The Norman city is mainly known for its port, the second most important in France after Marseille. A port immortalized in the movie Le Quai des Brumes by Marcel Carné and Jacques Prévert, with Jean Gabin, Michèle Morgan, Pierre Brasseur and Michel Simon.

The community had existed since at least the 1920s, with the arrival of Tunisian Jews after the First World War. Previously there was a presence of Ashkenazi Jews who worked in Le Havre in the coffee and cotton trade and who largely resided in Paris.

Le Havre being nicknamed at the time the first port before the Americas, migrants therefore passed through the city to get there.

Some stayed behind, finding the living environment pleasant. For these same strategic reasons, Le Havre was a strategic hold for the German invaders who transformed the city into a naval base.

Léon Meyer, who was mayor from 1919 to 1940, adopted a policy of building affordable housing and increasing municipal social assistance services, which won him strong popular and worker support.

He also campaigned for equality between men and women. Removed from his functions by the Pétainist government, he was then deported and survived the camps.

There were 300 Jews in Le Havre at the dawn of World War II. The majority lived in the popular Notre-Dame district. The Jews had to flee and about fifteen were deported.

In all, 900 people are arrested in Normandy for their Judaism. 740 are deported. Meanwhile, the Resistance networks in Le Havre help British intelligence.

The synagogue on rue Victor Hugo has been attributed as war damage by the town hall. The old synagogue was in the district of Saint-François, near the beach and other areas bombed by the Allies before the D-Day landings.

The city of Le Havre was largely destroyed by these bombings carried out between 1942 and 1944, which was also the case for the synagogue and Christian places of worship, as well as institutional and cultural representations. Thousands of Le Havre died, caught between the two fires.

In 2017, around 20 volunteer high school students took part with their history and geography teachers in a major Holocaust mapping project in Le Havre. To retrace the persecutions but also to evoke the Jewish life of the time and to transmit this little known part of the history of their city.

In the 1950s, the community was given land on which there was a temporary caravan pending the granting of rights for the reconstruction of a synagogue.

A little later, a room was allocated which looked like a shed, transformed into a synagogue , rue Victor Hugo.

The North African Sephardim in the 1960s enabled the number of Jews to reach between nearly 220 families. In those post-war years, the community was chaired by Mr Bauer, owner of a large ready-to-wear store in the city center.

Rabbi Solomon Abikzer accomplished some important work to unify the Jewish community of Le Havre, Ashkenazim and Sephardim, especially in the ritual. For example, the rabbi printed a sidur where the two rituals were included, a sidur used for the Tishrei festivals.

From 1965 to 1978, Armand Renassia was elected president of the community. It continued its development, in particular through the creation of a cultural space, the presence of Wizo and the Women’s Cooperation led by Jacqueline Elalouf. And that of youth movements like Dejj and Betar. All hosted in a rented building in the city. His son Denys was then elected to take over until 1983. Arnold Juris succeeded him, then Jacques Elalouf in 1986.

The structure of the synagogue is quite original. With a double glazed ceiling on the roof which allows light to take up a lot of space in the place, as well as stained glass windows on the sides. Victor Elgressy, the current president since 1998, carried out renovations inside the synagogue in 2020 but the structures remain similar. With Rabbi Dov Lewin by his side. Around 100 Jewish families now live in Le Havre.

Page written with the help of Denys Renassia.

Sarah Hakon Attal, who spent all her youth in Le Havre, tells us about the life of this small, very dynamic community. She is currently a coach and trainer in neuroscience in Paris.

Jguideeurope: What does the synagogue in Le Havre represent for you?

Sarah Hakon Attal: The synagogue in Le Havre represents for me a place of worship and much more. We went there with my father, Guy-Pierre Hakon, on Friday evenings, Saturday mornings and during the holidays to pray and meet other members of the community.

Rabbi Salomon Abikzer and President Armand Renassia, then Denys Renassia and Jacques Elalouf, ensured that a warm atmosphere reigned in the synagogue.

After prayers, we would organize Shabbat meals and seders together around large tables filled with food prepared by the families. Rabbi Abikzer created unity among the faithful and transmitted the values of Jewish life. His wife Flory, always present, received us in their house.

On Friday nights, my father regularly brought surprise guests home. My mother, Nadine Hakon, then took charge of preparing enough couscous to accompany these moments of joy and warmth. The Havre synagogue is still located in the same place, rue Victor Hugo, in front of my primary school, La Mailleraie.

What are the other emblematic places of Jewish life?

The places were those of gastronomic meetings, in the establishments of the city and especially the ones at the others. Among the restaurants, the Select, run by Jacques and Jacqueline Elalouf and their Brasserie du Théâtre. Many festivals associated with Jewish life in Le Havre, such as bar mitzvos, were organized at the Select. On Saturday and Wednesday afternoons, we practiced shotokan karate at Master Emile Elalouf’s house and afterwards, all together, we went to taste the Brasserie du Théâtre to savor the pastries.

The lunches or dinners at Sol Elalouf, nicknamed MamaSol by her entourage, were exceptional. MamaSol would ask me to sit next to her on her sofa, I was flattered and happy with our saying smiles.

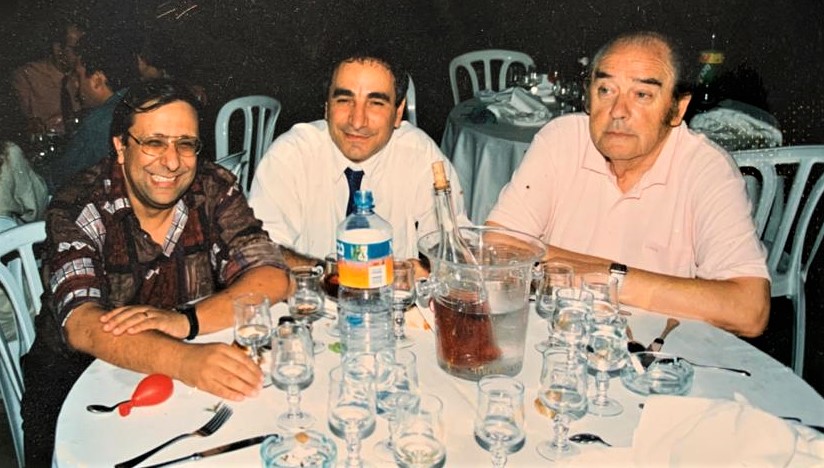

Other emblematic places, endless and fascinating aperitifs with the Renassia, Taieb, Princ, Guedj, Loutaty, Sasportas, Elalouf, Elgressy, Blum, Sevi, Cutas, Tayar, Sembel, Goldfarb, Revah, Zysman, Donnard, Benchetrit, Safar, Chetboun, and Juris families … And with us.

Sephardic and Ashkenazi traditions were shared with enthusiasm by all members of those traditions. I have come to appreciate Dora Juris’s kneidlers. Since then, I prepare this Ashkenaz specialty every Passover. The Mimouna, celebrated after Passover, was incredible. I began to eat couscous with butter, as the Moroccans prepare it, at my mother’s house.

I joined my friends to tour the houses and taste the moufletas of Salomon Elalouf, then those of Odette Cohen and Madame Asséraf. All washed down with the traditional drink from our tables, the Phoenix of Moïse Taïeb.

There was a very pleasant Jewish life in Le Havre and throughout the region. We also organized balls with the communities of Rouen and Caen. Thus, for one evening, a fusion of the three cities took place with music, meals, dancing and laughter. During the holidays, Monique Cohen Berda and Martine Asséraf performed oriental dance demonstrations.

Many of my friends made their alya in Israel. My father did not want to leave me alone, and I left Le Havre when I was 15 at the Maimonide high school in Boulogne.

But there are still many families carrying on the same enthusiasm as 30 years ago. This community continues. When on vacation I see some Havre people again, it is as if I had left them the day before.