After Prague, until the nineteenth century the largest Jewish community in all the Czech lands lived in the city of Mikulov, south of Brno. Its yeshivoth were renowned throughout the region, even to Galicia.

The ghetto extended to the west of the old city around the present-day Husova and Zameskà streets, but only a few houses dating from the ghetto’s heyday still stand. In the nineteenth century, before the demolition of 1950-60, the Jewish quarter had some ten prayer halls and three synagogues.

Only one of Mikulov’s synagogues remain: the Ancient Synagogue , built in 1550 and destroyed by fire nearly two centuries later. It was reconstructed in 1723. The only Polish-style synagogue of its kind in the Czech Republic, it has four columns at the center of the large prayer hall surrounding the bimah. Some of the toms of this large city cemetery date to 1608. As in Prague, the grave markers in the oldest part of the cemetery are piled up in several layers. There are roughly 2500 tombstones here, some richly decorated. The entrance to the cemetery is on Hrbitovni Square.

Boskovice is located nineteen miles north of Brno. This large center of Jewish culture and study of the Torah was for many years the headquarters of the chief Rabbinate of Moravia.

The fifteenth-century Jewish quarter extends from the present-day Bilkova and Plackova Streets, near the large square. The original plan, with the ghetto gate always visible and the tiny streets lined with two-story houses, has remained almost completely intact despite the renovations and restorations undertaken in the nineteenth century.

The synagogue is on Traplova Street, in the heart of the former ghetto. The original seventeenth-century building was remodeled in the nineteenth century in a neo-Gothic style.

The cemetery is one of the largest in Moravia. There is a new (small) museum that can be visited. Every year, a music festival is held in the Jewish quarter.

The city of Trebíc is located thirty-one miles north of Brno on the other side of the Jihlava River. Its Jewish quarter, near the city center, was one of the largest in the country: in the middle of the nineteenth century, it counted more than a hundred houses. The quarter grew beginning in the sixteenth century, and even today many of its residences retain some traces of their Baroque or Renaissance origins.

The Old Synagogue , on Tiche Square west of the former ghetto, was erected in the eighteenth century on the remain of a very old wooden synagogue. Destroyed several times by fire, it was rebuilt in a neo-Gothic style and enlarged for the last time in the nineteenth century. After the war is became a place of worship for the Hussite Church.

The New Synagogue on Blahoslavova Street was probably also built on the remains of a wooden building dating from the eighteenth century. It was remodeled in 1845 and 1881. Now an exhibition and concert hall, it retains part of its interior decoration, most notably its stuccoed ceiling.

Although no trace remains of the former cemetery near the castle, it is possible to visit the large cemetery -with over 3000 gravestones- on Hradek Street not far from the Old Synagogue. The oldest stones date back to the beginning of the seventeenth century.

The lovely little garrison town of Terezín in the same region was created at the end of the eighteenth century during the reign of Joseph II.

In 1942, the Nazis totally emptied the city of its 7,000 inhabitants -with the exception of Jewish families- and transformed it into a ghetto and transit center for Czech Jews of the capital and surrounding lands.

Some 57,000 Jews were held in Terezín’s newly formed ghetto. As many as 152,000 deported Jews of fifty-three different nationalities passed through the town, including 74,000 Czechs. More than 30,000 of the imprisoned died in the ghetto. Approximately 87,000 departed from Terezín to the death camps, of which only 3,000 returned. A quarter of the ghetto’s inhabitants died of illness related to lack of hygiene and malnutrition.

Despite the terrible conditions and mass arrests, the prisoners succeeded in maintaining a minimum of organization and social life, with centers for study and prayers. Of the some 150,000 Jews who transited through Terezín, the 3,000 who stayed there several years received a basic education, in secret since schools were prohibited. The brightest stars of the Jewish-Czech intelligentsia were sent to this ghetto, including sculptors, painters, musicians, writers, and other intellectuals, whose presence was used as part of the Nazi propaganda machine. A delegation of the International Committee of the Red Cross was authorized to visit the ghetto in June 1944. When the camp was liberated on 8 May 1945 by the Red Army, 6,800 Jews were still in detention.

A memorial was erected in 1955 in the eastern part of the cemetery with text in Hebrew and Czech. Close to 13,000 persons -in 11,250 individual graves and 215 communal burial pits- were buried between 1941 and 1942 in the ghetto’s cemetery, beside the municipal cemetery. The crematorium constructed by the Nazis at the time has been transformed into an exhibition space. At the end of 1944, the ashes of the 22,000 victims were thrown into the nearby Ohre River. A small burial mound in memory of those who died has been erected on the riverbank.

On a hill above the city stands the Kleine Festung (small fortress). This former Austrian prison served as a Gestapo interrogation center where some 35,000, including a number of Resistance fighters, were questioned and imprisoned. The remains of 26,000 of these prisoners are buried in the national cemetery in front of the center. Since 1962, the town of Terezín and its fortress have been national museums.

In 2023, Finn Taylor made the very moving film Avenue of the Giants. A biopic on the life of Herbert Heller, who kept secret for 60 years his childhood spent in Terezin and then in the concentration camps, living the rest of his life in California and revealing his terrible childhood at the age of 74 in a process of tikun olam.

In 2024, the book Borrowed Time: Survivors of Nazi Terezin Remember was published, a collection of photographs by Dennis Carlyle Darling. In it, the American photographer brings together black and white portraits and testimonies of Jews who were imprisoned there.

The large village of Roudnice nad Labem twenty-five miles from Prague was one of the first small centers of Judaism in Bohemia and merits a brief visit. The oldest Jewish quarter, destroyed in the seventeenth century, stood beside the village’s lovely Baroque castle.

The “new ghetto” is to the west of the castle in what is today Havlickova Street. It contains ten or so homes, eventually sold to Christians. The quarter spread while remaining separated from the rest of the town by a barrier. The homes on the south side of Havlickova Street have maintained much of their appeal.

At one time, Roudnice nad Labem had three synagogues. Not a trace remains of the oldest synagogue. The second, erected in 1613 and remodeled in 1675, was destroyed at the end of the nineteenth century to make way for the train station. The third, to the north of Havlickova Street, was constructed in 1852 in a neo-Romanesque style and was in use until World War II. It now functions as a warehouse.

Three cemeteries also existed in Roudnice nad Labem. The ancient cemetery is the most moving of them, extending roughly 1200 feet from the existing synagogue. It contains interesting tombstones from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. A cemetery can also be visited.

Plzen is the principal center and beer capital of western Bohemia. The Jews were expelled from the city in 1504 and not permitted to return for more than two centuries. Following the industrial and urban development in the nineteenth century, a Jewish community resettled here and flourished. In 1921 more than 3000 Jews lived in Plzen.

Three synagogues were built in Plzen in the nineteenth century. The most interesting of the three stands to the west of the historic city center on Nejedleho Sady. Crowned by two towers, this magnificent neo-Romanesque building dates from 1890. No longer active, it is slated to become an exhibition space about Jewish life in Bohemia. A small prayer hall was established at 80 Smetanovu Sady, in 1988. There are two jewish cemeteries, an ancient cemetery and a new cemetery

The neighboring villages still have traces of the life of the small local Jewish communities, especially Radnice (approximately twelve miles northeast), which has a small Jewish quarter, an eighteenth-century synagogue (now a storage facility), and a small cemetery. Rokycany (about nine miles east of Plzen) also merits a visit.

The Great Synagogue in Plzen was reopened in 2022 following extensive restoration work. Initial restoration work took place in the 1990s, focusing on the exterior of the building. This time, it was the turn of the frescoes and the aron. The synagogue is now used as a concert hall and exhibition space.

There is a small Jewish quarter of about ten houses to the southwest of Kasejovice’s central square, linked to the rest of the city by a narrow, straight street.

The synagogue , in the heart of the Zidovske Mesto, was built in 1762 in the rococo style and redone a century later. With its striking aron and painted decorative features, it is one of the most interesting and best preserved in the region.

In Breznice in western Bohemia one can still see the former Jewish quarter created in 1570 by the local lord, Ferdinand of Loksany, and enlarged a century and a half later. The two streets and large square of the quarter are lined with low houses. Breznice’s Jewish quarter is located to the north of the town’s central square.

Its most beautiful building is the Popper Palace, a manor house with courtyard that belonged to the celebrated Jewish merchant and financier of the eighteenth century, Joachim von Popper, one of the first Jew in the Czech lands to receive a noble title.

The synagogue, constructed in 1725 and remodeled a century later, still exists and is located on the square of the former ghetto, although it is now used for storage. Despite the new building and road construction projects, the town’s small Jewish quarter preserves its original plan and architecture.

At the edge of the city on the way to the village of Predni Porící is a Jewish cemetery active until World War II that has some interesting Baroque-style tombs.

The small town of Golcuv Jenikov near Caslav had a significant Jewish quarter of some fifty homes to the south of the town’s central square. Most have kept their original appearance. Of interest is that Christian also lived in Golcuv Jenikov Jewish quarter.

The oriental neo-Romanesque synagogue was constructed in the middle of the nineteenth century.

The Jewish cemetery has some interesting Baroque tombs.

The nearby little town of Hermanuv-Mestec had a significant ghetto close to the current Havlickova Street. Its synagogue now serves as a warehouse, but the aron had been preserved.

Those with a healthy curiosity should make a quick detour to the small town of Cáslav, located forty-four miles southeast of the capital. Forbidden to Jews until the middle of the nineteenth century, the communities in the neighboring villages began to settle here after the Jews’ emancipation. To the northeast of the large square on Fucikova Street one can see an unusual synagogue in a neo-Moorish style with an odd rounded pediment and a beautiful painted-wood interior.

The synagogue , built in 1899, was designed by Viennese architect Wihelm Stiassny. The plan is a simple rectangle, with a west transept. The building is a singular example of the revival of the Moorish style in the 19th century. The synagogue was used as a depot during the Second World War, then as a municipal art gallery in the 1960s. In 1994, Cáslav City Council transferred ownership of the building to Prague’s Jewish community, following a campaign of claims for the restitution of looted Jewish property. As a result, the synagogue was renovated. Despite the deterioration of the building, certain original elements remained intact: the ceiling and decorations in the central nave, the columns and stuccoes, as well as certain elements of the exterior façade. Erosion was also threatening the building. Work is due to be completed by mid-2019, and the synagogue will become a municipal cultural centre.

Among the leading figures from Caslav is Milos Forman (1932-2018), a member of the Czech New Wave and director of such masterpieces as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest, Hair and Amadeus. Following the deportation and murder of his parents, he was raised by relatives. After completing his studies, he made his first films in the mid-1950s. When his film The Firemen’s Ball was banned by the authorities following the Soviet invasion in 1968, he emigrated to the United States.

The city of Kolín, one of the most important places of Jewish remembrance in the Czech lands, is worth a trip to see the small streets of the Jewish quarter and the magnificent cemetery. Overrun with vegetation, the cemetery’s atmosphere recalls that of Prague’s old Jewish cemetery before it became a usual stop for large tour groups.

The Jews settled in this town close to the Kutná Hora and its silver mines as early as the fourteenth century. Expelled and then allowed to return in the sixteenth century, the Jews’ homes stood in what was probably already the ghetto dating from the time they first settled in the city. The Jewish section was in the western corner of the city’s old walls near the large central square.

Zidovska ulicka (Street of the Jews), lined with small Baroque and classical houses, has been transformed into two streets, Na Hradbach and Zlata streets. You can still see the building housing the school and synagogue, constructed in 1642 and enlarged in the eighteenth century, with the addition of decorative stuccowork on the arches. The Baroque aron is also eighteenth century. Active until World War II, it is no longer in use. A small portion of its ornaments and religious objects are preserved in a synagogue in Colorado in the United States.

The ancient cemetery is accessible from Slunecni Street; the former main entrance on Kmochova Street is now closed. The cemetery was enlarged several times during its history until its closure in 1887, and it contains more than 2600 gravestones. The oldest graves date from the beginning of the fifteenth century. The new Jewish cemetery, which is at the edge of the city in the neighborhood of Zálabí, is not particularly interesting.

In the village of Drevikov, roughly sixty miles southeast of Prague, it is possible to see how Jews lived in the villages of Bohemia at the end of the nineteenth century, before their immigration to cities and industrial centers. About thirty Jewish families lived in the two-story houses on the “Jewish street” of this village.

The school and small synagogue of the community, now a store, can still be seen. The cemetery is nearby at the edge of a wood. The Jewish houses, partly of wood, the small synagogue, and the mikvah are to the village’s south.

Velká Bukovina, further away, is another rural ghetto that is well preserved.

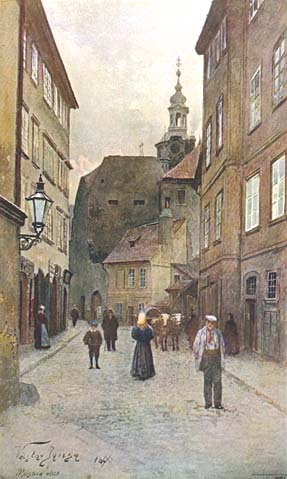

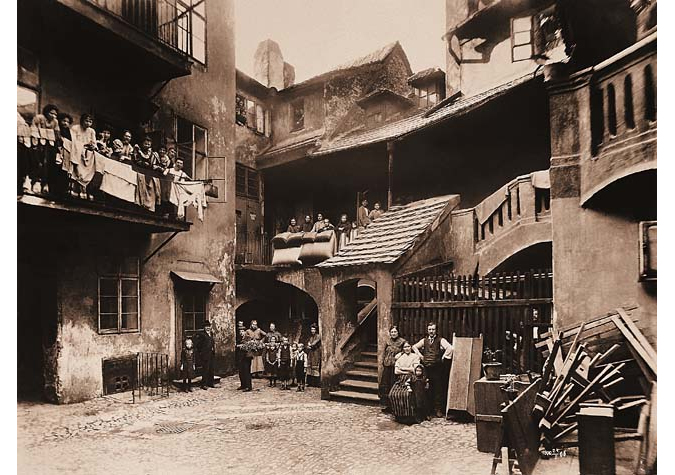

Stuccoed in pink, green or yellow, grand neo-Renaissance and neo-Gothic buildings line the Parizká, the Avenue of Paris. Since the fall of the wall, elegant boutiques have been flourishing on this major traffic artery, which lacks none of the cachet that it had at the beginning of the century. Here the legendary ghetto of Prague was located until the renovation of the city center between 1897 and 1905.

All that remains are the shadowy alleys abandoned by the growing number of Jews at the time of their emancipation in 1850. Only the poorest and most pious stayed in the former Jewish quarter, “with its shelves of old clothes, scrap metals, and other nameless things on display”, as Apollinaire wrote in Le Passant de Prague (The Wandering Jew). It is the smallest district of old Prague, covering an area scarcely 86,000 square feet, and there is not a single tree except for those in the old cemetery. Deserted by its former inhabitants, these small, dirty islands of residential space were gradually invaded by the poor, the marginalized, and the city’s prostitues.

In the first years of the twentieth century, the bordellos with their red lanterns and the disreputable taverns multiplied among the places of worship and buildings still inhabited by Orthodox Jews. On Shabbat evenings, the prayers and sacred songs of the Jews mingled with the blaring music of the gambling houses. This universe has disappeared. It survives only on the main synagogues, now museums, which stand only steps away from the grand, straight avenues born of modern urban planning. In the past, these synagogues, with their mysterious, otherworldly facades, stood out among the sordid hovels that seemed ready to overwhelm them. Not long after the demolition of the ghetto, the poet Jaroslav Vrchlicky wrote, “You are like widows, gray synagogues/ Clothing torn and head covered with ashes/ But when night with her black tallit descends on earth/ I see your windows shine with candlelight and scarlet”. The ghetto was razed, but its memory lives on, as Franz Kafka recalled in his conversations with Gustav Janouch.

Since 2024, a street in Prague has been named after Nicholas Winton (1909-2015), the British businessman who saved 669 children during the Holocaust by chartering a train to take them to London. Some of these children, still alive today, took part in the nomination ceremony, which was attended by the Mayor of Prague. The ceremony took place on the 85th anniversary of the last Kindertransport from Prague, which was prevented from leaving by the occupying authorities. The film One Life (2023) by James Hawes, starring Anthony Hopkins as Nicholas Winton, pays tribute to this man’s courage. The story only became public knowledge in 1988 when TV presenter Esther Rantzen paid tribute to him on That’s Life by inviting Nicholas Winton into the audience and surprising her by inviting the children he had saved.

Impressions of the ghetto

“The picturesque aspect of the Ghetto (as we see it in yellowed photos and in the paintings of Jan Minarík, Antonín Slavícek and other artists from the beginning of the twentieth century) was a result of its daredevil architecture, the dense interweaving and overlapping of misshapen, damp, run-down, tainted hovels, nests for the King of Mice and his subjects. It was a bizarre labyrinth of filthy, unpaved alleyways as narrow as mine shafts, where sunbeams rarely swept away the refuse of the shadow: ugly, fetid alleyways running through the belly of a dilapidated tenement only to end like bats on a blind wall; alleyways like crevices crisscrossed by patches of mould and foul smells; zigzag alleyways with streetlamps on the corner, cesspool-like puddles and arched wooden doors; alleyways, whose bends and curves lent them a certain drunken, wobbly, dreamlike quality.”

Angelo Maria Ripellino, Magic Prague, Trans. David Newton Marinelli, Ed. Michael Henry Heim (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994).

“In us all it still lives -the dark corners, the secret alleys, shuttered windows, squalid courtyards, rowdy pubs, and sinister inns. We walk through the broad streets of the newly built town. But our steps and our glances and uncertain. Inside we tremble just as before in the ancient streets of our misery. Our heart knows nothing of the slum clearance which has been achieved. The unhealthy old Jewish town within us is far more real than the new hygienic town around us. With our eyes open we walk through a dream: ourselves only a ghosts of a vanished age.”

Gustav Janouch, Conversations with Kafka (London: Quartet Books, 1985).

The Jewish Museum

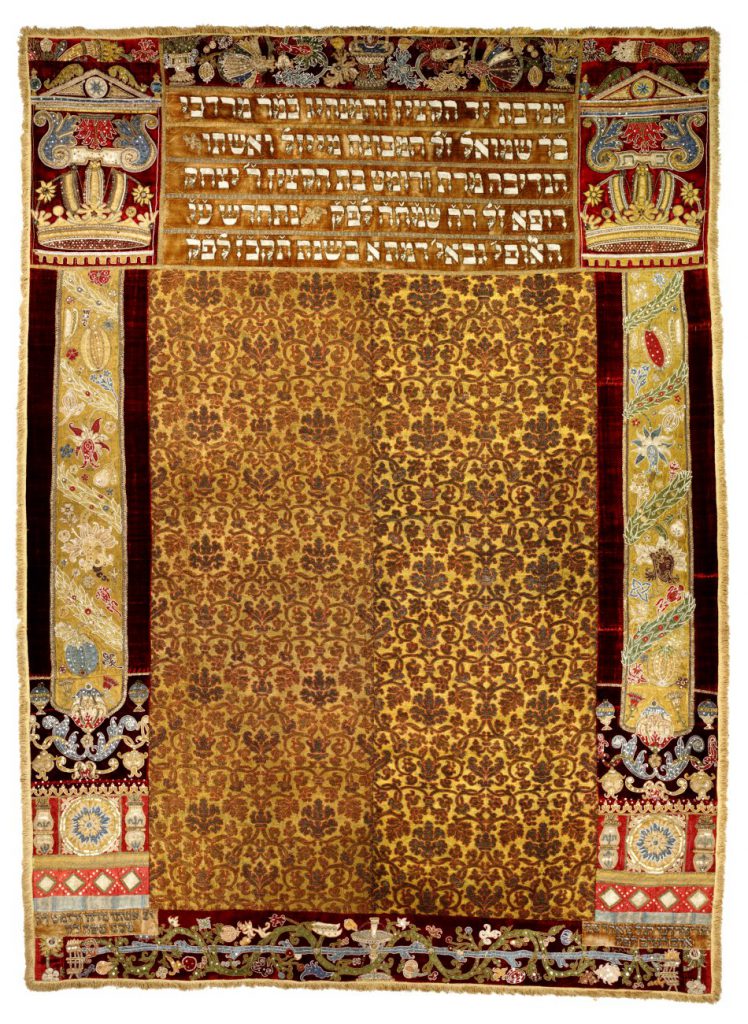

The Jewish Museum of Prague , created in 1906 as a symbol of Czech Jews’ assimilation, manages the synagogues and the old Jewish cemetery. It possesses some of the world’s richest collections of religious and domestic objects, manuscripts, paintings, and engraving gathered before the war, as well as numerous pieces that were pillaged by the Nazis in Bohemia and Moravia to be displayed in their “museum of the vanished race” that served their anti-Jewish propaganda machine in Prague. This stratagem ended up saving valuable objects and the several dozen intellectual employed to classify them. The idea for the museum had been nurtured by certain Jewish communities in the Czech lands that managed, with considerable difficulty, to convince the occupation authorities of the the worthiness of their plan.

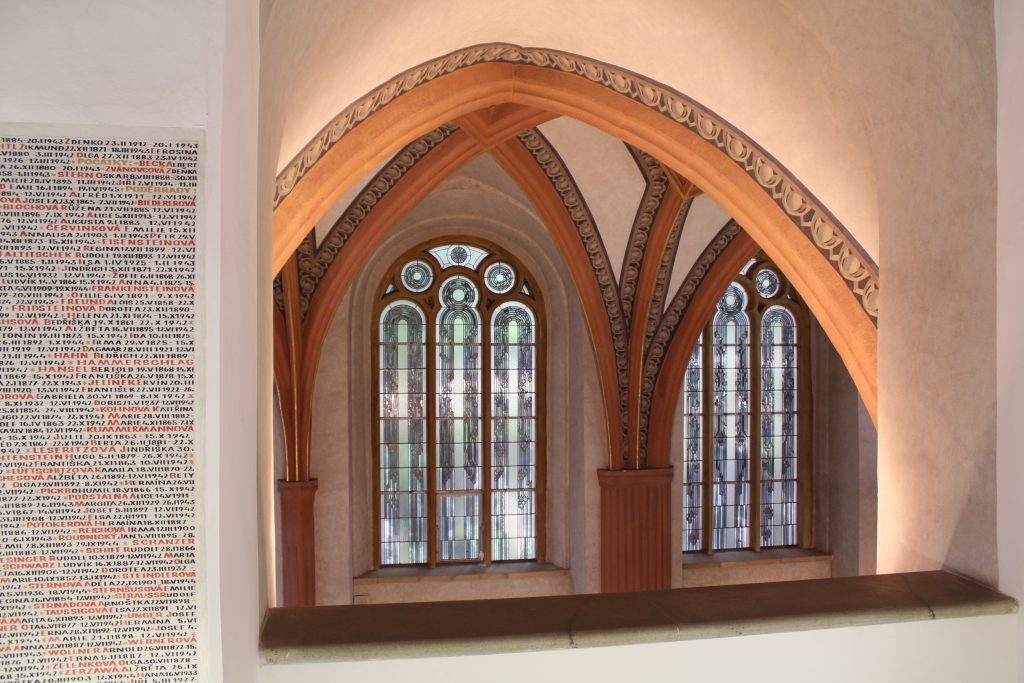

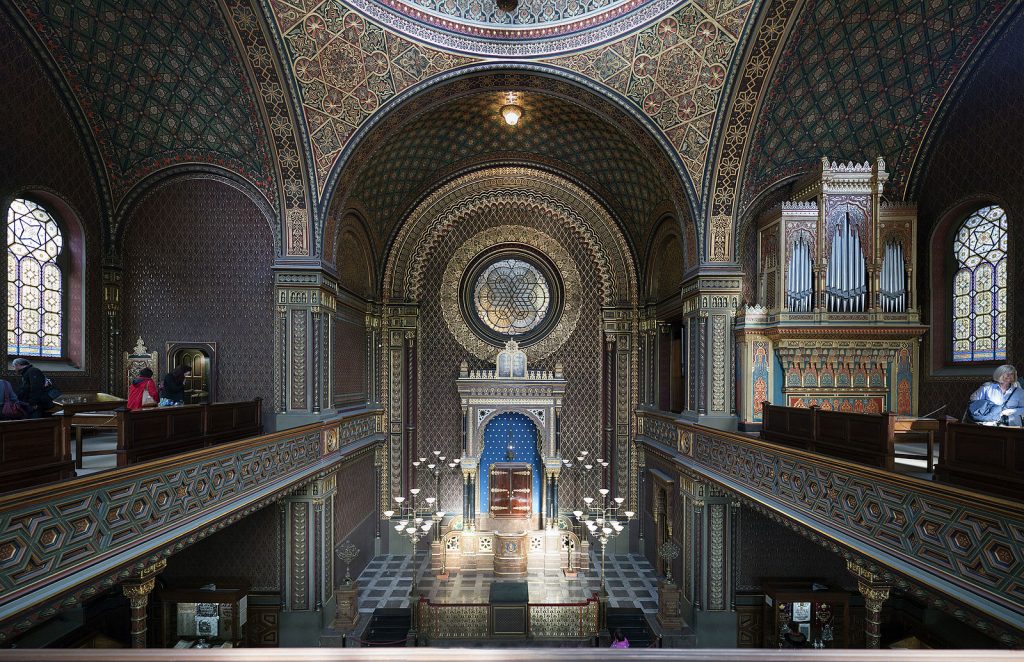

The majority of the employees of the Jewish Museum were finally deported in 1944, but the collections were saved. Under Communism it became the State Jewish Museum. The collections and so the heritage of the Jewish community of the Czech Republic were handed back in 1994. A selection of objects, the oldest ones, are displayed in the Meisel Synagogue and depict the history of the Jews in Bohemia-Moravia from their origins to the time of their emancipation. The rest of the exhibition, devoted to Jewish life from the eighteenth century until the end of the Second World War, occupies the rooms of the Spanish Synagogue, restored in 1998. The Pinkas Synagogue has a memorial bearing the names of the some 80000 Jews of Bohemia-Moravia who were victims of the Shoah.

The old Jewish quarter

A visit to the old Jewish quarter and its monument requires at least a full day, although the sites are all concentrated in a few streets between Pařížská and Kaprova avenues. Tickets valid for the entire tour can be bought at the entrance to the cemetery of the Jewish Museum. The synagogues and the cemetery are open every day except Saturday and Jewish holidays.

The jagged brickwork of the Staro-Nová Synagogue’s pediment looks as though it were pulled from an Expressionist film set. Now crowded on all sides by the surrounding buildings, this medieval synagogue set among the little streets of the ghetto has intrigued travelers and passerby for centuries with its narrow windows and strange facade. Today this synagogue is the oldest north of the Alps. Built in approximately 1280, it is even older than the Saint Guy cathedral of Prague. It was first called the “New”, and later on the “Old-New” Synagogue when other grand synagogues were erected in the quarter in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. None of the other synagogues, however, have so many legends attached to them. One legend claims the celebrated synagogue was built with stones of the Temple of Jerusalem brought by Jews from Palestine at the time of their exodus.

Another version of this tale recounts that the stone blocks were transported to Prague by angels. Other legends assert that when work began on the foundation, the synagogue suddenly rose from the ground after only a spadeful of earth had been dug. Abundant local romantic literature asserts that the Golem’s remains were located for many years in the synagogue’s rafters under its great, steep roof. Although it remains the most important and moving place of Jewish worship in Prague, the synagogue today is overrun with tourists.

Located on the Červená ulička (Red Street), the street names recalls the numerous butcher chops that existed on the small square nearby before the destruction of the ghetto. The replastering and other restorations of the synagogue have erased the patina created by centuries of lamp-oil smoke. The mildew stains on the walls that some had seen as traces of blood from the thousands of victimes of the pogrom of 1389 have likewise vanished. The synagogue’s interior plan is oblong, a borrowing from medieval monastic architecture. Two octagonal pillars support Gothic arches and separate the space into two naves. The interior layout is similar to that of the synagogue of Worms (1175) in southern Germany, which was torched by the Nazis.

For many years the nave was reserved for men; women followed the services from the hallway and through small windows. Standing between two columns, the fifteenth-century bimah is surrounded by a large Gothic grille and the wooden seats of the faithful. The first seat to the right of the pulpit, bearing the number 1 and crowned by a Star of David, once belonged to Rabbi Loew. The aron of the eastern wall features tow Renaissance columns. Finely carved stone floral motifs decorate the tabernacle. The prayer hall is illuminated by large wrought iron lamps. Carved grapes and vines adorn the magnificent tympanum of the great door to the prayer hall. These motifs are similar to those found in the famous Cistercian abbeys of southern Bohemia. Some historians believe that the same artisans worked on the structures of both faiths. The building’s heavy masonry has protected it from the many fires that have ravaged the ghetto over the centuries.

The Jewish city hall stands on Maislova Street, one of the ghetto’s principal arteries and at one time named the Zlatá ulička (Street of Gold). The building was constructed cira 1560 with funds given by Mordechai Maisel, the financier and philanthropist who was the quarter’s first mayor. Devastated by a fire 1754, the edifice was rebuilt according to the rococo-style plans of architect Josef Schlesinger. The city hall is crowned by a small tower with two clocks, one with Roman numerals and the other, beneath it, with Hebrew numbers and hands that revolve counterclockwise. This building is now the administrative center for the rabbinate and the institutions of the Jewish community. Decorated with stuccowork and Stars of David, the large “Hall of Advisers”, has been the home of a kosher restaurant, Shalom, since 1954. The restaurant is managed by the community and serves up generous portions.

Across Cervená Street, one of the few remaining little streets of the ghetto, and opposite the Stare-Nová Synagogue is the Vysoká (High) Synagogue . It belong to the same ensemble of buildings as the Jewish city hall and was built during the same period, in 1568, by the same architect, Pankratius Roder, from South Tirol. Damaged by several fires, notably that of 1689, it was remodeled at the end of the seventeenth century. The large prayer hall on the second floor retains its original appearance, with graceful arches of a mixture of late-Gothic and Renaissance styles and three beautiful windows on the northern wall and two on the eastern wall. The magnificent Baroque aron is located between the two windows of the eastern wall and dates from 1691. The synagogue was active until World War II, and again between 1946 and 1950. It has since become an exhibition space for a collection of sacerdotal vestments belonging to the Jewish Museum.

The Maisel Synagogue was erected at the edge of the ghetto by Mordecai Maisel, who bought a piece of land there is 1590 for the construction of a private synagogue. An inscription, almost completely effaced, celebrates the many charitable deeds of the philanthropist. Constructed in 1591-92 after a design by Yehuda Goldschmied de Herz and Josef Wahl, Maisl’s synagogue was the most elegant and richly decorated synagogue in the ghetto. It was destroyed by a fire in 1689, and rebuilt on a more modest scale. Again in 1754 the synagogue was devastated by fire. It was reconstructed in 1864, and made over yet again, this time from 1893 to 1905 in a neo-Gothic style, when the entire zone was cleaned up. The synagogue was restored in 1994, and it has served as one of the main exhibition spaces of the Jewish Museum since the early 1960s. On display you can find the permanent exhibition “History of the Jews in the Bohemian Lands in the 10th-18th centuries”.

The Klausen Synagogue was built in 1694 right next to the entrance of the Jewish cemetery and on the former site of the Klausers. The Klausers were three small buildings, one of which was a synagogue erected in 1564, and another of which was Rabbi Loew’s school. All three were destroyed in a major fire of 1689. The current synagogue takes its name from the Klausers, whose place it occupies. It was the second most important house of worship in the Jewish community. The building has been renovated several times, notably in 1883 by the architect Bedrich Münzberger, who enlarged the original structure and added an original women’s gallery from 1694. The majestic prayer hall, which features an impressive aron dating from 1696, currently serves as a repository of a permanent exhibition dedicated to “The Jewish Customs ans Traditions”. On the western wall, there is a magnificent aron of carved wood originally from the synagogue of Podboransky Rohozec.

The Pinkas Synagogue was built on the edge of the old cemetery in the fifteenth century for the Horowitz family and later enlarged in the middle of the sixteenth century. Erected in 1530, it was enlarged in a late-Renaissance style in 1625. The current building preserves the original plan, but the large Gothic nave with its rich polychromatic decorations have totally disappeared in the numerous renovations, especially those from the beginning of the seventeenth century designed by the architect Yehuda Goldschmied de Herz. The synagogue was altered again more than a century later, in 1862. The aron is Renaissance-Baroque in style. The stone bimah is enclosed by a lovely metalwork grille dating from the eighteenth century. Off to the side you can see the main remnants of a mikvah. In 1960 the walls of the synagogue were inscribed with the names and birth and death dates of the 77297 Jews from Prague and the surrounding Czech lands killed by the Nazis. The synagogue was closed for about about thirty years and was restored only in the late 1990s.

The Moorish-style Spanish Synagogue was built in 1868 and occupies the place where the oldest synagogue of Prague once stood. The Old School, as it was called, served the Byzantine community of Jews in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries. They had their own small ghetto separated from the Jewish quarter and near the Church of the Holy Spirit and a convent. The synagogue was destroyed by pogroms, including that of 1389, and several fires and rebuilt, each time to its original plan of a long hall covered by a steep roof. It became the first Reform synagogue in the city at the beginning of the nineteenth century, and an organ was installed. In 1868, it was decided to raze the older and set in its place a larger place of worship symbolic of the new role the most modern fringe of the Jewish community began to have in Czech society. Architect Johann Bělský, who also built many new houses in the Jewish part of town, chose the Moorish style so fashionable among Jewish communities (especially those of Germany) at the time. Erected according to architect Bedrich Münzberger’s plans on a square plan with a large dome, the interior of this synagogue is richly decorated with stuccowork inspired by the Alhambra of Granada. The synagogue has been restored and serves today as an exhibition hall for the Jewish Museum.

Around the time of the great urban renewal projects of the former ghetto at the beginning of the tewentieth century, three small synagogues were destroyed: the New Synagogue (end of the sixteenth century); the Tzigane Synagogue (seventeenth century, modified in the eighteenth), where the young Franz Kafka had his Bar Mitzvah at the age of thirteen; and the Synagogue of the Great Court (1626). The Synagogue of the Jubilee replaced these three and was constructed outside the old Jewish quarter in the Nove Mesto (New City). Erected in 1905-06, it celebrated the integration of Jews into Prague society at the beginning of the century. Constructed according to plans by the architect Alois Richter, its melds the Moorish style with Art Nouveau elements, especially in its interior design.

Other small synagogues were constructed during the same period in a variety of districts in Prague. Most of them, including Kralovske Vinorady, were destroyed during the air raids of World War II. The others were deconsecrated and transformed into warehouses or stores. Nevertheless, one can still admire the very interesting oriental style functionist building built in 1930 for the neighborhood Jewish community on Strupewnického Street in Smíchov (in the southwest part of Prague). In Karlín (in the eastern part of Prague) a tiny neo-Renaissance synagogue was constructed in 1860 and then transformed into a Hussite church. It can still be found on a small street in the countryside cakked Vitkova Street.

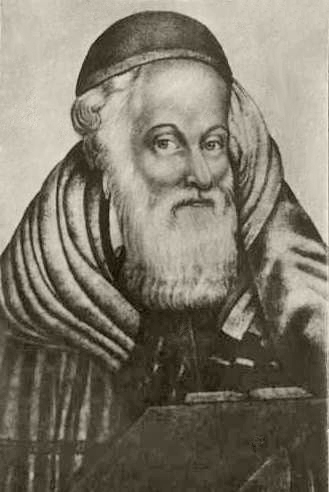

Rabbi Loew

Astronomer and mathematician, Rabbi Loew was born around 1525 near Poznan (in present-day Poland). The most respected Jewish thinker of his time, Loew was a renowned interpreter of the Talmud and the Law. Though above all a scientist, in the popular imagination of the nineteenth century he became a great Kabbalist, even a Jewish Faust, who had created a Golem, an artificial man of clay who escaped from his creator.

He was invited to meet Rudolf II on 16 February 1592, and according to legend, made shadows of the great figures of Genesis and the Patriarchs appear on the walls of the room. It was also reported that he succeeded in avoiding death for several years by tearing from Death’s hands the list containing the names of those slated to die. Death did manage to catch up to him, hidden in a rose his granddaughter gave him to smell. He died in 1609.

Although the cemetery’s wellmarked hallways have been cordoned off to prevent to tens of thousands of tourists who file through it each year from walking on the graves, the old Jewish cemetery in Prague remains the most famous and interesting in Europe. It is best to visit it either very early or very late in the day, or outside the tourist season altogether, in order to capture the poignant nostalgia of the place. Some 12,000 gravestones are piled one upon another -sometimes three or four deep or more. The grounds are a hodgepodge of crooked stones, like swaying drunkards, buried almost to their tops, covered in ivy, and swallowed up by the damp, black earth. A few trees, mostly alders and elms, manage to grow in this mass of stones, their inclining trunks recalling the gravestones worn by the weather and caresses of the faithful.

You can still make out the inscriptions in remembrance of the dead, and often the bas-reliefs symbolizing a family name, occupation, or the virtues of the deceased. Hands in a gesture of blessing indicate the tomb of a Kohen (or Cohen, Kohn, Kahn, or Kagan), descendants of Aaron and the great priest of the Temple, the Kohanim. The pitcher or basin adorning many gravestones marks the final resting places of the Leviyim, or the Levites (descendants of Levi), the second group in line after the Kohanim to read from the Torah during celebrations at the synagogue. Other motifs, such as palm leaves, recall the verses from the Psalms, “The good man will flourish like a palm tree” (Psalm 92:13). A bunch of grapes symbolizes abundance and the kingdom of Israel.

Despite the prohibition against representing the human figure, there are a few feminine silhouettes carved onto tombs dating from the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, symbolizing, according to the tradition, the desire of God to enter the hearts of men. Other, more prosaic images represent an occupation, such as a boat for merchants, tweezers for doctors, or scissors for tailors. There are also many sculptures of animals, first and foremost the lion, representing the royal kingdom of Judah and the twelve tribes of Israel or recalling the name of the deceased (Löwe, German for “lion”, or Leyb in Yiddish). The bear also figures in this stone bestiary, suggesting the search for honey that symbolizes the Jew immersed in the sweetness of the Torah. Also depicted are the doe and the gazelle (“because God runs to the synagogue to hear the prayers of Israel”), as well as birds.

The oldest tomb is that of Rabbi Avigdor Kara, which dates to 1439. An older cemetery, desecrated at the time of the pogrom of 1389, was found near the present-day Vladislavova Street in the Nove Mesto. The last tombs were erected in 1787, the year the cemetery was closed at the command of Emperor Joseph II. Small stones are placed on the most celebrated tombs, such as the one decorated with lions of the wise and holy rabbi Yehuda Loew ben Betsalel (1512-1609), called Maharal and reputed to have performed miracles even after his death. Pilgrims slide slips of paper with their requests and prayers in the crevices of the red stone. Another venerated tomb is that of Mordecai Meisel (1528-1601), the philanthropic financier who was mayor and benefactor of Prague’s Jews. The epitaph on his tomb recalls that “his generosity was without limits and his charity was given with all his heart and soul”.

The Zizkov cemeteries

The earliest graves of the Old Zizkov cemetery date to 1680, but the cemetery really began to grow after 1787 with the closing of the one in the old ghetto. In the restored section one can see lovely Baroque and classical sepulchers. The last burials date from 1890. Part of the cemetery has been transformed into a park. There is also a television transmission tower on the grounds.

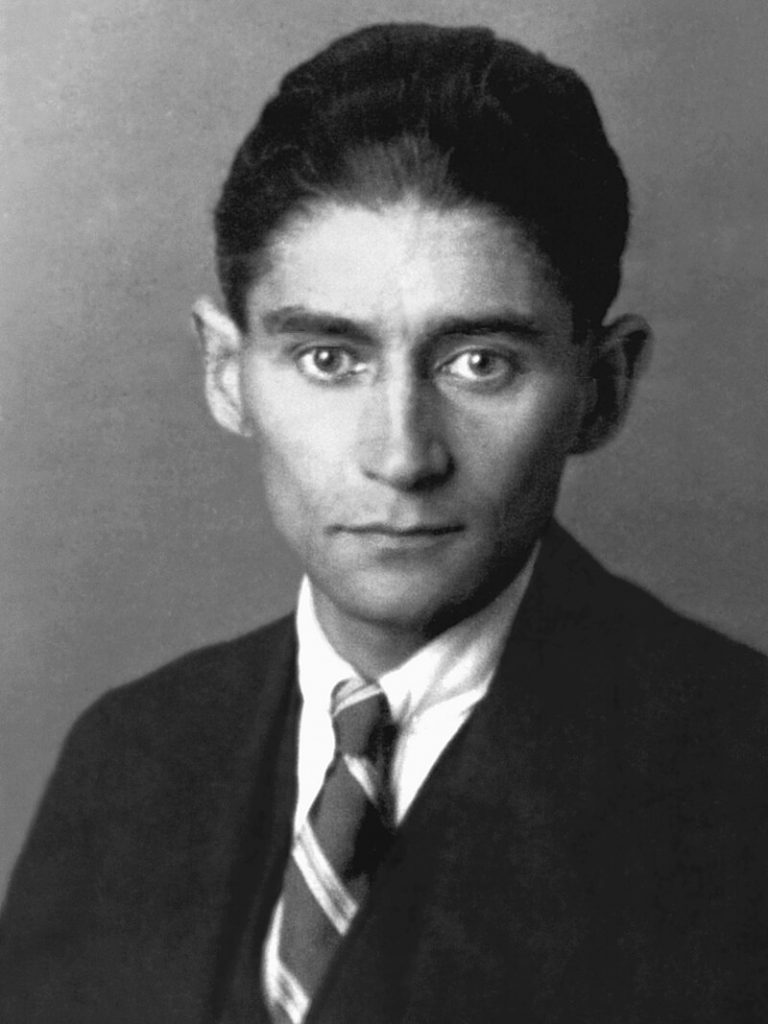

The new cemetery , established in 1890, is Prague’s only Jewish cemetery still in use. The large hall, which also houses the administrative offices, was constructed in a neo-Renaissance style at the end of the nineteenth century. The cemetery includes magnificent tombs in the Art Nouveau, neo-Gothic, and neo-Renaissance styles. Franz Kafka is enterred here beside his parents. The tomb is crowned by a sober gray stone stele where visitors often leave small stones in homage. Opposite is the grave of the writer Max Brod, Kafka’s friend and confidant, who, after Kafka’s death, refused to burn Kafka’s writings despite the demand in his will.

The Franz Kafka houses

A visit to the nostalgic sites of Jewish Prague would not be complete without a trip to the places where the most famous Jewish author lived. All his life, despite his parents’ many changes of residence and his own, Franz Kafka stayed within a narrow perimeter of the old city center around the large square, some three hundred feet from the former Jewish quarter.

Kafka’s birthplace (at 5 Radnice Street) is situated on the northeast side of the large square. He was born here 3 July 1883. Of the original building destroyed in a fire in 1896, only the main entrance remains. A bust commemorating the writer was placed there in 1965.

Two years after their son came into the world, Kafka’s parents moved. After some wandering around the quarter, they settled in the U Minuti House on the old city square, near the great clock. The facade of this seventeenth-century building is decorated with biblical scenes and classical legends from antiquity. Kafka lived here from age six to thirteen; his three sisters Elli, Valli, and Ottla, who died while being deported, were born here.

In 1896, the Kafka family moved into a lovely old home, “In the Name of the Three Magi”, at 3 Celetná Street. Kafka, whose bedroom faced the street, remained here until the time of his law studies. His father’s first store, Hermann, was a little further away at number 8 of the square on the north side, but it has not been preserved. A few years later, Kafka’s father moved his business to Celetná Street, and then, in 1912, to the ground level of the imposing Kinsky Palace on the square. The German lyceum that Kafka attended was located in a wing of this building.

In 1907, about the time Kafka had begun working at Assicurazioni Generali, the family settled at 36 Niklasstrasse (now Parizká Street) in a elegant building constructed on the ruins of the former ghetto. The house, zum Schiff (like a boat), was very close to the Vltava. Here he wrote three of his masterpieces, The Judgement, Amerika, and The Metamorphosis. The building was destroyed in 1945.

In 1913, the Kafka family returned to the old city square to live in the Oppelt House (Starometseke Námesti): Kafka’s bedroom faced Parizká Street.

In 1914, Kafka left for nearby 10 Bilkova, lent him by his sister Valli and where he began to write The Trial.

Beginning in May 1915, Kafka lived alone for the first time in the “House of the Golden Pike” (now 16 Dlouhá Street). “Without a broad view, without the possibility of seeing a big swath of the sky, or at least a tower in the distance to compensate me for the lack of open, empty countryside -without all that, I am an unhappy man, a man oppressed”, he wrote to Felice Bauer at the time.

He next lived for a few months on the other side of the river in a little house at 22 Zlata Street (Little Street of the Alchemists), near Prague Castle. In May 1917, he also rented an apartment in the magnificent Schönborn Palace (15 Trziste), today the location of the American embassy.

Jewish sites in Christian Prague

Some of Prague’s extraordinary architectural heritage is directly tied to the Jewish past.

On the Charles Bridge, the third statue on the right coming from the old city represents a Christ bearing a large golden inscription in Hebrew (“The Holy One, the Lord”) paid for as a fine in 1696 by a Jew accused of having blasphemed the name of Jesus.

In the Church of Saint Mary of the Tyn in the old city square, there is a plaque commemorating a “hero” of the Counter-Reformation. “Solemnly buried here is the fellow believer of the Catechism, Simon Abeles, killed in the name of hatred of the Christian faith by his own father, a Jew”, states the text, recalling the young Jewish boy, aged twelve, who, tempted to convert, was killed by his father and his father’s friend 21 February 1694. Arrested in the old city, Lazar Abeles, the father of the victim, hanged himself by his prayer shawl in his cell in the city hall. The corpse was dragged outside the city walls, drawn and quartered, mutilated, and his heart was placed on the mouth of his slain son. His accomplice, one Löbl Kurthandl, was tortured on the wheel until he renounced his faith, after which he was put to death. The remains of the child were found intact in the Jewish cemetery -a sign of a miracle- and were laid out for a month in the church of Tyn. During this time, the village and the clergy filed past past the body to pay their respects. In the years between the two world wars, several historians, including Egon Erwin Kisch, examined records of the trial and forever put to rest the legend forged by the Jesuits in the seventeenth century. The circumstances surrounding the death of the child remain unclear, but the charges were entirely fabricated in order to force the guilty to convert.

Approximately thirty miles northeast of Presov, the small city of Stropkov had one of the largest Jewish communities in the region and was an important center of Judaism.

Many of its Jews arrived from Poland in the seventeenth century, victims of the pogroms who were in search of the relative security in lands belonging to the Hapsburg Empire. Although allowed to work in the city, they did not have the right to live there or bury members of the community within the city limits. For decades, Jews were thus compelled to bury their dead in the cemetery of the neighboring village of Tisinec.

Stropkov’s Jewish community experienced significant growth in the eighteenth century. Stimulated by the teachings of famous rabbis such as Chaim Yosef Gottlieb and Yekutiel Yehuda Teitelbaum, Stropkov became one of the most prestigious centers for the study of the Torah in all of greater Hungary and Galicia. Today there is not a single Jew left in the city. Most of the houses and shops of the Jewish quarter were razed after the war. The memory of this community lingers in but a few scattered tombstones in the cemetery .

Bardejov possessed a large Jewish quarter where some 5,000 Jews lived before World War II. This small medieval city of 35,000 inhabitants lies thirty-seven miles north of Presov, near the Polish border. Most of Bardejov’s Jewish community was wiped out during the war.

Despite the devastations of the war and postwar reconstruction, a few houses and an interesting eighteenth-century Polish-style synagogue remain. It was restored in 2011. Visit the website Bardejov Jewish Preservation for more information about Bardejov.

The Jewish presence in Bardejov probably dates back to the 13th century. But it was not until the 18th century that the community developed. In particular, it became an important centre of Hasidism, with the rabbis of the Halberstam dynasty.

The large synagogue was built in 1830. The Jews worked mainly in the export of wine to Poland and in crafts, and played an active part in the economic development of Bardejov and its spa. More than 2,000 Jews lived in Bardejov in 1930 and a large number of them perished in the following decade during the Holocaust.

The town became a rehabilitation centre for survivors and a transit point for aliyah before Israel’s independence. Most Jews emigrated gradually. Ritual objects from Bardejov are preserved in the Divré Ḥayim synagogue in Jerusalem, named after Rabbi Ḥayim Halberstam, the founder of the Bardejovian Sanz dynasty.

Jack Garfein, who was born in the Ukrainian town of Moukachevo but grew up in Bardejov, devoted a film to his return to Bardejov, recounting in particular how he had survived the Holocaust. He went on to become a theatre teacher, producer and one of the most important directors of the post-war period, thanks to the cult films The Strange One (1957) and Something Wild (1961).

There’s also a Jewish cemetery in town.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Not far from Kosice, Presov was also an important center of Jewish life. More than 6,000 Jews from the city and surrounding villages were killed during the war. Today fewer than 100 Jews live here in Presov.

The area from near the old city center with its Renaissance homes and palace to beyond the city walls once marked the extent of the Jewish quarter.

Close to the Jewish community center near the city walls stands a beautiful synagogue from the last century. A monument commemorating the victims of the Shoah stands in the center of the quarter. Remnants of two cemeteries, one Orthodox and the other Reform, can be found near the Catholic cemetery.

The capital of eastern Slovakia, Kosice is a large industrial city of 250000 inhabitants. Its sizable Jewish community was almost totally annihilated during the Second World War. The city os now home to 800 Jews.

The spacious nineteenth-century synagogue is in a building adjacent to the community headquarters. The building also includes a mikvah, a kosher butcher shop, and a prayer hall. This particular arrangement, unique in Slovakia, suggests a picture of Jewish life in this city before the Shoah. The city also has a new synagogue and a Jewish cemetery .

Trencin is a city of roughly 60,000 inhabitants, and you will find on Vajanskeho Street a beautiful synagogue dating from the beginning of the twentieth century. Although now an exhibition space, its decorations remain, and a plaque recalls that the building was once the location of worship for the 1,300 Jews in the city, most of whom were exterminated during World War II.

The Jewish presence in Trencin probably dates back to the 14th century.

Just over 200 Jews attempted to revive the community after the war. In 1978, a memorial was inaugurated in the cemetery in memory of the Jewish anti-fascist fighters.

Bratislava, capital of Slovakia and a large city of more than 500,000 inhabitants, is located on the banks of the Danube River, not far from the Hungarian and Austrian borders. Although Jews may have lived here since the Roman period, the first mention of a community dates back to the second half of the thirteenth century.

The Jews of Bratislava have been expelled from the city several times in its history, notably in 1360 and in 1526. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, a census counted 120 Jewish families in the city. During this period, the community began to grow, notably with the influx of Jews coming from Moravia. With the arrival of Rabbi Moses Schreiber, known as the “Hatam Sofer” (1762-1839), the city even became a center of European Judaism. At the very end of the nineteenth century, many Jews arrived in the capital city from the villages of western Slovakia. More than 15,000 Jews lived in the city at the dawn of the Second World War. Many buildings in “Jewish Bratislava” were destroyed during the war and the great urban renewal of the Socialist period.

The Grand Orthodox Synagogue, constructed in an oriental style in 1863 on Zamoska Street, was largely destroyed in 1945. Its remains were razed in 1980.

The large Moorish-style Reform synagogue, so much a part of the landscape near present-day Paulinyho Street, was knocked down in 1970 to make way for a parking lot and highway ramp. Zidovska Street (“Street of the Jews”) wounds its way between the walls of the city and the castle. Several fires (in 1913, for example) destroyed a number of seventeenth and eighteenth-century houses, the last of which were cleared away after 1945. The Jewish Museum is housed in one of the few buildings that survived this period.

Deprived for many years of a spiritual leader, Bratislava’s small Jewish community (at most 1000 members) has, since the fall of Communism, been under the direction of Rabbi Baruch Myers, educated in Brooklyn within the ultra-Orthodox Hasidic Lubavitch (chabad) movement. Information about Slovakian Judaism is available at the Institute of Jewish Studies.

The Jewish Museum constitutes a section of the National Museum of Slovakia. Since 1991, it has been housed in an urban villa dating from the late Renaissance that has been remodeled several times after fires ravaged the street in the seventeenth and nineteenth centuries. The collection of the Jewish Museum in Presov are now contained here. Objects of worship and antique books, some from the Hatam Sofer library, are on display. The galleries of the museum illustrate the life of Slovakian Jews during the last five centuries and celebrate important figures of the community. The permanent exhibition ends with a commemoration of the victims of the Shoah.

Only one synagogue remains in Bratislava. An austere but elegant building in an oriental style, it was constructed for the city’s Orthodox Jews in 1923 following the plans of architect Arthur Szalatnai-Slatinski. It is open for Shabbat services as well as Monday and Thursday mornings.

Perhaps the most moving and symbolic monument in Bratislava is the mausoleum of the Hatam Sofer in the so-called Vajanskeho Nabrezy. The tomb stands in a large underground crypt beneath a highway. It remains one of the important pilgrimage sites for Orthodox Jews in Central Europe. Rabbi Moshe Schreiber, called Hatam Sofer for his great wisdom and penetrating interpretations of the Law, was one of the primary leaders of early modern Orthodox Judaism. The twenty-three tombs and forty-one gravestones are the last vestiges of a Jewish cemetery that was in use until the middle of the nineteenth century. It was razed during the war.

Not far from the mausoleum, some 600 feet up the hill (the entrance is on Zizkova Street), is an Orthodox cemetery established in 1846 and still in use today. Many of the 7,000 tombstones here are from older cemeteries elsewhere.

Half a day will suffice to see the synagogue in Szeged, one of the most interesting ones in Hungary (1903).

With its Baroque dome, Roman columns, and Byzantine-inspired bellows, the monumental building is a hymn to eclecticism. At the entrance, two plaques honor rabbis Lipot, a reform pioneer who was the first to deliver his sermons in Hungarian, and Immanuel Loew, son of the former, whose passion for botany inspired the floral motifs of the decor. On both sides of the nave, beautiful stained-glass windows count out the Jewish holidays.

Everything exudes opulence: the aron and bimah are made out of the marble from Jerusalem, while the menorot are made from ormulu set in semi-precious stones. Jews prospered here thanks to commerce and the wood and paprika industries. The dome’s superb stained-glass windows are by the famous Jugendstil artist Miksa Róth. Concerts are sometimes held here, with the money going to helping maintain the synagogue.

There’s also a Jewish cemetery in Szeged.

Kecskemét is worth a stop for its two synagogues. The largest is in (nineteenth-century) Romantic style. Today it houses the Technology Center , where expositions and conferences are regularly held on technical subjects.

The second contains a small Museum of Photography .

There’s also a Jewish cemetery in the city.

The region is famous for its rebbes, heads of Hasidic communities whose followers revered their thaumaturgical and magical powers.

The city of Sátorajújhely, where 4,000 Jews lived in 1939, houses the mausoleum of Moses Teitelbaum. Born in Poland in 1759, he founded a dynasty of rebbes in Hungary, Galicia, and Romania. Every day, legend has it, Teitelbaum dressed in rags and climbed Mount Sator to see if the Messiah had come.

The archives in the city hall contain documents in Hebrew available for examination.

There’s a Jewish cemetery in the city. The Jewish cemetery was restored in 2020, thanks to the efforts of Bence Illyes, a photographer and researcher in Jewish studies, who brought together many Christian and Jewish volunteers in this effort.

Built in 1795, the synagogue looms over the old Jewish quarter with its elegant white facade. With the Protestant church on the other side of the small valley, it symbolizes the religious balance of a large wine-making village, a quarter of whose inhabitants were Jews at the end of the nineteenth century. It represents a very beautiful and rare example of a Baroque synagogue in Hungary.

The interior is splendid, and the harmony of its proportions is striking. The graceful, wrought in iron bimah is located in the very center beneath a supporting architrave on four columns, in accordance with Orthodox tradition. The refined aron is sculpted from stone and decorated with a beautiful medallion (lions and griffons surround the Ark of the Law and cherubs hold rimmonim). Engraved on the fragments of stone surrounding the steps can be seen the prayers of Yom Kippur and the new moon, as well as a text written in Aramaic. The multicolored frescoes were added later.

Make sure to visit the old cemetery . It is even older than the synagogue, with some graves dating from 1650.

In the seventeenth century, the Jews of Galicia and Silesia (modern-day Poland and Ukraine) were drawn to this region by trade in tokaj, a syrupy, amber-tinted wine very popular at the courts of Louis XIV and Peter of Russia.

Jews gradually settled here, producing wine for Jews and non-Jews alike, and a crowd of other small trades followed subsequently. In this very Orthodox region, Hasidism took root and Jews here resisted assimilation until the Second World War.

The Memoirs of Ber, Jewish merchant of Bolechów (today in Ukraine)

“Once Poniatowski (the local count) said to Saul: “I should like to send someone to Hungary to buy me a considerable quantity of good wine. If you know of a fellow-Jew, a trustworthy person who understands the business, I will send him. […] He accordingly decided to send my father for the wine and handed him 2000 ducats, that is 36000 gulden. He also sent with my father the tutor of his sons, in the capacity of a clerk, in order to register the purchase of the wines and the daily expenses, so that a proper account might be kept. The clerk was named Kostiushko. My father did as he requested by Poniatowski. He bought 200 casks of Tokay wine of the variety called máslás. When they both returned from Hungary and brought the wines to Stryi, Poniatowski was very pleased with the purchase; he gave my father 100 ducats for his trouble, and for keeping the accounts properly the clerk Kostiushko was promoted to be steward of our native town Bolechów…”

Ruth Ellen Gruber, Upon the Doorposts of Thy House (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1994).

The synagogue on Achim Street, built in 1890, accommodated 1800 of the faithful. Damaged by a fire in 1999, it cannot be visited, but it is possible to explore the old Jewish quarter surrounding it: the L-shaped yeshiva, mikvah, beth hamidrash (a study room, in the small white building), and bakery (with orange walls, on the street side). The poor lived by the river’s edge, those of the middle class toward the city center.

Polisi!

In the nineteenth century, Jews acquired vineyards and got rich from industry. At the same time, the poor continued immigrating to Hungary. In 1927, Albert Londres sketched the appalling misery of these Hasidim who came from the north, scornfully labeled polisi (Poles) by the wealthy Jews of Budapest:

“The babies were dressed in shirts, their bare feet pressed against the ice… The mothers held their shawls open, revealing milkless breasts and fleshless ribs. Twice the husband of one such tried to make it down to the cities to find some bread, and twice he collapsed in the street, exhausted. In two years, misery here increased tenfold. Before the most recent peace treaties, these Jews worked three months every summer on the infamous Hungarian plain. The border separated the plain from the mountain. Hungary has refused passports to its former subjects, who have now become Czechoslovakian subjects. Three months of work was all these Jews needed to live for the rest of the year. All year long now, they will have only the meager fruit of the trees of the Carpathian Mountains!’

Albert Londres, The Wandering Jew Has Arrived. Paris: Le Serpent à Plumes, 2000). See also, The Jew Has Come Home, Trans. William Staples (New York: R. R. Smith, 1931).

Located on a wooded island in the middle of the Bodrog River, the very moving ancient cemetery is worth a visit. The scores of mossy graves here are disturbed only by ducks. The community acquired the land when Jews were forbidden to live in the city by Archduchess Maria Theresa in the eighteenth century.

Within this Baroque city, where splendid thirteenth-century houses have been transformed into museums, restoration projects have brought two medieval synagogues back to life.

Built in the early thirteenth century, the synagogue on Uj street is the oldest one in Hungary. So closely does it resemble the one in Miltenberg (Bavaria) that historian Ferenc David suspects Sopron’s Jews originated there. Emigrating from Germany and southern Bavaria, they possibly took up residence in Sopron, a royal and independent city at the time where monarch Laszlo IV had granted privileges to bankers and merchants -the only professions Jews were allowed to practice.

Like many medieval synagogues, the building, which in times past served a scale-down but flourishing community, is set back from the street. The raised entrance opens onto a Gothic-style room. The magnificent stone-sculpted aron is surrounded by a frieze adorned with grapes and fig leaves in homage to wine, a symbol of life and celebration of the kiddush during the Shabbat. To its right, a boarded-up window was enlarged to allow barrels to pass through. After the Ottoman occupation, the Jews were expelled in 1526 and their businesses transformed into residential housing. The adjoining room, added later (in the fifteenth century), was reserved for women, who could only observe ceremonies through narrow openings, a kind of horizontal loophole. In the courtyard, a Mikvah dates from 1420.

Located at number 11 on the same street -formerly “Jewish Street”, where Jewish and Christian merchants lived side by side- a small synagogue was built in 1350 modeled after the one that preceded it. More precisely, it was a private prayer room belonging to the rich banker Israel and his family.

There’s a new synagogue in Sopron, as well as a Jewish cemetery .

The immense gray dome of Györ’s synagogue stands out against the industrial landscape. Completed in 1870, the structure reflects the prosperity of the city’s Jewish middle class -lawyers, bankers, and manufacturers of German or Moravian origin. The massive bronze pillars supporting the octagonal building contrast with the subtlety of the eastern-inspired decor of the galleries, beams, and frescoes. The adjacent building, a former Jewish school, houses the Széchényi art high school.

In a sorry state, the building is slowly being restored by the dynamic association that also organizes concerts and festivals here: in the last week of April through May 2, Györ welcomes a cultural festival called “Mediawave“, presenting films and shows from around the world. Concerts (folk and ethnic music or jazz) are held in the synagogue.

The peaceful Neolog cemetery is located on the bank of the Rapca River beside the Catholic cemetery. It is remarkably well kept -unusual for Hungary- by the caretaker couple who live at the site, Mr. and Mrs. Sandor Seles.

Along the road leading from Györ to Sopron, not far from the city’s limits, a statue on the right stands in honor of the great Jewish poet Miklós Radnóti. He died from exhaustion -or perhaps was gunned down- after a forced march from the Balkans to Austria in November 1944.

Razglednice

“I fell beside him; his body turned over,

already taut as a string about to snap.

Shot in the back of the neck.

I whispered to myself: just lie quietly.

Patience now flowers into death.

Der springt noch auf, a voice said above me.

On my ear, blood dried, mixed with filfth.”

Miklós Radnóti’s Last Poem, 31 October 1944, in Miklós Radnóti, The Complete Poetry, Ed. and Trans. Emery George (Ann Arbor: Ardis, 1980).

Visiting Budapest requires at least three days. The capital was born from the unification of three cities: Buda and Óbuda on the western shore of the Danube, and Pest on the eastern shores. Although wars and urbanization have left few traces of the Jewish presence in Buda, Pest contains an old Jewish quarter that still houses a portion of the community.

Buda

“There are a few Jews here and they speak French well; many were expelled from the kingdom of France”, Bertandon de la Brocquière noted in his 1433 Chronique de voyage à Boude (Chronicle of My Trip to Buda). The earliest arrival of Jews from Vienna certainly began as far back as the eleventh century. King Béla’s 1251 charter granted Jews the right to settle here, which offered them protection until the Ottoman era. Of the medieval period, only vestiges of a synagogue remain in the Baroque castle district. In the late fourteenth century, Jews built a large synagogue at 23 Táncsics Street, which was formerly called “Jewish Street”. The ruins here have yet to be restored.

Somewhat smaller, the synagogue at number 26 was a house of prayer, a temple serving the capital’s Sephardic community. Propped up by two Gothic pillars, the prayer room shelters two beautiful frescoes. One depicts a bow turned toward the sky, the other a star of David. The caption reads: “Powerful men equipped with bows were corrupt, while the weak were invested with power”.

The other Hebrew inscriptions, featuring Turkish stylizations, relay the fears of Sephardic Jews under Christian attack. Such fears were not unfounded: on one of the synagogue’s wall, the reproduction of a painting illustrates how the Jews of Buda were massacred in 1686 after the Turk’s defeat by the Austrians; they had been accused of collaborating with the Ottomans. Under Turkish occupation, Sephardic and Ashkenazic Jews had lived in harmony in Buda.

The Jews of Buda

“In the Jewish quarter of Buda one could buy almost everything: Persian carpets, kilim, velvet, muslin, fine linen, atlas, felt, aba cloth, frieze cloth, Moroccan leather. Fruits, even the most exotic ones that grew in the remotest corner of the Sultan’s empire, were sold there, as well as cattle, hide, flour, salt, timber. Credit was also available, against promissory notes. Jewish merchants played an important role in the ransoming of Christians who had been taken captive. Servants, too, were sold on the market.

Trade in wine, however, was prohibited even to the Jews. In order not to tempt the virtues of the Moslem population, the Turkish authorities forbade the use of wine, even in Jewish ceremonies.”

Géza Komoroczy, Ed., Jewish Budapest: Monuments, Rites, History (Budapest: Central European University Press, 1999).

Pest

Jews settled north of Pest’s current center, Deák Square, around a market where they sold grain, cattle, wool, and hides. In 1800, they numbered more than 1000 and soon built a synagogue in the Orczy House (destroyed) on the site of Madach square. Besides the synagogue, a rabbinical school was founded here, along with other school, baths, housing, and shops. Letter-writers rubbed elbows with matchmakers. The famous Café Orczy opened in 1825, where cantors were regularly recruited. Enriched by trade and industry, the nascent Jewish middle class soon wanted a temple worthy of its rank. The synagogue on Dohány Stret was opened in 1859, only a few years before the Jewish community gained full emancipation.

Here begins a tour of Pest’s Jewish quarter, delimited roughly by three synagogues that form a sort of triangle and represent the three branches of modern-day Judaism.

The assimilation of Hungarian Jews

Starting in the latter half of the nineteenth century, many Jews “Magyarized” their names.

“The teacher turns two pages. Maybe he has reach the letter K. Altmann who at the beginning of this term had his family name changed to the Hungarian Katona, now bitterly regrets this rash act.

Frigyes Karinthy, Please Sir!, Trans. Istán Farkas (Budapest: Corvina Press, 1968).

The synagogue on Dohány Street was designed by Austrian architect Ludwig Förster. Inspired by Vienna’s Tempelgasse synagogue and the Solomon Temple, Förster created an imposing structure, adding two towers to echo the columns of the Temple of Jerusalem. The outer, light-red brick walls are decorated with eastern and Byzantine-inspired motifs and are of a Moorish style very popular at the time. Förster’s work features a striking mix of Gerco-Roman, Roman, and Byzantine elements, integrating modern techniques: thin pillars of tempered steel support the upper galleries and roof, while the lighting comes from above.

Certain features are reminiscent of Christian church architecture. Unlike Orthodox synagogues, the bimah here is not found in the center but in the extension of the richly decorated aron, and it is modeled like an altar. A huge arch (40 feet in diameter) separates the sanctuary from the nave. One detail that scandalized Orthodox believers of the era was the presence of an organ, despite the traditional ban of musical instruments during Shabbat. The “Jewish Cathedral”, as some of its detractors have called it, symbolized the triumph of Neolog Jews, partisans of assimilation and modernization of Judaism. It is today the largest synagogue in Europe (254 ft. x 88 ft.) and served as the model for the one on East Fiftieth Street in New York City. Restored in the early 1990s by the Hungarian state, the synagogue can accomodate as many as 3,000 people. It is packed during major celebrations (Yom Kippur, Rosh Hashanah), were women can freely mingle with men.

The small adjacent museum has on display beautiful ritual objects, sacred decorations, and photos taken during the Shoah. Between the synagogue and museum, the remains of a redbrick wall signal the border of the ghetto built in late November 1944 and liberated by the Soviets on 18 January 1945. Through the arcades of the courtyard, the mass graves of Jews who died in the ghetto can be seen. Here also stands the Temple of Heroes: built in 1929 as a memorial to soldiers fallen during the First World War, it serves today as an everyday house of worship.

Behind the synagogue, a Shoah memorial stands in the middle of an open courtyard. The work of sculptor Imre Varga (1990), this steel and granite weeping willow is in fact an inverse menorah. The black marble arch symbolizes the Ark of the Law, hollowed out by the annihilation of the Shoah. The park is dedicated to Swedish diplomat Raoul Wallenberg, who saved thousands of Jews during the war. Saving Angel, an ormulu sculpture on Dob Street, has been erected in honor of another righteous soul, Swiss consul carl Lutz.

The synagogue on Rumbach Street , a major work by Austrian architect Otto Wagner, was built in 1872 for the traditionalists who refused to take sides on the dispute between Neologs and Orthodox Jews. In Romantic-Moorish style, the building’s exterior is decorated with numerous Arab-inspired motifs and two turrets shaped like minarets. The synagogue was given back to the Jewish community by the Hungarian government in 2006, the authorities helping the much needed restoration. It reopened as a polyvalent Jewish cultural center in 2020.

The Orthodox synagogue is pure Art Nouveau, built in 1913 according to plans by the Löffler brothers. Severely damaged during the war, it has been almost entirely restored to its original state. The superb ceiling is decorated with eastern-inspired floral motifs, palms, and lotus flowers typical of late Jugendstil. The stained-glass windows, in a ring, diffuse an optimal light, while very stylized menorot decorate the galleries, banisters, and windows. The gilded marble aron is the work of Italian masters. In the courtyard, you will notice the huppah, a dais of forged iron under which Orthodox Ashkenazic Jews celebrate outdoor marriages. The courtyard also houses a small prayer room (only holidays are celebrated in the synagogue), a kosher dining hall, a yeshiva, and a butcher shop.

The only functioning mikvah is Hungary is located at 16 Kacinczy Street. At number 41 (in the courtyard), the kosher delicatessen Dezsö Kövari seems taken right out of a film from the 1930s. The proprietress stands stone-faced behind her counter, on which an immense red slicer holds the place of honor.

A stroll through the somber streets with their peeling facades hints at the splendors of times past. The door of 16 Sip Street is shaped like a menorah, while that of number 17 hides a stylized tree of life. The Neolog community’s headquarters are located at 12 Sip Street. The cultural center itself is found near the opera.

A required stopping place for a bite to eat used to be the Fröhlich Bakery , where you were able to sample exquisite Kindli and Flodni, Purim cakes made with poppy seeds and nuts. It has closed after the Covid. Taking Dob Street up to Klauzál Square, you will find Kadar restaurant , a cult hangout. A Yiddish proverb maintains that “it takes two to eat a chicken: me…and the chicken”.

This is exactly the ambience that prevails in this cramped bistro where you will have to share your table with the regulars. On the wall hang photographs f famous actors, most notably of Marcello Mastroianni, who stopped here for a hearty meal. Students and artists come to savor, at ridiculously low prices, Jewish cuisine…Hungarian style. While they do serve a copious cholent here, a shabbat dish made from red beans, there is nothing kosher about it. They serve the dish on Fridays and Saturdays, embellishing it with bacon or smoked breast; it is also offered with roasted goose or chicken. On the menu, other Jewish specialities -boiled beef with cherries- line up alongside undeniably Magyar paprika stews. Kadar is a temple of gastronomic assimilation.

The history of Cholent, traditional shabbat dish

“[a dish of] Central European Jewry, the best, the most satisfying: made especially for the poor, who could keep it in their kitchens for three or four days, or even longer, without fear if its going bad.

It was a concoction of dried beans, eggs, rice and goose-flesh (sometimes beef or lamb instead), and was cooked in the oven in a big saucepan, its lid fastened wit fine string to which was fastened a label bearing the name of the family who owned it. This was because the sciolet needed a whole night’s cooking and was therefore placed in the big communal oven. No private house could burn and keep watch over a fire for that length of time.

Giorgio and Nicola Pressburger, Homage to the Eight District: Tales from Budapest, Trans. Gerald Moore (London: Readers International, 1990).

Not far from the Jewish quarter, Andrássy Street is worth a stroll for its splendid mansions, two-third of which were inhabited by Jewish families at the turn of the twentieth century. At number 23 lived the banker Mor Wahrmann: a rabbi’s grandson, he became president of the Chamber of Commerce and Industry, and the first Jewish deputy elected to Parliament in 1869. He advocated emancipation, but for the leisure class alone.

In the footsteps of Jewish artists

Throughout the city, Jewish artists have left their mark. We should not overlook Miksa Róth , who designed the stained-glass windows for innumerable buildings, including the Gresham Palace, the magnificent Franz Liszt Music Academy, and the Museum of Agriculture.

The architect Béla Lajta cleverly blended Art Nouveau, Jewish motifs, and Hungarian folk style in his buildings: gates were often adorned with menorot, six-pointed stars, and biblical motifs like the tree and the serpent, or Noah’s Ark. The staircases he designed for the Institute for Neurological Research (founded in 1911) resemble towers. At the top, a complex structure of wooden beams is reminiscent of Transylvanian architecture. The Institute for Handicapped Children and the hospital on Amérikai Street are two other remarkable examples.

Latja also designed several mausoleums for the Rákoskersztúr cemetery . The mausoleum of the Schmidl family, for example, is impressive; its decor -majolica and mosaics made of glass and marble -was inspired by the sepulcher of Galla Placidia in Ravenna.

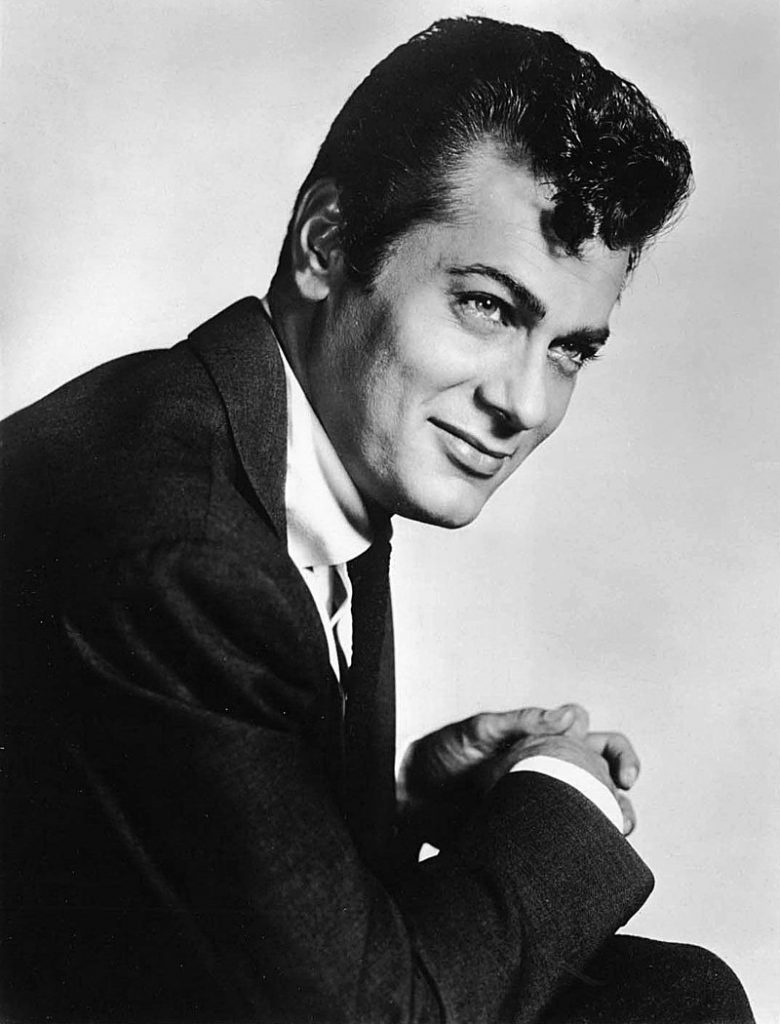

Tony Curtis

Bernard Schwartz, better known as Tony Curtis, financed the reconstruction of Jewish life in Budapest with Estée Lauder and the Hungarian government when democracy returned in the 1990s.

Emmanuel Schwartz, the tailor father of the great actor of Defiant Ones, Some Like It Hot and Spartacus, was born in Mateszalka in Hungary. His mother, Hélène Klein, was born in Slovakia. They started a family in New York, where Tony was born. They lived in great poverty there, and were also subjected to anti-Semitism. In 1984, Tony Curtis recounted in a BBC documentary how his father felt he had escaped his difficult circumstances by going into a synagogue on feast days, his son looking at him with emotion.

After a difficult childhood, he joined the navy in the aftermath of the attack on Pearl Harbor. After the war, he studied theatre in New York and began his magnificent career with Universal. Reconnecting with his origins, he took part in tourism promotions in Hungary and financed the restoration of the Dohany synagogue. A year after his death, in 2021, his daughter, Jamie Lee Curtis, financed the restoration of the Mátészalka synagogue. The city has opened a Tony Curtis museum and is organising the Tony Curtis International Film Festival from 19 to 21 September, with the aim of encouraging collaboration between Hungarian and international artists.

The earliest refugees from the Iberian Peninsula arrived in Ragusa (present-day Dubrovnik) at the end of the fifteenth century, at a time when the republic, still under nominal supervision by Hungary for a few more decades, had reached its apex.

The early years were tumultuous: forced exile in 1515 was followed by a return several years later. With reinforcements of fellow Jews coming in through Greece and Albania, the city’s small Jewish community would be recognized in 1538 as Univeritas Haebroru or Università degli Ebrei (Hebrew University), since Ragusa’s education leaders used Latin as much as Italian as an official language. Doctor Amatus Lusitanus, of Portuguese origin (as his name suggests), wrote seven books during this time describing the 700 illnesses he had treated.

The ghetto was created several years later, in 1546, on Zudioska Street, enclosed by gates at both ends. A 1745 census reveals, however, that 78 people were living in the ghetto’s nineteen houses while 103 others were permitted to live outside. During this period, moreover, Jews earned a status near that of the rest of their fellow citizens, as proven by their passports: the passports were printed in Italian for voyages across the Mediterranean and in Serbian for trips toward the Ottoman lands.

The size of the Jewish community remained steady until the Second World War, when more than 1000 Jews from Yugoslavia and other countries under the Reich’s domination flooded into the Italian zone. Soon transferred to internment camps on the islands off the coast, several hundred Jewish prisoners managed to escape before the Italian debacle in September 1943 and the region’s subsequent seizure by German troops. Only a few dozen people of Jewish origin still live in Dubrovnik, where the presence of tourists is often necessary to form a minyan at the synagogue.

After the Second World War, about thirty Jews left to live in Israel. This was the number of Jews who lived in Dubrovnik in 1969. The small number of Jews in the city and the Dalmatian region forced the city’s rabbi to officiate in the surrounding area. Today the small remaining community is part of the Federation of Jewish Communities in Croatia, based in Zagreb.

The synagogue

The three-story synagogue, whose origins date to the fourteenth century, has served as a house of worship since 1408. In fact, it is one of the oldest Sephardic sites in the world. It can be distinguished from the other house of Zudioska Street only by its slightly larger second-story windows with their traditional Arabic trim. In the seventeenth century, the synagogue benefited from passageways through the other houses on the block, which allowed ghetto dwellers to come and go without breaking curfew.

Among the religious artifacts that managed to remain hidden during the war are three scrolls of the Torah dating back to the first Sephardic immigration. A little under 24 inches wide, their outer layers are made from linen and rolled lengthwise, knotted in a particular way called “Ragusa point”. The scrolls also bear the names of their likely donors: the Terni, Maestro, and Russi families. A silk, cotton-padded bedspread of undeniably Iberian origin is also on display at the synagogue. Seriously damaged by a Serbian bombardment during the 1992-95 war, the synagogue has since been restored.

The cemetery