The city bears the name of Bagnos (“small bath”) which will be completed in Baigneux-les-Juifs following the arrival of many Jews in this new agglomeration.

The Jewish presence seems to date from the 13th century. The medieval synagogue was located rue Vergier-au-Duc .

However, as in many other places in France in the end of the Middle Ages, the Jews were expelled from the city.

The presence of Auxerre Jews in the capital of Yonne is attested by a letter from Rashi to the Talmudists in the region.

One of the Jewish quarters was near Porte Féchelle. The old rue du Puits des Juifs is now rue du Pont .

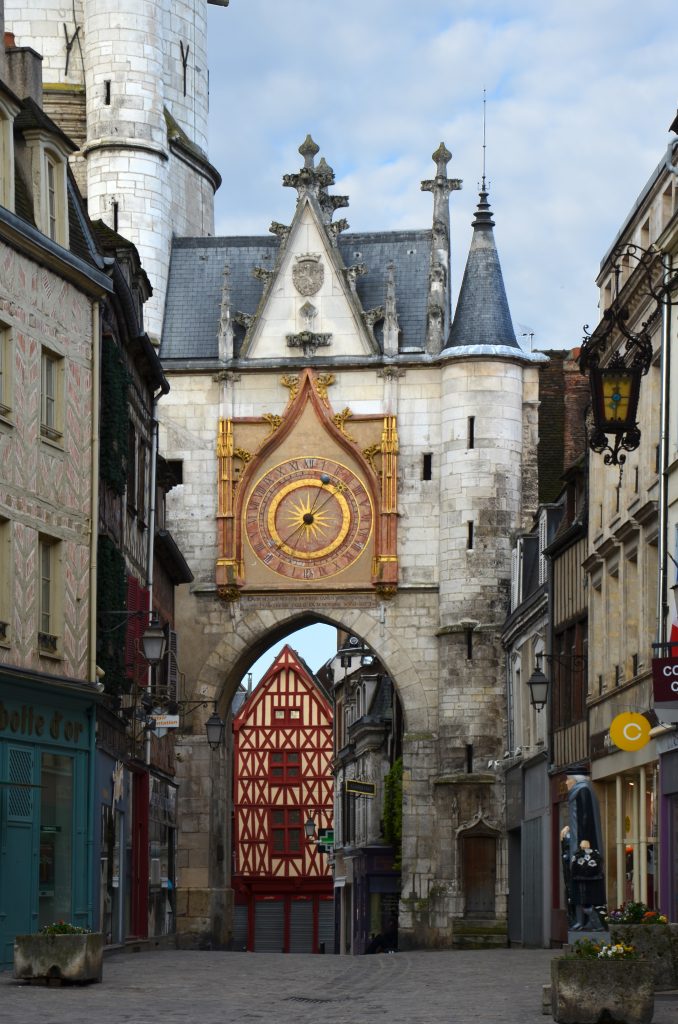

A stone on a wall of the Clock Tower contains a Hebrew inscription. Jews were expelled from the city several times between 1184 and 1393.

The Auxerre Jews will once again be part of the city with the wind of emancipation from the French Revolution. However, there were only 70 Jews on the eve of World War II.

Numerous epigraphic traces attest to the presence of Jews in Pompeii before the city was destroyed by the volcanic eruption of Vesuvius in 79. They also lived in the towns near Herculaneum and Stabia.

Names of Jewish personalities have been found, such as Fabius Eupor and Youdaikos. Historian Flavius Joseph mentions that a descendant of King Herod died during the eruption.

In the ruins of Pompeii was found a house nicknamed by archaeologists “Casa degli ebrei”. It is found in this place: N.6, Reg. VIII, Ins. 6. Murals depict the Judgment of King Solomon. Nevertheless, the work being a bit caricatural in relation to the subject, doubts remain about the origin of the work and the affiliation of the house. There is also an inscription “Sodom Gomor” on ruins located at N. 26, Reg. IX, Ins. I. Other designs such as a five-pointed star have been found.

All these works do not constitute proof and stimulate many debates among historians. The tourism enhancement of Jewish cultural heritage at the site should therefore be taken with a grain of salt, as debates about its authenticity are far from resolved.

The Jewish presence in Capua appears to date from the end of the Roman Empire. The ancestors of the liturgical poet Ahimaatz ben Paltiel lived in this city, occupying important roles in the financial management of Capua. According to Benjamin de Tudèle, who passed there, 300 Jews lived there in the middle of the 12th century.

Between this period and the 15th century, Jews engaged in other trades such as dyeing and medicine. Despite relative freedom, they also underwent forced conversions.

The city received refugees from the Spanish Inquisition at the turn of the 16th century, but the community of Capua was also forced to leave the city a few years later.

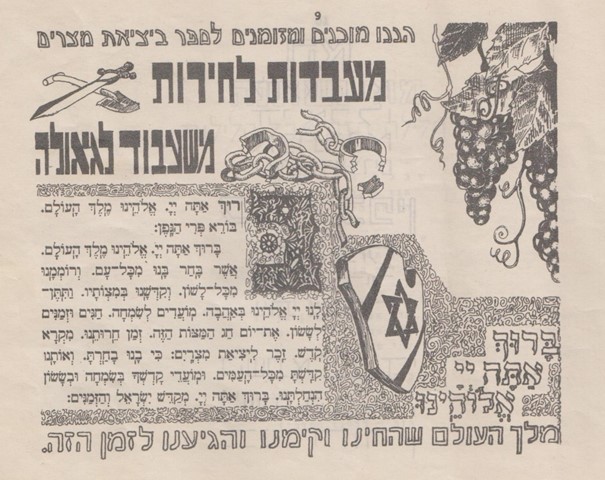

In 1946, Israeli soldiers, members of the Jewish Brigade serving under the British flag during World War II, were stationed in the city waiting to be able to return.

A specially written Passover Haggadah was found. They took part in helping Holocaust refugees and in hunting down the Nazis. The Haggadah was featured among others from this era in an exhibition at the National Library of Israel in 2018.

It seems that the Jewish presence in Benevento dates back to at least the 5th century. A yeshiva was established there in the 11th century by Hananeel ben Paltiel, a member of the family of the liturgical poet Ahimaatz ben Paltiel.

Benjamin of Tudela noted there the presence of 200 Jewish families. Which did not undergo the same expulsions from the Kingdom of Naples as the other communities, being under papal protection.

Graves with Hebrew inscriptions dating from the 12th century have been found in the city’s cemetery . Jews then worked mainly in the textile industry, and later in corn.

Nonetheless, expulsion was ordered in the 16th century by a Pope, in the 16th and 17th centuries, notably following spurious anti-Semitic accusations of well poisoning.

There has been no organized Jewish life in Benevento since, but the city has recently attracted Israeli migrants.

The first traces of the Jewish presence in Amalfi date back to the 10th century. Letters found in the genizah of Cairo attest to this in particular. This small community worked mainly in clothing and silk in particular. An international trade with exchanges in Egypt, hence the indications of these letters.

Benjamin de Tudèle mentions there the presence of about twenty families in 1159, including a Ben Paltiel, probable descendant of the poet Ahimaatz ben Paltiel. Forced conversions carried out in the Kingdom of Naples forced departures or renunciations of Judaism at the end of the 13th century. The small community that succeeded in reconstituting itself at the beginning of the 14th century had to leave the kingdom of Naples in 1541, like the rest of these.

A Jewish Cultural Center is currently trying to perpetuate itself in Amalfi.

The Jewish presence in Reggio seems to date from the 4th century. However, official documents tracing this presence date from the 12th century. As in various towns in the region, the Jews worked mainly in the field of silk and wool.

The first Hebrew books printed in Europe were printed in Reggio by Abraham Garton in 1475. The first Hebrew commentaries on the Hagaddah were also published there in 1482. There is still a via Giudecca today. Many Jews took refuge there after the Spanish Inquisition, before the city fell into their hands as well.

Ancient objects attesting to the Jewish presence in the city are kept at the National Museum of Archaeology of Reggio. Among them is an inscription in Greek on marble “Synagogue of the Jews” dating from the 4th century, an oil lamp with a menorah drawn on it, and bronze coins from the 5th century with a menorah.

In 2007, this small town in Calabria inaugurated the first synagogue opened in the region in 500 years. A project made possible thanks to the dedication of Barbara Aiello who was the first female rabbi in Italy, since 2004. Born in the United States, her family was originally from this city. Barbara Aiello’s father, who grew up there, participated as a soldier in the liberation of Buchenwald.

Since 2007, the Ner Tamid del Sud synagogue has welcomed many Jewish families from the region wishing to pray and celebrate holidays, bat and bat mitzvot, as well as weddings.

As the founder of the Italian Jewish Cultural Center of Calabria, which is located on the ground floor of the synagogue, Aiello helps the descendants of families forcibly converted during the Middle Ages to rediscover Judaism. This synagogue is currently the only one in operation in the Calabria region.

Our interview with Rabbi Barbara Aiello

Jguideeurope: You are originally from the region of Calabria. What motivated you to come back, build a synagogue and develop Judaism in the region?

Rabbi Barbara Aiello: My father. He was part of a crypto Judaic family, or as we say bnei anusim, the “children of the coerced ones”. His ancestors came from Toledo during the time of the persecution and the expulsion from Spain. They went to Lisbon, then Sicily, the Aeolian islands, then from the mainland of Italy into the mountains. My father felt that there was a rich Jewish history here. I was the first one in my family born in the United States. My father talked so much about this, I brought him back to Serrastretta, actually four times before he died in 1980. Each time he said: “There’s so much to be done here, and you can do it because you received a Jewish education”. Unfortunately, the people here have only bits and pieces of their traditions, and sometimes don’t even know those pieces are related to Judaism.

How did you reach out to them?

Many people ask why I chose Serrastretta for the first synagogue. In these little mountain towns, it’s hard to start anything new if you are unknown. My mother-in-law was the first woman doctor in Calabria and our family was well known. It was considered an honor to the town that someone from America would want to come back. I have a very unusual combination of skills: Italian and Hebrew. I could ascertain immediately various words that many people here believed were Italian mountain dialect but were actually Hebrew. For example, little crumbs on a table are called by Calabrians here ”hametz”. The “baita” is a little house that you build where you would stay to tend your crops. My great-grandfather, Saverio Scalise, who was the father of my grandmother, lead Hebrew prayers in the cantina of this house where I’m speaking you from. The synagogue is the building next door. Four times in the 1880s he went to study in Val-David, a little Hasidic settlement in Montreal. When he gathered people for prayer, it concerned the extended family. Not in public, it was too dangerous to be overt.

Is this revival of Jewish life linked more to a wish of discovering of embracing Jewish roots?

We are the first active synagogue in the whole area of Calabria in 500 years since the Inquisition and the first affiliate member of the Jewish Reconstructionist movement. We are open and welcoming to Jews of all backgrounds. That includes interfaith families, patrilineal descent, gay and lesbian couples. We extend a hand of Jewish welcome to everyone recapturing their roots, reconnecting culturally and spiritually. I say to my community that you can embrace or just discover your Jewish roots. In the Jewish cultural center of Calabria, we organize many events for our community. We just had a Festival in the region, featuring all the crafts and arts of many centuries ago. We participated by showing some of the elements of a Jewish wedding, putting up a huppah in the synagogue, where 600 people walked through, listening to your presentation. I’m also very involved with the Ferramonti camp, doing Rosh Hashanah there for the fourth year in a row. It looks like we’ll be doing Yom Kippur in Trani. We try to make our presence known all over the region.

Do you receive many genealogical research requests?

At least ten a week! The reason is that the immigration from Italy to America was primarily from Calabria and Sicily, the two poorest regions: 81%! And if indeed 50% of Calabrians and Sicilians prior to the Inquisition were Jewish, your chance of being Jewish in North America is greater than if you’re an Italian living in Italy. We have many visitors and a program which gives information about family surnames. We trace family surnames, if possible, back to Spain and where the name migrated on its way to Italy. Happy to have tourists; people can come and visit us by appointment, and we share with them the Jewish heritage of the region.

The Jewish presence in Catanzaro dates from the end of the 11th century. In 1073, Robert Guiscard, the Norman conqueror, invited them to develop silk weaving there. They allowed the city to become the hotspot of this specialty in Italy, popular throughout this region.

Benjamin of Tudela attested to the Jewish presence in it and its development. However, after two centuries of a relatively peaceful life, the charges and expulsions caused the departure of most of the region’s Jews, mainly to Greece.

The ancient synagogue of Catanzaro was transformed into a church dedicated to St. Stefano.

An exhibition dedicated to Chagall’s biblical interpretations will be presented at the San Giovanni Monumental Complex in Catanzaro in 2021. A total of 170 works accompanied by support materials will help visitors to better understand the artist’s link with Judaism, as well as the very ancient presence of Judaism in Calabria.

The Jewish presence in Venosa dates back to Roman times. Hebrew inscriptions have been found on site probably dating from the 3rd century. Funeral inscriptions present in Jewish catacombs have been discovered over time by archeological endeavors. These finds so far attest to 75 inscriptions present, but access to the catacombs has been complicated for a long time.

In particular at such sites to be seen in Venosa, there is a fresco adorning an arcosolium showing a menorah in the center which is surrounded by different religious elements such as an etrog, a lulav, a vial of oil and a shofar.

The chronicles of Ahimaaz ben Paltiel evoke the presence of an emissary from Jerusalem present in the 11th century in Venosa, land of numerous encounters and cultural exchanges. There, he met the Talmudist and poet Silano. Following the conquest of the Normans in 1041, Venosa lost its status as a center of Jewish studies.

In 2007, the Jewish catacombs of Venosa were opened to the public after major works were carried out. An official ceremony with local and regional authorities, as well as a conference at Pirro del Balzo Castle accompanied this event. Additional restoration work was carried out in the catacombs of Venosa in the early 2020s.

The Jewish presence in Aquila seems to date from the end of the 13th century. Ladislaus, the King of Naples, allowed two Jewish families to settle there and carry on business activities. Authorizations were issued and then withdrawn over the centuries according to the variable geometry leniency of political and religious leaders. Thus, in 1488, following particularly hostile sermons against them, only two Jewish families remained in the city. In 1511, the Jews were expelled from the kingdom of Naples, of which Aquila was then a part.

A few Jewish families relocated there in the 20th century. Following the earthquake of 2009, which had disastrous effects on the city, the Jewish communities of Italy, and that of Rome in particular, got involved in helping the victims.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

The Jewish presence in Uzhhorod probably dates from the 16th century and has been a recognized center of study for the presence of numerous rabbinical referents.

Intellectual growth

Among them, Solomon Ganzfried (1804-1886), author of the Kitsur Shulkhan Arokh, which is still considered today as a reference work. An intellectual development encouraged by a Hebrew printing press present since 1864, reflected by the different Orthodox and Hasidic movements and their written production, Jewish schools and yeshivoth.

In 1904, the beautiful synagogue of Uzhhorod was inaugurated. Built by architects Gyula Papp and Ferencs Szabolcs, it is constructed in a Neo-Byzantine style.

Expulsions and deportations

When the city came again under Hungarian control (which was the case prior to WWI) after the Munich accords and the German attack on Czechoslovakia, anti-Jewish measures were taken and Polish Jews were expelled to their homeland.

In 1944, a massive deportation to Auschwitz was organized in Transcarpathia. Thus, if in 1930 there were 7,357 Jews in Uzhhorod, after the expulsions and especially the deportations, only a few hundred returned to the city following the war.

Rebirth of Jewish life

In 1947, the neo-Byzantine style synagogue was transformed into a concert hall by the Soviet authorities. The building is intact, and a Beth Chabad now provides prayers there. The community of Oujhorod today centralizes Jewish activities for the towns of the region.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

The Jewish presence in Berehove probably dates from the end of the 18th century, when the city was part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire. Most of them come from Polish cities. In this period, Berehove already had a synagogue and a Jewish cemetery .

Numerous Holocaust victims

According to a census taken in 1921, 4,592 Jews lived in Berehove. A figure that numbered nearly 6,000 a few years later in 1941. They worked in a wide variety of fields: mills, vineyards, shops, medicine, and many others.

Following the Munich Agreement and the carving up of Czechoslovakia by Germany and its allies, the region came under Hungarian control. The Shoah was very brutal. Thus, after losing many rights, the Jews were deported en masse in 1944. 11,000 Jews were deported to Auschwitz, including 3,600 from Berehove.

Visiting the synagogues

In 1959, the main synagogue was closed by the Soviet authorities and turned into a theater. As was the case in other towns like Mukachevo, prayers were then held mostly in private apartments. The former Great Synagogue of Berehove is now a House of Culture. Its facade was covered with a drawn reproduction of the facade of the old synagogue.

While there were still more or less 300 Jews in Berehove in 1970, they are very few today. Nevertheless, a new synagogue opened its doors recently.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

This city of Transcarpathia, located at the crossroads of several nations with evolving borders has all the more been marked by many influences: Czech, Slovak, Polish, Austrian, Hungarian, Ukrainian …

The Jewish presence in Mukachevo, formerly known as Munkacs seems to date from the end of the 17th century. The first synagogue dates from 1768. Many religious currents were represented in the yeshivot, impregnated until the end of the 19th century by rabbis such Hayim Sofer and Shlomo Shapira. Furthermore helped by a recognition of rights by the local authorities and a good understanding between all populations.

Growth of Jewish culture

The Jewish community is very poor materially, most of the people being farmers or workers, but of remarkable intellectual wealth. Hasidism mingled with other Orthodox movements, but also Zionism and cultural Judaism. Three weekly newspapers in Yiddish were then published in Munkacs! The Yidishe shtime, the Yidishes folks-blat and the Yidishe tsaytung. And even a humorous newspaper, with the name slightly indicative of its function, Der Humorist.

Not only confined to studies, which proved an openness to the arts, an Orthodox Jew opened the city’s first cinema. Less entertaining but rather urgent, the city’s Jews repelled the assaults of Cossack troops in 1919.

During this period, the complex regional relations meant that the city was cut in two by the Czech and Romanian armies, requiring a passport to move from one side to the other. In 1920, the city became Czech, in accordance with the Treaty of Trianon, withdrawn from Hungary which ruled it until then. A little more than 5,000 Jews were counted in 1891, which constituted half of the total population. 10,000 Jews inhabited the city in 1920, in similar proportions.

A model progressive Jewish school

In 1925, the Hebrew Gymnasium of Munkacs was inaugurated. One of the most progressive Jewish high schools in Eastern Europe. Classical education was taught there, in Hebrew. Young women and men studied together and equally. An openness not always welcomed by some Orthodox representatives, threatening parents of students and teachers with excommunication. Tensions also existed between the various Orthodox movements.

Before World War II, Munkacs had the largest Jewish community in this region, with around 30 synagogues, mostly small shtiebels, and made up almost half of the population. The two main synagogues being the Bais Hakneses Hagadol and the Bais Medrash of the Munkacser Rebbes .

Destruction of the communities during the Holocaust

Taking advantage of the German invasion of Czechoslovakia, Hungary recaptured the city in 1939. Religious and cultural activity was drastically curtailed, and many Jews were sent to forced labor duties in the Hungarian army.

Following the German invasion on March 19, 1944, Jewish communities in and around the city were destroyed, with scores of Jews deported to Auschwitz. Among the 2,000 survivors (out of 15,000 Jews), Chaïm Kugel, the founder of the Hebrew Gymnasium of Munkacs. He immigrated to Israel and became the mayor of Holon.

Rebirth of Jewish life

Following the war, Munkacs integrated Ukraine and was renamed Mukachevo. In 1966, of the 50,500 registered inhabitants, 6% declared themselves Jewish. In 2001, of the 82,200 inhabitants, they represented only 1%. Some period buildings are still standing but hardly recognizable, transformed by the Soviet era and used for other functions.

The ancient Jewish cemetery had been almost completely destroyed. Around a hundred graves were reinstalled by the community in a cemetery in the neighboring village of Koropets. a new Jewish cemetery is also present in town.

Nevertheless, in recent years a Jewish cultural life has been reborn there. A synagogue was inaugurated in 2006. All this, in large part with the help of Americans, some of whom are descendants of Mukachevo. About a hundred Jews live there today.

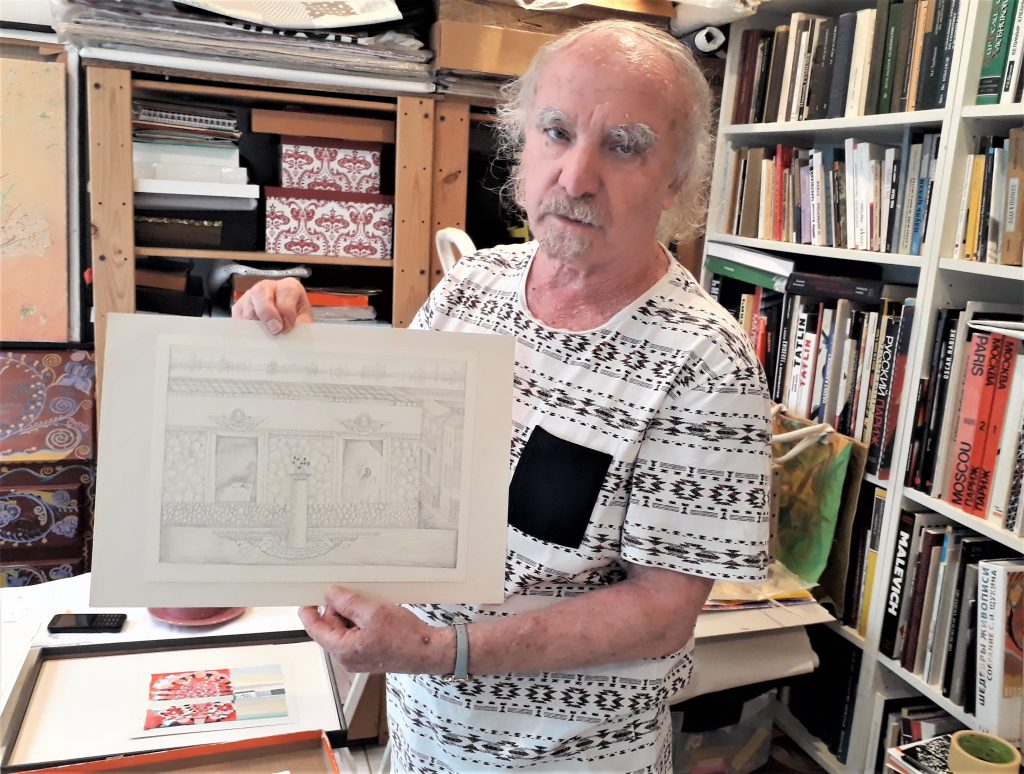

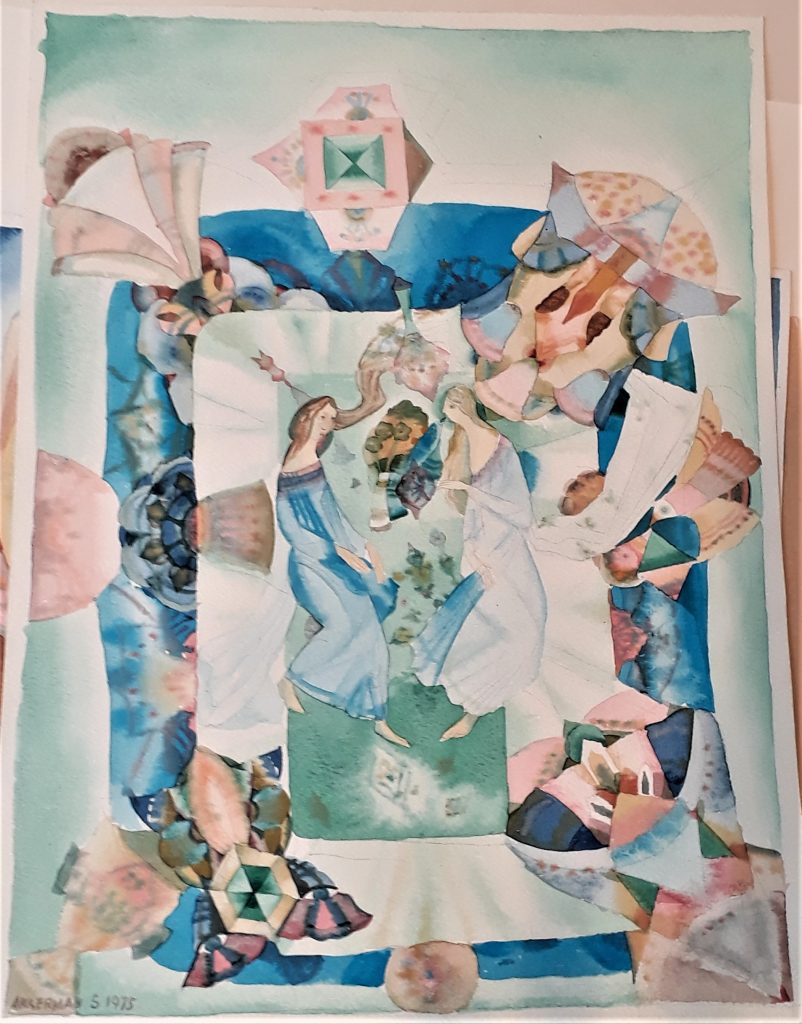

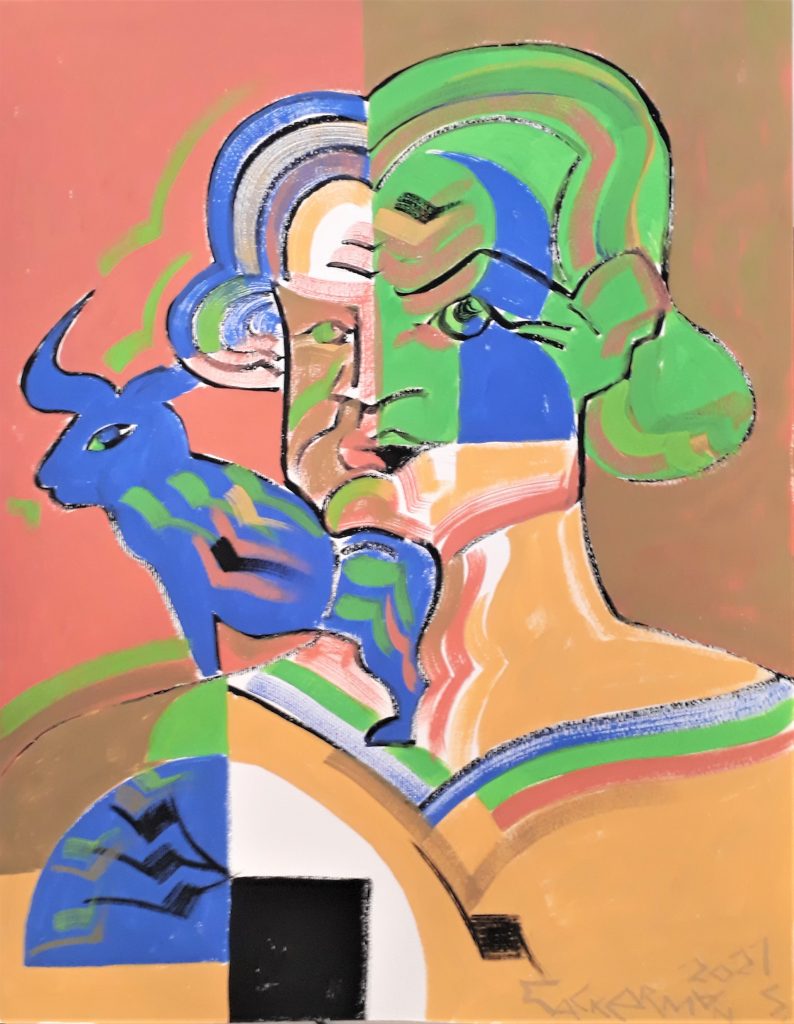

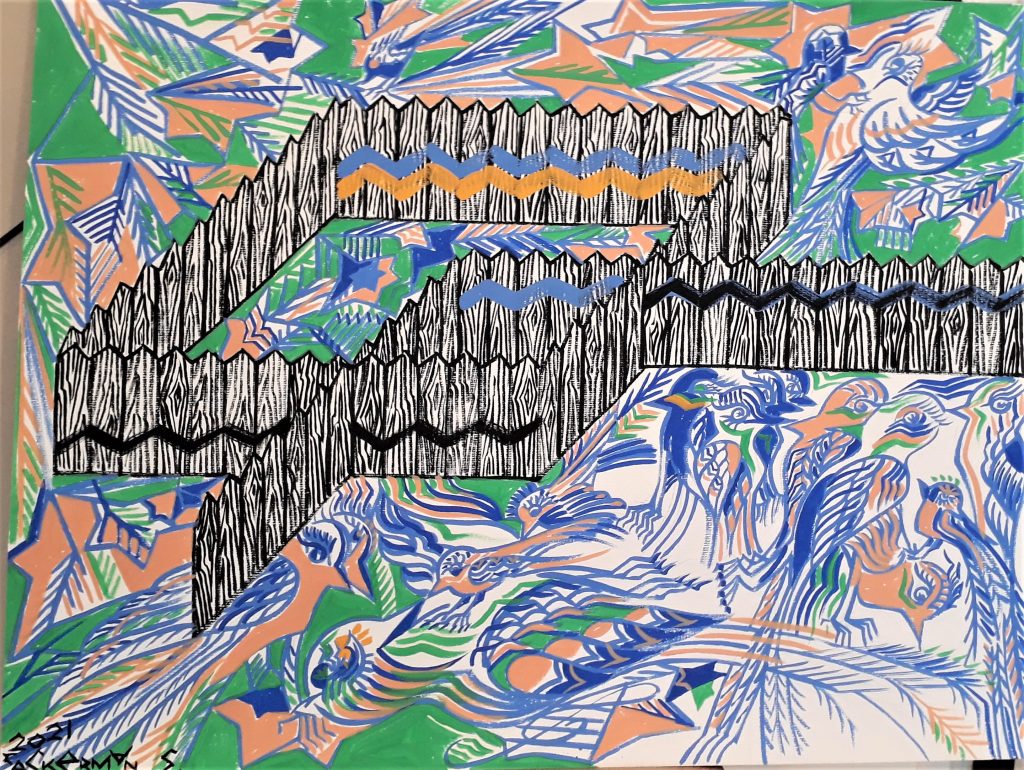

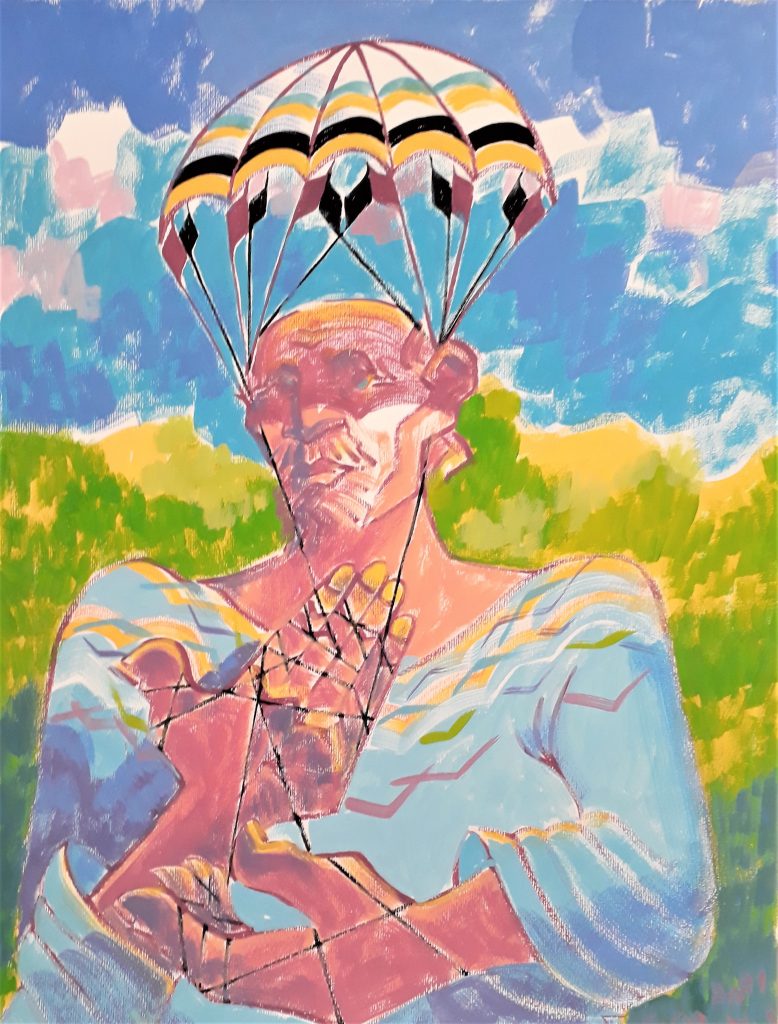

Interview of the great painter Samuel Ackerman

Born in 1951 in the Transcarpathian region, Samuel Ackerman grew up in Mukachevo and was educated at the Uzhhorod School of Art (formerly known as Ungvar when it was ruled by Hungary until the end of WWI). Places located at this cultural crossroads of languages and civilizations and at this natural crossroads made up of mountains, forests and lakes placed on top of each other like layers of paint on a canvas and where the discernment of the element which culminates can be proven difficult.

In the movie A Monkey in Winter, in his famous replica to Jean-Paul Belmondo, who enthusiastically speaks to him about the Prado, Jean Gabin prefers to see the garden that surrounds the building.

The Uzhhorod Art School and cultural and natural environments were never just surrounding each other. They influenced and responded to each other. And it is no coincidence that Samuel Ackerman, in the 1970s, became one of the most influential Israeli artists.Pursuing these dialectics between art and nature, between ancestral and contemporary culture, he unrolled his scrolls, let the imaginary creations of our inner genizah bloom in the deserts. The avant-garde Leviathan movement was born, along with Avraham Ofek and Mikhail Grobman.

In 1984, Samuel Ackerman moved with his family to Paris, where he became one of the figures of this bohemian artist from Eastern Europe, magnified from the cellars of the piano bar by Serge Gainsbourg to the ceilings by Marc Chagall.

Meeting with Samuel Ackerman to discuss the city of Mukachevo and its very special and inspiring Jewish life. The Minotaur Gallery has published a collection of much of his work.

Jguideeurope: Your family originates from the region?

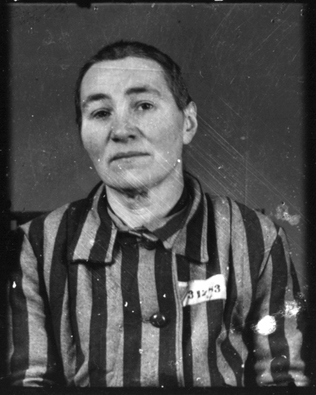

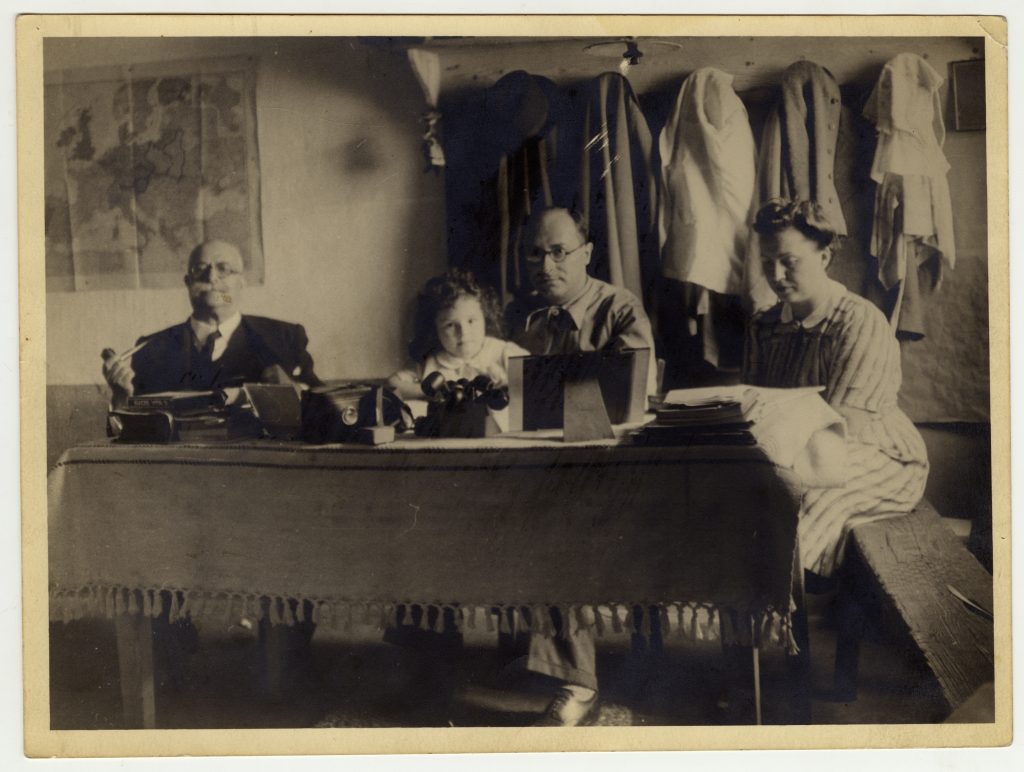

Samuel Ackerman: In Transcarpathia, there were three big cities: Mukachevo, Uzhhorod and Berehove. A large proportion of the regional population was Jewish until World War II and the mass deportation of 1944. My father, Meïr Ackerman, is from Makarovo, a village between Mukachevo and Berehove. During the war, he was sent to a labor camp. My mother, Dora Gottesman, was from Krytoye, a village north of Mukachevo. At 22, she was deported to Auschwitz. Her astonishing strength allowed her to survive. Dora’s brother also returned from a labor camp, but the rest of the family were murdered in Auschwitz. My parents met in Mukachevo after the war. They first lived in Makarovo, where I was born, and then returned to Mukachevo. Although the Jewish population of this city was almost 50% before the war, there were very few families left after the war.

I was educated in Mukachevo, before pursuing artistic studies at the School of Fine Arts in Uzhhorod. It was attached to the Academy of Prague, which allowed us to be in contact with the works of the European avant-garde, beyond the East-West divide.

What motivated you to take this path?

A drawing teacher spotted my enthusiasm and potential, giving me great encouragement. He created a small museum within the school, mixing art with botany and zoology. He taught me techniques for gouache and watercolor. His teaching, as well as the opportunity to see him at work, gave me confidence. The first time I went out to study the natural elements, I took a box of gouaches given by my father. In this season, the cherry trees were dressed in white flowers. I wanted every flower to be present in my drawing. Faced with this difficulty, I folded my sheet in half and what was painted on one side was reproduced on the other. A funny experience, but it also made me realize that art requires patience above all else. My friend Alter Vogel did the same studies four years before me. He was the one who subsequently took the photos of my artistic performances with the meguiloth in the Israeli desert. About ten Jewish artists of this time followed the same training.

What remains of Mukachevo’s Jewish life?

The sovietization of the city was rapid after the war and the buildings and street names changed, especially with regard to Jewish cultural heritage. In downtown Uzhhorod, in a small passage, was the only active but hidden synagogue for major festivals. On Shabbatot and other holidays, prayers took place mainly in the apartment of a devotee. The apartment was in Berehove Street, the one that leads to this town. My parents and other locals were generally quite religious.

Fairly practicing, which did not prevent a great openness to the world in this crossroads of languages and civilizations. Like the Hebrew Gymnasium of Mukachevo.

Unfortunately this establishment was also requisitioned after the war and transformed into barracks for the Red Army. But the menorah which appeared on the metal fence was not removed because of the solidity of this construction. This high school, along with the red brick synagogue with oriental ornaments in Uzhhorod, was funded by Czech President Tomáš Masaryk.

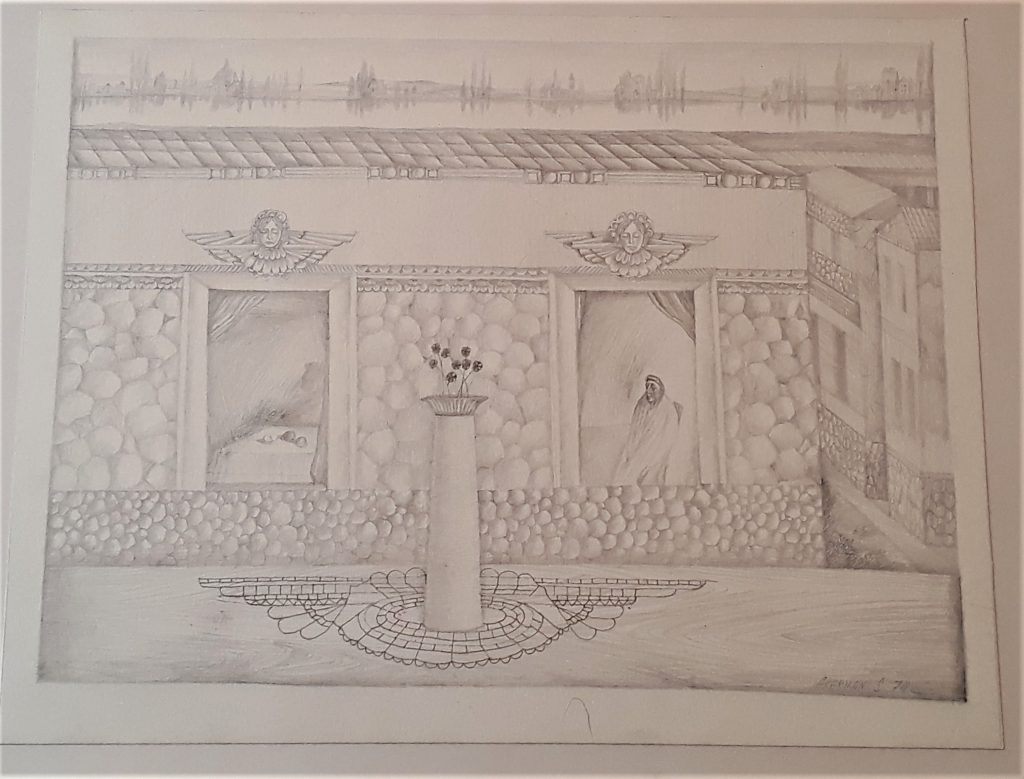

What elements of your life in Transcarpathia did you want to share in your first works?

First of all, the buildings. Similar to Brussels’ Baroque buildings with masks on the facades and other decorative elements inviting the viewer to a theater stage. I reproduced this in a drawing with a house with two windows and my father. The very pretty fortress near the city was also a source of inspiration, as were the rivers and mountains crossed by the villages of the region.

All the major cities of Transcarpathia had a fortress, built during the Austro-Hungarian Empire. In the summer, we often walked around barefoot. A direct contact with the land which I found very pleasant.

I was also marked by some amazing regional characters. Like the sculptor Turski of Mukachevo, who created the faces of wounded people in red earth, which adorned his garden. A very sensitive work that I have understood better over time.

Turski had studied in Leningrad but returned to Mukachevo before the end of his training due to health problems. In his luggage, the only book that his meager savings allowed him to buy: a collection featuring the works of Dali. Turski was the sole person in Transcarpathia to own this beautiful edition dedicated to the Spanish painter. In order to be able to consult it, those interested had to invite him to lunch. Then Turski would take them to his home to present and comment on the rare book. As a conclusion to this presentation, people were encouraged to invite him for an additional meal. But one day, falling in love with a woman, Turski entrusted the book to her to show to someone. She disappeared without leaving a trace. In the face of my friend’s distress, I coordinated an extensive regional research. This is how we found her trace in Berehove and recovered the book she used in the same way …

During your military service, you worked for the Armies Museum of the region.

Along four other people I have been tasked with renovating the museum. An interesting experience and one anecdote of which was a great source of inspiration for me concerning human comedy. A cake received by Marshal Grechko, commander of the Soviet Army who led the invasion of Czechoslovakia in 1968, was kept there in a glass mausoleum. During the renovations, two Kazakh soldiers moved the mausoleum and it shattered, along with the cake it was supposed to protect. The officers feared that we would all be sent to jail! Especially since we were expecting a visit from a very high-ranking official two days later. I told the general that I was able to repair the damage. Not by reassembling the cake, which was obviously impossible, but by reproducing it in papier mâché. I worked for 24 straight hours, reproducing the cake in great detail with all kinds of collages and colors. By also permanently closing the glass packaging that protected it, so that the high-ranking officers would not notice the subterfuge. A parable of how art can repair. It was 1971, three years after the events in Prague, a very tense period. I was also part of a group of artists creating protest works inspired by Guernica.

You left the region for Israel where you created, along with other artists from Eastern Europe, the Leviathan movement. Was it right after your military service?

Not quite. I first worked a bit for the Mukachevo theater, participating in a show. Then, we obtained the authorization to go to Israel, following an initial refusal. We created Leviathan with Avraham Ofek, born in Bulgaria, and Mikhail Grobman, from Moscow. Grobman was a little older and already benefited from some notoriety in Moscow and Israel. This land was for me like a blank canvas, with its fantasies and new forms. A very exciting experience. With total freedom for committed artists, participating at this time in tense social debates. When I discovered the work of Emmanuel Levinas, I identified with his approach. His openness to other beliefs and literature, including the work of Dostoevsky, was decisive. He, along with others such as Martin Buber, brought about a great renewal of the Jewish perspective.

Another great intellectual of this time quoted in the beautiful book dedicated to you by the Minotaure gallery is Gershom Scholem. Have you met him?

Yes, in 1979. He attended a Leviathan exhibition in Jerusalem. He very much appreciated our approach. It exhibited works inspired by Andrei Rublev, painter of Orthodox mysticism. The light crosses Jerusalem and its buildings there, a meeting between two mysticisms. Confrontations between religious and cultural worlds often transcend primary perceptions, such as the important work done by the director of the Tel Aviv museum, Mordechai Omer, who was a very religious person. In the spirit of the prophet Isaiah who brings people together in peace through encounter and creation. Each migration enriches this land. In recent decades, great Ethiopian and North African artists have given their credentials to Israeli art.

Have you been back to Mukachevo since?

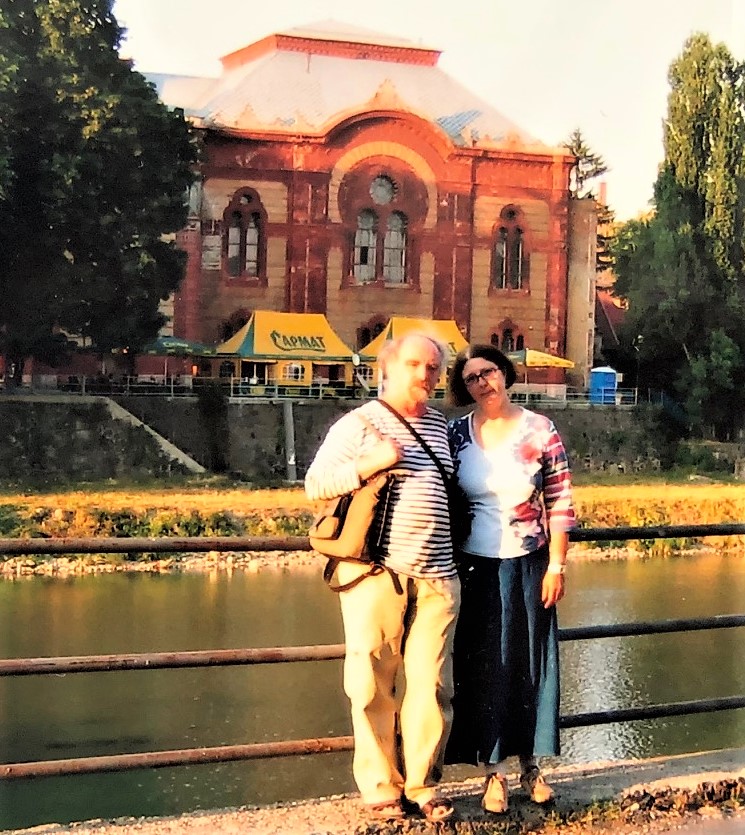

Yes in 2007, with my wife Galia. But we had visited other cities in Ukraine before such as Lvov and Czernowitz. Then, the region of Transcarpathia, before continuing our trip to Poland. It was quite moving. But I never broke the link, keeping in touch with artists from Transcarpathia here in Paris, where I have lived with my family for almost forty years.

The Jewish presence in Chinon seems to date from the 12th century. Administrative documents attest to this from the following century.

Most of the Jews lived in the rue de la Juiverie, near the Palais de Justice in Chinon. There was then a synagogue, a mikvah and a renowned study center.

On August 27, 1321, following a false accusation (frequent at the time) of poisoning wells, the 160 Jews of Chinon were burned alive in a place on the outskirts of the city, on the Island of Tours, where they were currently finds the faubourg Saint-Jacques .

Among the illustrious Jews of Chinon, we can cite the Tossafists Jacob and Nethanel of Chinon and the great rabbinical figure Isaac ben Isaac.

In response to the rise in anti-Semitic acts in France, a Garden of the Righteous was inaugurated in Chinon on 26 January 2024. It is located in the Vieux Marché, opposite the family home of Jacques Caen, part of whose family was deported and murdered in the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. The 97-year-old survivor recalled the courage of the Righteous during the Holocaust and the need to imbibe that courage today. Schoolchildren from Chinon took part in the commemoration with songs and poetry readings.

Since 11 November 2025, a street in Chinon has been named after Renée Caen, who was arrested there, deported and murdered in 1942 at the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. The inauguration took place during a ceremony attended by city officials and her youngest son, Jacques Caen, aged 98, who was taken by his mother to Joué-lès-Tours shortly before her arrest.

Source: La Nouvelle République

The Jewish presence in Bourges seems to date from the 6th century.

Following a refusal to convert to Christianity, the Jews were expelled from the city in the 7th century.

Administrative documents attest to a Jewish quarter in 1020, south of the city. It seems that a building at the corner of rue des Bourbonnoux and rue des Juifs served as a synagogue in the Middle Ages.

There would have been another synagogue in the neighborhood. As in the rest of the country, the Jews had to leave Bourges in the 14th century.

The Jewish presence in the city of Tours dates from at least the 6th century. In the Middle Ages there was a rue de la Juiverie, as well as a Jewish cemetery. However, as in all cities of France, this ancient presence came to an abrupt end with the expulsions of the late Middle Ages.

Unlike many cities, the emancipation of Jews from France following the Revolution was slow to materialize in Tours. The Jewish community did not take shape until the end of the 19th century, mainly from 1860.

Rabbis officiated in prayer rooms but the first synagogue was built in 1907 by the architect Victor Tondu thanks to a donation from the patron Daniel Iffla, Osiris said. Its stained-glass windows are signed by Lux-Fournier, glass painter in Tours. Its first rabbi, who practiced until 1937, was Léon Sommer.

In the interwar period, the Jews of Touraine saw their numbers increase, in particular thanks to the arrival of Jews from Turkey, Greece and Eastern Europe.

During the Second World War, the Jews of Touraine were arrested and interned in the camp of La Lande in Monts.

While a party managed to join the bush or go into hiding, three quarters of the members of the community were deported and died during the Shoah. The survivors set out to rebuild the sacked synagogue and Jewish life in the city of Tours.

On April 19, 2005, Simone Veil inaugurated the stele in homage to the 34 Righteous of Indre-et-Loire (42 today), which is in the courtyard of the synagogue.

Among these Righteous, Léa Keresit, nurse at Saint-Gratien Hospital, who actively participated in a group of smugglers who saved many Jews.

The 1960s saw the arrival of Jews from North Africa, forming the majority of people of the Jewish faith today.

Created in 2009, the Israelite Cultural Association of Indre et Loire participated with the local authorities in the organization the following year of numerous events marking the 150th anniversary of the community.

In 2019, a ceremony was held Tours’ City Hall to pay tribute to the 1,019 Jews deported between 1942 and 1944, of whom only 38 returned.

The work of the Association for Research and Historical Studies on the Shoah in the Loire Valley (Areshval) made it possible to find these names.

Unlike the majority of other cities in the region, the Jewish presence is attested in Orléans from the 6th century.

In 585, the Orléans Jews participated in the welcoming ceremony in homage to King Gontran. It seems that they asked him for the possibility of building a new synagogue following the destruction of the previous one. The Jewish community of Orleans was quite large in number in the Middle Ages.

Orléans became in the 12th century an important center of Jewish studies with personalities such as Isaac ben Menahem, Abraham ben Joseph, Eleazar ben Meir, Yaakov of Orleans and especially Joseph ben Isaac Bekhor-Shor.

The Jews were expelled from Orléans in 1182 and the synagogue turned into a chapel. They were able to relocate there, but under many conditions and impositions. There was in the following century a district of the Jewry and two synagogues in the city. But at the end of the 14th this relocation ended with the expulsion of the Jews from France.

Following the wind of emancipation from the French Revolution, a small community was reconstituted in Orléans in the 19th century with around 40 members having a synagogue.

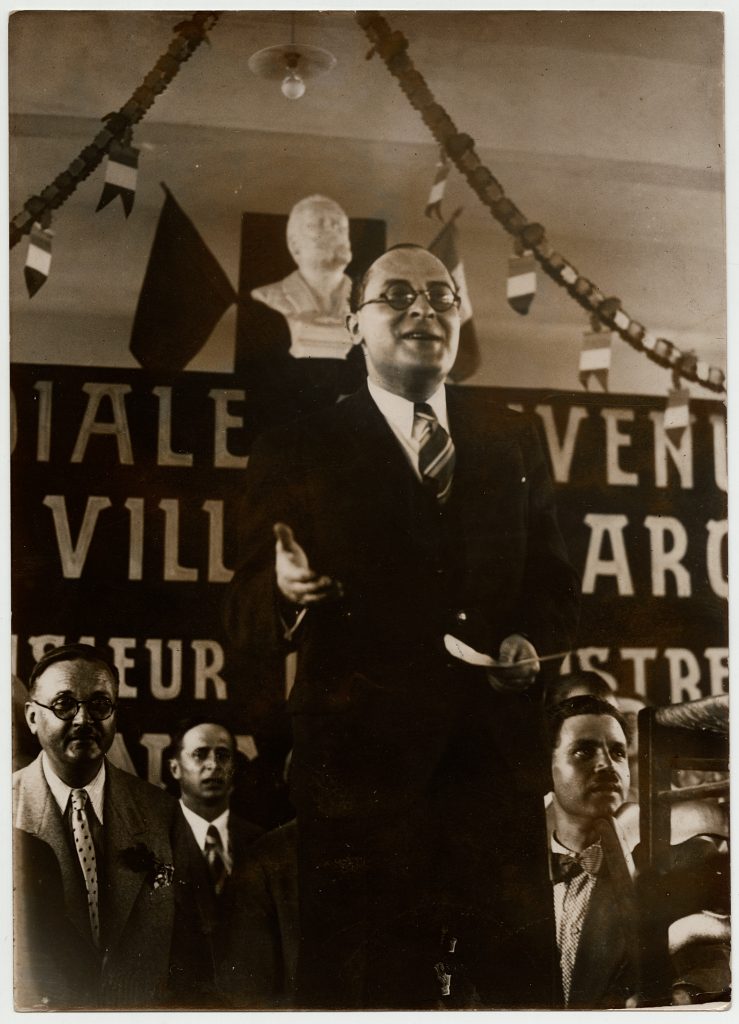

On a plaque commemorating the soldiers who died for France during the First World War is the name of Léon Zay. Director of the regional newspaper “Le Progrès” du Loiret, he was also the father of Jean Zay. The latter was born and raised in Orléans. Member of Parliament for Loiret, he became Minister of Education and Fine Arts in the Popular Front government from 1936 to 1939. He was behind many school reforms and the Cannes Film Festival. He left the government in 1939 to join the army and go to the front. He was arrested by Vichy troops and imprisoned in 1940. He was assassinated by militiamen in 1944.

The Nation paid a tribute to Jean Zay after the war. When he entered the Panthéon in 2015 (with the other Resistance fighters Germaine Tillion, Geneviève de Gaulle-Anthonioz, Pierre Brossolette), the city organized a series of events to mark the transfer of the coffin. A high school in Orléans bears his name. A strong tribute to Professor Samuel Paty took place there following his assassination in 2020.

In May 1969, Orléans Jews, who numbered around 500 people, fell victim to a conspiratorial rumor, creating a climate of tension in the city. The efforts of local authorities, intellectuals and the press deconstructed this rumor.

In 2025, the city has 400 Orléans Jews and a synagogue since 1970, located in a former oratory provided by the city and the bishopric.

On 22 March 2025, Rabbi Arié Engelberg of Orléans was violently attacked in the street, reinforcing the vigilance of the Jewish community in Orléans and its determination to stand up to hatred and violence, as the rabbi did that day.

Interview of Olivier Loubes, historian, member of the STUDIUM research group (University of Toulouse) and author of the book Jean Zay. The Unknown of the Republic (Colin, 2012), an expanded reissue was published, under the title Jean Zay. The Republic in the Pantheon (Dunod: Ekho, 2021).

Jguideeurope: How did you become interested in the work of Jean Zay?

Olivier Loubes: By chance and out of necessity. Chance was my appointment as a high school professor in Orléans in 1989. Necessity was my research work for a DEA, then a Thesis, which focused on the relationship between school and nation in the first half of the 20th century.

One day in the Les Temps Modernes bookstore in Orléans I was leafing through Jean Zay’s remarkable book Souvenirs et solitude which had just been reissued and the bookseller asked me what I thought of it. I share with her my admiration for this book and its author. With that, she confesses to me that it is about her father. This meeting with Catherine Martin-Zay changed my life as a historian. Catherine and her sister Hélène Mouchard-Zay, gave me access to Jean Zay’s personal archives, before they were given to the National Archives in 2010. Since then, I have written two books on Jean Zay, one on the creation of the Cannes Film Festival under his leadership, as well as some twenty articles to better publicize his work and his time.

What were the great moments of his life that linked him to Orléans?

As he said himself, Jean Zay knew every stone in Orleans. He was born there, spent his childhood there, studied from elementary school to high school. He worked there, in his father’s diary, then as a lawyer. His political life began as a deputy for Orleans in 1932. All his life (except his law studies in Paris) until his arrest in 1940 was linked to this city.

The republican commitments of Jean Zay motivated you in particular in the writing of this book. Are these beliefs inherited from his family?

Jean Zay was born into a family of people “mad about the Republic” as Pierre Birnbaum calls them. With a Jewish father and a Protestant mother, these religious minorities who fought fiercely for this Republic which granted them equal rights. The family of his mother, Alice Chartrain, defended the cause of Captain Dreyfus. Originally from Alsace, his paternal family opted for French nationality in 1870, already showing a strong attachment. Léon Zay is a radical-socialist republican close to the Socialists, an employee of the Dreyfus newspaper Le Progrès du Loiret, of which he will become the Editor-in-Chief. Jean Zay grew up in this highly politicized family within the Republican left and got involved early, helping to found the “Republican Secular Youth” in Orleans. An approach anticipating the Popular Front, by bringing together young people from different left-wing parties. The bond with his parents remains very strong. When Jean Zay is imprisoned, his father (his mother was then deceased), his wife and his two children stayed in a hotel next to the prison to stay near him.

His Republican commitments are sometimes difficult to understand nowadays and not highlighted enough, motivating the writing of this book which was published in 2012 and is now available in pocket edition with additions, in particular on the pantheonization and the attacks that his person and his memory are still suffering. So many personalities claim his heritage, although sometimes very far from his vision, it was therefore interesting to present his commitment to the Republic. A parliamentary-type Republic that he imagined as a social democracy guaranteeing the right to education, housing, health, retirement …

How are these commitments important in our contemporary debates?

First, because these values of parliamentary republic and social democracy can inspire in depth many contemporary reflections on change in the Fifth Republic. It should be added that it is important to note that Jean Zay’s engagement also took place at a particular time. The anti-fascist dimension of his fight is not negligible, both in France and abroad. Jean Zay’s creation of the Cannes Film Festival is a direct response to Mussolini and Goebbels’ stranglehold on the Venice Film Festival. He is at the origin of cultural diplomacy, believing that liberal democracies must show their strength in this way.

Two fights led by Jean Zay are particularly echoed today. First, that the education be of the best possible quality and shared by all. Then, that the democratization of culture allows a strong political democracy. Combining action with rhetoric, he fought for better budgets and better use of education and culture.

Are his school reforms at the center of his fight?

Not when he began his political career in 1932, for he was then a generalist in politics. All predicted him a meteoric rise to the highest steps, being appointed minister at 31 years old. Nevertheless, in his concern for building social democracy, these fights for the school are at the heart of his project, since he was appointed Minister of National Education and Fine Arts in 1936. Si Jules Ferry wanted to make school accessible to all in order to train citizens, Jean Zay adds to it the desire that pupils and students from different social backgrounds continue their studies as far as possible so that they guarantee the functioning of democracy social.

The Jewish presence in Chartres seems to date from the 12th century, documents attest to it for 1130.

Places still mark this presence, such as the rue aux Juifs . The old synagogue would have been located where the Saint-Hilaire hospital is now.

At the end of the 19th century, dwellings in the streets of the Jews will be sources of inspiration for the novel La Terre by Emile Zola.

Among the illustrious Jews of Chartres, note the presence of Mattathias, a contemporary of Rashi, but also Joseph of Chartres, author of biblical commentaries, and the poet Samuel ben Reuben of Chartres.

On 27 January 2025, a ceremony was held in Chartres to commemorate the 80th anniversary of the liberation of the Auschwitz-Birkenau camp. Chaired by the Eure-et-Loir Prefect, Hervé Jonathan, the ceremony took place in front of the stele honouring Jewish deportees from the Eure-et-Loir. The ceremony was attended by elected representatives, representatives of the civil and military authorities and, above all, secondary school pupils. The prefect reminded them of the dangers of the rise in anti-Semitic acts and the authorities’ determination to stand firm.

The Jewish presence in Blois seems to date from the end of the 10th century.

But the city was infamous for the first anti-Semitic charge of ritual murder in 1171. About 40 Jews lived there then. Isaac Ben Eleazar was accused of having thrown a child in the Loire. 33 Jews were imprisoned and murdered following this false accusation based on unfounded rumors and the transmission of anti-Semitic theories of the time. This tragedy was commemorated by the Jews of nearby Orleans. Rabbenou Tam declared the day of the assassination a youthful day for the European communities.

Few Jews settled there again before the French Revolution. We note, however, the existence in the 14th century of a “district of Jewishness”. Where the rue des Juifs is today.

At the start of the 20th century, a few Jews from the eastern regions came to Blois, forming a small community with Jews from North Africa who settled there in the 1960s.

During the Second World War, Blois was the scene of numerous fights to liberate the city. A Resistance, Deportation and Memory Center was opened there in 2019. Pierre Sudreau, the former mayor of the city from 1971 to 1989, was a very committed Resistance member. This center replaces the old Resistance Museum. Smaller but more central, it facilitates access for school groups and tourists.

Today, around 20 Jews live in Blois, who meet in a prayer room for major festivals. In 2020, the faithful of Blois created their own association, officially recognised by the Central Consistory as a Jewish community, marking a renewal.

A memorial plaque was unveiled on 11 May 2025 on Rue des Juifs in Blois, commemorating the first accusation of ritual murder levelled against Jews, which took place in Blois in 1171. Thirty-two Jews were massacred in Blois at that time.

The long-standing presence of Rue des Juifs attests to an equally long-standing Jewish presence. By commemorating one of the first pogroms against Jews in Europe, political leaders, including the mayor and the prefect, and religious leaders are expressing their desire to unite in promoting peace, particularly at a time when anti-Semitic acts are so prevalent.

Source: France 3 Régions

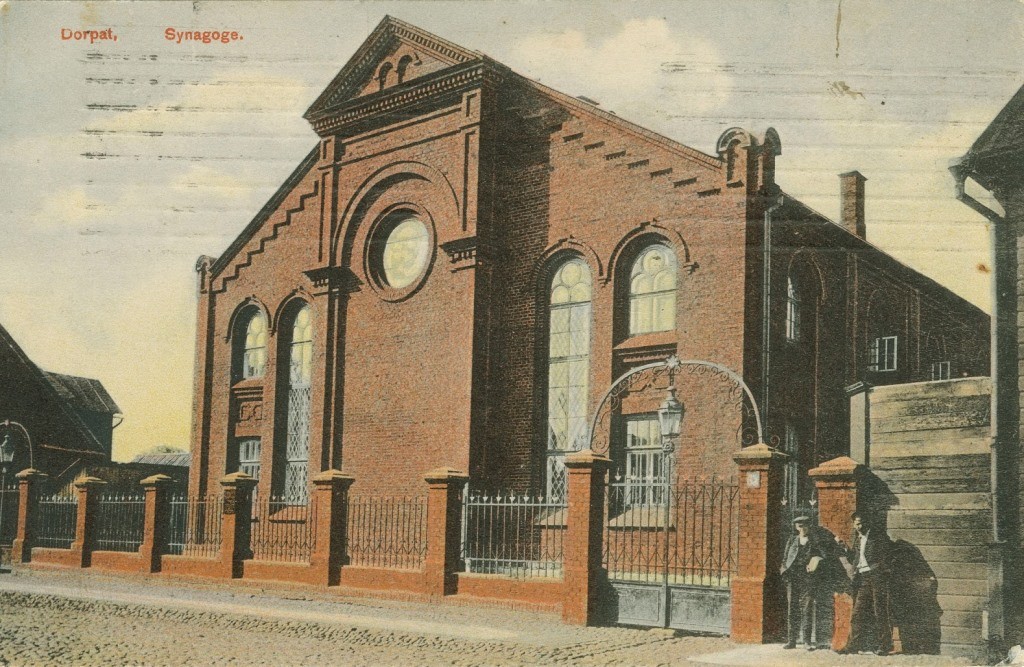

Like the city of Tallinn, the Jewish community of Tartu was founded mainly by retired Russian soldiers, previously stationed in the city. Thus, the former soldiers of Nicholas built a synagogue in 1876 in the city of Tartu.

By the turn of the 20th century, there were nearly 1,800 Jews in the city and thriving educational institutions. Among them is the Association for the Study of Jewish History and Literature. Among its members is Jacob Bernstein Kogan.

However, this figure declined and they were only 920 in 1934. One consequence of the Russification of the University of Tartu, which imposed a quota, reducing the number of eligible Jewish students.

A Jewish Studies Seminar was opened at the university in 1934, under the direction of L. Gulkowitsch, then M.J. Nadel and H.J. Welcoming Port. This intense intellectual life was interrupted by the Soviet invasion and then the German occupation. The Shoah claimed many lives in the city. The synagogue was destroyed during the war. The Estonian National Museum now preserves artifacts that were present there.

In the aftermath of the war, 200 Jews returned to the city, later joined by Jews from other parts of the USSR. However, many of them emigrated to Israel around the turn of the Six-Day War.

At the end of the 18th century, with the emancipation of the Jews in the country, the city of Norrköping, like Goteborg and Stockholm, hosted its first synagogue, built by Jacob Marcus. Another place previously hosted Jewish ceremonies.

The current synagogue was built in the mid-19th century by architects Edvard Meden and Carl Stal. Due to the decline of the city’s Jewish population, the synagogue rarely hosts events, mainly major festivals.

Anti-Semitic acts do not spare small towns like Norrkoping. In 2018, a bag with a Star of David containing anti-Semitic leaflets and soap was placed in front of a venue hosting a Holocaust exhibition.

The Jewish presence in Sarreguemines seems to date from the 13th century. However, the sustainability of this installation will only take place with the wind of emancipation of the French Revolution.

A rabbinical seat was created in the city in 1791. There were 350 Jews from Sarreguemines in 1861. That year, a Byzantine-style synagogue was built on rue de la Chapelle. The Jewish population increased following the arrival of German refugees after the war of 1870 and that of Polish refugees in the interwar period. A Jewish cemetery was established in 1899.

The Shoah caused many victims in the region, especially in Sarreguemines. 95 Jews from Sarreguemines were deported out of the 395 present in the city. And five fall with arms in hand to defend France. The synagogue was destroyed in 1940 by the Germans, and the cemetery was very degraded.

Sixty-six Jewish families are still present at the Liberation. The contemporary-style synagogue was rebuilt in 1958. A moving inauguration ceremony took place in March 1959, in the presence of local authorities. Visits to the synagogue and other places where traces of this long Jewish presence can be found in the city are organized regularly, especially during Heritage Days.

In March 2024, the Jewish community of Sarreguemines celebrated the 65th anniversary of the synagogue. The synagogue was built in 1959, the former synagogue having been blown up in 1940.

During the 2025 European Days of Jewish Culture, the town of Sarreguemines offered a wide range of activities. These included a tour of the town tracing Jewish culture, a visit to the Jewish cemetery in Frauenberg, and a lecture entitled ‘Kaddish for a teacher’ with Laurence Jost-Lienhard recounting the story of teacher Maurice Bloch, who was deported to Auschwitz on 20 November 1943, and the fate of his pupils. A klezmer concert by the group Di Freynt was also given as part of the Cultural Season.

Sources : Le Républicain lorrain

Forbidden to stay following pressure from local merchants, the first Jews to settle in Sarrebourg did so after the French Revolution and national emancipation. The first birth of a Jew in Sarrebourg therefore dates from 1794.

The community acquired land that could be used as a cemetery in 1812. An oratory was installed a few years later on the first floor of a house. A synagogue was officially opened in 1857 on rue du Sauvage on land acquired twelve years earlier, in particular thanks to the activity of Léon Lippmann, an emblematic figure of the Saarebourg Jews.

In 1889, the Jews constituted nearly 10% of the population of Sarrebourg. Jules Lévy became mayor in 1877.

Seventy-five people will be deported and murdered during the Shoah. As in other cities in the region, the US military chaplaincy is helping to rehabilitate the synagogue after the Liberation.

The decline of the Saarebourg Jewish population has resulted in recent years keeping the synagogue open by a few worshipers without an official rabbi. It is one of the last in the region still in operation. The Heritage Days allow each year to highlight its historical importance.

In 2022-3, pupils in the third year of secondary school at Sainte-Marie took part in a remembrance project. The project focused on the tragic experiences of Jewish children in Lorraine during the war years.

Sources : Le Républicain lorrain

The Jewish presence in Epinal seems to date from the 18th century, following the arrival of merchants from Alsace. But only one Jew was recorded in the city in 1771. The wind of emancipation of the French Revolution allowed Jews to settle in the city in a more lasting way. Thus, the number of Spinalian Jews increased from 19 in 1806, 350 in 1856, 380 in 1900 to 450 at the dawn of the First World War.

In the interwar period, the Spinalian Jewish population declined to 370 but was reinforced by the presence of Alsatian Jews. The synagogue was built in 1863, but the community had its first rabbi in 1835. Among the officiating rabbis is Moses Durkheim, the father of Emile, the founder of sociology. The synagogue was destroyed during the Shoah.

The Jewish cemetery dates from 1842 and is located on rue Saint-Michel. A memorial in memory of the Vosges Jewish martyrs of the Shoah was erected there. 90 Spinalian Jews are murdered during the Shoah.

Léon Schwab , decorated soldier during the First World War, lawyer and mayor of Epinal before the war who was forced to resign during the occupation, returned to his post at the Liberation. He was very active in the cultural promotion of the region, especially after his mandate as mayor.

A new synagogue was built in the 1950s. The Jewish population is declining, and today only represents about 30 families. But with the help of foundations, the synagogue is being renovated and saved from closure in 2018.

Ten cobblestones paying tribute to Jewish deportees were laid in Épinal in September 2025, in collaboration with the Stolpersteine association. This necessary initiative was led by local historian Alexandre Laumond. In memory of nine victims of the Holocaust: Szlama Rozenberg, Paul Glicenstein and his wife Cyrla Baron, Yvonne Judas – wife of Lucien Halbronn -, Ida Willard – wife of Georges Halbronn -, Margot Wolff – wife of Marcel Halbronn -, Hinda Rotenberg – wife of Rapoport -, and her children Sara Rapoport and Iser Israël Rapoport. Also Marie Antoinette Gout, a member of the Resistance who was deported and recognised as Righteous Among the Nations for helping to save Josette and Norah Hecker, Régine and Simone Banda, and Jean-Michel Weill.

An audio tour recounting the history of the Holocaust was designed in collaboration with students and history teachers from the Lapicque and Claude-Gellée secondary schools in Épinal.

Source: Vosges Matin

The Jewish presence in the city and in the area probably dates from the 9th century. But it persisted much later, in a more structured way, in the 16th century. The following century, we find traces of Jewish families from Metzervisse.

Small synagogues are springing up in the region, but in Metzervisse, as elsewhere, they are generally located behind buildings by local pressure to keep quiet.

The Metzervisse synagogue was built in the middle of the 18th century. Destroyed, walls have survived on which we can distinguish religious elements, in particular the Holy Arch and the mikve.

Metzervisse’s Jewish cemetery is located at the entrance to the village. Numerous tombs, especially of certain large families, attest to the part played in the history of the city by the Jewish population during the different eras.

The French Revolution enabled the emancipation and growth of the Jewish population of Metzervisse, as it did at the same time in the rest of the region and of the country.

If it constituted for a time 17% of the general population, the number is declining rapidly. A trend it also followed in the 20th century.

In 2024, six memorial paving stones were laid in tribute to the victims of the Shoah, to honour the members of the Picard family who were deported and exterminated at Auschwitz. The Mayor of Metzernisse, Pierre Heine, stressed the importance of this act to remember the former Jewish presence and the need in our difficult times to pay tribute to the victims of the Shoah.

Sources : Moselle tv

The Jewish presence in Forbach seems to date from the 17th century. Very few people were affected until the middle of the 18th century. An oratory was installed in 1733 and a small Jewish quarter began to form on rue Fabert.

If on the eve of the French Revolution a complaint was lodged about the quota of Jews exceeding the authorized number, the wind of emancipation had rapid effects in the region and more particularly in Forbach. Thus, Lion Cahen became, in 1799, the first Jew to lead a medium-sized town in Lorraine, appointed municipal agent acting as mayor. A provisional but revolutionary appointment.

Despite certain tensions, the Jewish population of Forbach increased in the 19th century, with 314 Jews constituting just over 10% of the population.

Much work was necessary during the 19th century to renovate the synagogue , built in 1836 on land purchased seven years earlier. They took a long time and were completed in 1929. A sign of their successful integration into the city, several Jews were mayors of Forbach at the start of the 20th century: Marx Haas, Félix Barth and Ernest Klauber.

The Shoah had devastating effects on the Jews of Forbach. 115 will be deported, among them Hazan Henri Kaufmann , holder of the 1914-18 War Cross. In memory of his memory, the city gave him a street name. Residents of Forbach and the region made courageous decisions, saving Jews. Among them, the niece of the bishop of Metz, Monsignor Heintz, who hid the family of Benjamin Cahen who became president of the community from 1959 to 1980.

At the Liberation, the synagogue, which had been used as a depot of goods by the occupants, was restored.

Hundreds of Forbach Jewish families lived in the city in 1980. However, these figures have declined drastically in recent years. The synagogue was consequently decommissioned by the consistory and taken over by the city in 2015 and transformed into a place of culture.

In March 2025, a tree was planted in the grounds of the residence of the sub-prefect of Forbach in tribute to Livie Brunwasser, 97, a Holocaust survivor. This magnolia tree was planted in the company of students from Blaise Pascal High School. Livie Brunwasser shared her memories of her childhood in Forbach and of the Second World War with the students. Six of the seven members of the Laufbaum family were deported to the Auschwitz concentration camp. She was able to take refuge in Charente, the sole survivor of her family. During the ceremony, she said: “But I was lucky to have a loving family and to marry a hero. I was also very fortunate to live in France, which has done so much for its martyred and humiliated people. As long as I have my eyes open, I will be grateful.” ” A plaque was also installed in the garden of the residence of sub-prefect Franck Chaulet. Students at Blaise-Pascal High School created a memorial suitcase to pay tribute to the deported Jews.

Source: Le Républicain Lorrain

The Jewish presence in Saint-Avold has been documented since the 15th century. A prior presence in not documented. A very small number of Jews were allowed to remain in the city in the 17th century, which didn’t prevent them from being victims during that century of several waves of expulsion.

The wind of emancipation of the French Revolution allowed Jews to settle more permanently in the city. The first synagogue was installed in an apartment in 1808. The building accidentally burned down and the synagogue was relocated to a building on rue des Anges.

About 50 Jews lived in Saint-Avold at this time. This number will rise to 134 in 1845. Following the arrival of German Jews after the War of 1870, the number of Naborian Jews rose to 159 in 1900. The city’s Jewish cemetery dates from 1902. It is located a little outside of the city, in Hellering.

Among the city’s Jewish personalities, industrialist Aaron Hertz, builder of a horn factory and mayor, and especially Herta Strauch, author of the novel Catherine Soldier.

Of the hundred or so Jews present before the war, forty-four were murdered in deportation. The synagogue was destroyed in 1940 by the Nazi occupiers. A synagogue was built in 1960 by architect Roger Zonca in a contemporary cubic style.

The American Military Cemetery is the country’s largest necropolis in Europe. Of the 10,000 graves, 400 are those of American Jewish soldiers who fell with weapons in hand to liberate Europe.

About sixty Naborian Jews now live in Saint-Avold.

In June 2024, the Jewish community unveiled a commemorative plaque at the Saint-Avold Jewish cemetery in memory of the Nabor victims of the Shoah. Throughout the year, 28 final-year students from Lycée Poncelet took part in an educational project with the Shoah Memorial to retrace the lives and honour the memory of the Nabor victims of the Shoah.

Sources : Le Républicain lorrain

The Jewish presence in Thionville probably dates from the 14th century. There seems to have been a Jewish cemetery in the following century. Very few families were granted the right to settle in the city before the end of the 18th century, deserting the surrounding small rural communities. 14 Jewish families lived in Thionville in 1795.

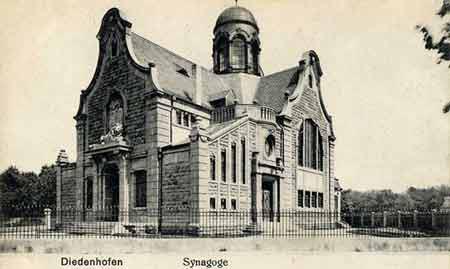

A synagogue was built in 1805, rue de la Poterne. A three-storey house that will be refurbished, in use until 1912. That year it was replaced by the synagogue located on Boulevard Clemenceau.

40 Jewish families from Thionville lived there in 1812 and 332 in 1910, a figure increased by the arrival of German Jews. The number declined in the interwar period to reach 281 families in 1931.

During the Holocaust, five Jews were shot by the Nazis and 30 families deported. Also, the Jewish cemetery was ransacked and the synagogue destroyed by the occupier during the war.

It was rebuilt in 1957 in a modern style with a dome topped with a Star of David. It is located on rue Henri Lévy, a name given in homage to the rabbi deported and assassinated at Auschwitz in 1944.

The Jewish community was reconstituted with the help of chaplains from the American army. A community center was opened in 1966, and Thionville Judaism remains very active.

Jews from Germany settled in Boulay at the beginning of the 17th century. It is in this city that Raphaël Lévy lived, falsely accused and executed in 1670 for “ritual crime”.

Duke Leopold confirmed the authorization of the settlement of 19 Jewish Boulageois families, which had a synagogue, built in 1670, a Jewish school and a cemetery . But their discretion is imposed and taxes put in place. A large part of Boulay Jews were expelled in 1721.

Following the emancipation, fruit of the Revolution of 1789, the population increased in the 19th century. Thus, there were 137 Jews in 1808 and 265 twenty years later. A new synagogue was built in 1857. His hazan in the 1930s was Charles Lichtenstein.

Of the hundred Jews present in the city on the eve of the Second World War, 11 were deported during the Shoah.

The synagogue was destroyed by the Nazis and rebuilt in 1955. A plaque is affixed there in memory of the dead of the two wars.

A prominent figure in the Jewish community, Léon Paul Lazard, whose company produced the famous Boulay macaroons from 1854.

About thirty Boulay Jews resided in the city in 1968. Only a few families live there today. The synagogue was closed in 2023.