The Jewish Museum Berlin is very active in the sharing of Jewish culture, and tackles difficult issues, among them recently the Jewish perspectives concerning the war in Ukraine and the changes occurred after the reunification of Germany. Here’s an interview with its director, Hetty Berg.

Jguideeurope: Can you give us some details about the upcoming exhibition devoted to Jews in the GDR?

Hetty Berg: The Jewish Museum Berlin (JMB) will show “Another Country. Jewish in the GDR” from September 8, 2023, the first major exhibition on Jewish experiences in the GDR. With this exhibition, the JMB is shedding light on a part of German history – from the post-war period to the present day – that until now has tended to be overshadowed by other experiences and narratives.

Personal objects from contemporary witnesses and their descendants, as well as interviews with Jews telling their stories, reveal a variety of individual perspectives. They convey sometimes contradictory experiences, which, especially in the case of questions about Jewish identity, move in the field of tension between attribution and self-image. The interviewees provide insight into historical developments, they remember, comment on socio-political conflicts or raise questions related to the exhibition objects. The interviews were conducted by documentary filmmaker Yael Reuveny as part of the Michael W. Blumenthal Fellowship specifically for the project; in eight film projections, the director uses images from today to explore a country that no longer exists in this form, but which has left clear traces in the present.

The cultural-historical exhibition explores her subject area in a documentary research journey and links it with visual art, film and literature, with multi-layered biographies and with extraordinary exhibits. In this way, insights are gained into the lives of Jews who fled Germany before the Nazis and returned to the Soviet occupation zone after 1945, surviving concentration camps or in hiding. After the experience of the Shoah, many of them hoped to build a free, anti-fascist state with the GDR. Jewish life in eight communities – in East Berlin, Dresden, Leipzig, Magdeburg, Erfurt, Schwerin, Halle and Chemnitz or Karl-Marx-Stadt – as well as nodal points of Jewish history in East Germany – such as the flight to the West in 1952/53 or the reactions to the Six-Day War in 1967 – are brought into focus as everyday and social history.

At the beginning of 2022, the JMB had launched a call for collections for the exhibition: With this and the cinematic portraits created in the course of the exhibition, the JMB is expanding its collection on the topic of “Jewish in the GDR.” The exhibition adds an important aspect to the current East-West discourse and consolidates the position of the JMB as a central platform for Jewish life and history throughout Germany.

The spectrum of the accompanying program ranges from a concert by a famous band to an academic conference. The exhibition itself also becomes a venue for events: readings, artist talks, performances – every Tuesday (with a few exceptions), guests in the exhibition give personal insights into their experiences, their family stories and their preoccupation with Jewish life in the GDR.

Do you see an evolution in the perception of Judaism in East Germany since the reunification?

This is a very complex question – and there is no simple answer, because of the many different perspectives. In any case, I would avoid the term “evolution” and prefer to talk about the specific discourses at a specific time, or specific positions. E.g., Germany celebrated the year 2021 with a lot of different events at different places, because 2021 marks 1700 years that Jews have lived in what is now the modern German state. But this anniversary does not seem to me to be a point of an evolution, not even an evolution with interruptions or jumps.

The reunification was a moment of profound disruption at the individual and societal level for everybody who lived in East Germany, also for the Jews, and for many people in West Germany, too. It turned into a moment, in which many aspects of their lives were renegotiated, including the notions of Jewishness. The East German state, the East German congregations, West German Jewish institutions, and East German individuals, who identified as Jewish, struggled over the definition of Jewishness in the postwar era. In 1986, with the creation of the Jewish community group “Wir für uns” (We for Ourselves) and its successor organization, the Jewish Cultural Association, the foundation for a pluralistic understanding of Jewish identity and Jewish culture had been laid. The most significant shift came with the dissolution of the Soviet Union in late 1991. Following the opening of East-West and Soviet borders, almost 220,000 Jews from the Soviet Union immigrated to a newly reunified Germany and were given refugee status. All of a sudden, new communities formed and older ones grew; community centers, schools and synagogues were built. The immigration saved the stagnating community from demographic collapse, but their integration also posed challenges, since most of the newcomers were much more secular than the local traditional communities. The negotiations about Judaism and the definition of “Jewishness” went on, still continue and turn to new – or old – aspects.

The Museum has been involved in programs related to the war in Ukraine. How was it perceived by the public?

The JMB, in cooperation with the “Federal Agency for Civic Education” and OFEK, a specialized counseling center for anti-Semitic incidents and acts of violence, invited the public to the discussion series “Ukraine in Context. Jewish perspectives on Ukraine, Present and Past”. The series of talks provides insights into the country’s multi-layered present against the backdrop of its history. Using the cities of Kharkiv, Chernivtsi, Odesa, Dnipro and Lviv, Ukrainian artists and scholars spoke about life and survival during the war, multiple affiliations, competing memories, identities, images of cities and history. The series began in October 2022 and the tentatively last event took place on May 8, 2023. All events are still available on our website.

The conversations on the panels were intense from a political and emotional perspective. Personal experiences of the war mixed with a historical view of Ukraine. The conversations also took on a special intensity with feeds from the war zone. The male participants were generally not allowed to leave Ukraine and had to be zoomed in.

We had about 150 guests per event. Many of the guests were originally from Ukraine – from the cities that were discussed on the panels. The panelists are grateful that we give them a voice here in Berlin. In this respect, this series was unusual in the explicit coming together of personal fates with scholarly and artistic perspectives on Ukraine – both on the panels and in the auditorium.

Can you present us some objects recently acquired by the Museum?

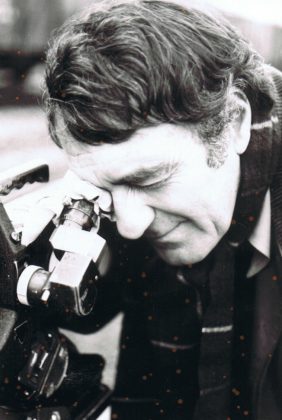

I only will mention three of them. First, the worldwide most famous is Claude Lanzmann’s audio archive for his film “Shoah” (France, 1985). In May 2023, the archive, along with the original 16mm and the restored 35mm film footage, was inscribed into the UNESCO register of the world’s documentary heritage, “Memory of the World.” The films are owned by the French company Les Films ALEPH. With this distinction, the JMB has for the first time become home to UNESCO-recognized world cultural heritage. Being able to preserve this extensive, as yet unpublished audio archive – created in the context of Lanzmann’s monumental cinematic work “Shoah” – here in Berlin is both a great privilege and a special obligation. For the past year, the audio recordings have enriched our collection with their unique perspective: Lanzmann’s documentary took an entirely new artistic approach and laid the methodological groundwork for oral history. The UNESCO distinction motivates us even more than before to explore the content of these holdings, open them up for research, and make them accessible online. The audio archive was donated to the JMB in late 2021 by Dominique Lanzmann. The recordings are stored on ordinary music cassettes. Upon receiving the gift, the JMB began digitizing the 200 hours of recordings in order to preserve them and make them accessible for the future.

The audio archive consists of audio recordings made by the journalist and filmmaker Claude Lanzmann (1925–2018), the grandson of Jewish immigrants from Eastern Europe, along with two of his colleagues, while they were researching “Shoah” in the years before filming began. The tapes document conversations with very different contemporary eyewitnesses: survivors of the ghettos and concentration camps, resistance fighters, historians, clerics, intellectuals, politicians, and perpetrators.

The film ”Shoah” was a watershed in perceptions of the Holocaust. Without seeming to lecture, the film is an instructive work supplying verified historical information, which it has anchored in the memory of an audience across the world. Lanzmann worked on the documentary for twelve years. Nine hours and 26 minutes long, it does not include a single archival image. The fact that the last witnesses to the Holocaust will soon have passed away further intensifies the great significance of the research and audio documentation that Lanzmann carried out.

Second, in 2022, Giora Feidman, just after he had given a wonderful concert with it in the garden of the museum, at the opening event of our “Summer of Culture”, donated one of his clarinets to the core exhibition.

Third, in 2021, the Jewish Museum Berlin acquired the first modern Hanukkah menorah, made in 1924 by Ludwig Wolpert. His creation broke with the stylistic conventions that had governed Judaica until then and ushered in a change of form and style that influenced and shaped the artistic designs of generations to come. The menorah is made of patinated cast brass and stands 34 cm tall and 38 cm wide.

Ever since opening twenty years ago, the Jewish Museum Berlin has specialized in collecting Jewish ceremonial objects from Germany dating to the late nineteenth and early twentieth century. We want to document the stylistic change that took place during this era. Only a very small number of Jewish ceremonial objects made by artists in Germany during the 1920s still exist today. Wolpert’s Hanukkah menorah is a prime example of this decisive period and Modernism’s creative awakening, and it fills a gap in the museum’s collection.

Could you share an emotional encounter you had with a visitor or a participant in one of your programs?

I remember an encounter with Micha Odenheimer, I know him from Israel for over 30 years. He came to the JMb to visit me as the new director – and told me, that in our new core exhibition there is a home movie from his family from the 1930’s.