In the small town of Cherasco, in the province of Cuneo, you can make an appointment to visit a very interesting synagogue on private property. Hardly bigger than a living room, the synagogue features magnificent woodwork and gilding. A plaque at the entrance commemorates the founding of the synagogue in 1797. The baroque tevah in the room’s center is made of polychrome wood. The aron has finely sculpted, gilded swinging doors.

In an effort to resist the rise of anti-Semitism since 2023 and to continue sharing Italy’s Jewish cultural heritage, numerous events have been organised in recent years as part of European Jewish Culture Days. Among these was a guided tour of the synagogue in Cherasco on 14 September 2025.

Saluzzo’s small Jewish quarter maintains its former appearance in the area around Via Deportati Ebrei. In one of the courtyards on this street stands a building containing a synagogue on its third floor. Constructed in the eighteenth century and remodeled in 1832, the prayer hall was designed to accommodate more than 300 persons. Notice the beautiful carved door, as well as the gilt wood aron and the tevah dating from the eighteenth century.

In an effort to resist the rise of anti-Semitism since 2023 and to continue sharing Italy’s Jewish cultural heritage, numerous events have been organised in recent years as part of European Jewish Culture Days. Among these was a guided tour of the synagogue in Saluzzo on 14 September 2025.

The most elegant of the region’s Baroque synagogues is found in the little city of Carmagnola near Turin. The city’s Jewish community was forced to live in a ghetto beginning in 1724.

The temple is on the second floor of an eighteenth-century house opposite the former entrance to the ghetto. Passing through a vestibule decorated with frescoes, you will enter a prayer hall almost square in shape (30 ft. x 33 ft.) with a coffered wooden ceiling and lovely ornamental windows.

In the center stands a magnificent Baroque bimah sculpted of gold, black, red, and green polychrome wood with slender columns supporting a large crown. The richly decorated aron is surrounded by two columns and stucco. The walls are paneled midway in sumptuously carved dark wood. These decorations, apparently older than the synagogue itself, are oversized compared to the dimensions of the room. The woodwork dating from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries is of exceedingly high quality and reminiscent of the furniture in the collections of the royal house of Savoy. “If these are not the same artisans, they belong to the same workshop”, remarked art historian David Cassuto in his study on the Baroque synagogues of Piedmont.

In an effort to resist the rise of anti-Semitism since 2023 and to continue sharing Italy’s Jewish cultural heritage, numerous events have been organised in recent years as part of European Jewish Culture Days. Among these was a guided tour of the synagogue in Carmagnola on 14 September 2025.

Turin is one of the finest examples of the crossroads of Jewish cultures: Ashkenazim from the north, Provençals following the expulsion, Sephardim following the Inquisition, Italians for 2 millennia…

Turin was first the capital of the Duchy de Savoy, then of the Kingdom of Sardinia. The Jewish presence was recorded by the Bishop Maximus of Turin as early as the fourth century. The only trace of Jewish presence to have been recorded then on only appeared a thousand years later. In 1424, French Jews Elias Alamanni and Amedeo Foa settled in Turin.

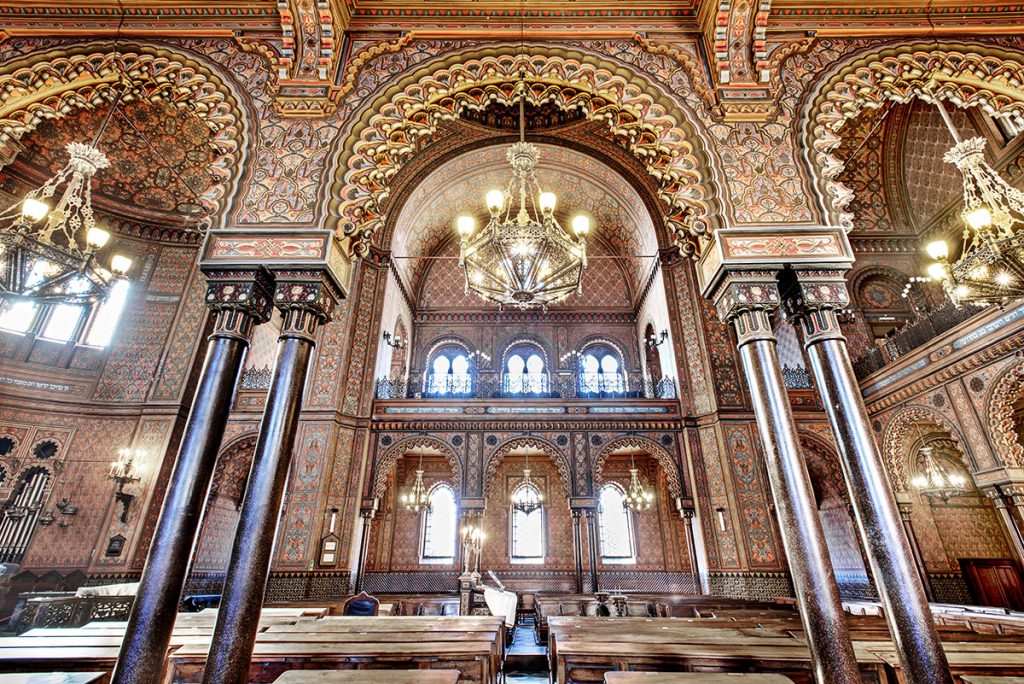

The Grand Synagogue deserves a short visit. Opened 16 February 1884 amid great pomp and ceremony, this majestic neo-Moorish building with its four onion-domed towers attests to the elation of Italy’s Jews after their emancipation. Needless to say, it was in such spirit that the Jewish community decided to call for a competition of projects celebrating the integration of Turin’s Jews. Architect Enrico Petiti did not skimp on the decorations for the building mixing various influences.

Most of which, sadly, were destroyed when the Grand Temple caught fire in 1942 after an Allied bombing. A significant portion of the archives of the Jewish community of Piedmont was also destroyed. The synagogue was restored between 1945 and 1949. Later, a smaller synagogue was built inside those walls. It serves to welcome common events and rituals. It is usually named Tempio Piccolo (“the small temple”).

Some ten minutes away on foot from the synagogue and the community center, behind the animated Via Roma, one can still see traces of the former ghetto .

In 1430, Duke Amedeo VIII decided to create a special status for Jews, imposing many restrictions as well as heavy taxes. The ghetto was thus created in 1679, at the request of the Regent, Duchess Marie Jeanne Baptiste of Savoy. Within a year, the Jews where confined to these walls. A neighborhood which was mostly known its charity institution. The ghetto had two synagogues. After 1724, the number of Jews becoming too big, a new part was added to the ghetto.

The emancipation was a direct consequence of the French Revolution of 1789. Following the annexation of the territory to France in 1798, Jews enjoyed a much greater freedom and weren’t obliged anymore to live in the ghetto. The victory of the Austrians and Russians over the French in 1799 forced the Jews to be submitted again to the former restrictions. After the French reconquered the territory in 1800, Jews recovered their freedom.

Following Napoleon’s defeat in 1814, Victor Emmanuel once again denied the freedoms obtained by the Jews. Nevertheless, step by step, such restrictions disappeared and the emancipation was completed in 1848. Jews gradually left the ghetto. In that year, about 3,200 Jews lived in Turin.

Encouraged by the poet David Levi and the rabbi of Turin Lelio Cantoni, Jews participated in the first War of Independance of Italy. Under Victor Emmanuel II, Jews benefited from a complete emancipation. They gradually integrated the administration, the army and the diplomatic corps. Many Jewish writers and artists participated in the development of the city.

In this emancipation march, it was decided to build a synagogue, before the one known today. A parcel was bought by the Jewish community to build it. Architect Alessandro Antonelli started the construction of the synagogue in 1863. The building was supposed to have the capacity to welcome 1,500 worshippers. But also administrative services, a school and other offices. But the scale of such a project seemed to big for the Jewish community which had to sell the building to the city of Turin in 1878.

The municipality decided to transform the building known today as the Mole Antonelliana into a museum commemorating King Victor Emmanuel II. The construction of the building was finished in 1889 and is 167 meters high. It’s one of the most famous buildings of contemporary Turin.

In 1931, 4,040 Jews lived in Turin. The Racial Laws imposed in 1938 had a profound impact on the assimilated Jews of Turin. In 1942, a bomb destroyed the inside of the synagogue. The following year, the Germans started deporting Jews. Among the 246 who were deported to Auschwitz, only 21 came back to Turin, Primo Levi being one of them. Jews were very involved in the local underground fighting units and found help when the civilians seeked hiding places.

As in many other European cities, Turin has experienced violent outbreaks of anti-Semitism following the importation and exploitation of the conflict between Israel and Hamas in the wake of the pogrom on 7 October. This was particularly evident at the city’s university, where a conference on anti-Semitism held in May 2025 was violently interrupted and the students attending were brutalised.

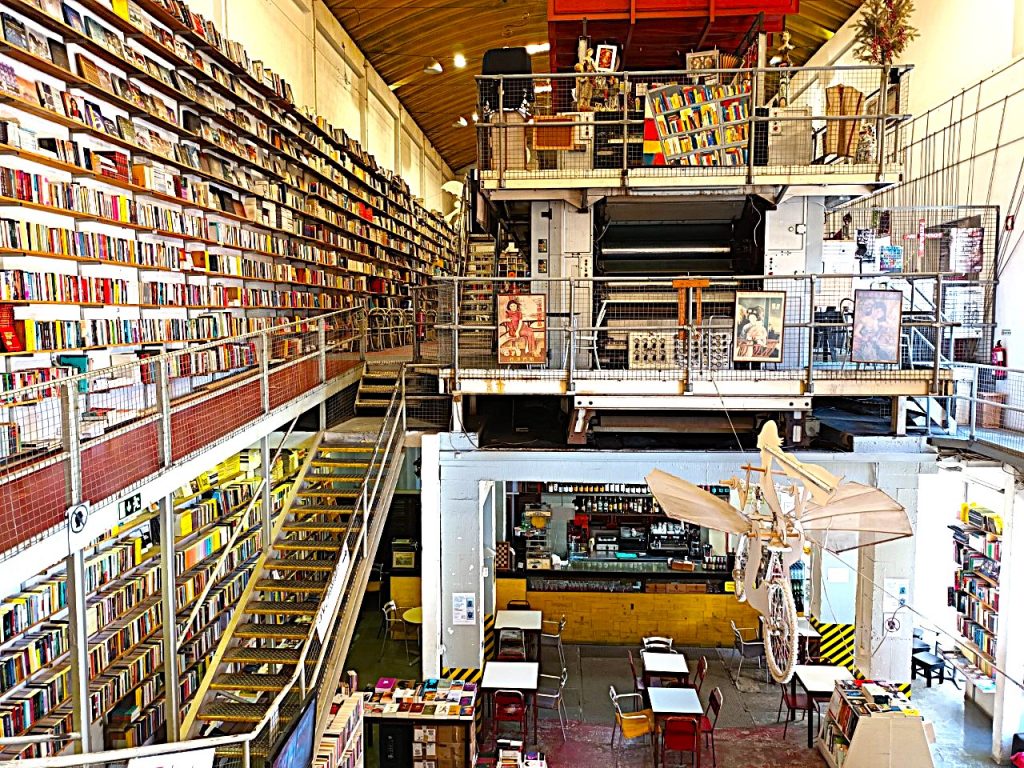

In an effort to combat the rise in anti-Semitism since 2023 and to continue sharing Italy’s Jewish cultural heritage, numerous events have been organised in recent years as part of European Jewish Culture Days. Among these, on 14 September 2025 in Turin, there was a guided tour of the synagogue, the old ghetto and an exhibition on Piedmontese Jewish rituals. A book-themed activity was also organised for children at the Claudiana bookshop, as well as a conference on the theme of ‘The Book from Generation to Generation’ at the Social Centre and, at the same venue, a ‘Tiqqun’ concert by the Davka Project.

In 2026, the Jewish community has fewer than a thousand members. The new rabbi appointed in 2022 has set himself the challenge of encouraging young people to rebuild what was once a thriving community in Piedmont.

The Jewish cemetery changed its location a few times and for different purposes from the 1400s on to the 19th century. In 1867, the Jewish community obtained a section of the Monumental cemetery, where old graves were resettled.

Interview with Baruch Lampronti, representative of the Cultural Heritage Commission of the Jewish Community of Torino and curator of the website visitjewishitaly.it

Jguideeurope: How does the Jewish Community maintain its activities during this crisis?

Baruch Lampronti: Any social activity, like the ritual services, meetings, and the rich schedule of cultural activities are sadly suspended. However, as a member of the Community, I appreciate the efforts that the Board of the Community and the Rabbinate are making. On Purim the Meghillah reading has been broadcasted live on Facebook. The offices’ employees are still active working at home. The teachers of the Jewish school started a daily program for the students via zoom.us. The weekly lessons of the rabbis and the Ulpan courses are now carried out via skype (sometimes they even gather more people than usual). The old age home is strictly isolated: it lets in only the staff but they set up a specific skype account to keep the guests in touch with their relatives. The Community is also arranging a small task force of volunteers available to assist people with needs, with daily calls, shopping deliveries (in particular now that Pesach is approaching), and maybe more.

The UCEI – Union of Jewish Communities in Italy is putting as well great effort to make people feel its presence through different ways which include practical services, with a call center of psychologists and social workers, and with a rich schedule of lectures, talks and other shows live broadcasted every day on its Facebook channel.

So, how does the Community maintain its activity? In this moment, I personally think that keeping a sense of family and sympathy despite the distance is one of the most important elements of the Community life to be maintained. Of course, this goes together with the great work that doctors and paramedics are carrying out with dedication and self-sacrifice.

What inspired the unique design of Torino’s synagogue?

The Moorish style was required in the call for the design competition, and it must be traced back to the trend in contemporary synagogue architecture in Europe. This, in turn, was definitely influenced by the taste for the exoticism spreading from the second half of the XIX century, that we can recognize in many other non-Jewish buildings of the eclectic trend. With regard to the design of the synagogues, the choice of inserting oriental references was nevertheless supported by more meaningful arguments. If you find that interesting, I paste below a few lines from a short paper I wrote about the Torino synagogue:

“While the magnitude of the volumes of the Emancipation synagogues and their autonomy from the surrounding buildings can be traced back to a desire of equality and assimilation to the churches’ model, the stylistic language instead expresses a search for individuality from the worship places of the other denominations. Thus, a sort of debate develops around the most appropriate style to express the Jewish identity of the place. “A truly Jewish style – to my knowledge – does not exist” stated in a report the Jewish architect Marco Treves from Vercelli, engaged in the renovation of the synagogue of Pisa (1865) and in the design of the new temples of Vercelli (1878) and Florence (1882). He observed that even the Temple of Jerusalem, according to archaeological evidences, probably did not express a style purely representative of the Jewish people but it followed the main artistic influences of the region. Subsequently, the various conditions, often oppressive, experienced by the Jews in diaspora had precluded the definition of national stylistic traits or of a specific synagogal architecture.

In the composition of the Israelite temples, in Italy as well as in Europe, the designers will often orient themselves towards oriental-style repertoires, that they considered representative of the geographical origin of the Jewish people. References to Assyrian-Babylonian, Egyptian and Byzantine styles emerge; among the most widespread references, theorized by Treves too, we find those from the Moorish style, which hint particularly to the architecture of medieval Spain. The Jews spent there an epoch of great freedom and cultural fervor, and erected their synagogues in line with the local taste of the period (among the best known examples, Santa Maria la Blanca in Toledo, built in 1180 and transformed into a church at the end of the 14th century). In many nineteenth-century’s temples can be found horseshoe arches, onion domes, battlements and turrets of Islamic inspiration, and, among the internal ornament, rich stuccoes with geometric motif and arabesque paintings. The Turin synagogue is part of this trend as well. Designed by Enrico Petiti after the unsuccessful experience that would have given rise to the Mole Antonelliana, it was hit by the bombings of November 1942 and it lost any trace of the original internal decoration.

The taste for exoticism and, more generally, the recomposition of different traditions – being them distant or local, contemporary or ancient – which aim at revealing the identity of the building, make the synagogue of Emancipation an important example of the historicist architecture and the eclecticism.” You can find the entire article in Italian on this page

Are there traces of the former ghetto which can still be seen today?

The ghetto of Torino was made of just one and a half blocks, and they still exist. The entire block, which is the older one (used from 1679-1680) maintains the original volumes, however the interior and the façades have been deeply transformed a few years after the emancipation (1848). The other half block, added sometime after 1724, has been also renovated in the interior, but the facades reveal quite clearly the former identity of the building. This block is at least one floor taller than the surrounding buildings. In order to enlarge the residential surface so as to host more Jewish families, the floor with the greatest height was divided in two lower floors, and as a consequence its Windows are more numerous and very close to one another. The building is now clean and well painted but there have not been relevant structural changes nor ornamental additions.

What other places linked to Jewish culture in the city trigger the interest of visits?

In addition to the synagogues and the former ghetto, the most representative sites of the Jewish history of Torino are the Mole Antonelliana and the Jewish sections in the Monumental Cemetery.

Piemonte was also studded with a network of smaller Jewish communities, which shared in many respects a common history. Now these communities are almost entirely extinct (at least in place) but they left a multitude of synagogues, former ghettos and cemeteries. Most of them belong to the Community of Torino that takes care of them and that is the point of reference for visits. More specifically, our jurisdiction includes the synagogues and the cemeteries of Alessandria, Asti, Carmagnola, Cherasco, Cuneo, Mondovi, Saluzzo and in part Ivrea, and the cemeteries of Acqui Terme, Chieri, Fossano and Nizza Monferrato (towns whose synagogues have been dismantled in the past).

Other relevant Jewish sights in the region are:

– the synagogues and the cemeteries of Vercelli and Biella, together with the cemetery of Trino Vercellese, which belong to the Jewish community of Vercelli & Biella

– the synagogue and the cemeteries of Casale Monferrato, with the cemetery of Moncalvo, which belong to the Jewish community of Casale Monferrato.

Information and contacts for visits can be obtained on two major sites : the one created by the Jewish Community of Torino: https://torinoebraica.it/turismo/?lang=en and http://www.visitjewishitaly.it/en/ , an informative tool developed by the Foundation for Jewish Cultural Heritage in Italy, which provides descriptions and pictures of many sites of the Jewish Italy, among them the ones above mentioned. We are currently working on some updates so I apologize for any malfunction or missing information.

Modena has the great merit of being known for quite different monuments. Architectural and religious monuments, as in many Italian cities, and gastronomic masterpieces such as its famous vinegar. But there are also contemporary monuments that you can take the time to admire when they’re not speeding past you, the Ferraris and other Lamborghinis and Maseratis built in the region…

History of the Jews of Modena

The Jewish presence in Modena probably dates back to the 15th century, when they found themselves under the protection of the Dukes of the East. In 1443, they were obliged to wear a distinctive sign. Eight years later, a papal bull authorised them to settle freely.

Following the Spanish Inquisition in 1492, Sephardic Jews migrated to Modena, as well as other Italian cities. A ghetto was established in Modena in 1638. Numerous synagogues and oratories were built at this time. The city was an important centre of Jewish studies, thanks to the influence of numerous scholars.

An ancient document proves the existence of a Jewish cemetery . It was located near the present-day Via della Fosse. It was used until the 17th century. A Jewish plot was set up in the San Cataldo cemetery.

Like in the other Italian territories conquered by Napoleon, the Modena ghetto was abolished in 1796, but reinstated in 1815. It was not until the territories were annexed to the Kingdom of Italy that the Jews became full-fledged Italian citizens in 1860, enjoying the same rights as their compatriots.

As a symbol of this integration, a magnificent synagogue was built in 1869. At the same time, part of the ghetto was razed as part of an urban renewal program. Although the community numbered almost a thousand in the mid-19th century, this figure gradually declined, due in particular to the many departures to Milan.

Just under 500 Jews lived in Modena on the eve of the Second World War. Of these, 70 were deported during the Holocaust. Many Jews took part in the Resistance. Angelo Donati, who fought in the First World War and later became a diplomat, organised the escape of thousands of Jews, while the president of the community, Gino Friedman, managed the protection of many young refugees. Although relatively small, the Jewish community remains very active culturally.

Visit Modena

Getting off at Modena station, you take the Sgarzeria, where the old tobacco factory is located. Continue along Via Francesco Rismondo, with its yellow, orange, clay, pink and red buildings.

Then Via Emilia Centro and you turn right onto Corso Duomo, a pretty square with many cable cars intertwined like irremovable metal clouds, populated by terraces, arches, kiosks and passers-by twirling around. And there’s a surprising little sculpture of a football player in homage to Pannini, the famous inventor of sticker books.

A little further on, past the square with its merry-go-round, you finally arrive at the Palazzo dei Musei, which houses the state archives, a library and the city’s museums, a complex rather like the old building housing this type of venue in Parma.

Take the narrow streets towards the cathedral and you’ll come across the Sala Truffaut, a film club named in tribute to the French director Via degli Adelardi. A pretty square then awaits you at the corner of Via dei Servi and Francesco Selmi.

A hundred yards further up, in Via Luigi Albinelli, you’ll find the town’s historic covered market with its stalls and long tables. Please note that opening times are limited out of season.

Walk another hundred yards, past the pretty Piazza XX Settembre, to arrive in Piazza Grande. The city centre is home to the cathedral, which faces the Palazzo Comunale. The juxtaposition of temporal and spiritual powers is common in this region of Emilia Romagna. Modena’s cathedral is very different from its neighbour in Parma, which is fairly sober, with its red bricks and murals in the background.

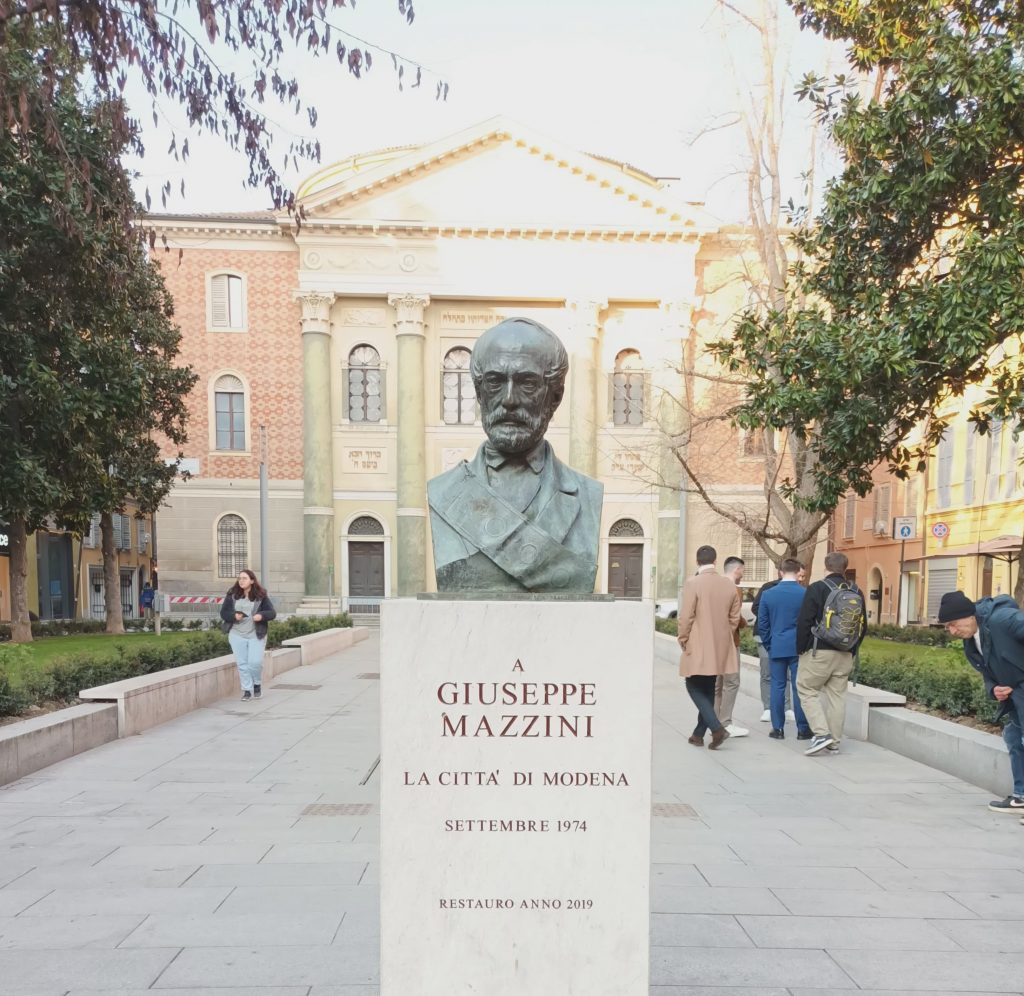

A little higher up, you come to Piazza Mazzini, named in honour of Giuseppe Mazzini, the Italian revolutionary and patriot. A statue pays tribute to him.

Also on display at the entrance to the square is a map of the areas of Modena that were bombed during the Second World War.

At the end of the square is a beautiful orientalist synagogue, built between 1869 and 1873 to a design by Ludovico Maglietta. It has a double façade, one overlooking Piazza Mazzini and the other Via Coltellini. Inside, the circular prayer room is surrounded by a Corinthian colonnade that supports the women’s gallery.

The façade of the synagogue bears the Hebrew words “Baroukh haba beshem Hasehm” and “Ptekhou li Shaaré tsedek”, meaning “Welcome in the name of God” and “May the gates of justice be open to me” respectively. A message of openness and the quest for tikun olam, the repair of the world.

The street to the right of the synagogue is via Biasa, on and around which the ghetto was located.

You then come to the impressive Palazzo Ducale building, where Italian army officers are trained, which overlooks Piazza Roma.

Turning left into Piazza San Domenico, you can see the statue of a woman on the Monument to Liberty.

To the right of the square, a statue of the famous opera singer Luciano Pavarotti stands on Via Carlo Goldoni, inviting you to enter the municipal theatre that bears his name and is located behind him. Next door is the Museo Pannini, less generous and surprising in its presentation than the stickers we used to find in his parcels as children.

In the same Palazzo Santa Margherita complex, there is a library frequented by students who sit in the courtyard, where since 2023 there has been an exhibition showing numerous photos of the streets of Modena in 1973 and the same places photographed in 2023. The perceptible changes include the replacement of bicycles by cars, the addition of security gates and, above all, the many renovated buildings. In the city that is home to the Ferrari museum, this is nothing more than a tribute.

A little further up, the Italian Officers’ Riding School provides a transition before you reach the pretty little Parco Ducalo Estenze, which leads you to the station. And if you have the time, and have completed your visit at 200 miles an hour, you deserve a visit to the Enzo Ferrari Museum, located behind the park to the right of the station.

Ferrara, a sublime city with a medieval centre listed as a World Heritage Site, does not appear to be a vast, museum-like enclosure encircled by a city. On the contrary, its historic centre is delicately interlaced with long, beautiful streets leading to monuments and a gentle way of life that is far from fleeting and to which its inhabitants cling, as did, despite everything, the characters in Vittorio de Sica’s film The Garden of the Finzi Contini (1970)…

History of the Jews of Ferrara

The Jewish presence in Ferrara dates back to at least the 13th century, when the city welcomed Jews from other Italian and European cities. This presence was formalised in 1287 by an ordinance. As long as it remained the capital of the Dukes of Este until 1598, Ferrara was one of the great centres of Italian and European Judaism, with over 2,000 Jews for 30,000 inhabitants during its golden age, between the 15th and 16th centuries. This was also a period in history when many artists and writers also found refuge here.

A synagogue was built in 1481. A synod of the rabbis of Italy was held in Ferrara in 1534. Ashkenazim from Germany and Sephardim welcomed after their expulsion from Spain lived side by side under the protection of the local authorities.

The corso della Giovecca, the main street linking medieval and Renaissance Ferrara, bears witness to this happy past. Prestigious rabbis and doctors lived in the city, which, like Bologna, was a centre of Jewish printing. Abraham Usque published the famous Ferrara Bible here in 1555.

Things came to a head in 1597 when Duke Alfonso d’Este died without a male heir. The Papacy took control of the city, which had been abandoned by the d’Este court, who, like many Jews, left for Modena. The ghetto was established in 1627.

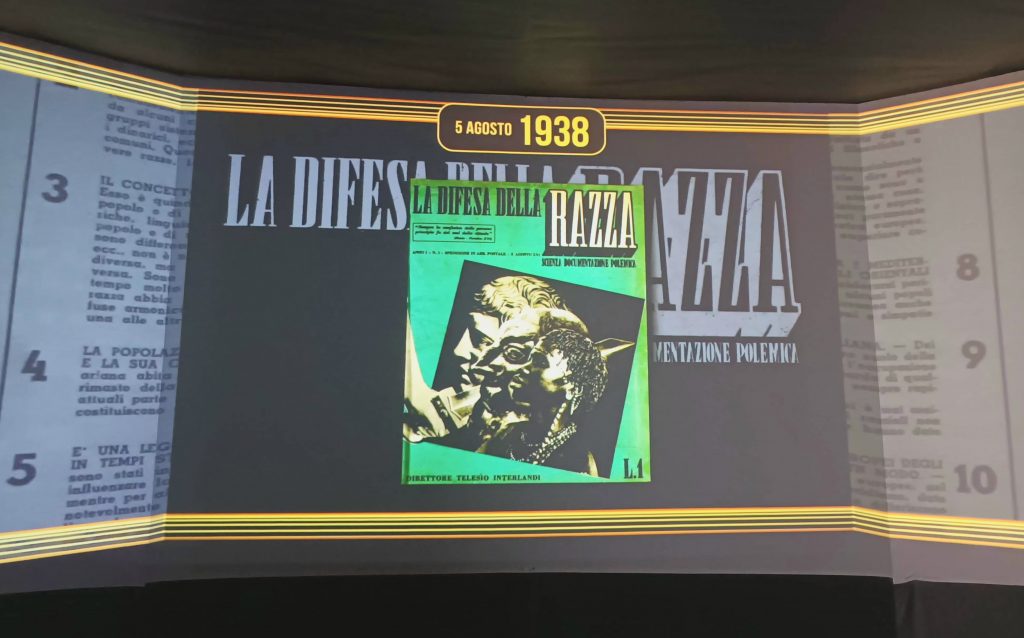

Despite the difficulties, and even after emancipation (1859), the Jews remained fairly numerous in the city, until the racial laws imposed by Mussolini in 1938. This tragedy was admirably recounted by the writer Giorgio Bassani, who devoted most of his books to Jewish Ferrara. Nearly 200 Jews were arrested and deported to the camps from 1943 onwards. The fascists destroyed a synagogue and other community property. Following the Liberation, a small Jewish community was reborn and, since 2017, has been home to the National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah (MEIS) .

Visiting Ferrara

The MEIS can be reached from the station by taking Via Pavia. On the way, you’ll see the city’s football stadium on the left and the Aqueduct on the right, where there is a statue of a man pouring water over children, a city caring for its new generations. This is also the site of the family assistance centre.

The permanent exhibition is housed in the MEIS interior building, separated by a park, and the temporary exhibition in the building located at the front of the complex. The permanent exhibition is devoted to Italian Judaism from Antiquity to the Renaissance.

Antiques, panels, reproductions and videos by specialists harmoniously accompany this itinerary. It’s a collection that’s much appreciated by young people in particular. When we revisited the museum in 2024, we witnessed a class of schoolchildren from Ferrara enthusiastically following this itinerary.

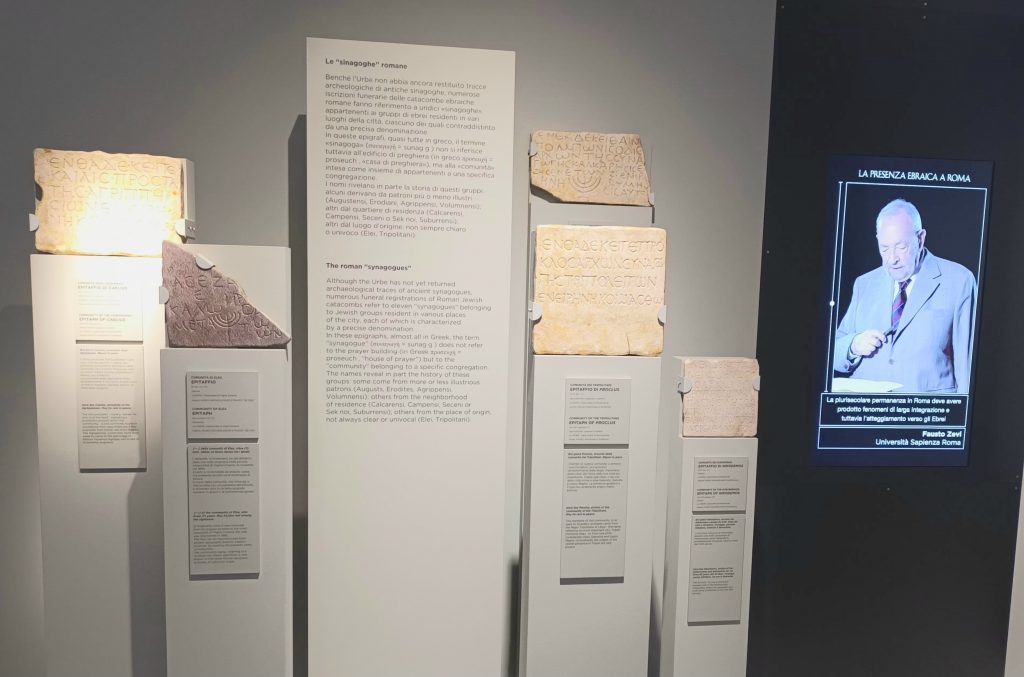

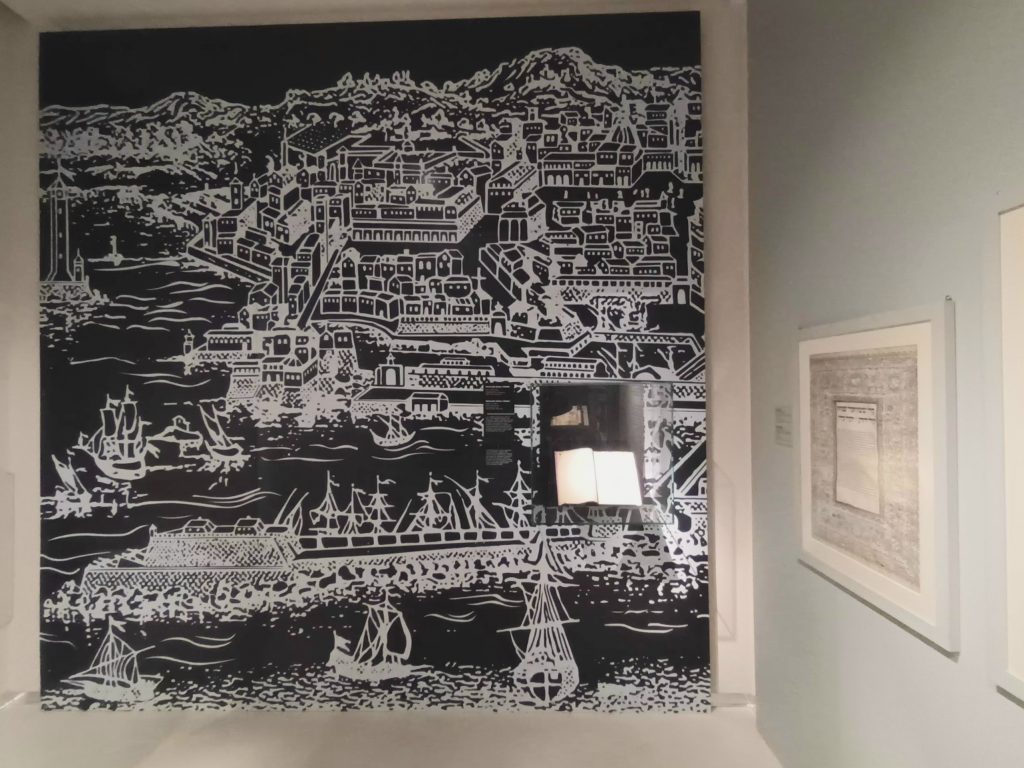

Like the Jewish Museum in Bologna, the tour begins with a general presentation of Judaism. First, we discover the oldest traces, then we come to the Revolt of 70 in Israel against the Romans, with the reproduction of the famous engraving of the Arch of Titus. You will also discover the ancient synagogue of Ostia.

The signs indicate that the Jews have been Roman citizens since 212, thanks to the Edict of Caracalla, like all the other minorities. Seneca and other intellectuals gave them a somewhat lukewarm reception, not understanding the “usefulness” of Jewish customs, particularly the day of rest, which they considered to be idle.

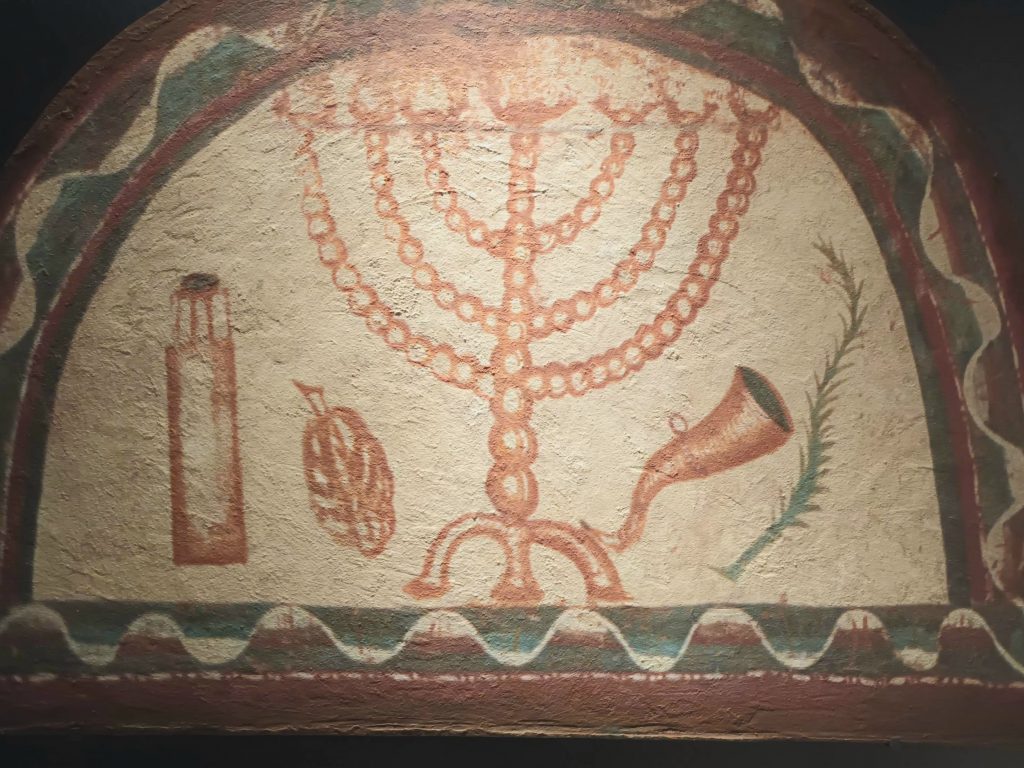

Next, we see the ancient catacombs with a drawing of a menorah dating from the 2nd or 3rd century and found by accident in 1859 in via Antiqua. Then, a mosaic from southern Italy. From 313 onwards, the situation worsened for the Jews, particularly when Constantine promulgated very harsh laws banning Jewish-non-Jewish couples. Nevertheless, the practice of Judaism remained free.

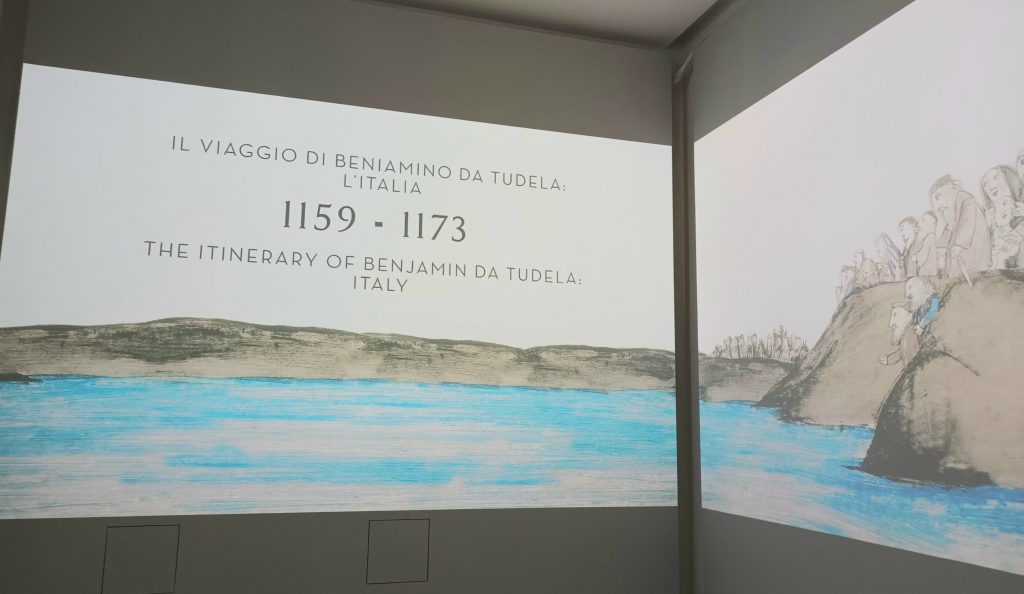

A film is then projected onto the walls of a room, recounting the famous 12th century voyage of Benjamin of Tudela aiming to discover the variety of European Judaism. With images on three walls simultaneously.

Following the decline of Rome and the Inquisition, we discover the migration of Italian Jews to other regions, particularly to the north. From the 14th to the 16th century, the attitude of political and religious leaders varied. During this period, ghettos were established, starting with Venice in 1516. The museum highlights the exceptions of Pisa and Livorno, which never built ghettos to confine Jews. Duke Ferdinand de Medici invited the Jews to settle and work there freely. They were able to enjoy freedom of worship, protected from the Inquisition.

The permanent exhibition therefore stops at this period. Museum officials told us that the MEIS was preparing the continuation of the permanent exhibition, from the Renaissance to the present day.

Leaving the museum, turn right into Via Piangipane, then left into Via Boccacanale di Santo Stefano and second right into the beautiful Via delle Volte where you’ll admire, as its name suggests, a multitude of vaulted elevated passages.

At the end of Via delle Volte, turn left onto Via delle Scienze, where you will find the Biblioteca Ariostea . This library holds many manuscripts, books and engravings on Jewish Ferrara.

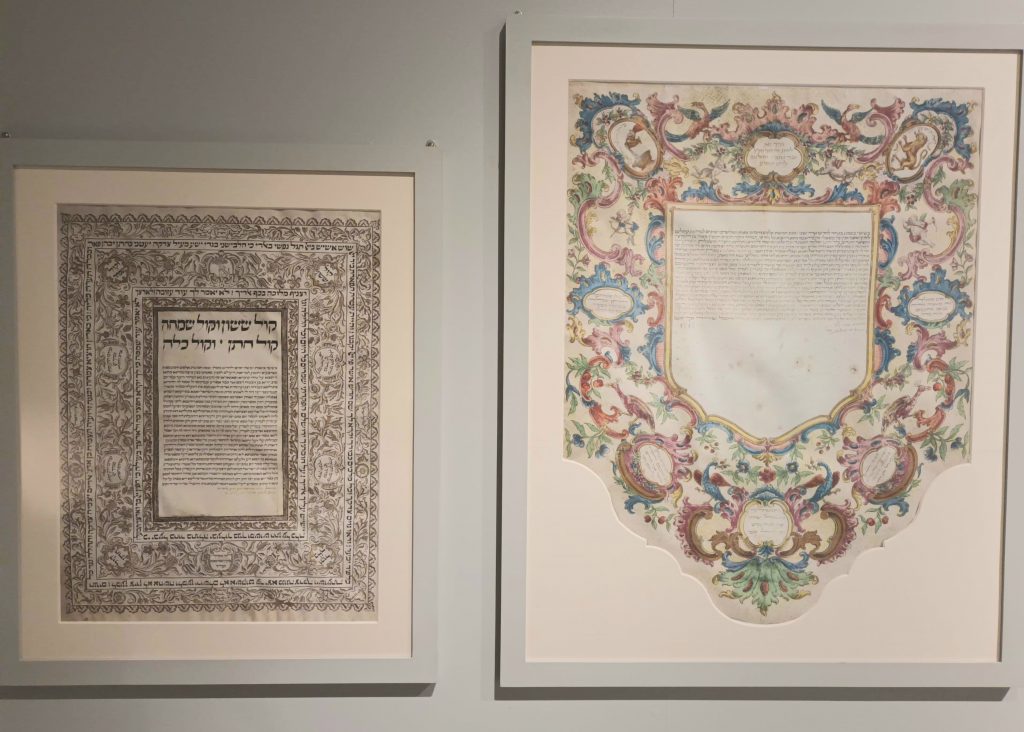

Continuing north along this street, take the first turning on the left into Via Giuseppe Mazzini. At number 95, you’ll see Ferrara’s old synagogue . The magnificent scola tedesca is currently only used for major ceremonies. The prayer room is lit by five large windows overlooking the courtyard. The opposite wall is decorated with beautiful medallions and stucco depicting allegorical scenes from Leviticus.

At the top of another staircase and a long gallery is the elegant room of the scola italiana, which is no longer used for worship. On the far wall are three precious aronot in lacquered wood with elaborate carvings. The one in the centre, all gold and ivory, belonged to the scola italiana, while the other two, blue-green, each with two magnificent twisted columns, come from the old scola spagnola in via Vittoria. Furniture from the rabbinical academy has been placed in the vestibule.

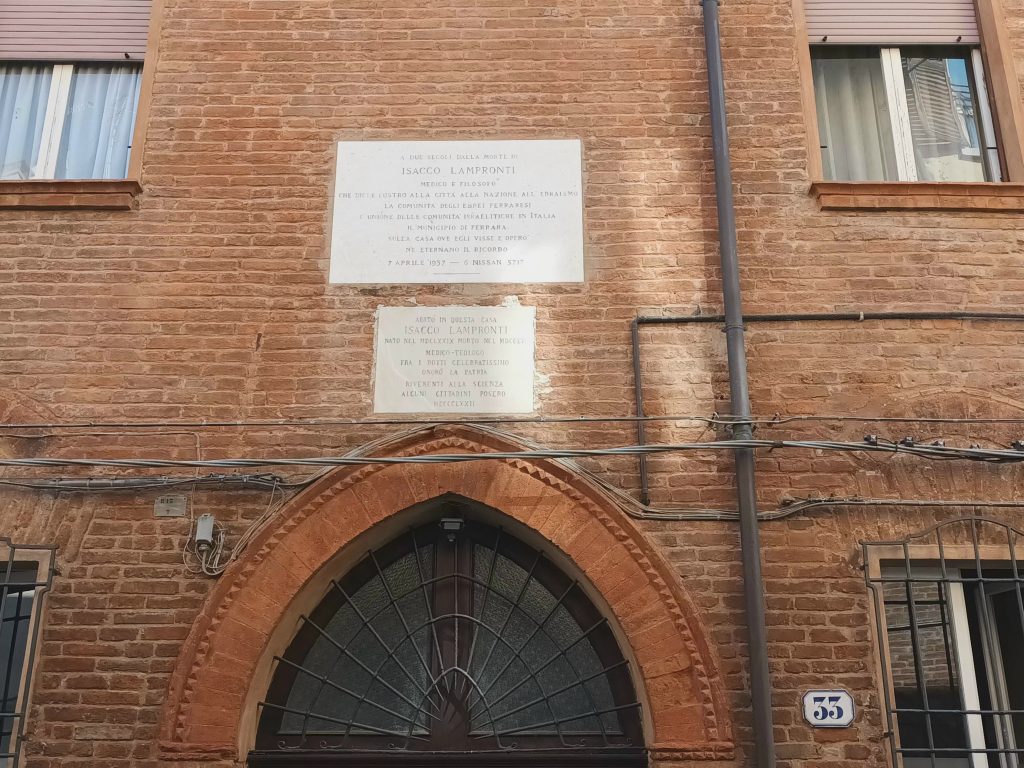

A little further along Via Mazzini, turn left into Via Vignatagliata, one of the main streets of the former Jewish ghetto . At number 33 is the house of Isacco Lampronti, a doctor, philosopher and important representative of the community.

The Jewish school was located at number 81 on the same street, with its many pretty orange houses.

A small square bears the name of Lampronti, between Via Vittaglia and Via della Vittoria, one of the other main streets in the Ferrara ghetto.

Leaving the ghetto, follow Via Ragno to Corso Porta Reno, which leads to the lovely Piazza Trento-Trieste, dominated by Ferrara Cathedral and the Torre della Vittoria. Between them lies the handsome Palazzo Municipale, the whole forming a spiritual and temporal city centre ensemble, as in many Italian cities in the region.

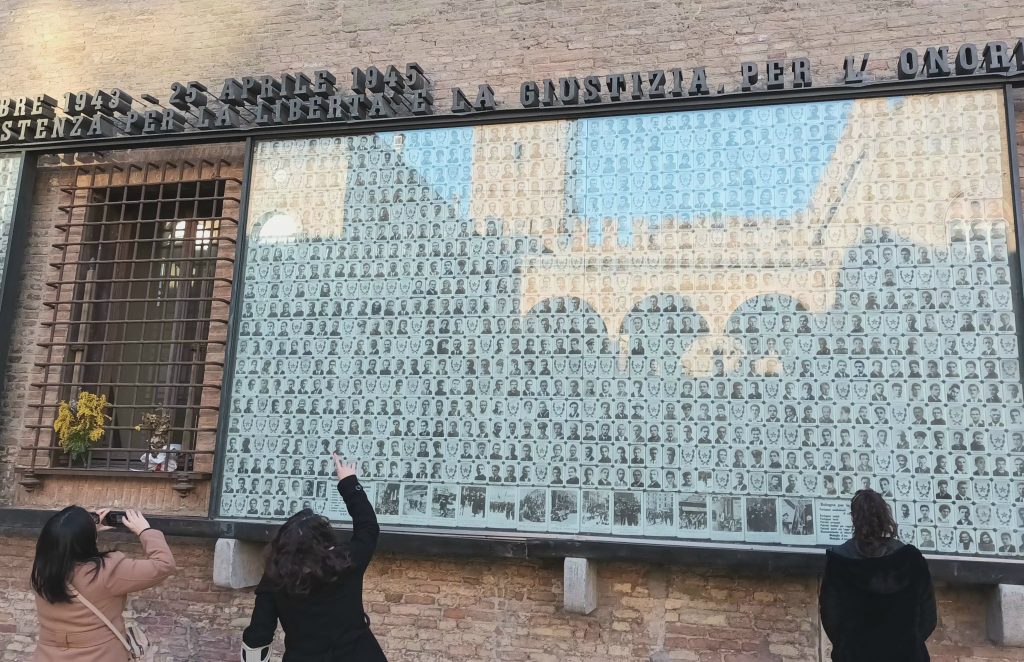

Numerous tributes in the form of plaques are placed on the municipal buildings and palaces surrounding the cathedral, in memory of people from different eras who fought for freedom.

A little further up Corso Porta Reno, you come to the castle surrounded by pools of water, making you wonder which one is protecting the other.

If you go around the castle to the left, you will come to Corso Ercole d’Este. This leads to the Museum of the Resistance, the location of the Finzi-Contini film set and the famous Palazzo dei Diamanti, so named because of its unique architecture. It hosts some very fine exhibitions.

A little further on, turn left onto Via Arianuova towards the small Levantine Jewish cemetery , a trace of Ferrara’s former Sephardic presence. It is located on the small Via Gianfranco Rossi between a few houses and a car park, next to a school where a plaque in honour of a teacher deported to Buchenwald can be seen on the outside wall. The cemetery is currently closed to the public.

To get to the main Jewish cemetery , you can walk through the pretty Massari Park, which may remind you of the great actress Lea Massari, although this is a much older tribute. While there is a café called Central Park, it is unlikely that this park will be twinned with the one in Manhattan.

But it’s a pleasant place to stroll, to salute the statues of Verdi and Dante and to admire the 2015 fresco dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Ferrara.

Leaving the park, take Corso Porta Mare. Then, in Via delle Vigne, you come to the Cimetero Ebraico, in use since 1620, in front of its large entrance gate with Hebrew inscriptions. The cemetery is mainly open to the public in the morning.

After this long day, you can enjoy the beautiful Piazza Ludovico Ariosto, choosing to sit on the stone benches that surround it or at the café under the arcades that will remind you of Bologna.

Interview

MEIS was a challenge from the moment it was built: to transform a place of confinement into an open and inclusive space. Meet Rachel Silvera, Director of Communications at MEIS, who tells us about this important place in Italian Jewish cultural heritage and the many projects it organizes.

Jguideeurope : Can you present us some of the objects shown at the permanent exhibition dedicated to Jewish Italian history?

Rachel Silvera : In our permanent exhibition “Jews, an Italian Story” we display objects loaned by other Italian museums, reconstructions, and multimedia installations. For example, our visitors can admire the relief from the Arch of Titus showing the spoils of the Temple, a plaster reproduction made in 1930. The relief depicts the triumphal procession of Titus in Rome after the military campaign in Judaea, parading the spoils looted from the Temple of Jerusalem. You can also find the reconstructions of Jewish Catacombs, in Rome (like Villa Torlonia and Vigna Randanini) and in the South of Italy (Venosa).

How do you perceive the evolution of interest in Shoah studies in Italy?

It is a fundamental way: 1) to know the history and strengthen awareness 2) to offer useful tools to the students and transmit values to the next generation 3) to fight Holocaust denial and distortion.

Which educational projects focusing on the Shoah are being conducted by the Museum?

During the pandemic we have organized two important online events for school students devoted to the Shoah and the future of the remembrance. We have reached more than 12.000 students. Every year we also offer an online course addressed to teachers focused on Shoah history and the relationship with new medias. We are working also on a project financed by the Ministry of Public Education along with a high school from Ferrara (Liceo Roiti) and the Institut of Contemporary History of Ferrara: the students are working with us to create an exhibition focused on the Racial Laws and the persecution.

Can you tell us about a moving encounter at the Museum with either a visitor or exhibition participants?

The Museo Nazionale dell’Ebraismo Italiano e della Shoah (National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah) is in Ferrara, in the former prisons of via Piangipane. During the war, its walls imprisoned antifascist opponents and Jews, including the writer Giorgio Bassani, Matilde Bassani and Corrado Israel De Benedetti. The challenge was to transform a place of confinement into an open, inclusive space.

During the last International Holocaust Remembrance Day, we unveiled a commemorative plaque that remember the story of this place. The special guest was Patrizio Bianchi, the Italian Minister of Education. It was a really touching moment.

Bologna is famous for having been one of Europe’s leading cities in the Middle Ages. Thanks to its large population living within its walls, the wealth of local agriculture, the development of trade with the other cities of Emilia-Romagna, but also and perhaps above all to the dynamism provided by its university, the oldest in Europe.

History of the Jews of Bologna

The first traces of a Jewish presence in Bologna date back to 1353, when a document mentions a certain Gaio Finzi, “judeus de Roma”. Jews from the surrounding towns of Fabriano, Pesaro, Orvieto and Rimini also settled here in the second half of the 14th century.

The Italian rabbis met in Bologna in 1416 to agree on a petition submitted to Pope Martin V. In 1468, a professor of Hebrew was recruited by the University of Bologna. Between 1477 and 1482, a number of Jewish publishing houses were established, remaining active until the middle of the 16th century.

Following the Spanish Inquisition in 1492, Sephardic Jews settled in Bologna, including Rabbi Jacob Mantinus. Ovadyah Sforno, a doctor and rabbi, founded a renowned Talmudic school in 1527. In 1553, following a counter-reformation campaign, Talmud and other Jewish books were publicly burnt.

Two years later, Pope Paul IV forced the Jews to live in ghettos in all the cities of the Papal States. The one in Bologna was created in 1556 and closed by two gates. In 1569, the Jews of Bologna were expelled from the city. Pope Sixtus V authorised their resettlement in 1586. But they were expelled again seven years later.

It was not until 1796, with Napoleon’s conquest, that the Jews of Bologna were allowed to return and, above all, to worship freely, as was the case in France following the emancipation of the 1789 Revolution.

As a sign of its official recognition, the Jewish community was given access to an oratory in 1829. Following the loss of power by the Church and the proclamation of the Roman Republic, all Italian Jews were officially declared free in 1860. Nine years later, a plot of land in Bologna’s municipal cemetery was granted to them. The Bologna synagogue, built by the architect Guido Lisi, was inaugurated in 1877.

Following the promulgation of the “racial laws” in 1938 by Mussolini’s regime, Jewish teachers and students were excluded from schools and universities. The deportations of Bologna’s Jews began in November 1943. This was the case for 85 of them, including Rabbi Alberto Orvieto. Following the Holocaust, the Jewish community was rebuilt and by 2026 had grown to almost 300 members.

As in many European cities, Naples has been affected by the importation and exploitation of the conflict between Hamas and Israel following the pogrom of 7 October. Violent demonstrations took place in Bologna, including one allegedly against the police. The ‘protesters’ found a ‘pretext’ for vandalising the synagogue in 2025.

Tour of Bologna

We invite you to follow an itinerary through this sumptuous city, with its red buildings and temper by day and subtle yellow lighting at night.

The train takes 7 minutes from the airport to the station. As soon as you get off, you notice the arcades.

Arcades from different eras, in different styles, everywhere, overhanging the streets. A policy of building expansion put in place in response to the problems of overcrowding in this city, which was already one of the five largest in Europe in the Middle Ages. A desire to build forwards rather than upwards. Perhaps also a way of protecting and accompanying passers-by.

To the right of the station, you’ll find working-class neighbourhoods, as well as MAMBO, the Museum of Modern Art, a multi-disciplinary cultural complex that houses a film school with a lovely graffiti tribute to Agnès Varda at the entrance. Also in the area, the park named in tribute to 9/11 and the monument in Place Lamé, with its sculptures in memory of the partisans.

Take the main boulevard Via Giovanni Amendola, which runs from the station to Piazza dei Martiri 1943-1945 and then becomes Via Guglielmo Marconi, which leads directly to the Bologna synagogue by turning left into Porta Nova.

The contemporary synagogue is on Via Finzi, at the western entrance to the old quarter. A small oratory was founded by Angelo Carpi in his house in 1829. In 1868, the growing community rented a room in a building on Via Gombruti. Between 1874 and 1877, a larger synagogue was built in the same building. The synagogue was destroyed in an air raid in 1943 and rebuilt in 1953.

The main hall is now used only for major festivals. In 2017, a small synagogue was built underneath the building. During the works, a Roman mosaic and other magnificent ancient works were discovered. In order to preserve and allow visitors to see them, the floor of the synagogue was constructed in the form of a grid. The community may be small, but it remains fairly dynamic and enthusiastically welcomes visitors Shabbath. “Naturally”, for security reasons, visitors must apply by e-mail. The synagogue was the victim of an anti-Semitic attack in January 2025, causing damage.

We then take the Porta Nova, which leads to the Via IV Novembre, to bringing us closer to the heart of the old town. Continuing in a straight line, you arrive at the famous Piazza Maggiore and Piazza del Nettuno (with its statue of the god of the seas), home to the sumptuous buildings of the Town Hall (the Palazzio d’Accursio) and the Basilica, built in two stages as you can see from the outside.

These squares are very busy both day and night, with a mix of impromptu concerts, terraces, students, commuters and tourists.

The Palazzio d’Accursio welcomes on its outside wall facing the Piazza del Nettuno a tribute to the Partisans who died to liberate Bologna during the Second World War. Head towards the Medieval Civic Museum along Via dell’Independenza, passing the imposing San Pietro cathedral and its beautiful, endless arcades and designer shops.

Turn left onto Via Manzoni to reach the Medieval Civic Museum , an important stop-off point for discovering the history of Bologna and the greatness of the city in those days. As you enter the museum, you come across a wooden candlestick that closely resembles a menorah.

Between the various rooms of this labyrinthine museum, three ancient Jewish tombstones and a Muslim tombstone are displayed side by side in two courtyards.

Behind the second courtyard is the Lippo di Dalmasio, dedicated to works from the Trecento and Quattrocento periods. Works from the period are on display, and the economic links between Bologna and Pistoia, which led to their mutual development during this golden age, are also explored.

The tour continues in other rooms, featuring Gothic frescoes of professors surrounded by students in this city of learning. Then there are small statues that were very popular in the Renaissance, huge books combining texts and ancient graphics, and knights’ outfits.

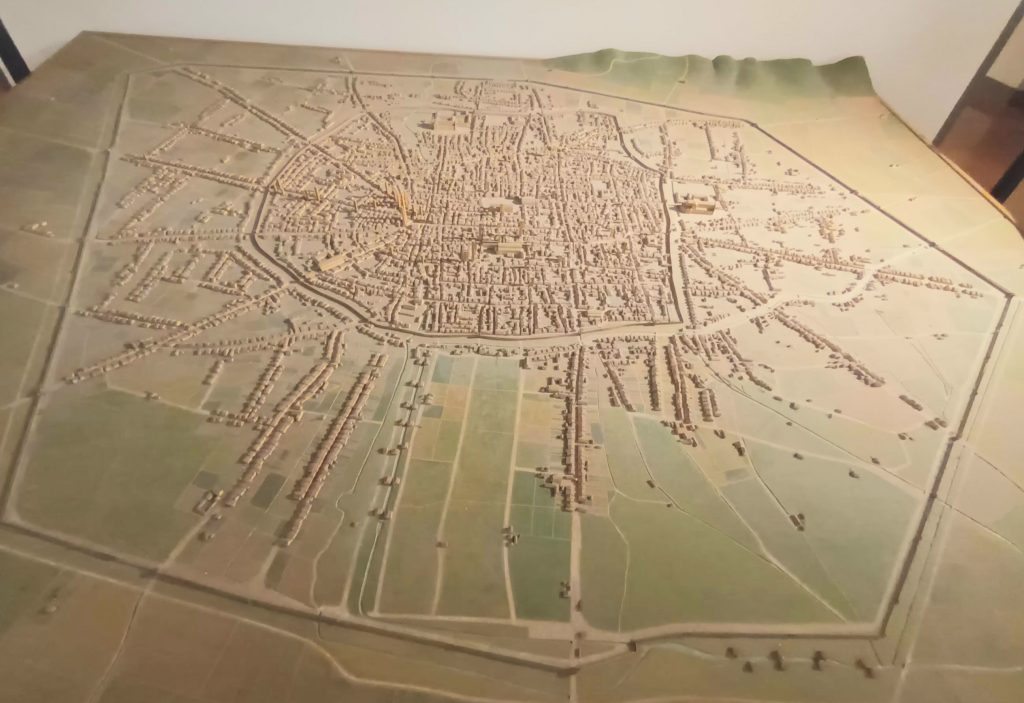

Above all, there is a beautiful model of the town in medieval times, which in the 13th century had a population of 50,000, one of the highest in Europe at the time.

On leaving the museum, head north along Via dell’Independenza and take the first street on the right. Located in Via Goito, Palazzo Bocchi was built in 1545 and 1565 by Jacopo Barozzi and Sebastiano Serlio.

It is a typical example of Renaissance architecture. The scholar Achille Bocchi founded his Literary Academy here. He had two inscriptions placed on the façade. One is in Hebrew, taken from Psalm 120: “O Lord, deliver my soul from the lying lip, from the deceitful tongue”; the other is in Latin, taken from an epistle by Horace: “Behave well and you will be king, they say”.

Continuing along Via Goito, you come to Via Guglielmo Oberdan. This is one of the two historic entrances to the ghetto. On Via Oberdan, turn into Vicolo Tibertini. Here you can see a map showing where the Jews of Bologna used to live. The old Via del Ghetto has been renamed Vicolo Mandria.

The synagogue was located on Via dell’Inferno. Entering this street, you come to Via Canonica, then Via de’ Giudei (the street of the Hebrews) and Via del Carro.

At the end of the street, you come to the famous towers of Bologna, built in the 12th and 13th centuries. The Asinelli Tower is 97.2 m high and the Garisenda Tower is only 48 m high, but it was this tower that inspired Dante. It was shortened because it was in danger of collapsing.

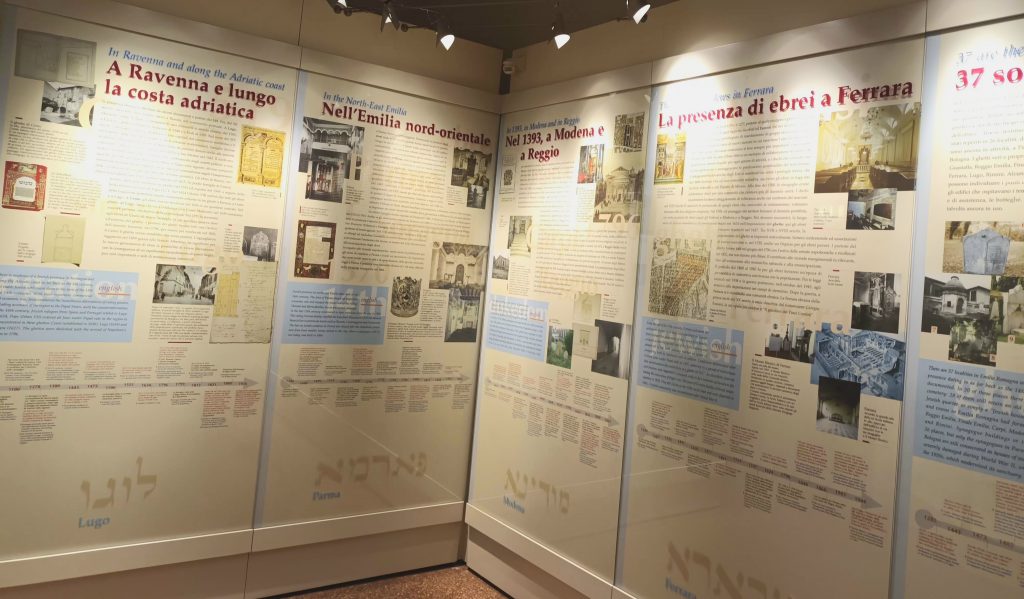

If you go up Via Zamboni, back into Via del Carro and then Via Valdonica, you will come to the Museo Ebraico di Bologna .

This Jewish museum is housed in Palazzo Pannolini, which in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was the home of the Pannolini family, producers and merchants of woollen cloth.

Inaugurated in 1999, this avant-garde museum is divided into two halls. One is devoted to the permanent exhibition and the other to temporary exhibitions. The permanent room begins with a general presentation of Judaism, the different customs, communities and their evolution over time.

The age of the Italian communities is highlighted, as is their fluctuating welcome, which has varied according to the political and religious leaders of the different eras since Antiquity. A sign indicates that Jews were present in 37 towns and villages. The tour covers both ancient and contemporary history.

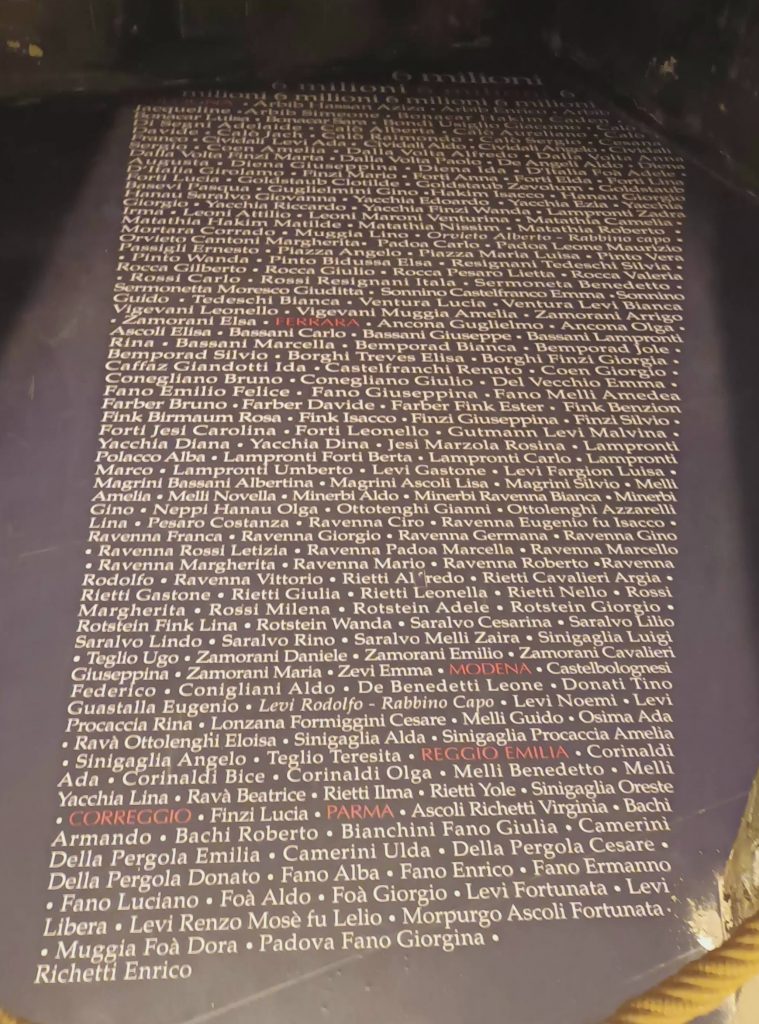

A small room is also reserved for a monument in memory of those deported from the region to the concentration camps.

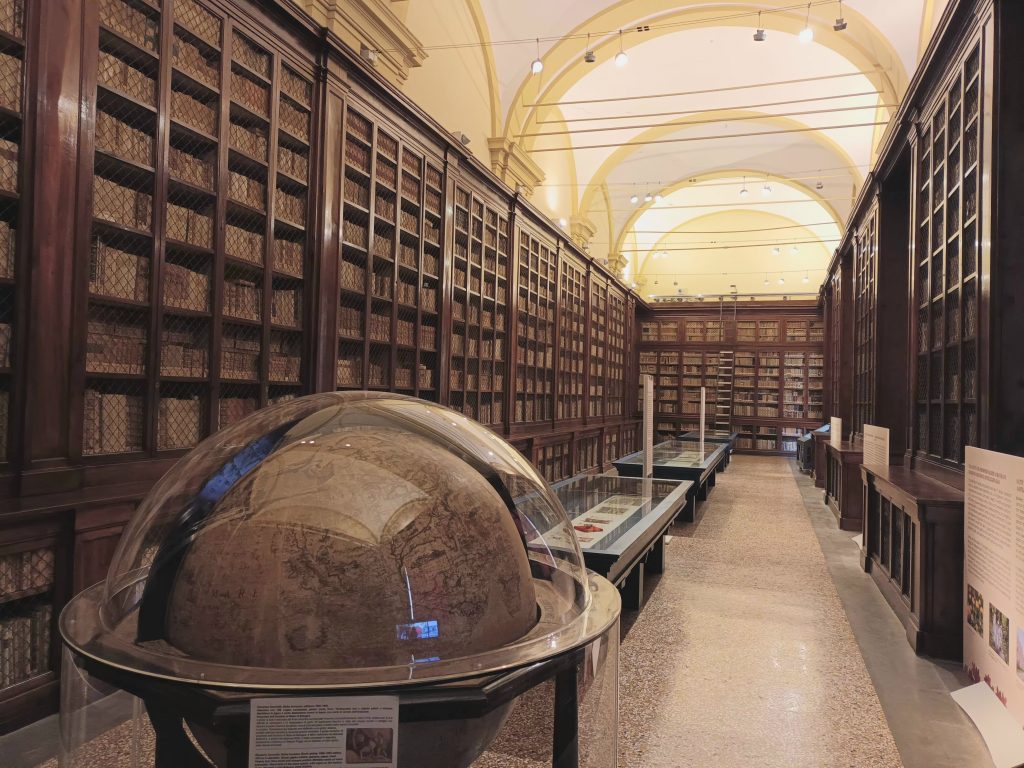

Crossing the Place Verdi, the municipal theatre and the conservatoire with its large restaurant where many students meet, you arrive at the University of Bologna .

Founded in 1088, it is the oldest university in Europe! It forms a large complex, divided into study departments: physics, natural sciences, humanities, law, literature, etc.

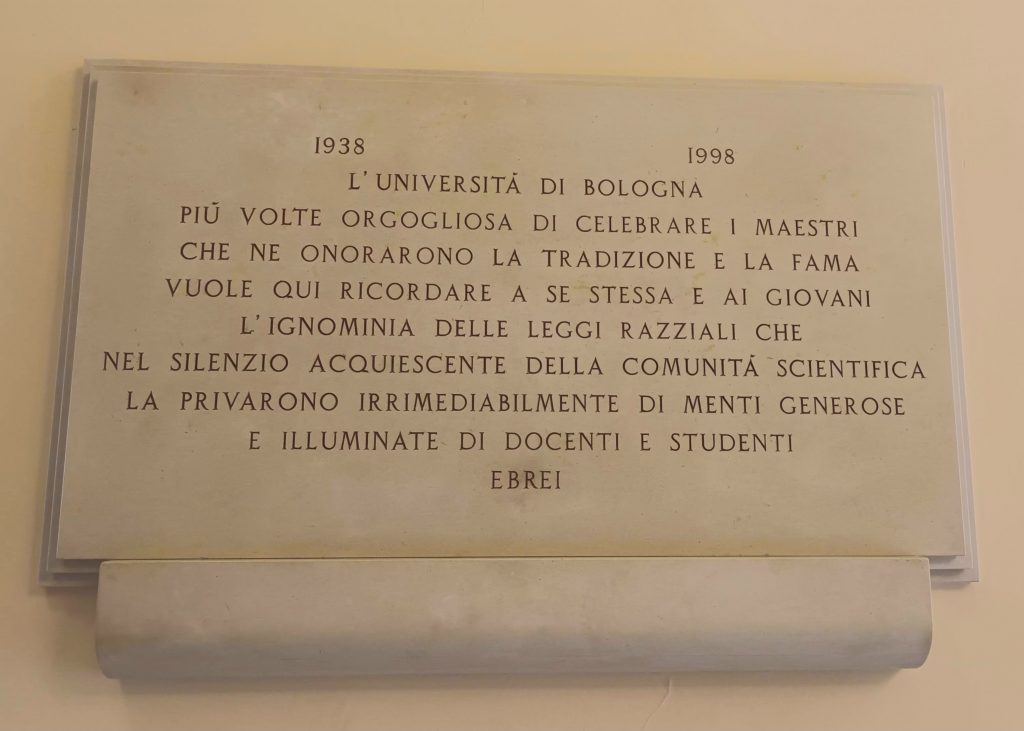

At the entrance to the university which leads to the museum, there is a plaque in memory of the Jewish students who were subjected to racial discrimination in 1938 under the Mussolini regime.

As you enter the museum on the left, you pass through various rooms celebrating scientific discoveries and all the courageous people who made these discoveries possible and supported them during political and religious struggles, encouraging encounters and curiosity. The result, of course, was the development of the university that accompanied Bologna’s status as one of the main European cities of the Middle Ages.

As you enter the museum on the right, you will see a room dedicated to military strategy, with plans of fortresses, warships and ancient cannons. Then there is an introductory science room for children. Next to this, in 2024, was a display of 20th century Japanese art.

The exhibition ends with the very impressive old university library. Next to the new library is a bust of a former student, a certain Dante!

Leaving the university, head towards Via Irnerio to arrive in Piazza dell’8 Agosto, home to a large market. To the right of this is the Parco della Montagnola. This is a garden with astonishing statues and frescoes depicting battles between animals and mythological beings, as well as historical battles. These works surround the fountain, and the many children who play there after school.

At the top left of the garden, you’ll see the Porta Galliera. Below it and to the side, ancient ruins. The railway station is just opposite. Behind it, outside the city walls, is the Shoah Memorial .

Inaugurated on 27 January 2016, it stands at the junction of Via dé Carracci and Via Giacomo Matteotti. Two steel rectangles face each other. Between them is a corridor that begins 1.60 metres wide and narrows to 80 cm, creating a feeling of oppression. The interior of the parallelepipeds is reminiscent of the dormitories at Auschwitz. The floor is made of ballast, like the stones made by Auschwitz I and II prisoners. Finally, the choice of steel, a material that rusts and deteriorates over time, is deliberate.

The Jewish presence in Pisa probably dates back to the 12th century, but could be older. Benjamin of Tudela described the city as follows: “All the inhabitants are courageous; no king or prince governs them, the supreme authority being devolved to senators elected by the people. The main representatives of the twenty Jews residing in Pisa are R. Moses, R. Haim and R. Joseph. The city has no ramparts and is located about four miles from the sea. Navigation is carried out using boats that ply the Arno, a river that runs through the city.”

In the centuries that followed, the Jews of Pisa worked in banking and trade, like many of their fellow citizens in this city, which was a crossroads of exchange between different religions and civilisations. Until the 18th century, the Jewish population struggled to maintain its numbers and declined, mainly due to economic decline caused in particular by competition from Livorno. During the Napoleonic era and especially at the end of the 19th century, the Jews of Pisa became fully integrated into social, economic and political life, with Alessandro D’Ancona even becoming mayor between 1906 and 1907. From university professors to soldiers on the battlefields of the First World War, Jews took full part in Pisan life.

As in many other European cities, Pisa experienced violent outbreaks of anti-Semitism following the importation and exploitation of the conflict between Israel and Hamas after the pogrom of 7 October. This was particularly evident at the university, where a professor who opposed the boycott against Israel was attacked by students in the middle of a lecture in September 2025.

The current synagogue, constructed in 1756, has been remodeled several times, most notably at the end of the nineteenth century.

A visit to Livorno is required in the name of remembrance, even if the urban renewal projects of the early twentieth century around the port and the bombings of the Second World War in 1943-1944 have destroyed most of the old city center, including Jewish Livorno’s Grand Synagogue. In no other Italian city did the Jews have such a significant role as in Livorno, where they were never forced to live in ghettos. They were the true founders of the city and architects of its splendor. The grand duke of Tuscany issued the edict Livornina, dated 10 June 1593, which guaranteed -for twenty-five years and with the option of the edict’s renewal- the Jews free trade and the right to settle where they chose. They were not forced to wear an identifying sign as were other Jews in the duchy, and they were permitted to have Christian servants, ride in carriages, and, under Ferdinand I, were protected from the Inquisition: “During the said period, we do not want any inquisition, inspection, denunciation, or accusation to be pronounced against you or your families, even if in the past they lived outside our dominions, whether as Christians or simply called such”.

They were a large number of Jews of Portuguese and Spanish descent in Livorno. This small coastal city, ravaged by fevers, became, in just a few years, a flourishing port where the Jewish community had a prominent role. Spanish was the official language, and Ladino was the vernacular in use especially by those expelled from Spain to Thessaloniki, as with other ports of the Levant. Gradually the Livornese Jews created a new dialect, bagitto, a mix of Spanish, Hebrew, and the local dialect; it is spoken by ederly Jews of the city even today.

The community reached its apogee in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries. Its decline began with the arrival of Bonaparte’s troops, however favorable this was to Jews throughout the rest of the peninsula: the blockade hurt the port. With Italian unification and the emancipation, the Jews of Livorno emigrated to Florence or Rome. By 1900, there were no more than 2,500 Jews in the city, a reduction by half in fifty years. The Second World War and the Nazi deportations struck a death blow to the Jewish community of Livorno, which today is reduced to some 800 members.

Completed in 1962, the new synagogue is a concrete, futuristic edifice designed by the Roman architect Angelo Di Castro that stands in the Piazza Benamozegh (the former Piazza del Tiempo) in the location of the former synagogue destroyed by bombing in 1944. The magnificent delicately carved, gilt aron from the beginning of the eighteenth century came from the old synagogue of Pesaro in the Marches.

The Marini Oratory (Draforia Marini) is located on the nearby Via Micali. During the period after the war and until the construction of the new synagogue, the oratory served as the location of worship. At the back of the square hall of the yeshiva, one can see an extraordinary gilt aron with finely carved floral decorations. It dates from the fifteenth century and probably came to Livorno with the Jews forced to flee Spain. Nevertheless, some experts date the creation of this masterpiece slightly later. The Jewish Museum is also located in this building; its collection of beautiful liturgical objects is housed in two display cases.

Siena’s ghetto was created at the same time as that of Florence in 1571. The large Jewish presence in the city is verified by documents from the beginning of the thirteenth century that mention a universita iudarum. The Jewish quarter is in the heart of the city, near the Piazza Campo and between the present-day Via San Martino and Via di Salicotto. The narrow little streets and tall houses were partly destroyed during the urban renewal projects of 1935, but certain of them have kept their original appearance, as with the buildings in Via delle Scotte near the synagogue and the names of streets like the Vicolo della Fortuna and the Vicolo della Manna.

The lovely neoclassical synagogue was built in 1756 according to the design of the Florentine architect Giuseppe Del Rosso. The construction lasted thirty years. At the center of the large, high-ceilinged hall is an elegantly sculpted wood bimah decorated with nine-armed candelabras. The windows are surrounded by moldings in the shape of ionic columns, and among the Baroque stuccowork, the walls feature fourteen verses from the Bible. The beautiful eighteenth-century aron is surrounded by marble Corinthian columns. In 2024, the Jewish community of Florence organised a fundraising campaign to save the synagogue, which had been badly damaged by the earthquake of February 2023.

Facing the synagogue, in Via degli Archi, stands the old fountain of the ghetto, which once boasted a statue of Moses. The statue was removed in the twentieth century due to pressure from indignant Orthodox Jews, who saw the statue as a transgression of the law forbidding representation of the human figure. It is now located in the local museum.

At the gates of the city on Via Certosa, one can see the old Jewish cemetery, whose oldest graves date to the sixteenth century.

Located at the extreme south of Tuscany among the hills and cypresses, the borough of Pitigliano rises from a rocky pinnacle. Once called “little Jerusalem” by Tuscan Jews, the nickname points to the historical importance of Pitigliano’s Jewish community here, formed by those fleeing the Papal States after the edicts of 1555.

The Jews remained here for almost four centuries, formally occupying a ghetto after 1622, but trading or even farming in almost perfect tranquility. This calm was interrupted, however, in 1799 by anti-French violence subsequently directed at the Jews, who, with their new ideas, were accused of being in sympathy with the French. Of the 3189 residents registered in the town census of 1841, 359, or roughly 10%, were Jewish. After the emancipation in 1859, the Jews in Pitigliano stayed until the beginning of the twentieth century, their positive sentiments evident in the custom of naming their children Garibaldi or Mazzini, names of the heroes of Italian reunification. Eventually many residents departed for Florence or the capital and the community languished.

The best white kosher wine in Italy and an ancient synagogue are among the remains of the Jewish community in Pitigliano. The synagogue, which dates from the sixteenth century and was last remodeled in the eighteenth century, was crumbling by the 1960s. Restored and reopened in 1995, it stands in the former Jewish quarter at the foot of the Orsini Castle beside the former bread oven. Only one wall of the synagogue, that of the women’s gallery, has remained intact. The rest of the synagogue has ben carefully reconstructed with the gilt stucco, holy inscriptions in Hebrew, and plaques commemorating the visit of the grand dukes Ferdinand III and Leopold II to the temple at the beginning of the nineteenth century.

The former ghetto of Florence was located in the heart of the old city center near the market in a zone totally destroyed and the end of the twentieth century, situated today between Via Brunelleschi, the Piazza della Repubblica, and Via Roma. Bernardo Buontalento, the grand duke’s architect, was commissioned to design the ghetto. The streets accessing the residential blocks were walled, with the exception of two gates that were closed each evening.

As in Siena, in Florence Jews from all the villages and towns of Tuscany were confined inside a labyrinth of alleys and courtyards. The Jews were excluded from guilds, and hawking used clothing was the only occupation open to them. They remained in the ghetto a=for almost three centuries, until 1848. Its two synagogues, one with Italian services and the other with Spanish, were destroyed at the same time as the ghetto at the end of the twentieth century. Shortly before the opening of the Grand Temple, two small oratories were created in 1882. In use until 1962, one oratory held services in Italian; the other followed an Ashkenazic liturgy. Both of them are commemorated in a plaque on the building at 4 Via delle Oche, which was the offices of the Mattir Assurim confraternity.

The imposing neo-Moorish Grand Temple (Tiempo Maggiore) was unveiled in 1882 after eight years of construction. Designed by Marco Treves with the assistance of architects Mariano Falcini and Vincenzo Micheli, this synagogue with its majestic pink and white stone facade is dominated by a large green dome and two matching minarets on each side. The Tablets of the Law crown the pediment. The rich Moorish-style interior is sumptuously decorated with arcades of slender columns, and in the center, there is a semi-circular apse where the aron and the bimah are enthroned, separated from the rest of the prayer hall by a finely wrought grille. The mosaics and frescoes of gold and azure are the work of Giovanni Panti. During the war, the Nazis used the temple as a military garage and attempted to dynamite it during their retreat, fortunately without substantial damage. Carefully restored, the synagogue was later victim to the great flooding of the Arno River in 1966, which filled it with seven feet of water. A large portion of the 15,000-volume library was severely damaged.

The facade of the Basilica Santa Croce

The facade of the Basilica Santa Croce is decorated with a large Star of David that will probably arouse your curiosity. In their Guida all’Italia Ebraica (Guide to Jewish Italy), Annie Sacerdoti and Luca Fiorentino tell of its strange origin: “In 1860, it was decided to renovate the church’s thirteenth-century Gothic facade with polychrome marble. The work was entrusted to the architect Nicolò Matas, a Jew from Ancona who incorporated the large star as an element of the decoration. No one paid any attention to the architect’s Jewish origins, even after he specified in his contract that he would not work on Saturdays. When he died, he put the Jewish community and the Franciscans in a difficult position by stating in his will his wish to be buried in the basilica. A compromise was finally reached: he was interred in a marble sarcophagus just outside the church under the flight of stairs facing the main entrance.

Opened in 1981, the Jewish Museum is on the second floor in a vast room divided into two parts: one houses a collection of photos, visual witnesses to Jewish life in Florence, and the other contains beautiful religious objects, especially silver pieces and textiles. You can also admire a beautiful old rimmon dating from the end of the sixteenth century. At the museum exit, a large plaque commemorates the 248 Jews from Florence who were deported and died in the death camps or were executed.

Interview with Emanuele Viterbo, Head of the Jewish Community of Florence

Jguideeurope: How was the Jewish Museum of Florence created?

Emanuele Viterbo: The design of the Jewish Museum in Florence, strongly backed by Rabbi Fernando Belgrado, was initiated in 1981as a result of the donation of Marta del Mar Bigiavi. The first exhibit occupied the first floor in a room behind the women’s gallery and included the historical section and the furniture and home furnishings of synagogue worship. The project was designed by the architect Alberto Boralevi, with the exhibition design by Dora Smooth. The second part of the museum, opened in 2007, is located on the top floor, and was designed by the architect Renzo Funaro in collaboration with the architect Michael Tarroni and was set up by Dora Smooth and for the textile industry section by Laura Zaccagnini.

This time, the museum was divided into two sections: the first floor were the furnishings ceremonial use in the synagogue, in the latter have been moved to objects for domestic worship. One room, curated by Renzo Funaro and Liana Funaro, was dedicated to the Holocaust.

The choice of rooms and Museum set up has been done based on museological and conservation considerations. First, it was decided to set it in the Temple which, due to its artistic and historical importance for its monumentality, not only represents the ideal, but it has become an integral part of the course of Jewish History in Florence. The cellars, while beautiful and impressive, but who did not have security policies because of the danger of floods (the last of which, in 1966, came up to two meters in height above the height difference created by the steps outside), have been discarded. It is a relatively small museum, but very impressive.

The collections of the Jewish Museum in Florence are arranged on two floors inside the synagogue.

The first section documents the history of the Jews in Florence over the centuries and their relationship with the city. In the display cases are furniture, textile, and silver, used for ceremonies synagogue between the end of the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. On the second floor, in a room with a beautiful view on the inside of the temple, there are objects and furnishings of domestic and private devotion, illustrating the highlights of the festivities and religious life of a Jew such as birth, marriage and religious ceremonies. Many of these items are gifts from Jewish families who wanted to testify so their attachment to the Community. Important figures in the community in the knight David Levi, who left his fortune to construct the building of the synagogue, and that of Rabbi Shmuel Zvi Margulies, of Polish origin, who renewed the Italian Rabbinical College and brought it to Florence.

The tour continues with a film that introduces the history of the community in the past two centuries, and a room of Remembrance, where photos and archival records of the life of the Jews in Florence, the newfound equality after the age of ghettos, persecution, to following the racial laws, and deportation to the death camps, to the rebirth and reconstruction after the war, are displayed. A computer room connected to the major Jewish museums in the world and puts the Florentine Jewish life in a very broad context.

The museum consists of a first section, which documents the history of the Jewish Florentine by birth, in 1437, at the time of the founding of the Ghetto, its extension in 1571, and again from 1704 to 1721, until the demolition of the last decade the nineteenth century. This is illustrated through photographs of plants, pictures of the ghetto destroyed and ancient synagogues. Newer images illustrate the story of the design and construction of the Temple. There is also a nod to the other sites of Jewish Florence.

Most of the furnishings are from two synagogues in the Ghetto, that the Italians opened after the creation of the district intended to house arrest by the Jews in 1571, and the Spanish and Levantine, opened a few years later, which objects were added that belonged to the synagogues of Arezzo and Lippiano -communities that are now extinct- and by the synagogue, for which they were specially made. Considerable space is devoted to the ornaments of the Sefer Torah, the scrolls of parchment on which the Hebrew bible is written.

The second part of the museum, opened on the top floor in 2007, is a collection of objects and drawings that summarize the origins of the Jewish community in Florence.

If the Chevalier David Levi is the symbol for excellence of Italian Jewry (illustrated in “the Italian,” a beautiful portrait by Antonio Ciseri in 1854), the core of most influential Jews were of Sephardic origin, originating in Spain, subsequently, the countries of North Africa and the Middle East. Here you can view significant objects that illustrate the most important moments of life and religious holidays, with personal or household furnishings organized by type and according to different occasions. The family has a very important role in the Jewish religion.

Most of the six hundred commandments (mitzvot), that every jew is obliged to follow, are put into practice in daily life. Many of the exhibits in the museum follows the story of an important Florentine family, the Ambron-Errera family, whose history can be witnessed here.

Tempio Maggiore is considered one of the most beautiful synagogues of Europe. How was its style imagined?

The synagogue of Florence was inaugurated in 1882, not longer after the emancipation of the Italian Jews which was proclaimed in 1861 when the Kingdom of Italy was established. The Florence synagogue is one of Europe’s finest examples of a blend of the exotic Moorish style with Arabic and Byzantine elements that characterize the white travertine and pink limestone façade, the copper-cladding on the central and lateral domes (originally they were gilded), and the massive walnut doors. The style is also reflected in the interior decorations and furnishings. The community had been debating about a new synagogue since 1847, but the lack of funds made it impossible to take any concrete steps. Then, in 1868, Cavalier David Levi bequeathed the money for the construction of a “Monumental Temple worthy of Florence”. Two years later, in 1870, three architects, Mariano Falcini, Marco Treves and Vincenco Micheli, were appointed to design the temple.

The location was finally selected after lengthy discussions between the factions that wanted it in the city centre and the group that preferred a site outside. The latter prevailed, and the choice fell on the “Mattonaia” district which, though still within the city walls, was not completely developed, indeed there were still many parks and gardens. The new Temple was opened on 24 October 1882.

Two seemingly opposite, but actually related approaches influenced the design. On the one hand there was the influence of Christian churches and the Old Spanish synagogues, and on the other was desire to express Jewish identity through a distinctive architectural style. The final result, the “child” of nineteenth century Eclecticism, was something new that combined Moorish, Byzantine and Romanesque elements.

How did the Resistance save the Tempio Maggiore from destruction during the war?

In 1938 the Fascist regime enacted racial laws which deprived Jews of work and schooling, among other restrictions and dubbed them an inferior race. In September 1943, the Nazis effectively seized control of a large part of the country. Some Jews saved themselves by fleeing abroad while others went into hiding and were sheltered by the local population. In total, 9,000 Italian Jews were deported or killed, more than 500 of them were from Florence. After the war, the Jewish school was reopened and the Synagogue was renovated.

The Jews in the capital of Italy are perhaps the oldest Romans of all. They have settled in the same ancient neighborhoods in the heart of the Eternal City for 2000 years, making their homes in the former ghetto, in Trastevere, and on both sides of the Tiber River where it is crossed by the Ponte Fabricio or Ponte Quattro Capi.

Not only one of the oldest communities of the peninsula, Roman Jewry also represents one of the most important, lively, and deeply rooted communities today, with its own dialect containing Hebrew words and particular culinary tradition. This 2000-year-old homeland, without equal with the exception of Israel, preserves numerous monuments dating from all periods, from the Jewish catacombs or the Ostia Antica Synagogue to the Grand Temple constructed at the beginning of the twentieth century on the location of the former ghetto.

A visit to Jewish Rome merits at least five days. In this Christian capital, the rich remains of Jewish history proper are augmented by many things that attest to papal policy regarding the Jews. Some for the better and most for the worst, these physical records conditioned Jewish life in Rome -if not in the west as a whole.

Certain Jewish dishes still make up part of Roman gastronomy and appear on the menus of numerous restaurants. A case in point is carcioffi all giudea (artichokes Jewish style): the artichoke is fried in oil until the small leaves are marvelously crispy. The traditional cuisine of the Eternal City’s lower classes is based on inexpensive ingredients, lower quality cuts of meat, and lots of vegetables. These characteristics are more markedly noticeable in dishes typical of the Jews in the capital, confined for three centuries in the ghetto.

Many recipes, notably for fish, are agro-dolci (bitter sweet) with sugar, vinegar, pine nuts, and raisins, representing a tradition dating back to the Roman period. Fried dishes make up the lion’s share of typical Roman cooking; aside from the artichokes already mentioned, these include fiori di zucchine (fried zucchini blossoms stuffed with mozzarella and anchovies) or the fritto di baccalà (salt cod croquette). The pasta and soup recipes are hearty, stick-to-the-ribs dishes like the traditional ceci e pennerelli (chickpeas and leftover meat morsels) simmered on a low fire for three hours.

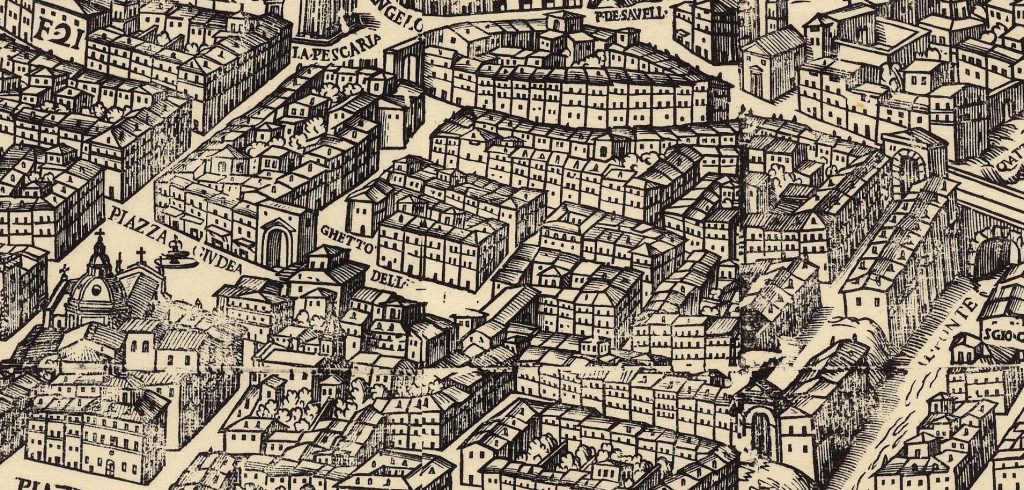

The former ghetto

The quarter where the Jews were forced to reside for three centuries until 1870 is at the center of the Italian capital, between the Largo Argentina, the Capitoline, and the Tiber. Almost nothing remains of the stifling, cramped streets of the old ghetto, which was destroyed, sanitized, and reconstructed in the first years of the twentieth century. The neighboring narrow streets, such as Via della Reginella or the beginning of Via Sant’Angelo in Pescheria, give an idea of what the lives of the Jews in the city were like for three hundred years.

Portico d’Ottavia, constructed by Cecilius Metella in 146 B.C.E. remains one of the symbolic places of the former Roman ghetto. The remains of the fluted columns rise from among the enormous paving stones surrounding the large Temple of Juno on Via del Portico d’Ottavia.

Restaurants set up their sidewalk tables from which the regulars take in the fresh air. This portal marks one of the five former entrances to this forced residential quarter. It was customarily barred at night with a great iron chain. The Piazza delle Cinque Scole surrounds a fountain by Giacomo della Porta (erected in 1591, rebuilt in 1930) commemorating the five synagogues of the former ghetto (Catalana, Castigliana, Tempio, Siciliana, and Nova).

These were all located in a single building that has since vanished but which was located on the present-day square at number 37. The current building is constructed on the site of the former Platea Judea, or “grand square”, divided into two halves by the ghetto wall, which was the intersection of two ancient thoroughfares of the Jewish quarter, Via Pescaria and Via Rua.

It was in the Platea Judea, at once inside and outside the ghetto, that the economic activities permitted to the Jews of Rome took place. These activities included trade in old clothing, used goods, and some artisanal work. In periods of tolerance these stalls were permitted to open on Sunday and the villagers who had come to the city and did not want to lose a day would come her to make their purchases.

The Piazza delle Cinque Scole, with its many shops, remains the heart of the quarter. Be sure not to miss a pasticceria called Boccione, which sells cakes typical of the Roman-Jewish tradition such as its extraordinary cheesecake made from ricotta. Menorah , a nearby bookstore, is well stocked with both old and new books on Judaism in Italian, French and English.

Heading back up this narrow, shadowy street toward the Piazza Mattei, with its magnificent “tortoise” fountain constructed in 1581-84, it is possible to get an idea of what the ghetto was like back in those ancient times. The blocks of buildings situated between Via Reginella and Via Sant’Ambrogio became part of the Jewish quarter when Pope Leon XII designed to enlarge it a little in 1823.

Completely on the other side of the former Jewish quarter, and heading in the direction of the Tiber and the Grand Temple, stands the small church of San Gregorio all Divina Pietà, constructed in the eighteenth century opposite one of the ghetto gates. Its facade features an inscription in Latin and Hebrew citing the prophet Isaiah speaking “to those rebellious people who act according to ideas in a way which isn’t good, to those people who continually provoke my anger”. This was one of the places where each Sunday, representatives of the Jewish community were obliged to listen to the Catholic Mass.

The Grand Temple

The zinc dome of the Grand Temple rises 151 feet above the street and can be seen from anywhere in Rome among the other baroque domes of the many churches in the Eternal City.

It is easily recognized by its square shape. Constructed between 1901 and 1904, hardly more than thirty years after the closing of the ghetto, the Grand Temple celebrates the Italian Jews and their extraordinary integration. The style of the Temple is oriental, though some have ironically described it as neo-Babylonian.

“Between the Capitoline and the Janiculum, between the monument to Victor Emmanuel and that of Garibaldi, the two great masters of our Italy, stands this majestic temple surrounded by the pure, free sunshine that signals liberty ad love”, declared Angelo Sereni, president of the Jewish community, whose perhaps florid rhetoric on the occasion of the building’s opening nevertheless expressed the state of mind of his fellow believers at the time.

Surrounded by a lovely garden with palm trees, the building was constructed on a large, 32000 square foot piece of land made available by the demolition of the former ghetto, which had been completely razed shorty before and replaced with the large liberty-style buildings. Since at the time there were no licensed Jewish architects, its two designers, Vincenzo Costa and Osvaldo Armani, were non-Jews.

The facade is adorned wit palms and has three large windows. Near its top, the building features a tympanum decorated with the Tablets of the Law, above which stands a seven-branched menorah. The interior of the main hall is sumptuous, with marble columns in an oriental style. The aron, above the steps of a platform at the end of the nave, evokes the altar of a church, like many of the synagogues constructed just after the Jews’ emancipation. Abundant light pours in through the large liberty-style windows. The interior of the large dome is decorated with oriental-style paintings (palms and starry sky) by Annibale Brugnoli and Domenico Bruschi. In the halls of the Grand Temple many of the objects historically used in the five synagogues of the former ghetto have been assembled and are on display.

Especially noteworthy are the magnificent marble-columned aronot from the Siciliana Synagogue of 1586 and that of the Castigliana Synagogue of 1642. The Spanish Temple, occupying since 1932 a large part of the Grand Temple, perpetuates the tradition of Jews who came from the Iberian Peninsula, while the majority of the services are now in Italian. The hall with its aron facing the tevah evokes the atmosphere of the former Roman synagogue that has since disappeared. The Jewish Museum occupies one of the wings of the Grand Temple. Numerous silver religious objects, circumcision chairs, candelabras, fabrics, and manuscripts, including three volumes of poems in Judeo-Roman by Crescenzo del Monte (1868-1935), are on display in two vast rooms.

Tiber Island and Trastevere

The only island in the Tiber River as it snakes through Rome, Tiber Island was consecrated by the ancient Romans to Aesculapius, the god of medicine. Since the Middle Ages, it has been the site of the hospices or hospitals. The island links the Jewish quarter on either side of the river; thus in the eleventh century both the Ponte Fabricio and the Ponte Quattro Capi were alternately called the Pons Judeorum. In 1870 the confraternities of the former ghetto settled here in order to create aid organizations for the newly emancipated Jews. One one side of the island’s central street facing upstream stand the Israelite hospital and the Panzieri-Fatucci oratory, called the Tempio dei Giovanni. The nineteenth century wooden aron of the oratory originally came from the five synagogues. The brightly colored stained-glass windows representing Jewish holidays were completed in 1988.

One the other side of the river is the Trastevere (literally, “beyond the Tevere [Tiber]”) district. In his travel journals during a trip to Italy in the twelfth century, Benjamin de Tudela, a Jew from Navarre, recounts that numerous Jews lived here during imperial Rome and during the medieval period. Traces of this past that survived the imprisonment of the Jews in the ghetto in 1555 are rare. At 14 Vicolo de l’Atleta stands a small brick building with two arches. A Hebrew inscription on a column of the loggia and a well in the courtyard indicate that it probably functioned as a synagogue in the Middle Ages.

The former cemetery was in the area of Porta Portese, where the flea market is held every Sunday. After 1870, a large part of Roman-Jewish life once again moved to the Trastevere district, where today the majority of the community’s institutions are concentrated, including Il Pittigliani , the former Jewish orphanage, which has been transformed into a cultural center with a kosher snack bar and library possessing numerous documents on Jewish life in the capital.

The headquarters if the Union of the Italian Hebrew Communities is located on the other side of Viale Trastevere, the large avenue dividing the district. It includes a documentation center on Jewish heritage and, a little further along, at number 14 and 12, the Hebrew day care and primary school respectively. The Roman poets and Folklore Museum merits a brief visit to see the three paintings by Ettore Roesler Franz (1845-1907) depicting scenes of everyday life in the ghetto.

The Forum