A rich and influential Jewish community lived in Trieste, a large port city of the Austro-Hungarian Empire that became Italian only after the First World War. During the nineteenth century and the first decades of the twentieth century, this community had a profound impact of the economic and cultural life of the city. Enclosed in the ghetto in 1696, the Jews enjoyed a de facto emancipation in 1782 through the Toleranzpatent of Emperor Joseph II.

Consequently, the history of Trieste’s Judaism mingles with that of Austria, especially Viennese Judaism, and shares all its splendor. This is still in evidence today by the many palaces of large bourgeois families in the city, such as the Morpurgo de Nilma, the Hierschel de Minerbi, the Treves, the Vivantes, and others. This large commercial port was the empire’s only access to the sea. It was also an intellectual capital, where the Jews, before and after 1918, had important roles as writers (Italo Svevo, Umberto Saba, the publisher Roberto Bazlen, Giorgio Voghera and as painters (Isodoro Grünhut, Gino Parin, Vittorio Bolaffio, Arturo Nathan, Giorgio Settala and Arturo Rietti). The presence of Edoardo Weiss (1889-1970) in the city made it the cradle of Italian psychoanalysis.

During the the first half of the Twentieth century, Trieste was also one of the ports of departure for Jews emigrating to Palestine. The Shoah was deeply felt by the Jews of this city. Nowadays, the Jewish community counts one tenth of what it was before the war.

The Grand Synagogue

Constructed in 1912 by a community that wanted to show its wealth and power, the synagogue of Trieste represents architecturally one of the most significant edifices of emancipated Judaism at the end of the nineteenth century. Spacious, elegant, and free of any kitsch, the synagogue was designed by the architects Ruggero and Arduino Berlam without any regard for expense.

The decorations, in part inspired by those of certain Christian edifices of the Near East (i.e., Syrian), also show – in the mosaics, the starry dome, and the splendid luminosity of the interior – the influences of the styles fashionable in Vienna at the beginning of the twentieth century.

Jewish Trieste

The Jewish cemetery is at 4 via della Pace since 1843. The old one was on the hill of San Giusto (mid 15th century – mid 19th century), behind via del Monte, the steep street in which are now located the Jewish school and the Carlo and Vera Wagner Museum. This was formerly the location of an Ashkenazic oratory where German, Czech, and Polish refugees prayed before emigrating to Palestine between the wars. The building hosted the Jewish Agency for Israel, which helped thousands of people escape from Russian and then Nazi anti-Semitism. In fact, Jews called the port city of Trieste the “Door of Zion”. The oratory is now part of the Museum. Ornaments and gold objects on display here are in some cases quite antique; many come from Bohemia and Germany as well as from Italy.

Narrow streets such as Via del Ponte, near the Piazza della Borsa give an idea of what this former Jewish quarter might have been like a century ago, when it was inhabited by poor Jews and still had four synagogues, whose discreet facades hid richly decorated interiors. The buildings and synagogues of the early Ghetto were totally razed in the 1930s to the great joy of the heads of the Jewish community of Trieste, which had no desire to see the remains of their miserable past. Many of the synagogue’s furnishings are now in Israel.

The Caffè San Marco near the Grand Synagogue, a favorite haunt of Trieste’s intelligentsia, remains one of the most memorable places in the city. Italo Svevo frequented Caffè San Marco, as did a number of artists and writers both Jewish and non-Jewish. The traditions continues today with authors such as Claudio Magris, who dedicated the magnificent pages Microcosmes (Paris: Gallimard, 1998) to the café. The turn-of-century Viennese Succession-style interior is remarkable -as are the coffee and food.

Renowned throughout the city for the quality of its products – not to mention its interior decor – the celebrated pastry shop La Bomboniera was also, until the 1930s, a kosher pasticceria whose Purim cakes made between February and March delighted Trieste’s residents, Jewish and non-Jewish alike.

Morpurgo de Nilma Civic Museum

Installed in the palace he had built in 1875, the Morpurgo de Nilma Civic Museum is named after Carlo Marco Morpurgo, declared a valiant knight of the empire for his achievements. The palace suggests what daily life was like for a large Jewish family of Trieste.

The private apartments are on the third floor and include a magnificent Louis XVI-style music room, a large azure reception hall decorated in the Venetian style, and a pink salon, among others. Other palaces once belonging to great Jewish families such as the Hierschel de Minerbi at 9 Corso Italia, or the Vivante at 4 Piazza Benco are located in the neighboring streets and have been transformed into apartment buildings or offices.

Risiera of San Saba

The Nazis established the only Italian concentration camp with a crematorium, Risiera of San Saba , in the buildings of a former rice-processing factory. It was a camp used for the detention and elimination of Jews, hostages, partisans and political prisoners. For Jewish prisoners, it was mainly a transit site on the way to the extermination camps. Between October 1943 and March 1945, 22 convoys of Jews were deported from Risiera. In total, more than 1000 Jews were deported from Trieste and about 30 were killed in the Risiera.

The site was transformed into a memorial in 1965. Ten years later, it became a Civic museum designed by architect Romano Boico and it has been recently renewed.

In 2025, a powerful gesture by the people of Trieste saved a landmark of local Jewish culture: the Umberto Saba antique bookshop . Opened in 1919 by the Italian poet of the same name, it looked set to close in 2023.

Born in 1883 and related by his mother to the poet Samuel David Luzzatto, he used the money from a family inheritance to open the bookshop, whose walls belonged to the Jewish community of Trieste, while continuing to write. He sold rare and antique books on literature, philosophy, history, religion and boats. In 1924, he hired Carlo Cerne, a young man abandoned by his parents and living in very precarious conditions, whose vocation for this profession he identified.

Together they formed a formidable team, expanding the bookshop. In those dark years, Umberto Saba spoke out and wrote against Mussolini. When the Nazis invaded Trieste in 1943, he had to flee, hidden by friends. Severely scarred by the war, he gradually handed over management to Carlo Cerne, who died in 1957. Cerne hired his son Mario, who took over the bookshop in 1981, after Carlo’s death. Mario ran the bookshop until he fell very ill in 2023, highlighting in particular the work and courage of Umberto Saba.

The building still belonged to the Jewish community of Trieste when the lawyer Paolo Volli, whose offices were located in the same building as the bookshop, organised a fund-raising campaign to save it. This emblematic place motivated the commitment of the literary-minded population of Trieste – after all, James Joyce wrote his masterpiece Ulysses there. It was also a personal story for Volli, Umberto Saba having saved his own grandfather’s book collection by hiding it just before the Nazis invaded.

On 28 January 2025, the Umberto Saba bookshop celebrated its reopening, which included a number of areas, including a museum in tribute to its founder, a reading room and a room hosting literary events. This date marked the one-year anniversary of Mario Cerne’s death. His daughter Ada, who lives in London, took an active part in the project and was officially presented with the keys to the site by the Jewish community at a ceremony. She hired a director to continue this wonderful literary adventure.

Interview with Annalisa Di Fant, curator at the Museum of the Jewish Community of Trieste Carlo e Vera Wagner

Jguideeurope : Can you tell us how the Museum was created?

Annalisa Di Fant : The “Carlo and Vera Wagner” Museum opened in 1993, the brainchild of Mario Stock, at that time president of the Jewish Community, and of Gianna, daughter of Carlo and Vera Wagner, and her husband, Claudio de Polo Saibanti. The set-up was devised by the architect Ennio Cervi, with the scholarly advice of Luisa Crusvar, Silvio Cusin, Ariel Haddad and Livio Vasieri.

The perfect location was found in via del Monte 5-7: a building of particular historical significance to the Community, one which has been declared a site of national interest. Since the end of the eighteenth century to the late nineteenth century, Via del Monte 5-7 had been a Jewish hospital. From the beginning of the twentieth century, it was used to host the thousands of refugees fleeing Tsarist anti-Semitism and, later, Nazism. These refugees left from the port of Trieste to travel to British Palestine or the Americas. The building also housed the Jewish Agency, which assisted Jewish emigrants leaving for Eretz Israel. In recognition of its role during the two World Wars, the city has earned the epithet of Shaar Zion, Gateway to Zion.

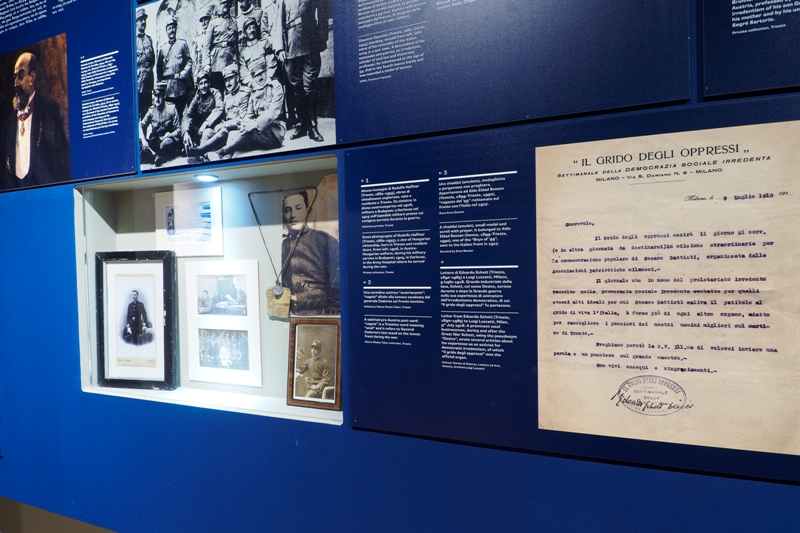

In 2014–15, the Jewish Community of Trieste undertook a complete rearrangement of the permanent exhibition. The new museum itinerary and texts were devised by Annalisa Di Fant, under the supervision of Tullia Catalan and with the assistance of the scientific committee, namely Stefano Fattorini, Ariel Haddad, Mauro Tabor, and Livio Vasieri. There were two main objectives: to appreciate the Museum’s wealth of offerings, which in terms of both quality and quantity are among the most important in Italy and which represent a unique testimony of Jewish life in Friuli Venezia Giulia; to make the exhibition as accessible as possible for visitors from Italy and further afield – thanks to English versions of all materials – with the particular aim of engaging school groups.

On 14 September 2014, to mark the European Day of Jewish Culture, the first restored part of the Museum was inaugurated: the section dedicated to culture, which is located on the first floor of Via del Monte 7, where there is also the conference space. The project was managed by Massimiliano Schiozzi and Cristina Vendramin (Comunicarte, Trieste). On 29 March 2015 the restoration was completed, and the ground floor spaces, accessible from Via del Monte 5, were opened, with sections dedicated to the spirituality, traditions and history of the Jewish Community of Trieste, the Holocaust, and the links with Eretz Israel. The project was managed by Giovanni Damiani and Matteo Bartoli (Fresco, Trieste). In 2017, there was a further expansion: the second floor of Via del Monte 7 was transformed into a space for temporary exhibitions. This project was carried out by Giovanni Damiani.

Are there educational projects proposed by the Museum and how is the city of Trieste participating in the sharing of Jewish culture ?

The Museum is particularly dedicated to its links with schools: from teacher training, and the annual organisation of refresher courses, to the warm welcome we extend to school groups of every level.

Since 2017, the Museum, along with the Jewish Community of Trieste, has an ongoing arrangement with the Dipartimento di Studi Umanistici at the Università di Trieste, where Professor Tullia Catalan – the Museum’s academic advisor – works as a lecturer in Jewish History. Thanks to this accord, there are internships of 75 or 150 hours available to those who have taken the exam in Jewish History.

The Museum also has strong and fruitful collaborative links with the Liceo linguistico F. Petrarca and the Istituto Tecnico Statale “G. Deledda – M. Fabiani”, with whom work experience projects have been organised, allowing students from these schools to be actively involved with the Museum several activities.

Can you share a personal anecdote about an emotional encounter with a visitor or researcher during a previous event?

Very recently, the Museum has been visited by an Israeli citizen, a lovely, brilliant gentleman 93 years old! He has very vivid memories of Trieste and in a picture reproduced in one of the Museum’s panels he has recognized his brother, portrayed among others during a Purim at the Jewish School of Trieste, year 1931. They were both born in Trieste to a family that arrived here from Poland after the First World War, being the father called to practice as a shokhet by the Trieste Jewish community. The family quickly entered the local Jewish nucleus and the children attended the community school.

Unfortunately, at the end of the summer of 1938, the whole family, then made up of eight people, was affected by the racial law, which obliged all foreign or stateless Jewish citizens to leave the Kingdom of Italy by March 1939. Thus, after several failed attempts and helped by Misrad who was based in the building where the Museum is located, the Garncarz left with a Lloyd ship on March 29, 1939 for Tangier. And they remained there for four long years, before landing in Haifa in 1943. They had finally found the place to take new roots. But they never forgot Trieste…

Very often, people who fled Trieste because of fascist racial laws come back to see the city and come to visit us. Also, many descendants of the refugees hosted here in the first half of the Twentieth Century come to visit the Museum. These are always very moving encounters and often they enlarge our archives, by donating documents and pictures of those times.