The Jewish presence is mentioned in Morhange at the end of the 17th century, apparently with the installation of the first Jewish family.

In 1686, a complaint was filed by the inhabitants of the city against the presence of Jews, limiting their installation. They were forced to live mainly on a separate street. Most gradually left the city to settle in Metz.

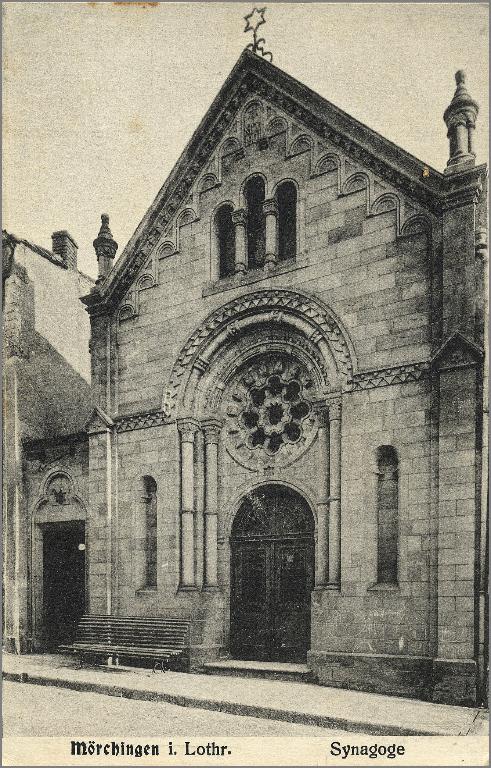

The French Revolution and the emancipation of the Jews that followed allowed a resettlement in Morhange. A synagogue was built at the beginning of the 19th century. A rabbinate was set up in the city in 1910.

Forty-five Jews resided in Morhange in 1939. Six died in deportation during the Shoah and the synagogue was destroyed.

A plaque recalls the presence of the synagogue, whose facade is known mainly from old postcards celebrating it. But it was not rebuilt after the war, Morhange having very few Jews. The city also has a Jewish cemetery .

The Jewish presence in Lunéville is mentioned at the end of the 15th century, shortly before the expulsion from Lorraine.

Only two families were allowed to settle in the city at the beginning of the 18th century. And only sixteen lived there in 1785 when the synagogue was built by the architect Charles Augustin Piroux, the first to be built in the kingdom of France since the 13th century.

An exceptional authorization granted by Louis XVI, hence the presence of royal symbols on its facade. Six years later, a Jewish cemetery is granted.

Following the momentum throughout French territory following the Revolution of 1789, the Jewish population obtained the rights of citizens in Lunéville.

315 Jews lived in this town of Meurthe-et-Moselle in 1808 and 400 in 1855. Equal rights also favor intellectual and cultural development. In particular by the publication of Hebrew texts. The war of 1870 caused the flight of Jewish refugees who settled in the region.

Eighteen Lunévillois Jews fell with their arms in their hands during the First World War and six during the Second. Of the 194 Jews deported during the Shoah, only 9 survived.

In 1969, the city had around 200 Lunévillois Jews, a large part of whom came from North Africa.

There is also in Emberménil, near Lunéville, a Museum in homage to Abbé Grégoire , parish priest of Emberménil, who fought fiercely for the emancipation of the Jews of France during the Revolution.

In 2024, eight memorial paving stones were laid in Lunéville, on rue des Bosquets and rue du Château, to honour and preserve the memory of local families who were victims of the Shoah. The Hubermann and Lang families in particular.

Sources : L’Est républicain

The presence of Jews in Verdun was fleeting in the Middle Ages, often banned from settling there. Despite this, some Tossafist scholars of Verdun are references like Samuel Ben Hayim and Samuel Ben Yosef.

Even in the 18th century attempts to settle Jews in the city for a long time met with little success and led to expulsions.

The Jewish community was perpetuated at the time of the French Revolution and was attached to the consistory of Nancy. It had 217 members in 1806.

The city of Verdun has a synagogue and a Jewish cemetery . A first synagogue was built in 1805 but was destroyed during the War of 1870. The current synagogue , classified as a historical monument, was built in the years following the conflict in a Hispano-Moorish style.

Only a dozen Jewish families still live in Verdun, and the synagogue is mainly open during major holidays only, for lack of minyan. The synagogue was renovated in 2022.

In April 2024, as part of the events commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Liberation of Verdun, 18 memorial stones were laid. They bear the names of deported Jewish families who lived in Verdun, including the Isler, Faindt, Mayer-Tabaksmann Laktichoff, Wildmann and Rosa Kawa families. This commemoration was made possible by the work of historians Jean-Pierre Harbulot and Gérard Domange.

Ten new Stolpersteine were laid on the pavements of Verdun in August 2025 in memory of the Laktichoff, Wildmann, Isler, Fraindt and Tabaksmann families. In this way, the city paid tribute to ten Jewish residents of Verdun who were arrested during the Second World War, deported and murdered. This project was led by the municipality with the aim of perpetuating the memory of these residents.

Sources : L’Est républicain

Metz is surprising for many reasons. Firstly, the richness of its medieval architecture and that of subsequent centuries, influenced by numerous conquests and reconquests. With its palaces, symbols of authority, protective fortifications and bridges to other shores and cultures that blend harmoniously. Metz is anything but a city with a museum-like central district. It’s a city whose cultural continuity has been preserved and stimulated, to the delight of tourists and the pride of the locals.

A city famous for its splendid cathedral, its lively Place de la Comédie and Place Saint-Jacques, the homes of François Rabelais, Paul Verlaine and André Schwarz-Bart and its many houses built with Jaumont stone. And of course its prestigious museums, including the Musée de la Cour d’Or tracing the history of the city and the Centre Pompidou-Metz, tracing the artistic link between past, present and future, as it did in 2019-2020 with its splendid exhibition dedicated to Sergei Eisentein.

The Jewish presence in Lorraine appears to date back to ancient times. However, it is only documented in Metz in 599 in correspondence between the Pope and the kings of Austrasia. The main sites devoted to Metz’s Jewish cultural heritage are located in a relatively small area, between the synagogue and En Jurue , rue du ghetto, where there was probably a very old synagogue, where the ghetto gate can still be seen and where André Schwarz-Bart lived. Nearby, in the Cloître des Récollets, are the municipal archives of Metz, very useful for researchers.

Another must-see place for learning about the history of Metz is the Cour d’Or Museum , at the intersection of the triangle formed by the cathedral, the cloister and the synagogue. Its many rooms allow visitors to discover 2,000 years of Metz history, thanks in particular to Gallo-Roman statues and mosaics, medieval finery and weapons, and modern paintings by the School of Metz.

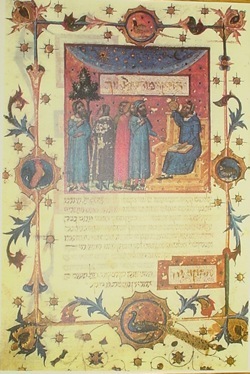

There is also a room dedicated to the Jewish cultural heritage of Metz. The ‘Perennial Memory’ project was launched at the museum in 2023, with the aim of renewing the museography of the history of this community. The project was launched in partnership with the European Days of Jewish Culture, under the impetus of its regional president, Désirée Mayer, and with the participation of artist Jean-Christophe Roelens. The harmonious presentation combines works of art, antique objects, interactive technological content, photos and explanatory texts, enabling visitors to appreciate the diversity and age of Metz’s Jewish cultural heritage.

History of the Jews of Metz

The first official document attesting to the presence of Jews in Metz was a provincial council in the Middle Ages, which prohibited Christians from dining with Jews. However, many Christians did not follow this advice and friendly and intellectual exchanges continued around these tables. Sigebert of Gembloux (1030-1112), for example, consulted Jewish scholars to translate passages from the Bible. This was a time when the region stretching from Champagne to the Rhineland communities of Speyer, Worms and Mainz, via Alsace and Moselle, was home to an extraordinary development of Jewish intellectual life.

The most influential representative of this intellectual golden age in Metz was Rabbenu Gershom. Born in Metz in 960, he became the leading figure in medieval Lorraine Judaism. Nicknamed the ‘Light of Exile’ by Rashi, who was one of his pupils, he ran a Talmudic school in Mainz. He was known for his rulings on the organisation of family life, in particular those prohibiting polygamy and the repudiation of a wife without her consent, which he replaced with divorce in due form. These decrees were gradually adopted by all Jewish communities.

This golden age came to an end in Metz in 1096 with the massacre of 22 Jews from Metz during the First Crusade, including Samuel Cohen, the leader of the community, which consisted of around a hundred families at the time. Many forced conversions took place at this time.

The yeshivot resumed their activities in the 12th century, under the influence of tossafist schools. Among his glorious pupils was Rabbi Eliezer, a tossafist who followed the teachings of Rabbenu Tam and was the author of one of the first attempts to codify Jewish law. Other scholars of the time were the tossafist David of Metz, Judah of Metz and Samuel ben Salomon of Falaise. The scholars of Lorraine maintained numerous intellectual exchanges with both French and German thinkers.

In 1237, foreign Jews entering Metz were obliged to pay special taxes. Until the expulsion of the Jews from the duchy in 1477, the Jews of Metz, like many other communities in France and Europe, were either warmly welcomed or encouraged to leave, depending on the fluctuating socio-economic assessments of political and religious leaders. The Jewish community in Metz gradually disappeared at the end of the 13th century. The only evidence of this period are the houses in the En Jurue street.

From the end of the 15th century to the 17th century, very few individual Jews returned to Metz and very small communities remained in the region. In 1567, the Marshal of Vieilleville granted the Jews the right of residence in Metz, so that they could take part in supplying the army with horses and wheat. Some of them settled in an alleyway (now called rue d’Enfer) between the En Jurue and the Récollets cloister.

By 1604, almost 120 Jews from Metz were living in the city. Fifteen years later, a synagogue was inaugurated. The community began to organise itself from this time onwards and was recognised by an order from the Duke of Valletta in 1624. The new arrivals settled in the Saint-Ferroy district in particular. The Jewish population grew throughout the century, rising from 398 in 1621 to 665 in 1674 and 1,080 in 1698. A Jewish cemetery has been existing for a very long time.

Heavy taxes were regularly imposed on the city’s Jews, as were restrictions on access to employment. In 1670, Raphaël Lévy was tried and executed at Glatigny, accused of ritual murder. Anti-Jewish measures were also taken. By 1717, the Jewish community in Metz had grown to over 2,000, making it the largest in France, thanks in particular to the arrival of German Jews.

The winds of the Emancipation of 1789 also swept through the Lorraine region. It was in this region, also inspired by the work of Mendelssohn and the Haskalah, that the periodical Ha-Meassef had the most subscribers after Berlin.

The minister, Malesherbes, set up a committee to this end, which included Isaac Berr from Nancy and Pierre-Louis de Lacretelle and Pierre-Louis Roederer from Metz. Pierre-Louis Roederer was the instigator of the competition organised by the Metz Society of Sciences and Arts, which asked candidates to consider the question ‘Are there ways of making Jews more useful and happier in France? Three dissertations were awarded the prize: those of Claude-Antoine Thiéry, Zalkind Hourwitz and, above all, Abbé Grégoire (1750-1831). The latter defended access to the rights and duties of citizenship for Jews before the National Assembly. His “Essay on the physical, moral and political regeneration of the Jews” was published in 1789 after winning the Académie prize. Abbé Grégoire also fought against black slavery.

The Emancipation of Jews decreed on 27 September 1791 gave them access to the schools, professions and the obligations shared with every other citizen. Following the Revolution, the Jews of Metz were granted French nationality in 1791 and freedom of worship in 1792. Isaïe Berr Bing became a member of the town council, symbolising this development. The Talmudic School, founded in 1821, became the Rabbinical School of France in 1829, a symbol of the great importance still attached to scholarship in the region. It was transferred to Paris thirty years later.

Throughout the 19th century, the number of members of Judaism in Lorraine fell, to the benefit of the Paris and Lyon regions. By 1853, there were just 1,300 Jews in Metz, three years after the consistory synagogue was rebuilt. One of the most important figures of this period, and proof of the dynamism of Lorraine’s Judaism, was Chief Rabbi Lazare Isidor (1813-1888), who was born in Lixheim and studied rabbinics in Metz. The mathematician and reformer Orly Terquem (1782-1862) and above all Samuel Cahen (1796-1862), the first Jewish translator of the Hebrew Bible into French and founder in 1840 of the journal Les Archives israélites de France.

When the 1870 war broke out, the Jews of Metz enlisted to defend France, as did Chief Rabbi Benjamin Lipman (1819-1886), who, together with the bishop, visited the Jewish hospice where soldiers of all faiths were cared for. Following the German annexation, Lipman and many other Jews opted for exodus. Victory in 1918 brought a peaceful return. The 1870 conflict and the First World War encouraged the arrival of Jewish refugees in Lorraine, particularly in Metz. The Jewish population rose from 2,000 in 1866 to 4,150 in 1931. One of the most important figures of the inter-war period was Chief Rabbi Nathan Netter (1866-1959), who was appreciated for his highly patriotic writings and his concern for the poor.

Following the German attack on 10 May 1940, Metz was bombed. On 10 June, Victor Demange (1888-1971) scuttled his newspaper Le Républicain Lorrain, which was not published until after the city had been liberated. On 14 June 1940, the Moselle prefect ordered the mayor to leave Metz, which had been declared an open city, causing panic among the population, who fled. The Germans entered the city on 17 June and carried out a systematic Germanisation, with Alsace and Moselle Lorraine being effectively annexed. German became the official language, streets were renamed and statues of French heroes were removed.

The expulsions and despoilments quickly began, as did the recruitment of young people and the total control of the Gestapo. During this time, Resistance movements sprang up in Metz and the surrounding area, notably around the teacher Jean Burger (1907-1945). Fort Queuleu was transformed into an internment and transit camp. Metz railway station was used as a transit point for many deportees from French camps to German camps.

Another war, another rabbi hero: Elie Bloch. Born on 9 July 1909 in Dambach-la-Ville, this son of a rabbi became a textile engineer before also opting for a career in the church. He was appointed deputy rabbi of Metz in 1935, in charge of youth affairs. With the help of Father Jean Fleury, chaplain to the Gypsies in the Poitiers camp, he organised the escape of many families to the countryside, as well as solidarity networks. On 17 December 1943, Elie Bloch, his wife Georgette and their 5-year-old daughter Myriam were deported and murdered in Auschwitz, as were thousands of other Jews from Metz. The street on which the synagogue stands now bears her name.

On 20 November 1944, the first American troops entered the north and south of Metz, accompanied by French soldiers. The city was liberated the following day. On 22 November, American General Walker handed the city over to the French authorities and Mayor Gabriel Hocquard resumed his duties.

The Jewish community struggled to rebuild after the war, having lost many of its members. In the 1960s, Jews from North Africa helped to breathe new life into the community.

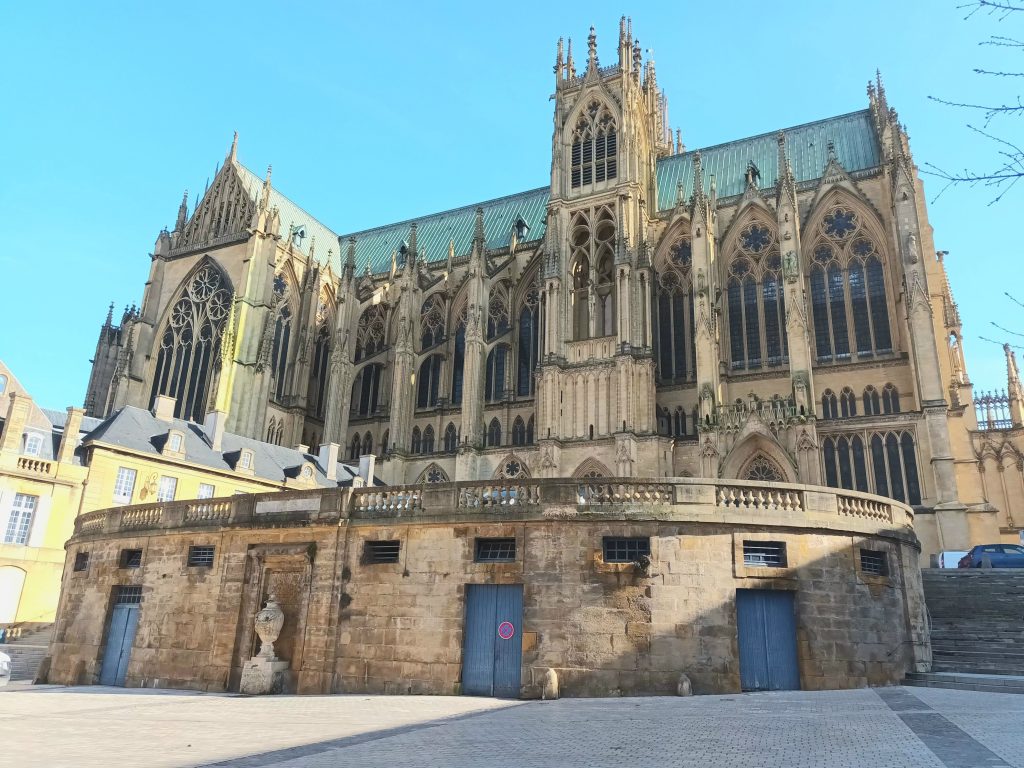

Just 700 m from the synagogue, opposite the town hall, is Metz Cathedral, probably one of the most beautiful in France, an impressive edifice 123 m long and 88 m high. Its 14-metre-high windows let in plenty of light and showcase the stained-glass windows created by numerous artists from the 13th century to the present day.

The stained-glass windows include those of a certain Marc Chagall.

In the two windows of the north apse, Chagall revisits episodes from the Bible, from the sacrifice of Isaac to the concerns of the prophet Jeremiah, including Jacob’s struggle with the angel, the Tables of the Law received by Moses and the song of David. A work dating from 1959.

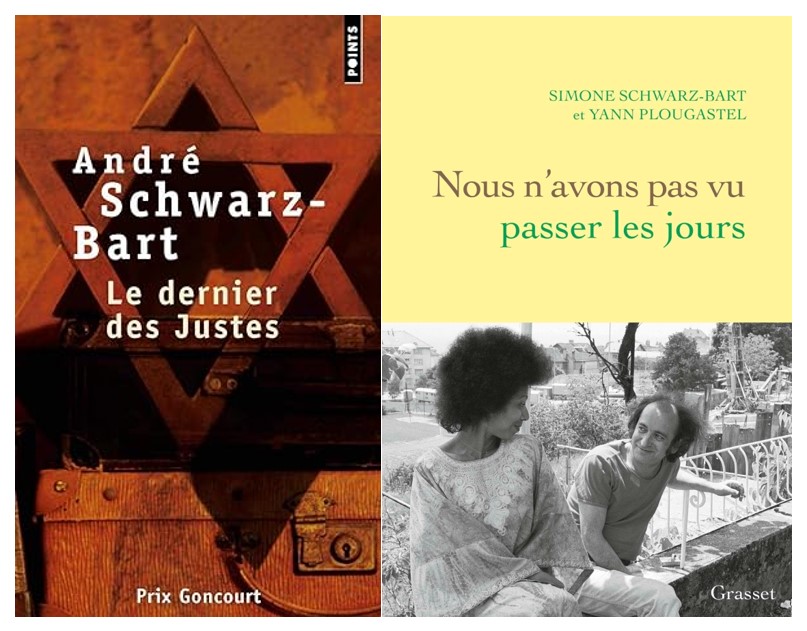

The year the Prix Goncourt (France’s most prestigious book award) was awarded for Le Dernier des Justes to the greatest contemporary Jewish figure from Metz: André Schwarz-Bart (1928-2006). The author was born in Metz on 23 May 1928 and spent part of his childhood in a house at 23 En Jurue. His parents and one of his brothers were arrested along with other family members and deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered. André Schwarz-Bart joined the Resistance in 1943. As an FTP fighter, he took part in the Liberation of Limoges.

After the war, he resumed his studies and worked in tailors’ workshops and in the factory. It took him eight years to write his book, a painful look at his past and the loss of his family. Following the publication of Le Dernier des Justes, he devoted himself to denouncing slavery and sharing the civilisations of black peoples. He co-wrote La Mulâtresse Solitude with Simone Brumant, whom he married in 1961 and with whom he moved to Guadeloupe in 1974. In a book published in 2019, Simone Schwarz-Bart looks back on their beautiful story of love and literature.

After two years of renovation work, the Metz synagogue reopened its doors in October 2025. More than 600 people attended the ceremony on Sunday, welcomed by a song performed by the Strasbourg synagogue choir. The site and the renovation work are symbolic of the new ‘Jewish Heritage Programme’, supported by the Heritage Foundation and the Edmond J. Safra Foundation, which aims to preserve and promote sites linked to Jewish history in France. The work was carried out both outside and inside the building.

Source: Le Républicain Lorrain

In Metz, we met Désirée Mayer, President of the JECJ-Lorraine, a key figure in the region’s cultural life, and one of the driving forces behind the JECJ-Lorraine board’s redesign of the room dedicated to the Jewish cultural heritage of Metz at the Musée de la Cour d’Or, Metz Métropole.

Jguideeurope: How did the project to create a room in the Museum devoted to the Jewish history of Metz come about?

Désirée Mayer: Like all good and lively projects, this one has several sources. There was a Jewish room in the museum, which was almost empty and unattractive. Before that, there was a local Jewish history that just wanted to be told, ritual objects that just wanted to embody it and all kinds of memorial traces that were looking for expression. Finally, there was the determination of the European Days of Jewish Culture – Lorraine team, bolstered by the benevolence and extreme competence of the management and staff of the Museum of the Cour d’Or, Metz Métropole. But we are not forgetting the inspiring model of the Rashi House in Troyes, or the many institutions, foundations and sponsoring associations that understood the value of the project and supported it.

What changes were made in 2023?

At the instigation of the Museum’s management, EDJC-Lorraine had photographs taken of the interior of the Metz Consistorial Synagogue and the Holy Ark, so that from the moment visitors arrive, they are greeted with a sense of interiority. With European aid and the support of patrons, in particular the Demathieu Bard foundation and the Bnaï-Brith Elie Bloch association, we were able to provide the museum with a touch-sensitive digital table, with software that allows visitors to immerse themselves in the Bible. Visitors, especially young people, love it. The room supervisors have become its dedicated mediators. Finally, the association exhibited a magnificent ‘Salon Judaïca’, created for the EDJC-Lorraine by an artist from Metz, Jean-Christophe Roelens. This artistic and educational exhibition, inspired by Rodchenko’s ‘Workers’ Club”, was enhanced for the occasion by a significant element symbolising Metz and Judaism.

Transmission has always been central to your commitment to teaching and cultural action. Is that what motivated your involvement in this project and in the JECJ?

More than any other project, this undertaking to refurbish the Jewish Room at the Museum of Metz fulfils our desire to pass on and share Jewish culture. The enduring nature of this prestigious institution, within an in-situ museum with a history spanning two millennia, is bound to resonate with the universal values of Jewish culture and spirituality. The large number of visitors, particularly young people, gives us hope that here, through this action, transcendence and descent can begin an infinite dialogue. This is exactly the eternal dream of the ‘passers’ and of those who wish to pass on their heritage.

What little-known place or person associated with this heritage do you think deserves to be highlighted?

Your question tortures me. For if the Eternal is One, all other references can only be plural. Without making any Christian claims, please allow me to evoke a trinity, or even a quartet. First, of course: the Metz consistorial synagogue, rich in history and symbolism, and which – thanks to the Heritage Foundation, the State and the City of Metz – is currently being renovated. This mid-19th century building will once again become a jewel. Secondly, I would highlight the stained-glass windows by Chagall in the Cathedral of Saint Etienne in Metz, particularly the atypical triforium in the left transept. Finally, I would choose the memoirs of the chronicler Glickel von Hammeln and, two centuries apart, the formidable Last of the Righteous by the Jewish author from Metz, André Schwarz-Bart.

This charming little town situated above the Drava river was an important Roman military site, which developed the town of Poetovium there. It was destroyed by the Huns in the 5th century and then rebuilt by the Slavs who settled there.

The Jewish presence in the town of Ptuj, best known today for its vineyards, probably dates from the end of the 13th century. The Provincial Museum also presents Jewish tombs from medieval times to the public.

The old Jewish street is now called Jadranska. The synagogue appeared to be located according to research by historians at number 9 Jadranska Street. It was replaced by a church in 1441, which was transformed into an apartment building in 1840.

Like Stanjel, Kidriveco, located a few kilometers from Ptuj, has a military cemetery accommodating soldiers who fell at the front during the First World War.

Abandoned, only a handful of graves remain visible in this cemetery . Among them, that of the Jew Isidor Lowi, who died in 1916.

Like Kidricevo, this small Slovenian village has an Austrian cemetery with graves of soldiers who died in the First World War.

Formerly a very large cemetery , abandoned, only part of its massive art deco entrance and a few graves remain visible. Among them, those of two Jewish soldiers.

A very pretty little marina near the Italian border, Koper was ruled by Venice from 1278 to 1797. The imprint of this presence is still very visible architecturally on buildings in the city and its cathedral.

The Jewish presence probably dates from the Venetian era. Dating back, it seems, to the end of the 14th century. A ghetto was established there at the beginning of the 16th century.

The ancient Jewish street (Zidovska ulica) is now called Triglavska ulica. This is where the medieval synagogue was also located.

The Jewish presence in Toulon dates back to at least the 13th century, but little written material from the period has been found on the subject. A general assembly of citizens took place in 1285, which included the names of eleven Jews.

As the Jewish population was small at the time, the city’s few Jews were not encouraged to live in a neighborhood and mostly lived in the central part of old Toulon. Near the current rue des Tombades. They also enjoyed many rights.

Following the massacre of forty Jews on the night of April 13-14, 1348, the presence of Jews was almost non-existent until the French Revolution. A few Jews were encouraged to convert, and a handful of others lived there temporarily.

So it was not until the 19th century that a small Jewish community was formed again in Toulon. Before the Shoah, around fifty families lived there, mainly from Alsace. Thanks to the arrival of Jews from North Africa in the 1960s, the community numbered 2,000 in 1971. A number that increased to 2,000 families by the turn of the 21st century.

The city of Toulon has two synagogues. The Centre Communautaire Israélite of Toulon , and the ACIT Synagogue .

Founded in 1243 by King Jacques I, the Jewish quarter of Perpignan, nicknamed the Call, developed between the Place du Puig, the Saint-Jacques church and the Dominican convent, as indicated in the sepcial edition of the Midi Libre newspaper devoted to the Jews of Occitania. This recognition allowed the Jews settled in the city since at least the 12th century allowed a fairly free life. There could be as many as 1,000 people living in this Jewish quarter, which represented 7% of the total population.

In addition to the synagogue, the butcher’s shop and other worship services, there was also a mill and a community armature, symbol of the place given to Jewish life in the city. Jewish cemeteries were located at the Porte de Canet and near the “stone bridge”.

Recent discoveries attesting to this presence were made possible by archaeological excavations starting in 1997 and continued until 2018, the aim of which was in particular to find the traces of an ancient mikvah. It appears that the mikvah was attached to a synagogue that has also disappeared.

Jewish intellectual life flourished in the city, as did other communities in the region. Menahem Haméïri was one of the important figures of medieval Judaism in Perpignan. A man very invested in Judeo-Christian dialogue and in the preservation of regional customs.

At the start of the 14th century, around 100 Jewish families lived in Perpignan. But over the course of the century that number declined, even before the expulsion of the Jews of 1493, following the order for the expulsion of Isabella and Ferdinand from Spain. Only 39 individuals lived there that year.

The new synagogue in Perpignan, inaugurated in 2018, bears the name of Haméïri. 700 to 800 families today form the Jewish community of the Pyrénées-Orientales region.

Continuing her testimonies to schoolchildren, Esther Senot, a 96-year-old Holocaust survivor, met with students from Lurçat High School and Camus Middle School in Perpignan in September 2024. She fulfilled a duty to remember that she had made to her sister in Auschwitz, which has become all the more important since the exponential rise in anti-Semitic acts inspired by 7 October. Speaking to the pupils, she recounted what happened to her during the Holocaust, but also her peaceful childhood in the working-class neighbourhood of Belleville in the 20th arrondissement of Paris on the eve of these horrors.

Sources: Times of Israel

A port city, the Jewish community has been present in Volos since the Antiquity era. Probably from the 2nd century BC, ancient tombs attesting to it, according to historians. But the certainties between experts on the exact moment concerning this city are not yet established.

Benjamin de Tudela noted the presence of Jews in the region in his famous travel accounts. Over the centuries, a number of them worked in trade-related activities, including textiles and tobacco. They largely participated in the economic development of Volos.

The city had 35 Jewish families in 1850. A synagogue was built there between 1865 and 1870. A school of the Alliance Israélite Universelle opened there a year earlier. But it closed in 1878.

Following anti-Semitic acts at the turn of the century, much of the community settled in Salonika. But the city still had a thousand Jews in 1913.

Of the 882 Jews present in Volos in 1940, many managed to escape before the arrival of the Axis armies, with the help of locals and religious authorities. During the occupation by Italian troops, the Jews were relatively safe. However, when the German troops arrived, 130 Jews were arrested by the Nazis in March 1944 and deported.

Many Jews joined the Resistance, including aiding the British Army in its actions against the Germans. Rabbi Moshe Pessah worked in coordination with Archbishop Joachim Alexopoulos and the National Liberation Front to find a sanctuary for the Jews of Volos in the surrounding mountainous regions and the villages there. Thanks to this effort, three-quarters of the were saved.

The synagogue was destroyed by the Nazis and rebuilt after the war, but was nevertheless damaged again by an earthquake in 1955. A smaller synagogue was built there and is still in operation today.

The old Jewish cemetery was located in the Neapolis district. The new Jewish cemetery is at the intersection of Taxiarhon and Paraskevopoulos streets.

A Holocaust Memorial is located where the ancient synagogue used to be.

In the aftermath of the war, 565 Jews lived in Volos. A figure that declined to 210 in 1967. Only a hundred are part today of the Jewish community .

As in many European cities, and particularly in many Greek cities, Volos has been the victim of anti-Semitic acts. These have been fuelled by significant movements exploiting the conflict between Israel and Hamas since the pogrom of 7 October. Among these numerous acts, a Jewish cemetery in Volos was vandalised.

The Jewish presence in the city of Trikala seems to date from the Byzantine period. But there is not much documentation to confirm this presence. The arrival of Jews from Spain following the Inquisition, as well as Jews from Portugal, Hungary and Sicily, increased the number of members of the community. A large part of these Jews worked in the weaving of wool.

In 1749, a fire ravaged the city and the Jewish quarter as well as the synagogues were seriously damaged. The community grew again with the liberation of the city from Turkish forces and its integration into the Greek kingdom. With the creation of a talmud torah and the renovation of its synagogues.

According to the 1907 census, there were 110 Jewish families in the city of Trikala. A figure which increased twenty years later to 120 families.

At the outbreak of World War II, the Greek army counted many committed Jews, including a significant part from Trikala. During the Holocaust, many of the 500 Jews were able to escape. On the night of March 23, 1944, 112 were arrested and deported. Only about ten survivors returned to Trikala at the end of the war.

In the aftermath of the war, the community consisted of 73 families. Renovation work was undertaken, particularly at the city’s Jewish cemetery. Only 101 Jews lived in Trikala in 1967. At the end of the 20th century, the Jewish population numbered around 40.

The Jewish Quarter had three synagogues, the Kahal Kadosh Yevanim, the Kahal Kadosh Sephardim and the Kahal Kadosh Sicilianim. The large and old Kahal Kadosh Yevanim Synagogue was destroyed in 1930 due to its condition.

A new synagogue was built but quickly damaged by the German occupiers during the war. The post-war renovations were again damaged, this time due to an earthquake in 1954. It was rebuilt and opened in 1957.

The small synagogue which was on Kondyli Street suffered the same damage during the war and the earthquake. It was reused to house the victims of the earthquake.

The Jewish cemetery is located in the north of the city, close to the motorway connecting Trikala to Kalambaka. Some tombs are over four centuries old. Renovation work has been undertaken on several occasions following natural or intentional deterioration. The synagogue also suffered damage linked to anti-Semitic acts in 2019. In 2020, this was again the case for the cemetery.

The re-dedication of the Kahal Kadosh Yevanim synagogue took place in 2022. It was part of a three-day celebration that included a concert, a dedication ceremony and an exhibition in a local museum about the restoration project.

The Jewish presence in Larissa seems to date back to ancient times. Archaeological excavations indicate that this presence has probably been continuous for 1900 years. Following the Spanish Inquisition, Jews settled there. Among them are many scientists, philosophers and entrepreneurs. They thus participated in the development of the whole city.

The community is known for its large number of Talmudists. Among them, Joseph Ben Ezra. Isaac Shalom, a philanthropist from Larissa, supported a yeshiva in Salonika. Jews from Puglia and the Peloponnese also settled there over the centuries.

The Turkish occupation, which lasted until 1881, interrupted this prosperity, the occupiers establishing a severe regime vis-à-vis the entire population of the city. In the middle of the 19th century, the community consisted of 2000 people. A school of the Alliance Israelite Universelle was present during this period. Most of them lived and still live in the district of Exi Dromoi, in the center of the city, without this being a ghetto, the different populations coexisting in good harmony.

On the eve of World War II, there were seven synagogues in the city. During the Holocaust, 950 of Larissa’s 1,175 Jews were able to escape into the mountains. A good part joined the maquis and fought arms in hand with the Resistance movements. The vast majority of those who remained were deported and exterminated.

A monument to the Jewish Martyrs was erected in 1987 on the Plateia Evraion Martyron Katohis. A monument in homage to Anne Frank was erected in 1999 on a place renamed the name of the young girl, in memory of the children who died during the Shoah.

A few hundred Jews still lived in Larissa at the end of the 20th century. There remains the Etz Hayyim synagogue . Built in 1860, it was used as a stable by the Nazis. It was renovated after the war and rebuilt as it was. On the other hand, very old manuscripts and books were destroyed by the occupants. It still hosts prayers today on Friday evenings and Saturday mornings, as well as on Jewish holidays. Renovation work was again undertaken from October 2019 thanks to donations.

A Jewish school was opened in 1931 and remains today the only Jewish public school in the country, welcoming students of various faiths. It was closed in 2017 due to the dwindling number of students. Young people from the community meet there once a week for cultural activities. The Larissa Community Center was built in 1954.

As in many European cities, and particularly in many Greek cities, Larissa has been the victim of anti-Semitic acts. These have been fuelled by significant movements exploiting the conflict between Israel and Hamas since the pogrom of 7 October. Among these numerous acts, a monument in Larissa commemorating the victims of the Holocaust was vandalised and the synagogue damaged in 2025.

An old Jewish cemetery can be found in the Neapoli district and was in use until 1900. The new Jewish cemetery is located near the Christian cemetery.

The great peculiarity of the Jewish community of Chalkis is that Jews lived there uninterrupted for over 2,500 years! Probably one of the few in Europe in this case. They settled mainly in the northeast of the fortress. 2000 years ago, Flavius Joseph already mentions the presence of Jews in the Greek city in his work. The same goes for the traveler Benjamin de Tudela twelve centuries later.

In 1159, he noted the presence of 200 Jews in the city, mainly silk manufacturers and dyers. And suffering from no discrimination. They all spoke Greek and had a synagogue.

From the 13th century, during the Venetian conquest, the fate of the Jews was very different. They suffered discrimination and had to live in a ghetto. Additional taxes and a ban on obtaining nationality added to this discrimination. Then in 1402 the ban on buying land outside the ghetto.

From 1470, the city came under the control of the Ottoman Empire, which perpetuated a great massacre of the villagers there. The Jews suffered the same suffering and exploitation as during the Venetian occupation.

In 1840, when the city was part of Greece, the community numbered 400 people.

The synagogue , located on Kotsou Street, was destroyed in 1854 and rebuilt on the same spot the following year with the help of the Duchess of Plaisance, Sophie de Marbois. She is also known for her many philanthropic activities across the country. Unfortunately, many archives and parchments disappeared under the flames.

The old and new Jewish cemeteries can be found on the Street of the Jewish Martyrs, a street renamed by local authorities in recent years. At the end of the 20th century, a great work of restoration of the tombstones was undertaken.

It was estimated that 325 Jews were in the city on the eve of World War II. One of the first Greek officers to drop arms in hand was Colonel Mordechai Frizis.

A hero of the First World War, he also distinguished himself in the Second, during the Italian attack of 1940-1. After pushing back the Italian forces on the bridge over the Thiamis River, they counterattacked from the air. He remained on the battlefield alongside his men and died of his wounds.

Buried on the battlefield during the war, his remains were buried again in 2004 in the Jewish cemetery of Salonika with military honors in the presence of Greek President Kostis Stephanopoulos. His grandson, who bears the same name as him, in homage to the hero, was the rabbi who officiated the ceremony.

Following the German invasion, the Jews took refuge in the hills, with the help of locals and resistance fighters. Others fled to Palestine through Turkey. But a good part of the Jews were deported by the Nazis.

A monument has been erected in memory of the victims of the Holocaust where the busts of Bishop Grigorios and Colonel Frizis can be seen. The latter is also by a statue near a Chalkis bridge, a street as well as other monuments in Athens.

By the turn of the 21st century there were only around 60 Jews living in the city, most of them settling in Athens or abroad.

Turku was an important city when Finland was part of the Kingdom of Sweden before independence. It has a Jewish presence dating back to the 19th century, with some dating back to 1853.

Following the city’s donation of a plot of land in 1900, the Turku Synagogue was built in 1912. Mainly architecturally influenced by Byzantine art and Art Nouveau, which was very popular at the time. The synagogue is Orthodox, like the one in Helsinki, despite the fact that most Jews in Turku are not very religious.

The community center, which is right next to the synagogue, dates from 1956. In the 1950s, the community had 350 members. However, over time, many people moved to Helsinki or Israel.

The city of Turku also has a small Jewish cemetery .

Four hundred Jews lived in Posquières in the 12th century, according to the Benjamin of Tudela’s travels. A city where, as the author recounts, a community very much invested in study and research was maintained. Like other towns in the region at the time.

Benjamin of Tudela notes the presence of a Talmudic school run by Rabbi Abraham ben David. Which wouldn’t be just a local reference, but an international one, with people willing to travel long distances to ask him a question.

It also housed many European students without resources. His comments have also been incorporated into the Talmudic corpus, as recalled in the book Les Juifs de Montpellier et des terres d’oc by Michaël Iancu.

His son, Isaac de Posquières, is considered the “father of Kabbalah”. His comments and questions on the notion of divinity and other mystical matters are respected by these students who will continue to develop the study of Kabbalah in the region.

In 2019, a commemorative stele was unveiled in the ancient Jewish cemetery of Vauvert, the current name of the town of Posquières.

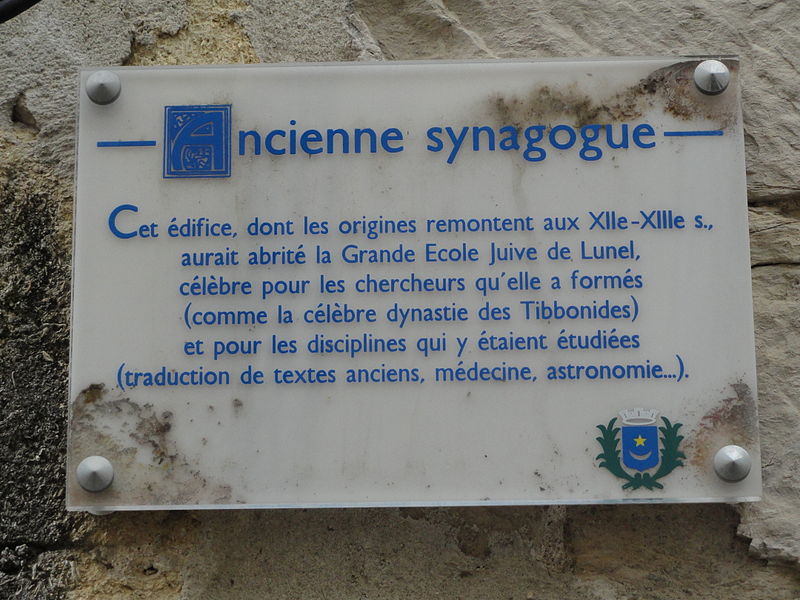

In his Book of Travels, Benjamin of Tudela mentions the Jewish community of Lunel. As well as the active study of texts by students and the spiritual leader Rabbi Meshoullam. According to Tudela, Meshoullam was surrounded by his five children during his activities. Children who later became rabbis: Joseph, Isaac, Jacob, Aaron and Asher.

For this community of only 300 members, according to the traveler’s writings which are widely used by many historians as an important source of reference for this era, it is all the more remarkable to see him mention the presence of other rabbis in the city. Further evidence of the intellectual golden age of medieval Judaism in Lunel and in the region of Languedoc in general.

According to the book Les Juifs de Montpellier et des terres d’oc written by Michaël Iancu, Meshoullam encouraged the development of literary and scientific knowledge in the region. Notably, by asking Judah ibn Tibbon to translate Bahya ibn Paqqûda’s work from Arabic to Hebrew.

Jewish and Arabic literatures being very close in their development during this golden age. Meshoullam would thus have encouraged many authors and translators in their work and their sharing way beyond a simple regional project.

Concerning the five sons of Meshoullam mentioned earlier, some turned towards science and others towards mysticism. Asher led an ascetic life, becoming a great Talmudic reference and the author of halachic works. This did not prevent him, on the contrary, from taking a close interest in Neoplatonic philosophy.

As for his brother Jacob, he also led a life as a Nazir ascetic, devoting himself entirely to studies. He was one of Abraham b. David de Posquières’ students.

Jonathan ben David ha-Cohen succeeded Rabbi Meshoullam as the supreme rabbinical authority of the city of Lunel. Author of commentaries on the Talmud and the Mishnah, he also maintained a regular correspondence with Maimonides.

A letter addressed to Maimonides was found much later in the Guenizah of Cairo and is currently kept at Oxford’s Library. Jonathan and his students asked him astrology questions and asked him for the possibility to obtain a copy of Maimonides’ Guide to the Perplexed.

Judah ibn Tibbon (1120-1190), a doctor fleeing the intolerance of the Almohads, had as his main baggage when he settled in Lunel in 1150, books in Hebrew and Arabic, probably from Granada.

Apart from Meshoullam’s commission for ibn Paqqûda, he translated many Judeo-Arab works throughout his life. Among his translations, we can note those of texts by Saadia Gaon and Juda Halevi. He was rightly nicknamed “Father of Translators”.

His son, Samuel ibn Tibbon (1150-1232), entered into posterity for having translated Maimonides’ Guide for the Perplexed. He recounts in the prologue to his translation how the rabbis of Lunel were impatient to receive Maimonides’s work and endeavored to devote themselves to facilitating the rapid and complete translation of the work.

Paul B. Fenton proposed a translation of correspondence from Maimonides’s son revealing the father’s strong esteem with the scholars of Lunel. Ibn Tibbon, translated other Arabic and Greek works, continuing the spirit of sharing of the Golden Age.

Today, medieval remains of an ancient synagogue can be found at the Hôtel de Bernis. A plaque was placed on one of its walls.

Once a city and now a village, Michaël Iancu describes in his book Les Juifs de Montpellier et des terrains d’Oc the contribution of Lattes to the development of Montpellier in the Middle Ages and its importance in the region’s Jewish cultural and intellectual heritage. The surname “de Lattes” was frequent at the time among the Jews and probably carried because of their origin in this city.

Among them, Isaac de Lattes who lived in the 14th century. A Barcelona-trained physician, he is the author of a Treatise on the Stomach and a treatise on fever entitled Treatise of Isaac de Lattes. In 1372, he wrote the Kyriat Sefer (City of the Book) which presents the Languedocian Jewish authors of the Middle Ages. Undergoing this troubling period of exiles and sometimes authorized returns during the 14th century, Isaac wishes to pay tribute to these great figures and to signify their contribution to the region in its intellectual and scientific development.

Isaac de Lattes of course refers to ibn Tibbon father and son, to Meshoullam and his descendants, as well as other local figures, but also connections between Languedoc and Spain. A work that ends with these disturbing words: “Finally we come to the year 1372, the time of great wars and massacres, when, of course, schools were interrupted.” Books and the will of sharing padlocked by the sword and geopolitical wills.

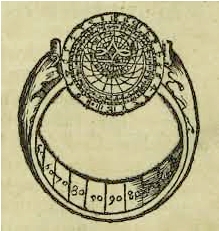

Bonet de Lattes (1450-1510), who was born in Aix, became a great physician in Rome, in the service of three popes. Author of an Astronomical Ring in Latin, the famous doctor will be cited by Rabelais. His son, Immanuel de Lattes, would also become a doctor and return to the family’s homelands by practicing in Avignon.

Located about forty kilometers from Chisinau, Orhei is best known by tourist guides for its troglodyte monastery, located on the outskirts of the city in Orhei Vechi, very interesting to visit. It is also considered one of the major tourist spots in Moldova.

The city also has a rich Jewish past, many traces of which remain today. As you exit Chisinau on the Orhei Road, ask to stop at the monument erected in 1991 at the site of a site where mass executions of Jewish citizens, exploited in a nearby quarry, took place. To get to Orhei from Chisinau, you can either use a marshrouthka (collective minibus) specifying that it is in Orhei, and not in Orhei Vechi that you want to go, or take a taxi. In both cases, the easiest way is to leave from the Piata central bus station, the central market. Allow around half an hour by taxi and an hour by marshroutka. Finally, do not hesitate to contact the Chisinau Jewish Cultural Center before your visit, which can put you in touch with representatives of the city’s community.

As with the rest of Bessarabia, it was especially from the beginning of the 19th century that a significant Jewish presence developed in Orhei. Meir Dizengoff, the first mayor of Tel Aviv, was born in one of the families in this region in 1861. At the start of the twentieth century, the city had some 7,000 Jews for a total of 12,000 inhabitants, or about 65% of the population. The Jewish community of Orhei now numbers only a few dozen people, with the majority of the city’s Jews who survived the Holocaust having left for Israel or the United States after the fall of the Soviet Union.

You can start your walk through Jewish Orhei by heading to number 15 Srisului Latin Street, where one of the city’s former synagogues is located, now converted into a shopping center. If the building no longer presents any exterior symbols attesting to its previous functions, its general architecture is typical of those of the region’s synagogues built during the 19th century. Opposite the synagogue is now the municipal stadium, where the Jewish asylum for the elderly was previously located.

You will then be able to stroll on both sides of Vasile Lupu Street, in the streets of the old town, which have kept the shtetl if not the spirit, at least the appearance. Cobbled streets, small one-story houses dating from the Tsarist or Romanian period, backyards serving as storage rooms and henhouses, the decor has not really changed in Orhei since the days when Jews made up the majority of the city’s population city. The latter had their hospital , located around 127 Vasil Lupu Street which you can visit; the premises have remained intact and have now been integrated into the city’s public hospital.

Going up Lupu Street, at number 62, you will come across the only Orhei synagogue still in operation, intermittently. This is where the city’s now small community gathers for the holidays. At the crossroads with Lupu Street is Constantin Stamati Street, which you will take to reach the Orhei Cemetery , one of the oldest in Bessarabia. Established over four centuries ago on a hill on the edge of the city, this cemetery contains more than 25,000 graves and is one of the most moving and best-preserved cemeteries in Bessarabia. We will highlight the presence of two monuments in memory of the victims of the Shoah, one fairly classic, the other more original, bearing in Russian and Hebrew the names of a hundred Jews from Orhei killed by the soldiers. Romanians and Germans during the Second World War.

At number 95 rue Lupu is the House of Haïm Rappoport . A Jew from Orhei, H. Rappoport, after being deported by the Romanians with his whole family to the Domanovka camp, in the Bug region, returned to his hometown, before being exiled by the Soviet authorities in the Irkutsk region, in Siberia, until 1956. In 2003, his son Semeon managed to recover from the Moldovan government this humble home from which the Rappoport family had been expropriated.

Heading back down to the city center, slightly set back from Vasile Lupu Street, at 23 Renasterii Nationale Street is the Orhei Ethnographic Museum , the visit of which is well deserved. Located in a small building in the Neo-Roman style, the museum provides interesting material on the history of the city, particularly during the Second World War.

You can end your walk in Orhei with a lunch at the Primavera restaurant , 152 Vasile Mahu Street. Located in an elegant Art Deco building built at the beginning of the twentieth century, it has been in operation since 1914 and is one of the prides of the city.

At the start of the twentieth century, Kishinev had more than seventy synagogues and about twenty yeshivot. Unlike many other cities in the Russian Empire, the Jews of Kishinev did not live in a ghetto, except during the dark years of the Holocaust.

While the working-class suburbs of the lower town concentrated the bulk of the Jewish population, some had also taken up residence in the upper, more bourgeois part, where the majority of the embassies are today. The Moldovan capital therefore does not have a Jewish quarter to speak of, and the many sites you can discover are therefore scattered all over the city center.

You can start your walk in Jewish Chisinau with a discovery of the city’s large market, Piata centrala , a pleasant maze of a thousand flavors where it is possible to taste the products of the surrounding countryside, often sold directly by their producer. Honey, cheeses, dried fruits, wines, it is a pleasant Moldovan gastronomic panorama that you can discover in Piata Centrala. Strengthen your strength by feeding yourself, among the porters and in the shade of the acacias, a few shashliks embellished with kvass, this refreshing wheat-based drink, then head towards the city center, taking Armeneasca Street , the Armenians Street, until the intersection with Columna Street . You will quickly come across the intersection with Chabad Liubavici Street, where Chisinau’s only synagogue is still open permanently at number 8. Built in 1888 by architect T. Ghinger, this synagogue, sometimes referred to by its Yiddish name Gleizer Shil (Glaziers’ Synagogue), is currently run by the Lubavish community, which has a Beith Chabad nearby. Relatively humble on the outside (it was partly destroyed during World War II), its central hall has been very well restored.

Going up Chabad Liubavici Street, you will arrive on Vasile Alexandri Street, which you will then descend a few steps to find yourself in front of one of the most significant remains of the Jewish history of Bessarabia, those of an impressive yeshivah , whose facade extends over about fifty meters. This was built in 1860 by the city’s Hasidic community – Bessarabia was indeed a major pole of influence for the thought of the Baal Shem Tov school, seeking to counter the growing influence of the Haskalah on the community. Kishinev’s yeshivah was considered one of the most important in the southern part of the Russian Empire and attracted students from Bessarabia as well as Podolia and other areas now in Ukraine. Massive and in relatively good condition, the Chisinau yeshivah was still used as a warehouse for local scrap dealers. Now classified as a historical monument, it is awaiting rehabilitation.

Near the old yeshivah is the Chisinau ghetto, in fact the real ghetto the part of the city in which the Romanian authorities had concentrated the Jewish population during the Second World War, from 1941. A monument to memory of victims of the ghetto was erected in 1993 on Ierusalim Street , in the heart of this district. Contrary to certain cities in Europe in which the ghettos have been the subject of major rehabilitation programs, that of Chisinau, for lack of interest and especially for lack of funds – Moldova has long remained the poorest country Europe – has remained largely intact. As we walk around it, we sometimes find it hard to imagine that decades separate us from old black and white photos seen in the museum or with a distant relative. Discovering Jewish Chisinau is like getting lost and strolling through the cobbled streets of the city center where, less than a century ago, the vast majority of inhabitants were Jews and the backyard lingua franca, Yiddish. Dina Vierny, born in Bessarabia in 1919 and above all famous for having been Maillol’s muse, has collected and performed very beautiful songs from Russian prisoners, the moving melodies of which it almost seems that still resonate here, in the streets of old Kishinev.

In another register, you can also wander in this district after being impregnated with Geb mir Bessarabia, the famous Yiddish actor and singer Aaron Lebedeff, born in Gomel (current Belarus) in 1873.

Not far from Ierusalem Street, is on Diorditsa Street, the building of the former Lemnaria Synagogue (lumberjack synagogue, a wood market existed not far from the synagogue), an imposing four-storey building built in 1835. Nationalized during the Soviet period, it was returned to the community in 2005, fully rehabilitated, and now houses the Jewish cultural center Kedem , offering many activities. Do not hesitate to go inside and ask for the program; you will surely have the chance to attend a play in Yiddish or a concert of klezmer music. In the basement, the recently reorganized Jewish Museum of Chisinau offers a bright and comprehensive panorama of the Jewish history of Moldova in all its dimensions and is of great interest not to be dedicated solely to the history of the 1903 pogrom and of the Shoah. The cultural center can also be of great help to you if you are looking for family archives, places where your ancestors lived or cemeteries where they would be buried.

In front of the cultural center, you can visit the Jewish library of Chisinau, with a collection of tens of thousands of works in Yiddish, Russian and Romanian but also in French, English and German, and including the entrance is decorated with a plaque in memory of the Moldovan Yiddish-speaking writer Yechiel Shraibman.

Take some rest in one of the terrace cafes pleasantly located on Diorditsa Street, the city’s only pedestrianized street, and you are full of energy to continue your day. Nearby, at 69 Vlaicu Pircalab Street is the building of an ancient Talmud Torah . Cross the cathedral park towards Alexandru Cel Bun Street, where at number 117 there was a School for young girls from working class families.

Then go up Columna Street, where, at number 150, you will find the buildings of the old Yavne Synagogue and the old Jewish hospital in Chisinau. Built at the beginning of the nineteenth century, it was fully transferred to the Jewish community in 1870 and could then accommodate up to 200 beds. It’s worth going inside and taking a look at this collection of old buildings and its interior garden: the decor has hardly changed.

Go up to the end of Columna Street, then straight on until Calea Iesilor Avenue where you will quickly come across a large park, the Alunelul Parcul . It houses the monument inaugurated in 1993 in memory of the victims of the Chisinau pogrom, buried in the Jewish cemetery which at the time extended to the site of Alunelul Park. Going up Milano Street, you will come to the Jewish cemetery, one of the largest in Europe, measuring around 10 square kilometers. Huge labyrinth of trees, weeds, and gravestones; there are some 24,000 bearing the names of the deceased in Yiddish, Romanian or Russian depending on the date on which they were buried; the Jewish cemetery would house in particular, under a brick building that you can easily distinguish the desecrated Torah scrolls that would have been buried there the day after the pogrom. About a ten-minute walk left from the entrance to the cemetery is the incredible remains of a late-19th-century building in which tahara was practiced and whose heavy, rusty doors still bear the star of David. Save time and energy to visit this place in ruins, whose solemnity has remained intact, and which will be the highlight of your visit.

From the cemetery, the easiest way to get back to the city center is to take one of the trolleybuses running Strada Iesilor. Going down to Stefan Cel Mare Park , you can pass the National Museum of Moldovan History , which also has some collections dedicated to the history and life of Bessarabian Judaism. Then take Mihail Kogalniceanu Street until you reach the intersection with Tighina Street, which you will take to the corner with Alexei Sciusev Street . At this crossroads is the building of the old hay synagogue, so named because it was then located, when it was built in 1886, near a cattle market.

To end this busy day, you can spend the evening at the Forshmak restaurant , located near Negruzzi Square, not far from the train station and the church from which the 1903 pogrom was initiated. The Forshmak restaurant, although not kosher, offers many dishes of Jewish inspiration from the region, starting with the forshmak itself, herring cream, whose original recipe comes from Odessa but which seems to have been followed. in Bessarabia. If you want to enjoy authentic Moldovan cuisine, you will find what you are looking for in one of the many quality restaurants located around Stefan Cel Mare Park.

Few Jews have inhabited Albania through the centuries, but as noted in the country’s overview page, it is the only European country that sharply increased its Jewish population during WWII thanks to the courageous welcome of refugees coming from surrounding regions.

In 1939, for example, around 100 Jewish families settled there, two-thirds of them in Tirana. Later that year, around 100 German Jews were able to take refuge there as well.

Although the country had 200 Jews in 1969, most of them living in Tirana, there was no organized community or rabbi. Following the fall of the Berlin Wall, most Albanian Jews emigrated to Israel.

In 1996, 25 Jews were registered in Tirana. An emissary from Chabad, based in Greece, provided a minimum service to the Hechal Shlomo synagogue in Tirana.

Jewish revival in Tirana

In 2010, Rabbi Joel Kaplan, who previously served as Chabad’s envoy to Salonika, was appointed in the presence of Albanian Prime Minister Sali Berisha and Israeli Chief Rabbi Shlomo Amar, as well as local representatives of the Muslim and Christian cults. A first for 70 years.

A Jewish Community now serves the needs of Tirana’s Jews.

A Memorial was inaugurated in 2020 honouring the Jewish victims of the Shoah and the Albanian Righteous who saved them. The inauguration took place in the presence of Prime Minister Edi Rama.

Among the 50 to 200 Jews present in Albania, most live in Tirana.

The large city of Vlore was the center of Albanian Jewish life in modern times, although little remains of it today.

Near the Historical Museum of the city is the Street of the Jews . A plaque on one of the buildings pays homage to the Jewish inhabitants of Vlore. An adjoining plaque indicates that the Street of the Jews is “protected by the state”.

Honoring Albanian rescuers

The Street of the Jews was so named after a ceremony where a plaque was unveiled honoring the rescue of the region’s Jews by Catholic and Muslim inhabitants during the war. Among them Anna Kohen, who with her family was in hiding and then took refuge in the United States, and was the source of this recognition.

Then head to the Muradie Mosque . Adjacent to the building, you will notice a beautiful three-storey building. This building, built in 1928, was successively one of the city’s three synagogues, a library, and then a private school. It is still owned by the Jewish community.

Sarande, a charming seaside resort in southern Albania, is located on a bay lined with beaches and a promenade.

In the center are the archaeological remains of a 5th-century synagogue, as well as more recent ones from an early Christian basilica. Complex mosaic floors remain. The 16th century Lëkurësi Castle is perched on top of a hill above the town.

Archaeological wonders of Sarande

Discovered in the 1980s, then excavated and restored in the early 2000s, the Sarande synagogue dates from the 5th century and belonged to a prosperous and prominent community, as its location in the heart of the old town indicates. Visitors can now admire the mosaics, including a menorah and what looks like the Holy Ark. In the 6th century, the synagogue was transformed into a basilica – then destroyed, probably during the Avaro-Slav attacks of the years 580-585. You will find more detailed information and photographs at the city’s Archaeological Museum .

The old town of Berat is a World Heritage Site, known as the “City of a Thousand Windows”. Indeed, the white houses of the city and their windows framed in dark wood seem to be superimposed on each other.

Perpendicular to Antipatrea Street , you will find the Jewish Street.

Jewish museum

But above all, you will find in Berat the only Jewish Museum in Albania. The Solomon Museum was created in 2018 by Simon Vrusho. This enthusiast collects and exhibits hundreds of documents, photographs and artefacts retracing 2,000 years of Jewish history in Albania.

The Solomon Museum, also tells the story of how Albanians of Muslim and Christian faiths saved Jews during the Holocaust. After Vrusho’s death, the French-Albanian businessman Gozmend Toska financed its reopening and expansion to another part of the city.

Sabbatai Zevi’s burial place?

It should also be noted that some sources claim that the false messiah Sabbatai Zevi would be buried in Berat. this explains the establishment of a Deunmé community in Berat in the 17th century.

The city remained a place of pilgrimage for Zevi devotees until the 20th century. You can visit the supposed tomb of the mystic in the Sultan Mosque , you will recognize it by its Turkish calligraphy.

On the other side of the courtyard is a smaller mosque. Above the front door you will notice floral designs that resemble stars of David – perhaps indicating that this building was once a deunme place of worship.

Born in Smyrna (now Izmir) in 1626, into a family of clothiers from the Peloponnese, an enthusiastic Kabbalist, Sabbataï Zevi, convinced of being the Messiah, led the Jewish communities of the Ottoman Empire into turmoil. For its most penetrating modern exegete, Gershom Scholem, this religious and insurrectionary movement developed against a background of cabalistic mysticism, the dominant form of Jewish piety of the time.

From the expulsion from Spain, Jewish thinkers wondered about the significance of such a catastrophe, relating it to the destruction of the Temple in Jerusalem. “I think that these trials,” said a rabbi in Rhodes in 1495, “are the birth pangs of the Messiah. So one can understand the enthusiasm and the hopes which sparked the dazzling Messianic movement of the Smyrniot, despite his excommunication by the rabbis of Jerusalem. In 1665, Sabbataï Zevi decided to go to Istanbul. Arrested by the Ottoman authorities, forced to choose between martyrdom and conversion to Islam, the so-called Messiah chooses to bow.

Some of his supporters see this apostasy as an essential step in the achievement of his mission and also convert to Islam, while maintaining their Jewish faith and practicing the rites in secret. This community of deunmés (“those who turned”) retreated to Turkey at the end of the Empire. Some large military families still play an important role in publishing or industry today. Hidden for a long time, remained discreet during the first seventy years of the secular Republic founded by Mustapha Kemal, the Turkish deunmés began to openly claim their identity and their history.

The presence of Jews in the city of Dundee dates back to the middle of the 19th century when fabric merchants from Hamburg came to do some shopping in the city. Some settled there and quickly assimilated into the population.

Dundee’s first synagogue was built in 1878 at Murraygate. The Jewish Year Book of 1901 lists 127 Jews in Dundee. The synagogue moved to Meadow Street in 1920 thanks to the donation of Sir Maurice Bloch. Among the famous contributors to the construction of the synagogue was a certain Winston Churchill, who was then Member of Parliament for Dundee.

However, fifty years later, the community numbered only about thirty people. The district of Dundee where the synagogue is located is completely renovated and it destroyed. Another venue for prayers between 1978 and 2019. There is also a Jewish cemetery in Dundee.

Dundee Jewish Community has been renamed Tayside & Fife Jewish Community .

France’s third most populous city since 2025, the pink city (named after the bricks on its buildings) is best known for its ability to cross time, from its ancient religious buildings to its aeronautics and space industry. Not forgetting, of course, its gastronomic specialities, its universities, its glorious rugby team and its bridges that facilitate space-time crossings…

Administrative archival documents date the presence of Jews in Toulouse to the 800s. The city of Toulouse is part of this flourishing Jewish life from the Middle Ages close to Spain and Languedoc. As confirmed by the presence in the 11th century of Moses Hadarshan (originally from Narbonne) and his son Judah, whose pupil, Menahem Bar Helbo, will introduce Rashi to Mediterranean Jewish science.

There was then in Toulouse a Jewish quarter of which the synagogue was the center. It was located between the south of the Place des Carmes and the Place Rouaix and between the Filatiers street and the Saint-Rémésy street . The Jewish cemetery was located near the Château Narbonnais, then when the king took possession of the place, at the end of the 13th century, it was relocated to a field bought by the Jews near the Porte de Montoulieu.

While they enjoyed a relatively good understanding with the local authorities, the Pope sent a letter to Count Raymond Vi, urging that Jews no longer participate in public life. From Alfonse de Poitiers, the brother of Saint-Louis, seizing Toulouse in 1249 until the expulsion of the Jews from France ordered by Philippe le Bel in 1306, their situation gradually deteriorated.

During the 14th century, some of the expelled Jews will be allowed to return and then expelled again. This on several occasions. A crusade of adolescents from Paris raged in the country in 1320, with devastating effects in the southwest.

Francisco Sanchez, born in a Jewish family in Portugal, studied in Bordeaux and Montpellier. He moved to Toulouse in 1581, where he practiced medicine. He became dean of the Faculty of Medicine in 1621 but was best known for his skeptical philosophical work: Quod nihil scitur (1580). A work published at the same time as the Essais de Montaigne, a philosopher also linked to Toulouse.

In the 17th century, when a group of Marranos attempted to settle in Toulouse, they were tried by an Inquisition tribunal in 1685. In the spirit of the emancipation granted by the French Revolution and Napoleon, the situation of the Jews improved in France in the 19th century. In the 1807 census, there were 87 Jews in Toulouse. Mainly traders from Avignon or working as a peddler.

Rabbi Léon Oury, originally from Alsace, was the first, in 1852, to officially practice in Toulouse for several centuries. Other Jewish personalities in Toulouse include Jassuda-David Musca, who in 1867 created a committee of the Alliance Israelite Universelle in Toulouse. But also Léon Cohn, the prefect of the city (from 1886 to 1894) and one of the founders of the labor exchange, the philosopher Frédéric Rauh and the poet Ephraïm Mikhaël, close to Bernard Lazare with whom he will write a play La Fiancée de Corinthe.

In 1887, there were only 350 Jews in Toulouse. Waves of migration from Alsace-Lorraine following the war of 1870 and between the wars in Eastern Europe and Turkey will increase this number. Among them, students from Poland and the Balkans attracted by the good study conditions at the University of Toulouse.

At the start of World War II, Toulouse welcomed refugees such as Léon Blum. Many Jews fleeing the German army ended up in the south and were interned in camps in the region, such as Gurs, Noé and Récébédou. Monsignor Saliège sent a letter of protest concerning the fate of the Jews which was read in all the churches of the diocese. In August 1942 the first deportations began to the camps in the East. The free zone was occupied from November and the deportations accelerated.

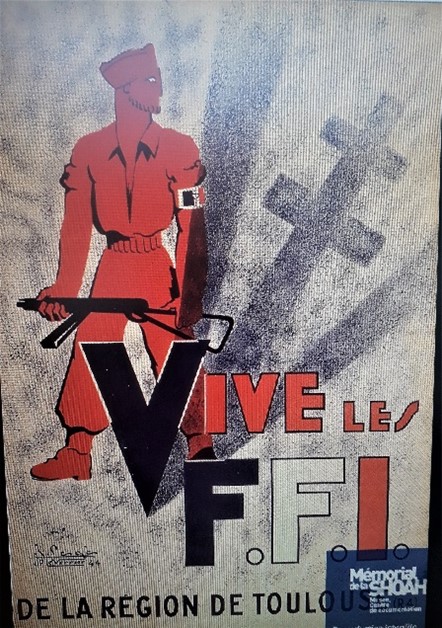

The Resistance is very active in Toulouse and Jews are joining its ranks in large numbers. Among the groups in place, the 35th FTP-MOI brigade which, under Marcel Langer, carried out numerous attacks. A monument at the Terre Cabade cemetery pays tribute to his courage, leadership and sacrifice. But also the Jewish Army, led by Abraham Polonski and Aaron-Lucien Lublin, the Israelites Scouts of France and the Jewish Combat Organization. The latter organized numerous convoy attacks and passages of combatants in the areas of struggle.

On July 17, 1944, several senior officials of the OJC, including Rabbi René Kapel, André Amar, César Chamay, Jacques Lazarus, Henri Pohoryles, Ernest Appenzeller and Maurice Loebenberg were trapped by the Gestapo. There were also women among the great figures of the Resistance. In particular Sarah-Ariane Fixman-Knout. While her husband took refuge in Switzerland with their children, she took up arms and was murdered on July 22, 1944.

Among the other figures of the Toulouse Resistance, Rabbi Moïse Cassorla and his successor at the Palaprat Synagogue , Rabbi Nathan Hosanski. This strong presence of Toulouse Jews in the Resistance was reflected after the war in the will of these fighters and survivors of the camps to rebuild Jewish life there.

In 1960, Toulouse had more than 3000 Jews. During this decade, the arrival of many Jews from North Africa allowed the community to grow, reaching 20,000 Jews in 1969. A relatively stable number in 2025, with more than 15,000 Jews in Toulouse.

The city of Toulouse now has around ten synagogues, in addition to that of Palaprat mentioned above. Among them, the Beth Habad , Chaaré Emeth and the Association of Liberal Jews of Toulouse .

The Espace du Judaïsme Toulouse is one of the largest community centres in Europe, co-chaired by the Consistoire and the FSJU. It is home to the Hebraïca cultural association, a synagogue, an oratory, language and art courses, a radio station and a cafeteria. Annual events include the Days of Jewish Culture and the Spring Festival of Israeli Cinema.

But Toulouse, like many places in France, has also been marked by a wave of anti-Semitism since the turn of the century. The murders of Jonathan Sandler, Gabriel Sandler, Arié Sandler and Myriam Monsonego at the Ozar Hatorah school in Toulouse and those committed in Toulouse and Montauban by the same terrorist against soldiers Imad Ibn Ziaten, Abel Chennouf and Mohamed Legouad deeply moved the nation in 2012. A plaque has been laid in memory of these victims in the Square Charles de Gaulle , which surrounds the Donjon du Capitole. The Monsonego-Sandler alley runs through the Jardin Michelet. And the Imad Ibn Ziaten, Abel Chennouf and Mohamed Legouad alleys surround the Caserne Niel garden.

Interview of Gilles Nacache (member of the CRIF Midi-Pyrénées’ steering committee), Yves Bounan (President of the ACIT) and Pierre Lasry (Secretary General of the Hebraica cultural assaciation).

Jguideeurope: From the great participation in the Resistance to the reconstruction of the post-war community, how do you explain the strong attachment of the Toulouse Jews to their city?

Gilles Nacache, Yves Bounan and Pierre Lasry: Toulouse Jews arrived in successive waves of immigration: Tsarist Russia, Turkey, Egypt, Germany, Poland, North Africa: from a few families at the start of the 19th century, we became one of the first communities in France and this mosaic of itineraries is undoubtedly the secret of our legendary cohesion and of the attachment that Toulouse Jews have for this somewhat Spanish-looking city, dynamic and rather young, with more than 100,000 students.

Toulouse was a bastion of the French and Jewish Resistance and the assassination of Marcel Langer, beheaded in Saint-Michel prison because he was a Jew, a foreigner and a Communist, is one of the outstanding episodes. Georges Cohen, one of the founders of the Jewish Army, the father of Monique Lise Cohen, an important figure who has just passed away, was also an example of the Jewish resistance in Toulouse.

Which place linked to Toulouse’s Jewish cultural heritage has particularly marked you?

The Palaprat synagogue is an emblematic place of Toulouse’s Jewish heritage. It was built in 1857 and it remains today the oldest synagogue, the one reserved for great patriotic ceremonies and official receptions. It has historically been the center of Jewish resistance in the south of Toulouse. It represents with its many wall plaques, a center of memory for more than a century for the regional Jewish community. A plaque in memory of Cardinal Saliège is also remarkable. The rabbinate of Toulouse extends its area of influence over 9 departments around Toulouse.

What educational and cultural approaches were put in place following the 2012 attacks?

A memorial ceremony takes place every March 19 at the Ohr Torah school, it is an opportunity to recall the events that took place there, often in the presence of a minister and sometimes a head of state. The educational approaches are less known to the public but they probably exist in several establishments and with certainty at the Ohr Torah school. Last year, an alley in a public garden was named after the victims in the presence of Nicolas Sarkozy and several ministers. A delegation of imams led by Marek Halter was also received at Ohr Torah, as well as many visitors from marks such as the Conference of American Association Presidents or the Prime Minister of Ukraine and the CEO of the El Al Company.

The Norman city is mainly known for its port, the second most important in France after Marseille. A port immortalized in the movie Le Quai des Brumes by Marcel Carné and Jacques Prévert, with Jean Gabin, Michèle Morgan, Pierre Brasseur and Michel Simon.

The community had existed since at least the 1920s, with the arrival of Tunisian Jews after the First World War. Previously there was a presence of Ashkenazi Jews who worked in Le Havre in the coffee and cotton trade and who largely resided in Paris.

Le Havre being nicknamed at the time the first port before the Americas, migrants therefore passed through the city to get there.

Some stayed behind, finding the living environment pleasant. For these same strategic reasons, Le Havre was a strategic hold for the German invaders who transformed the city into a naval base.

Léon Meyer, who was mayor from 1919 to 1940, adopted a policy of building affordable housing and increasing municipal social assistance services, which won him strong popular and worker support.

He also campaigned for equality between men and women. Removed from his functions by the Pétainist government, he was then deported and survived the camps.

There were 300 Jews in Le Havre at the dawn of World War II. The majority lived in the popular Notre-Dame district. The Jews had to flee and about fifteen were deported.

In all, 900 people are arrested in Normandy for their Judaism. 740 are deported. Meanwhile, the Resistance networks in Le Havre help British intelligence.

The synagogue on rue Victor Hugo has been attributed as war damage by the town hall. The old synagogue was in the district of Saint-François, near the beach and other areas bombed by the Allies before the D-Day landings.

The city of Le Havre was largely destroyed by these bombings carried out between 1942 and 1944, which was also the case for the synagogue and Christian places of worship, as well as institutional and cultural representations. Thousands of Le Havre died, caught between the two fires.

In 2017, around 20 volunteer high school students took part with their history and geography teachers in a major Holocaust mapping project in Le Havre. To retrace the persecutions but also to evoke the Jewish life of the time and to transmit this little known part of the history of their city.

In the 1950s, the community was given land on which there was a temporary caravan pending the granting of rights for the reconstruction of a synagogue.

A little later, a room was allocated which looked like a shed, transformed into a synagogue , rue Victor Hugo.

The North African Sephardim in the 1960s enabled the number of Jews to reach between nearly 220 families. In those post-war years, the community was chaired by Mr Bauer, owner of a large ready-to-wear store in the city center.

Rabbi Solomon Abikzer accomplished some important work to unify the Jewish community of Le Havre, Ashkenazim and Sephardim, especially in the ritual. For example, the rabbi printed a sidur where the two rituals were included, a sidur used for the Tishrei festivals.