Archaeologists have recently unearthed traces of a Jewish presence in Salona (Solin), capital of Roman Dalmatia and sister city to Split, that dates as far back as the first centuries C.E. Salona was destroyed in the seventh century, and its survivors, some of whom were Jewish, took refuge behind the solid walls of Emperor Diocletian’s palace, the origin of present-day Split.

Substantial evidence suggests that a synagogue was soon built in the southern section of the new city. In fact, until the sixteenth century, this section of the city was called “The Synagogue” by its inhabitants. Traces of it disappears during the Middle Ages, as Dalmatia’s Jewish communities are rarely mentioned in surviving texts, but when they are referred to as Zueca, a term used to designate areas occupied by tanners and dyers.

With the arrival of Jews from Spain and Portugal in the sixteenth century, Judaism in the region began expanding rapidly. One Spanish Jew, Daniel Rodriga (a name derived from the Spanish “Rodriguez”) played an essential part in the city’s evolution. He set in motion a number of development projects, including a lazareth (infirmary), and managed to convince his contemporaries to favor the land route across the mountains, which was far safer than navigating south of Split toward Turkey and the rest of Asia. His talents were recognized by the Republic of Venice, which in turn sought to raise the status of the city’s Jewish community. Jews were even allowed to engage in the food industry, which was forbidden everywhere else in Europe at the time.

Although Split’s Jews throughout the ages made up only 2 to 3% of the local population, they did not hesitate to prove their loyalty to the city in the wars against the Turks. During the Turkish siege of 1657, Jews distinguished themselves by successfully defending Fort Arniro, the northwest wing of Diocletian’s palace, from then on called the “Jewish Fort”.

On the eve of the Second World War, the Jewish community of Split consisted of around 300 members. Half of them were killed, either through deportation or in combat against occupying forces. After the war, there were only 163 Jews in Split. By the turn of the 21st century, only about 100 Jews remained.

The synagogue , which was completely ravaged by the Ustashis in 1942, is located in a building that also serves as headquarters for the small Jewish community. It sits in the city center on a tiny little street, or passage, near the People’s Square (Narodny Trg). The synagogue was reopened after the independence of Croatia. Work was carried out in 2016-2017.

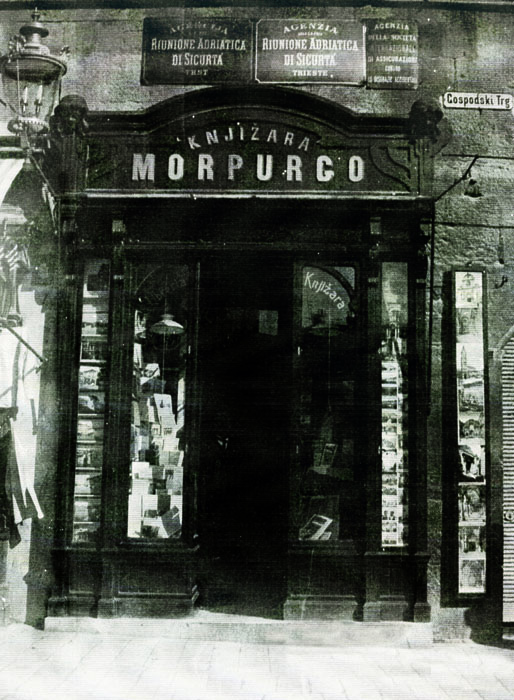

In the People’s Square stood the former Morpurgo bookstore . First opened in 1860, the shop features a plaque in memory of its founder, Vid Morpurgo (1834-1911), whose life marked Split in the nineteenth century. Vid (Vita) Morpurgo is best-known for his participation in Croatia’s growing national movement. He also established Split’s first lending library, founded a bank, and was soon invited to preside over the local chamber of commerce.

Built in 1578, Split’s Jewish cemetery sits on the slopes of Mount Marjan in an ideal setting. In magnificent surroundings, it contains over 200 tombs, mainly gravestones of which remain legible; the most recent ones are written in Italian. The names of some of the region’s famous ponentini (Venetian “wester” Jews) can be observed there, such as the Tolentino and Camerici families, and even the grave of a certain medical doctor, Raffael Valenzin, who died in 1878 at the age of thirty. It is also on Mount Marjan that Vid Morpurgo is buried. The most recent graves date from the start of the Second World War. The cemetery entrance is located beside a house that once functioned as a mikvah, transformed today into a café.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica