The Golden Horn is a small estuary created by two rivers that flow into the Bosporus. From one side of the Golden Horn to the other extend traditional Jewish neighborhoods that arose beginning at the time of Jewish settlement in Istanbul in the Byzantine period. Even at the beginning of the twentieth century, more than half the population of the Balat was Jewish, although many were already leaving the cramped houses of this humid district for the “European city”.

The neighborhoods of the Balat, on the right bank, and of Hasköy, on the other side of the river, have remained vibrant and rather exotic in memories of Istanbul -places where Ladino was spoken and one lived according to the rhythms of Jewish festivals and the Shabbat. The names of synagogues, many of which have since disappeared, recall the Sepharad that everyone keeps close to their hearts (Gerouche-Castile -the exiles of Castile-Catalan, Aragon, Portugal, Senioria…). Many European travelers of the nineteenth century gave terrible descriptions of this quarter. Edmondo de Amicis, for example, described it as “the vast ghetto of Balat stretching out like a foul serpent along the Golden Horn with its mold-encrusted huts.”. Marie-Christine Varol offered a more even-handed portrait in her monograph on the Balat: “All manner of social classes are found mixing in the Balat, from well-off merchants to the most humble street peddlers and ragpickers.”.

As in the rest of Istanbul, the many wood houses were vulnerable to devastating fires. The volunteer fire brigade thus held a key place in the life of the community. The houses near the docks (the Karabas area) have been knocked down to make room for a park and an enbankment. Recent Anatolian immigrants occupy most of the small buildings abandoned by Jews. Only a few Jews still live in the area, notably close to the Ahrida Synagogue. These are mainly poor families living on aid from the community. Some Jewish doctors keep an office in the area, near the large Jewish hospital Or Ha-Haïm, which is still active. The inscriptions on the stone facades of the houses and several synagogues still standing in the area evoke memories of its former life. A visit to Balat and Hasköy necessitates a full day.

The fire of 1911

“In 1911, part of the Or Ha-Haïm hospital located in Balat burst into flames and was engulfed in fire. The entire Dibek quarter, including the Gerouche Synagogue and the two Israelite Alliance schools, a part of the Sigri quarter with its synagogue Pol Yacham, the entire Hevra quarter and its synagogue and Talmud Torah, and a large part of Balat fell prey to the flames. Caption: 520 buildings destroyed, 1000 families without shelter…Outside the municipal and communal aid, the gifts of strangers are rapidly amounting to more than 60,000 francs.”

Avram Galanté, History of the Jews of Turkey. (Istanbul: Isis, 1985).

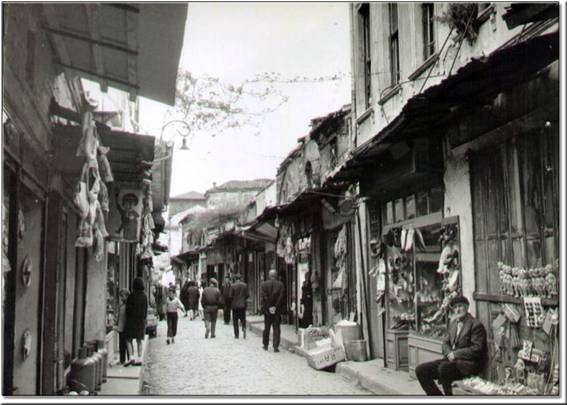

The lively main street of Kürkçü Cesmesi, like the nearby Leblebciler and Lapincilar, is the center of commercial Balat and animated every day except the Shabbat. On Saturdays, the area is dead, a place where even the Turkish and Greek merchants respect the sacred day of rest. Most of the shops at the front of the houses are owned by Jews. The area was known for the manufacture of the fez until this traditional headpiece was outlawed by the republican authorities in 1928. There are also cobblers and makers of Turkish slippers, often Jews from Georgia (los gurdjis). At 6 and 8 Eski Kasap, the street perpendicular to Kürkçü Cesmesi, you can still see two lovely Jewish homes, with a Star of David on the corbelled facade and the inscription “Prosperity on the family”.

The Ahrida Synagogue is the oldest continuously active synagogue in Istanbul. Founded in the fifteenth century by Jews from the Macedonian city of Ohrid, it is also incontestably the most beautiful. The synagogue has kept the name of the small Romaniote community that established it, even though this community was absorbed by Jews arriving from the Iberian Peninsula, who gave the temple its splendor. According to legend, the false Messiah Sabbataï Zevi once preached here.

The main building was rebuilt at the end of the seventeenth century and restored several times thereafter, each time keeping the general outlines of the original design. The large rectangular prayer hall is crowned by a wooden dome, and its ceiling is painted with elegant, typically Ottoman floral motifs. Resplendent with eight columns and ten large windows, the synagogue is luminous. The most recent large-scale restorations, completed in 1992, have returned the hall to its former design, most notably by getting rid of the women’s balcony. As in earlier times, women follow the service from an adjacent hall separated from the main worship space by perforated panels. A unique tevah stands in the center of the hall. Made of varnished wood in the form of a ship, it represents Noah’s Ark and also explicitly evokes the caravels that carried Jews fleeing Spain. The prow points toward the aron, which features magnificent ivory and mother-of-pearl inlaid wood doors. Two other buildings are located in the garden, the Midrash and a heavy stone and brick structure, the old odjara. The latter today serves as a hospice.

Several hundred feet from the Ahrida Synagogue stands the Yanbol Synagogue , the other main synagogue preserved in Balat. Bearing the name of the small city in Bulgaria where the members of the founding community originated, the synagogue was rebuilt in the eighteenth century and restored several times subsequently. Illuminated by its numerous windows, the large hall is crowned by an elegant wooden ceiling decorated with floral and other motifs. The capitals of the columns are finely carved and painted. The tevah in the middle of the hall faces the aron, whose wooden doors are inlaid with mother-of-pearl and ivory like those of the Ahrida Synagogue.

Nearby, at the corner of Feruh Kahya and Mahkme Alti streets, you can visit the old cavus Hammami , frequented by Jews of the quarter, who called it “el bano de Balat”. In both the men’s and women’s areas of the facility, there is a basin reserved as a mikvah for purification.

Going back up the hill toward Balat and the Saint Savior in Chora (Kariye Camii), famous for its mosaics, you will come to the impressive Ichtipol Synagogue . Made completely of wood, the synagogue has a beautiful round stained-glass window bearing two interlaced Stars of David. It was established in the first years of the Ottoman Empire by Jews from the small Macedonian town of Ichtip. Devastated by several fires, it was reconstructed for the last time in 1903. facing at number 63 and 67 on the same street are two beautiful homes notable for their corbelled wooden facades and finely carved decorations. They were once occupied by Jewish families of the area, who, even at that time, had already begun to occupy parts of the neighboring Greek enclave.

The remains of several other synagogues can be found in Balat, sometimes reduced to a simple door, such as that of the Kastoria Synagogue, at 132 Hoca Cakir Street. Along Demir Hisar Street, one can make out the ruined walls of the Eliahuh (at number 231) and Sigri Synagogues. The former Egri Kapi cemetery, which closed in 1839, is now completely abandoned and being devoured by neighboring construction projects. The tombstones bearing inscriptions have been transported to the cemetery in Hasköy on the other side of the Golden Horn.