Jesi is an ancient Roman city, known for its medieval walled old town. Its squares, churches, and other buildings bear witness to the passage of time.

The Jewish presence is mentioned in documents from 1431. A certain Benedetto and the Vivanti family were important figures in Jesi’s financial life, as Jews were initially restricted to these professions. In 1459, Jewish residents succeeded in obtaining equal citizenship rights with the general population, allowing them to buy land. It was at this time that the community was able to obtain a plot of land to bury the dead.

The location of this ancient cemetery seems to have been near the Via Piccitu, where the stele of Rabbi Moses, which is said to date from the 16th century, was found in 1928. It is currently on display at the Jesi Civic Museum . The museum has two other text sculptures. The first one in Latin, describing the situation of the Jews under Pharaoh. The second in Hebrew.

The professional activities of the Jews of Jesi diversified in the 16th century, especially in the silk, metal, wine, and medical sectors. The first reference to a synagogue is in a document of 1532, which tells of a dispute that took place there among the faithful. Ten years later, the Jews gradually left the city following a papal bull. Only a handful of Jews were allowed to resettle over the centuries.

Sources : Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni

Fermo is a very old city, built in pre-Roman times, probably 3000 years ago. Its many palaces, cultural and religious sites still bear witness to this antiquity. The first document mentioning the Jewish presence dates from 1229, indicating the appointment of Jacobus Judei to the first municipal council.

The famous Italian poet Immanuel da Roma (1261-1328), nicknamed Manoello, lived in Fermo until the end of his life. Inspired by various sources, both Jewish and Christian, he left an important work of poetry, but also of exegesis and linguistics.

During this period, Jews distinguished themselves in many areas of local active and intellectual life. A symbol of this openness was Elia di Sabbato, surgeon to the papal authorities from 1407. He was ennobled by the local authorities of Fermo. A street now bears his name.

Nevertheless, other public figures tried to reverse this course, demanding the limitation of the rights granted to the Jews. The situation remained quite positive, however, as the Jews diversified their activities in the 15th century, especially in the leather, textile and cosmetics sectors.

The ancient giudecca was located near the present Corso Cavour . A synagogue was located there, according to ancient documents.

A ghetto was established in 1566 around the present Via Bergamasca , behind the Torre Matteucci. Buildings from this period, as well as a former synagogue, are still located in Vicolo Silvestri . Due to a relative deterioration of the situation, the Jews gradually left Fermo to settle in Pesaro, Senigallia and Ancona.

Sources : Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni

Castelleone di Suasa, a very old town built on a hill with a Roman amphitheatre and many places of interest to archaeologists, welcomed Jews at the beginning of the 17th century. The main purpose was to take part exclusively in the financial activities forbidden by the religious authorities to non-Jews.

In 1738, the Jewish population consisted of thirty-five families living in the vicinity of the castle, in what was known as the vicoli del Ghetto. Today it can be reached via the Via delle Scuole .

The Jewish population disappeared at the end of the 18th century, a little later than in many other towns in the region, thanks in part to the protection granted by Duchess Livia.

Sources : Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni

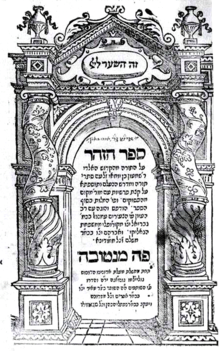

Cagli is also known for its theatre and, above all, its ancient printing works, one of the oldest in Italy, dating from 1475. The Jewish presence in Cagli dates back to the 14th century, as a document from 1400 attests.

They participated in the commercial development of the wool and leather industry, with Salomone di Sabato being particularly prominent in this. A synagogue seems to have been located on the ancient Via Impetrata and actual Via Fonte del Duomo. The Jewish quarter was located in this area. The community had a cemetery located between the city walls and the Bosso river.

Following a wave of discrimination, the Jews left the city in the 17th century, encouraged to settle in the ghettos of Senigallia, Pesaro and Urbino. In the middle of the 19th century, the Jewish community of Urbino asked Francesco Pucci, a native of Cagli, for an aron and a tevah for their synagogue.

The Archaeological museum of Cagli has works by Pucci, including an ivory table with a magen david. Jews bear this name, as is often the case with the city or the profession of origin. Among them is the artist Corrado Cagli, born in Ancona in 1910.

Forced to leave the country following the promulgation of the racial laws, he participated as a soldier in the liberation of Buchenwald. His post-war work bears witness to the horrors he encountered there.

Sources : Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni

The town still has many buildings showing architectural influences from many periods: Roman, medieval, renaissance, modern…

The Jewish presence in Ascoli Piceno is attested since 1297 when three Jews were allowed to settle there, as part of a consortium of twenty-two financiers. Documents seem to indicate that in the 14th century the Jews were not confined to certain areas. Professional activities were gradually diversified.

The community had a cemetery in the 15th century near Campo Parignano, but there is no trace of this place today due to the construction of houses in the area. A cemetery has been used by non-Christians since the 19th century.

An oratory was opened in 1515 in the neighbourhood of Sant’Emidio . The community grew at that time, especially with the arrival of Jews from Naples who were welcomed in the area. However, the situation deteriorated and the Jews had to live in a separate area between Via Enos d’Ascoli, Via Giudea and Rua David d’Ascoli . The latter is named after the doctor who published “Apologia Hebraeorum” to oppose discrimination against the Jews and was consequently imprisoned. They were forbidden to practice certain trades and were then expelled in 1569. Allowed to return, they were expelled again in 1678.

The Ascoli surname is borne by many Jews, probably in connection with the town of origin. Among them are Albert Abram Ascoli, a doctor who pioneered vaccination against tuberculosis, the linguist Graziadio Isaia Ascoli and General Ettore Ascoli, who died fighting Germany in 1943.

Sources: Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni and Encyclopaedia Judaica

Viareggio is a famous seaside town and an important cultural site. The Jewish presence is quite recent compared to other settlements in the area, dating mainly from the 20th century. About 50 Jewish families lived there in the 1930s.

An oratory was built in 1954 by the Procaccia family. It can accommodate about sixty people. Religious ceremonies are held there throughout the year. Tourists are also welcome by contacting the local community in advance, for obvious security and anti-Covid reasons.

Sources : Tuscany Jewish Itineraries by Dora Liscia Bemporad and Annamarcella Tedeschi Falco

The city depended on Florence for its expansion, which was possible mainly from the 19th century onwards, thanks to the growth of its agriculture and industry at that time. Its medieval and later palaces bear witness to the architectural and artistic wealth of Pistoia.

As in many cities in the region, Jews were first allowed to settle in order to practice banking. These were forbidden to the locals and the Jews were not allowed by the political authorities to practice other trades.

Thus, two Jews settled there in 1397 to open a loan bank. Others were able to settle there later. Rare historical documents from this period are kept in the State Archives of Pistoia. As in most cities in the region, the Jews of Pistoia were expelled in 1570 and forced to move to Florence and Siena. Nevertheless, some of them resettled there in 1641. The city had its own small ghetto at the beginning of the 18th century, in the area around Piazza dell’Ortaggio . A synagogue was probably located in this square.

Sources : Tuscany Jewish Itineraries by Dora Liscia Bemporad and Annamarcella Tedeschi Falco

Monte San Savino is a Roman town known for its medieval buildings, especially by the sculptor and architect Andrea Contucci, better known as Sansovino.

The Jewish presence in Monte San Savino dates from at least the beginning of the 15th century. Jewish banking families were prominent in the city at that time and contributed to the development of Monte San Savino. Recognition of this fact encouraged the city at the end of the 17th century to allow the settlement of several families who did not work in the same fields: agriculture, trade, leather work. This was followed by the opening of a synagogue (built from 1732) and a Jewish cemetery.

As a result of these developments, the town had 103 Jews in 1745. This stability lasted for another 50 years, as Jewish residents left the town following a wave of violence.

Traces of Jewish life remain in Monte San Savino. Starting with the ancient synagogue on Via Salomone Fiorentino , named after an illustrious member of the community, a businessman and man of letters of the late 18th century. Jews lived mainly in this area at the time, but not only there. Jewish graves can still be seen on a plot of land next to the Catholic cemetery. The Municipal Library has many documents that testify to this Jewish life.

Sources : Tuscany Jewish Itineraries by Dora Liscia Bemporad and Annamarcella Tedeschi Falco

An important town in the Middle Ages, especially following the victory of Montaperti and the establishment of a parliament in 1260, Empoli became a significant industrial centre, especially for glassmaking.

The Jewish presence dates back to at least the beginning of the 15th century, when they were allowed to work in the banking sector, most of them coming from the town of San Miniato.

A majority of them lived in the southern part of the street that connected the Arno Gate to the Siena Gate (later Piazza del Popolo). An area nicknamed Giudea . The ancient Jewish cemetery was probably located not far from there, taking the Via de Neri from the Piazza del Popolo.

An ancient tomb with Hebrew inscriptions is presented in the Pinacoteca di Sant’Andrea .

The Jews were expelled from the Florentine Republic in 1495 but were able to resettle in Empoli from 1514. About ten years later, a new migration of Jews took place, working mainly in the sale of woollens. Nevertheless, they were expelled again in 1570, most of them settling in the Florence ghetto.

The municipal archives have documents that attest to the ancient Jewish presence in Empoli. In particular a Babylonian Talmud.

Sources : Tuscany Jewish Itineraries by Dora Liscia Bemporad and Annamarcella Tedeschi Falco

Udine is an ancient Roman city, later also known for its university, palaces and museums. The Jewish presence dates back to 1299.

The community grew, but the first restrictive measures were imposed in the 1420s, especially on their residence rights. Although expelled once in 1462, some Jews were still able to work in the city.

The Jewish cemetery dates from the beginning of the 15th century when the land was bought by members of the community. The final expulsion was decided in 1556. It was not until the arrival of the French at the end of the 18th century that the Jews could return to Udine.

In the 1840s, the Jewish community consisted of about 100 people. They had a synagogue, located in the present Porta Manin . At that time they acquired a new cemetery , in the village of San Vito, which was used until the present day.

The Jewish population gradually decreased from 112 in 1840 to 88 in 1931. The Jewish community of Udine is nowadays attached to that of Trieste.

Sources : Jewish Itineraries (de Silvio G. Cusin et Pier Cesare Ioly Zorattini)

With its Slavic name referring to the ancient fortresses of the town, Gradisca still has many buildings that bear witness to different regional and historical influences. The Jewish presence probably dates from the 16th century.

Among the famous families are the Morpurgos, who were prominent in banking but also in the interpretation of biblical texts, philology, and medicine. However, the rights granted to the Jews in the city were gradually challenged, and in 1769 they had to move to a ghetto, mainly due to jealousy from other populations.

The ghetto was located in the Giardino, near the orchard of the Seminary of Monte di Pieta. Eight houses were built there, as well as a synagogue and a silk thread factory. The synagogue was inaugurated in 1769, the year the ghetto was entered. The main street of the ghetto , Via Del Tempio Israelitico, is now called Via Petrarca. The synagogue was located at number 5 of this street. Some architectural traces remain on buildings in this street.

The segregation was ended during the reign of Joseph II and definitively abolished by the arrival of the French in 1797. The synagogue, as well as a large part of the ghetto and the walls were destroyed during the First World War. Remains of the ghetto can be seen in the Museo Documentario , which also houses old documents including maps and ketuboth.

The Jewish community had reached its peak in 1857 with 135 people. They had been able to integrate various professional activities, especially in the silk industry. Urban planning measures and the gradual change of Gradisca, which had been a cultural centre for centuries, caused many people to leave. Thus, in 1895, there were only 29 Jews left. The community became part of the larger community of Gorizia.

A Jewish cemetery is located north of the highway from Udine to Trieste. The oldest of the 78 graves dates from 1805 and the most recent from 1940.

Sources : Jewish Itineraries (de Silvio G. Cusin et Pier Cesare Ioly Zorattini)

As a border town between Italy and Austria, Cormons has been home to Jews probably since the 16th century. In 1565, the Archduke Charles of Austria granted protection to the Jews of the region.

The trades practised by the Jews diversified over time. Thus, not limited to certain financial activities, they distinguished themselves in the production of spirits and in leather. In particular, they worked with silk.

In 1764, there were 17 Jews in Cormons. The Jewish community disappeared at the end of the 19th century, mainly as a result of the rural exodus. Jewish merchants from Gorizia continued to export local fruit. The last Jew in the town was Giuseppe Pincherle, a pensioner from Trieste who settled in Cormons in the 1930s. He was deported to Birkenau during the Holocaust.

The Jewish quarter was located around the Piazzetta Patriarchi . If the area has been rebuilt, one can see what it looked like in a painting by the local painter Ermete Zardini (1868-1940). In a building on Via Patriarchi 23, plaster cornices that probably belonged to an ancient synagogue still exist.

Sources : Jewish Itineraries (de Silvio G. Cusin et Pier Cesare Ioly Zorattini)

Cividale del Friuli is a Roman town with famous walls that bear witness to its age and to the name it bears for the region. It allows you to travel back in time through its narrow streets.

The Jewish presence dates back to at least the 13th century, as documents attest. Among them, the Or Zarua of 1239 mentions the existence of a rabbinical court and a Jewish community in the town. This installation was motivated in particular by the favourable reception of the local authorities of the time, as indicated by a text of 1321 which recognises their rights.

A declaration reinforced by a contract between the town hall and the Jewish community in 1349, allowing them to live their faith and work in the city. An active life not limited to the activities forbidden to Christians by the Papacy, the Jews also integrated commerce, medicine and other trades.

There is a district still called Giudaica , but the Jewish population seemed to live in many parts of the city, especially near the Porta Brossana. The situation of the Jews of Cividale declined from the 15th century onwards. In 1572, their expulsion was decided by the Venetian authorities. There was no revival of the Jewish community afterwards.

The city’s archaeological museum displays Jewish tombstones from the 14th century from the old cemetery. The museum has many works and artefacts that trace the rich history of the region since Roman times. A Jewish tombstone with Hebrew letters is also cemented into the arch of Porta Arsenale Veneto .

Sources: Jewish Itineraries (de Silvio G. Cusin et Pier Cesare Ioly Zorattini), Encyclopaedia Judaica

Émile Zola is one of the greatest authors, presenting the many facets of France at the turn of the 20th century, from the slums of the mines of the North in Germinal to the neon lights of Parisian department stores in The Ladies Paradise.

He is also one of the most important heroic figures in French history. In particular, he defended the honour and integrity of Alfred Dreyfus.

We especially remember his famous tribune “J’accuse”. Then, their common fight for truth and justice, against anti-Semitism coming to light.

Year after year, Zola’s memory is celebrated in his summer home in Médan, while his work is still shared on the country’s school benches. His house where he wrote various novels, and not the least, from 1880 onwards. He also received his friends there. This house has recently been restored and reopened to the public.

After his death, it was donated to the Public Assistance. Its transformation into a museum provides an insight into the personal and family life of the man. The author’s taste in furniture and his passion for antiques can also be seen. We find the period decorations and elements of the stained glass windows, his stained glass window, encouraging our imagination to try to know what the author was thinking by looking at the river and the railways. All that these journeys allowed, especially in his books such as “La Bête humaine”.

It is therefore in a very harmonious and logical way that a Dreyfus Museum was built in Médan next to Émile Zola’s house. Its construction was made possible by the financial support of Pierre Bergé, at the request of President François Mitterrand. Elie Wiesel agreed to be its patron.

The Dreyfus Museum was opened on October 28, 2021 and its main mission is educational, offering teachers material that allows them to better share themes that are not always obvious today in the classroom. The aim is to share with future generations the values of these two men and their courage in the face of adversity, by showing xenophobic speeches and anti-Semitic caricatures.

But also texts and images of support, including many Armenian authors. A dialectic leading to an even higher honour for France. By explaining in detail the “Affair”, the issues at stake at the time, the struggles between and within the institutions of the Republic, as well as the role of the latter and of citizens.

At the entrance, there is the famous photo of Captain Dreyfus’ sword being broken by a warrant officer on his thigh, marking his degradation. Then, a little further on, the sentence “The truth is on the march and nothing will stop it”, which closes an article by Zola and was later found in “J’accuse”.

The Dreyfus Affair is thus largely presented through the eyes of one of its most important supporters. The museum also presents the tragic end of Zola, who was murdered, and the rehabilitation of Dreyfus.

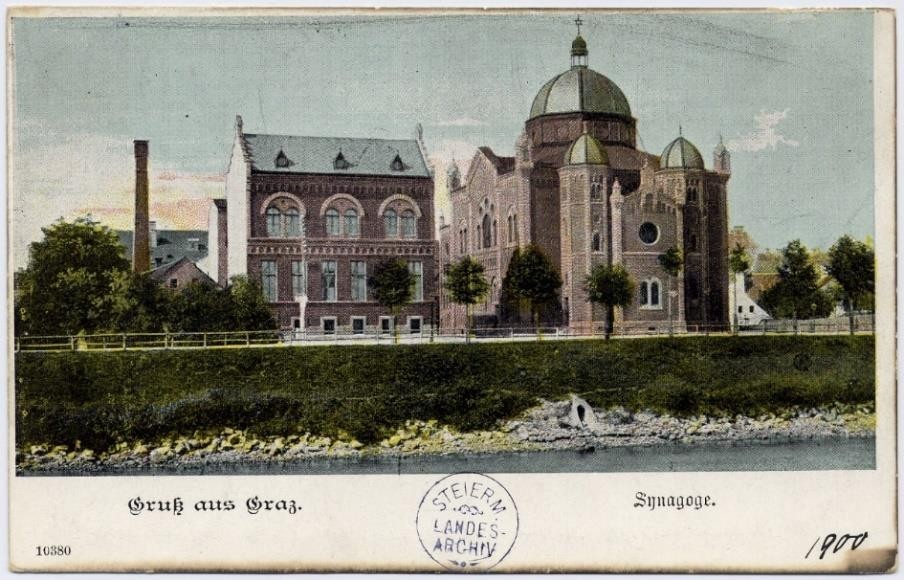

The Jewish presence in Graz seems to date back to the Middle Ages, but the only certainties point to the 12th century, but the first mention is in 1261. A Jewish community was formed at the end of the 14th century, which had a synagogue, a mikveh and a cemetery. As in most other Austrian cities, the community was very small until the end of the 18th century.

In 1783, Jews were again officially allowed to participate in trade fairs. From 1848 onward, Jewish families gradually settled in Graz. A Jewish community was again formed and developed rapidly. It consisted of 566 people in 1869 and 1720 in 1934. During this period, a synagogue was inaugurated and a Jewish cemetery opened.

Following the Anschluss of 1938, a process of aryanization of Austrian towns was set in motion by the Nazis. On Kristallnacht in November, the synagogue was destroyed and 300 Jews were arrested and deported. A quarter of Graz’s 1,600 Jews managed to flee. The Holocaust claimed many victims in the country.

In the aftermath of the war, just over 100 Jews returned to Graz to rebuild the community. A unanimous decision was taken by the Austrian parties to rebuild a synagogue in Graz, which was opened in 2000. Many of the bricks used were symbolically taken from the ruins of the old synagogue. Its construction by the architect couple Jorg and Ingrid Mayr is very original. The synagogue has a magnificent glass dome. The square on which it is located has been renamed David Herzog Platz, in honour of the last rabbi who officiated there before the Second World War. In 2020, the synagogue was the victim of an antisemitic attack.

In 2025, the community has 150 members.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, Times of Israel

The Jewish presence in Innsbruck dates back to at least the 13th century, but they settled here mainly from the beginning of the 17th century, during the reign of Duke Ferdinand II (1618-1623). In this tolerant era, they participated in civic life. However, following his death, these rights and permissions were limited, and most were expelled in the 18th century.

It was not until the constitution of 1867 that Jews settled in the city again, mainly from the liberal stream. A few hundred Jews lived in Innsbruck before the First World War. Very patriotic; a good number of them fell at the front.

Following the Anschluss and the Kristallnacht of November 1938, Jewish-owned shops and houses were confiscated and destroyed, and community leaders were murdered. More than 200 Jews from the region were victims of the Shoah.

In the aftermath of the war, about 100 survivors recreated a Jewish community. A prayer hall was opened in Zollerstrasse in 1961. In 1988, to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the pogrom, a ceremony was held in the presence of Christian and Jewish religious authorities, including Bishop Reinhold Stecher and Chief Rabbi Paul Haim Eisenberg.

As a result, it was decided to build a new synagogue on the site of the old one. The foundation stone was laid in 1991 and the inauguration took place two years later. In 1997, a menorah was placed on the Lanhausplatz to commemorate the victims of the Shoah.

There were only about 60 Jews at the turn of the 21st century. The Jewish community centre, located in the synagogue building, also has a library and a hall for events. In 2019, the community published a book about Jewish life in Innsbruck, written by Niko Hofinger, Sonja Prieth and Esther Pirchner.

The Jewish cemetery is located within the western city cemetery. They have been buried there since 1864.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, https://www.ikg-innsbruck.at/en/

The Jewish presence in Linz dates at least from the 13th century. As for the mention of a synagogue, it dates from 1335. Nevertheless, until the end of the 15th century, their situation was rather precarious, being the victims of antisemitic campaigns and leading to an expulsion in 1421 and the transformation of the synagogue into a church five years later.

Until the end of the 18th century, Jews were only allowed to participate in daytime fairs, thanks to the permission of King Maximilian in 1494. In 1783, their participation was officially accepted by the Edict of Tolerance of Joseph II. This slow development allowed them to build a synagogue in 1824. The Jewish cemetery dates from 1863. At that time, there were less than 400 Jews in Linz.

This number increased slowly over the following decades, reaching 650 in 1938. A new neo-Romanesque synagogue was built in 1877 and opened by Rabbi Adolf Kurrein, whose son, Rabbi Viktor Kurrein, wrote about the history of the Jewish community in Linz.

On Kristallnacht, 10 November 1938, the synagogue was burned down and razed to the ground, with the city’s fire brigade only allowed to protect the adjacent buildings. Jewish-owned shops were “aryanized,” and the Jews were arrested and deported, as the town was designated by the Nazis as an important place in relation to the Fuhrer’s life and therefore had to be emptied of Jews. About 300 Jews from the region were murdered during the Holocaust.

After the war, the synagogue was reconstituted with just over 200 people. A new synagogue , built on the site of the old one by the architect Fritz Goffitzer, was opened in 1968.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, https://www.ikg-linz.at/

The Jewish presence in Salzburg probably dates back to Roman times, when the city was called Luvavum. The first written record is from an earlier period, when the city was re-founded under its present name and a Jewish doctor treated Bishop Arno of Salzburg (785-871).

In the 12th century, a Judengasse, or “Jew’s alley”, was located near the cathedral. The synagogue had been located at number 15 of this alley since the 14th century. In the following century, the Jews were attacked and expelled from the city.

It was not until the end of the 19th century that the Jewish community was able to re-establish itself. In 1893 a synagogue was built at 8 Lasserstrasse and a year later a Jewish cemetery was built. Theodore Herzl, who stayed in Salzburg as a lawyer, described the climate of the time as being between a certain softness of life and a clear presence of anti-Semitism. This vision, which oscillated between enthusiasm and fear, was included on a memorial plaque in Salzburg a hundred years later.

However, despite certain fears, Jews were able to contribute to the cultural and artistic influence of the city. Max Reinhardt and Hugo von Hoffmannsthal, for example, were very active in the creation of the Salzburg Festival. In the 1930s, the author Stefan Zweig welcomed the European intelligentsia.

Following the Anschluss of 1938 by Nazi Germany, the synagogue was destroyed, and the Jewish population was the victim of much violence. 70,000 Austrian Jews were murdered during the Holocaust, mainly in Vienna, which was the main community. About 400 stolpersteine, or memorial stones, have been placed in Salzburg in memory of the Jewish and non-Jewish victims of the Shoah.

Today, about 100 Jews live in Salzburg. The synagogue has been rebuilt and is used by worshippers mainly on Shabbat and on major holidays.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, Times of Israel

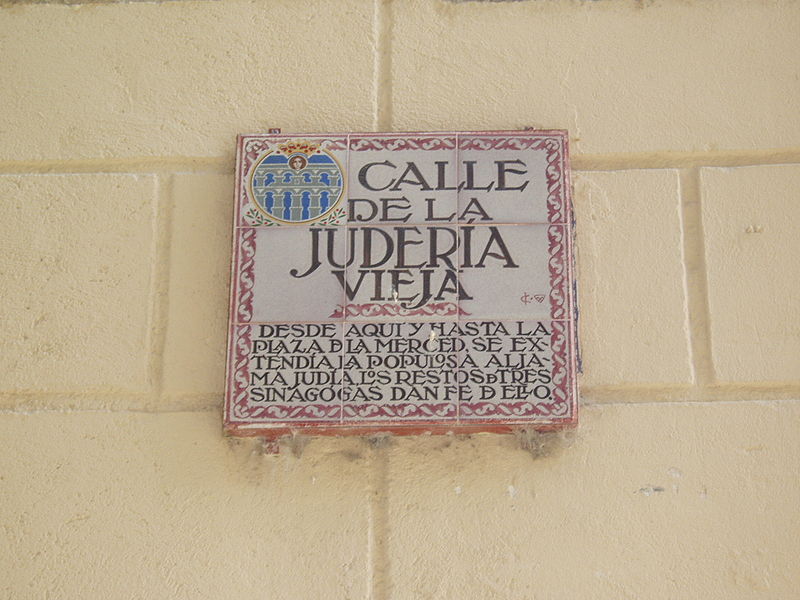

The Jewish presence in Zaragoza probably dates back to Roman times. The Jewish quarter was mainly located within the walls built at that time, in the south-eastern part. This was the case until the Inquisition.

Six gates led to it. No longer existing, it was located between the Seminary of San Carlos and the Magdalena Square, with its centre on Santo Dominguito Street. The neighbourhood housed a synagogue, a butcher’s shop and a hospital.

Following the development of the Jewish community in the 13th century, another Juderia was built to the south of the old one, between Coso and San Miguel streets. This area is now called Barrio Nuevo. Many synagogues were built here.

The Jews worked mainly in the textile industry. With the famous draperos, displayed in shops inside and outside the Juderia. A flourishing economy, but one that was accompanied by severe differences in the standard of living among the Jews of Zaragoza, prompting the creation of numerous educational, social, and medical institutions to help the Jewish workers.

Nevertheless, during the first half of the 14th century, the situation deteriorated for the Jewish community as a whole, mainly due to the very high taxes and, above all, to the Black Death, which decimated the majority of its followers. The rebirth of the community in the second part of the century was notably the work of the Cavalleria family. First of all, Don Vidal de la Cavalleria was a prosperous businessman close to the kingdom and a great scholar. Then, Judah Benveniste de la Cavalleria, who developed the family business and whose house served as a centre of learning in the 1370s.

Then it was Hasdai Crescas (1340-1410) who took over the leadership of the community. A successful businessman, he was best known in Zaragoza for his great talmudic and philosophical knowledge. And much more, since after the persecutions of 1391, which had little effect on Zaragoza, where the king maintained a residence and ensured the protection of the Jews, Crescas, who lost his son during these persecutions, organised aid from Zaragoza to the Jewish communities of Navarre affected by the riots. A street in Jerusalem was named in 2011 in honour of Hesdai Crescas.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

The Jewish presence on the two small islands of the Balearic Islands seems to date back to Roman times. The Jewish population increased, especially in the 13th century, as the islands were a haven during the difficult times of the 14th and 15th centuries. Often serving as a point of departure to Italy or other places.

There was a juderia in Ibiza until the 19th century. Part of the Convent of San Cristobal was used as a synagogue. The island of Formentera also had a synagogue until 1936. In 2017, there were still about 60 Jewish homes on Ibiza.

Very touristy and festive places today, the islands host a delegation of the Chabad movement, which animates holiday receptions and distribution of kosher meat.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, Times of Israel

The Jewish presence in Avila dates back to at least the 4th century. A mention has been found at that time. The community gradually became one of the largest in Castile.

At the end of the 11th century, a repopulation of the region took place by order of King Alfonso VI, including Sephardic families. About fifty Jewish families lived in Avila in the 13th century, most of them practicing trades related to crafts and commerce. A Talmudic school was established, which was attended by Moses de Leon and Yossef de Avila, author of the Zohar.

Nevertheless, in 1366, they were attacked by rioters. Subjected to violence and heavy taxation, some of which is documented as early as 1144, the Jewish community remained very present in Avila, gathering about a hundred families in the 15th century. They were also forced to gather in a particular area of the city, near the Malaventura Gate. A garden there now commemorates Moses de Leon.

The Jews lived in different parts of the city, but most lived between the present Reves Catolicos and Vallespin. Avila had several synagogues located on Calle Reves Catolicos (where the chapel of Nuestra Senora de las Nieves is today), in Calle del Pocillo and another in Calle de Esteban Domingo . The city has invested in the enhancement of Jewish cultural heritage, building the Jardin de Sefarad , a memorial garden in a former cemetery in 2013.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Juidaica, redjuderias.org, Times of Israel

The Jewish presence in the city of Béjar seems to date back to at least the 12th century. A time when the community was of particular importance, with Jews at one time representing almost 20% of the total population.

This development continued after the violence of 1391 and the consequent arrival of Jews in the region. With its aljamas, a large Jewish quarter where there is a synagogue, a yeshiva, a mikveh and other institutions.

Following the Inquisition of 1492, many Jews had to flee Béjar, often taking with them the memory of the town by changing their family name to Behar, Bejar or Berajano…

The David Melul Jewish Museum , named after one of its great contributors, is located in a 15th century building next to the Church of St. Mary. Among the objects presented in the museum, one can find the Béjar Charter, which organised the cohabitation between the different cultures. But also a tombstone from the Middle Ages and ritual objects. The history of the Jews of Béjar and of the Marranos who remained in the town is also presented.

Sources : Redjuderias.org, Museojudiobejar.com

The regional Jewish presence probably dates from the 4th century. The town of Monforte de Lemos, with its medieval charm still very present, was founded at the beginning of the 12th century and the Jewish population participated in its active life relatively early.

The Jewish population grew as a result of exiles from other Iberian cities that were badly affected by the wars of religious conquest and persecution in the country. The Jewish community seemed to have a synagogue and a mikveh, while living in mixed neighbourhoods.

The oldest place where they lived seems to be A Calesa, a street now called Rua Abelardo Baanante , about 100 metres from the town’s tourist office. Then go past the Monforte Castle to Rua Falagueira , opposite the old town hall. Here you will find a house that probably housed the synagogue. In the same street was located the house of the Gaibor family, famous at the time. You can walk through this charming town, which has many traces of the Middle Ages in its houses and stories handed down from generation to generation. The streets named above, as well as the Rua Pescaderias and the Rua Puerta Nova , in these paths that are more circular than straight and whose detours are rewarded with the tutelage of history.

Sources : Redjuderias.org, London Traveler

The Jewish presence in Lorca probably dates back to the 13th century. At that time, they were part of the active life of the city, participating in its economic and political evolution, and living for a large part of them in the surroundings of Lorca Castle.

Among them was José Rufo, who in the 15th century was in charge of the maintenance and defence of the castle. During this period of relative prosperity, they practised different trades: cattle breeders, grain farmers, tax collectors. Less than 200 Jews lived in Lorca at that time.

During archaeological excavations in the area of the castle in 2002, undertaken to develop it into a Parador de Turismo, many traces of the old Jewish quarter were found. In particular, the synagogue , one of the only ones not to have been transformed into a church following the Inquisition, still has an intact bimah.

A reconstruction of elements that belonged to the synagogue is on display, including 27 lamps reconstructed from 2600 glass fragments found during the excavations. Dwellings from the old Jewish quarter have also been found and can be visited today. The Municipal Archaeological Museum also has many of the objects found, which are accessible: menoroth, lamps, ceramics, etc.

Sources : Redjuderias.org, Jta.org, Times of Israel

The Jewish presence in Estella dates back to the 11th century, in what was once one of the main communities in Navarre. The town was founded to protect the route to Santiago de Compostela.

Benefiting from privileges compared to many other Spanish towns, the Jews settled in the town in large numbers from the 12th century onwards, living in the citadel of Estella and in the surrounding area, such as the Elgacena district . They represented 150 citizens, participating in the social and institutional life of the city.

Their situation deteriorated at the end of the 13th century and especially at the beginning of the 14th century, following the death of the king in 1328. Many Jews were murdered in riots and their houses sacked. Queen Juana II took sanctions against those responsible for the riots.

The community was rebuilt in the second half of the century, with 85 Jewish families present in Estella in 1366, mainly from France and England. Charles II even appointed Judah ben Samuel Halevi as High Commissioner to the Crown. Leon Horabuena, the chief rabbi of Estella, served as physician to King Charles III. The kingdom welcomed other Jewish refugees from the surrounding persecutions. However, following the Inquisition of 1492, they were no longer spared.

The Jewish quarter, located today in the oldest part of the city, can still be seen in the remains, such as the protective walls of the quarter. The church of Santa Maria Jus del Castillo was built on the site of the old synagogue. Archaeological excavations were undertaken in Estella at the beginning of the 21st century, particularly with the aim of (re)discovering its Jewish cultural heritage. In 2015, the town celebrated Hanukkah for the first time, in a sign of reconnection with this past, although few Jews live there today.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, Redjuderias.org, Times of Israel

The Jewish presence in Calahorra dates from at least the 12th century, making it one of the oldest in Castile. They were involved in many economic activities, including real estate, trade and wine growing. Documents, some in Hebrew, attest to this.

About 50 families lived in Calahorra at the beginning of the 13th century. By the end of that century, they numbered almost 500, representing about 15% of the total population. Although they were socially integrated and participated in many constructions for the benefit of the city, such as the mills, they were subjected to heavy taxation because of their religious affiliation.

In 1370, a large number of Jews left the difficult conditions of local life, especially because of regional conflicts, their neighbourhoods being plundered, to find refuge in Navarre, welcomed more favourably by Queen Juana. They later settled there again, when the drastic measures against them were eased, but not for long. In 1491 the Jews were forced to wear distinctive signs. After the Inquisition in 1492, the synagogue was transformed into a church and later into the monastery of San Sebastian.

The Jewish quarter was located near the castle of Calahorra and the present-day church of San Francisco. It was surrounded by a wall and several enclosures, including the Puerta de la Juderia , located at the current junction of Cabezo, de los Sastres and Dean Palacios streets. The ancient synagogue was located on the site of the present-day Aurelio Prudencio School.

Although few remains of Calahorra’s Jewish past remain, the Cathedral Museum preserves Torah scrolls, as well as administrative documents of real estate contracts, among which six written in Hebrew and dating from the 13th and 14th centuries.

Sources : Redjuderias.org, Encyclopaedia Judaica

Built on the ruins of the Roman city of Saguntum and also called Murviedro, Sagunto probably bears witness to one of the oldest traces of Jewish presence in Spain, dating from the 2nd century. Lead plaques with Hebrew inscriptions have been found on the city’s castle.

When the city was conquered by the King of Aragon, the Vives family was given a bakery as a thank you for their efforts during the siege. Many other personalities, such as Salomon de la Cavalleria and Joseph ibn Saprut also served the monarchy. The medieval Jewish quarter was located between the streets Segovia and Ramos. In 1321, the Jews were allowed to fortify their quarter to protect themselves from attacks.

Taking refuge in the fortress during the persecutions of 1391, the Jews of Sagunto remained one of the only communities in the area following the persecutions. At the turn of the century, the Jewish population, estimated at 600, enjoyed relative freedom and royal protection, becoming one of the largest in the Kingdom of Valencia. The development was such that at one point the Jews represented almost a third of the population of Sagunto.

However, following the Inquisition of 1492 and the massive conversions, most of the Jews left the city, mainly to take refuge in Oran and Naples. The synagogue was probably located at the corner of Sang Vella and Segovia streets. A wall has been preserved.

However, the old Jewish quarter is one of the best preserved in Spain thanks to the protection given during the persecutions of 1391. Its entrance is located at the Portalet de la Juderia , near the Roman Theatre. This gate, built during the fortifications of the neighbourhood, is one of the only remains of Jewish life at that time.

A mikveh has also been found in the neighbourhood, which can be accessed by descending some steps. On a hill near the castle there is an important Jewish necropolis , some of whose artefacts are on display in the castle. The lead plaques mentioned at the beginning of this article are currently on display in the city’s Historical Museum .

Sources : Redjuderias.org, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Wikipedia

The Jewish presence in the ancient city of Tarazona dates back to at least the 12th century. So old, that it may even have been present in Roman times. This presence developed, especially in the following century. The town’s location, next to Navarre and Castile, contributed to its commercial and strategic development.

The Jewish community of Tarazona was one of the most important in the kingdom of Aragon, enjoying long periods of prosperity, with some great families such as the Portellas. The central figure was Moshe de Portella, a financier to the King of Aragon, whose name is now borne by an association that researches the city’s Jewish cultural heritage.

This development materialised to such an extent that there were two Jewish quarters, one preceding the other in time. Each had a synagogue. The old quarter was located between the streets Rua Alta and Conde. A street in the district is still called “Street of the Jews”. The remaining façade of the synagogue can also be found here. The more recent neighbourhood was located near Rua Aires . A Jewish cemetery was located near these areas.

The situation of the Jews of Tarazona developed somewhat differently in the late 14th and early 15th centuries compared to other Spanish cities. They even enjoyed official protection by the municipal authorities and a period of prosperity under Alfonso V and Juan II in the 1430s and 1440s, before the inevitable Inquisition decreed by the central power in 1492.

Some sixty medieval documents in Hebrew were found in Tarazona at the turn of the 21st century, and this has led to further local research. A festival on the return of the Sephardim to Tarazona was subsequently organised.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, Redjuderias.org, Jta.org

The Jewish presence in Tui probably dates from the early Middle Ages. However, as municipal archives have been lost, the first written traces referring to this presence date from the 15th century. Some of them refer to orders made by a cathedral to Jewish goldsmiths, Abraan and Jago. The Jews practised a variety of activities, including medicine and trade.

Regional conflicts and the growing climate of intolerance in the 14th and 15th centuries made this life very difficult. The synagogue was converted into a stable.

Documents also refer to a probable mikveh and a kosher butcher shop, which have also disappeared. According to research, the ancient synagogue was located in the Juderia near the streets of Las Monjas and Bispo Castanon, which still have many houses reminiscent of the medieval past. In the latter is the former house of the merchant Salomon Caadia. The Sarmiento-Celeva manor house was built on the site of the synagogue. Tyde Street was home to a significant number of Jews at that time.

On the cathedral of Tui, there is an amazing engraving of a menorah. In the Diocesan Museum there are exhibits related to this past. Among them are five paintings evoking the Inquisition and its crimes.

Sources : Redjuderias.org

The Jewish presence in Plasencia probably dates back to a few years after the foundation of the city in 1186 by Alfonso VIII. They lived mainly in the Mota neighbourhood, around the synagogue. Nevertheless, some families settled in other parts of Plasencia.

The 13th century witnessed different degrees of tolerance. After a few decades of allowing the development of Jewish life, rights were limited. Jewish citizens were also subjected to additional taxes, especially concerning contributions to the royal treasury. By the end of the next century, they constituted only about 50 families.

The persecutions that followed, especially those of the Inquisition in 1492, encouraged their departure.

There were several synagogues in Plasencia. One of them was transformed into a church, named Santa Isabel, after the queen. Another suffered the same fate, becoming the church of San Vicente. The Jewish cemetery was also confiscated.

Traces of this Jewish life remain in Plasencia today. Especially in the old Jewish quarter. The remains of one of the two former synagogues can be found under the Parador Nacional de Turismo . In what is called the “new Jewish quarter”, near Trujillo and Zapateria, plaques have been put up, remembering the Jewish families who lived there. The ancient Jewish cemetery can be visited, located in the area of El Berrocal. Numerous medieval documents have been found and studied by Professor Roger Louis Martinez Davila and his students as part of research leading to a publication.

Sources : Redjuderias.org, Encyclopaedia Judaica, Times of Israel