Created in 1879, the Jewish cemetery in Dakovo possesses the unique feature of containing individual burial sites for victims of the Shoah. A total of 566 Jewish victims of Dakovo’s Ustashi concentration camp, murdered in 1942, are buried here. A collective monument has been erected as well. The cemetery is located on the ulica Vatroslava Doneganija near the municipal cemetery.

The illuminated registry of the burial society (Hevra Kadisha) of Dakovo, which dates back to 1860, is preserved in the Jewish Historical Museum of Belgrade.

In 1847, fifty or so families helped found the community in Osijek, Slavonia’s main city. A school and synagogue were quickly built, presided over by Rabbi Samuel Spitzer, author of religious, cultural, and historical books. His son, Hugo Spitzer, became a pioneer of Zionism in Yugoslavia at the turn of the twentieth century.

The community consisted of 2,600 members in 1940, 90% of whom were killed in the Jasenovac, Djakovo, and Loborgrad camps in Croatia, as well as Auschwitz.

At the headquarter of the city’s small Jewish community, a museum houses the remains of objects rescued from the main synagogue, destroyed during the war. In Osijek’s main square, there is a monument dedicated to the victims of the Shoah. A Jewish cemetery can also be found in the Lower Town of Osijek and a Jewish cemetery in the Upper Town.

After the war, 610 Jews remained in Osijek and the region. Two-thirds of them migrated at the end of the 1940s. A monument to Jewish fighters and victims of Nazism was erected in 1965 in a square in Osijek. The monument was created by Oscar Nemon, a former resident. At the turn of the 21st century, 200 Jews still lived in Osijek. A former synagogue in the Lower Town was converted into a church. A plaque at the entrance recalls its former function.

In September 2025, numerous Jewish cultural events were organised in the city of Osijek to bring together people from all walks of life and familiarise the local population with Jewish cultural heritage. Among the events presented was a concert by Ladino singer Nani Vazana.

In 2025, approximately 150 Jews remain in the city of Osijek. Nevertheless, this community is very active, spearheading European Days of Jewish Culture in Croatia and participating with Jewish institutions in other Croatian cities, as well as in Serbia and Bosnia and Herzegovina.

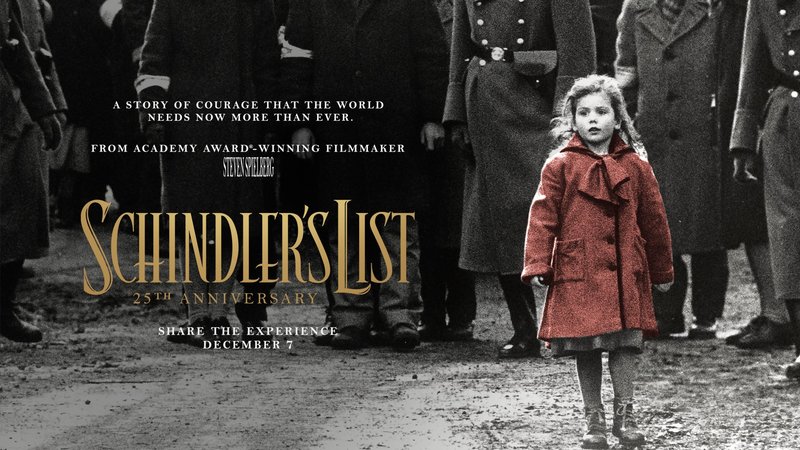

One of Osijek’s most prominent figures is Branko Lustig. Born in this town in 1932, he was deported during the Holocaust to Auschwitz. Most of his family members were murdered. After the war, he studied acting in Zagreb.

Lustig later became a director and producer, participating in these roles in about 100 films, and was particularly active in promoting Croatian cinema. Among the major films he produced were Sophie’s Choice (1982) and Gladiator (2000). Residing for the most part in Los Angeles, in his later years he spent increasing amounts of time in Zagreb, where he was made an honorary citizen of the city for his « great contribution to the culture of a democratic society, to movie art and to understanding between peoples ».

Branko Lustig, Gerald R. Molen and Steven Spielberg co-produced Schnidler’s List (1993). At the Academy Awards ceremony, Spielberg stressed the need to listen to the voices of survivors and encouraged teachers to welcome them to share their experiences with students.

When Branko Lustig took the podium, he began by recalling the number tattooed on his arm during the Holocaust, and then said, with great emotion « I’m a Holocaust survivor. It is a long way from Auschwitz to this stage. I want to thank everyone who helped me come so far. People died in front of me in the camps. Their last words were ‘be a witness of my murder’. Tell to the world how I died. Remember. Together with Jerry, by helping Steven make this movie, I hope I fulfill my obligation to the innocent victims of the Holocaust. In the name of the six million Jews killed in the Shoah and other victims of the nazis, I want to thank everyone for acknowledging this movie. »

In 2011, Branko Lustig participated in the March of the Living, celebrating his bar mitzvah at age 78 in front of the camp where he was deported and from which he was liberated at age 13. The New York Times has released a video report, which can be seen at this link, showing Branko Lustig repeating the prayers before arriving at the site of his painful past.

His American success never made him lose his sense of values. Thus, answering Interviewsmagazine about where his house is actually located, Branko Lustig spoke about Zagreb. That despite the Shoah, returning to the city where he studied film is important to him. That he knows the places and the people there, marked by the human touch and the sincerity of the relationships. That he does not forget but forgives, speaking to the new generations of Zagreb. He directed the Zagreb Jewish Film Festival, not for the 300 Jews who still live in the city, but as he says, to “share a spirit of tolerance and learn from the past so that it does not happen again”.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Varazdin is an important trading town located between Vienna and Trieste. The Jewish presence probably dates from the 18th century, mainly from Moravia, Hungary and Austria. They worked there mainly in the cattle trade. Among the town’s most prominent figures was Mirko Breyer, a patriotic author and book collector, who donated many works to national institutions.

The synagogue was opened in 1861. At that time there were about 500 Jews in Varazdin. During the Holocaust, most of the Jews were killed. After the war, the survivors tried to establish a new community. The synagogue was nationalised in 1945 and repaired the following year. It has since been converted into a cinema. The building was also renovated in 1969, in a communist style, and again in 2021, more faithful to its original style.

The city also includes a neglected Jewish cemetery dating back to 1810. The cemetery is located on the main road to Koprivnica.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

The Jewish presence in Karlovac probably dates back to the mid-19th century. A synagogue was built in Karlovac in 1870. It served the community until 1960, when it was destroyed. A commemorative plaque has been placed on the building where it once stood.

Karlovac counted around 500 Jews before the war. Karlovac’s Jewish cemetery has been the target of fascist vandals, who have painted swastikas and slogans glorifying the Ustashi regime.

It contains around 200 graves. The cemetery is located at Velika Svarca, near the military cemetery.

Zagreb is the capital of Croatia. The Jewish presence probably dates back to the 10th century, originating from surrounding areas but also from Spain and France. A place of prayer was mentioned at the end of the 15th century. Following the expulsion of 1526, the Jews were not able to return until two centuries later.

About 50 Jewish families from Bohemia, Moravia and Hungary lived in Zagreb in the mid-19th century. A synagogue, built by Franjo Klein, was opened in 1867. The chief rabbi of the city for fifty years was Hosea Jacoby. A Jewish school, a Talmud Torah and a home for the elderly were built at this time. Among the town’s Jewish personalities was Jacques Epstein, founder of the first Croatian charity, the Association for Humanism. Many local Jews also played a role in the Croatian patriotic movement, including Joshua Frank. Other prominent figures in the city were the doctor Mavro Sachs, the painter Oscar Hermann and the pianist Julius Epstein.

12,000 Jews lived in Zagreb at the beginning of the Second World War, some of them refugees from the surrounding countries. The Holocaust claimed many victims in Zagreb, including persecution, murder and deportation.

The Jewish community tried to rebuild itself after the war. The Jewish population of Zagreb was 1200 in 1970. The number declined to about 1000 at the turn of the 21st century. It constitutes the majority of Croatian Jews.

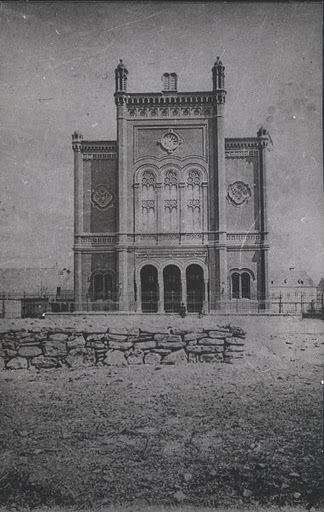

Built at the turn of the twentieth century by architect Franjo Klein, the Grand Synagogue of Zagreb was entirely destroyed in 1941 along with Croatia’s approximately thirty other active synagogues. Today, a far more modest establishment, located on the same site as where the Jewish Community Center headquarters used to be, serves as a place of worship. Besides a collection of religious artifacts, the community’s offices also house one of the largest Jewish libraries in the region of the Balkans, which has collected over 20,000 volumes, some of which date back as far as the fifteenth century.

The Zagreb Jewish Museum was created in 2016 to celebrate the community’s 210th anniversary. It features mainly ritual objects used by families throughout this two-hundred-year history, allowing visitors to rediscover Jewish life through the ages. More than 150 objects in all, including ancient Torah scrolls and books dating back to the 16th century.

Built 120 years ago on the city’s north side, the Mirogoj cemetery rivals the most beautiful in Europe. Its sizable Jewish section has the unique quality of featuring Christian and non-Christian tombs side by side. Over time, many Jewish graves were sold to Christians after their leases expired due to the disappearance of entire families during the war, and this accounts for the unusual arrangement.

Piran is a former possession of the City of Doges, which explains its Venetian atmosphere. It contains some beautiful architecture, including a replica of the Campanile in the Piazza San Marco.

This charming little coastal town has preserved its medieval ghetto square, Zidovski Trg, which can be entered through an arcade. The square is surrounded by several multistory houses that undeniably resemble those of the Venetian ghetto.

In the 1980s, the town of Piran was largely renovated. A Jewish Square Quarter has been named in the Old Town, in remembrance of the former Jewish presence. Some historical sources indicate that Saint Stephen’s Church was built on the site of a medieval synagogue.

Nova Gorica was divided between Italy and Slovenia after the Second World War. It is on the Italian (Gorizia) side that one should look for major evidence of a past Jewish presence.

In the Slovenian section, however, there is a Jewish cemetery dating back to the fourteenth century. With one and a quarter acres of surface area, it contains nearly 900 gravestones, the oldest of which date to the seventeenth century, and they are still legible. The most recent tombstones date from the Second World War. The grave of the philosopher and painter Michelstädter, who died in 1929, is found here as well.

The cemetery has no caretaker, though it is apparently kept up regularly thanks to the gracious efforts of the Italian-Jewish community. The cemetery is located in the Rozna Dolina (Valley of Roses), several hundred yards from the main border passage point.

A ghetto was created in the city in 1648. In 1777, the city also welcomed many Jews driven by Venice from the small surrounding villages that did not strictly speaking have a defined and demarcated ghetto. The Jewish community thus grew to reach the number of 270 members in 1788.

Most of the sites referring to the Jewish presence at the time are now on the Italian side.

The Lendava city council is working to renovate the old synagogue, built in 1866, and turn it into a cultural center featuring a permanent exhibition on local Jewish history. Seriously damaged by the Germans during the war, the synagogue was later sold to the city by the Federation of Yougoslav Jewish Communities, which then used it as a warehouse. The former Jewish school, active until the 1920s, was located next to the synagogue.

The Jewish presence in Lendava probably dates from the end of the 18th century with the arrival of Jews from Hungary. They first met in a house to pray, then rented a hall in 1837, where the community met regularly. Six years later, the city’s first synagogue was built.

Renovation work on the new synagogue began in 1994. Few of the original elements remain, except six metal pillars and part of the stairs. The city therefore asked the Jews of Lendava and surrounding villages to participate in the renovations in order to come closer to the spirit of the original construction.

In April 2019, President Borut Pahor paid tribute to the victims of the Holocaust in Lendava in an official ceremony in the company of survivors. The president also laid a wreath at the Dolga Vas cemetery, the largest Jewish cemetery in Slovenia, together with the mayor of the city, Janez Magyar.

The Jewish cemetery , which dates back to the late nineteenth century, was renovated in 1989 after vandals damaged around 40 gravesites. In all, it contains 176 graves and features a memorial to the victims of the Shoah put up shortly after the war by survivors. It is located near the village of Dolga Vas, on the road leading toward the Hungarian border.

The Jewish cemetery of Murska Sobota no longer exists; it was demolished in the 1990s. The site features, however, a small monument erected in memory of the city’s Jews murdered during the war.

A city that has existed since at least the Roman period and was destroyed in the conflict with the Ottoman Empire, Murska Sobota was home to the largest Jewish community of the interwar period.

The city has had at least two synagogues in its history. The first was located in a house belonging to an individual. It dates from 1860. The building was destroyed in 1995. Another, built by architect Lipot Baumhorn, was built in 1908 and demolished in 1954. A building bar has since replaced it.

The Jewish settlement in the medieval fortress of Maribor near the Austrian border dates back at least to the thirteenth century. After their expulsion by Austrian emperor Maximilian I, Maribor’s Jews headed for Italy and Hungary. The Morpurgos, one of the most famous families in Trieste, Split, and even Gorizia, was among them: their names derive directly from Maribor, their city of origin.

The Regional Museum of Maribor features the tomb of the first rabbi known to have officiated in the city, a certain Abraham, who died in 1379.

The former Jewish district, located in the southwest section of the old city near the outer walls, has its own Street of the Jews. The synagogue here was restored and also hosts a memorial to the victims of the Shoah. The building, whose dimensions measure 65 ft. x 39 ft., was converted into a church in the sixteenth century, following the expulsion. The only remnants today of its use as a synagogue are a wide recess for the Ark of Covenant as well as a number of fragments bearing Hebrew inscriptions.

You will also find the “Jewish Tower” here, now a photo shop. Not far from the synagogue, it most likely owes its name to its role in defending the Jewish quarter during attacks against the city.

The synagogue is the third oldest in Europe still standing. On January 17, 2019, the Maribor synagogue commemorated the Holocaust by presenting an exhibition on Russian officer Alexander Pechersky, who led the uprising in the Sobibor concentration camp. The Russian film Sobibor (2018) was also shown here on this occasion. The Slovenian Ministry of Culture, as well as Russian institutions took part in the organization of the remembrance day.

The only remaining traces of a prior Jewish presence in Ljubljana are the names of two narrow streets in the city center, Street of the Jews (Zidovska ulica) and Passage of the Jews (Zidovska steza), the place of the medieval ghetto until the 1515 expulsion.

The remains of a neighborhood of about thirty houses have apparently been found beneath the Baroque buildings here, constructed in the seventeenth century atop the medieval foundations.

The Jewish presence in Ljubljana probably dates from the 12th century. According to historian I.V. Valvasor, following its destruction by fire, the Jews renovated the city’s synagogue in 1213. A ghetto consisting of a few dozen houses probably stood in what is now Jurcicev Square. The Jewish population never exceeded 300. The community had a school and a beth din. The district has since been completely rebuilt, in the 17th century and then in the 19th.

Expelled from the city in 1515 by Emperor Maximilian, the Jews could only return from the regency of Joseph II. The 19th century was more welcoming, with the Jews resettling and obtaining emancipation in 1867. In 1910, there were 110 Jews in Ljubljana, having no full community and being attached for religious services to that of Graz in Austria. When the city was integrated into Yugoslavia, the community was attached to that of Zagreb.

The synagogue was probably located at number 4 Zidovska steza street. The Jewish Cemetery is located on a plot of the Zale Municipal Cemetery . About twenty tombs, very modest. In the center of the cemetery is a monument in memory of the victims of the Shoah. Which was erected in 1964.

Robert Waltl, a theater manager who later discovered his Jewish origins, began in 1999 to renovate an abandoned building to accommodate a theater. Approached by Jewish artists who no longer had a synagogue since the closure of the last one in Ljubljana, he ceded a floor of the theater to transform it into a Jewish Cultural Center including a Jewish museum, a place of remembrance of the Shoah and a synagogue. Rabbi Ariel Haddad, based in Trieste but touring the Jewish communities in Slovenia every week, holds prayers there regularly.

Established in 2013, the Jewish Community Center of Ljubljana aims to share the diversity of Judaism, with an emphasis on culture and understanding, opening its doors to all Slovenian Jews and tourists. It is based on three pillars: history through a museum tracing the history of Slovenian Jews from its beginnings to the Shoah, religion in its synagogue and its festival hall, and finally culture with a place dedicated to workshops and exhibitions. The synagogue was opened in 2016. Services are held there for Shabbat and major holidays.

Here’s our interview with Robert Waltl, Director of the JCC Ljubljana.

Jguideeurope: Are there educational projects proposed by the Center, and how is the city of Ljubljana participating in the sharing of Jewish culture?

Robert Waltl: The very idea of establishing the JCC grew out of the realization that Slovenian children (and adults) know practically nothing about the presence of Jews on the present-day territory of Slovenia and that their knowledge about the Holocaust is narrowed down to the events that took place elsewhere than in Slovenia. So, after conducting surveys among schoolchildren, we decided to start various educational programs and to erect a colonnade in front of the houses of Holocaust victims in Ljubljana, Lendava and Murska Sobota.

The first were the educational mornings about the Holocaust, which we carried out within the Festival of Tolerance, mainly with Holocaust survivors, double Oscar winner Branko Lustig and rescued Jewish boy Tomaž Zajc, and partisan survivor Dr. Anica Mikuš Kos. Various other experts also take part in the talks. The principle was that we first watched together a film or a theater performance on the subject of the Holocaust and children in the Holocaust, such as “Villa Emma”, “Run Boy Run”, “Belle And Sebastien”, “Framed: The Adventures Of Zion Man”, “Fanny’s Journey”, “The Jewish Dog”,… After the performance there was a discussion with a Holocaust survivor and various experts.

Shalom – Playful Learning about Judaism is a program enabling us to explain the basic concepts of Judaism, holidays, beliefs, life and death. The programs are tailored to age groups. We also have special programs for adults (Slovenian and foreign visitors) on the history of the Jewish presence on the territory of today’s Slovenia. In addition to theater and film, we often organize various exhibitions, concerts and lectures alongside our educational programs.

The City of Ljubljana cooperates with us in the Stolpersteine project by installing paving stones for the victims of the Holocaust and raising awareness of the Holocaust in Ljubljana. The City of Ljubljana also supports some of our theater projects, such as “The Jewish Dog”, “The Diary of Anne Frank”, “Amsterdam”… We are currently working with the City Museum of Ljubljana on the first permanent exhibition about the Holocaust in Ljubljana, which will be on display in our museum from September.

Rabbi Alexander Grodensky organizes thematic lectures on Judaism and religion and teaches Torah for the members of the community. One of the problems encountered is that the Jewish Cultural Center does not have the permanent support of the city or the state, which do not recognize the importance of our Center for the citizens and residents of Slovenia.

In times of intolerance and renewed war in Europe, our mission becomes even more important. We also appeal to the world Jewish public to help us, because a small Jewish community like ours in Slovenia cannot bear the financial burden alone.

Can you share a personal anecdote about an emotional encounter with a visitor or researcher during a previous event?

In the years before the Corona, between 4 and 5,000 visitors came to our center. We have hundreds of moving accounts from our visitors who have recognized our efforts and tremendous efforts in trying to revitalize Jewish life in Slovenia, as well as our Holocaust awareness programs. If before 2013 there was not even a single memorial to the Jewish presence in the history of the city, today we have a memorial plaque on the site where the medieval Ljubljana synagogue stood until 1515. We also have 68 stolpersteine for 68 victims of the Holocaust.

In September, we are opening a stolperschwelle for another 150 Jewish refugees, mostly expelled from NDH-Croatia in 1941. In the Museum, before the beginning of the renovation, we had three powerful art installations dedicated to the Slovenian victims of the Holocaust, which evoked an immense power of remembrance and emotion in the visitors.

Along with the stolpersteine, there was also an art collection of portraits “Undeleted”, by the intermedia artist Vuk Čosić, which brought the faces of our ancestors back to life from the memory of oblivion. Of course, the atmosphere of the 500-year-old, half-ruined house in which we worked until the renovation for 2 years now with our own funds also contributed to the feeling. In addition to a small museum, we will open a memorial synagogue dedicated to the Slovenian victims of the Holocaust, managed by the Liberal Jewish Community of Slovenia.

The building will also house the exhibition dedicated to the Holocaust in Ljubljana, a Judaica collection, a meeting room, and library, as well as common spaces shared with the Mini Theater, a café, and guest residences.

Guests have often shown their appreciation through their donations, which have made it a little easier for us to cover our running costs. We hope that with the renovation of our center and new activities, more visitors from all over the world will come to visit us every year.

The region’s sovereigns, the Esterházy dukes of Hungary, granted the Jews special protection within the seven districts of Burgenland. Since 1670, the region has been one of the most important Jewish cultural centers of central Europe.

The Jewish presence in Eisenstadt probably dates from the 14th century. A community finding refuge there from other cities but also expelled from it. But Eisenstadt is best known for having hosted one of the most flourishing communities from the 17th to the 19th centuries, since their return in 1626. Subject to fiscal pressures, the Jews were able to live there in relative freedom. Thanks in particular to the support of the Estherhazy family and prominent figures such as Samson Wertheimer (a rabbi who built a beit hamidrash), the yeshiva of Meir Eisenstadt, and the one headed by Azriel Hildesheimer.

The Jews were expelled from Eisenstadt following the Anschluss of 1938. Most of them then settled in Vienna. The synagogue was destroyed, and the Jewish cemetery vandalized. A handful of Eisenstadt Jews survived the Holocaust. Many Jewish manuscripts from the Wolf Museum were housed after the war in the Landesmuseum Burgenland .

The Austrian Jewish Museum , opened in 1972, displays numerous documents and objects, recalling this region’s highly unusual history. A visit not to be missed.

Interview with Christopher Meiller, curator and educator at the Austrian Jewish Museum

Jguideeurope: How was the Jahrzeit project materialized in the Museum?

Christopher Meiller: The “Jahrzeit project“ was enabled through an amazing discovery, when in the 1990s, 750 Jahrzeit plaques from the region were found accidentally at the attic of the museum.

Presumably they had been put there long ago, and now the museum was able to make these unique items, dating from the 18th century up until 1938, accessible to the public by adding them to the synagogue next to the exhibition rooms.

All of this is accompanied by explanatory information and translations of the plaques.

Can you present us some of the other objects shown at the permanent exhibition of the Museum?

A particularly relevant and certainly unique item is the Torah wimple of the famous rabbi Akiva Eger the Younger, a leading rabbinical authority of his time, coming from Eisenstadt. Most interesting is also a highly unusual Seder plate from the 18th century, full of remarkable and sometimes baffling details. And then, of course, there is the synagogue, not only amazing aesthetically but also the oldest synagogue still in use in Austria.

Mauthausen was classified by the SS administration as a “Category 3” camp; this category of camp corresponded to the harshest possible treatment. The prisoners sent here were designated “return undesirable” and destined for “extermination through work”.

All activities in the camp gravitated around the stone quarry and the construction of tunnels in the infamous adjoining camps of Gusen, Melk, and Ebensee. The Mauthausen camp was liberated on 5 May 1945 by the American Eleventh Armored Division.

A memorial ceremony takes place every year on that date. Twenty countries have participated in events commemorating the murder of 150,000 people here during the Second World War, one-third of whom were Jewish.

The history of Vienna’s Jewish community can be divided into several distinct periods, with the community itself settling in two specific neighborhoods: in a section of the city center in the First Bezirk and in Leopoldstadt in the Second Bezirk.

In the Middle Ages, the first Jewish community in Vienna established itself in what came to be known as the “Judenstadt” in the heart of the city not far from the cathedral, inside a perimeter roughly delimited by present-day Seitenstettengasse, Hoher Markt, Jordangasse, and Judenplatz.

The Gothic-style synagogue, similar to the Alteuschul in Prague, was first mentioned in 1294 as the Schulhof, named after the spot on which it was built (now the Judenplatz) in immediate proximity to the Court.

In addition to the Judenplatz, there is a nearby different square called Schulhof, bordered by a Gothic church resembling the former synagogue and perhaps an exact replica of it, designed after its destruction in 1421. Between 1360 and 1400 the Jewish community ranged from 800 to 900 people, representing 5% of Vienna’s total population. In 1421, however, they were all either expelled or forced to convert.

In 1624, the Jews were granted a new neighborhood, the Unter Werd, located along Taborstrasse in present-day Leopoldstadt, on the other side of the Danube. A new syngogue was built there; Leopoldskirche church stands on the site today. The Unter Werd ghetto, which included 132 houses, offered the Jews a certain amount of protection until it was destroyed and its residents exiled in 1670.

Beginning in 1781, with Joseph II’s edict of tolerance, Jews settled in Vienna once more. In 1826, a new synagogue by architect Josef Kornhäusl was built on Seitenstettengasse, marking the community’s effective return to its historical center of Jewish life of the Middle Ages. In 1858, another synagogue, the Leopoldstädter Temple, was built across the Danube not far from where the former Unter Werd ghetto once stood in Vienna. This attracted Jewish settlers to the district, later called Mazzesinsel, or “Matzoh Island”.

Here and there along its streets, you will come across plaques marking former Jewish community establishments. The Leopoldstädter Tempel stood on the street bearing the name Tempelgasse, at number 5.

A plaque a four large columns by architect Martin Kohlbauer evoke the former synagogue. In its place today is the ESRA , a center dedicated to counseling the victims and witnesses of the Shoah and uprooting.

At number 7 on the same street sits the Sephardic Center , which brings together associations of Jews from Bukhara, Georgia, and their respective synagogues. Before the war the Turkish Temple, for the Jewish community from the Ottoman Empire, resided on Zirkusgasse (Circus Street). Built in 1885 in Moorish style, it was destroyed in 1938.

Residential housing was built in its place in the 1950s. A strange plaque declares: “Gesunde Wohnungen, glückliche Menschen” (clean apartments, happy people), while another , smaller one, hidden beneath a balcony, notes: “The Turkish Synagogue was located here”. The Orthodox Temple Polnische Schul, constructed with three naves, stood at 19 Leopoldgasse but was also destroyed on 9 November 1938.

Since the 1980s, the Jewish community has once again concentrated its activities in this district. So much so, that in 2025 this district hosts 19 of the 21 synagogues of the city, except for the Stadttempel and another one which is located in the 19th district.

Admittedly, these synagogues are relatively small, in dilapidated buildings and what appear to be refurbished former flats. A walk from Taborstrasse through the district reveals the presence of Jewish life, especially in the southern part. Synagogues of different denominations and rites.

The Nestroyhof Hamakom Theatre is an important place of Jewish culture in this district. It is housed in a magnificent Art Nouveau building by the architect Oskar Marmorek. The Nestroyhof Theatre hosted various forms of Viennese popular theatre, as well as Yiddish plays.

It tried to continue despite the measures imposed by the Nazis in 1938. Nevertheless, the venue was confiscated in 1940. Only in 2004 was it able to reopen as a theatre. The venue added the word “Hamakom” (meaning “the place” in Hebrew), with plays from different backgrounds being presented, including Israeli ones.

Leopoldstadt also has a chabad centre, kosher grocery shops and many restaurants, such as Mea Shearim, Novellino and Bahur Tov (Hebrew for “good guy”). Beware, most of these restaurants have as a first quality to offer kosher food to those who want it. Because they often offer everything and look more like fast food.

On the other hand, one will be surprised to see the Mediterranean and especially Israeli imprint in the good classic Viennese restaurants. With shakshuka as a recurrent dish! This would probably have pleased Theodor Herzl, who was originally buried in Vienna and has a square named after him near the Stadtpark in the city centre.

Anecdote that allows us to make the transition to the places to visit in the city centre. In particular, the Jewish Museum, the Judenplatz Museum and the synagogue.

The Jewish Museum

Vienna, site of the world’s first Jewish Museum in 1897, opened the current one in 1990. This museum , whose purpose is to act as a link between Jews and non-Jews, also serves as a window on the rich but lost world of Viennese Judaism.

The first floor houses two permanent exhibitions. The first displays objects of Jewish liturgical life, while the second -the creation of New York artist Nancy Spero- illustrates Vienna’s Jewish history.

Panels explain the Jewish history of Vienna and the slow recognition of the crimes of the Shoah by the authorities. But also the pleasant life of the Jews in other periods of the city’s history. Then, photos and objects from different periods of this life.

The second floor is for temporary exhibits, and the third provides a retrospective on Jewish life in Austria through twenty-one painting. The fourth floor, in a room called the Schaudepot, “depot expo”, is given over to hundreds of religious objects recovered after Kristallnacht. It resembles the back room of an antique shop.

The library here tops those of all other Jewish museums in Europe. It preserves 25000 volumes in German, Hebrew, Yiddish, and English. Located at the museum entrance is a bookstore well stocked in catalogues and texts (in German). On the same floor, Teitelbaum Café, among the city’s best, serves Austrian kosher wines, Viennese pastries, and vegetarian dishes.

The museum’s small shop has the rare feature among museums of offering souvenirs at not too crazy prices. And also to buy old catalogues of previous exhibitions, notably the very successful ones about Hedy Lamarr, the iconic Viennese actress, or “Love Me Kosher” on the different representations of sexuality in Judaism.

Judenplatz

A monument by London artist Rachel Whiteread commemorating Austrian Jews exterminated during the Shoah was placed in the Judenplatz (former Schulhof) in October 2000. The piece consists of a square, closed room, the outer walls of which supports shelves loaded with books.

The Judenplatz Museum in the Misrachi House is located behind the monument and has also been open since 2000. Its focus is the Jewish quarter of the Middle Ages, particularly the founding of the medieval Gothic synagogue (Or Zarua), rediscovered in 1995 during an archaeological dig.

Two videos and computer-animated displays provide information about medieval Jewish life. At the museum entrance, a room equipped with computers allows visitors to look up the names of 65000 victims of the Shoah.

In the city there is also the Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies . This institute is named after the Nazi hunter who wanted to give researchers access to his archives and worked for the last years of his life in Vienna.

It allows the study of the mechanism of hatreds linked to racism and anti-Semitism and provides pedagogical help to researchers and teachers in Austria, as well as around the world.

The Synagogue of Vienna

The Stadttempel , Vienna’s synagogue of 1826 built by architect Josef Kornhäusl, was the only temple that avoided destruction during Kristallnacht. Kornhäusl, highly respected in his time, specialized in theaters; not surprinsingly, then, the Stadttempel was designed like a small theater or Italian-style Baroque opera house, with a circular shape, a stage, three balconies, wings, and a foyer.

It lacks only dressing rooms and ushers. The setting, but also the talent of its cantors even motivated Richard Wagner, who was reluctant to appreciate this kind of atmosphere, to come among the faithful and listened to their music.

There are several reasons why the Stadttempel was not destroyed, unlike the fifty or so others. First of all, according to the customs in force at the time of its construction, Jewish places of worship had to be discreet, not visible from the street, and therefore sheltered behind a façade. Burning this synagogue would have caused havoc in the whole street, as it could not be a localised fire. Moreover, the Nazis had set up shop in the building adjoining the synagogue, where they kept the archives concerning the Jewish population and Adolf Eichmann’s office on the fourth floor.

The Judengasse , a little street linking the Seitenstettengasse to the Hoher Markt, was a main street throught the Jewish quarter of the Middle Ages, as it names indicates.

Other Famous addresses

It is not possible to fully grasp Jewish Vienna without stopping by the haunts of the major Jewish intellectuals who helped make Vienna one of Europe’s most modern capitals at the turn of the twentieth century. These figures include Sigmund Freud, of course, as well as Arnold Schönberg, Joseph Roth, and Martin Buber.

The address 19 Bergasse is legendary. This was Freud’s house , a spot of cult interest for all those fascinated by the history of psychoanalysis. While the furniture is original, his famous couch was moved to London when he emigrated there in 1938, a year before his death.Freud’s house features a museum including special exhibitions, the Library of Psychoanalysis, and archives.

Born in 1874, Arnold Schönberg founded the Vienna School along with Alban Berg and Anton Webern; he was a composer of twelve-tone music.

After converting to Protestantism in 1898 (just as Mahler had converted to Catholicism, the “entry ticket to European culture”), he returned to Jewish faith in 1933 in Paris, with Marc Chagall as his witness.

He then emigrated to the United States, where he dies in 1951, aware that he would gain true recognition only after his death. The Arnold Schönberg Center opened in 1998, and it preserves manuscripts, scores, correspondence, and archives that are available for examination.

Founder of the “philosophy of dialogue”, militant, author, Martin Buber was born in Vienna in 1878. Although he spent his childhood in Galicia, he later returned to Vienna. Both perceived as an important figure in the history of zionism and in the reconciliation of cultures, Martin Buber left important writings. After moving to Israel, he pursued those goals. He died in Jerusalem in 1965.

On Rembrandtstrasse sits the house where Joseph Roth lived. Born in Brody, Galicia, in 1894, Roth completed his studies in Lemberg (Lvov) and Vienna.

The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was highly traumatic for him, both as a geopolitical event and on a personal perspective. Joseph Roth’s work blends social criticism with transfiguration of the Austrian monarchy. And the impacts on Jewish life on the shtetls of his childhood, caught betwenn historical changes and evolving situations regarding their freedom. Novels that made Roth famous include Job, the Story of a Simple Man (1930), The Radetzky March (1932), and The Emperor’s Tomb (1938). He died in exile in Paris in 1939.

While there were 200,000 Jews in the city before the war, in 2025 only 8,000 Viennese Jews lived there, mainly in the 2nd district.

In Vienna, as in many European cities, the exploitation of the 7 October pogrom by various forms of anti-Semitism has manifested itself in insults, threats and attacks. Examples include violent attacks on Rabbi Shmuley Boteach by Islamists in the street and on a 12-year-old child by his schoolmates, simply because they were Jewish.

During the late Middle Ages, the city of Trani was home to a significant minority population of Jews. This community reached a high point during the thirteenth century. The giudecca of Trani was compact in size, diverse in architectural character, and largely open to the city around it, which indicates a specific form of coexistence.

At the moment of its greatest physical expansion, we find in Trani a rabbinical school -ran by Rabbi Isaiah di Trani- that could attract Jewish students and scholars from all over the Mediterranean world. The expansion of the giudecca in the thirteenth century resulted from a combination of intellectual vigor and economic prosperity. Another element in this context was the encouragement and acceptance offered to the Jewish minority by Frederick II.

A sampling of documents from the archives indicates that the Jews of the South had frequent exchanges with this ruler, who was deeply involved in the day-to-day details of governance. Frederic II granted Trani’s Jews personal and commercial protection in perpetuo, in return for the payment of an annual tax.

Trani’s role as a center of mercantile activity for the entire region is mentioned by Benjamin de Tudela, who passed through the city around 1166. He wrote that “Trani [is located] on the sea, [in a place] where all the pilgrims gather to go to Jerusalem, for the port is a convenient one. A community of about 200 Israelites is there. It is a great and beautiful city.”

The activity of Trani’s Jews consisted mostly of long-distance trade and the dying of fabrics, especially silk. Archival sources also mention soap-making.

The thirteenth century was the period in which the most concentrated building took place in the Jewish quarter, including the two largest synagogues, the Sant’Anna and the Scolanova, the most important buildings visible in the giudecca today. The solidity, grandeur, and variety of building types found in the giudecca dating from that period speak of a wealthy community that enjoyed economic prosperity, access to power, and an optimistic view of the future.

The grand palaces that greet the visitor on entering the giudecca housed the wealthy families whose economic activities set the rhythm of daily life. The facades of impressive buildings such as the Palazzo Lopez show bugnato style stonework, the same used in the great Palazzi of Florence and Venice. To find such a large palace within an Italian Jewish quarter is unusual. Generally, Jewish houses in Italian towns were small in scale and densily clouded together. But there were only two or three such palaces in the giudecca of Trani, indicating that the number of very wealthy families was small. Elsewhere, the contrast between the grand houses and the more modest row houses lining the main street suggests a multilayered society accommodating various social and economic strata. A third type of house was attached to the synagogue and served as the home for the rabbi.

The quarter is anchored at its center by a complex of religious and communal buildings built around a large open space. The two largest synagogues of the quarter were built near each other in the thirteenth century. The Sant’Anna synagogue is unusual because it was conceived as a synagogue, and did not emerge from converted domestic space. It was also built with the intention of accommodating the entire community. The structure was converted into a church late in the fourteenth century, then abandoned. It was in ruins and recently renovated and turned into a museum. The inspiration of the design of this synagogue was the byzantine Church, with a main hall almost perfectly square, enclosed by four immense arches that support a dome.

Although the dome gives a sense of a great interior space, on the outside the synagogue is no taller than the surrounding buildings. This effect was intentional, to avoid making the Jewish house of worship taller than the edifices of Christians. A niche in the western arch held the tevah. Today the main doorway is found on the eastern wall, where the aron hakodesh would normally be placed. Another feature of this synagogue is the space beneath its main floor. The subterranean zone was excavated to allow for two additional levels where a network of rooms was constructed. What activities might have taken place in these rooms? A mikveh, perhaps, or a room for preparing the dead for burial.

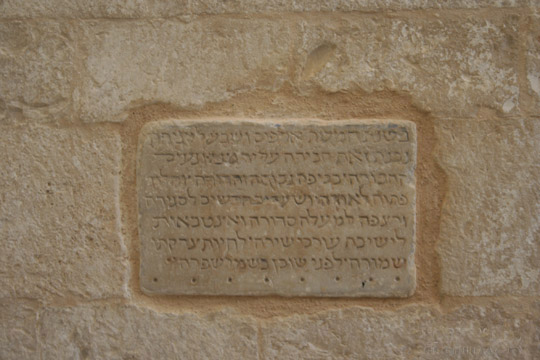

In the 1930’s was found a marble tablet embedded in the southern wall, probably placed there when the synagogue was built:

In the year 5007 after the creation

This sanctuary was built by a minyan

Of friends, with a lofty splendid dome and a window

Open to the sky, and new portals for enclosing it,

And a pavement on the upper floor, and benches,

For seating the leaders of the prayer, so that their piety

Would be watched over by the

One who dwells in the glorious heaven.

The great synagogue is a point of access into Tranesi Jews’ vision of themselves. The adoption of the Byzantine style construction was a statement about their self-perception as a cosmopolitan community having strong ties with the historical centers of Jewish culture further east. The facility in which the Byzantine church was translated later into Jewish idiom speaks of a community at ease in its diversity and open to non-Jewish influences in the building art. On the larger scale, it also demonstrates how porous were the cultural and aesthetic membranes that separated one group from the other in this part of the Mediterranean during the later Middle Ages.

The giudecca’s second synagogue was the Scolanova , a simple, unadorned building whose thick limestone walls are pierced by several small windows. Access to the interior is through a door on the south side, reached by mounting a tall staircase. Inside, the synagogue is a single, long, nave-like hall with a niche on the eastern wall where the Torah scrolls were stored. An upper story may once have been a woman’s gallery. The elongated nave of the Scolanova was a form of synagogue construction found in Islamic Spain and northern Italy. As its name suggests, Scolanova was probably built later than the Great Synagogue. Because of its smaller size, it was not intended as the gathering place for the entire community. The building was given back to the community in 2005, thus becoming the eldest active synagogue in Europe.

The adjoining house is also noteworthy. The plan shows a division into various subunits that could support synagogue-related activities, such as the baking of matzot, rooms for small groups of worshippers, study rooms, and so on. It is even possible that the rabbi or patron of the synagogue lived in this house before the synagogue was constructed.

A small synagogue, found in a block of residences nearby, represents a third type – domestic space converted into religious space. The congregation that met here was very small and probably represented a subset of the community. The sources speak of Tedeschi (German) Jews in Trani in the late fifteenth and early sixteenth centuries, perhaps arriving from Venice. They followed a ritual different from that of the local Jews, and so had reason to form a separate prayer meeting. This small synagogue is different from the others, yet enjoys a connection to them via the open piazza.

The fact that the giudecca isn’t walled is significant. Jewish and Christians populations lived side by side, and there was constant exchange between them in shops, in streets and in the port. Thus, the streets of the giudecca flow naturally into the rest of the urban fabric without interruption. Christians came to the Jewish quarter for essential services found only there, and the memory of these activities is preserved in the toponyms: Via Cambio , a small street leading to the port, was the center of operations for Jewish money-changers and bankers.

The fifteenth century was a period of excitement in the intellectual sphere with the arrival of many immigrants from Spain, France, Germany, and other parts of southern Italy. Among the newcomers to Trani was the scholar and translator Tanhum ben Moshe from Beaucaire in Provence, who died in Trani in 1450 and whose tombstone is preserved in the courtyard of the Church of the diocese. Tanhum is said to have translated Hippocrati’s Prognostica, completed in 1406. The presence of such an illustrious figure in Trani suggests that in the fifteenth century Trani attracted out-standing scholars. As late as the sixteenth century, when the community was supposedly in decline, the famous Jewish intellectual Rabbi Yitzhak Abarbanel visited Trani.

Source: A Mediterranean Jewish Quarter and Its Architectural Legacy: The Giudecca of Trani, Italy (1000–1550); Mauro Bertagnin, Ilham Khuri-Makdisi, and Susan Gilson Miller.

It was in San Nicandro that the first mass conversion to Judaism since the end of antiquity took place. All the converts emigrated to Israel shortly after 1948, so unfortunately there is nothing left in San Nicandro recalling this incredible story.

The Jews first arrived in Ancona around 1000 C.E. In the fourteenth century, the city hosted a significant Jewish community, whose activities were organized around the port and commerce with the Orient. In 1541, Pope Paul III encouraged Jews expelled from Naples and, in 1547, even the Marranos from Portugal to settle in Ancona, granting them protection from the Inquisition. A hundred or so Marranos families took advantage of the Pope’s offer. However, the 1555 papal edict Cum Nimis Absurdum was rigorously applied in Ancona.

The Jews were confined within a ghetto, and their commercial activity was limited to trade in second-hand clothing. A papal emissary arrived to crack down on the Marranos. Some managed to flee to Pesaro or Ferrara. Twenty-five Jews were burned at the stake between April and May of 1555. This tragedy had a large and resounding effect on the Jewish world.

At the request of Dona Gracia Nassi, the great Turkish sultan intervened several times. The Jews of the Levant threatened to boycott the port of Ancona and transfer their business to Pesaro. This movement failed mainly due to rabbinical authorities’ fear of provoking the Pope to take even harsher measures. Finally, when the Popes expelled the Jews from papal lands in 1569 and 1593, the Jews were allowed to remain in Ancona.

The community never recovered its previous prosperity, but through its relations with the rest of the Jewish world, it continued to attract rabbis and men of letters. Napoleon’s troops abolished the ghetto and the discriminatory policies against the Jews, but after Napoleon fell from power in 1814, the ghetto was reestablished as the city returned to the Papal States. The ghetto was opened in 1831, but full equality was not obtained until 1861.

Via Astagno forms the ghetto’s principal artery. The Levantine-rite synagogue at 12 Via Astagno was constructed following the initiative of Moses Basola in 1549. It was destroyed in the nineteenth century, but rebuilt in 1876. The large prayer hall on the second floor is still in use. The Baroque aron is decorated with marble columns and faces the tevah, which originally came from Pesaro. Elements of the original interior of the Italian synagogue demolished in 1932 are arranged on the first floor.

The history of the Jews in Senigallia is similar to that of the Jews of Urbino or Pesaro. In the eighteenth century, the Jews numbered 600 of a total population of approximately 5,500 inhabitants. When French troops withdrew, the populace sacked the ghetto, killing thirteen Jews and forcing the others to flee to Ancona. In 1801, Pope Pius VII forced the Jews to return and rebuild their ghetto. As of 1969, only some thirty Jews remained in Senigallia.

The Italian-rite synagogue on Via Commercianti is no longer active. It was constructed at the time the ghetto was created in 1634, replacing the former synagogue found on Via Arsilli outside the Jewish perimeter. The prayer hall is located on the second floor. It still has its furnishings, remade after the ghetto’s sacking, including the gilt aron and the tevah surrounded by a semicircular balustrade standing opposite it. The pews are still in place, as are the placards with the names of the community members when it was still functioning.

The first traces of a Jewish presence in Urbino date to the fourteenth century, when Daniel of Viterbo received authorization to work as a banker and merchant. The Jewish community prospered under the liberal regime of Duke Federigo da Montrefeltro (1444-82), who was interested in Jewish culture and collected Hebrew manuscripts. This situation changed when the duchy came over the authority of the Della Rovere family in 1508 and was subsequently incorporated into the Papal States in 1631. Its ghetto had been established in 1570. In the eighteenth century, the community became considerably poorer. The arrival of Napoleon’s armies brought Jews their freedom, but the troops’ departure was followed in 1798 by anti-Jewish demonstrations. The discrimination disappeared only in 1861 with the incorporation into the kingdom of Italy.

The synagogue is located in the former ghetto. It dates from 1633-34 and was restored in 1848. The prayer hall is located on the second floor of this edifice. The decorated aron kodesh and the tevah face each other and are well preserved. The furnishings and the prayer books are still in evidence.

The famous six-panel series The Legend of the Profanation of the Host painted in 1465-69 by Paolo Uccelo is located at the National Gallery of the Marches (Galleria Nazionale delle Marche). It depicts a Christian woman bringing a communion wafer to a Jewish moneylender as a guarantee on her loan, only to have him throw it into the flames. The blood dripping from the host informs the population about the sacrilege. The woman is condemned to be hanged but pardoned at the last moment, while the Jewish moneylender and his entire family are burned at the stake.

Documents attest to a Jewish presence in Pesaro dating back to 1214. The expulsion of the Jews from the papal states in 1569 led numerous Jewish families to Pesaro, which became the most important center of Jewish life in the Duchy of Urbino. The annexation of the Duchy by the Pope radically changed the Jews’ situation. Three years later, in 1634, 500 Jews were forced to move into a ghetto. After the departure of Napoleon’s troops in 1797, the ghetto and its two synagogues were pillaged.

Pesaro occupies a special place in the history of Jewish printing. In 1507, Gershom Soncino opened his print shop and worked without interruption until 1520, printing, among other things, a complete Bible, twenty treatises on the Talmud, and the Arukh by Nathan ben Yehiel from Rome.

Only the Sephardic synagogue dating from the second half of the sixteenth century remains. It has been absorbed into a large edifice that opens onto the street of the Grand Ghetto, the present-day Via Sarah Levi Nathan. The building houses the schools of the Sephardic community, including a yeshiva and a school of sacred music. One can still see the mikvah, the oven used for baking unleavened bread, and a well. The prayer hall is surrounded by high windows. One the left side of the tevah a a painting of the temple of Jerusalem; on the right is a painting of the encampment of the Jews at the foot of Mount Sinai. The carved, gilt wood aron was moved to the synagogue in Livorno, the tevah is now in Ancona’s synagogue and the grilles that separated the women’s gallery are now in the synagogue of Talpiot in Jerusalem. The vaulted ceiling has been restored.

A rich and influential Jewish community lived in Trieste, a large port city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that became Italian only after the First World War. During the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century, this community had a profound impact of the economic and cultural life of the city. Enclosed in the ghetto in 1696, the Jews enjoyed a de facto emancipation in 1782 through the Toleranzpatent of Emperor Joseph II.

Consequently, the history of Trieste’s Judaism mingles with that of Austria, especially Viennese Judaism, and shares all its splendor. This is still in evidence today by the many palaces of large bourgeois families in the city, such as the Morpurgo de Nilma, the Hierschel de Minerbi, the Treves, the Vivantes, and others. This large commercial port was the empire’s only access to the sea. It was also an intellectual capital, where the Jews, before and after 1918, had important roles as writers (Italo Svevo, Umberto Saba, the publisher Roberto Bazlen, Giorgio Voghera and as painters (Isodoro Grünhut, Gino Parin, Vittorio Bolaffio, Arturo Nathan, Giorgio Settala and Arturo Rietti). The presence of Edoardo Weiss (1889-1970) in the city made it the cradle of Italian psychoanalysis.

During the the first half of the Twentieth century, Trieste was also one of the ports of departure for Jews emigrating to Palestine. The Shoah was deeply felt by the Jews of this city. Nowadays, the Jewish community counts one tenth of what it was before the war.

The Grand Synagogue

Constructed in 1912 by a community that wanted to show its wealth and power, the synagogue of Trieste represents architecturally one of the most significant edifices of emancipated Judaism at the end of the nineteenth century. Spacious, elegant, and free of any kitsch, the synagogue was designed by the architects Ruggero and Arduino Berlam without any regard for expense.

The decorations, in part inspired by those of certain Christian edifices of the Near East (i.e., Syrian), also show – in the mosaics, the starry dome, and the splendid luminosity of the interior – the influences of the styles fashionable in Vienna at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Jewish Trieste

The Jewish cemetery is at 4 via della Pace since 1843. The old one was on the hill of San Giusto (mid 15th century – mid 19th century), behind via del Monte, the steep street in which are now located the Jewish school and the Carlo and Vera Wagner Museum. This was formerly the location of an Ashkenazic oratory where German, Czech, and Polish refugees prayed before emigrating to Palestine between the wars. The building hosted the Jewish Agency for Israel, which helped thousands of people escape from Russian and then Nazi anti-Semitism. In fact, Jews called the port city of Trieste the “Door of Zion”. The oratory is now part of the Museum. Ornaments and gold objects on display here are in some cases quite antique; many come from Bohemia and Germany as well as from Italy.

Narrow streets such as Via del Ponte, near the Piazza della Borsa give an idea of what this former Jewish quarter might have been like a century ago, when it was inhabited by poor Jews and still had four synagogues, whose discreet facades hid richly decorated interiors. The buildings and synagogues of the early Ghetto were totally razed in the 1930s to the great joy of the heads of the Jewish community of Trieste, which had no desire to see the remains of their miserable past. Many of the synagogue’s furnishings are now in Israel.

The Caffè San Marco near the Grand Synagogue, a favorite haunt of Trieste’s intelligentsia, remains one of the most memorable places in the city. Italo Svevo frequented Caffè San Marco, as did a number of artists and writers both Jewish and non-Jewish. The traditions continues today with authors such as Claudio Magris, who dedicated the magnificent pages Microcosmes (Paris: Gallimard, 1998) to the café. The turn-of-century Viennese Succession-style interior is remarkable -as are the coffee and food.

Renowned throughout the city for the quality of its products – not to mention its interior decor – the celebrated pastry shop La Bomboniera was also, until the 1930s, a kosher pasticceria whose Purim cakes made between February and March delighted Trieste’s residents, Jewish and non-Jewish alike.

Morpurgo de Nilma Civic Museum

Installed in the palace he had built in 1875, the Morpurgo de Nilma Civic Museum is named after Carlo Marco Morpurgo, declared a valiant knight of the empire for his achievements. The palace suggests what daily life was like for a large Jewish family of Trieste.

The private apartments are on the third floor and include a magnificent Louis XVI-style music room, a large azure reception hall decorated in the Venetian style, and a pink salon, among others. Other palaces once belonging to great Jewish families such as the Hierschel de Minerbi at 9 Corso Italia, or the Vivante at 4 Piazza Benco are located in the neighboring streets and have been transformed into apartment buildings or offices.

Risiera of San Saba

The Nazis established the only Italian concentration camp with a crematorium, Risiera of San Saba , in the buildings of a former rice-processing factory. It was a camp used for the detention and elimination of Jews, hostages, partisans and political prisoners. For Jewish prisoners, it was mainly a transit site on the way to the extermination camps. Between October 1943 and March 1945, 22 convoys of Jews were deported from Risiera. In total, more than 1000 Jews were deported from Trieste and about 30 were killed in the Risiera.

The site was transformed into a memorial in 1965. Ten years later, it became a Civic museum designed by architect Romano Boico and it has been recently renewed.

In 2025, a powerful gesture by the people of Trieste saved a landmark of local Jewish culture: the Umberto Saba antique bookshop . Opened in 1919 by the Italian poet of the same name, it looked set to close in 2023.

Born in 1883 and related by his mother to the poet Samuel David Luzzatto, he used the money from a family inheritance to open the bookshop, whose walls belonged to the Jewish community of Trieste, while continuing to write. He sold rare and antique books on literature, philosophy, history, religion and boats. In 1924, he hired Carlo Cerne, a young man abandoned by his parents and living in very precarious conditions, whose vocation for this profession he identified.

Together they formed a formidable team, expanding the bookshop. In those dark years, Umberto Saba spoke out and wrote against Mussolini. When the Nazis invaded Trieste in 1943, he had to flee, hidden by friends. Severely scarred by the war, he gradually handed over management to Carlo Cerne, who died in 1957. Cerne hired his son Mario, who took over the bookshop in 1981, after Carlo’s death. Mario ran the bookshop until he fell very ill in 2023, highlighting in particular the work and courage of Umberto Saba.

The building still belonged to the Jewish community of Trieste when the lawyer Paolo Volli, whose offices were located in the same building as the bookshop, organised a fund-raising campaign to save it. This emblematic place motivated the commitment of the literary-minded population of Trieste – after all, James Joyce wrote his masterpiece Ulysses there. It was also a personal story for Volli, Umberto Saba having saved his own grandfather’s book collection by hiding it just before the Nazis invaded.

On 28 January 2025, the Umberto Saba bookshop celebrated its reopening, which included a number of areas, including a museum in tribute to its founder, a reading room and a room hosting literary events. This date marked the one-year anniversary of Mario Cerne’s death. His daughter Ada, who lives in London, took an active part in the project and was officially presented with the keys to the site by the Jewish community at a ceremony. She hired a director to continue this wonderful literary adventure.

Interview with Annalisa Di Fant, curator at the Museum of the Jewish Community of Trieste Carlo e Vera Wagner

Jguideeurope : Can you tell us how the Museum was created?

Annalisa Di Fant : The “Carlo and Vera Wagner” Museum opened in 1993, the brainchild of Mario Stock, at that time president of the Jewish Community, and of Gianna, daughter of Carlo and Vera Wagner, and her husband, Claudio de Polo Saibanti. The set-up was devised by the architect Ennio Cervi, with the scholarly advice of Luisa Crusvar, Silvio Cusin, Ariel Haddad and Livio Vasieri.

The perfect location was found in via del Monte 5-7: a building of particular historical significance to the Community, one which has been declared a site of national interest. Since the end of the eighteenth century to the late nineteenth century, Via del Monte 5-7 had been a Jewish hospital. From the beginning of the twentieth century, it was used to host the thousands of refugees fleeing Tsarist anti-Semitism and, later, Nazism. These refugees left from the port of Trieste to travel to British Palestine or the Americas. The building also housed the Jewish Agency, which assisted Jewish emigrants leaving for Eretz Israel. In recognition of its role during the two World Wars, the city has earned the epithet of Shaar Zion, Gateway to Zion.

In 2014–15, the Jewish Community of Trieste undertook a complete rearrangement of the permanent exhibition. The new museum itinerary and texts were devised by Annalisa Di Fant, under the supervision of Tullia Catalan and with the assistance of the scientific committee, namely Stefano Fattorini, Ariel Haddad, Mauro Tabor, and Livio Vasieri. There were two main objectives: to appreciate the Museum’s wealth of offerings, which in terms of both quality and quantity are among the most important in Italy and which represent a unique testimony of Jewish life in Friuli Venezia Giulia; to make the exhibition as accessible as possible for visitors from Italy and further afield – thanks to English versions of all materials – with the particular aim of engaging school groups.

On 14 September 2014, to mark the European Day of Jewish Culture, the first restored part of the Museum was inaugurated: the section dedicated to culture, which is located on the first floor of Via del Monte 7, where there is also the conference space. The project was managed by Massimiliano Schiozzi and Cristina Vendramin (Comunicarte, Trieste). On 29 March 2015 the restoration was completed, and the ground floor spaces, accessible from Via del Monte 5, were opened, with sections dedicated to the spirituality, traditions and history of the Jewish Community of Trieste, the Holocaust, and the links with Eretz Israel. The project was managed by Giovanni Damiani and Matteo Bartoli (Fresco, Trieste). In 2017, there was a further expansion: the second floor of Via del Monte 7 was transformed into a space for temporary exhibitions. This project was carried out by Giovanni Damiani.

Are there educational projects proposed by the Museum and how is the city of Trieste participating in the sharing of Jewish culture ?

The Museum is particularly dedicated to its links with schools: from teacher training, and the annual organisation of refresher courses, to the warm welcome we extend to school groups of every level.

Since 2017, the Museum, along with the Jewish Community of Trieste, has an ongoing arrangement with the Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici at the Università di Trieste, where Professor Tullia Catalan – the Museum’s academic advisor – works as a lecturer in Jewish History. Thanks to this accord, there are internships of 75 or 150 hours available to those who have taken the exam in Jewish History.

The Museum also has strong and fruitful collaborative links with the Liceo linguistico F. Petrarca and the Istituto Tecnico Statale “G. Deledda – M. Fabiani”, with whom work experience projects have been organised, allowing students from these schools to be actively involved with the Museum several activities.

Can you share a personal anecdote about an emotional encounter with a visitor or researcher during a previous event?

Very recently, the Museum has been visited by an Israeli citizen, a lovely, brilliant gentleman 93 years old! He has very vivid memories of Trieste and in a picture reproduced in one of the Museum’s panels he has recognized his brother, portrayed among others during a Purim at the Jewish School of Trieste, year 1931. They were both born in Trieste to a family that arrived here from Poland after the First World War, being the father called to practice as a shokhet by the Trieste Jewish community. The family quickly entered the local Jewish nucleus and the children attended the community school.

Unfortunately, at the end of the summer of 1938, the whole family, then made up of eight people, was affected by the racial law, which obliged all foreign or stateless Jewish citizens to leave the Kingdom of Italy by March 1939. Thus, after several failed attempts and helped by Misrad who was based in the building where the Museum is located, the Garncarz left with a Lloyd ship on March 29, 1939 for Tangier. And they remained there for four long years, before landing in Haifa in 1943. They had finally found the place to take new roots. But they never forgot Trieste…

Very often, people who fled Trieste because of fascist racial laws come back to see the city and come to visit us. Also, many descendants of the refugees hosted here in the first half of the Twentieth Century come to visit the Museum. These are always very moving encounters and often they enlarge our archives, by donating documents and pictures of those times.

In this little town, as in so many other towns in Venetia, there was a small but flourishing Jewish community.

One can see the street of the former synagogue, whose interior ornaments and decoration were all sent to Israel after the war and installed in the Italian Temple Rehov Hillel in Jerusalem.

On 20 March 1516, Zaccaria Dolfin, an influential Venetian patrician, announced a radical turn in the history of the Jew of the Serenissima: “It is necessary to send all the Jews (zudei) to stay in the geto novo, which is like a stronghold, and to make drawbridges and to surround it with wall so that there will be only one gate that will need to be monitored, and only the boats of the Council of Ten will stay through the night”.

After the council, the senate of the city voted 130 to 44 to enclose the Jews in a specific part of the city. On 29 March, a decree established the first ghetto in an unhealthy, outlying area that was the location of a former copper foundry (geto in Venetian, a plausible source of the word ghetto). Jewish quarter already existed in several cities in Central Europe, but the residential conditions were not as rigorously codified. The “geto” rapidly became famous, its name soon achieving the status of a common noun.

The origin of the word “ghetto”

The noun “ghetto” appears to derive from the name of the islands where the first ghetto was established, having featured a foundry (geto or getto). Although this etymology is generally accepted, it is perhaps too simplistic and leaves some skeptical, for it neglects to explain the shift in pronunciation from the initial sound “zh” of geto to the hard “g” of ghetto. This gutteralization could be due to the pronunciation of Venetian Jews of the period, who were in large part of German origin. Some scholars have suggested other origins for “ghetto”: for example, from the Hebrew word ghet (repudiation or divorce).

Until this time, the Jews of the Serenissimo had had few problems. Some Jews probably lived in Venice as early as the twelfth or thirteenth century, on Spinalonga Island (the reason it has been called Giudecca ever since). However, historians do not agree on this point. The republic needed money, and at the beginning of the fourteenth century it authorized Jewish moneylenders to settle in Venice. Arriving primarily from Germany, the Jews were forbidden to reside permanently in the city and were forced to wear a yellow, later red, beret for easily recognition. Most Jews chose to live in Mestre or in neighboring cities such as Padua.

Beginning 1509, the Jews began to arrive at the Lagoon in greater numbers, fleeing, as did thousands of other refugees, the victories of the papal and Austrian troops allied against Venice. It was in this dramatic context it was decided to create the ghetto nuovo, which held some 700 German and Italian Jews. Then, in 1541, the ghetto vecchio was created for Jews from the Levant and Spain, this last group bing wealthier and engaged in maritime commerce. Among the Jews from Spain were many Marranos.

In 1633, a new zone (ghetto novissimo) was added to the area where Jews were permitted to live in Venice. Their rich Levantine or Spanish families settled. In 1589, some 1,600 Jews lived in the ghettos; by 1630 they numbered 4,870 people, or 3% of the inhabitants of Venice’s city center, but with a population density four times higher than that of the rest of the city. The walls of the ghetto finally fell in 1797 with the arrival of Napoleon Bonaparte’s troops. This ghetto was both the most infamous and sumptuous in Europe; it has maintained almost totally its original structure. Its five synagogues from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries are among the most beautiful in Europe. Scarcely 500 Jews live in the city today. A visit to Jewish Venice requires at least tow days.

As in many other European cities, Venice has experienced violent outbreaks of anti-Semitism following the importation and exploitation of the conflict between Israel and Hamas in the wake of the 7 October pogrom. This included attacks on tourists, including a pregnant woman in August 2025. The following month, a dozen assailants attacked three Jewish tourists.

In an effort to combat the rise in anti-Semitism since 2023 and to continue sharing Italy’s Jewish cultural heritage, numerous events have been organised in recent years as part of European Jewish Culture Days. Among these, in September 2025, an exhibition on the theme ‘The Venice Ghetto on Paper: Exploring Jewish History and Culture through Our Original Books and Manuscripts’ was held at the Venice Centre of Tolerance & ScalaMata Gallery, as well as another on “The Wisdom of the Fathers: Proverbs in the Paintings of Michal Meron” at the Venice Ghetto Centre.

The ghetto

If you cross the small wooden bridge over the Rio del Ghetto Nuovo and then pass beneath a sottoportego (a little arched passageway under a building that is typically Venetian), you can still see the holes in the walls from the beams of the great doors that blocked the passage at night.

Emerging from the sottoportego, you immediately find yourself on the large campo (square) of the Ghetto Nuovo, a trapezoidal space with a few trees ad three wells made of Istrian stone that has remained almost unchanged since the time of the ghetto’s occupation. Only the buildings of the Casa Israelitica di Riposo built on the north side in the nineteenth century have replaced the high facades that surround the rest of the campo. These buildings have eight or nine stories and are still among the tallest in Venice.

A Babel of men and languages

“In the ghetto, one heard the most diverse sounds: not only Hebrew songs or dialects cut off their homelands in the Mediterranean but also the patois colored with Spanish, Turkish, Portuguese, Levantine, or Greek, not to mention the slang of a few Poles or German refugees and the various Italian dialects. A true Babel of men and languages where a few adventurers and shady Marranos stand out.”

Riccardo Calimani, History of Venice’s Ghetto (Paris: Stock, 1988).

The campo was the heart of daily life for Venetian Jews. Here moneylenders set up their tables in front of the houses or under doorways. Although Venice’s Jews excelled in printing and medicine, the rows of strazza (used-cloth) vendors on the square engaged in the other occupation officially permitted to Jews. At number 2911 on the square, one can still see the signboard of the Banco Rosso (which also existed in yellow and green, and so was called depending on the color of the borrower’s note given).

Crossing the Ponte delle Agnudi, one passes from the ghetto nuovo into the ghetto vecchio, which has a calmer atmosphere despite boutiques lining its narrow streets. In the past, every evening both ghettos emptied all of their non-Jewish pedestrians and clients before the doors shut on the enclosed Jews. They were forced to pay guards who, on foot and in boats, enforced their confinement.

The campo nuovo was the only large Venetian campo without a church or palace to define the space. The Scola Tedesca Grande, or Grand German Synagogue, is located at the southeast corner of the square on the second floor of a tall house with large windows. The Scola Canton and the Scola Italiana were located next door. The ghetto nuovo had its gaze turned toward its main synagogues and the land of Israel.

A city within the city

“There was one oven for baking bread and another for baking unleavened bread in each of the ghettos, numerous shops selling fruit and vegetables, meats, wines, cheeses, pâtés, and oil merchants, some frequented by the Germans and others by the Levantines. One found not only tobacco and candle wax shops but also barbers, hatmakers, wet nurses, tailors, booksellers, printers, a morgue for the dead, and an auberge for Jews passing through.”

Donata Calabi, La Città degli Ebrei (The City of Jews), with Ugo Camerino and Ennio Concina (Milan: Marsilio Editions, 1995).

The synagogues

None of the following five synagogues in the campo of the ghetto nuovo or the neighboring streets can be seen without a guided visit.

Constructed in 1528 by Ashkenazic Jews, the Grand German Synagogue (Scola Tedesca Grande) in the ghetto nuovo was the first of the ghetto’s synagogue. The walls of the majestic great hall (46 x 23 feet) appear to be oval, but are actually trapezoidal. They are paneled midway with lovely walnut wood and gilding. Dating from 1666 and covered with gilt, the raised aron (with the Ark of the Torah) is accessed by four pink marble stairs. The golden bimah with its elegant Corinthian columns is from the same period. The aron and bimah face each other from the short walls of the room.

The synagogue was drastically remodeled in the middle of the nineteenth century. In the original layout, the bimah was in the center of the room, as in the synagogues of Germany and Centra Europe, which explains the absence of decorations on the floor in the center of the hall and the octagonal opening in the ceiling. Five large windows inundate the room with light during the day, symbolically representing the five books of the Pentateuch that illuminate the world. Like the other synagogues in the ghetto, this one is on the second floor in order to be closer to heaven and the stars. The Jewish Museum of Venice , opened in 1953, occupies two rooms in the same building as the synagogue. Beautiful silver religious objects, sacred decorations, and interesting manuscripts are on display.

The Canton Synagogue (Scola Canton) is located near the Grand German Synagogue. It is easily recognized from outside by its small gilt dome above a wooden square base erected in 1532 by Jews from the provinces. After crossing a long hallway that served as a “room for the poor” (for those who could not afford to pay for the service) at the top of a narrow staircase and passing through a swinging door, you will enter the lovely rectangular hall (43 ft. x 23 ft.) of the temple. The aron and bimah face each other from the shorter sides of the hall. The aron resembles that of the Grand German Synagogue and dates from the same period (1672), but it is even more splendid.