memorial with its tall marker could be easily seen from the road; the inscription reads “Sosonki” in Hebrew and Cyrillic letters. The inscription was defaced in 1998, and the monument also lost its most original feature: a line of metal characters seeming to sink into the earth. All that remains today are stelae surrounding the mass grave bearing the names of the dead in Yiddish.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism in its cultural, religious, and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

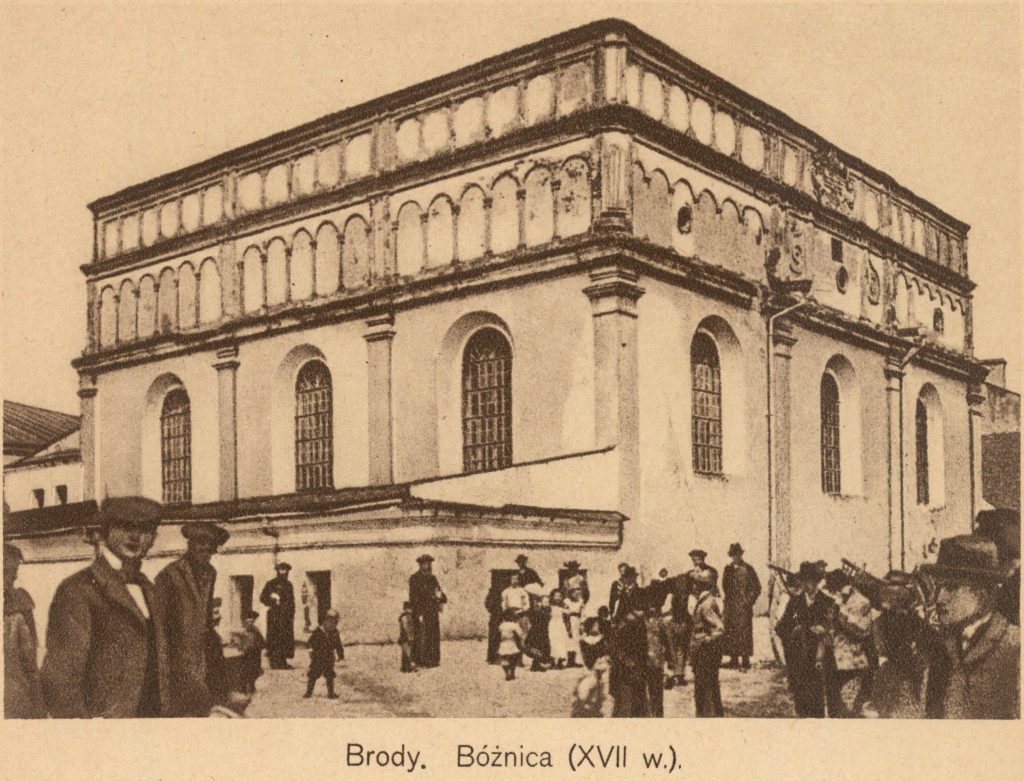

The city of Brody, founded in 1584 by Stanislaw Zolkiewski, started expanding in 1629 when the waywode Stanislaw Koniecpolski called on engineer and artillery captain Guillaume Levasseur de Beauplan to built fortifications and establish a zoning plan for the new city.

After Polish Galicia‘s annexation by Austria in 1772, for a hundred years (1779-1880) Brody was granted the status of “duty-free city” -exoneration from taxes. This benefit served to draw Jewish merchants and craftspeople here. By the nineteenth century, Jews made up 80% of Brody’s population.

Brody in literature

Balzac stopped here in September 1847 on his way to meet Mrs Hanska in Ukraine. He was supposed to spend a day and a night here before catching his coach, for no one worked in Brody on Rosh Hashana. “The Jews of Brody, despite the millions they could earn, wouldn’t leave their ceremonies behind” (Balzac, in a letter about Kiev).

Other writers have also mentioned Brody: Joseph Roth was born here in 1894 and evokes it in The Radetzky March (1932); Isaac Babel described the city in Red Cavalry (1933) and in his 1920 Diary.

The former Jewish quarter was demarcated by the streets named Sholem Aleichem, Evreiskaya, and Armianskaya, and today contains destroyed houses, Jewish-style courtyards, a defunct shop with the sign “Lustiger”, and other remnants of a bygone Jewish life.

The remains of a beautiful synagogue

The walls of the former seventeenth-century synagogue still stand on Szkolna Street, or Shulgas. It was one of the most beautiful in the region, comparable to that in Zolkiew. It is a fortified synagogue, its levels marked by small columns and adjacent structures on both sides.

The former Israelitische Realschule, located outside the central square, was a German-language school until the First World War; Joseph Roth once studied here. It is now a Ukrainian school. The immense, magnificent, and nearly intact Jewish cemetery is located at the northern edge of the city, just before the forest.

Holocaust memorial

It is a veritable open-air museum of graves bearing carefully carved designs, lions, stags, hands, candelabras. The inscriptions are almost always in Hebrew, but occasionally in German. No grave dates before 1941.

At the edge of the cemetery, in the forest, a monument commemorates the extermination of the Jews of Brody, either executed and buried in a common grave in July 1941 or deported to Belzec. Of the 12,000 Jews in Brody before the war, only one remains in Brody.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

Lvov -Lviv in Ukrainian, Lwów in Polish, Lemberg in German, Léopold in French- a city long Polish, then Austro-Hungarian, was again Polish between the wars. Annexed in 1939 by the Soviet Union after the German-Soviet nonaggression pact, it was occupied from 1941 to 1944 by Nazi Germany, taken back by the Soviets after the Second World War, and later reattached to Ukraine.

The Jewish community of Lvov was mentioned as far back as the thirteenth century, since, that is, the founding of the city. In the latter half of the fourteenth century, the city featured twi Jewish quarters, distinguishing Lvov from most other large European cities. The first, dating from 1352, was located “beyond the walls” around the Stary Rynek (Old Market) Square in the Kraków suburb (Krakowskie Przedmiejsce); the other, which dates from 1387, was located inside the city.

The old ghetto within the walls

The former ghetto stretched across the present-day Ruska, Straroevreiska, and Federova streets, near the Arsenal, southeast of the center of town. Today, you can see the remains of the Fedorovaolotaya Roza Gildene Roiz (Grand Synagogue of the Golden Rose) at the intersection of Straroevreiska and Federova streets.

Built in 1582, the synagogue was a late Gothic masterpiece with high lancet arches that towered over the entire quarter. It was of the most beautiful and oldest buildings in Lvov -until the Second World War. It owed its name to Rabbi Nahman’s wife, Rosa Jakubovna. Destroyed in 1941 by the Nazis, today there remains only the empty square, a few vestiges of the arches, and a commemorative plaque in English and Ukrainian.

The former ghetto beyond the walls

The former ghetto “beyond the walls” covered much larger area. This is where, north of the city center, Jews from Lvov settled throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. The quarter became, during the German occupation, a “ghetto” in that special sense the Nazis gave the term.

Behind the opera was located the Zydowska Brama (Jewish Gate), a few steps away from the Krakowska Brama (Kraków Gate), referred to as Vor der Shul (in front of the synagogue) by the Jews of Lvov.

The present-day Bogdan-Khmelnitsky Street turns into Zamarstynowska Street, the central street of the ghetto. Here, all the houses before the war were Jewish. On little Santa Street, formerly Boznicza (Synagogue Street) stood the suburb’s great synagogue and, a bit further down, the Hasidim Schul. The two sites are today empty lots. A plaque in English and Ukrainian was recently mounted on the wall of the former Hasidic synagogue; built in the seventeenth century it was reconstructed in the nineteenth century and destroyed in 1941.

The Hasidic synagogue

Only one temple can still be visited in this quarter, which once contained so many: the former Synagogue of Hasidic Innovators. Used for many years as a gymnasium, it was recently returned into the Jewish community and now contains the offices of the Sholem Aleichem Cultural Association . The association organizes meetings for the elderly and publishes the review Shofar.

To penetrate Lvov’s old Jewish quarter, stroll along the streets named Zamarsynowska, Muliarska, Balabana, Kulisha, and along the northern perimeter of the city. Beyond the railroad bridge on Chernovola Street (previously 700 Years of Lvov) stands a 1991 monument in memory of the massacre of 136800 Jews in Lvov, either exterminated in the ghetto or deported between 1941 and 1943.

On the footprints of Sholem Aleichem

Another possible exploration of the ghetto begins on the other side of Gorodecka Street, in the shadow of the opera. A stroll down Szpitalna Street is like being slowly transported into the world of the former shtetlach. Although the street is no longer Jewish, it has preserved its look of yesteryear, with its market crisscrossed by merchants carrying clothes and other objects in their arms.

At the intersection the street forms with Kotliarska Street, a plaque indicates the house where the writer Sholem Aleichem lived in 1906. Further down, the street opens onto a lively square where the streets named Rappaport, Sholem Aleichem, and Bazama converge: this was one of the nerve centers of the ghetto near the former Kraków market (Krakowski Rynek), today the “bazaar”. On Rappaport Street stands the former Jewish hospital, a large, Moorish building with an eastern-style dome.

Traces of Polish lettering can still be made out, “Izraelicki Szpital”, while Hebrew characters covered over with a Cyrillic inscription still read “Maternity Ward number 3”. The maternity ward’s garden is bordered by a plot that was in fact Lvov’s old Jewish cemetery. Dating back to the fourteenth century, its richness can be glimpsed in old photos. It has been totally razed and replaced by an extension of the bazaar.

A beautiful building on Sholem Aleichem Street features a monumental entrance resembling Paris’s Gare d’Orsay: formerly the Jewish consistory, with the rabbinical tribunal, this structure now houses the B’nai Brith “Leopolis” and the Lvov Center for Jewish Studies.

The Janowska camp

You will next arrive at Shevchenko Street, better known by historians of the Shoah by its former name of Janowska. A veritable concentration camp within the ghetto, the sinister Janowska camp was located on this street. It stood on the spot where currently there are barracks. At the end of the street is the Janowski cemetery , a section of which is Jewish. Almost all the graves date from after 1945, and thus are inscribed in Russian.

The only active synagogue in Lvov is located even further away, in the area of the train station on Brativ Mikhnovskikh Street, formerly Moskovskaya.

Lvov’s Jewish quarter also stretched south of Gorodecka Street and west of the Svoboda Prospect. A synagogue once stood on the streets called Nalivaiko and Grebinka, but it has since been razed. Across the street, Grebinka Street puppet theater (Teatr Lalok) was once the Jewish theater of Lvov. A little further down Bankovska Street, an empty space between two houses was the site of yet another synagogue.

A testimonial

In 1929, Albert Londres visited the eastern European Jewish communities and gave the following account of the Lvov ghetto: “The market lies at the heart of the ghetto. A pile of shacks like those built after an earthquake or a city burns down -a market? A field of manure, rather. You can choose from any garbage can in the Polish city!”

Albert Londres, The Wandering Jew Has Arrived. See also, The Jew Has Come Home, Trans. William Staples (New York: R. R. Smith, 1931).

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

Medzhibozh, in Podolia, has been a mythic city for Jewish communities ever since Israel ben Eliezer, better known today as Baal Shem Tov, settled there in 1740.

Israel ben Eliezer, the Baal Shem Tov

Israel ben Eliezer (1700-60), also known as Baal Shem Tov (Master of the Good Name) or Besht, was the founder of the Hasidic movement, which had a great influence in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries throughout the Jewish world of Ukraine and Poland. Eliezer’s preaching added a spiritual, popular, as well as festive dimension to Judaism. “One Simhat Torah evening, the Baal Shem himself danced together with his congregation. He took the scroll of the Torah in his hand and danced with it. Then he laid the scroll aside and danced without it. At this moment, one of his disciples who was intimately acquainted with his gestures, said to his companions: ‘Now our master has laid aside the visible, dimensional teachings, and has taken the spiritual teachings unto himself’.

Martin Buber, Tales of the Hasidim: The Early Masters, Trans. Olga Marx (New York: Schochen Books, 1947).

The medieval fortress

Medzhibozh, which means “between the Bugs”, is magnificently situated between two rivers bearing practically the same name: the southern Bug, a long river crossing all of Podolia to the Black Sea, and its tributary the Boujok (Little Bug).

Beside the river at the town’s entrance stands a large medieval fortress built between the fourteenth and seventeenth centuries but largely still intact. Before the war, more than 6000 residents, two-thirds of whom were Jewish, lived at the foot of this fortress. There remains, it is said, only one Jew today: the man who guards the cemetery.

The Baal Shem Tov cemetery

This cemetery is very old. The master’s grave is enclosed and protected in a small concrete structure containing prayer books and candles. Walking along the cemetery for about a half mile further, you will reach the new Jewish cemetery of Medzhibozh, whose graves date from the late nineteenth century to 1941.

This cemetery, much larger but less well-known than the old one, is quite beautiful as well. The graves are relatively well preserved, but the tombstones have already begun to sink, and a neighboring farmer has turned part of the cemetery into a farmyard.

The Holocaust victims

Further still, in a difficult to reach in the forest, is located the place where the Jews of Medzhibozh were executed. The mass grave has been covered with a huge concrete slab and a stele bearing the inscription: “Here, in these ravines, on 22 September 1941, the German Fascists barbarian cruelly gunned down more than 3000 women, children, and the elderly, prisoners of the Medzhibozh ghetto. In eternal memory of our compatriots”.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

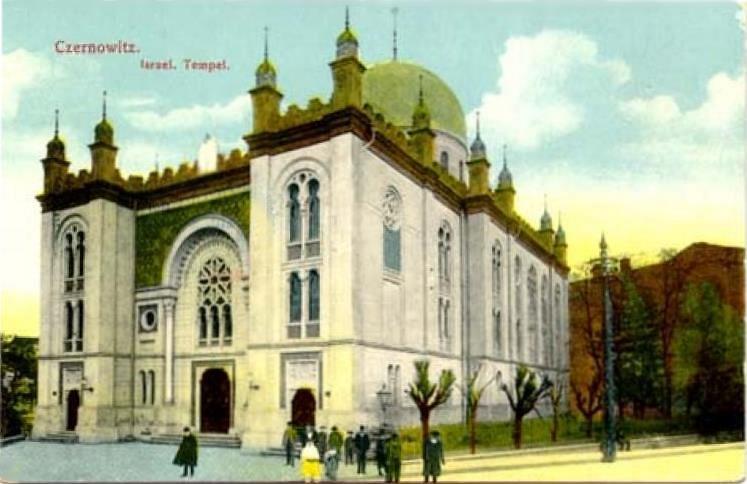

The former capital of Bukovina, the large German-influenced city of Chernivtsi (Czernowitz) once belonged to the Austrian Empire. It then became part of Romania during the wars, was annexed by the Soviet Union in 1940, and occupied by Germany and Romania from 1941 to 1944, only to become part of Ukraine after the war.

This once major Jewish hub (Jews made up around 40% of the population before the war) hosted the World Conference on Yiddish Language in 1908. It is also the birthplace of the Yiddish poet Itzik Manger, the fabulist Eliezer Steinbarg (who adapted into Yiddish the fables of La Fontaine, Aesop, and Krylov), the singer Sidi Tal, and the German-language poets Paul Celan and Rose Ausländer.

The magnificent city is well worth a visit. It retains its nineteenth and twentieth century Austrian feel, especially around its central square (formerly Ringplatz) and city hall, along Olga Kobylianska Street (formerly Herrengasse), Ivan Franko Street (formerly Rathausgasse), and Soborna Square (formerly Austria Platz).

Itinerary for a visit of Jewish life

A tour of the Jewish city begins at the former Grand Synagogue (or “Tempel”) located on Tempelgasse, today Universitetska Street. Though the Germans dynamited it, they failed to completely destroy it. The building functions today as a movie theater, Kinoteatr Chernivtsi ironically refer to as “Kinagoga”.

At Theatralna Square, the the right of the theater, stands the old House of Jewish Culture , transformed as of late into the Eliezer Steinbarg Cultural Association headquarters. Notice the monumental staircase and its Stars of David, their points sawn off since the Soviet era.

Steinbarg himself once lived on a neighboring street recently renamed in his honor, as pointed out by the plaque there. A door adorned with a Star of David can be seen just across the street.

Not far from here, at 16 Clara Zetkin Street stands the home of Mrs. Zuckermann, the ninety-two year old star of the film Mr. Zwilling and Mrs. Zuckermann (Volker Koepp: 1998). A victim of the Shoah, deported to Trans-Dniestria from 1941 to 1944, yet also an expert in the history of Chernivtsi, she once proudly declared: “I have remained Austrian; I love Czernowitz alone”.

Paul Celan

Paul Celan was born in 1920 at 5 Saxaganski Street (formerly Wassilkogasse). A plaque in Ukrainian and German marks the site. His parents perished after being transported to Trans-Dniestria. He moved to Paris after the war but continued to write in German, the “language of executioners”. His work, which grew more and more hermetic over time, deeply revitalized contemporary poetry. His most famous poem is Todesfuge (Fugue of Death):

“Black milk of daybreak we drink it at sundown

we drink at noon in the morning we drink it at night

we drink it and we drink it

we dig a grave in the breezes there one lies unconfined…”

From Poems of Paul Celan, Trans. Michael Hamburger (New York: Persea Books, 2002).

The active synagogue in town, located on Lukian-Kobylitsa Street, is very small, but the interior is beautiful, with mural depicting biblical themes.

Traces of the ghetto

Properly speaking, the Jewish quarter was located a bit further down, on the other side of Ruska Street. Transformed into a ghetto between 1941 and 1944, its entire Jewish population was deported to Trans-Dniestria. Take Turecka Street (“Turk”, after the former Turkish Fountain), and cross the bridge leading to the ghetto’s main street, Morariugasse, today Sagaidachny Street. The architecture of the block where Rose Ausländer was born has remained typically Jewish over the years. A wide street, it is bordered by a triangular public square formerly called Springbrunnenplatz where the market were held.

A right turn after the square leads to Henri Barbusse Street, formerly Synagogengasse, one of the poorest and most crowded streets of the ghetto. The former Grosse Schul (Big Synagogue) can be still be seen in the center at number 31; a very large building with a Greek pediment, it serves today as a “repair and production complex”. Further down, at number 18, a former prayer house features two Stars of David struck with the letter shin on the door.

One of the oldest synagogues

There was an inscription that read in Romanian and Hebrew “makhsike sabatul” (those respectful of the shabbat), but it was painted over in 1998. Chernivtsi’s oldest synagogue is located a little further up; it dates from the eighteenth century. A Hebrew inscription once read “Hevra Tehilim” (brotherhood of psalms), but this also disappeared in 1998. Donated to the Protestant community, the synagogue has been renovated, its main room divided into two levels and a facade (where the inscription was located) repainted.

Further still, at the spot where Henri Barbusse Street converges with Sagaidatchny Street, the Jewish hospital, now neglected, can still be seen through a locked gate. A commemorative plaque mounted on a house off the square points out, in Ukrainian and Yiddish, that the ghetto was once located on this street until its 40,000 residents were deported.

The Jewish cemetery is both impressive and fairly well maintained. The inscriptions on the tombstones are mostly in German, though a few are in Hebrew or Russian.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

The city of Uman is most famous for the Sophievka, a park built by Count Potocki in the grand style typical of eighteenth-century landscape architecture. It is also where Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav (Brasov), a great-grandson of Baal Shem Tov and continuer of his doctrine, settled and later died in 1810.

A city of pilgrimage

Only one grave remains from the old Jewish cemetery: that of Rabbi Nahman, a holy shrine today. A synagogue has been built beside the gravesite itself, allowing for reflection both indoors and out.

A number of pews have been installed, as well as a railed footbridge designed to keep the faithful in line before they enter the prayer room. The cemetery entrance is protected by a guard, where an inscription in French, English, Russian, and Hebrew reminds visitors that they are in a holy place.

Behind Rabbi Nahman’s tomb stretches what used to be the cemetery, now merely a snow-covered field (in winter) surrounded by housing projects.

Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav (Brasov)

The tsaddik, author of tales and other literature, defender of a mystical sort of existentialism, chess player, theorist of instability, precursor to Kafka- Rabbi Nahman of Bratslav (1772-1810) was a man of extreme paradox.

He recast Hasidism in a new and profound light, giving birth to a movement that today boasts thousands of followers, especially in Israel and the United States. Every year in September, around the Jewish New Year, thousands of pilgrims visit Uman to pray and reflect at his grave.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism in its cultural, religious, and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

The city of Pereyaslav, to which the name Khmelnitsky was added in honor of that Cossack leader, was also the birthplace of Sholem Aleichem.

To lovers of musical comedy, the city is better known as Anatevka, the name it bears in Fiddler on the Roof. Aleichem found inspiration for his novels’ many characters here: the one who seeks their fortune, the boy who joins the revolution and is sent to Siberia, the girl who betrays her faith by marrying a Ukrainian, the mother who remains in the shtetl with her children while the father plays the market in Odessa and Yehupets, etc. Today, Pereyaslav has retained a cartain charm, even if the city has lost its Jewish community. The former Jewish quarter was located right downtown.

Sholem Aleichem

His real name, Sholem Rabinovitz, founder of classic Yiddish literature, Sholem Aleichem was born in Pereyaslav in 1853 and died in New York in 1916. The world of the shtetl and the everyday people who lived there are immortalized in his writings. His most famous work, Tevie the Milkman, was magnificently set to music as Fiddler on the Roof, or Anatevka, by Jerry Bock and featured the song “If I was a Rich Man”. His other well-known works include the 1892 Menahem Mendel.

The Grand Synagogue of Pereyaslav , which dates to the nineteenth century, is located across the main square behind city hall in a large, rectangular building named the House of Culture today. No plaque indicates the building’s previous purpose. On Saturday and Sunday afternoons, locals pack the stifling main room to sing Ukrainian folk songs. To the side, a section of the building had been converted into a café-disco.

To find Sholem Aleichem’s birth house , take Lenin Street to the intersection and turn right; a commemorative plaque to the left marks the site.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

Established in 1794, Odessa was captured by Admiral de Ribas from the Turks for Empress Catherine II of Russia. The city developed rapidly during the nineteenth century, largely due to the arrival of colonists from “New Russia”. It soon became a melting pot of Russians, French, Armenians, Poles, Greeks, Moldavians, and Jews. Forbidden to reside in Saint Petersburg, Moscow or Kiev, Jews poured into the southern Russian cities of Odessa and Nikolayev, eventually constituting a third of their population before the Second World War. Even today, Odessa still bears their mark.

A Jewish city

An Odessan was asked one day,

-How many people live in Odessa?

-One million.

-And how many of them are Jews?

-I just told you. One million.

You see, in people’s minds, “Odessan” and “Jews” are often confused.

Jewish Odessa began at the Greek Square (“Gretsk, that’s what they call the street where the Jews do business”, Sholem Aleichem wrote), Alexandrovski Prospect, the old marketplace, and the streets named Evreiskya, Bazamaya, and Malaya-Arnautskaya. It continued on the other side of Preobrajenska Street, down Tiraspolskaya to Staroportofrankovskaya streets, and beyond that to the neighborhood by the train station. It covered the entire Moldavanka suburb, where the famous Privoz market is found, and ended at the Slobodka district, where the deportation convoys waited during the German-Romanian occupation. The Jewish quarter encompassed a tremendous area, in other words, stretching from downtown all the way to the western and northern suburbs. Before the war, 350,000 Jews lived here. They number no more than 50,000 today.

Touring Jewish Odessa involves a great deal of footwork. You need to pace up and down the streets, stroll through the neighborhoods, enters and exit courtyards… At Privoz market , breathe in the smell of fresh vegetables, bitter herbs, almonds and raisins, and soak up the atmosphere of the Moldavanka, the children playing in the streets. As fancy suits you, stop by one or more of the few remaining synagogues, examine the various monuments and plaques, and pay a visit to the Slobodka cemetery.

Odessa, the birthplace of Klezmer music

Odessa was also the birthplace of Klezmer music. Blending clarinet, cello, and balalaika with Middle Eastern rhythms, klezmer is making a comeback in Europe after crossing the Atlantic. In Odessa, the klezmer group Migdalor improvises from scores by Alexander Tcherner.

The synagogues of Odessa

Before the First World War, Odessa contained seven synagogues and forty-nine prayer houses. The oldest was the Brodskaya (Brody), or Choral, SYnagogue, built in 1840. With its four domes, it still towers over the intersection of Pushkin and Jukovysky streets, and archival warehouse today. The beautiful building has been given back to the Jewish community of the city and will be transformed back into a synagogue within a few years.

Only two synagogues are still in service: the Glavnaya (Main) Synagogue and the Hasidic Synagogue. There was also a Dockworkers’ Synagogue (near the port, now in ruins) and even a synagogue for kosher poultry shellers.