The presence of Limoges Jews seems to date back at least to the 10th century, when persecutions are mentioned in texts from that period, including those of the author Adhémar de Chabannes. Among the Jewish personalities of the Middle Ages, Rabbi Isaac of Limoges.

Many Alsatian Jews found refuge in Limoges during the war. The contemporary Jewish community was formed after the war and reached a number of more than 600 people at the turn of the 1970s, but gradually saw the departure of many young people.

Due to the large number of antisemitic attacks since the beginning of the 21st century, the Jewish community in Limoges, which consisted of few families, attracted the settlement of Jews from the region of Ile-de-France living in areas where they felt threatened. Today, the Limousin Jews have a synagogue and represent a little less than one hundred families.

In August 2024, the Résistance Museum in Limoges received an exceptional donation from the family of Szaja Szarfsztejn, the last Jew to be murdered just before the city’s Liberation. The donation consisted of documents that make it possible to retrace his life, including his wallet, photographs and personal letters. These items were initially found hidden in the courtyard of the Gestapo headquarters in Limoges. Born in Poland, Szaja Szarfsztejn came to France in 1929 at the age of 24. Hiding with his wife during the Holocaust, after his daughter had been taken into hiding in a convent, he was arrested in Brive in June 1944 and transferred to Limoges, where he was tortured and murdered.

In March 2025, Righteous Among the Nations and Holocaust survivors gathered at Limoges City Hall for European Day of Remembrance for the Righteous. On this occasion, a book published by the Claims Conference was presented, containing the testimonies of 36 Righteous Among the Nations.

In July 2025, a family of Righteous was honoured in Limoges for saving a Jewish couple in 1943. Adolphe and Léonie Fargeaud received this medal posthumously for hiding the Morhange family in their home on Avenue Baudin.

Sources: France 3, France Bleu, Times of Israel

The Jewish presence in Bidache seems to date from the 17th century with the arrival of Marranos from Spain and Portugal. They benefited from the protection of the Duke of Gramont.

Although there was no significant Jewish presence after the Revolution, there is still a Jewish cemetery outside the town in Aquitaine.

Built in the 1660s, it is located on the Route du Port. It contains about a hundred graves dating from the mid-17th to mid-18th centuries.

The Jewish presence in Angoulême dates from at least the 13th century. A letter from the Pope in 1236 to the bishop of Angoulême attests to the violence suffered by the Jews during the Crusades.

The old synagogue was located near the Place Marengo and the Jewish cemetery between the abbey and the city walls. Rue Raymond-Audour used to be called Rue des Juifs, a place where many Jews seemed to live in the Middle Ages.

In 2014, a cenotaph was inaugurated in memory of the Jewish victims of the Shoah in Moselle. On this occasion, the city of Angoulême inaugurated the Jewish square in the Bardines cemetery , where this cenotaph and other old graves are located.

The Jewish community of Vevey was founded in 1904, thanks to the support of the former German consul Noelting. This man donated objects of worship and funds for the purchase of land, which in 1908 became the Vassin cemetery in La Tour-de-Peilz. A cemetery with 400 graves.

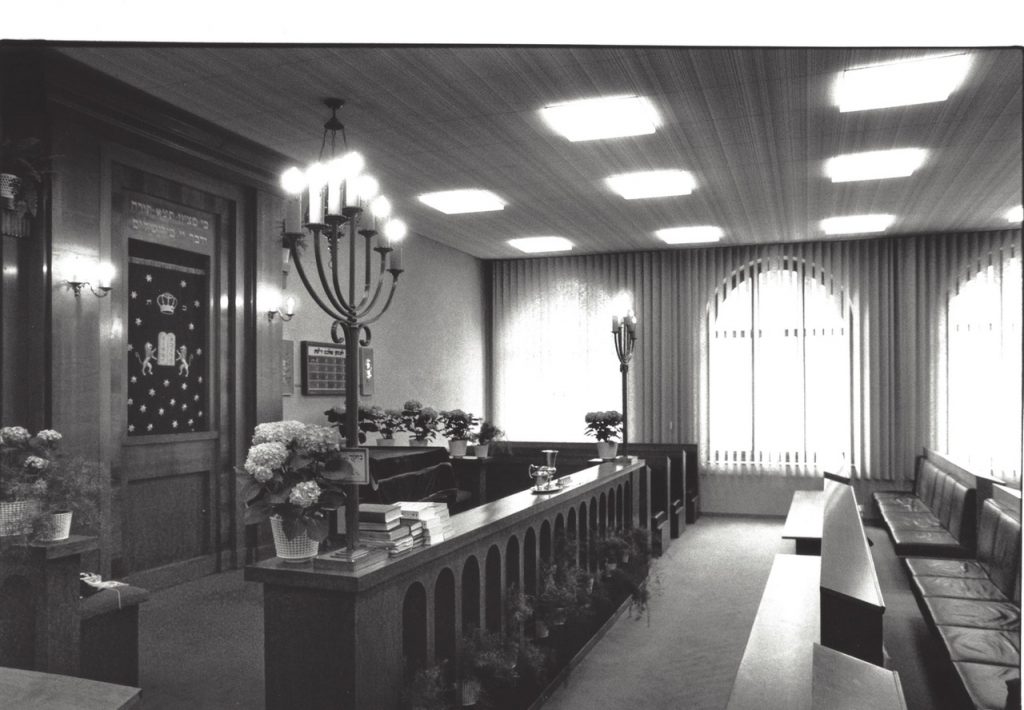

The Hôtel d’Angleterre houses a synagogue, a school, and a meeting room. The hotel was demolished in 1946. For the next eight years, prayers were held in a hall on Simplon Street. The synagogue was inaugurated in 1954, decorated with objects from the former places of worship and stained-glass windows by Régine Heim. That same year, the communities of Montreux and Vevey merged.

In 1917 there were 92 Jews in Vevey, but by 1990 there were almost 300.

The Jewish presence in Lucerne probably dates from the 13th century. During the Middle Ages, as in many other towns in the region, the situation of the Jews varied between welcome, persecution and expulsion, depending on the power in place. In the wave of major expulsions that took place between the end of the 14th and the end of the 15th century, the Lucerne Jews were expelled in 1384.

At the beginning of the 19th century, the Jewish community was re-established in Lucerne. There was a place of worship, a mikve, a school and social associations.

In 1912 the Lucerne synagogue was built with the support of Josef Croner, a resident of Karlsruhe who was enthusiastic about the city and the community. It was designed by the architect Max Seckbach.

While many people found refuge in the interwar period and during the Holocaust, the Jewish population declined in the second half of the 20th century, mainly to other cities in the country.

In 2025, there are about 40 Jewish families in Lucerne.

The Jewish presence in Fribourg probably dates from the 13th century. Jews were present in the Fribourg region, whether in Murten, Châtel-Saint-Denis or Romont.

During the Middle Ages, as in many other towns in the region, the situation of the Jews varied between welcome, persecution, and expulsion, depending on the power in place. In the wave of great expulsions that took place between the end of the 14th and the end of the 15th century, the Jews of Fribourg were expelled in 1428, then again in 1463 and 1481, the first two expulsions being partial. During the third expulsion, Fribourg became part of the Swiss Confederation.

Until the middle of the 19th century, the presence of Jews was only allowed temporarily, through fairs or other commercial relations that did not require a long stay. From 1860 onwards, Jews resettled there, mainly from the French region of Alsace.

The Jewish community became organised from 1895. For two years, a room on the Place Georges-Python was used as a place of worship. In 1904, the synagogue was inaugurated. At that time, part of the Fribourg cemetery was used by the Jewish community.

Over the course of the century, Jews moved into different spheres of active life. Previously confined to the professions of traders and cattlebreeders, they diversified into commerce, printing, medicine, and other liberal professions.

In the 1990s, the number of Fribourg Jews reached 40 families.

Interview of Claude Nordmann, President of the Jewish Community of Fribourg

Jguideeurope: How was the Freiburg synagogue built and did it change architecturally?

Claude Nordmann: The synagogue in Fribourg was built in an old house where dance classes were held. It was transformed at the beginning of the 20th century and underwent two restorations around 1939 and 1965. Since then, simple improvements have been made.

Which people have marked the Jewish history of Fribourg?

The Jewish Community of Fribourg (CIF) was founded in 1895 by Grand Rabbi Wertheimer of Geneva. It had many members from Alsace, including several cattle merchants.

There were no particular personalities who left their mark on Jewish history in Fribourg. However, we should mention Jean Nordmann, who was president of the CIF from 1957 to 1986 and who developed relations with the religious authorities of the Canton and other religious authorities. He worked for the recognition of the CIF as a corporation under public law in 1990, which put it on the same footing as the Catholic and Reformed churches. Jean Nordmann was president of the Swiss Federation of Jewish Communities from 1973 to 1980.

Another personality who taught in Fribourg, was the philosopher Emmanuel Levinas. He taught courses in Jewish thought and philosophy at the University of Fribourg in the 1980s and 1990s. He also gave the ICF the benefit of his erudition.

The East was home to both the city’s underprivileged social classes, victims of gentrification in other districts, and refugees from the continental conflicts of the 20th century: Armenians, Greeks and Jews. Between the 3rd, 11th and 19th centuries, the garment and shoe manufacturing industries developed, where many of these migrants were employed.

Before the war, Paris had 50,000 Jews from Eastern Europe, who constituted the vast majority of Parisian Jews until the 1970s. In the 1930s, most of them lived in different districts: the Marais, Belleville, La Roquette, Clignancourt and Saint-Gervais. These groupings were sometimes linked to their country of origin, religious practices and even political commitments.

In the 11th arrondissement neighbourhood of La Roquette, Jews from the Ottoman Empire, mainly from the regions of present-day Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria, settled at the beginning of the 20th century.

They settled for the most part between Place Voltaire, Rue Sedaine, Rue Popincourt and Rue de la Roquette. They worked mainly in textiles and lingerie and met regularly in cafés, including the famous Bosphore, and in small clubs.

The construction of the Don Isaac Abravanel synagogue was decided upon in order to promote the revival of Levantine Judaism, following the numerous deportations of the Shoah and the arrival of Jews from North Africa. A hundred metres away, on the Léon Blum square, stands a statue honouring the memory of the head of government who introduced paid holidays.

Built by the architect Alexandre Persitz, it was inaugurated in 1962 by Chief Rabbi Jacob Kaplan who saw in it the symbol of the link between tradition and modernity. Traits of this modernity are the facade divided into two levels, a courtyard preceding the synagogue behind the entrance gate, the sobriety of the religious motifs and the inscription in French of the 10 commandments.

During the Second World War, many Jews from the working-class neighbourhoods of the East joined the Resistance, including members of the Manouchian group and young people like Henri Krasucki.

A large fresco honours the courage of theManouchian group who led daring attacks against the Nazis and their Vichy servants before being captured and executed.

Numerous commemorative plaques recall the involvement of these Jews in the Resistance and the large number of Jewish children deported to this part of the city on the school grounds.

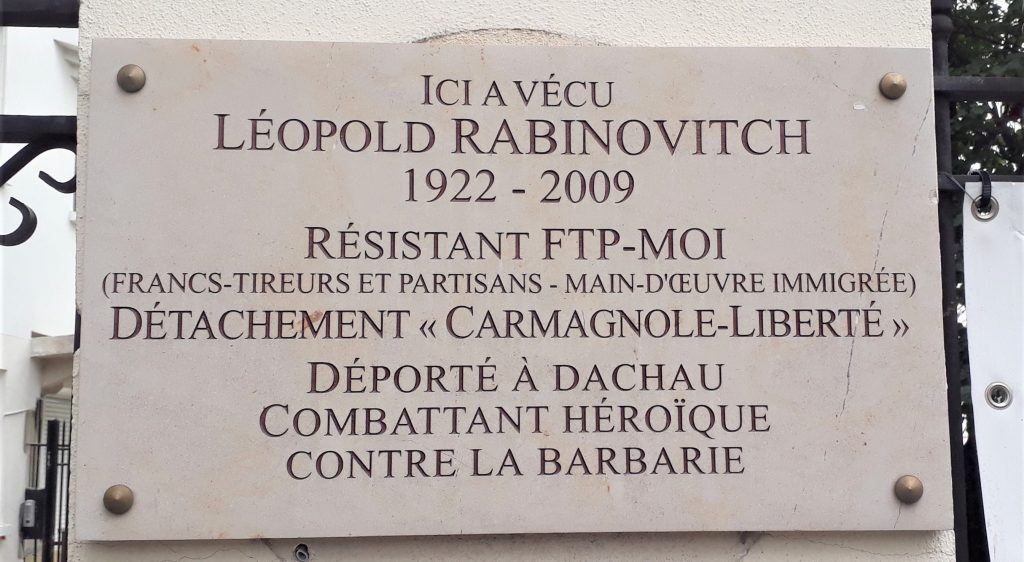

Among the places honouring these Resistance fighters are the statue of Marcel Rajman (member of the Manouchian group), Hélène Jakubowicz street and the plaque in memory of Léopold Rabinovitch .

Many Armenians from these neighbourhoods, whose families had experienced genocide a generation earlier, showed solidarity with the Jews, helping them to hide.

Another emblematic district of the working class environment is Belleville where many Jews live and work, diversifying by participating in all sorts of trades: grocery shops, cafés, newspapers… The Polish Jewish workers forming a large number of the workers in the fabric, leather and shoe industries, live in great precariousness.

After the war, because of the large number of deaths during the Shoah and the change in the area of migration, the Belleville neighbourhood gradually became an emblematic Tunisian Jewish neighbourhood, mainly from the working classes, like those from Eastern Europe before them. Many Tunisian restaurants, such as René & Gabin, grocery shops and places of worship opened in the 1960s.

Among the remaining synagogues in Belleville, the Pali Kao synagogue , inaugurated in 1930, should be noted first. Designed by the architects Germain Debré and Lucien Hesse, it represents the first modernist Jewish place of worship.

Modern because it favours the functional aspect allowing the place to serve both as a place of worship and culture. But also the few ancient motifs and the discretion of its façade. Both Ashkenazi and Sephardic rites are now performed in this place. Also in the neighbourhood, two synagogues dating from the 1960s, Or Hahaïm of Constantinian rite and Michkenot Yaacov of Tunisian rite.

Since 2000, following the sharp rise in anti-Semitic acts, many Jews have left the working-class neighbourhoods of eastern Paris to find refuge in the 11th, 20th and surrounding areas of Saint-Mandé and Vincennes. There are small oratories near the Boulevard Voltaire between the place of the same name and the place de la Nation. But also cashers and restaurants.

Since the turn of the century, the growing success of the massortis and liberal communities in Paris, particularly in the East, should be noted. With the Dor Vador , JEM East and JEM Surmelin synagogues in the Gambetta district. Neighbourhood near the Père Lachaise Cemetery, where many great figures of French history are buried.

Near the allée Chantal Akerman , in the 20th arrondissement of Paris, one of the greatest filmmakers of all time lived from the age of 18. “My daughter from Ménilmontant”, as she is nicknamed by her mother Natalia in the book “A Family in Brussels”, is a dialogue of memories, stories and silences. Brussels and Paris devoted a major exhibition to her in 2024-5, and her films are still regularly shown in cinemas around the world.

Like Albert Cohen, she is the author of masterpieces in many different genres. The only difference, perhaps, is that she didn’t need to make “The Film of My Mother” when it was too late, since Natalia Akerman has been in the limelight right from the start of her daughter’s work.

An Auschwitz survivor, Natalia doesn’t talk about it, torn between the imminent need to hold on and rebuild and the Jewish resilience that consists of promising a better dawn for the next generation. All the while, she passes on her strength and dignity to her daughters Chantal and Sylviane.

From her father Jacob, they inherit humour, hard work and a willingness to dance through life and out of trouble. Jacob Akerman is a shopkeeper, owning a clothing factory in the Triangle district and a shop in the Toison d’Or gallery.

As for Brussels, it shares with the two young women born in the aftermath of the war, its bon vivant Belgian spirit, with its cartoon characters, glasses and stories all rounded off to facilitate boats overflowing with pleasure, inspiring in its own way so many stories with cheerfully spilled beers.

Chantal’s Polish maternal great-grandfather was on his way to the United States, trying to reach the port of Antwerp to embark. But like so many Jews, he realised just how happy life could be for a Jew in Belgium.

Chantal Akerman was born in Brussels in 1950. At the age of 15, she went to see Jean-Luc Godard’s “Pierrot le fou” at the cinema with her friend and future producer Marilyn Watelet, amused by the film’s title. It was a revelation and the birth of her ambition.

At the age of 18, she directed the short film “Saute ma ville”, earning the support of André Delvaux and Eric de Kuyper. The story of a teenager who locks herself in the kitchen and acts in increasingly incoherent ways, throwing everything away and shining her shoes and then her legs next to a Manischewitz box.

Chantal moved to Paris after the shoot, hoping to find inspiration there, which never left her in Paris, New York, Brussels, Tel Aviv, Germany, Eastern Europe and even on the Mexican-American border.

At the age of 23, she directed “Je, tu, il, elle” (I, you, he, she) with Niels Arestrup and Claire Wauthion, a tale of anxiety, wandering and the reunion of operatic bodies. Two years later, Chantal entered the big leagues once and for all with “Jeanne Dilman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles”. Delphine Seyrig leads an ultra-ordered life, covering up her silences and wounds, bringing up her son alone. A life without pleasure, until something unexpected happens. In 2022, this work was voted best film of all time in the ten-yearly rankings drawn up by “Sight and Sound”, the magazine of the British Film Institute.

In “Pierrot le fou”, Jean-Paul Belmondo asks Samuel Fuller to define cinema. The director replies that it was an emotional battlefield. Perhaps this is why Chantal Akerman is one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. Her camera presents love and humour, songs and silences, deep thoughts and nagging worries through a gaze that is both mischievous and gentle. Ahead of her time, ahead of our time too, between the reconstruction of a generation and their children’s quest for pleasure and self-assertion, who fear the return of the dark ages. Sylviane Akerman, Chantal’s sister, now preserves her memory, notably through a foundation.

The Jewish presence in Palermo dates back to Roman times. Documents found in the Genizah of Cairo attest to their presence in the Middle Ages. Some of them arrived as slaves during the period of Muslim domination. They were freed financially by their co-religionists. Nevertheless, the Jews managed to emancipate themselves and participate in the active life of the city during this domination, although they were subject to particularly heavy taxes.

Under the subsequent Norman rule, from 1072 onward, this unjust taxation remained. However, their rights as citizens were fully recognised. They worked in many sectors: fishing, crafts, dyeing, and silk, among others. They developed the silk industry extensively. According to Benjamin of Tudela, 1500 Jews lived in Palermo in 1172.

The development of the community continued despite religious pressures and accusations of blasphemy and the continuation of disproportionate taxes. In 1473, these accusations of blasphemy resulted in the trial and execution of several Jews. The following summer the Jews were attacked again.

When the expulsion of the Jews from Palermo was formalised in 1492, there were about 5,000 Jews in the city. Following the expulsion, just under 200 families of converts remained in Palermo. In the 18th century, the descendants of some of these Jews tried to resettle there.

However, very few Jews lived there in that period or in the two centuries that followed. A temporary synagogue was built by soldiers of the Allied troops who liberated the city during the Second World War.

Since 2013, Hanukkah has been celebrated in Palazzo Steri, the place where the authorities of the Inquisition were once housed. Many people were imprisoned and tortured there.

A mikveh was found in a courtyard of the Palazzo Marchesi , which was the seat of the Inquisition in the 16th century. Hebrew inscriptions have also appeared in the Palazzo Chiaramonte-Steri , which served as the seat of the ecclesiastical court and prisons.

In 2018, the Archdiocese of Palermo donated a building to the city’s Jewish community, the Oratory of Santa Maria del Sabato. The building is located in the complex of the monastery of San Nicola da Tolentino, in the heart of Vicolo Meschita, the old Jewish quarter of Palermo. The community was allowed to rebuild a synagogue there.

The ancient synagogue of Palermo was particularly beautiful, according to observers, and was located nearby. The Archbishop of Palermo Corrado Lorefice was honoured with the Wallenberg Medal for having enabled the rebirth of the Jewish community of Palermo with this donation, as well as for his promotion of interreligious dialogue.

The Jewish presence in Catania seems to date from at least the 4th century, as attested by a tomb from 383. During the Middle Ages, there were two Jewish quarters in the city, each with a synagogue. The first was located in the heights of Montevergine, the second in the lower part of the city. Nevertheless, the Jews were not confined to these quarters and were gradually able to participate in the active life of Catania like all other citizens.

This emancipation was particularly significant at the beginning of the 15th century, when 200 Jewish families lived there. Documents from this period show the variety of activities open to the Jews in administration, agriculture, medicine and trade. They lived mainly in two neighbourhoods: Judeca Suprena (located between the Bastione degli Infretti and the Bastione del Tindaro) and Judeca Suctana (located along the Amenano River). Each district had its own synagogue.

Nevertheless, until 1466, the Jews were subjected to a much higher level of taxation than the other inhabitants. Despite a relative appeasement, the threats of the Inquisition and its implementation in 1492 brought about the end of Jewish life in Catania.

At the beginning of the 16th century the remaining Marranos in the city, about 40 people, were protected by the political authorities. The traces of this heritage were destroyed at the end of the 17th century by the eruption of Mount Etna and an earthquake.

Two plaques have been placed in memory of the Jewish presence in the city. The first is in the Senate Palace. It was placed on the first anniversary of the expulsion from Sicily. The second was placed in the Cathedral of Catania .

A tomb found in the city of Agrigento attests to the Jewish presence since antiquity. Letters found in the Genizah of Cairo mention this presence in the 11th century. In the Middle Ages, Jews were subjected to church taxes and restricted in their practice. Fundraising was forced, especially to equip the King’s troops.

Among the most prominent figures of the time was Faraj da Agrigento, one of the main translators of Charles of Anjou. Jewish schools were also under pressure in the content of their teaching. Following the Inquisition, Jewish life did not resume in Agrigento.

In 2016, a Garden of the Righteous was inaugurated in Agrigento, in the heart of the Valley of the Temples.

The Jewish presence in the city of Cremona dates back to at least the 13th century. The Jews were allowed to settle there and not to be limited to small professional activities. Thus, they also became farmers and merchants, just like the other inhabitants of the city. This development allowed them to become the largest Jewish community in Lombardy in the 15th century.

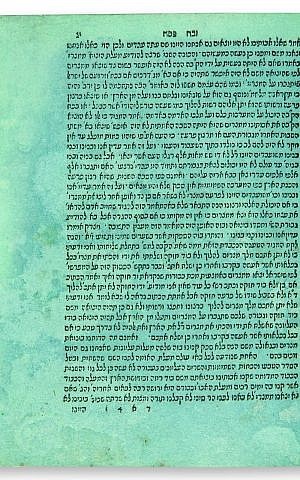

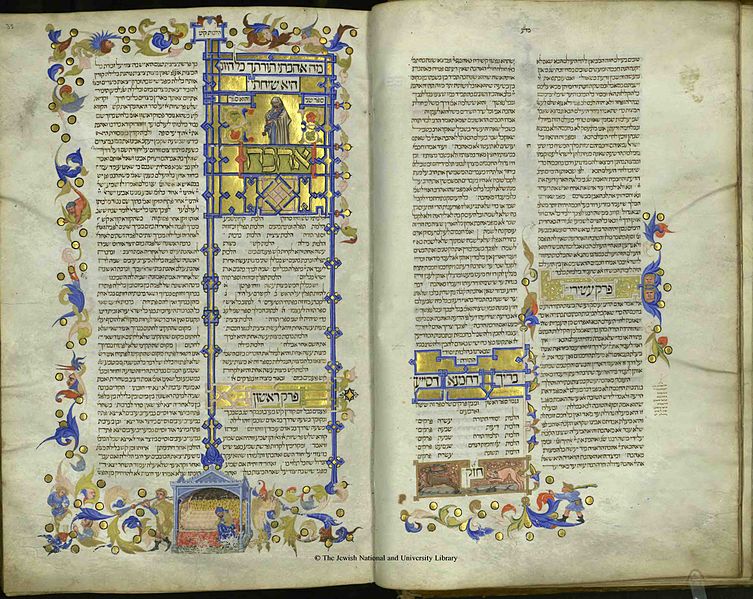

Victims of political and religious threats, the authorities also defended them during the 15th and 16th centuries. Cremona therefore quickly became a Centre of Jewish studies of the first importance. One of the well-known figures was Rabbi Joseph Ottolenghi. A Talmudic academy and a printing house contributed to this development. About forty different books were published, among them the Zohar in 1559.

Nevertheless, at the end of the century, 12,000 Talmuds and 10,000 Hebrew books were burned by the Inquisition. If 456 people lived in Cremona in 1590, only one family remained in 1629. The community’s archives are preserved in the Montefiore Collection in London.

In 2016, the National Library of Israel purchased a valuable collection of old Italian manuscripts. Among them are works printed in Cremona, including the Sepher Zevach Pesach with commentaries by Isaac Abarbanel, dating from 1557. Some of these precious manuscripts were, however, sold at auctions to other institutions.

The Jewish presence in the city of Brescia seems to be quite old. Throughout the 15th century, they were alternately welcomed and expelled according to political and religious directives. Among the personalities of this century, we can note the presence of Gershom Soncino, printer of religious works, among which the Meshal Hakadmoni by Isaac ibn Sahula, the first illustrated Hebrew book.

The early 16th century was no more reassuring, as the Jews were once again the victims of attacks and expulsions. Nevertheless, when the city came under Venetian rule, they were allowed to return in 1519. Rabbi Joseph Castelfranco founded the famous yeshiva of Brescia. In 1572, Jews were expelled again and their return was only formalised in the 19th century. A synagogue was then built.

On 9 September 2016, the 80th anniversary of the Israel Philharmonic Orchestra was celebrated at the Teatro Grande di Brescia. The inaugural concert was conducted by the great Arturo Toscanini in December 1936. Toscanini had answered the call of its creation (even before the State’s independence) and played in a warehouse specially built for the occasion in Tel Aviv. In 2016, under the direction of Maestro Michele Bui, the same programme was presented to the public with pieces by Rossini, Brahms, Shubert, Bartholdy and Von Weber.

The Jewish presence in Reggio Emilia probably dates from the beginning of the 15th century. They benefited from the rather welcoming attitude of the local authorities. As the Duchies of Modena and Reggio remained independent when the Church took possession of the Duchy of Ferrara at the end of the 16th century, the Jews lived relatively free.

The ghetto was created quite late, in 1669. The Jews practised a wide variety of occupations, not usually limited to those permitted by the Church. The city also welcomed Jews fleeing the Spanish and Portuguese inquisition.

Although the city had nearly 1000 Jews at the beginning of the 19th century, this number gradually declined due to migration to the big cities and the victims of the Shoah.

The favourable reception and freedom allowed for development, particularly intellectual development with great Talmudic schools and activity in the cultural life of the city.

The synagogue of Reggio was restored in 2005. The city also has a Jewish cemetery , created in 1808, following the Napoleonic edict ordering the transfer of graves outside the city limits. Later, graves from the old cemetery were transferred to it.

Like the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, this cemetery is a piece of the city’s history. Among the people buried here are Rabbi Jacob Carmi, delegate to the Sanhedrin of Paris in 1806-7, Leopoldo Rava who fought in the War of Independence in 1867 or Senator Ulderico Levi, patron of the city.

At the Palazzo Carmi , where the State Archives are located, built by the family of the same name in 1849, the archives of Jewish life in Reggio Emilia can be found today.

The Jewish presence in the town of Ravenna seems to date back to the 3rd century. Settling mainly at the end of the Middle Ages, the Jews practised the trades of wine merchants and goldsmiths.

Following the takeover of the region by the papal authority, brutal measures were taken; a synagogue was burned, and Jews were attacked. Those who remained, were expelled, and returned during the 16th century were eventually placed in the ghetto near the present Via Luca Lunghi.

The Biblioteca Classense holds ancient Hebrew manuscripts, some of which were published in the 16th century. Among them is the Sefer Kol Bo, dating from 1525, printed by the workshop of Gershon Soncino of Rimini.

Near Ravenna, in Piangipane, there is a cemetery of the Allied troops . There are 34 graves of soldiers of the Jewish Brigade who fought for the liberation of the area.

An internment camp was opened during the Second World War near the village of Fossoli. Established by the Italian army in 1942, it served as a prison for Allied soldiers, mainly British.

Following the German occupation of the country and with the participation of local soldiers, the prisoners were deported to concentration camps. Within a few weeks, almost 1000 Jews were imprisoned there. In all, 5,000 prisoners were subsequently deported, half of them Jews.

From the time of its liberation until the 1960s, the Fossoli camp served as a place of refuge for refugees, foreigners and Italians fleeing from the neighbouring towns run by Tito’s regime.

In the 1980s and 1990s, the camp was transformed into a place of remembrance and a study centre dedicated to Primo Levi, who was imprisoned in the camp and deported.

As in many cities in the region, the Jewish presence developed in the late Middle Ages. Their presence in commercial and cultural circles grew relatively according to the policy applied to them by the political and religious authorities.

When the city of Cento, as well as the entire Duchy of Ferrara, came under papal jurisdiction, the Jews had to settle in a ghetto, which was formed mainly in the city centre in the 1630’s. In Via Provenzali and Via Malagodi, about a hundred Jews lived there.

A synagogue already existed before the establishment of the ghetto and was restored in the 19th century. Other places of Jewish study were established in the 17th century. The main professional activities of the Jews of Cento were different types of crafts, trade and banking.

Among the personalities originating from the town, it seems that the family of illustrious British Prime Minister Benjamin Disraeli was among them. The sociologist Leone Carpi was a citizen of the city in the 19th century.

Although the Jewish community did not recover after the war, in the last twenty years the Cento ghetto has been restored thanks to the efforts of the city, allowing the rediscovery of the traces of the city’s Jewish cultural heritage. The arch of the synagogue was transferred to the Israeli city of Netanya in 1954.

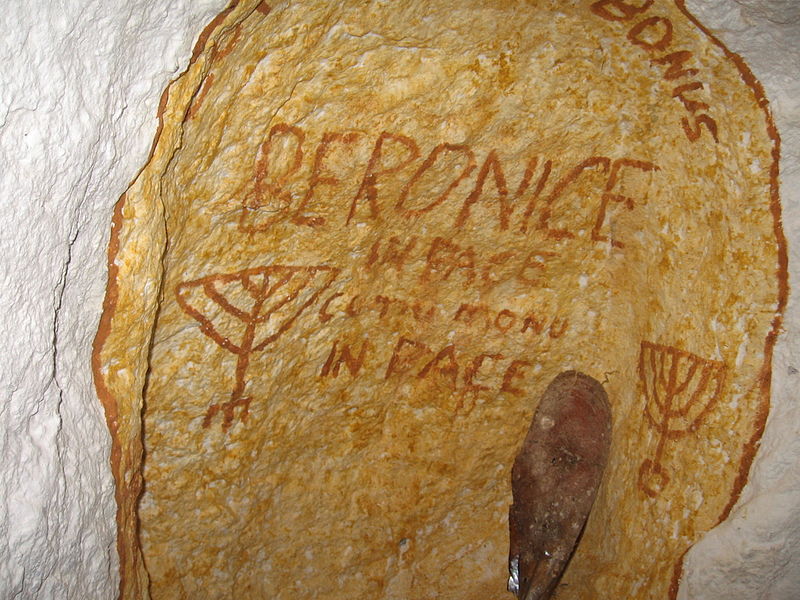

This small island located in the south of Sardinia is the home ofcatacombs which date back to Roman times. Among them, some have Hebrew inscriptions as was discovered by archaeologists in the area, or rather in Judeo-Latin, a language threatened with extinction.

The inscriptions in these catacombs seem to date from the 4th or 5th century. They are now accessible to visitors.

During the conquest of Sardinia by Peter IV of Aragon in the 14th century, Jews were part of the contingent of soldiers. Following the conquest, some settled there, joined in 1370 by Jewish families from Catalonia and France.

Nonetheless, the Jewish presence in Sardinia seems to date back at least two thousand years. A synagogue was built in Alghero in 1381. And a Jewish cemetery four years later. They participated in the economic and geographic development of the city, notably by financing its fortifications.

The good relations between the community and the regents of Aragon made it possible for the Jews not to suffer from the discriminations common at that time. However, following the application of the Inquisition’s measures at the end of the 15th century, their situation rapidly deteriorated, and they were expelled or forced to convert in 1492.

In 2013, the city’s mayor apologized to the Jewish community on behalf of the Jewish community for the fate inflicted during the Inquisition and invited them to return to the island. On this occasion, a Jewish Square was inaugurated on the site where the old synagogue stood.

The Jewish presence in this city located in the Ubria region in central Italy seems to date at least from the end of the 13th century. During the next century, they enjoyed equal citizenship rights and the community had a chance to prosper.

However, during the following centuries, according to the attitude of the various political and religious rulers both in the city and on a larger scale, this situation has become more complicated. There were still a few Jewish families living in Spoleto at the end of the 16th century, among them famous doctors. The Church St Gregorio della Sinagoga still commemorates the ancient presence of the Jews of Spoleto.

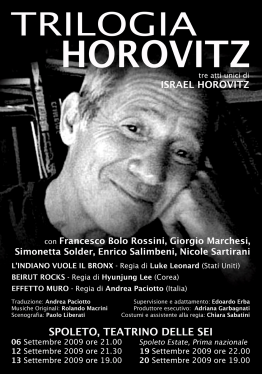

The author Israel Horovitz had one of his first international successes there when he presented the play the “Indian seeks the Bronx” in 1968, which featured on Broadway, with two comedians of Italian origin whom he first revealed on the New York stages, Al Pacino. and John Cazale ! Those united on stage and would eventually play together again on screen in the classic movie The Godfather, remembered for the roles of brothers Michael and Fredo Corleone.

Horovitz returned to Spoleto to thank the city for this early success and participated in a festival in 2009. That year, he presented plays focusing on racism and Middle Eastern tensions.

A local law dating from 1279 ordering the expulsion of the Jews from the city attests to their presence in this century in Perugia. A manuscript written in Hebrew from 1414 has been found, illustrated by local artist Matteo di Ser Cambio. In the 15th and 16th centuries, the Jews were expelled and then welcomed again, on several occasions.

One of the places in the city that attracted their visit was the University of Perugia, where they could study, some becoming famous doctors. Recently, cinematic footage from 1923 has been found showing the lives of two Jewish families from Perugia. We see in particular a wedding. They are probably the oldest images shot in Italy attesting to Jewish life.

This 9-minute film was screened in Rome and, above all, restored and digitized by state institutions. The original film was donated to the Jewish Documentation Center in Milan (CJDCF).

Administrative documents attesting to the Jewish presence since at least the 16th century. Texts referring to Jewish bankers and doctors working in the city.

Over time, these professions diversified, particularly in agriculture, silkworm cultivation and crafts. A synagogue was inaugurated in 1731. And four years later, the Jewish community bought land to place a cemetery .

Among the personalities of San Daniele, the long line of Luzzatto, originating in Venice in 1600 and whose members of the family will distinguish themselves along the centuries in various fields. Among them, Letizia Luzzatto, the poets Ephraïm and Isaac Luzzatto.

Following the expulsion from this Venetian territory in 1777, as the city did not have a ghetto, Jewish presence was prohibited there. At the beginning of the 20th century a small Jewish community was reconstituted in San Daniele.

The city was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire until the end of World War I, but heavily permeated by neighboring Italian culture. While the Jewish presence probably dates from the 13th century, recognition of it was not materialized by local authorities until the 16th century.

In 1696, a ghetto was erected in the city. During the following century, the Jews were authorized to practice various commercial activities like the manufacture of silk and wax, in particular by a branch of the great Italian family Morpurgo, which met with great success.

A synagogue was erected in 1756 on Via Ascoli. Following evictions from Venetian villages and the acquisition of rights to Austrian land at the end of the 18th century, the Jewish population of Gorizia totaled 270 people in 1788.

A stable figure, then which gradually increased at the end of the 19th century, reaching nearly 900 people.

The Mussolini regime and the racial laws applied caused the departure of many Jews, who numbered only 183 in 1938. Following the German invasion of 1943, 47 Jews were deported, of whom only two survived.

The very weak Jewish presence after the war encouraged the attachment of these for the celebration of festivals to the community of Trieste.

In 2025, an exhibition was presented at the Municipal Gallery of Contemporary Art in Monfalcone, as part of the European Days of Jewish Culture, to pay tribute to the poet Carlo Michelstaedter (1887-1910). He worked in particular on the persuasion of rhetoric. Drawings, texts and other biographical elements were shared with the public to show the involvement of Jewish artists and intellectuals in local cultural life at the beginning of the 20th century and their attachment to it.

During the city’s separation between Italy and post-war Yugoslavia, the Jewish cemetery remained on the Yugoslavian side. A new Jewish cemetery was opened later.

The Jewish presence in this city is attested since at least the 1st century BC on the epitaph concerning one of its inhabitants. Archaeological excavations carried out in the region have made it possible to find traces of Hebrew characters in buildings, mainly churches.

Nevertheless, despite such characters appearing in many churches, it could not be established whether it was previously a synagogue or not.

A stele has been found dating from 1140 with Hebrew inscriptions, and in this case, contrary to doubts about the buildings, it is indeed a Jewish tomb.

Among the characters from Aquileia, the family of the poet David ben Mordechaï Aboulafia should be noted.

The Genoese Jewish presence seems to date back to at least the 6th century, when Theodoric authorized the community to renovate a synagogue there, which was destroyed during actions by hostile locals. This presence was very limited in the Middle Ages, Benjamin of Tudela only noted the presence of two Jews, dyers from North Africa.

In the turn of the Spanish Inquisition, Jews were allowed to settle in Genoa and expelled several times throughout the 16th century. The same was true of their obligation to live in a ghetto, sometimes enforced vigorously, sometimes flexibly.

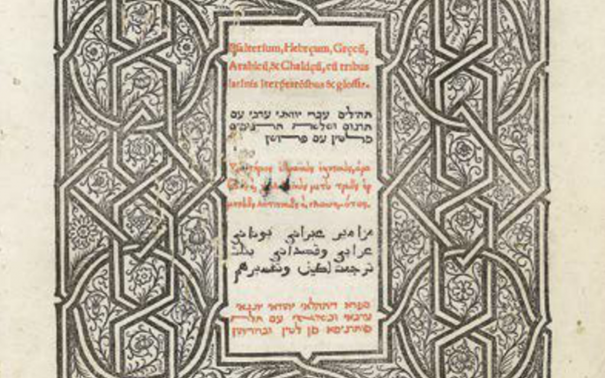

In 1516, the first bible in several languages was published in Genoa, mixing Hebrew, Greek, Latin, Aramaic and Arabic. It included footnotes on Christopher Columbus. His son complained to the authorities about his father’s description. They ordered the 2,000 printed books to be destroyed. A few copies survived this decree. One of these was sold at auction in New York in 2017.

If the Genoese Jewish population was only 70 in 1763, the equality in law granted in 1848, allowed this population to increase and to represent in these years nearly a thousand people.

A new synagogue was inaugurated in 1935 for the 2,500 Genoese Jews. As in the rest of Italy, they will be victims of the racial laws of 1938. Following this application and before the German occupation of the city in 1943, many Jews managed to flee. 238 Jews were deported, of which only 10 will survive.

At the end of the 19th century, a new Jewish cemetery was used and the tombs buried in the former one transferred there.

While the presence of Vesulian Jews has been documented since the 13th century, a community was formed there notably thanks to the synagogue located on the Grande-Rue.

About fifteen Jewish families lived in the city. If unlike other communities in the region, the Vesulian Jews were not particularly known for their yeshivot, some personalities played a historical role, like the banking family Héliot or Manessier de Vesoul who took part in the discussions. concerning the return of Jews to France in 1359. Jews were regularly accused of poisoning, according to a frequent spread of anti-Semitic rumors at the time.

A small Jewish community was born again following the wave of emancipation caused by the French Revolution, reinforced by the arrival of Alsatians after the war of 1870. Among them, the great rabbis Isaac Lévy and Moïse Schuhl.

Today you can find a synagogue dating back to 1875 as well as a Jewish cemetery built in the 19th century. During World War II, 107 Jews were deported from Haute-Saône. Mayor René Weil was forced to resign in 1940 and returned to his post after the Liberation of 1944. Raymond Aubrac, famous resistance member, was born in 1914 into a Jewish family in Vesoul. Vesulian Jews rebuilt the community after the war, but the synagogue is abandoned.

In 2023, Vesoul town council restored the town’s Jewish cemetery, which had been abandoned and closed to the public. Visits are now possible by contacting the local authorities. That same year, 35 final-year students at the Lycée Belin produced a booklet containing 30 biographies of people born between 1783 and 1933 and buried in the Jewish cemetery in Vesoul.

Sources : l’Est Républicain

The presence of Mâcon Jews has been documented since 820 during pressure against the Jews to convert. But their presence dates from at least the 6th century.

A good part of these were then wine growers. A Jewish quarter was located in Bourgneuf. The Ursulines Museum has medieval Jewish tombstones.

Following the expulsion of the Jews in 1394, a small community was finally able to rebuild there following the emancipation granted by the French Revolution.

On the eve of World War II there were only about fifty Jewish families from Mâcon. A synagogue was set up in 1962, for a growing community following the arrival of Jews from North Africa during that decade.

If the origin of the Jovignian Jews is not certain, its medieval presence is notably noted by the number of Tossafists who lived in the city in the 12th century.

Among them, Menahem Perez de Joigny and Yom Tov Ben Isaac de Joigny. Other eminent scholars followed before the expulsion of the 14th century.

The emancipation of the Jews of France through the French Revolution will not bring many Jews back to the city. Thus, Joigny listed 10 Jews in 1841. The Street of the Jews is the only vestige of this rich medieval cultural period.

The first documented traces of the presence of Dijon Jews date from the end of the 12th century.

They lived mainly on rue de la Petite-Juiverie, currently called rue Piron , rue des Juifs, currently rue Buffon and rue de la Grande-Juiverie, currently rue Charrue . The synagogue was on the first of these streets. A Jewish cemetery was located in what is now rue Berlier. About fifty Jewish tumular stones were discovered there between 1885 and 1900.

There were famous Jewish doctors in the Middle Ages, including Solomon of Baûme and Elie Sabbat. The 14th century saw a series of expulsions and reintegration, as in other cities of France, ending with an expulsion in 1394.

The emancipation granted by the French Revolution allowed the Jews to return to these lands, an overwhelming majority of Jews of Alsatian origin. The Jewish population thus went from 50 families at the turn of the 19th century to 400 individuals at the beginning of the 20th century.

The current neo-Byzantine style synagogue was built by the architect Alfred Sirodot in the 1870s, replacing the too small one on rue des Champs.

A large part of the 376 Dijon Jews identified in 1941 and resistance fighters in the city were victims of the Shoah. Among them, Rabbi Elie Cyper, prisoner of war in 1939 who escaped and joined the Resistance, captain of FFI in particular in Périgueux, who was deported and murdered in Lithuania in 1944. Help from the population of Dijon and smuggling networks allowed half of Dijon’s Jews to flee south.

In the aftermath of the war, the community was rebuilt thanks to the arrival of Jews from North Africa and Alsace.

In May 2024, the city of Dijon paid tribute to those arrested and then deported during the roundup of 26 February 1942, by inaugurating three memorial paving stones. The descendants of the eleven deportees took part in the ceremony. The project was led by a contemporary history teacher at the Lycée International Charles de Gaulle. His pupils had helped him research the victims of the roundup, making this tribute possible.

The presence of Chalonnais Jews dates to at least the 9th century, according to period documents relating to forced conversions. Some dating from the 12th century evoke the profession of winegrower exercised in particular by Jews from Chalon.

The Jewish community had a cemetery located on what is now rue des Places and a mikvah in Saint-Jean-des-Vignes. Rue des Juifs was located on what is now Grand’rue. Talmudist Eliezer ben Yehuda lived there in the 11th century.

Following the expulsions of the 14th century, Chalonnais Jews were allowed to resettle there until the expulsion of 1394. The emancipation granted by the French Revolution allowed the Jews to return to Chalon-sur-Saône as in other communes of France and the community was officially established there in 1871, thanks in particular to the arrival of Jews from Alsace-Lorraine. The synagogue was inaugurated in 1882. Since the end of the 1960s, around a hundred Chalonnais Jews have lived in the city and its surroundings.

During the commemoration of the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz camp, at the end of January 2025, pupils from the Lycée Agricole de Fontaines worked for a week on this theme. They did this in coordination with the town hall, in particular through meetings and a visit to the synagogue in Chalon-sur-Saône. Welcomed by the Jewish community, the pupils were able to gain a better understanding of issues relating to the religion, culture, and history of Judaism and to discuss subjects such as tolerance and the fight against discrimination.

The Jewish presence in Besançon seems to date from the 1st century; at least it is attested to the time by official documents.

The Jewish quarter was historically around the Doubs river. Rue Juive was located on what is now Rue Richebourg . The Jewish cemetery was located opposite the Porte de Charmont.

The Bisontine Jews were expelled in the 15th century. They were allowed to do this very sparingly.

Following the emancipation of the Jews by the French Revolution, the Bisontine Jewish community settled there again. About twenty families formed it in 1807.

The current synagogue , in Moorish style according to the architect Pierre Marnotte, was inaugurated in 1869. It succeeds another synagogue built on rue de la Madeleine, in the Battant district in 1831, which became too small to accommodate the faithful.

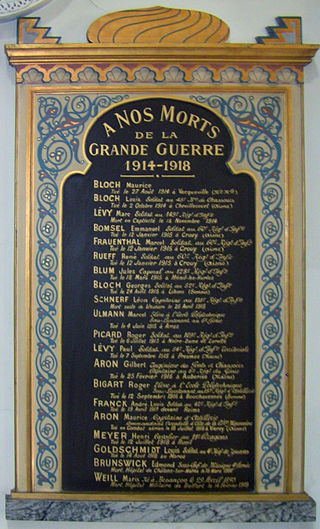

The arrival of Jews from Alsace-Lorraine following the war of 1870 allowed an increase in the community. 763 Bisontine Jews were recorded by the Consistory in 1897. 20 Bisontine Jewish soldiers died with weapons in hand during the First World War, as recalled by a monument at the entrance to the city’s Jewish cemetery .

Although 170 Bisontine Jewish families lived in the city at the start of the 20th century, thanks in particular to the arrival of refugees from the Russian revolutions and the rise of anti-Semitism in Germany, the Holocaust claimed many lives in Besançon.

The community found a new lease of life with the arrival of Jews from North Africa in the 1960s. The Jérôme Cahen Center (named after the city’s former rabbi) was opened in the 1970s and organizes numerous events related to Jewish culture.