The Jews in the capital of Italy are perhaps the oldest Romans of all. They have settled in the same ancient neighborhoods in the heart of the Eternal City for 2000 years, making their homes in the former ghetto, in Trastevere, and on both sides of the Tiber River where it is crossed by the Ponte Fabricio or Ponte Quattro Capi.

Not only one of the oldest communities of the peninsula, Roman Jewry also represents one of the most important, lively, and deeply rooted communities today, with its own dialect containing Hebrew words and particular culinary tradition. This 2000-year-old homeland, without equal with the exception of Israel, preserves numerous monuments dating from all periods, from the Jewish catacombs or the Ostia Antica Synagogue to the Grand Temple constructed at the beginning of the twentieth century on the location of the former ghetto.

A visit to Jewish Rome merits at least five days. In this Christian capital, the rich remains of Jewish history proper are augmented by many things that attest to papal policy regarding the Jews. Some for the better and most for the worst, these physical records conditioned Jewish life in Rome -if not in the west as a whole.

Certain Jewish dishes still make up part of Roman gastronomy and appear on the menus of numerous restaurants. A case in point is carcioffi all giudea (artichokes Jewish style): the artichoke is fried in oil until the small leaves are marvelously crispy. The traditional cuisine of the Eternal City’s lower classes is based on inexpensive ingredients, lower quality cuts of meat, and lots of vegetables. These characteristics are more markedly noticeable in dishes typical of the Jews in the capital, confined for three centuries in the ghetto.

Many recipes, notably for fish, are agro-dolci (bitter sweet) with sugar, vinegar, pine nuts, and raisins, representing a tradition dating back to the Roman period. Fried dishes make up the lion’s share of typical Roman cooking; aside from the artichokes already mentioned, these include fiori di zucchine (fried zucchini blossoms stuffed with mozzarella and anchovies) or the fritto di baccalà (salt cod croquette). The pasta and soup recipes are hearty, stick-to-the-ribs dishes like the traditional ceci e pennerelli (chickpeas and leftover meat morsels) simmered on a low fire for three hours.

The former ghetto

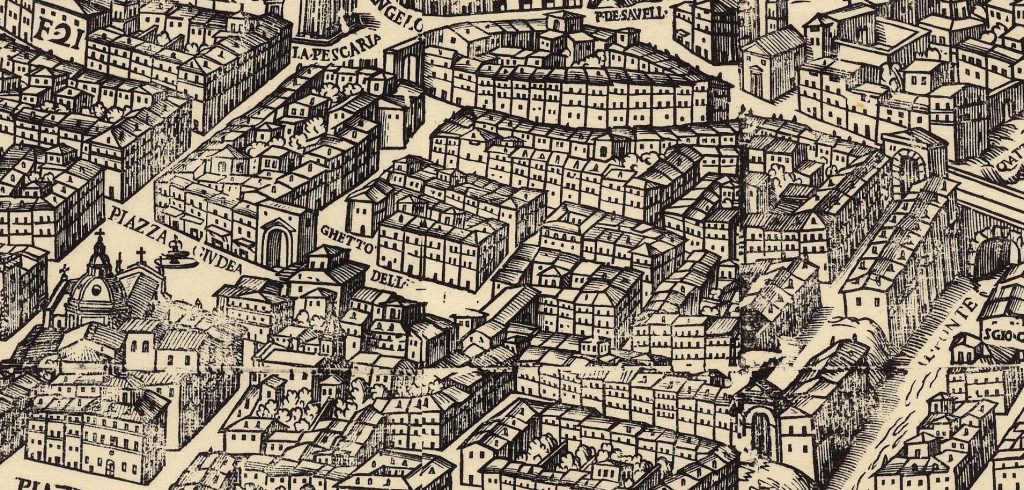

The quarter where the Jews were forced to reside for three centuries until 1870 is at the center of the Italian capital, between the Largo Argentina, the Capitoline, and the Tiber. Almost nothing remains of the stifling, cramped streets of the old ghetto, which was destroyed, sanitized, and reconstructed in the first years of the twentieth century. The neighboring narrow streets, such as Via della Reginella or the beginning of Via Sant’Angelo in Pescheria, give an idea of what the lives of the Jews in the city were like for three hundred years.

Portico d’Ottavia, constructed by Cecilius Metella in 146 B.C.E. remains one of the symbolic places of the former Roman ghetto. The remains of the fluted columns rise from among the enormous paving stones surrounding the large Temple of Juno on Via del Portico d’Ottavia.

Restaurants set up their sidewalk tables from which the regulars take in the fresh air. This portal marks one of the five former entrances to this forced residential quarter. It was customarily barred at night with a great iron chain. The Piazza delle Cinque Scole surrounds a fountain by Giacomo della Porta (erected in 1591, rebuilt in 1930) commemorating the five synagogues of the former ghetto (Catalana, Castigliana, Tempio, Siciliana, and Nova).

These were all located in a single building that has since vanished but which was located on the present-day square at number 37. The current building is constructed on the site of the former Platea Judea, or “grand square”, divided into two halves by the ghetto wall, which was the intersection of two ancient thoroughfares of the Jewish quarter, Via Pescaria and Via Rua.

It was in the Platea Judea, at once inside and outside the ghetto, that the economic activities permitted to the Jews of Rome took place. These activities included trade in old clothing, used goods, and some artisanal work. In periods of tolerance these stalls were permitted to open on Sunday and the villagers who had come to the city and did not want to lose a day would come her to make their purchases.

The Piazza delle Cinque Scole, with its many shops, remains the heart of the quarter. Be sure not to miss a pasticceria called Boccione, which sells cakes typical of the Roman-Jewish tradition such as its extraordinary cheesecake made from ricotta. Menorah , a nearby bookstore, is well stocked with both old and new books on Judaism in Italian, French and English.

Heading back up this narrow, shadowy street toward the Piazza Mattei, with its magnificent “tortoise” fountain constructed in 1581-84, it is possible to get an idea of what the ghetto was like back in those ancient times. The blocks of buildings situated between Via Reginella and Via Sant’Ambrogio became part of the Jewish quarter when Pope Leon XII designed to enlarge it a little in 1823.

Completely on the other side of the former Jewish quarter, and heading in the direction of the Tiber and the Grand Temple, stands the small church of San Gregorio all Divina Pietà, constructed in the eighteenth century opposite one of the ghetto gates. Its facade features an inscription in Latin and Hebrew citing the prophet Isaiah speaking “to those rebellious people who act according to ideas in a way which isn’t good, to those people who continually provoke my anger”. This was one of the places where each Sunday, representatives of the Jewish community were obliged to listen to the Catholic Mass.

The Grand Temple

The zinc dome of the Grand Temple rises 151 feet above the street and can be seen from anywhere in Rome among the other baroque domes of the many churches in the Eternal City.

It is easily recognized by its square shape. Constructed between 1901 and 1904, hardly more than thirty years after the closing of the ghetto, the Grand Temple celebrates the Italian Jews and their extraordinary integration. The style of the Temple is oriental, though some have ironically described it as neo-Babylonian.

“Between the Capitoline and the Janiculum, between the monument to Victor Emmanuel and that of Garibaldi, the two great masters of our Italy, stands this majestic temple surrounded by the pure, free sunshine that signals liberty ad love”, declared Angelo Sereni, president of the Jewish community, whose perhaps florid rhetoric on the occasion of the building’s opening nevertheless expressed the state of mind of his fellow believers at the time.

Surrounded by a lovely garden with palm trees, the building was constructed on a large, 32000 square foot piece of land made available by the demolition of the former ghetto, which had been completely razed shorty before and replaced with the large liberty-style buildings. Since at the time there were no licensed Jewish architects, its two designers, Vincenzo Costa and Osvaldo Armani, were non-Jews.

The facade is adorned wit palms and has three large windows. Near its top, the building features a tympanum decorated with the Tablets of the Law, above which stands a seven-branched menorah. The interior of the main hall is sumptuous, with marble columns in an oriental style. The aron, above the steps of a platform at the end of the nave, evokes the altar of a church, like many of the synagogues constructed just after the Jews’ emancipation. Abundant light pours in through the large liberty-style windows. The interior of the large dome is decorated with oriental-style paintings (palms and starry sky) by Annibale Brugnoli and Domenico Bruschi. In the halls of the Grand Temple many of the objects historically used in the five synagogues of the former ghetto have been assembled and are on display.

Especially noteworthy are the magnificent marble-columned aronot from the Siciliana Synagogue of 1586 and that of the Castigliana Synagogue of 1642. The Spanish Temple, occupying since 1932 a large part of the Grand Temple, perpetuates the tradition of Jews who came from the Iberian Peninsula, while the majority of the services are now in Italian. The hall with its aron facing the tevah evokes the atmosphere of the former Roman synagogue that has since disappeared. The Jewish Museum occupies one of the wings of the Grand Temple. Numerous silver religious objects, circumcision chairs, candelabras, fabrics, and manuscripts, including three volumes of poems in Judeo-Roman by Crescenzo del Monte (1868-1935), are on display in two vast rooms.

Tiber Island and Trastevere

The only island in the Tiber River as it snakes through Rome, Tiber Island was consecrated by the ancient Romans to Aesculapius, the god of medicine. Since the Middle Ages, it has been the site of the hospices or hospitals. The island links the Jewish quarter on either side of the river; thus in the eleventh century both the Ponte Fabricio and the Ponte Quattro Capi were alternately called the Pons Judeorum. In 1870 the confraternities of the former ghetto settled here in order to create aid organizations for the newly emancipated Jews. One one side of the island’s central street facing upstream stand the Israelite hospital and the Panzieri-Fatucci oratory, called the Tempio dei Giovanni. The nineteenth century wooden aron of the oratory originally came from the five synagogues. The brightly colored stained-glass windows representing Jewish holidays were completed in 1988.

One the other side of the river is the Trastevere (literally, “beyond the Tevere [Tiber]”) district. In his travel journals during a trip to Italy in the twelfth century, Benjamin de Tudela, a Jew from Navarre, recounts that numerous Jews lived here during imperial Rome and during the medieval period. Traces of this past that survived the imprisonment of the Jews in the ghetto in 1555 are rare. At 14 Vicolo de l’Atleta stands a small brick building with two arches. A Hebrew inscription on a column of the loggia and a well in the courtyard indicate that it probably functioned as a synagogue in the Middle Ages.

The former cemetery was in the area of Porta Portese, where the flea market is held every Sunday. After 1870, a large part of Roman-Jewish life once again moved to the Trastevere district, where today the majority of the community’s institutions are concentrated, including Il Pittigliani , the former Jewish orphanage, which has been transformed into a cultural center with a kosher snack bar and library possessing numerous documents on Jewish life in the capital.

The headquarters if the Union of the Italian Hebrew Communities is located on the other side of Viale Trastevere, the large avenue dividing the district. It includes a documentation center on Jewish heritage and, a little further along, at number 14 and 12, the Hebrew day care and primary school respectively. The Roman poets and Folklore Museum merits a brief visit to see the three paintings by Ettore Roesler Franz (1845-1907) depicting scenes of everyday life in the ghetto.

The Forum

The center of power under the republic and later the empire was the Fori Imperiali, located between the Piazza Venezia and the Coliseum. In the Forum are also located tow monuments directly tied to Jewish history.

The Arch of Titus celebrates the emperor’s victory and that of his father, Vespasian, over the Jewish revolt in 70 C.E. Constructed after Titus’s death in 81 C.E., the interior of the arch contains two large bas-reliefs illustrating the triumphal procession loaded with booty taken from the Temple of Solomon, including notably a seven-armed candelabra and silver horns. A symbol of defeat and the Diaspora, the Arch of Titus has naturally been an humiliation for Roman Jews. When the Nation of Israel was proclaimed in 1948, “they paraded under the arch in the opposite direction of Titus’s triumphal march”, relate Bice Migliau and Michaela Procaccia in their book on travel in Jewish Rome and Latium.

At the other end of the Forum, heading toward the Capitoline, stands the ancient Mammertine prison with its lugubrious underground cells where the enemies of Rome were imprisoned and executed after being led in shame through the city behind the chariot of the victor. A plaque recalls this was the fate one such prisoner, Simon Ghiora, a defender of Jerusale; in 70 C.E.

Leaving the Forum by the main entrance and going back up Via Cavour, you will find the Basilica San Pietro in Vincoli at the top of a large staircase. Originally constructed to hold the chains of St. Peter in the fifth century, it was altered at the beginning of the sixteenth century by Cardinal della Rovere, the future Pope Julius II, to be a funerary monument. Here is located the celebrated statue of Moses by Michelangelo. Powerful and admonishing, the prophet, seated holding the Tablets of the Law, is represented at the moment when he has just descended from Mount Sinai and sees the idolatry of his people.

The Jewish catacombs

The catacombs were constructed in the first years of the Christian era by Jews influenced by the Roman custom of entombing the dead in deep stone chambers. Six sites have ben discovered around Rome. The first, Monteverdi, close to the Janiculum, was discovered in the seventeenth century. Only two Jewish catacombs are open today, that of the Villa Tortonia on Via Nomentana and that of Vigna Randanini, close to Via Appia Antica. The arrangement of the catacombs in galleries scarcely 3 ft. high x 7-9 ft. differs little from the Christian catacombs.

Considered as religiously impure place, the catacombs were not used by Jews for liturgical celebrations other than the burials”, writes Attilio Milano in his History of the Italian Jews. The walls are decorated with inscriptions, most often in Greek, and with such symbols as the menorah, the Scrolls of the Law, the shofroth, and palm branches.

Two rooms of the Vigna Randanini galleries are decorated with secular motifs (eagles, peacocks, griffins) and on the ceilings, a winged Victory and a personification of Fortune are represented. Some analysts interpret these figures as a result of the influence of the surrounding society; other emphasize that these catacombs were probably first pagan tombs and only later integrated into the Jewish burial complex.

Memorial to the Adreatine Mass Graves

On via Adreatina, just beyond its intersection with Via delle Sette Chiese and near Via Appia Antica, stands the Memorial to the Adreatine Mass Graves. On 24 March 1944 the SS troops of Herbert Kappler massacred on this spot 335 hostages, 70 of which were Jews, This mass execution was in retribution for the thirty-two German soldiers who were victims of the Resistance. The monument, The Martyrs, was sculpted in 1950 by Francesco Coccia. A cross and a Star of David rise above the wall of the burial plot.

Ostia

The excavations at Ostia (Ostia Antica), the great port of imperial Rome, bear impressive witness to Roman urbanism and deserve a visit to see the synagogue discovered there in 1962 when ground was broken for a new highway to Fiumicino Airport. The synagogue borders the northeastern edge of the archaeological zone, just beyond the Porta Marina. Its initial construction dates back to the first half of the first century C.E. and it was rebuilt several times until the fourth century. The synagogue complex includes a prayer hall, study room, and an oven for baking unleavened bread. There are three entrances: one for men, one for women, and the entrance to the mikvah, whose remains are still visible. One can still see the aron flanked by two columns whose capitals support the remains of a frieze decorated with menorot, palm branches and shofroth. There is a small podium at the opposite end of the room that served as the bimah.

The Archaeological Museum features several lovely lamps decorated with seven-arm candelabras.

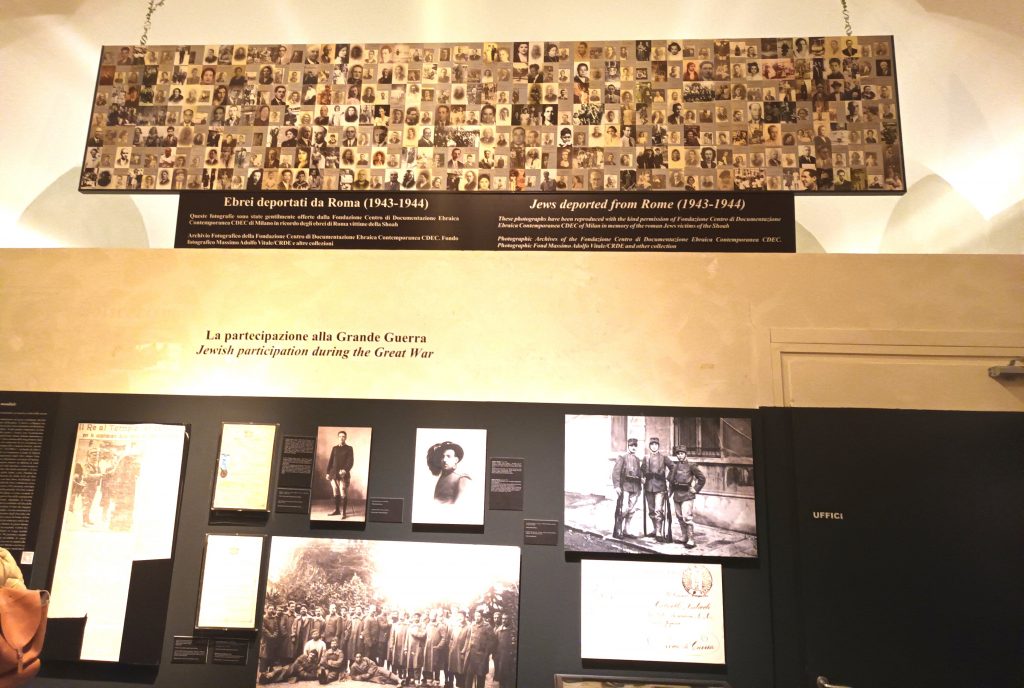

Faced with rising anti-Semitism, Pope Leo XIV called in September 2025 for joint efforts to promote interfaith dialogue. As in many other European cities, Rome has seen violent outbreaks of anti-Semitism following the importation and exploitation of the conflict between Israel and Hamas in the wake of the 7 October pogrom. These included acts of vandalism against the synagogue in the Monteverde district and the plaque commemorating Stefano Gaj Taché, a two-year-old baby murdered by Palestinian terrorists in 1982 during the attack on the Great Synagogue of Rome.

In an effort not to give in to the rise in anti-Semitism since 2023 and to continue sharing Italy’s Jewish cultural heritage, numerous events have been organised in recent years as part of European Jewish Culture Days. These included conferences, exhibitions, book presentations and guided tours of the Jewish Museum of Rome, the Shoah Museum and the synagogue of Ostia Antica in Rome in September 2025.