The Jewish presence in Wintzenheim seems to be very old and important, the city having been the seat of a rabbinate since 1808.

If we find traces of a synagogue in the 18th century, the one which remains today probably dates from 1750 and benefited from restoration works in 1828 and 1870.

The synagogue was classified as a historical monument in 1995. In 2000, on the occasion of the 250th anniversary of the synagogue, a great ceremony was organized. In the presence of many political and religious personalities, but also of descendants of Wintzenheim Jews.

This anniversary marked its re-inauguration, following work on the roof, the stained-glass windows and the interior of the building. Its doors are regularly opened to the public during the European Days of Jewish Culture, as was the case in 2022.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr

The Jewish presence in Westhoffen seems to be very old, as evidenced by the existence of a prayer room in the 17th century, probably dating from 1626. At that time, there were about 100 Jews in Westhoffen.

The following century, the community benefited from a synagogue, built in 1760. The synagogue, faced with the development of Jewish life, soon proved to be too small, as the town had nearly 300 Jews at the time of the French Revolution.

The decision to build a new synagogue was taken by the city council in 1860 and it was inaugurated in 1868. Nevertheless, the community diminished over time, with only 147 members at the beginning of the 20th century.

The synagogue, in the neo-oriental style, was classified as a historical monument in 1990. Among the personalities who came from this city were the Prime Minister of the Popular Front Léon Blum and the Prime Minister of General de Gaulle, Michel Debré. Michel Debré was the son of pediatrician Robert Debré, son of Rabbi Simon Debré. In 2005, Jean-Louis Debré inaugurated the Michel Debré Stadium in Westhoffen.

In 2019, the Jewish cemetery suffered a desecration of a hundred graves, adding unfortunately to a long series of such criminal events. But the magnitude of this vandalism sent shock waves through France and strengthened the national mobilization against anti-Semitism.

Filmmaker Ondine Debré, daughter of journalist François Debré and granddaughter of former Prime Minister Michel Debré, returned to her family’s hometown to make a documentary. Return to Westhoffen was broadcast in 2022 on France 3, tracing the family’s history, Jewish cultural heritage and the fight to preserve this memory and the places that embody it, also evoking the rise of anti-Semitism and the desecration of the cemetery in 2019.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr, dna.fr

The Jewish presence seems to be quite old. A synagogue welcomed the faithful in the 19th century. It was inaugurated in 1827 and restored in the 1860s. At that time, Soultz-sous-Forêts played an important role in Jewish religious institutions.

Nevertheless, it was demolished in 1897 to be replaced by a new synagogue . Destroyed during the Holocaust, the synagogue was restored after the war and reopened in 1962. But becoming too large for a diminished Jewish population, despite the arrival of Jews from North Africa, it was divided into several parts. If an oratory was maintained, a space for young people was created.

Classified as a historical monument, the synagogue was again transformed from the inside to accommodate the History Club of Northern Alsace. The synagogue is regularly open to visitors during the Heritage Days and the European Days of Jewish Culture, as was the case again in 2018.

In 2013, restoration work was carried out at the Jewish cemetery . In 2024, a commemorative plaque was unveiled near the cemetery in memory of Pierre and Clémence Gros, two young Resistance fighters from the Jewish community of Soultz-sous-Forêts. It is located on the street that bears their names.

On 7 September 2025, the synagogue in Soultz-sous-Forêts reopened its doors as part of European Days of Jewish Culture. It did the same on 14, 20 and 21 September during European Heritage Days.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr, dna.fr

The Jewish presence in Saverne seems to date from the 12th century. Nevertheless, its perpetuation dates rather from the 17th century. An oratory dating from this century would have been located in the Judenhof of the time. On the eve of the French Revolution, a synagogue was built in the same area. However, it was destroyed by fire in 1850.

In 1898 the construction of the new synagogue officially began under the direction of the architect Hannig. The synagogue was inaugurated in 1900 in a neo-Gothic and Oriental style. An adjoining building was used for school and community activities.

This same synagogue, which was inaugurated by the German authorities in 1900 when they occupied the region, was ransacked during the Holocaust forty years later. The Jews of Saverne, who numbered more than 200, were expelled and arrested, and 32 of them were murdered. On April 4, 2022, 13 Stolpersteine, or “stumbling stones” of remembrance, were laid to honor the victims of the Holocaust.

A reconstruction was undertaken after the war. The re-dedication took place on September 3, 1950. Despite the gradual decline of the community, many initiatives kept it active. In 2001, the community consisted of about 40 people. A ceremony was held in 2021, accompanied by the publication of a brochure, to celebrate the synagogue’s 120th anniversary.

On 7 September 2025, the synagogue in Saverne gave the general public the opportunity to discover Jewish liturgy during a concert organised at the venue.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr

The Jewish presence in Guebwiller dates back to at least the 13th century. About ten families lived there. This encouraged the inauguration of a synagogue at the beginning of the 14th century.

Nevertheless, following the persecutions of 1349, this community ceased to exist. As in other cities in the region in the following centuries, their presence was very limited and generally reserved for daytime trade.

Following the emancipation of the Jews of France during the Revolution, Guebwiller attracted Jewish families, which numbered 40 at that time, and then 80 families on the eve of the 1870 war.

Designed by Hartmann in a Roman-Byzantine style, a synagogue was inaugurated in 1872. Partially destroyed by the Nazis during the Holocaust, the synagogue was restored in 1957. The synagogue and the rabbi’s house in Guebwiller are protected as historic monuments since 1984. Major restoration work was carried out in March 2020, including the entire exterior, a gate and a new fence. The rectangular house is located at the back of the plot, on the east side.

The ten Stolpersteine installed in June 2023 in Guebwiller were cleaned by secondary school pupils on 29 April 2025, before new brass-covered paving stones were laid a month later. This initiative by a history teacher at the Grünewald secondary school in Guebwiller demonstrates a desire to teach history differently and strengthen the pupils’ civic and republican ties.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, judaisme.sdv.fr, leparisien.fr

The Jewish presence in Bischwiller dates back at least to the 14th century, since during the persecutions of 1349, references to those committed in the town were found. As in many other towns in the region in the following centuries, Jews were allowed to stay there during the day for certain economic activities, but not to reside there.

Thus, it was not until the consequences of the emancipation of the Jews on the national territory during the French Revolution that they settled in the city. As the industrial revolution opened up the city, Jewish families settled in the early 19th century, but their presence evolved slowly. In 1826, 17 Jews lived there. In 1851, there were less than 100 Jews, most of whom came from other towns in the region. The Jews of Bischwiller actively participated in the economic development of the town. In particular in the manufacture of sheets with Maurice Blin, known for their quality (as evidenced by the silver medal obtained at the Universal Exhibition of 1867) and whose factory provided many jobs in the region until 1976.

The demographic development accelerated in the 1850s, reaching 246 Jews in 1866. This development led to the decision in 1856 to build a synagogue. A Jewish cemetery was made available in 1857. A year later, the construction of the synagogue was undertaken at the corner of rue Leclerc and rue des Menuisiers.

Destroyed during the Holocaust, a plaque was placed in 1997 on the building where the synagogue was located. The Shoah claimed 37 victims among the Jews of Bischwiller. After the war, the community was rebuilt. A new synagogue was inaugurated in 1959. There were at the time about sixty Jews in Bischwiller, but this number decreased to a few families at the turn of the century. Bought by the town hall in 2009, the synagogue was transformed into Espace Harmonie three years later. In 2015, a commemorative plaque was placed on the building.

A concert by the choir Le Chant sacré and the ensemble Klezm’hear took place at the synagogue in Haguenau on 22 June 2025, bringing together liturgical music and klezmer folk music.

Sources: judaisme.sdv.fr, dna.fr

The Jewish presence in Mulhouse is ancient, probably dating back to at least the 13th century, but following massacres and expulsions, it did not become permanent until the end of the 18th century. There seem to have been two synagogues in the Middle Ages, but the few Jews allowed to reside there left the city in the 15th and 16th centuries.

When Mulhouse had the status of a Swiss Republic (1515-1798), Jews and Catholics were forbidden to reside there. Before the French Revolution and its consequences for the emancipation of the Jews of France and the attachment of Mulhouse, the Jews were forced to live in the surrounding villages. Mainly those of Pfastatt, Rixheim, Dornach, Zillisheim, Habsheim and Streinbrunn-le-Haut.

Gradually, therefore, professional and civic limitations were lifted, allowing a diversification of occupations and places of residence within the cities, including Mulhouse. Jews contributed greatly to the economic development of the city, especially in the weaving industry, as did Raphaël Dreyfus, the father of the famous captain. The Jewish population increased from 165 in 1808 to 2132 in 1890.

A synagogue was built from 1847 to 1849 by the architect Jean-Baptiste Schacre, in a neo-classical style.

Among the great rabbinical figures of this period was Samuel Dreyfus, the first student to graduate from the École Centrale Rabbinique de France. Under his leadership, the synagogue was built, as well as the École Israélite des Arts et Métiers and the Hôpital Israélite. Following the defeat of 1870, many Jews, like other Mulhouse residents, chose to leave the city to remain French.

Alfred Dreyfus was born in Mulhouse in 1859. The city played an important role in the Affair, as some of the major supporters and opponents were from there. The city therefore experienced great tension during the Affair. Much later, following the rehabilitation of Captain Dreyfus, the city named a street in tribute to his courage.

After the First World War, the community regained its stature. This was largely due to the two emblematic rabbis Jacob Kaplan and René Hirschler. Jacob Kaplan officiated in Mulhouse from 1921 to 1928, before becoming Chief Rabbi of France. He allowed the community to develop, particularly from the point of view of social and youth associations, with the creation of a branch of the Éclaireurs Israélites in 1928, the second after that of Paris.

He was succeeded by René Hirschler, who was barely 23 years old. He favored the development of youth movements and harmony between the different movements. He also placed great emphasis on women and the celebration of the bat mitzvah. In 1930, Rabbi Hirschler and Simone Lévy, who later became his wife, founded the Jewish thought magazine Kadimah. As early as 1933, René Hirschler actively campaigned for the reception of Jewish refugees from Germany, organizing their reception and integration. A community center opened in 1938. Very active during the Shoah to help the dispersed and hunted Jewish population, René and Simone Hirschler were captured, deported and murdered. A commemorative plaque was placed on the Mulhouse synagogue in 2016, in the presence of their descendants.

The Shoah claimed many victims in Mulhouse. The occupiers emptied the synagogue. On the occasion of its centenary, it was rebuilt under the direction of a commission appointed for this purpose and headed by Gaston Weill. A large celebration was held there in 1950, attended by Jacob Kaplan and other rabbis of the region, as well as political, religious and military representatives. The arrival of North African Jews in the 1960s gave the Mulhouse community a new lease on life.

An old Jewish cemetery was located on the site of Salvator Park. Jews were buried there from 1830 to 1890. Before that, the cemetery in Jungholtz and others in the area were used. At the end of the 19th century, the graves were moved to the new Jewish cemetery .

A remembrance ceremony was held on 29 September 2024 in Mulhouse, at the entrance to the Jewish cemetery, in front of a stele bearing the names of nearly 450 victims of the Shoah, as is the case every year, but with even greater significance given the exponential rise in anti-Semitic acts since October 2023.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr, dna.fr

The Jewish presence in Sélestat seems to date from the 14th century, marked in particular by the presence of a synagogue on rue des Clefs. Destroyed in 1470, a building was acquired by the community in rue Sainte-Barbe to establish a new synagogue.

Expelled several times from the 14th to the 17th centuries, the Jews were allowed to participate in fairs and markets during the day. The French Revolution and the emancipation of the Jews as citizens led to a settlement in the cities at a relative pace. Thus, only six Jewish families lived in Sélestat in 1814, then about twenty in 1836. In that year, a new synagogue was built in a building adjacent to the previous one.

The development of the Jewish community in the second half of the 19th century encouraged the construction of a synagogue in 1890 according to the plans of Jean-Jacques Stamm and Antoine Ringeisen. Inspired by the Romanesque exterior, its interior decoration is quite modest. It had a mikveh. During the Shoah it was desecrated by the occupiers. The synagogue was restored in the 1950s with the help of the Ministry of Reconstruction.

The Jewish cemetery of Sélestat dates from 1622 and was founded by the Jews of the city and the region. In 1948, a Memorial of the Deportation was erected there. The cemetery was classified as a historical monument in 1995. 4000 graves have been identified. Visits are organized, especially during the European Days of Jewish Culture, as was the case again in 2021.

On 2 November 2025, the choir Le Chant Sacré, from the Synagogue de la Paix in Strasbourg, gave a concert at the synagogue in Sélestat to celebrate the 65th anniversary of its restoration.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr dna.fr

In 1905, a wood merchant sold his land, on which a synagogue was built. At that time there were 36 Jews in Schirmeck, 23 in La Broque and 19 in Wisches. The synagogue allowed the Jewish inhabitants of Schirmeck and the surrounding villages to have a place of worship for a community of 79 people.

The Schirmeck cemetery was opened to the Jewish community in 1895. Previously, the Jews were buried in the cemetery of Rosenwiller. The Jewish section of the Schirmeck cemetery contains 54 graves. The last burial took place in 1979.

During the Holocaust, the synagogue was ransacked. The official reopening took place in 1946. The declining number of members led to the closure of the synagogue at the end of the 1970s, and the place was only used for summer camps. Restoration work was undertaken in 2006 on the facades and the roof. Then, having been one of the winners of the “Engaged for Heritage” prize in 2021, the restoration, already set up by a support committee, received significant support from the Heritage Foundation.

The work carried out in 2022, allowed the installation of a wooden ceiling, interior walls and an emergency exit. Jacques Ruch, president of the Association of Friends of the Schirmeck Synagogue, received a call in 2016 from a man whose grandfather had been a rabbi and liberated the town with American troops. He told him that the Torah that was in the synagogue at the time had disappeared and was currently in Israel. This Torah will find its place in the synagogue of Schirmeck during the European Days of Jewish Culture, marking also the reopening of the place.

In 2024, the foundation stone for the Wall of Names was laid. This monument, located near the Alsace-Moselle Memorial and designed by the architect Benoît Zeimett, will bring together the names of the 36,000 dead from Alsace and Moselle killed during the Second World War, who can be accessed on the memoires.grandest.fr website.

Sources : judaisme.sdv, dna.fr, france3-regions

The Jewish presence in Rosheim seems to have been quite limited in the Middle Ages, but it is attested from the beginning of the 13th century.

Expulsions, wars, and famines prevented the perpetuation of a Jewish life. But one person made history, Josel de Roheim. This lawyer and representative figure fought against anti-Semitism and for the improvement of the status of the Jews.

The perpetuation of Jewish life began at the end of the 17th century, when Rosheim had 16 Jewish families. The Jews were allowed to practice certain trades which the Christians did not want, such as the trade in old metals and clothes. Then, they practiced the trade of horses.

On the eve of the French Revolution, 53 Jewish families lived in Rosheim. At that time Lehmann Netter wrote a manuscript in which he described community life: the trades practiced by the men, the social activities of the women, the large number of rabbinical students, but also the civil information of each of these families.

Since the synagogue was destroyed by fire, the Jews of Rosheim prayed in oratories during the 18th century. A synagogue was inaugurated in 1835, then replaced by another one, in neo-roman style, in 1882.

As a sign of the improvement of the condition of the Jews in Rosheim, Aron Blum was elected mayor in 1852. The defeat of 1870 caused many Jews to leave the town, wishing to remain French. The Jewish population, which had reached its peak at that time with 310 people, gradually declined, reaching 69 people in 1936. The Shoah claimed many victims among the Jews still present.

Thus, in 1953, there were only 29 Jews left in Rosheim. The synagogue was re-inaugurated in 1959 but is no longer in use. Its facade remains intact, but the interior has been transformed into guest rooms.

Sources : judaisme.sdv.fr, dna.fr

The Jewish presence in Würzburg dates back to at least the 11th century. After the repercussions of the Crusades in the 12th century, the Jewish population increased in the following century, especially with the arrival of Jews from surrounding towns such as Augsburg, Nuremberg and Rothenburg. At that time the community had a synagogue and a school.

The development of the community at that time was accompanied by the fame of its yeshivot and the eminent rabbis who came from them. However, in 1298 it was destroyed in the Rintfleisch massacres, killing 900 Jews in the town.

In the 14th century, the Jews resettled in Würzburg, protected for a time from accusations of ritual crimes and the wrath of the mob by the bishop. But in 1349, persecution caused the death of many of them, with the survivors fleeing to other German cities.

The 15th century was more peaceful, as the community was able to re-establish itself. A synagogue was built in 1446. Persecution resumed in the following century, and it was not until the 19th century that Jewish life began to materialise again.

A synagogue was inaugurated in 1841, led by Rabbi Seligman Baer Bamberger for forty years. He was known for his yeshiva, but also for his teacher training school, which trained hundreds of teachers of Jewish studies. The development of the community at that time allowed the number of Jewish people to reach 2600 in 1925.

With the rise of Nazism, many Jews fled, and the synagogue was destroyed during the Crystal Night. The majority of Jews who remained were murdered during the Holocaust. Very few Jews returned afterwards. Another one was inaugurated in 1970. During building work in the mid-1980s, 1508 Jewish headstones and graves were discovered, dating from the Middle Ages.

The community was strengthened by the arrival of Jews from Russia. In 2006, the Shalom Europa community centre was opened. It exhibits some of the medieval Jewish tombs found in the 1980s. It also presents the history of Jewish life in Würzburg over the past 900 years and its diversity.

An ancient Jewish cemetery can also be visited. In 2020, a Holocaust memorial was installed at the main railway station from where the Jews were deported. It was created by the artist Matthias Braun. It shows many suitcases, symbolising the departures.

On 5 June 2025, Torah mapoth, intended to protect the parchment, donated to the synagogues of Würzburg and Kitzingen in the 1920s and probably scattered after the pogroms of 9 and 10 November 1938, were returned thanks to the Museum of Jewish Art and History, which had safeguarded them for many years.

The Jewish presence in Rothenburg dates back to at least the 12th century. The first mention of this presence dates from 1180. The establishment of a community in the following century, around 1241, when it was asked to pay a special tax.

At that time, Rabbi Meïr settled in the town, followed by many pupils. Known as the Maharam, he was considered one of the greatest Talmudists of his time. His success enabled his yeshiva , located on Kapellenplatz, and the town of Rothenburg to become an important place for religious studies.

A plaque commemorates the site of the former yeshiva. This area was home to most of the city’s Jews at the time. An ancient Jewish cemetery was located nearby.

In 1298, during the Rintfleisch persecution, the majority of the Jews were murdered. A timid return of the Jews took place in the 14th century, as shown by the presence of a Judengasse from 1371, where Jews and Christians lived peacefully together. It is one of the oldest streets of its kind in Europe. But they were again victims of terrible persecution in 1349.

In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Jews were alternately protected and persecuted, depending on the will of the political and religious authorities.

It was not until the end of the 19th century that a Jewish community was able to establish itself permanently, but it did not exceed 100 members from that time until 1933. After the Nazi takeover, there was an absence of Jewish life in the town.

The town’s Museum exhibits ritual objects and Jewish graves from the Middle Ages. On display are Hebrew inscriptions on stone relating to the pogrom of 1298 and a menorah. A medieval mikveh is located at 10 Judengasse, but is not open to the public.

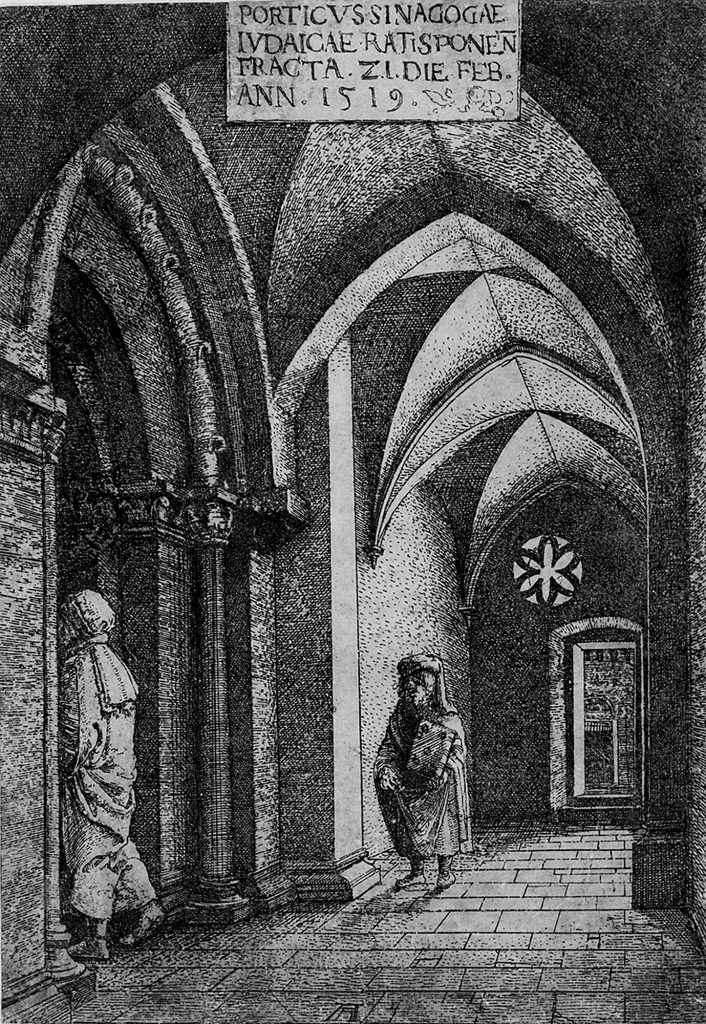

The Jewish presence in Regensburg is very old, dating from the Middle Ages, probably around 981. A Jewish quarter existed there since the 11th century. In the 12th century they gained more freedom, especially in working life. In 1210, the construction of a synagogue was started and land for a Jewish cemetery was purchased. The synagogue was inaugurated a few years later and could accommodate about 300 worshippers. The town soon became an important centre of Jewish life, with its yeshivot. There was also a mikveh.

This development and the freedom that accompanied and motivated it, declined from the 14th century onwards. This development and the freedom that accompanied and motivated it declined from the 14th century onwards. The Jews were subjected to particularly heavy taxes, and their field of activity was limited. Due to financial and religious pressure, the 600 or so Jews were finally expelled in 1519. The synagogue was razed to the ground, and the gravestones of the Jewish cemetery were used for building works.

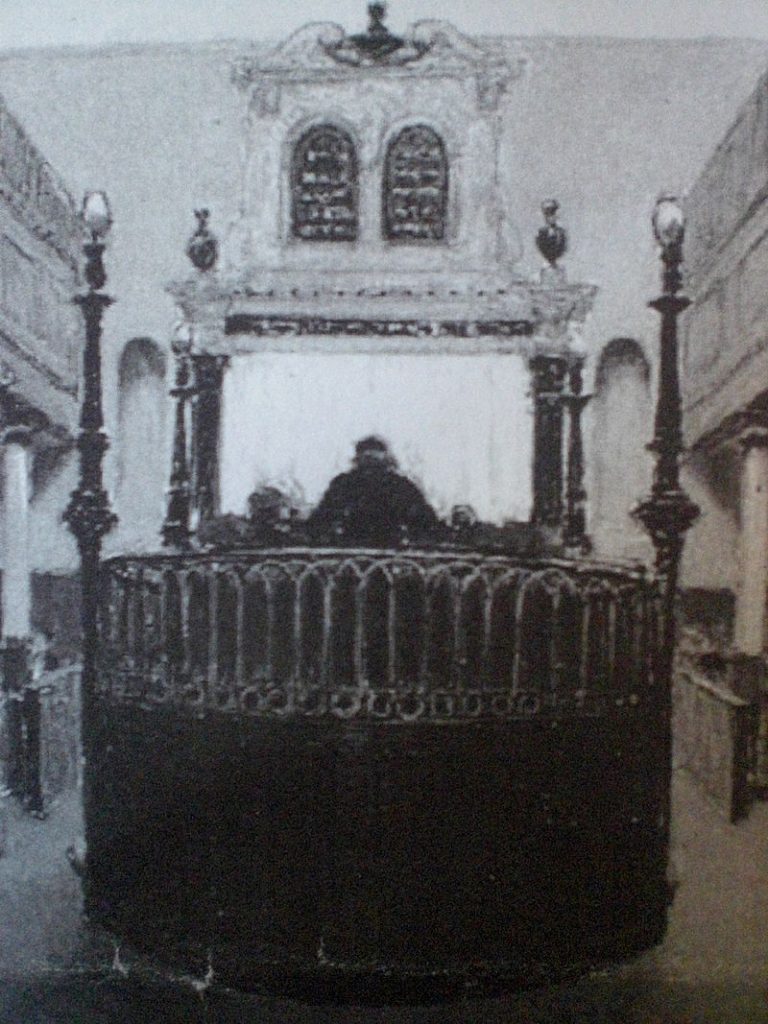

In the 17th century, Jews began to return to the city in small numbers. Jewish personalities participated in the intellectual and economic development of the region. In 1753, Isaac Alexander was the first officially appointed rabbi, officiating in a baroque building used as a synagogue . A new Jewish cemetery was purchased in 1822 and a synagogue built twenty years later, with a downstairs room for men and a balcony for women.

At its peak, the Jewish community consisted of 635 people in 1880. However, the poor condition of the walls forced the end of the use of this synagogue at the turn of the century. A 19th century mikveh was found as a result of archaeological excavations and is now located in a private residence.

At the beginning of the 20th century, the Jewish population declined, which of course continued when the Nazis took over in 1933. Thus, of the 81106 inhabitants of the city, only 427 are Jewish. Nevertheless, the cultural and religious city continued. The Judischer Kulturbund had 200 members and organised many events in the city.

Until 1937, the community functioned with a synagogue, a school, social and cultural associations, and a library, fighting in parallel against the anti-Jewish measures that accumulated over time.

The synagogue, a modern structure accommodating 500 worshippers and inaugurated in 1912, was burned down in 1938, a year that saw the flight of 268 Jews. The Crystal Night claimed many Jewish victims, as did the deportations that followed, notably the one in 1942 when 106 Jews were sent to extermination camps.

The community experienced a tentative post-war revival with the construction of a cultural centre in 1969, its population reaching 140 in a census a year later. This figure rose sharply to 1000 at the turn of the 21st century, largely due to the arrival of Jews from the former USSR.

Archaeological excavations in the 1990s near Neupfarrplatz, where the old Jewish quarter was located, uncovered numerous ruins of medieval buildings, some of which are linked to the Jewish history of the quarter.

In 2013, citizens, mostly non-Jewish, mobilised to rebuild the synagogue on the site of the old one. After many efforts by the local and regional authorities and private contributions, this project came to fruition in 2019, replacing the few small places that were in use.

Marranos fleeing the Inquisition settled in Hamburg at the end of the 16th century. They quickly became active in the city’s life, making their mark in many professions related to the city’s economy: port construction, banking, weaving, sugar and tobacco imports… But also, the printing of books in Hebrew. The Sephardic community had three synagogues in the 17th century.

Shortly after the establishment of Sephardic Judaism in Hamburg, an Ashkenazi community was established in the early 17th century. This community was strengthened by the arrival of Jews from the East, fleeing persecution. In 1671, the three congregations of Hamburg, Altona and Wandsbek united.

At the beginning of the 19th century, about 6,500 Jews lived in Hamburg. The political activity of Gabriel Riesser enabled the Jews to obtain citizenship in 1850. A great deal of cultural activity took place, including the art historian Aby Warburg and the philosopher Ernst Cassirer. Hundreds of books in Hebrew were published between the 17th and 19th centuries. One of the first liberal synagogues was built in Hamburg in 1844, mixing Gothic and Moorish styles. The ruins of this synagogue can be seen today.

Hamburg possesses ancient Jewish cemeteries, among them the Altona cemetery with Sephardic and Ashkenazi graves and the Ohlsdorf cemetery where many soldiers are buried.

At the turn of the 20th century, the Jewish community became one of the largest in Germany, with nearly 20,000 Jews. After the Nazi regime took over, thousands of Jews fled. About 9,000 Hamburg Jews were murdered during the Holocaust.

In the aftermath of the war, a small community of hundreds of surviving Jews was established. Until the end of the 1980s, the number of Hamburg Jews fluctuated between 1,000 and 2,000. The arrival of Jews from Iran and the former USSR strengthened the community. In 2020, the decision was made to rebuild the Bornplatz synagogue . In 2025, there are about 2,500 Hamburg Jews.

In 2025, more than 5,000 Jews in Hamburg are proof of the development of Jewish cultural life in this port city. A project is underway to rebuild the large synagogue on Bornplatz, a testament to this revival. This is despite the rise in anti-Semitic acts and the desire of extremists of all stripes to make the Jewish presence and memory invisible in most European cities, including Hamburg, since the pogrom of 7 October. The city of Hamburg, along with other local and national authorities in Germany, is actively fighting against this staggering rise in anti-Semitic acts.

The Jewish presence in the city seems to date from the 13th century. Following the expulsion, they only resettled there in a stable manner at the end of the 16th century, even if their numbers were very small. This did not prevent a synagogue from being built there in 1683.

The Jewish population only increased in the 19th century, from 19 in 1805 to 750 in 1869 and nearly 5,000 in 1930. Many Jews were deported and murdered during the Holocaust. About 100 survivors returned after the war.

An imposing Byzantine-style synagogue , built in 1913 by the architect Edmund Korner at the instigation of Rabbi Salomon Samuel, is one of the last vestiges of Jewish life before the war. It is one of the largest in Germany, measuring 70 meters long and 37 meters high.

Severely damaged during Kristallnacht, it was restored several times after the war, including in the 1980s to its original appearance. Today it is used as the House of Jewish Culture, presenting exhibitions and hosting events.

A synagogue was built in 1959. The small Jewish community was strengthened by the arrival of Jews from the former USSR.

In 2022, the Essen rabbi was shot at by a gunman in his home near the synagogue, but thankfully escaped.

The Jewish presence in Bayreuth probably dates from the 13th century. This can be traced in the writings of Rabbi Meir of Rothenburg. Until the end of the 17th century, they were alternately expelled and readmitted to the city, depending on the good or bad will of the Margraves.

The intervention of Samson of Baiersdorf enabled them to settle in Bayreuth on a more permanent basis. The Jewish population increased from 135 families in 1709 to 346 in 1771. However, the number declined in the following centuries. The Shoah decimated the small Jewish community that lived there at that time.

After the war, a new community developed, which was strengthened by the arrival of Jews from the former USSR.

The city has a beautiful baroque synagogue that was built in 1759. Inside is a mikveh, probably the oldest still functioning in the country. The synagogue has been restored several times, including in 1965 and 2012. A Jewish cemetery can also be visited

Excavations undertaken in the city since 2006 to explore an archaeological site led to the discovery in 2019 of the ruins of a synagogue probably dating from the 13th century.

This is one of the oldest traces of Jewish presence in the country, after the 3rd century synagogue in Plovdiv. One of the elements reinforcing the possibility that it was indeed a synagogue is the presence of an engraved Star of David.

An important city in the past, it was also historic for its ability to bring together different populations.

A beautiful synagogue was built in Vidin in 1894 by the architect Friedrich Grunanger. A two-storey building with impressive stained-glass windows. Grunanger was inspired by the Great Synagogue in Vienna. At the time, the Jewish community numbered around 1,500 people.

At that time, about 1500 Jews lived in Vidin. This number increased on the eve of the Second World War.

It was damaged by bombing raids during the war. Although a large part of the compound remains, the roof is no longer present. Only a dozen Jews still live in Vidin in 2025.

In 2022, the transformation of the synagogue into a cultural centre was undertaken. The municipality of Vidin has been working for two decades to enhance the Jewish cultural heritage of the city.

The Jewish community in Canterbury appears to be very old. But the earliest administrative record dates back only to 1760, with the purchase of land for a burial.

A synagogue was built at that time in St Dunstan’s. Following the expansion of the railroads in the mid-19th century, the land was requisitioned. A new synagogue was inaugurated in 1848, thanks in part to the financial support of Moses Montefiore.

The architecture of the synagogue is very original with its Egyptian-style columns, but also because of the materials used in its construction, such as the cement chosen. It also had a mikveh in the same Egyptian style. The building was later sold as a result of the decline in the Jewish population. Nevertheless, it still remains in its current state, attracting many visitors. The building is attached to the King’s School, which lends the site to local Jews for the celebration of major holidays.

At the turn of the 21st century, the Jewish population was 210. A Jewish cemetery dating from 1760 is located north of Whitstable Road and contains 150 graves.

Few Jews lived in Mechelen before the war, but the city is infamous in Jewish history for the Kazerne Dossin. This building dates from before Belgian independence, from Austrian times. At the beginning of the 20th century, it served as a military barracks for the Belgian army. In 1942, when the Nazis were looking for a place to round up the Jews, they chose the Kazerne Dossin.

It seemed convenient because of its military configuration with a plain in the middle and walls to avoid prying eyes. In addition, there are railways right next to it. Finally, because it is located in the city of Mechelen, halfway between the two cities where the majority of Belgian Jews reside, Antwerp and Brussels.

Once the prisoners had been rounded up, they were taken by truck from Antwerp and Brussels to the Kazerne Dossin and then deported by train to Auschwitz. The first deportation took place in August 1942. When Belgium was liberated in September 1944, about 150 prisoners were found to be part of the next convoy. In all, 28 convoys left.

The German soldiers fled to Holland, which was only liberated later. They left prisoners behind, together with the administrative documents. Shortly before they fled, the soldiers had asked prisoners to burn these documents, which was not done. Therefore, a lot of documents were collected as evidence of these crimes. After the war, all these documents were transferred to the military museum. In the 1970s, there were governmental discussions about what would happen to this place. Some politicians wanted to destroy it. Then, in the 1980s, a property developer proposed to turn it into a luxury residence.

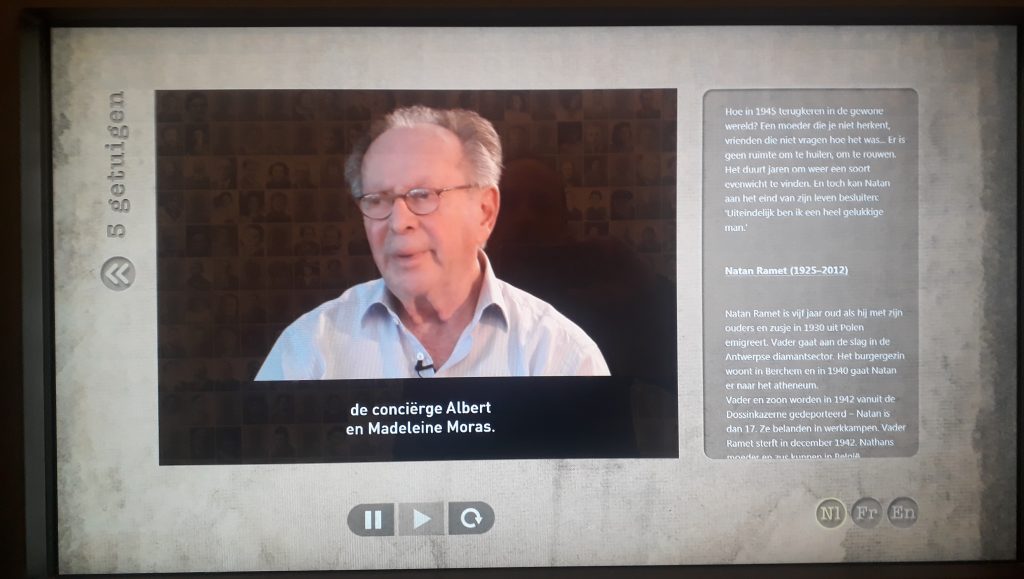

The Jewish communities of Antwerp and Brussels united behind Natan Ramet (1915-2012), a survivor of the Shoah, who did a lot of educational work with young people. Together they bought part of the building and transformed it into a memorial museum. This small museum was opened in 1996.

In the 1990s, school textbooks began to talk about the Holocaust and schools began to visit Dossin. These were very emotional moments, as the days organised by the national education system included a visit to the Breendonk camp where political opponents and resistance fighters were imprisoned and executed. As the museum is quite small, the visits became complicated with school groups of sometimes 60 pupils.

The Flemish government therefore supported the project to build a larger museum next to the Kazerne Dossin that would explain the history of the Holocaust in Belgium. It would also highlight acts of resistance and do more educational work on the issues of genocide and forced population displacement.

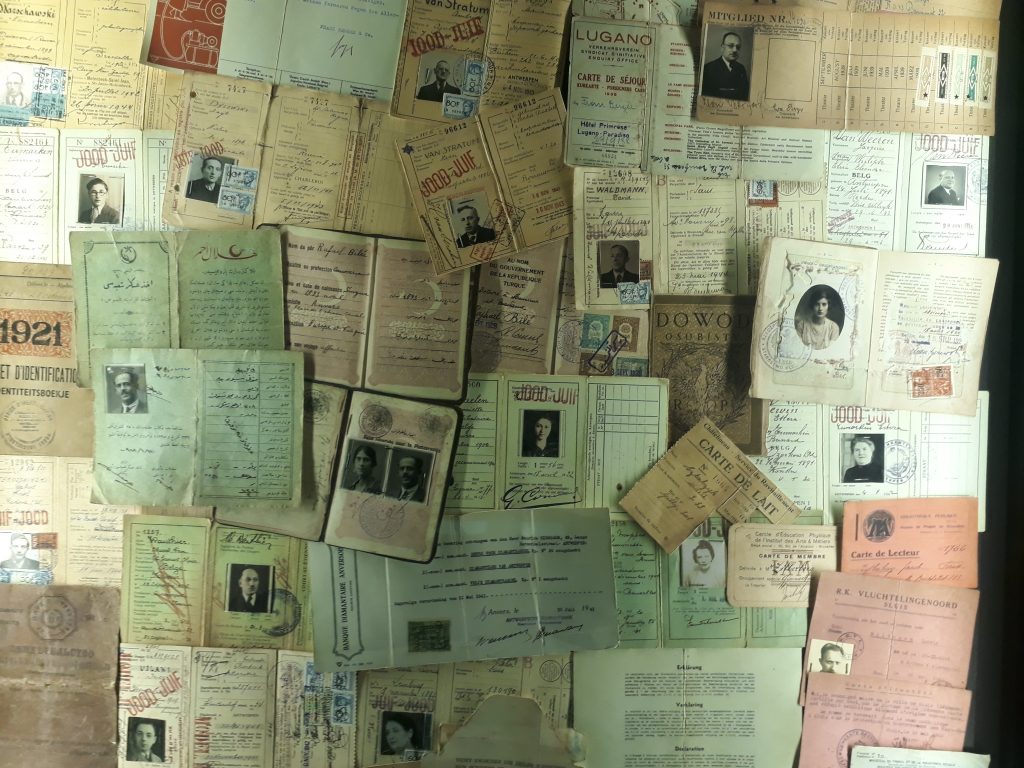

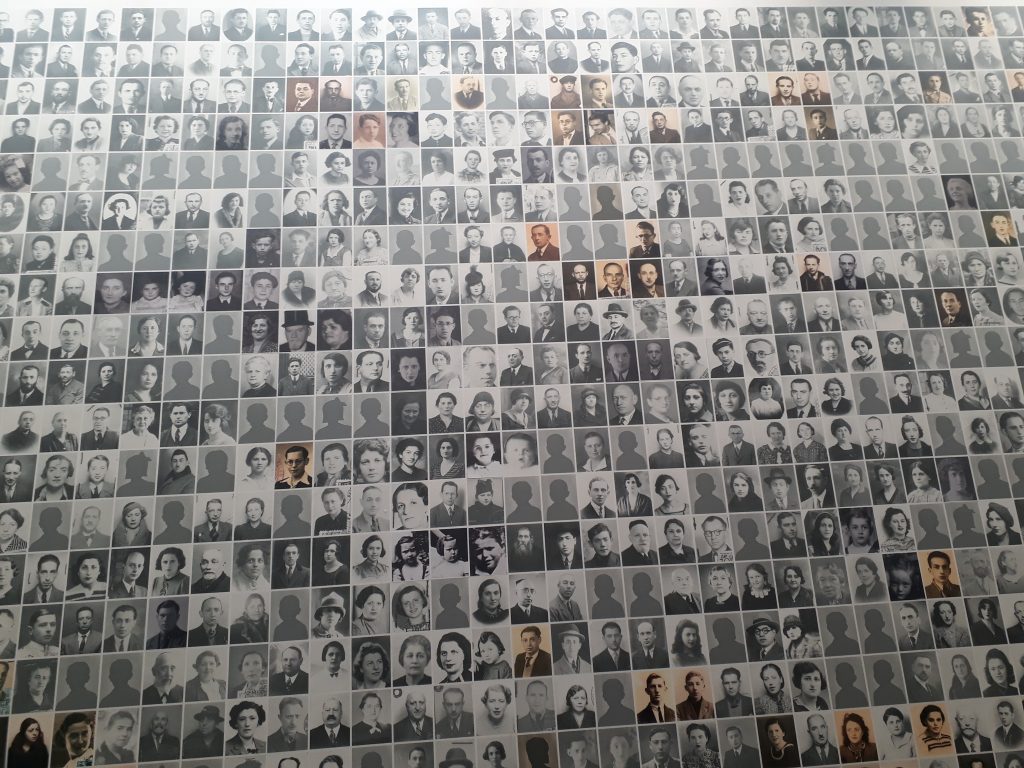

Thanks to all the documents found, Natan Ramet’s daughter, Patsi Ramet, had the idea, together with the former director of the Museum, to put a face to these names. Avoiding them to be seen as mere statistics. She spent years studying the files of the ministries on foreign Jews living in Belgium, 90% of whom were not of Belgian nationality. At that time, all migrants over 15 years of age had to add a photo ID to their file for entering Belgium. With the names on the documents left at the barracks, Patsi Ramet was able to associate many faces. She digitised all these photos, which were published in four books, including 17,000 of the 25,490 Jewish and 353 Roma deportees.

For the minors, the task was much more complicated, as there were no photos in these files. Advertisements were placed in Jewish newspapers around the world and institutions were contacted to find the missing photos.

On the inside wall of the museum are displayed the black and white photos of the more than 25,000 deportees, with boxes including just a profile of a child or adult whose photo has not yet been identified.

The photos of the 1,200 who returned from deportation are coloured in sepia. Regularly, photos are still sent in from all over the world and added during an annual ceremony.

In 1942, when the prisoners arrived, all their documents and possessions were confiscated and thrown away. When the following year the internment camp was run by another Nazi official, the documents were kept in envelopes. Of the 4,500 envelopes found, all the documents have been digitised by historians, trainees and volunteers. Each opened envelope represents a life, a passport, a ration card… and everyday documents, such as a medical prescription or the diploma of a young boy from Liege.

Today, the former Kazerne Dossin has been mostly transformed into luxury flats. The Memorial is located at the entrance to the right of the complex. Once through the front door, you enter a room with photos from which you can only see the eyes as if they were welcoming you.

In the first room, we witness how the Jewish community lived simply, assimilating into Belgian life. Photos in the street, at work, at the beach, of a banality that evokes the carefree nature of the 1930s and the way in which one could say, as the famous French phrase goes, “happy as a Jew in Belgium”.

We discover copies of documents behind glass: identity cards and other administrative papers. In the middle, a typewriter where the names of the arrivals were added by female prisoners used as secretaries.

The women sometimes managed to blur the documents by not writing down certain prisoners, in order to protect them. A projector highlights these names on pages. All these documents have been removed from the envelopes and digitised in recent years.

In the room to the right is a moving work of art by Philippe Aguirre Y Otegui, a Spanish Basque artist whose family fled during the civil war. The work is entitled ’15 August 1942′, the date of the first major round-up in Antwerp, and shows a family hiding under a table.

Then we see images of Nazis bullying Jews by shaving them and painting the swastika on them to amuse their fellow photographer. And this terrifying photo, the only one found of the interior of Dossin showing the arrival of the Jews in the camp. Nearby, drawings (notably by Irène Spicker) and paintings, in their own way, immortalised the feelings of the prisoners and preserved the testimonies, as well as a very surprising work by children.

The children’s room, in the spirit of the one at the Yad Vashem museum in Jerusalem, is a small room covered with photos of deported Jewish and Gypsy children. A little further on, a small room broadcasts on a screen the testimonies of former deportees who have been recorded, telling how the roundups were carried out.

On leaving the memorial, which was the former museum, you enter the new museum opposite the barracks. Inside, you are immediately struck by the wall of photos that extends over all the floors and by the empty boxes without any photos being found. In front of the photos is a screen that allows you to see the location of the photos according to the names.

On the first floor, the history of Germany from the end of the First World War to the rise of Nazism is presented. With anti-Semitic propaganda leaflets and a dehumanisation of the Jews representing them as insects. And also, a racist poster with a drawing of a black French soldier guarding the borders with Germany. As a welcome image on this floor, a huge contemporary photo of a crowd gathered for a festive event, contrasting with the Nazi manipulation of the masses in the stadiums, symbolising the various collective demonstrations.

Then we discover the Belgian Jewish history. How the Jews have integrated very well into Belgian life, they who originally came from Sephardic lands but the majority who arrived at the turn of the 20th century fled the pogroms of Eastern Europe.

Photos showing youth movements, students, workers and happy Saturday strollers. With stories of Jewish symbols of this beautiful integration, including a general and a great defender of the Flemish language. You can also see the paintings of Felix Nussbaum, deported in 1944, whose studio was burned down and many works destroyed. A museum is now dedicated to him in Germany.

The testimonies of five people are also broadcast: Malvine Löwenwirth, Michel Goldberg and Natan Ramet from Antwerp as well as Simon Gronowski and Marie Pinhas from Brussels. They talk about Jewish life in Belgium before the war, the deportation, the camps and their survival and return after the war, in parallel with the museum presentation.

The general life of Belgians at that time is also described. During the invasion, many Belgians feared that Belgium would definitely become a German province. The occupiers tried to calm the population by “reassuring” them. Then, in 1942, such covering up was not possible anymore when the applied increasingly brutal measures, deporting political opponents. The Walloon authorities showed more opposition and resistance to the Nazis than the Flemish authorities. For example, when Jewish lawyers were forbidden to plead, the city of Antwerp enforced this decision, unlike Brussels.

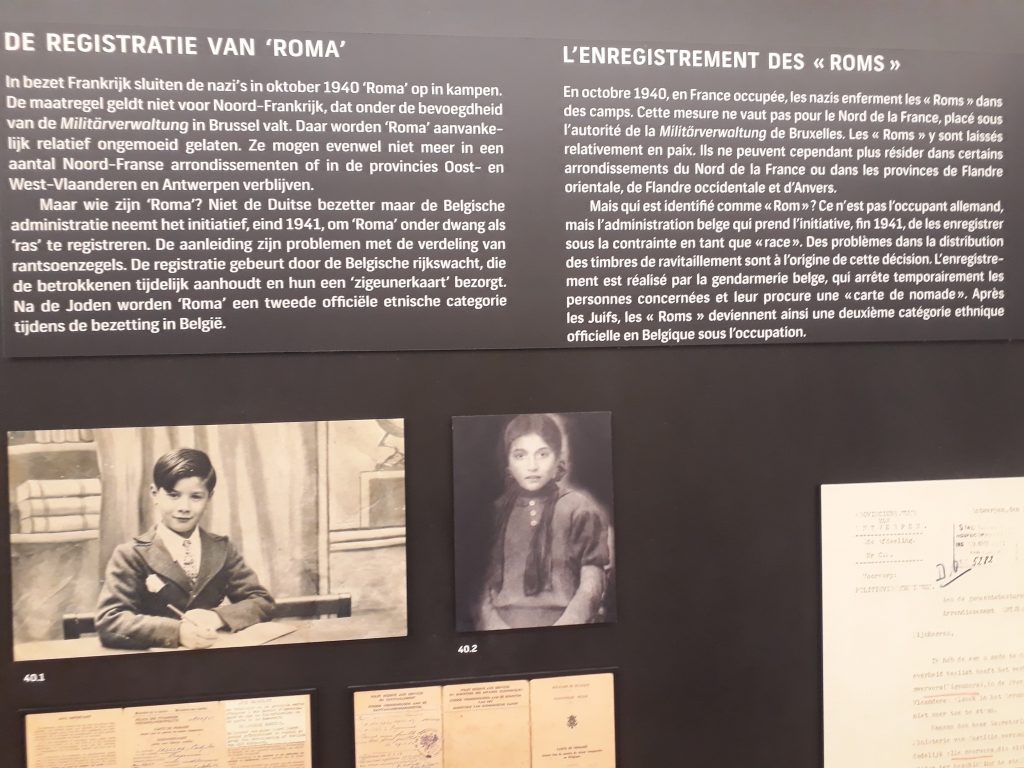

The history of the deportations of the Gypsies is presented on the walls of this floor. Among the photos we can see a family whose son is present in the room dedicated to children in the Dossin Memorial.

On the second floor, we understand how the German occupiers manoeuvred to compile the lists of Jews. In 1941, they decided that Jewish children could no longer attend public schools and had to continue their studies in Jewish schools, which also facilitated the census. How also removal companies participated in the convoys of the population.

On this floor, small stories of the daily life of the Jews who disappeared and the importance of de-socialising and dehumanising them are presented. Like this drawing in two parts, where first the Jews “monopolise” the terraces of a café while the non-Jews observe them from outside and finally, “thanks” to the Germans, the Jews are outside and the non-Jews are enjoying the good times. Also shown, a caricature of Camille Huysmans, the former mayor of Antwerp who opposed the Nazi regime.

Historical photographs show the attack on two synagogues in Antwerp on 14 April 1941 and the broken windows in the Jewish quarter, which represented a Belgian ‘Kristallnacht’. When a mob destroyed the synagogues, long before the ‘authorities’ arrived. We can see a crowd in the pictures seeming to “enjoy the spectacle” and their impassivity.

As a result of these public attacks, the dissemination of evidence of these atrocities by the Resistance, and the mere appearance of the yellow stars, many Belgians began to help Jews hide and fight the Nazi regime with greater zeal. The Nazi regime had previously tried to conceal its actions, to hide them from view, as the thick walls of the Kazerne Dossin, for example, allowed.

From 1942 onwards, acts of resistance multiplied. The Breendonck camp and the very difficult conditions of the prisoners inside are illustrated by photos. They were locked up, tortured and killed. Many pictures of Jewish resistance fighters are also presented.

Maps of Antwerp and Brussels exhibit the neighbourhoods where many Jews lived and where they were rounded up. Testimonies of police officers are displayed, some of them criticising the measures, others supporting them and one categorically opposing such measures.

On the third floor, the disturbing mob phenomena around the lynchings of blacks in the United States and the process of dehumanisation that facilitates and accelerates mass murder are also shown.

The 28 convoys of deportees are then presented, with photos and stories of the victims. Many convoys left as early as August 1942, with the first six transports taking place in three weeks. Among the deportees was a Gypsy woman who had just given birth and was transported with her 39-day-old baby.

During the first convoys, carried out in 3rd class trains, some deportees managed to escape. Tools were placed on the trains and sometimes deportees also escaped with the help of train drivers who slowed down pretending to have technical problems. Thus, 236 managed to escape, some of whom were later found and killed. Following these repeated escapes, from April 19, 1943, the 20th convoy, the Nazis transported the deportees in cattle cars. This convoy was attacked by three young resistance fighters.

The visit of the museum ends with many video testimonies and presentations things such as the uniforms of the deportees, but also a large map with all the places in Belgium where Jewish children were hidden.

The story of how these children were hidden is told by survivors and the courageous people who helped them, who explain how they had to falsify their papers and change their names, not being able to get in touch with their families. Then, disturbing photos of leisure time moments of German soldiers and their henchmen taken by them.

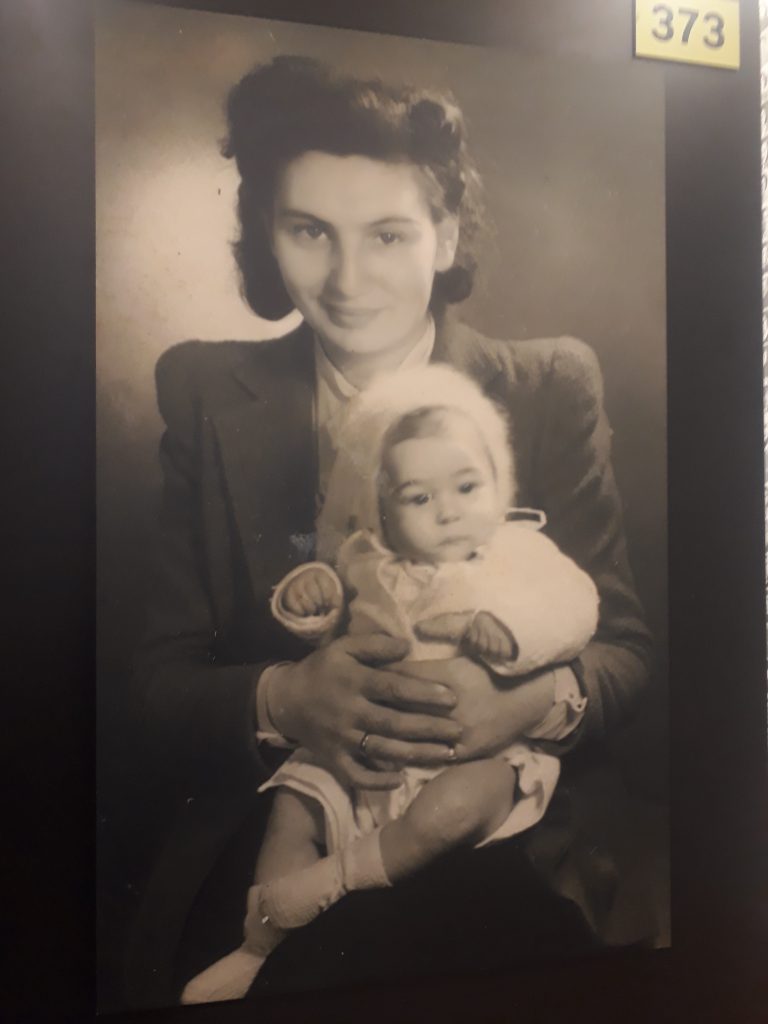

But also a note of hope, of revenge, on the death programmed by others, by the life chosen. That of the return to life of Malvine Löwenwirth, a survivor who got married in 1946 and this photo which concludes the exhibition where we see Malvine with her baby in her arms.

Mechelen is also a city known worldwide for its training in carillon music. People come from all over the world to study this in Mechelen. In Japan, the carillon is very popular. When Shinzo Abe, the Japanese Prime Minister, came to Belgium in 2018, he was accompanied by his wife Akie.

She chose what she wanted to visit: the carillon school, where a Japanese student was studying at the time, and the Kazerne Dossin, especially the part dedicated to children.

During her visit, Akie Abe asked specific questions, doing so with interest and not in a formal setting, demonstrating the importance of sharing memories and its surprising manifestations.

Article written by Steve Krief, with the precious help of Patsi Ambach, guide at the Kazerne Dossin museum

The Jewish presence in Northampton probably dates from the Middle Ages. In the 12th century it was one of the largest communities in the country. During the 13th century they were sometimes welcomed, sometimes persecuted and excluded, depending on the rulers and directives.

Jews returned to the city over the centuries. A community was formed in the 19th century with the formation of the Northampton Hebrew Congregation in 1888. Two years later it purchased a site for a synagogue on Overstone Road. It was destroyed and rebuilt on the same site in 1965.

The Jewish population was small from then until today, with a peak during the Second World War, when London Jews took refuge there. Thus, there were only 300 Jews in 1969 and 322 in 2001 and about 100 today. The Jewish community uses the Towcester Road cemetery .

A medieval synagogue was discovered in 2010 by Marcus Roberts, the director of JTrails, an organization researching English Jewish cultural heritage. It probably dates from the 13th century. It is located under a pub and a fast-food restaurant.

The Jewish presence in Newcastle probably dates from the Middle Ages. In 1234, Jews were expelled from the city. Some returned or first settled in Newcastle but it was not until the 19th century that an organized Jewish community emerged.

By the turn of 1830, about 100 Jews were living there. This was the year in which land for a Jewish cemetery was purchased. Eight years later, a synagogue was inaugurated.

Influx of Eastern European Jews

As the Jewish population grew over the century, another synagogue was built in 1868. Five years later, the two congregations joined together in a new synagogue. The influx of Eastern European Jews in the late 19th and early 20th centuries as a result of political events in the region, greatly increased the community, reaching 2,000 by 1900. The beautiful art deco synagogue was inaugurated in 1914.

Since the Newcastle community was geographically close to Gateshead, the influence of the latter’s famous Orthodox yeshiva was not negligible. In 1973, the various Orthodox streams came together to form the Newcastle United Congregation at the Jesmond location. In 1986, they met at a new site, a synagogue in Culzean Park, which also had a mikveh. The outside of the Jesmond building is still preserved with its Hebrew writings.

Decline of the Jewish population

In 1962, the descendants of German Jews who had settled in Newcastle decided to build a liberal synagogue . Prior to this, the Liberal community was assisted primarily by the Leeds community. In 1963, their synagogue was inaugurated. The synagogue had to move in the 1970s before finding a definite location in 1982.

In the second half of the 20th century, the Jewish population declined from 2500 in 1950 to 960 at the beginning of the 21st century and 600 in 2025. There are six Jewish cemeteries in Newcastle, the oldest being Thornton Street , used between 1831 and 1851. It was restored in 1981.

The Tyne & Wear Archives at Newcastle’s Discovery Museum houses an important collection of documents relating to the region’s Jewish community. Lizzy Baker, head of the archives, and Alex Boyd, coordinator of the ‘Unlocking North East Jewish Heritage’ project, are committed to raising awareness of this history and sharing it with the public in a spirit of transmission.

In 2025, the museum continues to digitise numerous documents that bear witness to the vibrant Jewish life of Newcastle’s past. This will enable us to develop this sharing and better connect the past and the present. Old documents, photos, maps of places that have disappeared…

Few Jews lived in Leicester in the Middle Ages. It was only in the 19th century that their presence became more important. This was reinforced by the arrival of Jews from Russia at the turn of the 20th century.

One of the most important figures in Leicester was Israel Hart, who was mayor from 1884 to 1886 and from 1893 to 1894. He encouraged urban development with a fountain that became famous and especially a free library. Many places in the city pay homage to his work for the development of the city. Jews also participated in the development of the textile industry in the city and the region.

Historical synagogues of different streams

Another synagogue was built in 1898. The Leicester Hebrew Congregation reflects this expansion. It was built by the architect Arthur Wakerley. It is Orthodox and is still in operation. There is also a progressive synagogue in Leicester, whose community was founded in the late 1940s. It has been located since 1995 in a beautiful building dating from 1885.

A Jewish cemetery , dating from 1902, is the only one serving the needs of the community in Leicester and the surrounding villages. A great deal of effort has gone into cataloguing its 900 graves and putting the information online. It is divided into two parts, one of which is an old prayer house, the Tahara house, built in 1928.

The city’s Jewish population gradually declined in the second half of the 20th century. Thus, if they were more than 1000 in 1970, they were a little more than 400 at the beginning of the 21st century. Among the members, there was a large presence of university students. Leicester’s Jewish community is made up of around 800 people.

In 2022, as part of its 120th anniversary celebrations, the Hebrew Congregation synagogue opened a Jewish Heritage Centre, welcoming people of all faiths and cultures in a spirit of sharing, in order to raise awareness of Judaism. This has been made possible with the help of National Lottery funding.

The Jewish presence in Exeter is very old, dating back to at least the 12th century, and at the time of the expulsion of the Jews in 1290, about 40 families lived there. During the gradual return of the Jews a few centuries later, Italian Jews made up a significant part of the community.

The Exeter synagogue dates from 1763. This makes it one of the oldest synagogues still standing in England. Restoration work was undertaken in 1998 and again in 2013 on the synagogue’s 250th anniversary. It was located in a discreet corner of the city as was customary at the time.

A beautiful and ancient synagogue

It is Orthodox in style and its aron is made of wood. There was a heder adjacent to the synagogue until the 1960s. A Jewish cemetery is located on Magdalen Road and dates from 1757.

Currently, few Jews live in Exeter. Most of them are university students.

In 2018, the synagogue was the victim of an anti-Semitic attack, when an individual tried to set it on fire. An outpouring of cross-cultural solidarity ensued. The synagogue was closed for months while repairs were made. The synagogue is still a very popular place because of its age and the religious and cultural events it organizes.

Jewish students at the University of Exeter have experienced a sharp rise in anti-Semitism since the pogrom of 7 October. Strong pressure and threats from militant associations and a feeling of abandonment by the rector’s office have caused growing fears during these two years of war between Israel and Hamas.

The Jewish presence in Bradford seems to date back to the 19th century; at least the documents attest to it. Mostly Jews from Germany, attracted by the industrial development of the city’s textile industry. Bradford was one of the world’s wool capitals at the time. Migration from Russia during the pogroms and political upheavals in the country at the turn of the century strengthened Bradford’s Jewish population, as it did in other parts of England and Western Europe.

The first synagogue built in 1880 was a Liberal one. Built in the Victorian Moorish style, it has rather original architecture. It’s the second oldest Liberal synagogue in the country, after London’s. One of the great personalities of the community was Rabbi Joseph Strauss, who led the synagogue until 1922.

A pluricultural struggle to save a synagogue

The successful integration of Bradford’s Jews was evidenced by their active participation in the life of the city, both cultural and political. From the artist William Rothenstein to the poet Humbert Wolfe to Mayor Jacob Moser. This, despite the low percentage of Jews in the general population.

An Orthodox synagogue was also built in 1906, and relocated in 1970, but had to close in 2012. The Jewish population declined at the end of the 20th century and has stabilized today at a few hundred people.

Today, only the Liberal synagogue remains in operation in Bradford, welcoming visitors on shabbath and major moments of the Jewish calendar. The synagogue was actually saved financially by the participation of other faiths, Christians and Muslims.

The Jews were buried in sections located in two cemeteries. First the one in Undercliffe , then the one in Scholemoor .

A document attesting to the ratification of a decision authorizing the settlement of Jewish families in the region attests to its presence in 1671. A community was established around 1730, and the first synagogue was opened in the middle of the century. It was located on Ebraer Street.

Visiting Albert Einstein’s House

A new synagogue was opened in 1903. Among the city’s famous residents was Albert Einstein. His summer residence is a place that attracts many tourists.

During the Holocaust, synagogues were destroyed and the population persecuted.

Many Russian Jews settled in Potsdam after the fall of the Berlin Wall. Some 1000 Jews from that country resided in the city at the turn of the century.

Among the contemporary Jewish cultural heritage sites in the city is the Moses Mendelssohn European Center for Jewish Studies .

Futuristic synagogue

In 2021, a new synagogue was inaugurated. It has a very original futuristic architectural style for this type of establishment. It is part of the European Center for Jewish Learning that was opened at the University of Potsdam.

It has a limited capacity and can accommodate about 40 worshippers. A rabbinical school is also part of this new project. The inauguration took place in the presence of German President Frank-Walter Steinmeier. This university partnership is the result of the growing interest in Jewish studies among the general population.

Traces of Jewish presence in Munich date back to at least the 13th century. The Jews had a synagogue and a mikve.

During the next four centuries, Jews were alternately welcomed and more regularly excluded from Bavaria, depending on the rulers in power and accusations of ritual crimes, and their places of worship were destroyed. Only a few Jews remained in Munich.

Development of the Jewish community

It was not until the beginning of the 19th century that the situation improved for Munich’s Jews. At the turn of the century, 150 Jews remained. They were gradually integrated into the city and allowed to participate in civic and commercial activities. The arrival of Jews from Eastern Europe increased the number.

The rise of Nazism put an end to this development. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, disenfranchisement and violence against Jews accelerated. At the same time, the exodus of some of Munich’s 10,000 Jews was accelerated. Between 1933 and 1938, one-third left the city. 4500 were deported, only 300 returned.

Reconstruction of Jewish life after the war

The few survivors tried to rebuild a community after the war. This community grew to 3500 members at the turn of the 1970s. In 1972, during the Olympic Games held in the city, Palestinian terrorists murdered 11 Israeli athletes.

A Jewish bookstore opened in 1982, and by the end of the decade, there were more than 4,000 Munich Jews. This number increased again, mainly due to the arrival of Jews from the former Soviet Union after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

The liberal synagogue Beth Shalom opened in 1995. A Jewish community center was opened in 2006, including a school, the Ohel Jakob synagogue, a library, and a museum.

One of the people responsible for the rebirth of Munich’s Jewish community was Charlotte Knobloch. As a child in hiding during the war and the daughter of a public prosecutor, she became the president of the Jewish community in Munich. She led the project to build the community center.

In 2025, the Central Council of Jews in Germany celebrated its 75th anniversary against a backdrop of rising anti-Semitism. In September, German Chancellor Friedrich Merz gave an emotional speech to mark the reopening of the Munich synagogue, denouncing the sharp rise in anti-Semitic acts in Germany. The Chancellor began his speech in Munich by greeting the many elderly members of the city’s Jewish community, including 92-year-old Charlotte Knobloch and 71-year-old Josef Schuster, President of the Central Council of Jews in Germany.

In 2025, the city has 9,500 Jewish residents, making it the second largest city in Germany.

The Jewish presence in Périgueux seems to date back at least to the 13th century, since Jews were expelled in 1302. This is evidenced by the Ancienne juiverie, known as rue Judaïque, located behind the Museum of Périgord.

The contemporary Jewish presence in Périgord is mainly the result of the settlement of Alsatian Jews in the town at the beginning of the Second World War.

A community centre was built in the 1960s, in the wake of the arrival of Jews from North Africa. The synagogue offers services with Ashkenazi and Sephardic rites.

A ceremony to commemorate the round-ups of 23-24 and 27 February 1943 took place in Périgueux on 23 February 2024. To mark the occasion, the town council honoured Resistance fighter Rolph Hammel, who played an active role in rescuing Jewish families during the Holocaust. A plaque was unveiled and the Gymnasium street was officially renamed Rolph Hammel street . During the ceremony, Delphine Labails, Mayor of Périgueux, recalled the career and republican values of this courageous man, founder of the Périgueux Jewish community.

Following the anti-Semitic act of cutting down the tree planted in memory of Ilan Halimi in Epinay-sur-Seine in August 2025, numerous trees were planted in his memory and to mark their involvement in the fight against anti-Semitism, which has been ravaging Europe since 7 October, and the exploitation of conflicts in the Middle East.

Thus, the Jewish community of Périgueux planted an olive tree on 11 September 2025 in the garden of the synagogue, following an organised ceremony. A plaque was also affixed.

Sources: Sud-Ouest, DDV, Licra magazine

The Jewish presence in Libourne seems to date at least from the 16th century, and was authenticated when the existence of a prayer room was mentioned in the rue de Périgueux in the 18th century. Nevertheless, the place of worship where the Jews met in the following century was in a house in the rue Lamothe.

In 1840, the Jewish population of Libourne was estimated at 77 out of a total population of 9714 inhabitants. The religious leaders were Jacob Lopez and Lazare Brunswick.

The inauguration of the Libourne synagogue dates from 1847. More precisely, it was inaugurated on the 3rd of September, the day of the celebration of Rosh Hashanah, during a service led by David Marx, Chief Rabbi of Bordeaux.

Closed in 1912, the synagogue remained closed most of the time, especially during the Second World War. The Torah scrolls were kept in a house in Bordeaux and then returned in 1950.

Following the arrival of Jews from North Africa in the 1960s, the synagogue was reopened in 1962.

Every 10 January in Libourne, a commemoration ceremony pays tribute to the 60 Jews from Libourne deported during the roundup on 10 January 1944. The 2023 ceremony was attended by Yonathan Arfi, President of the Crif, who came to support the work of remembrance carried out since 2004 by the Souvenir de Myriam Errera association. The association was set up by the cousins of the 17-year-old Libournaise girl who was rounded up.

The town of Peyrehorade welcomed Marranos in the 16th century. Following the acquisition of land in 1628 from the Lords of Aspremont for a Jewish cemetery , these descendants of Portuguese merchants settled in a community.

However, following the expulsion of 1648, many families left Peyrehorade and by the end of the century there were only about fifteen Jewish families left.

However, this number increased again in the 18th century. The town had a synagogue since the 1720s, a second cemetery and a mikveh. A third cemetery was acquired in 1826. A time when the Jews left the town again. The synagogue was sold in 1898 and its ritual objects incorporated into the synagogues of Bayonne and Bordeaux.