Pernes-les-Fontaines remained the capital of Comtat Venaissin until Pope John XXII bought back the rights over Carpentras from its bishop. Two elements reveal the Jewish presence in this town: the name Place de la Juiverie and the traditional identification of the large house standing in that square as the old “Jewish baths”.

During Heritage Days in 2024, the Hôtel de Cheylus opened the doors of its mikveh to visitors. This mikveh dates back to the 16th century and has been listed as a historic monument since 1996.

Carpentras had a Jewish population when it was yielded to the papacy by the king of France in 1274. In the fourteenth century, the Jewish quarter on rue Fournaque, near the town walls, was home to ninety families.

In 1459, it was sacked by rioters, and sixty people were killed. The community was forced to move to rue des Muses in the town center, which became rue des Juifs, a carriere closed off at both ends by gates. During the fourteenth century, Jews lived mainly from trading agricultural products and money lending. A census in 1473 revealed sixty-nine Jewish families living in Carpentras. In 1523, Jacopo Sadoleto, the bishop of Carpentras, imposed restrictions on their activities, and the community shrank down considerably. After the expulsions of 1570 and 1593, only a few families remained, but in 1669, when the small communities of Comtat Venaissin were put in the four carrieres, the number rose to eighty-three families, of 298 persons.

New restrictions were imposed throughout the eighteenth century. There was, notably, a long, drawn-out conflict over the construction of the synagogue. Begun in 1741 in answer to the growing number of believers, the construction proceeded swiftly until, in 1757, the bishop obtained authorization from Rome to reduce the building to its medieval dimensions. He himself set about the demolition with the help of masons. The Jews protested, and the conflict dragged on until 1784, when a compromise was reached as to the acceptable dimensions. At the end of the eighteenth century, the community numbered some 2000 members. Most of them lived modestly, or even in poverty. Some, though, were rich, such as Jacob de la Roque and Abraham Crémieux. During the Revolution, the synagogue was a Jacobin meeting place. It returned to being a place of worship in 1800.

The community in Carpentras produced few renowned intellectuals. Most were doctors and poets. Mardochée Astruc, from Carpentras, wrote the play La Reine Esther with Jacob de Lunel in the eighteenth century. It inspired Esther de Carpentras, a comic opera with a libretto by Armand Lunel that was presented in Paris in 1938.

The synagogue was registered as a historical monument in 1924. A monumental staircase leads to the place of worship, which is organized on two levels: the meeting room with the tabernacle and the gallery/tribune with the tevah. The interior decoration is remarkable. Note the blue ceiling spangled with stars, the wooden paneling, the gilding on the tabernacle, the columns supporting the tevah, the Chair of Elijah, and the chandeliers and candlesticks. In the basement, elements from the medieval construction are still in place: the matzoh oven, the mikvah, and the women’s prayer room, where a specially chosen rabbi led the prayers in Judeo-Provençal (Judeo-Comtadin). The carriere and the Place de la Juiverie were destroyed in the nineteenth century.

In May 1990, the Jewish cemetery of Carpentras was desecrated by neo-Nazis. Thirty-four graves were vandalised. A large demonstration brought together hundreds of thousands of people in Paris, including President François Mitterrand and Simone Veil.

Every summer, Carpentras hosts the Festival of Jewish Culture and Music. The 2025 edition, held from 10 to 12 August, featured musical readings and concerts at the synagogue and in the Cour de la Charité. Performers included Romanceo Sefardico, Aude Marchand, Pletzl Bandit, Bad Brapad Acoustic Trio and Kalistrio.

The first attestation of a Jewish presence in Avignon dates from the fourth century. It is a seal representing a five-branch menorah and bearing the inscription avinionensis. Jewish commercial activity was intense under Avignon’s Popes. The tailor of Gregory XI was a Jew, as was his bookbinder.

During the Black Death epidemic in 1348, the community in Avignon was spared popular wrath thanks to the energetic intervention of Clement VI. The edicts of 1558 included a description of the community’s organization. Its members were divided into three categories according to wealth. The baylons, for example, were responsible for collecting taxes, charity, caring for the sick, and teaching. In the seventeenth century, Jews worked mainly in secondhand trade and horse dealing. When the city became part of the French Republic in 1791, the number of Jews in Avignon fell quickly. By 1892 there remained only forty-four families. The arrival of Sephardic Jews in the 1960s revived the community.

Avignon was the birthplace and home of many important figures in Hebrew literature. Among the best-known were Kalonymos ben Kalonymos, the author of Even Bohan (The Touchstone) a satire of Jewish life in Provence during the Middle Ages, and Levi ben Gershom (Gersonides).

The Jewish quarter was opposite the Palace of Popes, as indicated today by rue de la Vieille Juiverie. Around 1221 it was transferred to the Place de Jérusalem (now Place Victor Basch). The carriere was rue Jacob, where some of the old houses can still be seen. It was surrounded by a wall with three gates.

The old synagogue was destroyed by fire in 1845 and replaced by a new, circular one, which can be visited.

During the Nazi occupation, this village in the department of Ain was the scene of a raid ordered by Klaus Barbie on 6 April 1944. Forty-four Jewish refugee children and their seven teachers were arrested and deported. Only one survived.

The Memorial Museum of the Children of Izieu (Musée-Mémorial des enfants d’Izieu) exhibits letters and drawings in honor of these victims of Nazi barbarity, who lived in the village for nearly a year. An adjoining building has audiovisual displays that recall those dark years, exploring the concept of “crimes against humanity” and showing excerpts from the Barbie trial concerning the crime at Izieu.

The Jewish community in the historical capital of the Gauls and, for historians, capital of the French Resistance, has now regained an undeniable dynamism. There are many notable sites surrounding the Grand Synagogue , built in 1864, as well as some excellent restaurants. All in all, they make Lyon a very pleasant stop.

As in many French cities, the presence of Jews there probably dates back to the Roman Empire, but was recorded in the Middle Ages.

This, from the 9th century, when they formed an important community. They then lived near rue Juiverie, at the foot of Mont Fourvière.

The Jews were expelled in 1250, but resettled there a hundred years later. Another round trip of this kind took place at the beginning of the 15th century.

The sustainability of Jewish life in Lyon took shape with the French Revolution, as in many other cities of France. Made up of families from Comtat Venaissin, Alsace, Bordeaux and Avignon, they bought land to establish a cemetery.

From 300 in 1830, the number of Jews rose to 700 in 1840, mainly thanks to the arrival of Jews from Alsace-Lorraine. They lived largely on rue Lanterne and rue de la Barre.

In 1864, the Grand synagogue of Lyon was opened at Quai Tilsitt. Long discussions took place with the authorities. The municipality made available the salt granary land in 1862 and it was built by the architect Abraham Hirsch.

The city also hosts a Sephardic rite synagogue, Neveh Chalom , built in the early 20th century by Jews from Greece and Turkey.

Large center of the Resistance, the Jews took part in it considerably. It was in this city that Jean Moulin, sent by General de Gaulle to organize the Resistance, was arrested and tortured.

Cardinal Pierre Gerlier publicly denounced the abuses committed against the Jews and participated in the efforts of the Resistance.

If the city of Lyon counted only 7000 Jews after the war, this figure increased rapidly with the reindustrialisation and the arrival of the Jews of North Africa. Thus, in 1969 there were nearly 20,000 Jews in Lyon.

The city also has a Jewish cemetery.

There are also Jewish communities in the cities of the region, mainly in Villeurbanne. Several synagogues, mikvaot and study centers have settled there.

The Cultural Institute of Judaism recently opened in Lyon. In a republican spirit, it facilitates the discovery of Judaism thanks to an educational approach on different levels, combining presentation of old objects and use of the latest technological innovations (giant screens, digital tablets, virtual reality). It also regularly organizes visits for high school and college students in the region.

The course is organized around the following themes: the history of the Jewish people, religion and religious practices, anti-Semitic prejudices, and the place of Jews in France.

On 26 January 2025, to mark the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz, the Rails of Remembrance monument was inaugurated in Place Carnot. Opposite Perrache station, from where the convoys of deportees left. The work, created by Quentin Blaising and Alicia Borchardt, is made up of 1,173 metres of track, representing the exact number of kilometres separating Lyon from Auschwitz.

Interview with Ilan Levy, journalist and guide

Jguideeurope: How do you perceive the development in recent years of Judaism in Lyon and of the general interest in places of reference for Jewish cultural heritage?

Ilan Levy: Lyon is fortunate to have a synagogue listed in the Supplementary Inventory of Historic Monuments: the Tilsitt synagogue. This place of worship is very important for the Lyonnais, especially because so many weddings take place there. Visits are organized there throughout the year, outside the Covid period, in particular by school groups.

Recently renovated, on the occasion of its 150th anniversary, the synagogue has had a complete makeover. It is possible to admire the stained-glass windows and the organ, as well as the architecture proposed by Abraham Hirsch, the architect of the city of Lyon at the end of the 19th century, which gives it a look close to a Protestant temple. It is also the subject of numerous visits during the yearly Heritage Days organized all over in Europe, and concerts are given there at each “Music Feast”.

Is there a lesser-known place linked to this heritage that you think is important to know?

Outside of the Tilsitt Synagogue, the Jewish heritage is more recent and does not offer an architecturally remarkable building. The Cultural Institute of Judaism, built next to the Névé Chalom synagogue, was inaugurated in 2020. It offers an educational path, using the latest technological discoveries, on Judaism, its history and its traditions. It aims to make known the Jewish religion, its rites, its festivals, its liturgy and, thus, to fight against prejudices and anti-Semitism. While strolling in its alleys, the public will discover the many Jewish festivals, the traditions and will be able to attend a Shabbat service in 3 D at the Tilsitt synagogue.

Lyon has an important place in the history of the Resistance. How does the city promote the cultural sharing of this history? In what places?

The city, capital of the Resistance, offers several high places of this history. The Center for the History of the Resistance and Deportation is an educational place to visit for its permanent collection and exhibitions. During the war it was the place where the Gestapo and the sinister Klaus Barbie tortured resistance fighters in the cellars of this former health institute. Note that the Comoedia cinema, opposite the CHRD, was also used as a cinema by the Nazis during the war. Klaus Barbie, the head of the Gestapo, the “butcher of Lyon” did not hesitate to go and find the resistance fighters at Fort Monluc during the day to torture them and bring them back in the evening to the sinister prison of this fort.

The Fort Montluc is a military prison built in 1921. From 1940 to 1942, it served as a prison in Vichy before being used by the Nazis who locked up Jews and resistance fighters there. In appalling conditions, several in cells, they are crowded into the prison and tortured during the day. The Jews are interned in the “Jewish hut”, a kind of wooden warehouse, which no longer exists today, in the courtyard under even more appalling conditions. They are most often then taken to Perrache station to be deported and exterminated in Auschwitz.

The 44 Jewish children of the House of Izieu and their companions, whom Barbie will round up in their colony of Ain on April 6, 1944, will pass through Montluc before being deported and exterminated. From this prison, only André Devigny, a French soldier and resistance fighter, managed to escape in August 1943 in order to escape his death sentence. This episode will be the subject of Robert Bresson’s 1956 movie A Man Escaped.

The prison will remain active after the war, then become a prison for women before closing permanently in 2009 and becoming a National Memorial. When France, thanks to the work of the Klarsfeld couple, had Klaus Barbie arrested in South America, the Justice Minister Robert Badinter, whose father was deported by Barbie during the Raid on rue Sainte Catherine, had him stay at the Montluc prison before his trial. The court with 24 columns of this historic trial is located on the Quais de Saône in front of a few hundred meters from the Tilsitt synagogue.

A plaque is affixed at 12 rue Sainte Catherine to commemorate the raid organized by Klaus Barbie on February 9, 1943 in this office of the General Union of the Israelites of France where 86 people were arrested and deported. Another plaque has existed since 2016 on rue Boissac where the Consistory offices were held during the war. Finally, after Montluc and the CHRD, an hour’s drive from Lyon, is the Maison d’Izieu Memorial, a symbolic educational center of the genocide of Jewish children.

The Jewish presence in Hégenheim seems to date back at least to the 17th century. 14 Jewish families were counted in 1689. Jewish life developed there, the community growing to more than 400 people on the eve of the French Revolution. One of the largest in Alsace at the time, the number of its faithful declined over time. Thus, in 1936, there were only 36 Jews left in Hégenheim.

On the Franco-Swiss border, the Hégenheim cemetery , which covers over five acres, has tombstones dating from its establishment in 1673. It is the only cemetery to have preserved a wooden funeral slab. The original is now on exhibit in the Jewish Museum in nearby Basel. This busy Swiss trading town was long a magnet for local inhabitants and, since they were refused the right to reside there, Jews settled in the nearby areas of Alsace and, for two centuries, the cemetery at Hégenheim was used by local communities, including those across the Swiss border. It is now a moving historical site where you can walk among more than 7000 tombs and discover weathered stones overgrown with ivy or scattered among the overgrowth.

The ancient synagogue of Hégenheim will become a cultural centre dedicated to contemporary art, concerts and conferences.

Once in an Alsatian town

“[One rue des Juifs] All one could see were tall, decrepit buildings, furrowed with rusting gutters: and from the dormer windows the whole of Judaea hung its stockings, dirty old petticoats, patched underwear, and frayed linen. At all the basement windows could be seen doddering heads, toothless mouths, noses and chins like carnival masks; you would have though that this people came from Nineveh, from Babylon, or that they had escaped from captivity in Egypt, so old did they look.”

Émile Erckmann and Alexandre Chatrian, Friend Fritz (Strasbourg: Édito, 1966).

The Jewish presence in Colmar probably dates from the 13th century. Administrative documents confirm this presence. A synagogue was destroyed in 1279.

The community grew, in particular thanks to the arrival of Jews from Rouffach and Mutzig. Thus, in the 14th century, it managed a synagogue, a mikveh, a reception hall and a cemetery. Persecuted during the Black Death, the Jews were readmitted to Colmar at the end of the century. Throughout the following centuries, the Jews of Colmar were sometimes readmitted and sometimes victims of injustice. It was only after the French Revolution that their lot improved, with access to citizenship, as in the majority of the country. A first synagogue opened at the very end of the 18th century.

In 1800, there were 140 Jews living in Colmar. In 1808, Colmar welcomed a consistory on which 25 surrounding communities depended. Fifteen years later, the city also hosted the headquarters of the Chief Rabbinate of Alsace.

The Jewish population increased significantly, reaching 513 in 1833. In 1843, the synagogue of Colmar was inaugurated and represented one of the most beautiful architectural monuments of the city. This number doubled on the eve of the 1870 war. As many Jews left the region following the defeat, the fall stopped and the Jewish population even increased in the 20th century, reaching its peak of 1200 in 1935. The Shoah claimed many victims in the region and affected a third of Colmar’s Jews. The synagogue was ransacked by the occupiers. After the war, Jewish life was rebuilt thanks to the arrival of Jews from North Africa. Thus, in 1990, there were 1000 Jews in Colmar.

Old cemeteries on the road to Rouffach and at the Theinheim gate were used before 1800, and then the Ladhof cemetery .

The Bartholdi Museum pays homage to the sculptor of the Statue of Liberty. One room features an interesting collection of Judaica. Particularly admirable is a bowl used by the brotherhood charged with final duties (Hevra Kadisha); it is in the form of a coffin with bearers (mid-nineteenth century). There are also precious examples of circumcision chairs and an ablution fountain from the cemetery at Herrlischeim.

In 2021, the PMC in Colmar hosted a conference on René Hirschler, a rabbi who took part in the Résistance. At this event, Alain Hirschler paid tribute to his parents. The youngest rabbi in France at the age of 23, René Hirschler was appointed to Mulhouse in 1929, then became Chief Rabbi of Strasbourg. Mobilized in 1940, he was appointed by Vichy as the Jewish chaplain of the camps in the southern zone. This appointment allowed him to organize with his wife Simone an assistance and rescue of prisoners. Simone and René Hirschler were arrested and died in deportation in 1944.

In November 2025, as part of the ‘Tuesday evenings with religions’ event, initiated by the European Community of Alsace, the Colmar synagogue opened its doors to the Colmar public.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, judaisme.sdv.fr and dna.fr

Traces of the old Jewish community can still be seen in this charming tourist town.

On ruelle des Juifs, an arched doorway with an engraving in Hebrew signals the entrance to the old synagogue, dating to 1454. On rue du Général-Gouraud the voussoir of an arch bears the Hebrew date 5456, corresponding to 1696 C.E. In the porch, note the two blessings hands carved in stone with the inscription “The master, rabbi Samson, the Cohen”.

Long the walls of the synagogue, you will observe the vestiges of a Jewish community house built circa 1750 with traces of the Holy Ark and altar. The hammered lilies recall that the French kings protected the Jews of Alsace (in the courtyard, an image reproduces the place of worship). When the ancient synagogue became too small, it was deconsecrated in 1876 and replaced by the neo-Romanesque one still in use today.

Nevertheless, the Jewish population of Bern declined throughout the 20th century, from 144 in 1910 to 138 on the eve of the Second World War. Following the Holocaust, the synagogue damaged by the occupiers was restored in 1948. In 1970, there were only about 60 Jews in the city. In 2021, this number is estimated to be around ten or fifteen families.

Among the personalities of Oblast, it is difficult to forget André Néher, the famous thinker and teacher. An André Néher square was inaugurated in 2000. Twelve Stolpersteine were placed in the streets of Obernai in June 2022 in memory of an Obernese victim of the Shoah.

In 2024, a book devoted to the Jewish community of Obernai was published by Jean Camille Bloch and presented during the European Days of Jewish Culture.

A duo of musicians, Ezriel Ehrlich and Arthur Julié, gave a concert on 2 March 2025 at the Obernai Synagogue, combining Alsatian liturgy, klezmer music and Yiddish. On 13 July 2025, the synagogue welcomed around fifty Jewish worshippers from Pforzheim (Germany).

The Jewish cemetery of Obernai was acquired at the beginning of the 20th century.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, judaisme.sdv.fr, dna.fr

The Jewish presence in Rosenwiller dates back at least to the 14th century, a writing by Charles IV, mentioning the Jewish cemetery. A letter dealing with a dispute with a certain Haym de Rosenwiller, addressed to the Strasbourg Magistrate in 1550, was also found.

In 1727 the Jews, who had been burying their dead here for nearly four centuries, were granted permission to build a wooden fence around the cemetery and, twenty-two years later, a stone wall. With 6470 tombs over twelve acres, Rosenwiller’s Jewish cemetery bears witness to a long history: the oldest tomb dates from 1657.

As you walk through the old part of the cemetery, you will find here and there small Hebrew poems to the glory of the deceased and recurring symbols: broken columns for children and young women who died without offspring, Shabbat lamps for pious women, jugs for the Levites, blessing hands for the Kohanim (according to tradition, the Levi and the Cohen come from tribes consecrated to the priesthood).

A collective book published in 2020, Rosenwiller: a Jewish presence throughout the century (I.D. Editions) tells the long Jewish history of Rosenwiller. That of the cemetery, but also the daily life of the Jews in the town, with its moments of happiness and turmoil. By presenting personal stories, objects, the Holocaust and the people involved in the rescue of the Jewish cultural heritage of Rosenwiller.

In 2022, 93-year-old death camp survivor Simone Polak unveiled a plaque at the Rosenwiller Jewish cemetery in tribute to her grandparents Caroline and Benjamin Bloch, the last guardians of the cemetery.

During the European Days of Jewish Culture and Heritage in 2025, a guided tour of the Jewish cemetery in Rosenwiller was organised for around fifty people to raise awareness of Rosenwiller’s Jewish history.

The Knacker’s Square

“When the Jews asked for a place to bury their dead (around 1350), they were shown a huge, arid square in Rosenwiller at one end of which the slaughterer buried dead horses. At the other end, they were allowed to bury their deceased coreligionists”.

Élie Scheid, Histoire des Juifs d’Alsace (History of the Jews of Alsace), 1887 (Paris: Librairie Armand Durlacher, Reprint Willy-Fischer, 1975).

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr, Akadem

In this suburb of Strasbourg, one can see a fine eighteenth-century mikvah. A room dedicated to Davis Sintzheim (the first Grand Rabbi of France and director of the Talmudic school in Bischheim between 1786 and 1792) retraces the history of the Jewish community and houses temporary exhibitions.

The Jewish presence in Bischheim seems to be very old. Many Jews who worked during the day in Strasbourg without having the right to settle there lived with their family in Bischheim. This was probably already the case at the beginning of the 17th century.

If there were a little less than 40 Jewish families in Bischheim in 1774, this number doubled in ten years. In the middle of the next century, 759 Jews lived in Bischheim. But this number gradually decreased, reaching less than 300 at the turn of the 20th century. In 1936, half of them died in the Holocaust. The community tried to rebuild itself after the war. There were 52 Jewish families in 1959.

Among the great people who lived in Bischheim, how can we not mention Cerf-Berr. Having played a great role in the emancipation of the Jews. In particular, thanks to the text of the philosopher Moses Mendelsohn who wrote a plea for the improvement of the situation of the Jews in Europe. This text influenced other intellectuals, religious and political leaders who helped to advance access to citizenship for the Jews of France. David Sintzheim, Cerf Berr’s brother-in-law, became the first Chief Rabbi of France and presided over the Sanhedrin assembled by Napoleon. Among the other personalities of the city was Chief Rabbi Isaac Baer, who had one of his successors, Zadoc Kahn, as a student in the city.

The first synagogue in Bischheim was founded by Cerf Berr around 1780. The place quickly became too small, and another synagogue was inaugurated in 1838. At that time, the city also had a Jewish school with about 100 students. There was also a mikveh belonging to David Sintzheim. The synagogue was destroyed during the Second World War and rebuilt in 1959.

For a long time, the Jews of Bischheim were buried in the cemeteries of Rosenwiller and Ettendorf. Since 1797, the community has a cemetery , located between Bischheim and Hoenheim.

The mikvah and the museum hosting it can only be visited via reservations by email and phone.

Paving stones in memory of a family murdered at Oradour-sur-Glane and four members of the Resistance have been installed in Schiltigheim and Bischheim in 2024. On 28 April 2025, Stolpersteine were laid in tribute to five victims of Nazism during a ceremony.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, DNA and judaisme.sdv.fr

Strasbourg, the regional capital, is also home to the European Parliament, as witnessed by the European flags welcoming you at the train station. This magnificent city, at the heart of many political, national and religious conflicts over the centuries, has become a symbol of political, national and religious reconciliation and cooperation. Crossing its many bridges to the magnificent architectural imprints of the centuries and the cultural and gastronomic activities on offer await you…

Jewish history is constantly present here. Is it not said that the rue de la Nuée-Bleue owes its name to the cloud that preceded the Jews expelled from the city in 1349, and that the rue Brûlée evokes the Jews burned alive that same year for refusing baptism?

The Jewish presence in Strasbourg has been attested to since the 12th century and, according to some researchers, is even older. The community had a synagogue, a mikveh and a cemetery. On Valentine’s Day, February 14, 1349, the Jewish population of Strasbourg was massacred. The few Jews who had fled in time were gradually allowed to return to Strasbourg, mainly as a result of an ordinance of 1375. But their banishment was promulgated in 1389. It remained in force until the French Revolution. During all these centuries, they had the right to stay for work, but had to pay an entrance tax. They lived in villages in the region that were more welcoming. At the beginning of the 17th century, the Jewish population of Alsace began to grow. At the end of the century, the rabbinate of the Jews of Alsace was created.

On the eve of the Revolution, some Jews managed to make timid progress towards the emancipation of their people. But the one who made the greatest impression was undoubtedly Hirtz de Mendelsheim, better known as Cerf-Berr. A contractor for the King’s armies, he succeeded, not without difficulty, in obtaining the right to settle in Strasbourg in the 1770s. He fought hard for the emancipation of the Jews, succeeding in abolishing in 1784 the corporal toll imposed on the Jews. He also helped the city of Strasbourg to fight against famine.

From 19 to 25 May 1789, a delegation of 37 delegates met in Strasbourg to draw up a book of ‘grievances and wishes of the Jewish nation of Alsace’. Nevertheless, it was not until after the Revolution, in 1791, that Jews were officially allowed to settle in Strasbourg. The community began to form, with David Sinzheim, Cerf-Berr’s brother-in-law, as its first rabbi. The Grand Sanhedrin met on 9 February 1807, presided over by David Sinzheim, who was later appointed Chief Rabbi of the Central Consistory of France.

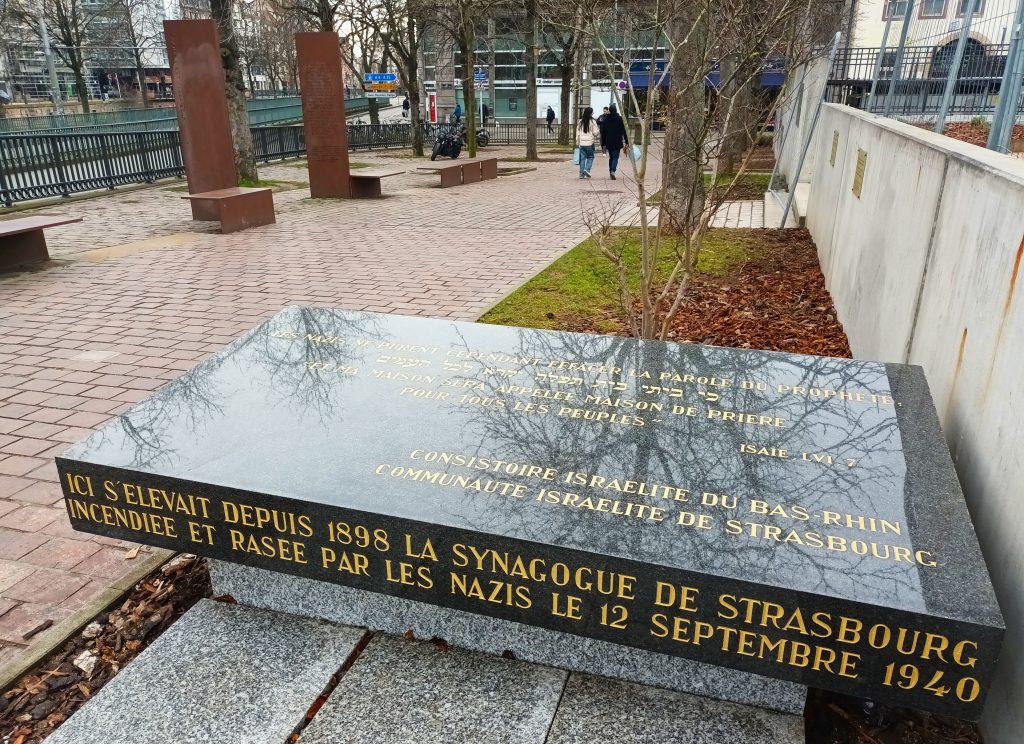

From 1811 to 1834, the congregation met in the former Poêle des Drapiers, then in a synagogue built in rue Sainte-Hélène in 1834. The rapid growth of the community necessitated the opening of a new synagogue on rue Sainte-Hélène. Built by the architect Ludwig Lévy, the Quai Kléber synagogue was inaugurated on 8 September 1898, replacing the previous Jewish places of worship.

On the eve of the Second World War, the city had 10,000 Jews in Strasbourg. Following the capitulation of France, they escaped to other regions, reconstituting their community, mainly in Périgueux and Limoges. René Hirschler, the Chief Rabbi of Strasbourg, ensured the link with the dispersed Jews of Strasbourg and undertook courageous work to save the prisoners who might be deported. Mobilization in the Resistance and to help the population was also done through associations such as the EEIF and the OSE. Many of these resistance fighters from Strasbourg died on the battlefield.

The monumental synagogue on the quai Kléber was burned down by the Nazis in 1940. One thousand Jews from Strasbourg were murdered during the Shoah. After the war, eight thousand Jews resettled in the city.

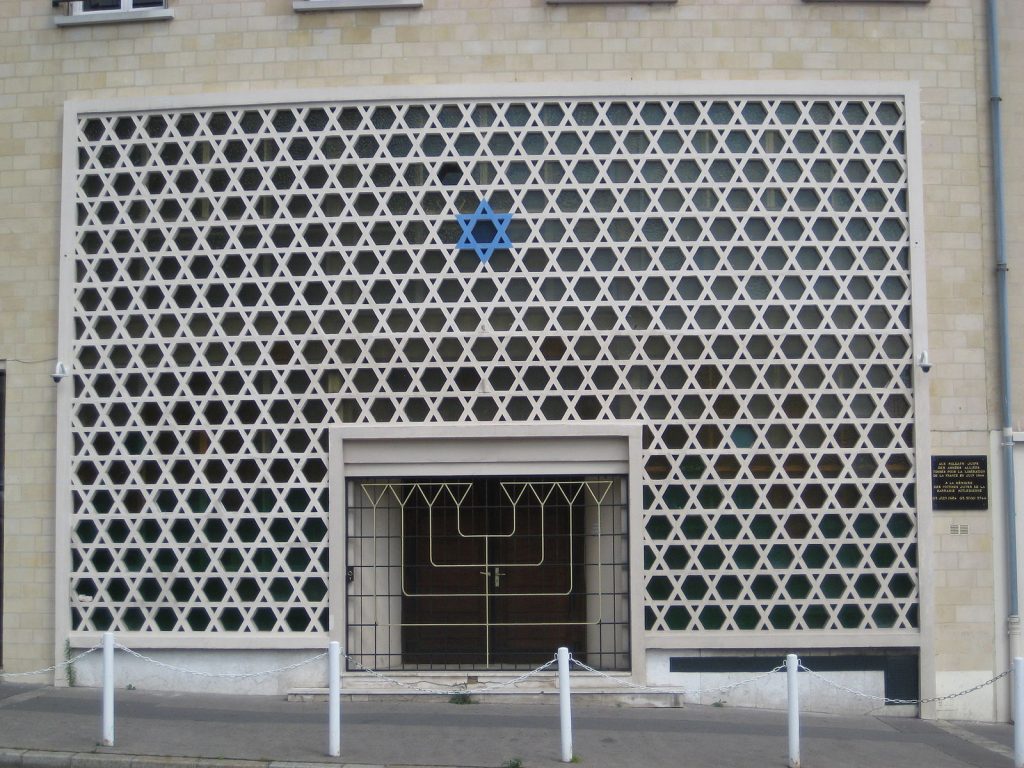

From 1950 to 1958, the city made a building in the former Arsenal available to the Jews of Strasbourg. The Synagogue de la Paix (Peace Synagogue) is located in the Neustadt district, with its impressive Prussian-style buildings, built between the 1880s and the First World War and enabling the city to triple in size. The synagogue was designed by the architect Claude-Meyer-Lévy and can accommodate 1,600 worshippers. Its main façade is decorated with a wave of Stars of David. On 13 March 1958, the Strasbourg community inaugurated this major new place of worship, in the presence of the Mayor of Strasbourg Charles Altorffer, the Minister of State Pierre Pfimlin, the Chief Rabbi of France Jacob Kaplan, Charles Ehrlich (President of the Community), Joseph Weill (President of the Consistoire) and Abraham Deutsch (Chief Rabbi of the Bas-Rhin). On 22 November 1964, General De Gaulle presided over ceremonies marking the 20th anniversary of the liberation of Strasbourg by General Leclerc’s troops. He visited a number of monuments, including Notre-Dame Cathedral and the Synagogue de la Paix. Simone Veil, a former deportee who became Minister of Health from 1974 to 1979, then First President of the European Parliament from 1979 to 1982, made a high-profile visit to the synagogue in 1988.

Inside, you’ll admire the holy arch, whose bold shapes highlight a tapestry by the artist Jean Lurçat. The site is actually home to five synagogues, including one following the Ashkenazi rite of the Rhine Valley and another combining Ashkenazi and Sephardic rites, sometimes during the same ceremony! The large René Hirschler hall is used for major celebrations.

The arrival of North African Jews in the 1960s, mainly from Algeria and Morocco and a few families from Tunisia, encouraged the transformation of the Léo Cohn village hall into an oratory, followed by the inauguration of the Rambam synagogue in the early 2000s.

In 1868, Oscar Berger-Levrault demolished the old buildings on the corner of rue des Juifs and rue des Charpentiers to build a new printing works. A mikveh dating from the first half of the 13th century was discovered at the time, but not preserved or even photographed. Much later, during renovation work in 1984 in the Rue des Juifs, it began to be preserved and inscribed in the city’s monuments list. The central element consists of a square room of 3 meters on each side made of gray sandstone topped with red bricks. In each corner, Romanesque corbels remain.

The Esplanade synagogue was inaugurated on 12 April 1992 in rue de Nicosie. At the time, it was located in an area marking the growth of the Jewish population a little further away from the city centre.

As confirmed by Alain Fontanel, the deputy mayor of Strasbourg, in 2018 to the Akadem website, following the death of Simone Veil, the city had wished to pay tribute to her. Thus, the Avenue de la Paix, was renamed Avenue de la Paix – Simone Veil. In order to honor her fights for women’s rights, European unity and the memory of the Shoah. A very strong nomination symbolically since this avenue was previously named the German street, then the Daladier street and during the occupation, the Hermann Goering street!

In 2019 was inaugurated the place Jean Kahn, located opposite the synagogue. This, in tribute to this great figure of French Judaism. A year earlier, the mikveh on rue des Charpentiers was reopened. A rare occurrence in France, the Jewish population of Strasbourg has increased in recent years, with the development of institutions and the diversification of currents, both Orthodox and liberal. In 2025, the Jewish population of Strasbourg represents about 20 000 persons.

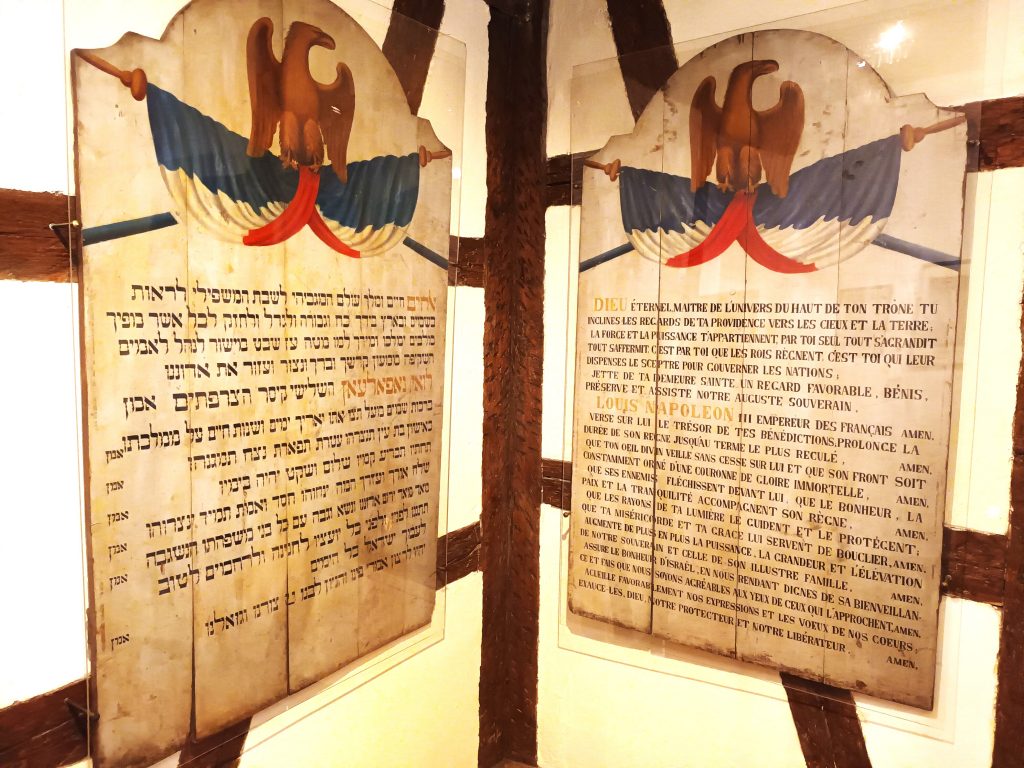

In the Alsatian Museum a small country oratory is reconstituted with its library, its Torah scroll and its Shabbat lamp. Two other rooms are dedicated to Judaism. There are some curious pieces, such as a carved wooden Star of David with a double-headed imperial eagle from 1770.

But also panels in Hebrew and French from the synagogue of Jungholtz calling for divine blessings on Emperor Napoleon III, and a painting commemorating the “Inauguration of a Pentateuch in Reichshoffen on November 7, 1857”, a moving evocation of fervor and patriotism.

In the courtyard of the Musée de l’Œuvre Notre-Dame dedicated to the arts of the Strasbourg region between the eleventh and seventeenth centuries, one can see Jewish funerary steles from the medieval cemetery that was located on the site of the current Place de la République.

On 23 January 2025, the AEPJ (European Association for the Preservation and Promotion of Jewish Culture and Heritage), which is responsible for the European Days of Jewish Culture, celebrated its 20th anniversary in Strasbourg. This is no coincidence, given the symbol of European reconciliation that Strasbourg represents, but also the crucial role played by local and Luxembourg personalities, notably Claude Bloch and François Moyse, in setting up AEPJ. The Council of Europe, under the auspices of the Luxembourg Presidency, hosted the event on 23 January, which was attended by Claude Bloch (Honorary President of the AEPJ) and François Moyse (President of the AEPJ), Björn Berge (Deputy Secretary General of the Council of Europe), Eric Thill (Minister of Culture of the Grand Duchy of Luxembourg), Catherine Trautmann (former Minister of Culture, former Mayor of Strasbourg and currently a municipal councillor), Gabrielle Rosner-Bloch (Regional councillor for culture and religion, in charge of heritage for the Grand Est Region) and Irena Guidikova (Head of the Department for Democratic Institutions and Freedoms).

Jguideeurope was delighted to take part in the day’s events, which included lectures on medieval Judaism in Alsace, Erfurt and the Iberian Peninsula. This was followed by visits to Strasbourg (in particular the Synagogue de la Paix) and a reception at the Residence of the Permanent Representation of Luxembourg. A day where speakers and participants recounted many moving personal stories and signs of hope for the future, such as the revival of Jewish culture in Poland. Above all, they repeatedly reaffirmed their commitment to the fight against anti-Semitism in all its forms, the preservation of cultural heritage and the sharing of humanist values between peoples. This is particularly important 80 years after the liberation of Auschwitz.

ITINERARY

This itinerary will enable you to discover the places mentioned in connection with Jewish life in Strasbourg, both past and present. It’s just under 4 km starting at the Strasbourg train station.

Take rue Kuhn and you’ll come to quai Kléber, where the former synagogue burnt down. Period photographs commemorate the site.

The site has been named Allée des Justes (Alley of the Righteous), in memory of the courageous people who saved Jews during the Shoah. It was inaugurated on 22 July 2012 by Roland Ries (Senator and Mayor of Strasbourg).

Follow the quay to the left, until you reach rue du Général de Castelnau and that of his colleague General Rapp.

Rue Sellénick and the surrounding area is a small shtetl with schools, cultural venues such as the Cédrat bookshop and kosher restaurants.

Just a couple of hundred metres down the rue Strauss Durkheim, you’ll come across the Synagogue de la Paix, next to which is the Place Jean Kahn.

The Avenue de la Paix Simone Veil was named in tribute to the first President of the European Parliament, whose appointment, and above all her commitment to women’s rights and remembrance, symbolises the will and reality of peace in Europe since the end of the Second World War.

The avenue leads to the beautiful Place de la République (where the ancient Jewish cemetery used to be), surrounded by the Palais du Rhin, the University Library and the National Theatre.

Next to the National Theatre, the Passerelle des Juifs (Footbridge of the Jews) leads to the Quai Lezay Marnesia.

Take the Rue du Parchemin, which continues into the Rue des Juifs and where you will discover the old mikveh. Visits to the mikveh, like those to the synagogue, should be organised in conjunction with Jewish institutions.

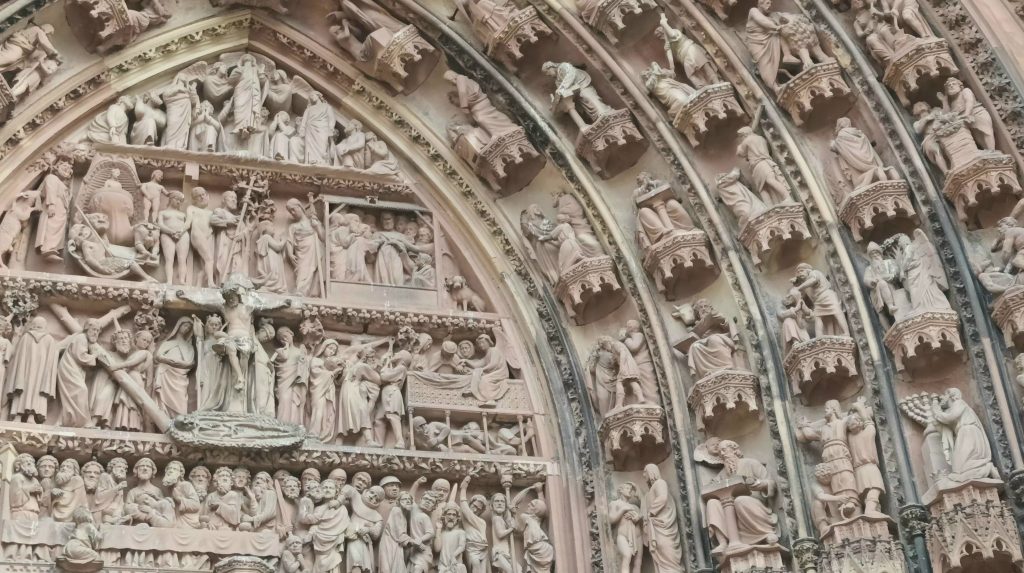

At the end of this street, opposite the former Kammerzell house, you will come across Strasbourg’s magnificent cathedral.

With its sculptures and its famous clock. A clock that, with all its references and inspirations, will take you on a journey through time and space.

She will also tell you that it’s time to round off this wonderful visit by visiting the Musée de l’œuvre-Notre-Dame, just down the road, and the Musée Alsacien (Alsatian Museum), a 5-minute walk away across the Pont du Corbeau.

This astonishing museum of regional arts and traditions lets you discover the diversity of this experience and its representations over the centuries. In particular, the ingenuity of the Alsatians in coping with the harsh winters and their early ecological awareness! There are also the various pieces of furniture made from fir wood, and the glassmakers of Meisenthal who invented Christmas decorations on fir trees, replacing the apples and walnuts usually used for this type of decoration when there were food shortages. Not forgetting local ceramics and the evolution of its iconic costumes.

Alsace’s ancient religious traditions are presented in rooms dedicated to Catholicism, Protestantism and Judaism.

But they are also presented at different times, as in Room 9, where the objects used for circumcision are on display.

Room 10 has a map showing the former presence of religions in Alsace. Then you enter the rooms dedicated specifically to each of the three religions. Many Jewish objects of worship are on display.

There is also a prayer board in Hebrew and French for Napoleon III.

And above all, as a link between the past and the future, the tribute to the Guardians of the Sites, the courageous people who fought to preserve Alsatian Jewish cultural heritage in the villages of the region, such as Habsheim, Hagenthal, Mommenheim, Muttersholtz, Westhoffen and Zellwiller, presented in this room. The Jewish oratory is located just beyond in room 15.

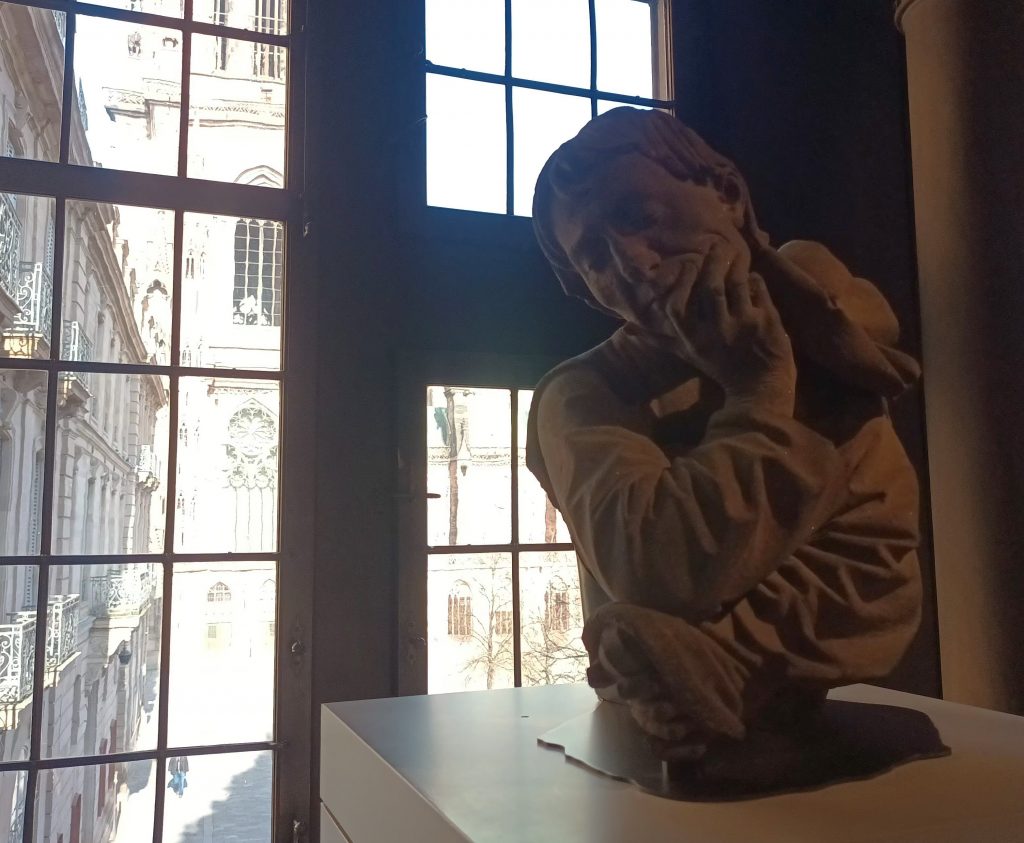

We had the pleasure and honor to visit the Museum of l’Oeuvre Notre-Dame with Jean-Pierre Lambert, President of the Society for the History of the Israelites of Alsace and Lorraine and one of the members of the Alsatian team behind the European Days of Jewish Culture and Heritage.

Jguideeurope: How was this museum created?

Jean-Pierre Lambert: The Foundation of l’Oeuvre Notre-Dame dates back to 1224, when it was responsible for the construction and restoration of Strasbourg’s cathedral. After the bishop had been defeated at Hausbergen and had definitively lost all temporal power over the city, since 1262 it has depended exclusively on the municipal authorities of the Free City of Strasbourg. The Foundation had its own sculpture workshops, as well as an architecture department and employed historians. In 1459, it became the Supreme Lodge of the Holy Roman Empire. Closer to home, it is the driving force behind a group of 18 cathedral workshops from 5 European countries, which will be included on UNESCO’s World Intangible Heritage List in 2020.

Since its creation, the charity has accumulated documents, replaced statues and other artefacts from the cathedral. It has also received countless donations and bequests from the faithful, religious art objects, not always related to the cathedral, such as forests or buildings. The OND conserves and exhibits all kinds of objects, most of them medieval: numerous Jewish tombstones from Strasbourg’s first cemetery, as well as statues, stained glass windows, paintings and tapestries from all over Alsace. To preserve and display the jewels in its collection, the OND has a magnificent complex of medieval and Renaissance houses opposite the cathedral, all of which have been added on top of each other, making for a highly original and interesting tour, passing through doorways and staircases that give a labyrinthine feel to this journey through time. Along the way, you can still admire the operative masons’ meeting room.

Some of the exhibits on display bear witness to the way in which Jews were viewed by the church, providing a better understanding of a complex relationship that is often caricatured to the extreme. It is also possible to do this research by visiting the cathedral, but it is more difficult because the evidence is less visible and the original statues and stained-glass windows have often been replaced by copies, or worst by 19th-century recreations of statues destroyed during the Revolution, which fortunately are less frequent than at Notre-Dame de Paris.

Was this view of the Jews positive or negative in the Middle Ages?

It was both. Exactly what we find in the Cathedral. It’s the same message, combining closeness and knowledge of the other with an often gentle but real demonisation.

Let’s take a few examples: in the first room of the OND, you can see a Romanesque capital where Jews with slightly deformed faces stand side by side with bats. This is a rare representation. For Francis Salet, the bat is the image of those who, like the Jews, are ignorant and refuse to see the truths of the Christian faith. This capital, which is in a rather poor state of repair, is probably a model (forgotten by its owner) of a similar capital carved in OND used during the restoration of the church at Sigolsheim. Some people have thought that these are two originals, and have deduced that this rare representation is common!

A little further on, a stained-glass window depicts Moses presenting Jews, recognisable by their pointed hats, with the bronze snake from Genesis coiled on a tau, resembling a caduceus. But we soon discover that the Jews are crossing their hands, in the manner of a praying Christian. This representation was very common in the Middle Ages and signifies that Moses, having seen the light, is himself asking the Jewish people to convert, which those present accept. According to Saint Paul, this conversion is the sine qua non for the return of the Messiah and therefore for the Parousia. For some, it had to be preceded by the return of the Jewish people to their homeland. This explains the unconditional support for Israel of American evangelical Protestants. The original statues of the Church and the Synagogue, perhaps the most famous medieval statues in the world, are also on display at the OND. To understand the scene, you need to go and see their copies, on the south portal of the cathedral. The synagogue, frail, very beautiful and swaying, is attracted to Christ and Solomon, his equal in wisdom and predecessor, but at the same time turns away from them. She is like the bride in the Song of Songs, willing and unwilling. Will Solomon be able to convince her? The fate of the world seems to depend on it.

Can you give us other examples of this complexity?

Yes, of course. Let’s take a scene that is very often depicted: the sacrifice of Isaac. For a Christian, this sacrifice is the first attempt to save the world by sacrificing a righteous person. It was a failure, because the sacrifice was unfulfilled. Christ had to die before humanity could be saved. I much prefer the Jewish interpretation, which says that by saving Isaac, the angel showed that the sacrifice of a human being is unacceptable.

A small stained-glass window, left over from a work by the great Pierre Hemmel d’Andlau (circa 1450), shows Jesus going to Limbo to pick up Moses and Elijah, who fold their hands as a sign of conversion. This well-known legend comes from an apocrypha. In one corner, a devil is discreetly depicted, along with an inferno. This work reminds us that the Sheol of the Jews, confused with limbo, was often interpreted as hell by Christians, especially in the Middle Ages.

I would like to end with two superb and comforting works. At the OND there is a marvellously sculpted ensemble representing the circumcision of Jesus. Everything is there, including the bottle of talcum powder. The circumciser has put on his glasses. His prayer shawl has become a kind of scarf, held by his two bent elbows: it won’t get in his way. The high priest has celebrated too much, and his face, a little heavy, is also too red.

In the cathedral, in the lower stained-glass windows on the south side, to the west, Jesus is being laid in the tomb by Joseph of Arimathea and Nicodemus, who are very focused. But both are wearing the large conical hat that identifies Jews, which is very rare (a similar representation exists in Fribourg, Switzerland). Jesus was born and died a Jew…

What are the oldest objects attesting to the Jewish presence in Strasbourg and Alsace?

In Strasbourg, of course, there’s the medieval mikveh, which is of impressive size, but also the tombstones on display at the OND and the Historical Museum. Rouffach is also home to France’s only fully preserved medieval synagogue (1290), which cannot be visited at present, and there are several inscriptions attesting to the presence of synagogues in Obernai, Molsheim and Haguenau. However, there are fewer traces of Jewish presence after the 16th century.

Are local authorities involved in sharing Strasbourg’s Jewish cultural heritage?

On the whole, yes. A number of institutions in Strasbourg offer Jewish tours, including the Tourist Office, another of the city’s tourist offices in which I played a part, the Departmental Tourist Development Agency and others. The mikveh has recently been restored, with a much more flexible access system. A memorial garden was created very recently on the site of the consistory synagogue, which was destroyed by the Nazis. This formalisation shows that the local political authorities clearly have the objective of better highlighting the Jewish presence in Strasbourg. This will cover not only the medieval period, but also the entire Jewish history of Alsace and Strasbourg, which has been largely uninterrupted from 1140 to the present day.

A joint research programme on Jewish heritage has been launched by the Regional Directorate for Cultural Action (DRAC) and the regional inventory service. The national education system, through the intermediary of the rector, is preparing a programme to highlight Judaism, which is necessary in these times, and Alsatian universities are currently attracting more students interested in Jewish history. It should also be noted that it was in Strasbourg in 1996, with the support of the Bas-Rhin department at the time, that the ‘Open Doors to Jewish Heritage’ operation was launched (in 1996, 5,000 participants in 15 locations in the Bas-Rhin), which over time became the ‘European Day of Jewish Culture and Heritage’ (in 2022, almost 150,000 visitors, 29 participating countries, 860 activities in Europe). Last but not least, plans are underway to list Alsace’s collection of synagogues, the most extensive in Europe, as a World Heritage Site…

You can continue your visit in a variety of ways, depending on what you fancy and what this beautiful city has to offer within a few hundred metres. In particular, the Place Gutenberg, named after the famous printer.

The museums of Fine Arts, Archaeology, the City of Strasbourg or the Palais Rohan. Shops, restaurants and seasonal attractions… or the simple pleasure of relaxing on a terrace on the banks of the River Ill or strolling through the historic district of Petite France

and over the Vauban Bridge, hesitating over which bank to return to and prolong the pleasure of being in Strasbourg.

This small town lying in the shadow of an old abbey once had a very active community. You can still see the birthplaces of its two famous Jewish sons: the painter Alphonse Lévy , who was born here in 1843 and died in Algiers in 1918 and whose work bore witness to Alsace’s rural communities; and Albert Kahn , born in 1860, who died in Boulogne-sur-Seine in 1940.

The synagogue , built in 1822 and now unused, can still be seen. Take rue Neuve out of the village. Once in the forest, you will come to a small cemetery built in 1799. Interestingly, though the engravings on the tombstones are in Hebrew, there are also brief annotations in the local language on the back. While these are sometimes in German on the oldest stones, they are all in French beginning from the annexation of Alsace by the Germans in 1870.

The Museum of Alsatian Heritage and Judaism is housed in a fine timbered building dating from 1590 that was home to Jewish families without interruption from 1680 to 1922. Here you can see the mikvah from 1710 and, in the kitchen, a flat oven that may have been used to cook matzhohs for Passover. The collection of Jewish cultural objects gives a idea of the size of the community in those days. Note in particular a remarkable curtain for the Holy Ark (1857) from the synagogue at Quatzenheim.

In 2019, the museum received five original lithographs by the great local painter Alphonse Lévy. In May 2025, it dedicated a space to philanthropist Albert Kahn, a native of Marmoutier.

The Mizmor Chir trio gave a concert in October 2025 in the ancient synagogue of Marmoutier.

The Jewish presence in Bouxwiller seems to date from the 14th century. The princes of Hanau-Lichtenberg adopted Protestantism and were open-minded towards Judaism and its presence during the Reformation, especially in their capital Bouxwiller. They authorized a yeshiva founded by the patron Seligmann Puttlingen and directed by the Chief Rabbi Wolf bar Jacob. Thus, the number of Jewish families living in Bouxwiller was estimated at 36 in 1725. A small gradual increase followed.

A synagogue was built in the 18th century and replaced in 1842 by a larger synagogue, allowing the 353 Jews living in the town to find an adequate place to pray. Destroyed during the Holocaust, only an oratory was built there after the war and used until 1956 by the community which had lost many members and whose surviving members were aging.

The building has since been transformed into the Judeo-Alsatian Museum set out to present the life and history of Judaism in the countryside. There are no rich collections here, therefore, but a sequence of displays with re-creations and moving, ritual objects reflecting ordinary life and the major moments of Jewish life in Alsace. The building’s empty interior -the Nazis converted it into a factory- allows for a unique architectural experience. It contains a sequence of ramps and platforms that permit visitors to share in the traditions of the Jewish hawkers and wholesale butchers of the countryside. Mannequins with heads in twisted iron and ceramic models also bring to life these lost communities.

The museum hosts cultural events, as was the case in 2021 during the festival of Jewish music with the arrival of the duo Place Klezmer.

In 2023, the museum celebrated its 25th anniversary, with events including a tribute to Gilbert Weil, its founder.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr et dna.fr

The Jewish presence in Pfaffenhoffen probably dates from the beginning of the 14th century.

In 1683, the first synagogue in Pfaffenhoffen was built. However, it was destroyed shortly afterwards. This did not prevent the Jewish community from growing from three families at the turn of the 18th century to sixteen on the eve of the French Revolution. Following the three major wars and the rural exodus, it gradually diminished. Thus, there were only 69 Jews left in Pfaffenhoffen in 1936, and half of them after the Shoah.

The small village synagogue from 1791, with its modest façade, is without doubt the most moving historical place in Alsace.

Here, no ostentatious gilding or gleaming marble, but a simple synagogue with white walls and, on the first floor, its kahlstube, its kitchen, and its room for the shnorrer of passage. Near the entrance, you will notice a stone fountain that is even older than the synagogue itself: its Hebrew date is 1744.

On the upper floor, the prayer hall has kept its wooden benches, its beautiful frame of the holy ark, decorated with the lions of Judah and the vines of Alsace. In the bull’s eye, you will pay attention to the blue and white windows which, according to the Talmud, allow to determine the morning time of the prayer when, at daybreak, one manages to distinguish the two colors. This elementary way of marking time disappeared in the 19th century with the appearance of the pocket watch. In 2000, the synagogue was transformed into a museum.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr

Traveling rabbis served the small local communities, made up of several or more families (some ten at Evreux and Lisieux, around two hundred at Le Havre). The only sizable community structure, a small synagogue , was built by the Jews themselves after the liberation of France.

A new exhibition dedicated to the Holocaust was inaugurated on 1 April 2025 at the Caen Memorial. It aims to break with traditional museum practices regarding the memory of the Holocaust. It also presents the lives of Jewish communities before the Holocaust.

Sources: Times of Israel

In medieval times, there was an intense intellectual life around the synagogue’s Talmudic school in what was called “Le Clos aux Juifs” (the Jews’ Enclosure). Contrary to what its name suggests, the enclosure in question was never a closed space. There were Jews living elsewhere in the town and Christians living in the Clos. All this disappeared in 1306, when the community was expelled. After that, only very few were able to identify Rouen as the brilliant and lively “Rodom” described in ancient texts.

In 1976, repaving work in the courtyard of the Palais de Justice brought to light an extraordinary archaeological find: the walls of an eleventh-century Jewish building, the oldest Jewish monument in Western Europe! Since then, it has been the object of endless debate between specialists. The home of a wealthy merchant, a Talmudic school, a synagogue- what exactly was it? The following fragment from the divine words spoken to Solomon (1 Kings 9:8) were clumsily engraved into the walls three times: “this house, which is high”. No doubt they were hastily inscribed at the moment of the expulsion.

At their base two small columns, a stone dragon and, facing it, a wild beast, placed strangely back to front, with two bodies and only one head (a typical Roman sculpture), are probably an evocation of Psalm 91 (verse 13): “The young lion and the dragon shalt thou trample under feet”. A stone spiral staircase leads to a low room with narrow windows that may have been used to store manuscripts. Following some works, the place can once again be accessed via organized tours of the Maison Sublime.

An ancient synagogue has been present in Rouen from at least the 16th century. But it was then destroyed. Todays’ modern synagogue was built in 1950 by the architect François Herr. It consists of a building and a porch, and most importantly, it is decorated by beautiful stained glass.

Anti-Semitic tags were discovered on the synagogue in Rouen and the rabbi’s residence in January 2025. Just a few months after the attack on the synagogue by a terrorist attempting to set it on fire, a policeman saved the place thanks to his swift intervention.

Brussels, the capital of the European institutions, a celebratory place appreciated by tourists, but also a city immortalised by the numerous comic strips born there, remains an amazing city. The cohabitation of a magnificent old town, office towers, and numerous bars where one finds the warm Belgian spirit. But also a worrying radicalism and its drifts, as illustrated by the terrorist attack on the Jewish Museum of Belgium in 2014.

The Jewish presence in Brussels dates back to at least the 13th century. The first written evidence of this presence is represented by a Torah scroll dating from 1310. Following the Black Death and the anti-Semitic accusations of the time, the Jews were singled out and massacred in the middle of the 14th century. Their resettlement was very short-lived, as the Jews suffered another pogrom in 1370, based on false accusations of desecration of hosts. Consequently, they could only return during the Spanish rule of the region. Only a few Marrano families lived there in the meantime.

The Jewish renaissance in Brussels took place under Austrian rule in the early 18th century. Most of the Brussels Jews, about sixty in number, came from the Netherlands. The subsequent French and Dutch conquests did not hinder the resettlement of the Jews, who were allowed to settle freely. A sign of this development was the creation of the Jewish primary school in 1817 by Brussels intellectuals.

Following Belgium’s independence in 1830 and the 1831 Constitution guaranteeing freedom of worship, Brussels became the centre of the country’s Consistories. Eliakim Carmoly was the first Chief Rabbi of Belgium, elected in 1832. The community was then composed of Jews from the Netherlands, Germany, and then from Poland and Russia at the end of the century, following threats and pogroms in these countries.

The consistory system made it possible to establish requests for access to a place of worship, in order to mark the Jewish roots in Brussels at that time. At the beginning of the 19th century, houses, first in rue aux Choux, then in rue de la Blanchisserie, served as transitional places. A project for a synagogue in the rue de Berlaimont, inspired by the one in Frankfurt, came to fruition in 1832 when the Consistory presented it to the minister in charge of these matters. The synagogue was finally inaugurated on the Place de Bavière.

Due to the dilapidated state of the building in Bavaria Square and the rapid increase of the Jewish population in the 1830s, another location was considered. Real estate and geographical differences between the representatives of the Consistory and the local authorities delayed this project.

In 1868 the Consistory launched a competition for the design of a new synagogue. It was won by the architect Désiré De Keyser. After a long study of European synagogues, De Keyser’s proposal for a Romanesque synagogue was approved by the Consistory in 1873. This style of the Grande Synagogue de la Régence was a sign of the good integration of the Brussels Jews. Its location was in the old town.

The Jews, however, mainly lived in the working-class neighbourhoods next to the Midi station, in Anderlecht and Saint-Gilles. However, the good integration allowed them to gradually live in different parts of the city and the centrality of this synagogue seemed logical rather than to install it in a district far from the others.

The Regency Synagogue was inaugurated on 20 September 1878. The synagogue is in the Romanesque-Byzantine style, inspired by the synagogues of Lyon and Stockholm. On the outside, there are two turrets and in the centre of the building, the Tables of the Law. Around the rose window are engraved the names of the twelve tribes of Israel. The temple has a 25 m high nave. Twenty-five stained glass windows can also be admired.

On the eve of the Second World War, 30,000 Brussels Jews lived in the capital. Like other Western communities, this one was crossed by differences of appreciation, even of life between its various components: Westernised for a long time for some and other more recent migrations. The latter were more traditional or, conversely, inspired by the Eastern European revolutions, marked in particular by the development and success to this day of the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement. The main sector of activity was the textile industry.

Many Jews enlisted in the Belgian army during the First World War, whether as soldiers or officers, such as General Louis Bernheim, Captain Ernest Wiener or Captain Robert Goldschmidt. Another strong symbol of this courage is that in 1936, 200 Belgian Jews enlisted in the International Brigades during the Spanish War.

The demographic concentration unfortunately facilitated the work of the Nazis during their roundups. At the intersection of rue Émile Carpentier and rue des Goujons, you will find the National Monument to the Jewish Martyrs of Belgium. The names of 23838 victims are engraved in the stone. The square on which its stands has been renamed Square des Martyrs Juifs (Square of the Jewish Martyrs).

In the aftermath of the war, the Jewish population of Brussels declined, with the number of victims of the Shoah, but also departures to North America and Israel. The city received several thousand Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe. In the early 1960s, following the independence of the Congo, Jews from this former Belgian colony also settled in Belgium, mainly in Brussels.

Reflecting the plurality of Jewish movements in Brussels, the David Susskind Secular Community Center (CCLJ) remains one of the major Jewish institutions today. It was founded in 1959 by survivors of the Shoah who wanted to transmit a Jewish identity that was distinct from religious structures. Numerous cultural events are organised there, in a spirit of openness and sharing. But also educational programmes to fight against racism and the resurgence of anti-Semitism. In particular, by raising public awareness of the other genocides of the last century, in Armenia and Rwanda. The CCLJ is known for its magazine “Regards”, founded in 1965 by Victor Cygelman, Albert Szyper, Jojo Lewkowicz and above all David Susskind, a great figure of the Belgian left and a militant of the Israeli-Arab rapprochement.

The House of Jewish Culture also organises a wide range of events, providing a convivial space for conversation, creation, renewal and the transmission of Jewish cultural memory. These include conferences, studies, exhibitions, concerts and workshops. There are also Yiddish and Judeo-Spanish language courses. Not forgetting its famous Jewish music festival every year. You can also sign up for their themed tours of Brussels districts.

As a sign of the diversity of the Brussels Jewish community, new synagogues were inaugurated after the war in different districts. Among these were the synagogues in the popular district of Schaerbeek. Many Jews lived there since the interwar period, praying in small oratories. The Sephardic synagogue Simon and Lina Haim was inaugurated in 1970, at 47 rue des Pavillons, welcoming people from North Africa and the former Rhodes communities. An Orthodox synagogue was inaugurated in 1979, located at 126-128 rue Rogier. Unfortunately, both synagogues were put up for sale in 2016.

English-speaking Jews, most of them working in the city’s European institutions, form a fifth of Belgium’s Jewish community. They attend Shabbat services with Liberal French-speaking Jews. The Beth Hillel Synagogue is strongly attended during Jewish festivals. The good integration of the Jews in Brussels, but also the antisemitic attacks, motivated people to move to safer neighbourhoods, such as in the south of the city in Uccle, favouring security over square metres. Thus, the The Sephardic Synagogue Etz-Hayim , which is small but very congenial, was founded in 1992. The Dieweg cemetery is located in Uccle and is home to a Jewish cemetery.

Directed by Barbara Cuglietta, the Jewish Museum of Belgium has a large collection of ancient and modern documents illustrating Jewish life. The Jewish Museum of Belgium was opened in 1990 on Avenue de Stalingrad. A first unsuccessful attempt in this direction was made in 1932 by Daniel Van Damme, curator of the Erasmus Museum in Anderlecht. In 1938, the Queen’s Gallery presented the first exhibition dedicated to the Jews of Belgium, organised by Dode Trocki.

The project was relaunched in 1979, when a proposal was made to Jean Bloch, President of the Consistory, to organise an exhibition on the art and history of Belgian Judaism, within the framework of the 150 years of the country’s independence. Steps were therefore taken to make this project permanent and to find a place that would present this history to the general public. Temporary premises were found at 74 avenue de Stalingrad, where the first exhibition was inaugurated on 25 October 1990.

In 2005, the museum moved to rue des Minimes, in a place more favourable to the reception of the public. A number of objects were acquired through sponsorship, notably from the Jacob Salik Fund. The museum has various archives and a library, having integrated the collections of the Kahlenberg, Misrahi, Souweine, Lévy, Cuckier, Schneebalg-Perelman, Galler-Kozlowitz, Broder, Jospa, Albert, Schnek, Bernheim and Lounsky-Katz families. Philippe Blondin has been the president of the Jewish Museum of Belgium since 2007.

Work is due to be carried out soon to enlarge the spaces and modernise the presentation, particularly through digital tools. The museum is scheduled to reopen in 2028. Nevertheless, in the meantime, here is what the visit to the museum, which we visited again in 2023, was like.

At the beginning of the permanent exhibition dedicated to the history of the Jews in Belgium, we see historical photos, of royal visits but also of important donors such as Baron Lambert who financed the opening of a maternity hospital in 1932. This great family created the Banque Bruxelles Lambert and helped many charitable, social and cultural works, from its founders at the beginning of the 19th century to its descendants Philippe and Marion Lambert.

The first rooms allow the public to familiarise themselves with Jewish customs thanks to these old photographs. But also artistic works such as the hundreds of wine glasses hanging from the ceiling like chandeliers, witnessing all these moments of celebration. The museum shows the story of the Kilimnik family, Jews from Podolia who settled in Molenbeek in 1921.

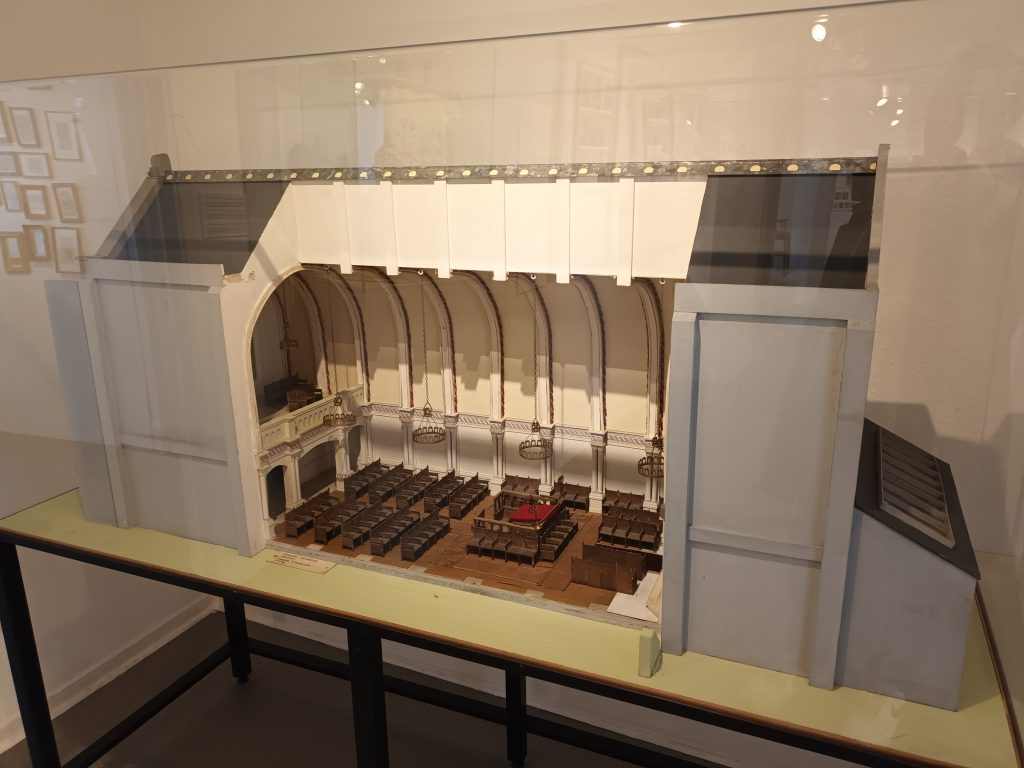

Located in Brussels, the museum honours Jewish life in the capital, the large community of Antwerp, but also in other cities, telling the story of the communities of Liège, Ghent, Namur, Ostend and Arlon, with photos. Stories illustrated for example with an old postcard of the synagogue of Arlon or its beautiful parokhet, offered by the ladies of the community in 1874. Beautiful photos of old synagogues in the country are presented, as well as a model of the Portuguese synagogue in Antwerp.

The Jewish holidays are explained and illustrated on the walls of the museum, with many objects. Not forgetting the magnificent Megilat Esther by the artist Gérard Garouste and the Purim mosaic by Eddy Zucker. Holidays based on historical resistance and sometimes celebrated in a spirit of resistance, such as this menorah made by Alexandre Gourary in the Dossin barracks detention camp.

On the way up the stairs there is a moving photograph of Orthodox Jews in a park in Antwerp, walking their children on sledges. The stairs lead to the first floor, where the bust of Baroness Clara de Hirsch, a great Belgian philanthropist, stands at the entrance to two rooms.

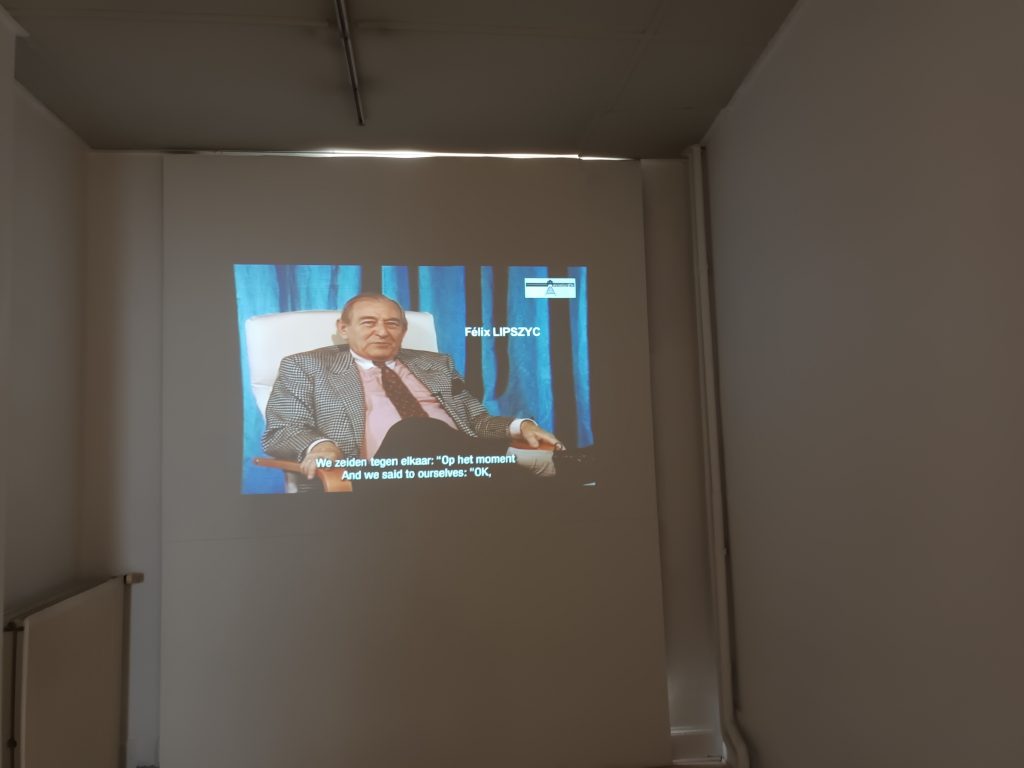

The first room presents the period of the Shoah in Belgium. The history of the persecution of the Jews is described above two suitcases of deportees. Photos, yellow stars and administrative documents are displayed. Then there is a wall with 227 photos of the 236 deportees who escaped from a train, the 20th convoy, which left Mechelen for Auschwitz in April 1943. A documentary by Sarah Timperman and Stéphanie Perrin is shown at the back of the room and tells the story of the heroic rescue of the 20th convoy, with the help of testimonies by Félix Lipszyc, Abraham de Groot, Simon Gronowski and Robert Maistriau.

The second room houses works by contemporary Jewish artists such as Arié Mandelbaum, Sarah Kaliski, Kurt Lewy, Felix Nussbaum, Arno Stern and Kurt Peiser. Temporary exhibitions are also presented, such as the one recently dedicated to Moroccan women on the floor above, or at the entrance of the museum with photos by Jo Struyven and Luc Tuymans of the places where the deportees of the 20th convoy escaped.

In the courtyard of the museum, there is a plaque in homage to the victims of the terrorist attack of 24 May 2014, in which four people were murdered: Alexandre Strens (an employee of the museum). Dominique Sabrier (a volunteer at the museum) Emmanuel and Myriam Riva (an israeli couple on vacation). In may 2024, a ceremony commemorated the 10 years since the attack.

In Brussels, as in many European cities, the exploitation of the 7 October pogrom by various forms of anti-Semitism has manifested itself in insults, threats and attacks. Extreme hostility towards Jews and any condemnation of new forms of anti-Semitism is particularly noticeable in certain universities…

If all roads lead to Rome, one of the most beautiful roads in Brussels leads to Paris. Near the allée Chantal Akerman, in the 20th arrondissement of Paris, one of the greatest filmmakers of all time lived from the age of 18. “My daughter from Ménilmontant”, as she is nicknamed by her mother Natalia in the book “A Family in Brussels”, is a dialogue of memories, stories and silences. Brussels and Paris devoted a major exhibition to her in 2024-5, and her films are still regularly shown in cinemas around the world.

Like Albert Cohen, she is the author of masterpieces in many different genres. The only difference, perhaps, is that she didn’t need to make “The Film of My Mother” when it was too late, since Natalia Akerman has been in the limelight right from the start of her daughter’s work.

An Auschwitz survivor, Natalia doesn’t talk about it, torn between the imminent need to hold on and rebuild and the Jewish resilience that consists of promising a better dawn for the next generation. All the while, she passes on her strength and dignity to her daughters Chantal and Sylviane.

From her father Jacob, they inherit humour, hard work and a willingness to dance through life and out of trouble. Jacob Akerman is a shopkeeper, owning a clothing factory in the Triangle district and a shop in the Toison d’Or gallery.

As for Brussels, it shares with the two young women born in the aftermath of the war, its bon vivant Belgian spirit, with its cartoon characters, glasses and stories all rounded off to facilitate boats overflowing with pleasure, inspiring in its own way so many stories with cheerfully spilled beers.

Chantal’s Polish maternal great-grandfather was on his way to the United States, trying to reach the port of Antwerp to embark. But like so many Jews, he realised just how happy life could be for a Jew in Belgium.

Chantal Akerman was born in Brussels in 1950. At the age of 15, she went to see Jean-Luc Godard’s “Pierrot le fou” at the cinema with her friend and future producer Marilyn Watelet, amused by the film’s title. It was a revelation and the birth of her ambition.

At the age of 18, she directed the short film “Saute ma ville”, earning the support of André Delvaux and Eric de Kuyper. The story of a teenager who locks herself in the kitchen and acts in increasingly incoherent ways, throwing everything away and shining her shoes and then her legs next to a Manischewitz box.

Chantal moved to Paris after the shoot, hoping to find inspiration there, which never left her in Paris, New York, Brussels, Tel Aviv, Germany, Eastern Europe and even on the Mexican-American border.

At the age of 23, she directed “Je, tu, il, elle” (I, you, he, she) with Niels Arestrup and Claire Wauthion, a tale of anxiety, wandering and the reunion of operatic bodies. Two years later, Chantal entered the big leagues once and for all with “Jeanne Dilman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles”. Delphine Seyrig leads an ultra-ordered life, covering up her silences and wounds, bringing up her son alone. A life without pleasure, until something unexpected happens. In 2022, this address and more precisely this work was voted best film of all time in the ten-yearly rankings drawn up by “Sight and Sound”, the magazine of the British Film Institute.

In “Pierrot le fou”, Jean-Paul Belmondo asks Samuel Fuller to define cinema. The director replies that it was an emotional battlefield. Perhaps this is why Chantal Akerman is one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. Her camera presents love and humour, songs and silences, deep thoughts and nagging worries through a gaze that is both mischievous and gentle. Ahead of her time, ahead of our time too, between the reconstruction of a generation and their children’s quest for pleasure and self-assertion, who fear the return of the dark ages. Sylviane Akerman, Chantal’s sister, now preserves her memory, notably through a foundation.

In 2023, a fresco in the likeness of Jeanne Dielman, the main character in the film ‘Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles’ was unveiled in Brussels as a tribute Chantal Akerman. The fresco was created by the artist Alba Fabre Sacristán and appears on the façade of a house on the corner of quai aux Barques and rue Saint-André, close to quai du Commerce.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, Politique et Religion : le Consistoire Central de Belgique au XIXe siècle, Les Juifs de Belgique : de l’immigration au génocide (1925-1945) MuseOn, RTBF

Despite the devastations of the Second World War and the aesthetic shortcomings of post-war reconstruction, Amsterdam offers the visitor a Jewish patrimony of extraordinary richness that is concentrated, for the most part, in its memorials.

The former Jewish quarter, the Jodenbuurt, is yours to discover along the streets and canals in the southeast of the city. It is easy to imagine the period when the area was home to a population that had grown from several hundred inhabitants at the end of the sixteenth century to some 100 000 in 1940. Among the attractions are exceptional museums, synagogues, and period homes of famous residents (Rembrandt, de Pinto) preserved in their original state. Diamond-cutting workshops, guild houses, and religious monuments are also among the numerous traces of 350 years of Jewish presence.

If Amsterdam has brought a lot to the Jews, the reverse also holds true. The city has absorbed many typically Jewish characteristics into its language, cuisine, and sense of humor. Hence, mazel (good luck) and meshuga (crazy) can still be heard in the local dialect; likewise, the Netherlands adopted pickled herrings and onions, sausages and fromage blanc.

The Jewish Historical Museum alone requires nearly a half day. Since 1987, the museum has been the heart of a cultural complex made up of four synagogues active until 1943 and subsequently sold to the municipality in 1955. The museum depicts Jewish customs, the fundamentals of the Jewish religion and Zionism, as well as the way of life of Dutch Sephardim and Ashkenazim in past centuries. In 1943 the collection of the synagogue complex was taken to Offenbach in Germany. Less than 20% of the stolen goods were recovered by the Dutch government after the war. With the aid of glass and metal installations, the displays of these four synagogues recall the massacre of the majority of Amsterdam’s Jewish inhabitants, a tragedy not only for the Jews but for the city as well.

The Grand Synagogue was consecrated in March 1671 by the Ashkenazic community, which had renounced the claims of the false Messiah Sabbataï Zevi. Today display cases containing silver ritual objects occupy the former location of the bimah. The ark of the Covenant, made completely of marble, has been restored, as have the galleries reserved for men and women and the mikvah. Space demands led to the construction of the three other synagogues nearby: Obbene Sjoel (1685), Dritt Sjoel (1700), and the New Synagogue (1752). In addition to religious objects and works of art, the museum also displays documents retracing the history of the two Jewish communities and the people who influenced them. One such figure gives the square its name: Jonas Daniel Meijer (1780-1834), a lawyer and highly-ranking civil servant who attempted to improve the welfare of underprivileged Jews in Amsterdam.

After your visit to the museum, explore the ancient Jewish quarter as you read what follows, much of which has been mentioned in connection with the museum. Note that the Museum organizes guided tour of Jewish Amsterdam.

President of the High Court in 1939, Liuis Ernest Visser actively defended the Jews during the Nazi occupation. After you cross the square that bears his name, Mr. Visserplein , you come upon the Moses and Aaron Catholic Church . The tiny statues that once decorated the facade and gave the church its name are presently found on the back wall. On your left, enter Jodenbreestraat . From the eighteenth century to the Second World War, this street was the principal artery in the Jewish quarter. In 1965, the northern part was destroyed and the street rerouted.