The call major, which was active between the twelfth century and the riots of 1391, is Spain’s best-preserved Jewish quarter and the easiest to visit. It comprises a small zone between the Palau de la Generalitat and the calles Banys Nous, Sant Domenec del Call, Sant Honorat, Arc de Sant Ramon del Call, Sant Sever, la Fruita, Marlet, and del Call. The synagogue was at 7 Calle de Sant Domenec del Call, next to the houses of the rabbis Nissim Gerundi and Isaac bar Seset Perfet.

At number 1 on Marlet Street, you will discover a 13th-century Hebrew inscription whose original was discovered in 1820 and preserved in the City’s Historical Museum, reminiscent of a pious foundation in tribute to Rabbi Samuel ha-Sardi. The stone states “Pia Foundation of Samuel ha-Sardi; its light shines for eternity “

The call menor, created in 1257, is located outside the walls, along the present carrer Ferran. On the site of the synagogue, the church of St. Jaume was built in 1595. This district underwent profound changes in the nineteenth century, and there remains today no trace of a Jewish past. The cemetery is listed since 1091 on the hill of Montjuic, a name whose origin isn’t known (perhaps “the Mount of the Jews”). On its site stands today the Olympic Stadium. In 1945, excavations made it possible to find some thirty tombstones, exhibited at the Military Museum installed in the old castle, as well as four rings and earrings on display at the City’s Historical Museum. It is also known that Jewish winemakers produced kosher wine at this location.

Records of the cemetery of Montjuic, a name of uncertain origin (possibly “Jews’ Mountain”) go back to 1091. Today, the site is occupied by the Olympic stadium. In 1945, excavation brought to light some thirty headstones, now exhibited in the Military Museum (Museo Militar) housed in the old castle, as well as four rings and earrings that can be seen in the city’s Historical Museum.

You will find fragments of Hebrew inscriptions on the houses of Carrer Montcada and Condes de Barcelona. On the Plaça del Rei, where the first autodafé of the Inquisition took place in 1488, stands the Palau Reial Major: it was in one of its rooms that the famous controversy between Nahmanide and Pau Cristiani took place in 1263 , in the presence of King Jaume I. On the other side of the square, the archives of the Crown of Aragon preserve a precious and vast documentation on the history of the life of the Catalan Jews; there are also the remains of a tombstone of Montjuic.

The old synagogue, or major synagogue of Barcelona is in the old medieval Jewish quarter. The building dates from the 6th century and is to date the oldest synagogue found in Spain. The building’s foundations date back to Roman times, and you can see remnants of this past on the interior walls of the synagogue. After the sacking of the Jewish quarter on August 5, 1391, the building passed into the hands of the king, and, little by little, its original function and location were forgotten. It was not until 1996 that the historian Jaume Riera i Sans located exactly the building of the old synagogue.

The association Call de Barcelona has recovered the building and proceeded to its renovation. In 2002, the major synagogue reopened in the form of a cultural center and museum. To access it, you have to go down stairs about 2 meters below the current level of the street. The building strikes by its modest dimensions: about 60 m2, which agrees with the restrictions on non-Catholic places of worship of the time. Note that the association offers various complementary activities to visit the major synagogue, such as walks in the Call Jueu, the medieval Jewish district of Barcelona.

The city of Barcelona has suffered an upsurge in anti-Semitic attacks since the pogrom in Israel on 7 October 2023.

The presence of Jews in Besalú is attested in a document from 1229 in which Jaume I the Conqueror reserves to them the function of moneylender. In 1342, the community, hitherto linked to the one in Barcelona, became independent. In those days it numbered 200, a quarter of the total population, and lived side by side with the Christians. We have no information about 1391 and the pogroms. Not until the bull issued by the antipope Benedict XIII was a call created around the synagogue and the Plaça Mayor (Portal Belloch, Capellada, Carrer del Pont, Carrer del Forni i Rocafort). In 1435, the Jews abandoned Besalú for Granollers and Castelló d’Empúries.

A mikvah was discovered in 1964 on the site of an old dye manufacture. Since 1977, development and restoration works have made it accessible to visitors. It dates probably from the thirteenth century and is the only Romanesque mikvah in Spain. Thirty-six steps lead down to a small rectangular room in the basement. In keeping with tradition, the bath has a fine vault overhead and is lit by a window in the eastern wall. This mikvah probably belonged to a synagogue that stood in the site of the garden on today’s Plaça dels Jueus (Jew’s Square). From here there is a fine view of the Fluvia River and its Roman bridge.

Gerona was the second most important community in Catalonia, both for its size (1000 men and women in the twelfth and thirteenth centuries, but only 100 or so in the fifteenth) and for the quality of its scholars. Gerona was the home of Nahmanides, Johan ben Abraham Gerondi, Azriel of Gerona, Bonastruc da Porta, and Isaac the Blind.

Gerona’s Jewish history has been famous since 1980, when the discovery of Sant Llorenç, a forgotten lane in the call (the Catalan equivalent of a judería), brought to light a vivid image of Jewish life in the old town. Up to the thirteenth century, the Jews lived in houses that belonged to the cathedral chapter, around today’s Plaça dels Apostols. They gradually extended the quarter around the Carrer de la Força. The area is best toured on foot.

Gerona had three synagogues in quick succession. The first stood near the cathedral and was demolished in 1312 during construction work. The second was in the Carrer de la Força, probably at numbers 21-25, but it was closed in 1415 after the bull of Pope Benedict XII. The third synagogue was in use at the time of the expulsion and stood at 10 Carrer de la Força, where the municipality has set up de Bonastruc de Porta Center for Jewish Studies (Centro Bonastruc de Porta). It is possible this building also housed the kosher butcher shop. The first phase of restoration work has revealed the handsome brick architecture. A little further down the road, on the corner of Carrer Cundaro, stands the house inhabited by Nahmanides.

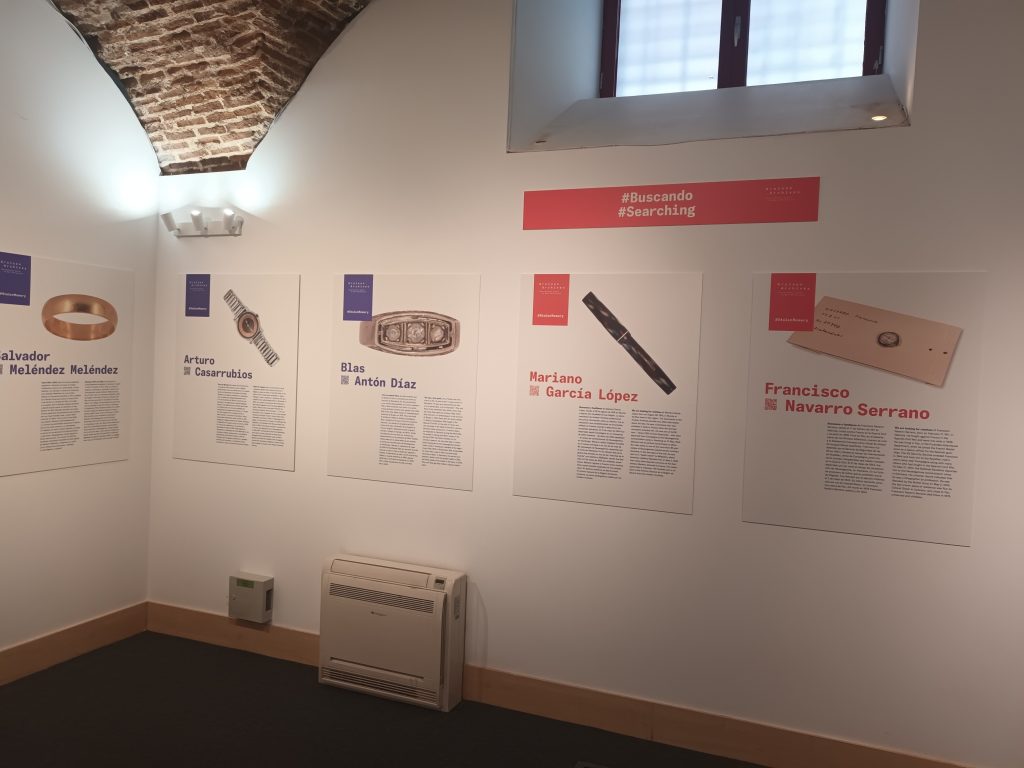

The cemetery was located on a hill still called Montjuic (Jews’ Mountain). In 1492 the Jews donated it to the knight Joan de Sarriera, who had helped the community during the anti-Jewish riots. Subsequent owners used the tombstones as building materials. Many of them have been retrieved and studied and are now superbly displayed in the Archaeological Museum (Museu Arqueologic), located in the cloister of Sant Pere de Galligants. Others are in the historical museum of Gerona (Museu Historia de la Civtat). These moving vestiges are notable for the quality of their sculpture and their texts.

Note also the jambs at the entrances to the old Jewish houses. At 5 Carrer de la Força, for example, the niche made for the mezuzah can still be seen. The Seminary Biblical Museum has a fifteenth century one found at 15 Carrer de la Força in 1886.

The municipal archives (Arxiu Municipal) displays some notable documents and contracts written in Hebrew and Judeo-Catalan as well as old book bindings made from Hebrew parchment.

In the fourteenth century, and up to 1492, there was a large community in Castelló d’Empúries living around the Plaza Llana, in the calles de la Judería, del San Padre, and Peixetiries Velles.

There are two known cemetery sites. A tombstone found in one of them can be seen in the local museum (Museo Parroquial), while seven others have been reused in various constructions.

In the fifteenth century some 15% of Tudela’s population were Jews. There were two quarters, one around the Zaragaza gate, the other within the castle walls, but nothing remains of these sizable communities.

Visitors can, however, go to the Ribotas landing stage at the confluence of the Ebro and Merchando, where Benjamin de Tudela set off on his long journey. The journey which enabled researchers and historians to know so much about the state of Jewish communities and important figures of that era around Europe and even further east. A street was named in his honour.

Benjamin de Tudela

In the twelth century the tireless explorer Benjamin de Tudela spent some ten years traveling the world and filling his notebooks with impressions. He visited Zaragoza, Tortosa, Tarragona, Barcelona, and Gerona, journeyed through Roussillon and Provence to Marseille and from there sailed to Italy (Genoa, Pisa, Lucca, Rome, and Salerno) before going on to Corfu in the Aegean and then Constantinople. Reaching his gateway to Asia Minor, he hastened on to the Holy Land, then controlled by the Crusaders, and traveled to Jerusalem and Nablus before going to Damascus and Aleppo. He continued along the valley of the Tigris to Baghdad, then went to Cairo and from there via the Sinai back west to Sicily and Rome. Back in Europe, he felt the compulsion to head for Verdun and Paris, where he ended his journey. In addition to his own observations, Benjamin de Tudela also fleshed out his account with summaries of conversations with his fellow travelers about more remote lands such as Russia, Bohemia, and China.

The town of Vitoria had 300 Jews in 1290 and 900 on the eve of the expulsion -the equivalent of 6 or 7% of the total population. Their main activities were tax collecting and medicine. In 1492 they took refuge in Bayonne across the French border, where, even today, the Jews think of themselves as the descendants of those in Vitoria.

The most surprising vestige of the Jewish presence is the old cemetery, or Judizmendi (Jews’ Mountain). On 27 June 1492, the town council signed an agreement with the community, undertaking to respect and maintain the cemetery.

This accord was observed until 1952, when the town government obtained authorization from the Jewish community in Bayonne to transform it into a public garden. A monolith recalls this unusual piece of history.

Probably the most interesting judería in Galicia, Ribadavia has kept its old Jewish quarter despite later urban developments. Although it is known Jews were there as far back as the tenth century, few documents about the life of their community remain.

The old synagogue is the building with crests on its facade in the Rua Merelles , which runs between the Plaza Mayor and Plaza de la Madalena. In September, the locals organize a Festival of the Jews with a costumed parade.

The earliest mention of Jewish shopkeepers in Aguilar de Campó, situated along the trading route toward the port of Cantabria, is from 1188.

A Hebrew inscription can still be seen under the town’s coat of arms on the old door of the Reinosa . It tells us that on 1 June 1380, work on building the door began, paid for by Don Caq (Isaac) ben Malak and his wife Bellida. The text is in Hebrew and Castilian, with Hebrew characters (aljamiado).

A small Jewish community lived in Puente Castro until the twelfth century. It disappeared during the wars between Castile and León.

The cemetery has yielded more than a dozen magnificent tombstones. Three of them have been on permanent loan at Toledo’s Sephardic Museum since 1969, and a fourth can be seen at the diocesan museum in León. A fifth one, at the Archaeological Museum of León (Museo Arceologico de León), was discovered in fragments in 1983 and probably dates from 1100. Its elegantly written inscription reads: “Cientos the Saint may be blessed and absolved; take him in Your mercy and resurrect him to the life of the future world, amen.”

The village of Amusco is known to have had a community of some 300 Jews in the fifteenth century. The old synagogue is still here, surprisingly positioned on the village square next to the church and village hall; it is now the Synagogue Café (Café de la Sinagoga).

The medieval synagogue was at basement level. Its powerful vaults are supported by six arches. Its design is not surprising since in those days synagogues were not allowed to be too high or luxurious. Today it is a banquet hall.

Segovia was home to one of the biggest communities in the Kingdom of Castile. It produced important figures like Abraham Senior and his son-in-law Meyer Melamed, who served the Catholic monarchs up to 1492. Segovia also saw a violent anti-Jewish movement under the influence of the Santa Cruz convent and subsequently as a result of the “Holy Innocent Child” affair at La Guardia.

It is easy to find the old Jewish quarter, even if many of the buildings are more recent in origin. In particular, explore the streets of the Judería Vieja y Nueva. The synagogue has been transformed into the church of the Corpus Christi convent. It was, in all probability, built in 1410. In the nineteenth century, fire followed by negligent restoration destroyed the specifically Jewish part of the structure, apart from the original plan and a few pieces of stucco now in the local museum (Museo Provincial). In the Calle de la Vieja Judería, the Franciscan convent was built on a set of sixteenth and seventeenth century Jewish houses, including the home of Abraham Senior.

The “Sephardic Jerusalem” is known around the world for the beauty of its synagogues and its Jewish quarter. The memory of the community has remained vivid in Toledo; historians have from the thirteenth and fourteenth century onward been able to supply fairly precise information about the location and history of the city’s Jewish community. Toledo is a city of great historical and artistic importance and is listed here as a World Heritage Site.

At the time of its greatest splendor, just before 1391, Toledo had ten synagogues and five to seven yeshivot. In 1492 there were five grand synagogues, two of which survive: the Tránsito, now the Sephardic Museum, and Santa María la Blanca.

The Tránsito Synagogue

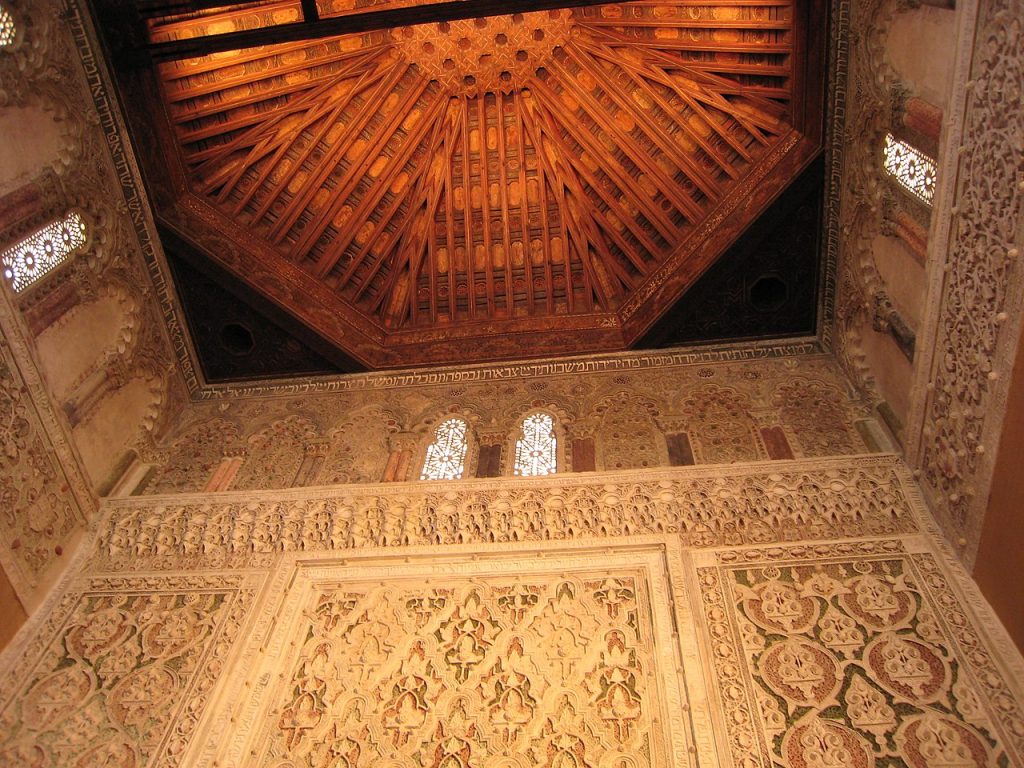

The Tránsito Synagogue was built in 1357 at the order of Samuel Levi, treasurer to King Pedro I. Archaeological finds suggest this imposing edifice was erected on the site of an older synagogue. In 1492, the Catholic monarchs donated it to the Calatrava military order, which transformed it into a priory. During the Napoleonic Wars is served as barracks. In 1877, it was declared a national monument. When Spain’s Jewish community revived, the outbuildings became the Sephardic Museum.

As is often the case, the brick facade is austere, without decoration, but the interior is very beautiful. This is probably one of the finest example of the Mudejar style in Spain. Harmonious in proportion (approximately 76 x 30 feet high) it has an ornate coffered larch-wood ceiling. The women’s gallery has its own entrance and is well lit by five large windows. The synagogue is famed for its interior decoration. The wall with the niche made for the Sepher Torah is covered with panels and a plaster frieze sculpted in the oriental tradition. Numerous inscriptions along the wall commemorate Samuel Levi and Pedro I. Verses from the Psalms complete this decoration lit by windows with fine ornamental columns and lace-like mashrabiyahs.

In the outbuildings the museum exhibits gifts and articles collected from all over Spain, taking visitors through the history of Spanish Judaism. There are some very fine tombstones from León, and the oldest object os the sarcophagus of a child with inscriptions in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin and decorated with royal peacocks, a tree of life, a shofar, and a menorah. Seminars, courses, and talks are organized throughout the year on themes relating to Spanish Judaism. The synagogue is not used for worship.

Santa María la Blanca

The second synagogue, Santa María la Blanca , now bears its later name as a Christian church. Built in the early thirteenth century, it was consecrated as a church in 1411 by the preacher San Vicente Ferrer, the man behind the wave of conversions in 1391.

From 1600 to 1791, it was an oratory, and after that a barracks. It was restored in 1851 and declared a national monument. It is in the Mudejar style, but less rich than the Tránsito. Its twenty-five horseshoe arches and thirty-two columns create an impression of considerable space. Note the variety and quality of the capitals and the building’s similarity to Andalusian mosques.

Be sure to see the many streets of the old judería around the Calle Santo Tomé. In spite of much rebuilding, the area still has a certain charm.

The “Holy Innocent Child”

Jews in the two small villages of Tembleque and La Guardia near Toledo were accused of the ritual murder of a child, who immediately became a figure of popular legend under the name of the “Holy Innocent Child”. The accused were dragged before the Inquisition at Ávila in 1490 and 1491 and condemned. This stiry had such an impact that during the golden age, the great Spanish playwright Lope de Vega wrote the tragedy The Holy Innocent Child and Bayeu, Goya’s grandfather, painted a picture on the theme (it still hangs in the Toledo cathedral). Popular fervor bore fruit in the construction of a chapel on the road to Madrid, which still stands. Of course, historians have since shown that the accusation, although frequently repeated, was unfounded.

Suggested itineraries in the medieval Jewish quarter

In his book The Médieval Jewish Quarter of Toledo, which we recommend reading to anyone interested in the Jewish heritage of the city, Jean Passini offers three routes of visits to the city. Each of them will take you about an hour. If the majority of buildings are destroyed, you will however find some remains, and grasp the atmosphere that was once one of the most flourishing Jewish neighborhoods in southern Europe.

Route I: The borders of the medieval Jewish quarter

The tour starts at Plaza del Salvador, where the “Fernando Garbal jewish store and wine cellar” was located in 1491. The building is located at the foot of San Salvador Church. Then walk to Plaza de Marrón, where the Caleros Synagogue was located in the 15th century. Then take the streets Alfonso XII, San Pedro Mártir, Traversia San Clemente. You will arrive at Plaza de la Cruz, where was the north gate of the Jewish quarter. The house at number 1 of the place belonged to Master Alfonso, a pharmacist. Beyond the street Doncellas, there is a cellar with an octagonal dome, typical of medieval Jewish buildings. It can be visited by appointment. At number 11 Doncellas Street was a baking oven. Take Cuesta Street from Santa Leocadia and Calle San Martin to Callejón (Square) San Martin. On your left you will see houses built against what was the wall of the Jewish Quarter in 1637. At number 11 Calle Alamillos de San Martin, you will find the only surviving wall of what was a medieval tavern. At the end of Molino del Degolladero street, you will also find remains of the wall. On your right, take Bajada de Santa Anna where there was a medieval Jewish castle. Then you go past the old synagogue before ending up at your starting point, Plaza del Salvador.

Route II: The main Jewish district

From Plaza del Salvador, head towards Calle Taler del Moro to reach Paseo de San Cristóbal. Retrace your steps towards Plaza del Conde, then towards the Greek Museum. This museum is housed in what was Samuel Levi’s house. Two cellars are kept in the basement. There was also a courtyard and two rooms. You will then arrive at the synagogue of Tránsito, then at the old ritual butchery. Then take Bajada de Santa Anna, San Juan de los Reyes Bajada, Calle de los Reyes Católicos where the Sofer synagogue was located from the 12th to the 14th century. Turning left Calle del Ángel, you will pass under small arches that marked the entrance to the Alacava. Going down the stairs to Calle Santa Maria la Blanca, you will pass the synagogue of the same name. Continue to Traversía de la Judería. At number 4 you will find the Casa del Judío, the Jewish house, where you can visit the courtyard. Take Calle de San Juan de Dios, originally the main street of the Jewish Quarter. You will arrive at Calle, then Plaza de Santo Tomé, where there was the market, shops and stalls.

Route III: El Alacava

Start at Plaza del Salvador, then Calle Alfonso XII, Valdecaleros Plaza, Calle de las Bulas, Callejón de los Golondrinos. At numbers 29, 31 and 33 of this street were a synagogue and adjoining community buildings. From Plaza Virgen de Gracia, then Calle del Ángel, Arquillo de la Judería, then Callejón de los Jacintos, Calle Reyes Católicos, Plaza de Barrio Nuevo, Calle de Samuel Levi, Calle de San Juan de Dios, Plaza, then Calle from Santo Tomé.

Source (itinéraires) : Jean Passini, The Medieval Jewish Quarter of Toledo, Editions of Sofer

Interview with Carmen Alvarez, Director of the Museo Sefardi

Jguideeurope: Can you present us some of the objects shown at the museum?

Carmen Alvarez: The main masterpiece of our collection is the Samuel Levi synagogue: its artistic program, which is composed of a very rich group of plaster works and andalusian Moorish style wooden ceiling, is unique because of its style, both in Europe and in the Mediterranean area. It was one of the synagogues of the Jewish Quarter of Toledo and one of the proudest buildings owned by the Jewish Community in Medieval Castile.

The synagogue was built in mudejar style, that mixes Christian and Arabic decoration in this Jewish space. In this sense, the plaster works and the Hebrew and Arabic inscriptions of the building, together with the Andalusian influence, have become one of the best material examples of the coexistence between Jewish, Christian and Muslim religions in Toledo during the medieval period.

This epigraphy message, distributed along the building, is not only useful to recuperate the original cultural context but also extremely symbolic at the same time. In addition, it gives us an important message of the Jewish history in Spain. The founder, Samuel Levi Abulafia, was the main treasurer of king Pedro I of Castile, as well as the Court ambassador. But his life tragically evolved, as it occurred with the total of the Jewish community during the Catholic Period Kingdom until the official Expulsion in 1492 and the consequent Inquisitorial process, giving place to the complex phenomenon of blood purity. Toledo was one of the most visible examples in terms of converts groups and their cultural evolution: in Toledan archives, the history of many Jewish families who suffered this consequence is preserved.

The Samuel Levi synagogue was built between 1350-1360 as we can appreciate in the foundational inscriptions. The synagogue and midrash complex was actively used not only by the family but also as a community space in Toledo during the 14th century. For all these reasons, the building is mainly considered our core masterpiece giving origin to the Sephardic Museum of Toledo.

The National Sephardic Museum of Toledo was created as a consequence inside the ancient synagogue and it is considered one of the most important parts of the Jewish Legacy in Spain. The synagogue’s historical evolution is the main reason for its preservation. The Great Prayer Hall and the old Women Gallery are, by themselves, architectural treasures whose protection should be guaranteed. Attached to these spaces, we exhibit the major part of our collection, based on more than 2.400 pieces. The core exhibition is located around the historical building and in the ancient 16th century archive halls.

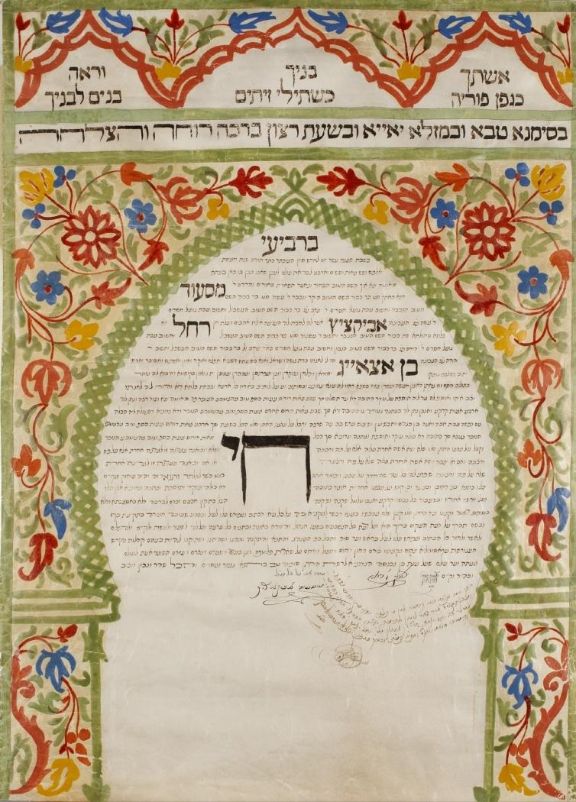

The permanent collection of the Sephardic Museum is mainly composed of archeological and ethnographical pieces. On one hand, we have antiquities that illustrate the history of the Jewish community in Spain, as the exceptional trilingual basin of Tarragona from 5th century that is, by the way, the inspiration of our corporate identity. On the other hand, we show a group of objects related to religion, traditions, life cycle and festivals, for example pieces of judaica or berberisca dresses (splendid gown used by Sephardi brides in northern Morocco), that are aimed to show all the richness of the Sephardi culture.

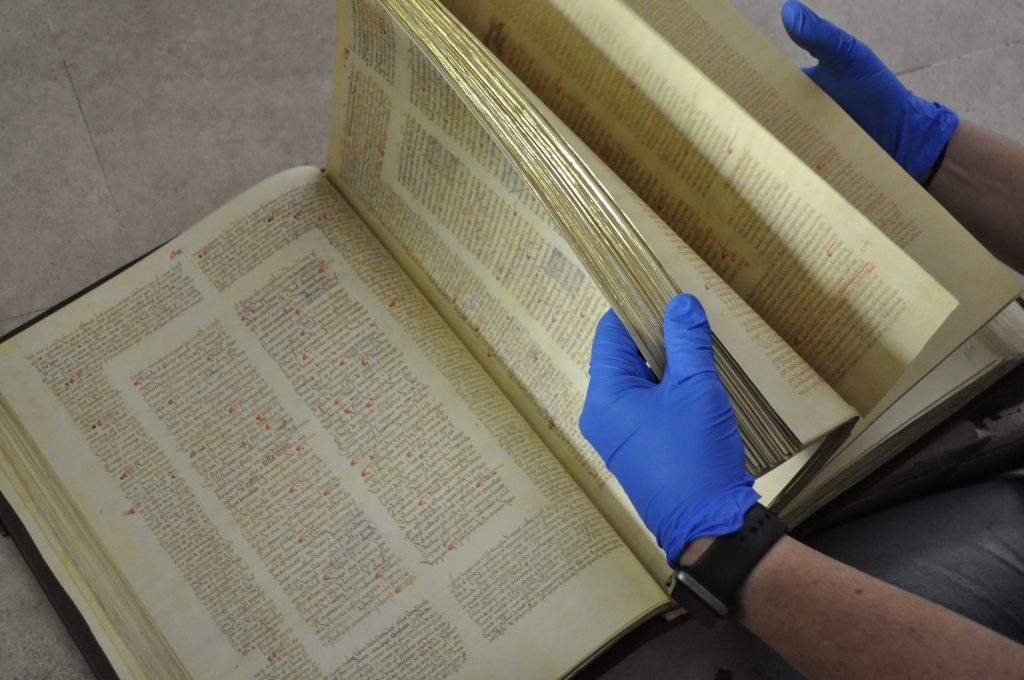

Moreover, it is highly remarkable for us our Old Bibliographic Collection, which is comprised of books, manuscripts and documents in Hebrew, Spanish, and Sephardic languages, spanning chronologically from the 14th century until 1950. Here you can find a link to more pictures and more information.

How do you perceive the evolution of interest in Sephardi heritage in Spain?

It is generally known that Sephardi heritage in Spain is trying to redefine its visibility through institutions and audiences. It has to do with its official network: we mean Spanish Jewish Community, University, CSIC (Scientific institution partly dedicated to the study of the Jewish culture and historical presence) and also cultural and tourism institutions. If all of us manage to coordinate and cooperate together, the main goal will be achieved. Science, communication and cultural programs could be better joined.

Nowadays we can find not a few important initiatives in Spain and Europe, as well, that are helping a lot in this task. And I don’t mean that the former institution’s efforts were useless, I mean that all these important bases are improving. From my point of view, we need to work more time together. Consequently, we will be programming and planning more exhibitions and cultural programs that could improve much more in terms of visibility of the Jewish culture in Spain. Since 1964 Sephardi Musem of Toledo aims to cooperate as much as possible, and we also work on that goal nowadays.

Can you tell us about a moving encounter at the museum with either visitors or exhibition participants?

There are a lot of good stories and amusing anecdotes at the Sephardic Museum, and many of them are contained in the visitor’s book of the Museum.

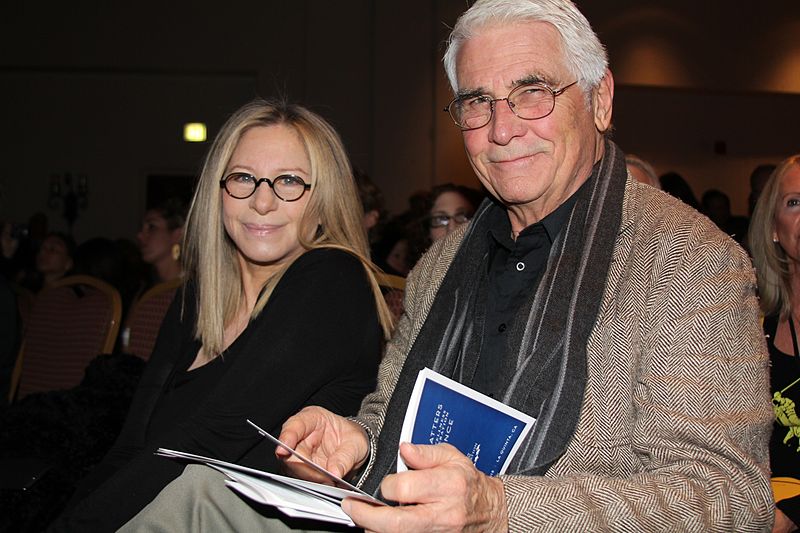

One of them is when Barbra Streisand visited us, at the beginning of my career here. I have fond memories of that day and I was pleasantly surprised that an internationally renowned artist was a close person and showed an interest in our collection. She told me that the pieces of the permanent collection are linked with her own life. For instance, she said that one of the ketubah of the exhibition was similar to that of her ketubah with James Brolin.

On the other, I still remember when Israel President, Ruben Rivlin, visited the Museum. He got excited when he signed at the visitor’s book because his signature was next to the Yitzhak Rabin signature. In saying this, I want to point out that the powerful emotions were feeling by all kind of people here in this Museum. This is the meaning of the Sephardic Museum.

But certainly, I want to tell you a magic anecdote linked with the previous director of the Museum, Santiago Palomero. Several years ago, Palomero found a special sign at the visitor’s book. It was a sketch of Corto Maltés, one of the most famous maverick and adventurer characters of the comic world by Hugo Pratt.

Palomero remembered that a mysterious and private man had visited the Museum some days ago and he resembled Hugo Pratt. Nowadays we consider this sketch as an artistic piece of the collection.

As you can see with such a surprising encounter, Jewish culture is still alive at the Sephardic Museum.

In the film A Monkey in Winter, Jean Gabin and Jean-Paul Belmondo debate whether the Prado is a museum surrounded by a garden or a garden on which a museum is placed. What is certain is that the place and the city that hosts it inspire Belmondo throughout the film.

And has inspired generations of conquerors, artists and authors for millennia, as evidenced by the great cultural and architectural wealth of the Spanish capital. Madrid will charm you with its diverse sources of beauty and inspiration between the Royal Palace and the Prado and well around and beyond.

We know that from the tenth century onward there was a small Jewish community in Muslim-ruled Madrid. This grew considerably after the reconquest.

Though hit hard by the pogroms of 1391, it was slowly built up again. It is also known that Jewish doctors such as Rabbi Jacob were, under the king’s protections, allowed to live outside the Jewish quarter, the better to tend to the sick.

In 1492 the Jews of Madrid left for Fès (Morocco) and Tlemcen (Algeria). The city’s six Jewish doctors went with them, leaving it without medical assistance. However, they resumed their position in 1493 after converting to Christianity.

Thanks to research by Madrid historians, it is possible to locate the city’s two Jewish quarters with considerable precision, although sadly few tangible traces remain. They formed around the Plaza Isabella (Calle Independencia and Vergara) and the Almudena cathedral, near the old Alcázar in the Cuesta de la Vega.

The Jews came back to Madrid only in the 1850s, sporadically and in an unorganized way. These were shopkeepers and bankers who, among other activities, were involved in the creation of the railroads. The best known of these families were the Bauers, who represented the Rothschild Bank.

Since they did not have their own cemetery, they created a special section in the British cemetery in the first years of the twentieth century.

A monument inspired by ancient Egypt houses the remains of Gustave Bauer (1867-1916), Manolin Bauer (1898-1906), and Ida Luisa Bauer (1906-08). Another thirty tombs remind us of the existence and origins of this small community in the early twentieth century.

A community of several thousand formed here during the Second Republic but disappeared during the civil war. In 1964, work has begun on the synagogue in the Calle Balmes, which also houses the Community Center. It was opened in 1968. The prayer hall is decorated with copies of the Hebrew inscriptions in the Tránsito Synagogue in Toledo. The community has a mikvah, a kosher butcher, and a school.

Madrid is also the headquarters of the journal Sefarad , a publication of the CSIC (Higher Council of Scientific Investigation), which, since its foundation in 1941, has published most of the Spanish and international research of Sephardic Judaism.

In 2023, following the pogrom in Israel, Jewish community organisations voiced their concerns about the sharp rise in anti-Semitic acts to local and national authorities.

It was the clock-making industry that attracted Alsatian Jews to the Jura beginning in 1835. Among the great names in this industry was Achille Picard. From 1858 onwards, devout Jews met in a prayer room.

They opened their Moorish synagogue in 1884. Its most recent interior renovation, in 1995, stressed the contrast between sober walls and the twelve multicolored stained-glass windows featuring biblical subjects, the work of Israeli artist Robert Nechin.

The 1999 exterior renovation brought back four small domes shaped like bells that had been removed in 1956. The facades are light beige, discreetly decorated with red motifs on the friezes and around the windows. The synagogue was the victim of antisemitic attacks in 2021.

A section of the cemetery of Tanzmatten and later of Biel-Madretsch was given to the Jewish community by the town council.

While the Jewish population reached 500 people at the beginning of the 20th century (a good part of whom came from Eastern Europe), there were only 150 in the early 1990s.

The Jewish presence in Bern probably dates from the 6th century. Jews are mentioned in the legal texts. During the Middle Ages, as in many other cities in the region, the situation of the Jews varied between reception, persecution (which began in Bern in 1294) and expulsion, depending on the power in place. In the wave of great expulsions that took place between the end of the 14th and the end of the 15th century, the Bernese Jews were expelled in 1427.

In the fourteenth century, the Jewish ghetto extended into the federal government’s current site: the Inselgasse, seat of the Department of the Interior, was called the Judengasse; the Federal Palace took over the spot of the Jewish cemetery. The current Community Center and its Moorish synagogue are not far away, on the Kapellenstrasse.

An unusual feature of the Kornhausplatz is Ogre Fountain, which dates from 1544. For some, the statue of the ogre in the act of devouring children represents merely a carnival image. For others, it is a Middle Age representation of the Jew accused of killing Christian children. The ogre is waring a pointed yellow hat, identical to the one imposed on the Jews to make them easily distinguishable.

In 2017, the Museum of Fine Arts in Bern presented the exhibition “Degenerate, Confiscated and Sold Art”. Among the 200 works were paintings by Franz Marc, Otto Dix and Otto Mueller. They are part of a legacy of the collector Cornelius Gurlitt, who also gave the museum paintings by Cézanne, Delacroix and Munch that he had hidden in his Munich flat for decades. His father was commissioned by the Nazis to sell art stolen from Jews by the regime, art labelled “degenerate”. The recovery of the works by the families was at the heart of a long legal process. The works shown in the exhibition do not concern the stolen paintings.

Interview with Jacob Guzman, historian and active member of the Jewish community of Bern

Jguideeurope : What motivated your commitment to the development of Bern’s Jewish cultural heritage?

Jacob Guzman : This heritage is in danger of disappearing if we don’t take the trouble to make it known to the population. We need other media than history books.

How did the big exhibition about Albert Einstein work out?

The director of the history museum contacted the community in Bern to get some information about Jewish life in Bern at the time of Albert Einstein. We have given some ritual objects, a Torah, and a towel that belonged to Einstein on long-term loan.

Can you tell us about an encounter with a visitor or speaker at a cultural event that particularly impressed you?

One example among many: the meeting with the architect Ron Epstein who wrote a book on the architecture of synagogues in Switzerland. We had the privilege in Bern to have, for several years, a series of lectures on Jewish themes. These paid lectures were, although organized by a member of our community, open to everyone. This gave us the opportunity to have contact with many speakers and allowed the non-Jewish public to know some aspects of Jewish culture.

The Jewish presence in Zurich probably dates back to the 13th century. During the Middle Ages, as in many other cities in the region, the situation of the Jews varied between reception, persecution and expulsion, depending on the power in place. In the wave of major expulsions that took place between the end of the 14th and the end of the 15th century, the Jews of Zurich were expelled in 1436.

Zurich contains the headquarters of the Swiss Federation of Hebrew Communities , founded in 1904 and whose archives were recently entrusted to the Zurich Federal Polytechnic School for better preservation there.

The collection includes the documents from JUNA, the FSCI press office, the Union of Jewish Mutal Aid Societies, the Swiss Refugees Council, the Union of Jewish Students, and the Action Group for Jews in the Soviet Union, along with extensive private archives.

The former ghetto of the Brunnengasse was the site of a 1349 pogrom against the Jews, who were accused of having spread the plague.

A commemorative plaque was unveiled 650 years later at 4 Froschausgasse, where the former synagogue stood. The narrow, nameless alley that leads to the Neumarkt was renamed Synagogengasse. In 2020, the Jewish community numbers 2500 members.

Today, the Israelitische Cultusgemeinde Zurich (ICZ), founded in 1862, represents the most important Jewish community in Switzerland.

The ICZ’s synagogue, at the corner of the Löwenstrasse and Nuschelerstrasse, was built in 1884 in Moorish style; it features a beige and red-striped facade, two towers topped by domes, and traditional windows. Its community centre housed a kosher restaurant, which was closed in 2019. There is also a school, a library and a mikve.

In addition, three distinct Jewish communities inhabit the city, each centered upon its won synagogue: the Orthodox Israelitische Religionsgesellschaft ; the Reform Or Chadasch community; and finally, the sizable Hasidic community around the Agudas Achim Synagogue , which gives off a truly shtetl ambiance.

In 2024, violent anti-Semitic attacks took place in Zurich, including physical assaults and an attempt to burn down a synagogue.

In 2025, the Jewish population was estimated to be around 7,000. There are two kosher shops in the city, including The Shuk, located on Waffenplatzstrasse.

The Jewish presence in Basel probably dates from 1213. During the Middle Ages, as in many other cities in the region, the situation of the Jews varied between acceptance, persecution and expulsion, depending on the power in place. In the wave of major expulsions that took place between the end of the 14th and the end of the 15th century, the Basel Jews were expelled in 1397.

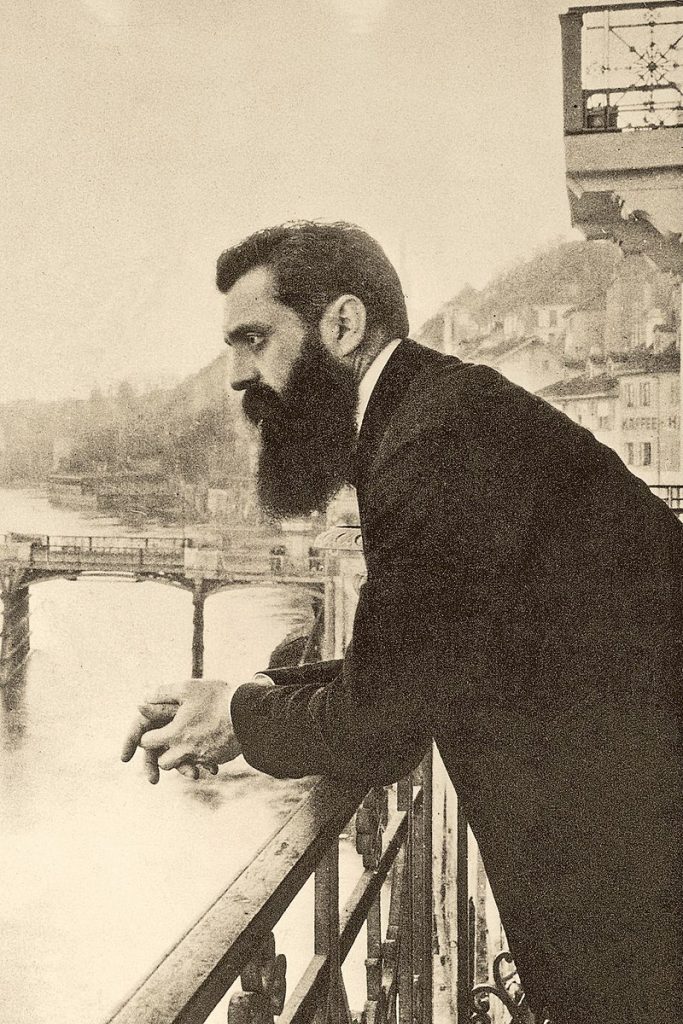

“In Basel, I created the Jewish State”, wrote Theodor Herzl in his diary after attending the First Zionist Congress, held from 29 to 30 August 1897. Nine more congresses would take place in Basel. A street in his name and a plaque in the casino serve as a reminder of the Zionist adventure’s origins in Basel.

First opened in 1868, the synagogue is the work of the architect Hermann Gauss, who took the one in Stuttgart, with its neo-Byzantine, Moorish, and Romanesque styles, as his model. It was enlarged twenty years later, and a second dome was added. During a further renovation in 1947, someone decided to cover the synagogue’s brightly colored walls in uniform gray. This gray corresponded better to the austerity of the era and local taste.

Forty years later, the colors of yesteryear resuscitated the refinished building. Modernizing the motifs had nonetheless dampened the eastern style. Inside, yellowish beige dominates, with blue and red decorations. A multitude of golden stars stand out against the dome. The polychromatic facades are red and white.

The only Jewish Museum in Switzerland (Jüdisches Museum der Schweiz) is found in Basel. Its collection reflects the region’s Jewish heritage and features books in Hebrew printed in Basel, gravestones, and documents on Jewish history and the Zionist congresses.

The Community Center houses as well the kosher restaurant Topas.

In 2012 the first synagogue in 83 years was opened. At that time, the Jewish community numbered almost 2000 members. It is part of the Chabad Feldinger Jewish Centre . It is located next to the Chabad Synagogue. It was vandalised in 2018. In the same year a kosher butcher shop was attacked several times.

Interview with Barbara Haene, Head of research and events at the Jewish Museum of Switzerland

Jguideeurope: What events are planned for the European Days of Jewish Culture?

Barbara Haene: The Jewish Museum of Switzerland has been in charge of the organization of the European Days of Jewish Culture in Switzerland since its initiation in 1999. We have all kind of activities. The city tour “In Herzl’s footsteps through Basel” and the guided tour of the synagogue are also very popular every year.

Can you introduce some of the objects in the “Jewish for beginners and experts” exhibition?

As a historian working on the Jewish history of Switzerland, I of course have certain preferences. I particularly like objects that bear witness to the simple life of the Jews in the Endingen Lengnau countryside, for example, a Torah coat originally used for a woman’s dress.

Or a pocket watch from La Chaux-de-Fonds that testifies to the importance of Jews in the watchmaking industry in Switzerland. Of course, the first Zionist Congress, which celebrates its 125th anniversary this year, is also of great importance for Basel’s Jewish history. The Jewish Museum holds numerous objects relating to the first Zionist Congress. For example, a collotype showing the participants of the congress is worth seeing.

Have you noticed a change in public expectations in recent years?

Over the last few decades, the knowledge of young people has changed. They used to be relatively familiar with the biblical stories, especially the ones concerning Adam and Eve, Moses and the Ten Commandments, Rachel and Leah. They knew the Old Testament characters from church, from religion classes, or from their children’s Bibles. Today, secularization has greatly increased.

Few young people visit churches. Almost no one reads the Bible either. But today, those same young people know more about Jewish customs. They know about Hanukkah and Shabbat, about bar / batmitzva holidays, and about kosher regulations.

Diversity is in vogue. Young people encounter Jewish culture in school, on Netflix and Youtube, in pop music, and in food. Their knowledge of Judaism is marked by hummus, falafel and bagels, among other things.

Can you tell us about an encounter with a visitor or speaker at a cultural event that made a particular impression on you?

A few weeks ago, we welcomed Rabbi Bea Wyler to the museum. We have her prayer shawl, her talith, in our collection. Bea Wyler was the first woman to serve as a rabbi in German-speaking Europe after the Holocaust. When she was ordained in the 2000s, she was confronted with many opposing currents as a woman in an all-male profession.

Today, she is the first in a series of young female rabbis. Women are valued, enjoy a certain prestige, and are only experiencing headwinds in some Orthodox and ultra-Orthodox circles.

Until the end of the eighteenth century, the two villages of Endingen and Lengnau were the only ones that authorized the permanent establishment of Jews. Beginning in 1622, they resided here under the rubric of “protected foreigners”, and their communities were able to practice religion and conduct internal administrative affairs in total independence. A document from this year attests to their presence.

In 1750, the two communities purchased a plot of land midway between the towns for a cemetery . Before this, Jews were obliged to bury their dead beyond the Rhine on an island which was later purchased by the town of Waldshut. The Jewish cemetery has 2700 graves.

The first synagogues date from 1750 for Lengnau and 1764 for Endingen . They were renovated in 1848 and 1852 respectively. They appear in a book by Johann Caspar Ulrich published in 1768.

They resemble churches, with a clock on their pediments and steeples, elements required by the authorities. In 1850, there were 1515 Jews present in these two cities. These Jews came mainly from the towns of Haute-Alsace (Buschwiller, Hegenheim, Hagenthal…), the Baden region (Randegg, Wangen, Gailingen, Worblingen…) and Hohenems. Those cities were close to Switzerland, with which the general population had economic and cultural ties.

The permits granted to migrate to the other municipalities caused a constant fall in this number. The wave of emancipation of the Swiss Jews took place throughout the 19th century, depending on the municipality.

In Endingen, a churchless village, it was the synagogue on the central square that struck the hours. The building was ultimately renovated in 1998.

The town’s policy of tolerance must not overshadow the discrimination that was still current around 1910: all houses had two front doors, one reserved for Christians and the other for Jews. There are many houses that bear witness to this period. Unlike most of the Jewish ghettos in Europe, the traces of Jewish life are still very present in these villages. Among the personalities from these villages is William Wyler, the director of Ben Hur and Funny Girl.

Since 2009, a Jewish cultural tour is presented by the local authorities to pay tribute to the historical heritage of the villages. Visitors can walk between synagogues, cemeteries, double-entrance houses, as well as an old mikve and shops.

In 2018, there were only about 20 Jews left in Lengnau and Endingen. Most of them were elderly people living in a retirement home.

Founded in 1833, the Jewish community of La Chaux-de-Fonds met in a flat on rue Jaquet-Droz. Then, in 1853, a private house was used as a synagogue. From 1872, a Jewish cemetery was used in the commune of Les Eplatures.

La Chaux-de-Fonds’s Jewish community opened its first synagogue in 1896. Architect Kuder was inspired by the synagogue in Strasbourg, which was later destroyed by the Nazis. In Romanesque style and constructed in freestone, the building contains a 105-foot-high octagonal dome with twenty-four windows and is covered in polychromatic tiles. The facade includes the tablets of the Law and two turrets. Inside, the central dome and four smaller domes at each corner are multicolored, in harmony with the stained-glass windows. The principal motif is a Star of David, from which rays extend that bear the names of biblical characters upon a starry sky.

In 1900, La Chaux-de-Fonds was the fourth Swiss town with the most Jewish inhabitants, after Zurich, Basel and Geneva. Some of the great names in the watchmaking industry lived there. Other professions practiced by the Jews of La Chaux-de-Fonds include crafts, antiques, and teaching. They also played an important role in the arts and culture, as well as in the world of sport.

In the second half of the 20th century, the Jewish population fell. At the turn of the millennium, there were 70 Jews.

The Jewish presence in Lausanne is attested continuously from 1848 onwards, when several families met in a rented room. In 1895, the community had 41 members. In 1909, there were 110 members. It should be noted that the vast majority of Jews did not participate in community life. In 1909, there were 989 people of the Jewish faith in Lausanne. Kosher meat was imported from Evian because of the laws on slaughter.

An oratory was inaugurated in the ruelle du Grand-Pont in 1878. A prayer room was used from 1884 on rue du Petit-Saint-Jean. In 1898, a synagogue was built in rue du Grand-Chêne. In this impetus, Lausanne’s synagogue , was built in 1910 in a fairly remote neighborhood at the time. It can be found today right near the train station in the heart of the city.

Its Romano-Byzantine style is reminiscent of the synagogue located on rue Buffault in Paris: Tablets of the Law dominate its facade, which contains a rose window shaped like a Star of David; it also features semicircular window arches, Romanesque apses, and two towers. The interior is Neo-Byzantine. The Community Center is adorned with stained-glass windows by Jean Prahin.

There are two cemeteries that are used by the Jews of Lausanne: Cery , Prilly and another one further in Vassin . The one in Prilly dates from the beginning of the 20th century, when the cemetery used until then in Montoie reached saturation. The graves in Montoie were transferred to Prilly in 1950. A second cemetery was created in Prilly in 2002.

Jewish life in Lausanne experienced a boom from the 1970s onward, particularly thanks to the arrival of Sephardic Jews. Religious services became more regular, and a school group was created. In 1975, the first Bulletin of the Jewish Community of Lausanne was published.

In 2010, the 100th anniversary of the Lausanne synagogue was celebrated.

Before Jews were able to settle in Geneva, the neighboring city of Carouge (at the time part of the Kingdom of Sardinia) opened its doors to them around 1779. The sole remaining Jewish vestige is the old cemetery, which was restored in 1996.

A great spirit of religious tolerance allowed this arrival at the time, while in Geneva the Jews had been expelled since 1490. The acceptance of Geneva’s Jews was only concretely achieved at the end of the 19th century, in 1874 to be precise, the date of emancipation at the federal level.

The new cemetery, in the Franco-Swiss border town of Veyrier, contains the graves of numerous luminaries, such as the writer Albert Cohen.

The city of banking and watchmaking… but not only. Geneva is a much more complex city, home to a great university and eminent thinkers for centuries, and it even published one of the first two comic strips in history.

It seems that the Jewish presence in Geneva dates from the 13th century, mainly around the Place du Grand-Mézel in the old town. The Jews were expelled from the city in 1490 and forbidden to stay there until the 19th century.

The Grand-Mézel was the oldest closed Jewish quarter in Europe, established in 1428 (88 years before the Venice ghetto). The old town is situated on a small hill, with the shopping streets on one side and the university and cultural buildings on the other. Coming down from the Grand-Mézel, 200m away you will find the historic synagogue of Geneva.

Reestablished in 1852 by Alsatian Jews, the Jewish community of Geneva was offered a plot of land by the city to build a synagogue as a sign of tolerance toward non-Protestant minorities.

Located at the Place de la Synagogue and combining eastern style with Polish characteristics, the Beth Yaacov Synagogue was returned to its original colors in 1997: designed in 1857 by Jean-Henri Bachofen, it features a gray and pink-striped facade, four crenellated turrets crowned by domes, and a central dome topped with the Tablets of the Law. The interior (arches and dome) is predominantly light blue, while the stained-glass windows and paneling add to the vividness of the colors.

The University of Geneva was established by Jean Calvin in 1559. The urgent need to fill lecture halls in the 19th century unexpectedly benefited from the political upheavals in Eastern Europe. The very reactionary period of the Russian Empire forced many students to leave the country and find places at Western universities. This was especially motivating for women, who found free access to Geneva universities, a rare event at the time. Thus, Jews from the East, often from very modest conditions, made up more than half of the students in Geneva. Among them, Lina Stern, a world specialist in the brain and the first woman professor at the University of Geneva. But also Chaïm Weizmann, the future first president of Israel, who taught chemistry there and founded a publishing house. There he developed with other students the idea of what would become the Hebrew University of Jerusalem. As well as many Zionist, communist and Bundist figures.

In the spirit of reconciling studies and manual labour, Aron Syngalowski established in 1943 in Geneva the provisional headquarters of the ORT (Organisation – Reconstruction – Labour), founded in 1880 in Russia to help needy Jews. This world headquarters remained in Switzerland until 1980.

The Heikhal Haness Synagogue , serving the Sephardic Jewish community, was built in 1970. This marble construction was needed in answer to changes in Geneva’s community, as Mediterranean Jews have now become the majority.

The Liberal Jewish Community of Geneva – GIL created by Rabbi François Garaï in 1970, gathers today about a third of Geneva’s Jews. It was the first synagogue in the French speaking world to enable girls to read the Torah during their bat-mitsvah.

City known over the world for its diplomatic summits, Geneva inspired many writers, among them Romain Gary and Albert Cohen, diplomats themselves. A wonderful tribute to the city is shared in Albert Cohen’s novel Mangeclous when the Solal cousins stroll around the sights and parks and turn the UN upside down.

Albert Cohen arrives in Geneva to pursue his studies. He became a Swiss citizen and was admitted to the Geneva bar. Following his elaboration of the passport for displaced persons, he will return to the city in 1947 to head the Protection Division of the IRO. Geneva will be the city where Cohen’s work confronts generations and discomforts between them. First of all, between him and his mother, who, like his character Solal, is ashamed of her origins and the characters who represent her too “loudly”. He will cry for these moments of shame in The Book of My Mother and will mock his own attitude in Mangeclous, the main character of this novel and who bears the same name causing a great commotion in the city and the highest UN authorities, by setting himself up as an emissary of the creation of the State of Israel.

The Community Center houses the Jewish main library, rich in several high quality scientific and artistic collections, as well as the Jardin Rose (Rose Garden) and a kosher restaurant. The Jewish Community Center also organizes many cultural events.

The Jewish population in 1900 consisted of 1100 people. In 2024, estimates suggest that there will be 6000.

Here’s our interview with Rabbi Éric Ackermann, during our visit to the beautiful and ancient Beth-Yaacov Synagogue.

Jguideeurope: How long have you been rabbi of the Beth Yaacov Synagogue?

Éric Ackermann: I’m not the rabbi of the synagogue; I’m a rabbi at the synagogue. In fact, there are several rabbis in Geneva, and I joined the Beth-Yaacov team, the oldest of whom, Rabbi Jacob Tolédano, is the mainstay of the synagogue. Rabbi and cantor for over 50 years, he delights the faithful with one of the most beautiful voices in Europe. That said, I’ve been in this synagogue for almost 20 years.

Given its age and its important place in Geneva Judaism, have you noticed a growing desire on the part of new generations to continue the celebrations here?

It’s the oldest Geneva synagogue still standing, dating from before the emancipation of the Jews. Today, an ever-growing number of worshippers want to perpetuate their family celebrations here, from circumcision to weddings and other anniversaries and ceremonies.

What religious and cultural activities does the synagogue organise?

As I mentioned earlier, the synagogue’s religious life is marked by numerous CIG ceremonies, as well as interfaith meetings, training courses and visits to Geneva schools. On the cultural front, there are numerous courses, debates and conferences. There’s no shortage of community festivals and events. Don’t hesitate to visit the community website: comisra.ch

You are very involved in Jewish-Christian dialogue. How do you see it developing in Switzerland?

I think that since the Second Vatican Council, trust and respect have been established, and dialogue has been able to strengthen and flourish. In fact, in 2018 I was awarded the Swiss Dialogue Prize by the FSCI for my work with the Geneva Interfaith Platform, of which I was president for 7 years. Its development contributes to ‘living together’ and therefore remains generous. In short, dialogue with other communities is an exercise in the times in which we live.

The history of the Jews in Speyer dates back more than 1,000 years. In the Middle Ages, the city of Speyer (formerly Spira) was home to one of the largest Jewish communities in the Holy Roman Empire. Its importance is attested to by the frequency of the Ashkenazi Jewish surname Shapiro/Shapira and its variants Szpira/Spiro/Speyer. The community was completely wiped out in 1940 during the Holocaust. With the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, Jews resettled in Speyer and a first minyan was held in 1996.

A rich history

The first evidence of a Jewish community in Speyer dates back to the 1070s. It came from the famous Kalonymos family of Mainz, who had emigrated from Italy a century earlier. Other Jews from Mainz may also have settled in Speyer at the same time.

The history of the Speyer community began in 1084, when Jews fleeing pogroms in Mainz and Worms took refuge with their relatives in Speyer. They were certainly encouraged to do so by Bishop Rüdiger Huzmann (1073-1090), who allowed a large number of Jews to live in his city with the consent of Emperor Henry IV. In his charter (Freiheitsbrief) for the Jews, the bishop approved the establishment of the community in a defined area.

This area corresponds to the former suburb of Altspeyer in the area east of today’s railway station. This fortified quarter was located to the north, outside the city walls, and was the city’s first documented ghetto.

The charter ratified by Bishop Huzmann went far beyond the practice elsewhere in the empire. The Jews of Speyer were allowed to engage in all kinds of trade, exchange gold and silver, own land, have their own laws, judicial and administrative systems, employ non-Jews as servants, and were not required to pay customs duties at the city limits.

The two charters

The reason why Jews were called to Speyer by the bishop was their important role in fiduciary and commercial trade, and in particular their links with distant regions. Large-scale financiers were needed for the construction of the cathedral. A special feature of Speyer is that the rights and privileges specially granted to the Jews of this city were eventually extended to all Jews in the empire.

The two charters of 1084 and 1090 marked the beginning of the ‘golden age’ of the Jews in Speyer, which, with restrictions, was to last until the 13th or 14th century. According to these documents, an “Archisynagogos”, also called ‘Jewish bishop’, presided over the administration and the community court. He was elected by the community and ‘knighted’ by the bishop. Later sources mention a ‘Jewish council’ of twelve members, presided over by the ‘Jewish bishop’, who represented the community outside. In 1333 and 1344, the authority of the Jewish council was ratified by the municipal council of Speyer.

In 1096, the Jews of Speyer were among the first to be affected by the pogroms caused by the plague epidemic, but compared to the communities of Worms and Mainz, which followed a few days later, they were relatively spared.

Development of Jewish life

Around this time, a second Jewish quarter was established near the cathedral, along Kleine Pfaffengasse, which was formerly Judengasse (Jewish Street), while the old Jewish quarter and its synagogue remained in Altspeyer. It is estimated that the Jewish community in Speyer at that time consisted of 300 to 400 people.

During these years, the Jewish community in Speyer became one of the largest in the Holy Roman Empire. It was an important centre for Torah study and, despite pogroms, persecution and expulsions, had a considerable influence on the general spiritual and cultural life of the city. At a synod of rabbis in Troyes around 1150, the leadership of the German Jewish community was transferred to the communities of Speyer, Worms and Mainz.

Intellectual and religious development

The three communities formed a federation called ‘ShUM’ (שום: initials of the Hebrew names of the three cities) and retained this power until the middle of the 13th century. The SHUM cities had their own rites and were recognised as a central authority in legal and religious matters. Speyer had renowned Jewish schools and a well-attended yeshiva.

Due to the high esteem in which the three ShUM cities were held in the Middle Ages, they were praised as a ‘Rhenish Jerusalem’. These cities had a considerable influence on the development of European Ashkenazi culture. In the 13th century, Isaac ben Moses Or Sarua of Vienna wrote: ‘From our teachers in Mainz, Worms and Speyer, the teachings have spread to all of Israel …’.

However, even during this flourishing period, anti-Semitic violence broke out in 1146, 1195, 1282 and 1343. In 1349, during the Black Death, the Jewish community of Speyer was completely wiped out. In the years that followed, a small community re-established itself, but never regained the size and status it had before 1349. The Jews were expelled from Speyer from 1405 to 1421, then ‘for eternity’ in 1435. One of the refugees from Speyer was Moses Mentzlav, whose son, Israel Nathan, founded the famous Hebrew printing press in Soncino, Italy.

Return of the Jews to Speyer

From 1621 to 1688, Jews resettled in Speyer. It was mainly during the Thirty Years’ War and the years that followed that the indebted towns called on the financial power of the community. The city began borrowing money from Jews as early as 1629. However, following complaints, trade and financial transactions with Jews were completely banned before Speyer was burned down by the French in 1689. During the subsequent years of reconstruction, Jews were not allowed to resettle permanently.

A Jewish community established itself in Speyer after the French Revolution. It was distinguished by its liberal and emancipated attitudes, which repeatedly brought it into conflict with the more conservative Jewish communities in the Rhine region. In 1828, the community founded a charitable organisation and contributed to the city council’s efforts to combat extreme poverty in the city. In 1830, the Jewish community in Speyer had 209 members. In 1837, a new synagogue was built on the site of the former St. James Church on Heydenreichstraße; the synagogue included a small school.

Rise of anti-Semitism

In 1890, the Jewish community had 535 members, the largest number ever recorded in Speyer; by 1910, their number had fallen to 403. In the early 1930s, Jews in Speyer began to leave for larger cities or emigrate due to rising anti-Semitism.

By 1933, the number of Jews in Speyer had fallen to 269, and by the time their synagogue was burned down during Kristallnacht, only 81 remained. On the night of 9 November, SA and SS troops ransacked the synagogue on Heydenreichstraße, carrying off the library, valuable fabrics, carpets and ritual utensils, and set fire to the building. Along with the synagogue, the Jews also lost their school. That same night, the Jewish cemetery was vandalised. A member of the community set up a prayer room in his house on Herdstraße. The city then used this house as a storage place for furniture stolen from deported Jews.

On 22 October 1940, 51 of the 60 Jews remaining in Speyer were deported to the Gurs internment camp in southern France.

Some of them managed to flee to Switzerland, the United States and South Africa with the help of the local population, while the others were deported to Auschwitz. Hidden in Speyer, only one Jew survived the Nazi era.

In the 1990s, it was decided to build a new synagogue as an extension of the former medieval church of St. Guido. The Beith Shalom Synagogue was consecrated on 9 November 2011. It also houses a community centre.

The medieval Jewish cemetery of Speyer lay opposite the Judenturm (Jews’ tower) to the west of the former Jews’ quarter in Altspeyer (today between Bahnhofstraße and Wormer Landstraße).

After Jews resettled in Speyer in the 19th century, a new cemetery was built at St. Klara Klosterweg and remained in use until 1888. The former mortuary and a part of the western wall are still in place. In 1888, the Jewish cemetery was moved to the new city cemetery built in the north of Speyer along Wormser Landstraße, where it now occupies the southeastern section.

How to get there

When you leave Speyer railway station on Banhoferstrasse, you will find yourself in Adenauer Park. Named in honour of former German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, it is the site of the grave of another former chancellor, Helmut Kohl.

After crossing this pretty little park, you will come to St.-Guido-Stiffts Platz. Don’t be surprised to find a sign in two languages, German on one side and Hebrew on the other, indicating the location of the Kikar Yavne . This square is named in honour of the Israeli city of Yavne, with which Speyer has been twinned since 1998.

Take the small alleyway called Weidenberg and you will come to a pretty little park full of flowers, where you will see a metal menorah sculpture and, just behind it, Speyer’s Beit Shalom synagogue .

Next, walk down Wormser Strasse and the adjacent narrow streets with their colourful houses and lush vegetation to reach the heart of the old town. Stolpersteine have been placed opposite number 9 on the street.

At the end of this street is the unmissable Maximilian Strasse. On the right, you can see one of the city’s most famous monuments, the Altpörtel, a 55-metre-high medieval gate built in the 13th century.

Maximilian Strasse is the main shopping street in the old town. It connects the main ancient monuments from the Altpörtel to Speyer Cathedral. Opposite the beginning of Wormser Strasse, 50 metres from the Altpörtel, is the Galeria Speyer, a large department store located on the site of the synagogue destroyed during Kristallnacht .

If you take the Karlsgasse alleyway that runs alongside the store, you will find the Memorial erected in 1992 in honour of the Jews of Speyer who were deported during the Holocaust.

Then turn left onto Hellergasse, which continues into Kutschergasse, and you will arrive at the small market square. Crossing it diagonally, you will come to Kleine Pfaffengasse , where the Jewish Museum of Speyer, the SchPIRA and its mikveh , is located.

Just before the museum, on your right, you will see Judengasse and Judenbadgasse, named after the Jewish alley and the Jewish ritual bath, respectively.

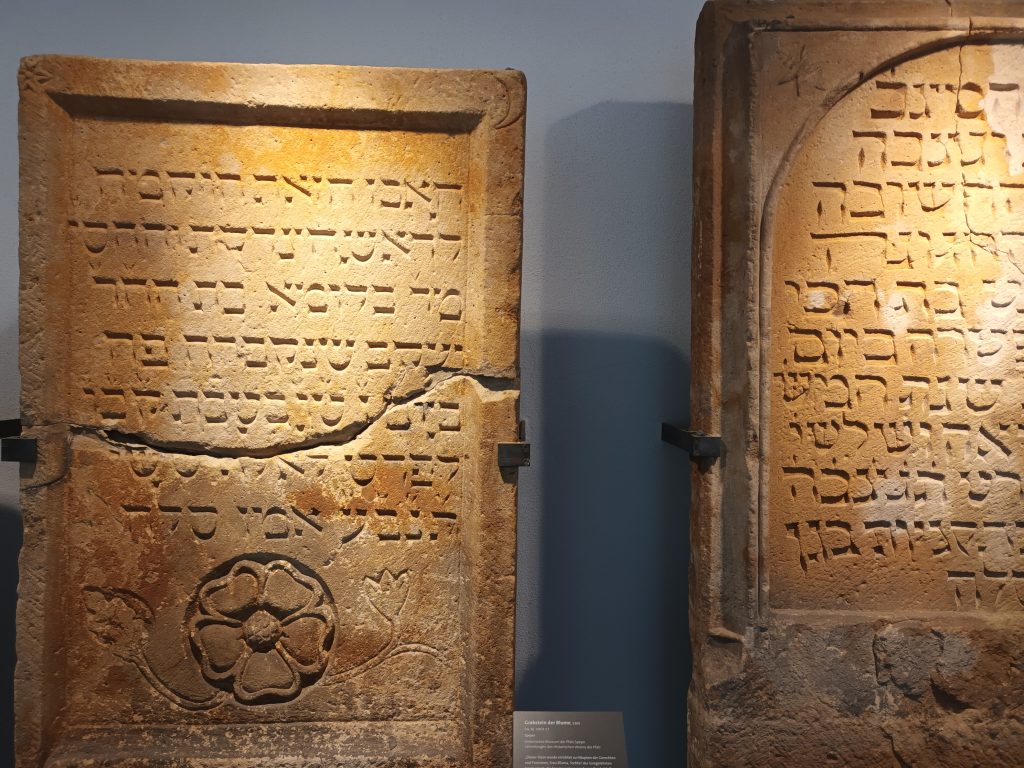

The SchPIRA is relatively small. It contains a few ancient objects, remnants of the old synagogue and gravestones, which appear to date from the 13th century.

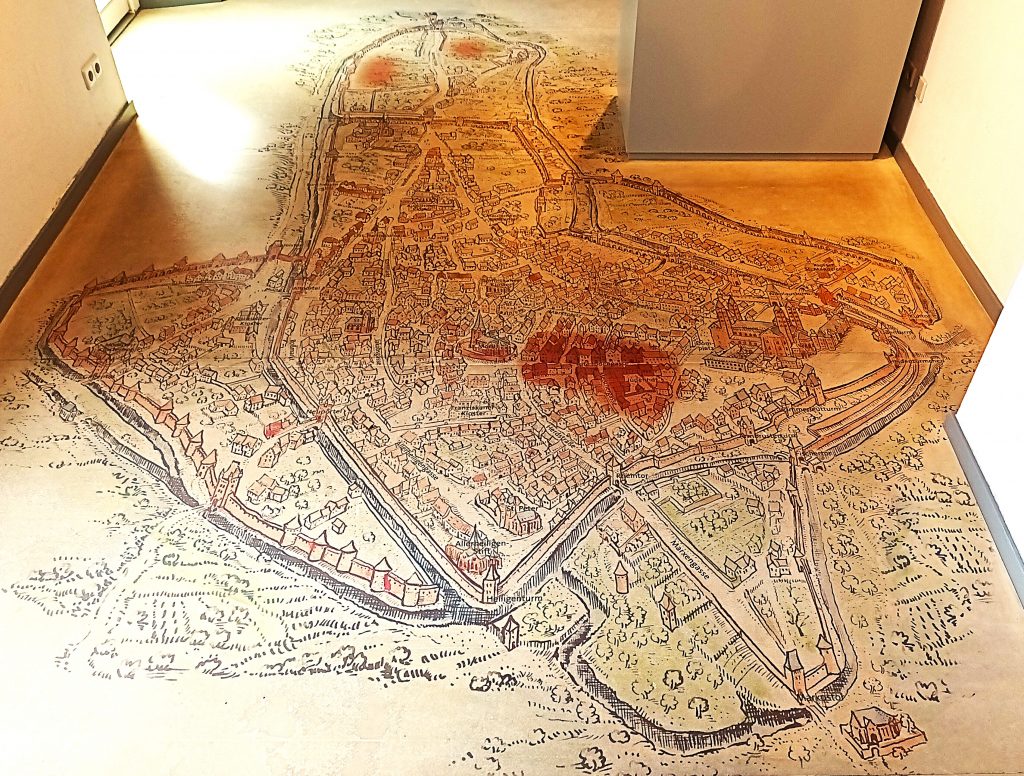

A model of the old mikveh is on display so that visitors can see what it looked like as a whole. On the floor is a map of ancient Speyer.

In the next room, a few panels trace the history. Seats allow you to watch presentation videos in German or English at your leisure. Two films are available in English. The first lasts 12 minutes and tells the story of the synagogue, its evolution over time and the necessary (re)constructions. A particularly interesting element in this presentation is the construction of the women’s hall. In some synagogues at the time, women were not just seated behind or above the men, but had their own room. A few windows connected this room to the men’s room so that the women could follow the prayers.

The video shows the architectural evolution of the synagogue and the influential role played by this community at the end of the Middle Ages. It also mentions its destruction, following classic anti-Semitic accusations of poisoning wells, as was the case throughout medieval Europe. The other video is devoted to Jewish rituals, with a view to explaining their meaning to visitors.

In the museum’s small flower-filled garden, you will see a few sculptures, including one entitled ‘The Sages of Speyer’, in memory of all the eminent rabbis who trained and taught there.

Opposite the small inner garden, on the right, you can see the remains of the synagogue with its two rooms. Red and yellow stones bear witness to the architectural evolution of synagogues over time. Some windows connecting the men’s room to the women’s room are still intact. These windows, actually six small openings, were cut into the wall between the two rooms. There was also a connecting door between them, located at the western end of the wall. Benches were positioned around the women’s prayer room. One of them is still preserved today.

The synagogue, consecrated in 1104, was built as a Romanesque room approximately 10 metres wide and 17 metres long. The place of worship was damaged during the pogrom of 1349 and repaired in 1354 with several modifications to its construction. After the expulsion of the Jews in the early 16th century, the synagogue was converted into a municipal arsenal before finally being demolished.

The first architect to work on the synagogue was not Jewish, as Jews were prohibited from practising certain trades at that time, particularly those related to craftsmanship. In 2025, restoration work was carried out on this former synagogue.

Right next to the remains of the synagogue is the famous Speyer mikveh. The ritual bath fell into disuse in the 16th century, but its ruins are now the oldest visible remains of a mikveh in Central Europe. Today, this European archaeological heritage site has been made accessible to the public and the pool is still fed by groundwater. The first mention of the mikveh dates back to 1128. It was therefore probably built at the same time as the synagogue, at the beginning of the 12th century. It is very well preserved and lit, allowing you to descend to the place where the ritual bath was located, where water still flows abundantly.

The Speyer mikveh is considered today to be the best preserved in Europe. A barrel-vaulted staircase leads through a vestibule to a square well located 10 metres below ground level. The mikveh is decorated with rich colourful ornamentation from the Romanesque period. A two-part window opens up a view of the basin. The mikveh is now covered with a glass structure to protect it. The bath is no longer officially in use today, but its use can be arranged outside official opening hours for tourists.

All around are explanatory panels about the construction of the mikveh, as well as the chronology of Jewish life and the heyday of the Speyer community, and its contemporary revival.

Leaving the SchPIRA museum, turn right onto Kleine Pfaffengasse and continue for 100 metres to Domplatz, where you will find the beautiful and immense Speyer Cathedral, built from the 11th century onwards under Conrad II.

At the entrance, you can see famous scenes from the Bible carved in wrought iron. Inside, as in many German cathedrals, beautiful organs are sometimes played to the delight of visitors. Paintings and statues inside and outside the cathedral pay tribute to the Bible and German rulers.

To round off your walk, we recommend the lovely park just behind the cathedral, where you can see contemporary sculptures and enjoy the peaceful greenery.

As the cultural and municipal services proudly point out, Worms has long been a central city for many religious movements. Thus, within a small area in the heart of its old town, you will find the impressive cathedral, churches, as well as the municipal buildings and the old Jewish quarter with its museum and synagogue.

History

The Jewish presence in Worms dates back to the mid-10th century. They were mainly merchants and lived on what is now the Judengasse, meaning ‘Jewish street’.

Near the city walls, the first synagogue in Worms was built in 1034, thanks to a donation from Jacob and Rachel Ben David. This made it easier to welcome great European scholars, and Worms became, like the other cities of the SChum, famous for its yeshivot and illustrious students and teachers, including Rashi.

It was during this same period that the Jews obtained land at the other end of the city to establish a cemetery. Burials took place there uninterruptedly until 1911.

The mikveh probably dates from the end of the 12th century. Built by the community thanks to donations from a certain Joseph, it was dug 7 metres deep to reach the spring water. It included a room for changing and another for cleaning before immersing oneself in the mikveh water.

The synagogue had to be rebuilt following the destruction caused during the Crusades of 1096 and 1146. It was reopened in 1175. Meir and Judith bar Joel made a donation in 1212 to build a prayer room for women, adjacent to the men’s room. Built in the same spirit as in Speyer, the Frauenschul was connected to the men’s hall by a door and five small windows that allowed the women to hear the prayers. It was not until the 19th century that this space was opened up to allow women to participate more fully in the prayers.

During the persecutions of 1349, the year of the Black Death, more than 400 Jews were murdered, the Judengasse was destroyed, and their property was looted. The synagogue was rebuilt in Gothic style. From that moment on, the Jewish community of Worms suffered an irreparable decline, particularly in terms of intellectual and religious production.

At the end of the 14th century, just under 200 Jews lived on Judengasse. A few students joined them, and by 1500 the Jewish community numbered around 250.

Forced to live in the ghetto, the number of Jews nevertheless increased thanks to the support of Emperor Ferdinand I (1503-1564), who prevented the municipality from expelling them. Thus, from the end of the 16th century to the end of the 18th century, between 500 and 700 Jews lived on Judengasse. However, Louis XIV’s troops destroyed the city in 1689 during the War of the Palatinate Succession, including its Jewish quarter.

As in various other European cities conquered by French troops in the early nineteenth century, Jews were granted the same rights as their fellow citizens. With this equality finally achieved, Jews contributed greatly to the economic, intellectual and political development of Worms. Proof of this successful integration, Ferdinand Eberstadt (the son of a family established in Worms since the 17th century) was even mayor of Worms from 1849 to 1852.

The intellectual momentum of the 19th century also encouraged changes within the Jewish community. The Levi Synagogue was built in 1875, opposite the other synagogue, following rich but tense debates between traditionalists and liberals. It was named in honour of its founder, Leopold Levy.

The Jewish community in Worms had 1,000 members in 1933. On 3 June 1934, the synagogue celebrated its 900th anniversary, despite fears about the Nazi takeover.

During Kristallnacht on 9-10 November 1938, the old synagogue in Worms was destroyed once again. The Levy Synagogue was severely damaged that night and suffered further damage during an Allied bombing raid on the city in 1945. Only a few walls remained standing, to such an extent that in 1947 there was no option but to demolish it.

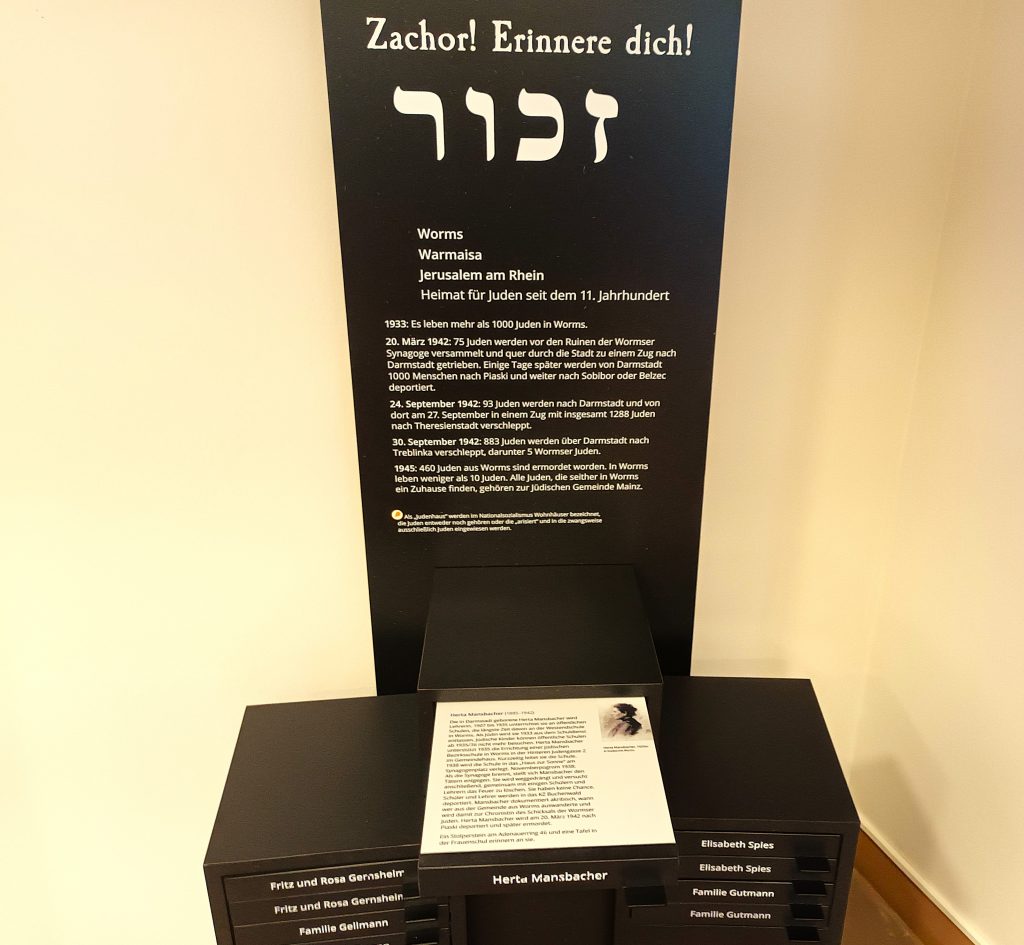

In March 1942, 75 Jews were rounded up and sent to Sobibor and Belzec. In September 1942, another 93 were sent to Theresienstadt and five to Treblinka. In total, 460 Jews from Worms were murdered during the Holocaust.

The synagogue was rebuilt between 1959 and 1961. The project was made possible thanks to the support of Jews who had managed to flee during the war, as well as the current communities of Mainz and Worms, the city of Worms, the state of Rhineland-Palatinate and the Federal Republic of Germany.

Behind this synagogue is a place of study known as the Yeshiva Rachi, named after the great exegete who studied in Worms. Since 1982, this building has housed the Jewish Museum of Worms, but it is not the first of its kind. The first Jewish museum in Worms dates back to 1924. It was the work of Isidor Kiefer (1871-1961), an active member of the Jewish community in Worms. He went into exile in the United States in 1933 after the Nazis came to power. During Kristallnacht, the museum was destroyed in the pogrom. Only a few rare pieces from the museum were saved.

The dozen or so Jews living in Worms today are connected to the community life in Mainz.

Itinerary

Leaving Worms station, turn right onto Bahnhofstrasse and follow the street to the end.

Opposite the theatre, which hosts many cultural events, turn left to reach the old Jewish cemetery in Worms.

The cemetery consists of several sections, the main one at the entrance and the others overlooking it, which were built when the cemetery was enlarged.

The Jewish cemetery of Worms is probably the oldest in Europe. Dating back to the 11th century, 836 graves have been recorded. Some are very ancient and others more recent, which can be seen on the small path above leading to the different sections.

After this visit, head back up towards the old town along the ramparts. You will come to numerous religious buildings, including the cathedral and churches of different denominations.

To reach the Judengasse, you cross the shopping street Kämmererstrasse, lined with fountains: the Siegfriedbrunnen (in honour of Siegfried, hero of Norse mythology),

the Winzerbrunnen (the Winegrowers’ Fountain pays tribute to the local wine culture and historical figures associated with viticulture)

and finally, the Ludwigsbrunnen (in honour of Grand Duke Louis IV of Hesse and the Rhine), on the square of the same name, celebrating the city of Worms.

At the end of this street, arriving at the Martinspforte, turn right into Judengasse.

At the beginning, you will see a kindergarten named in honour of Anne Frank. This section of the street is paved with old cobblestones, among which you will also find other types of cobblestones, known as Stolpersteine, marking the places where Jews lived before being deported during the Holocaust.

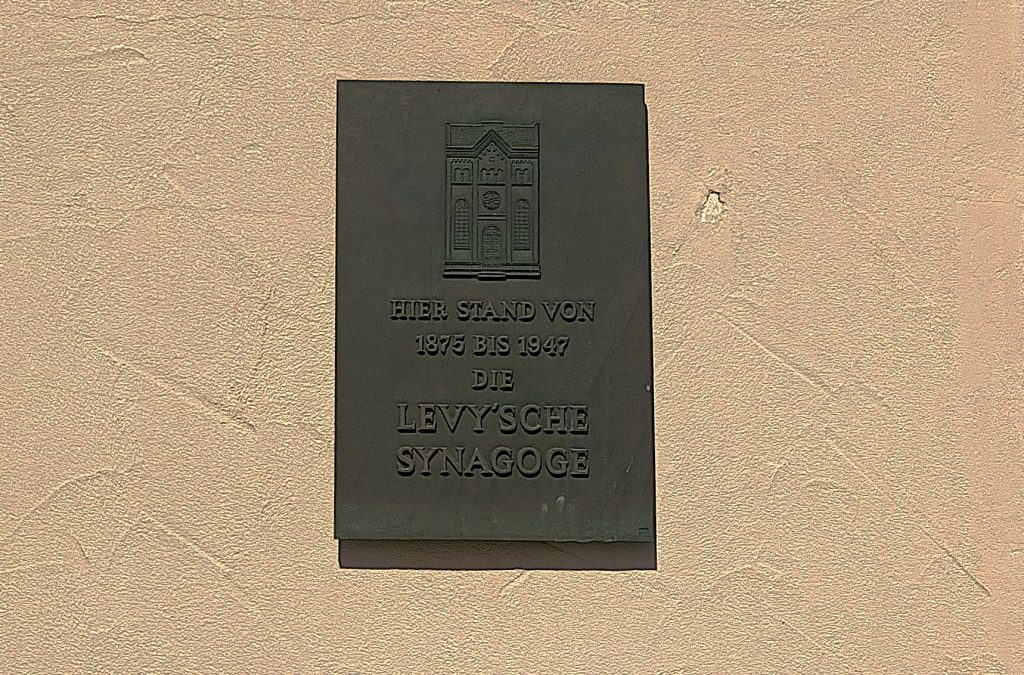

Judengasse leads to the synagogue and the Jewish Museum . Opposite the entrance to the synagogue is a commemorative plaque on a wall marking the site of the Levy Synagogue, which stood here from 1875 to 1947.

Upon entering the museum, visitors are greeted on the right by a video that tells the story of the building and provides a general overview of Jewish rituals.

Next to the video is a Sefer Torah. In the same room, visitors can see ancient objects and manuscripts protected by glass cases.

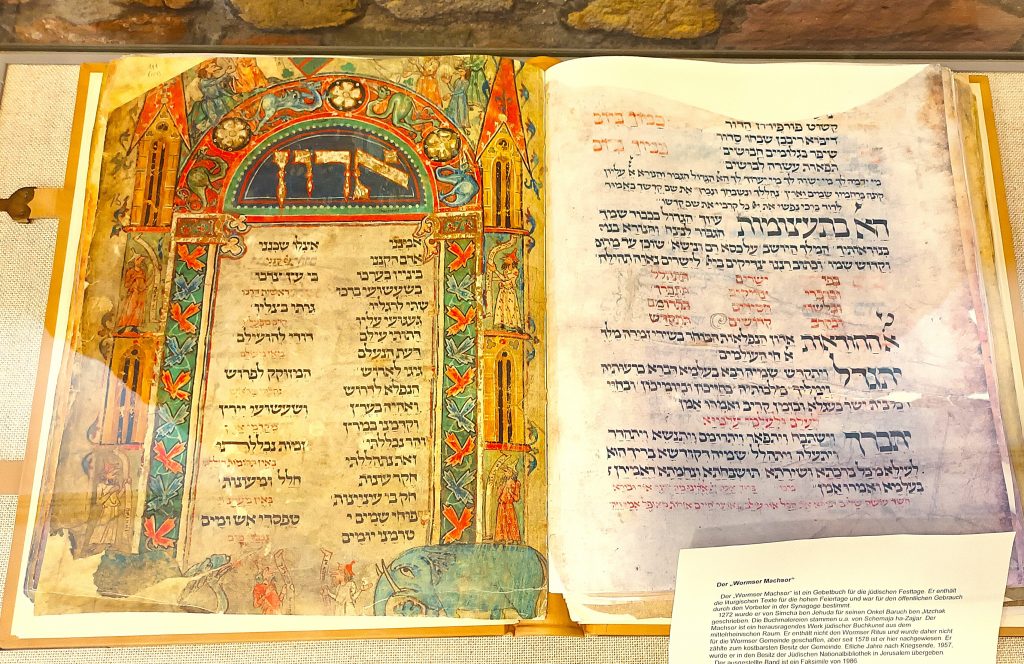

Among these important documents is the famous Mahzor of Worms, a collection of liturgical texts used by the synagogue’s cantor. This mahzor was written in 1272 by Simha Bar Judah. The original version is kept at the National Library of Jerusalem. The one on display at the museum is a reproduction dating from 1986.

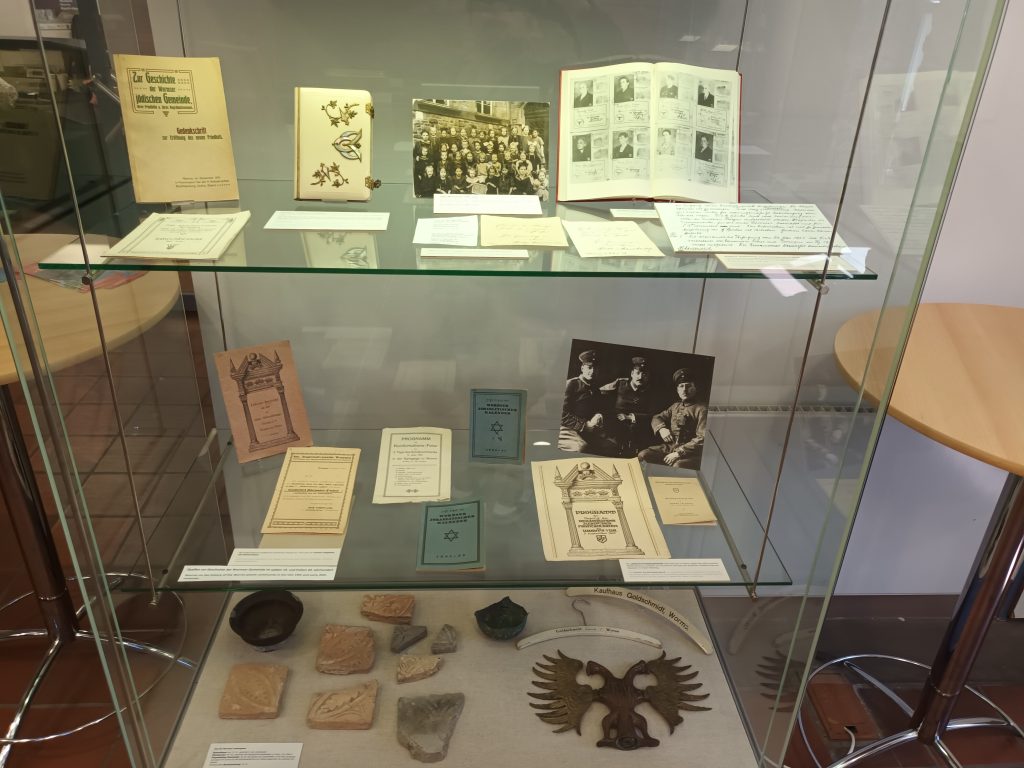

Other objects include books, of course, but also photos of schoolchildren and Jewish soldiers during the First World War. There are also portraits of prominent figures from the community and even coat hangers from the Goldschmidt store in Worms. This was the best-known and largest textile store in Worms, occupying most of the buildings between Domgasse and Hofgasse before the war.

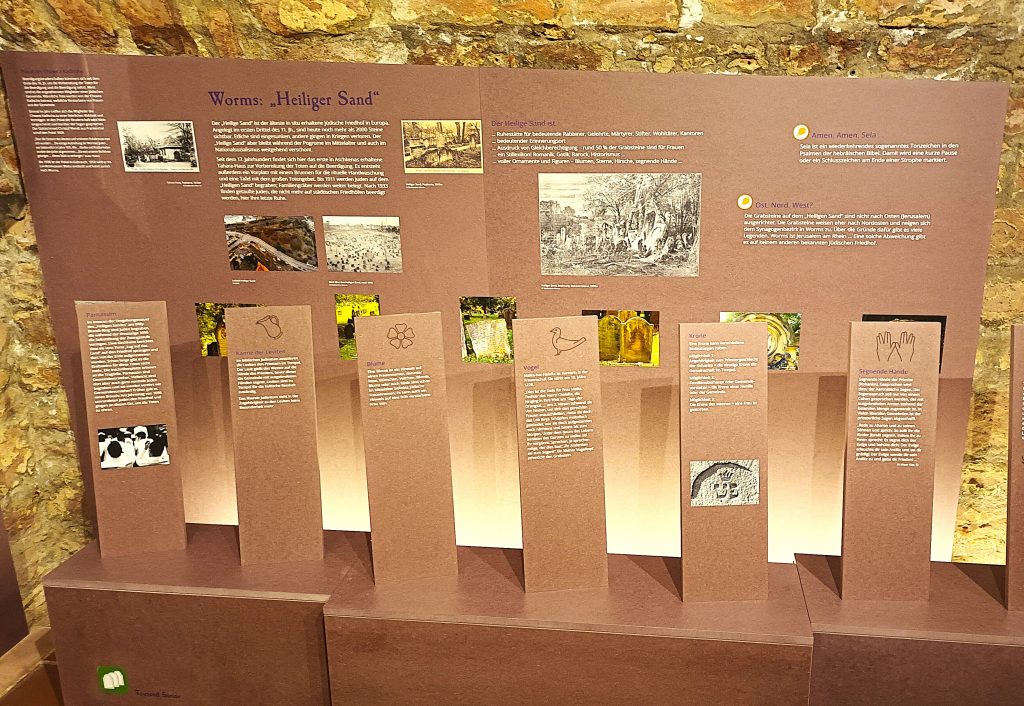

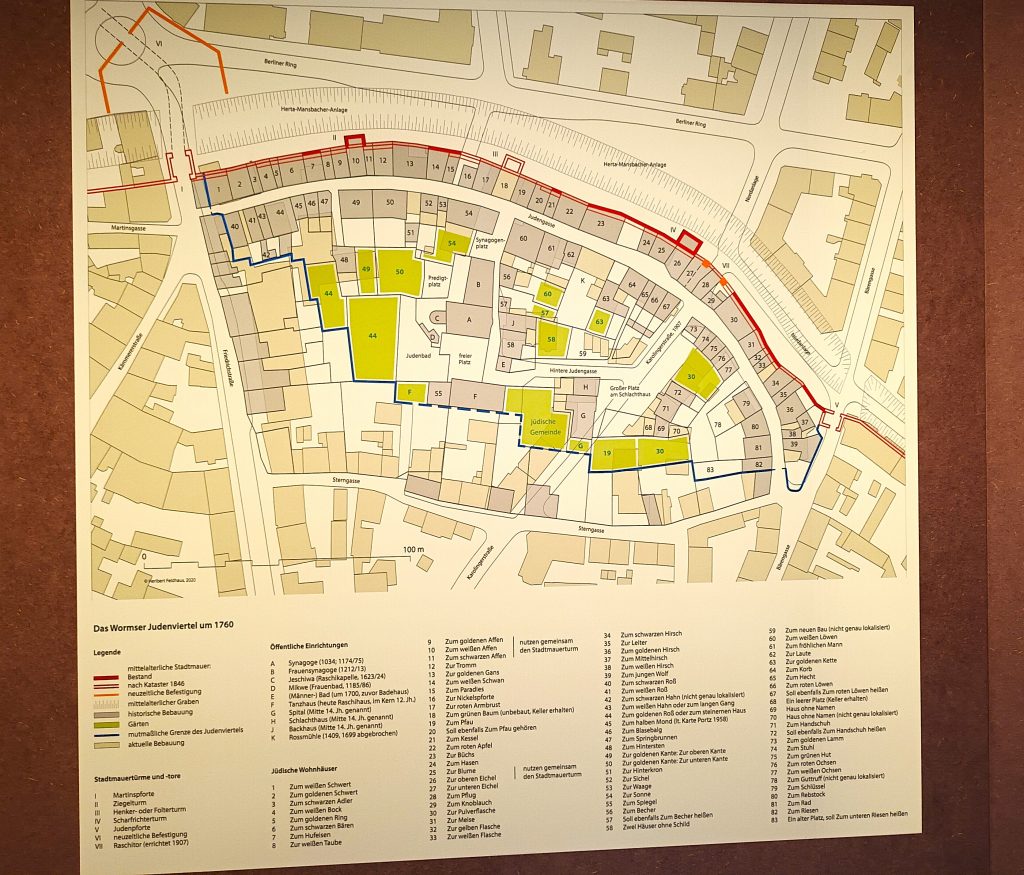

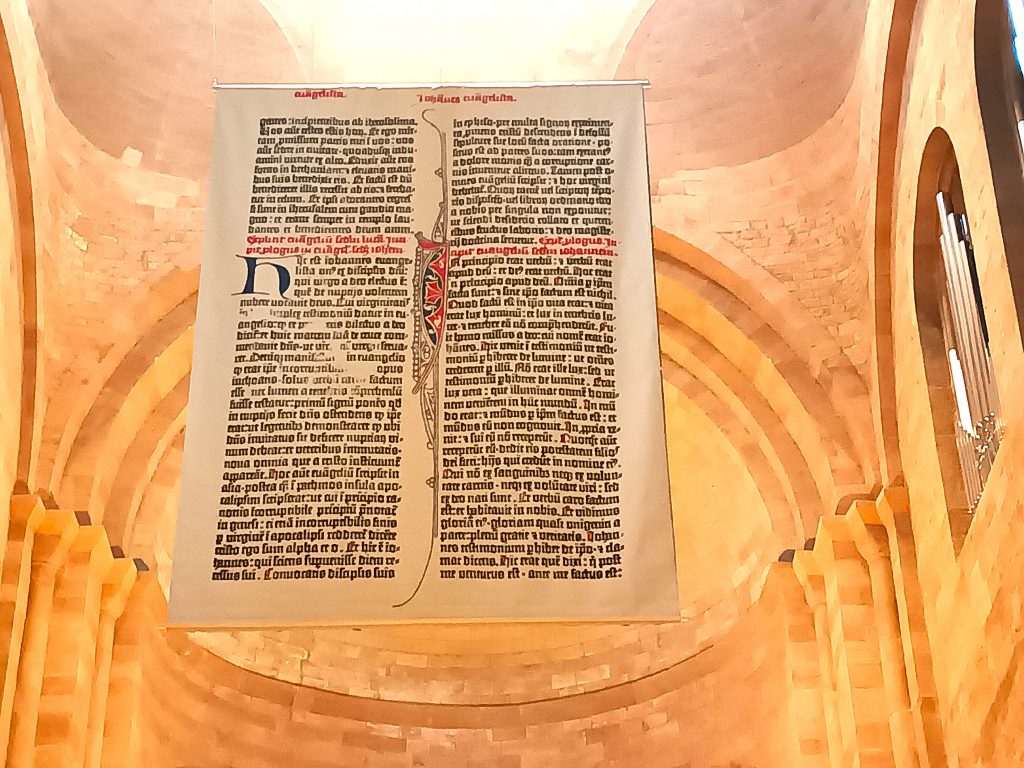

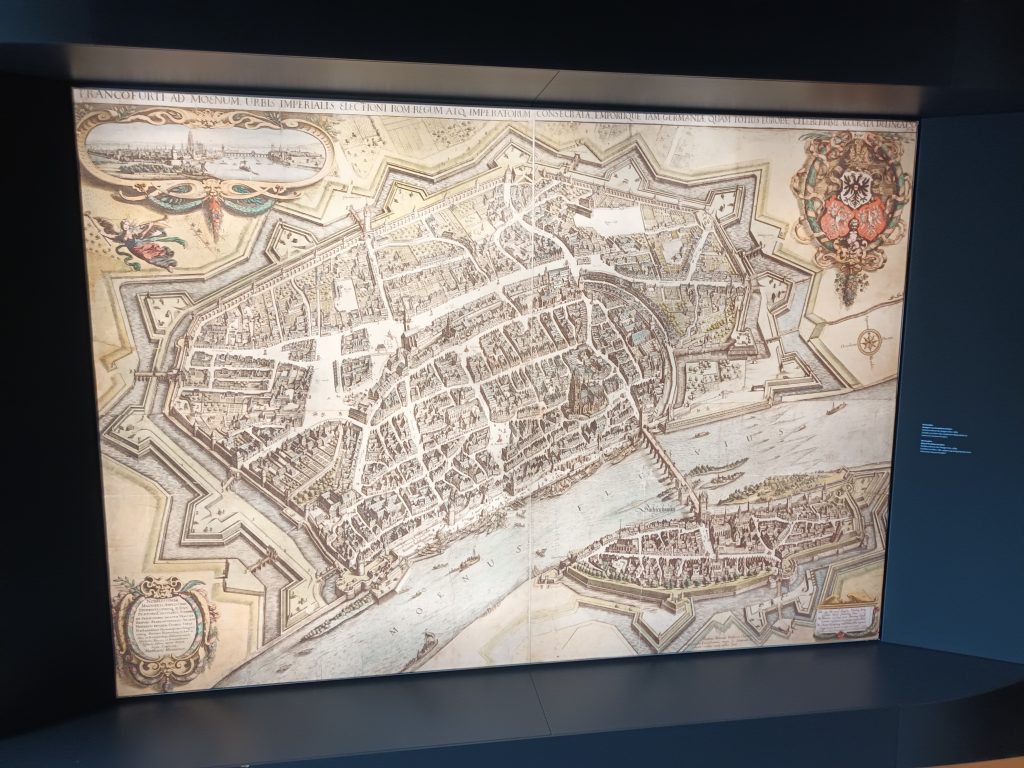

The room on the left consists mainly of panels presenting a wide variety of subjects: the general history of the Jews in the Schum region, the creation of the first Jewish museum by Isidor Kiefer, the celebration of the 900th anniversary of the synagogue in 1934, its reconstruction after the war, and a sideboard with the Hebrew word ‘Zakhor’ , meaning ‘remember’, in whose drawers you can read the biographies of Jews from Worms who were deported during the Holocaust.