In northern Belarus, on the road to Moscow and Saint Petersburg, Vitebsk symbolizes all the Jewish shtetlach of Russia immortalized in the work of Marc Chagall, who was born here in 1887 and lived here until 1907, and again from 1917 to 1919. In the era of Chagall’s childhood, Vitebsk had a Jewish majority (there were 34420 Jews here, or 52% of the population), as depicted in the images he bequeathed to us: the describe, in a playful and fantastical way, the shtetl with its various rabbis, synagogues, livestock traders, tavern keepers, rooftop violinists, and ancient cemeteries. His best-known evocations of Vitebsk are Red Gate, Blue House, The Synagogue, Cemetery Gates, and Above the City.

Vitebsk was also home to the Hasidic master Menahem Mendel, a student of the Great Maggid of Mezritch. Numerous churches, both Catholic and Orthodox, dotted the city center. The center has lost much of its charm, however, as many of these buildings have since been destroyed. Vitebsk nevertheless remains the most artistic and visited city in Belarus. The City Museum of Fine Arts welcomed in 1997 the first Chagall exhibit ever to be held on the painter’s native soil, thus marking a milestone in the cultural life of the nation. On Souvorov Street, the palace can still be seen where Napoleon, on the road to Moscow, stopped for a few days after capturing the city.

To locate the former ghetto and visit Chagall’s childhood home, cross the Dvina River, take Kirov Boulevard, turn right on Dimitroff Street, and finally left to Pokrovskaya and Revolutionnaya streets. At this intersection, a sculpture of the painter can be seen. Continue along Pokrovskaya Street down to number 29, the house where Chagall spent his childhood years. You will find several Jewish religious artifacts, photographs, and furniture that perhaps belonged to the artist’s family. In the courtyard stands another statue of Chagall.

Next take Revolutionnaya Street, which provides a glimpse of what the ghetto once looked like. At number 14 lie the ruins of the former synagogue, of which only the facade remains.

Mogilev, on the Dnieper, was for many years a Jewish majority (21539 Jews in 1897, or 50% of the population). As elsewhere, the ghetto was annihilated during the occupation. Traces of the former Jeish quarter are easily spotted in the center of the old town.

Turn right on Karl Liebknecht Street to find, at number 21, the building that housed the former synagogue, transformed today into a fitness center. If you walk around it to the adjoining building and pass under the porch, you will enter a Jewish-style courtyard facing 27 Lenin Street. The entire residential block is remarkable.

In 1897, 20385 Jews lived in Gomel (54,8% of the population), as compared with 37475 (43,7%) in 1926. Today, little remains of their life here. The Jewish quarter was located on the right bank of the river.

A beautiful synagogue with colonnades once occupied the slight bend that forms on the main road (Lenin Street). In its place stands the Mir Cinema, whose columns -those of the former synagogue- give the theater a temple-like presence. The streets in front of and surrounding the cinema appear to have once been Jewish.

The cemetery, now in ruins, is located to the left just beyond the southern edge of the city.

Grodno, seat of a Catholic bishopric, was once a major city within the Polish-Lithuanian Union, as evidenced by Farny, the beautiful Baroque Jesuit church that towers over Sovietskaya Square. Jews began settling here in the fourteenth century: they were permitted to live in the town by Grand Duke Witold in 1389. In the nineteenth century, over 60% of the population was Jewish; at 42% in 1931. The city contained many synagogues, yeshivot, and study groups presided over by the Mitnaggedim. Grodno was a hub for both the Bund and Zionism.

The Grand Synagogue was located downtown on Witoldowa Street (now called Sotsalistichnaya). The building, though neglected, still stands at number 35. The Jewish quarter, properly speaking, was located a little farther away from the central square, between Zamkowa Street and the fish market (rybi rynek), around Pereca and Nochima streets. The majority of these streets no longer exist. In their place runs a thoroughfare named Velikaya Troitskaya; you will need to refer to an old map of the city to get a sense of the former Jewish district.

On Zamkowa Street, at its intersection of what used to be Ciasna Street, a door crowned with a Star of David marks the entrance to the former ghetto; a plaque recalls the murder of its 29000 residents. Several houses in ruin can still be seen, as well as the old synagogue on Velikaya Troitskaya Street, almost at the edge of a ravine. A plaque reading “Jewish Community of Grodno” is the only sign that it is still active. A little farther away, at Velikaya Troitskaya Street 13, there is a smaller synagogue that now functions as a school. Nothing remains of the old cemetery, which was located on nearby Krzywa Street.

In the nineteenth century, more than 70% of Slonim’s population was Jewish. The ratio was 53% before the war.

The ghetto was burned down between 29 June and 15 July 1942. At the city’s edge, at the site of the former cemetery, a monument commemorates the city’s 35000 Jews exterminated during the war.

In the city center, set back in the relation to the marketplace, the ruins of a magnificent Baroque synagogue can be seen. Built in 1642, it is still standing, but in deplorable shape inside, though certain bas-reliefs (two lions presenting the Ark of the Law) and frescoes depicting musical instruments and biblical landscapes have been preserved -a unique event in Belarus. The market is located around the synagogue. Urinals, moreover, have been installed right up against the walls of this historical monument.

It is worth exiting the highway midway between Brest and Minsk and heading toward Slonim: in the middle of the village of Ruzhany, a beautiful synagogue still stands today. Its roof is in imminent danger of collapsing, however.

The first city across the Polish border, Brest is located on the right bank of the Bug River. Its name evokes the famous Brest-Litovsk Treaty of April 1918, whereby Trotsky’s Red Army put an end to the war with Germany by ceding to the latter large amounts of Russian territory (the treaty was annulled in November of that same year by the Soviet government). On 22 June 1941, in Brest, Hitler’s columns began their violent march across the Soviet Union.

Brest-Litovsk had for many years a Jewish majority. According to the 1936 Polish census, the city contained 51170 inhabitants, of whom 21134 were Catholic (the Poles), 8228 were Orthodox Christian (Russians and Belarusians), and 21518 were Jewish (or more than 40% of the total).

In 1941, the Germans created a ghetto around Sovietskaya and Dzerzhinsky Street up to Macherova Street. In April 1942, all of the ghetto’s 19000 residents were deported, taken in cattle cars to the village of Bronnaya Gora, thirty miles to the east, and murdered and thrown into eight huge mass graves. Among them was the mother of the future Israeli prime minister Menachem Begin. A unique case in the history of the Shoah, the exact identity of every victim was recorded before their deportation, including both a photo and fingerprint; these files are preserved in the Brest archives, as documented in Ilya Altmann’s 1995 film The Brest Ghetto.

The entire downtown (around the present-day Karl Marx, Dzerzhinsky, 17 September, Macherova, Sovietskaya streets, and Liberty Square) was Jewish and contained many synagogues. The main one was located on what is now called Sovietskaya Street; it has been converted today into a movie theater, the Belarus. Another synagogue stood at the intersection of Dzerzhinsky and 17 September; it is now residential housing. Notice as well the housing block at the corner of Macherova and 17 September, with its stores and courtyards of typical Jewish architecture. The Jewish hospital, today a regional medical clinic, was located at 24 Sovietskikh Pogranitchnikov (Soviet Border Guard) Street, while the adjacent synagogue has been turned into office space.

On Macherova Street, near the Tets tram stop, the ramp used for the loading and departure of the trains can still be seen. At 43 Dzerzhinsky Street, a monument has been erected in memory of the victims of the ghetto.

The city of Bobruysk was once a typical Belarusian shtetl. In 1897, 20759 Jews lived here (60,5% of the population), while in 1926, the Jewish community had a population of 21558 (42%).

To form an image of what a Jewish city once looked like, explore the downtown area of Dzerjinsky Street and its marketplace. Stroll down Karl Marx Street and Komsomolskaya Street with their typical balconies, then take Socialistitcheskaya Street, which had a synagogue at numbers 34-35, now the site of a clothing workshop. Finally, be sure to explore the crowded Tchongarskaya Street, on which another synagogue once stood at number 31, in ruins today. Downtown as a whole resembles certain old photos of Jewish villages -without their inhabitants, however, as the majority have either died or moved away.

The Jewish cemetery is located outside the city along the route to Minsk (Minskaya Street), on the right just upon leaving town. It is huge for such a small city, and well maintained and still much visited.

Minsk, the capital of Belarus, first welcomed Jews in the fifteenth century. They settled here to engage in the trade between Poland and Russia. After Poland was divided, the Jewish community began to grow: it consisted of 47560 members at the time of the 1897 census, or 52% of the population.

The Germans arrived in Minsk on 28 June 1941, only six days after launching their offensive, and the occupation was particularly violent. The ghetto was created on 15 July and extended across Khlebnaya and Nemiga streets, the Street of the Republic, Ostrovsky Street and Jubilee Square, and streets including Obuvnaya, Chornaya, Sukhaya, and Kolleltornaya. The Germans committed abuses, crimes, and mass executions, notably those of 7 November 1941, 2 March 1942, and 18 July 1942: thousands of people were beaten, murdered, or gassed in trucks used as gas chambers and tossed into mass graves in either Toulchinka or the “hole” (lama) on Zaslavskaya Street. German Jews were also deported to the Minks ghetto. On 14 September 1943, they were all loaded onto trucks and gassed.

Between 1941 and 1943, the Minsk ghetto was the largest in occupied Europe. More than 100,000 Jews lived in inhuman conditions. The Zaslavski Memorial marks the place where the Nazis assassinated 5000 people during the same day in March 1942. Nearly 500 bodies were rushed hastily into an adjoining pit. This is what the sculpture imagined by Levine represents.

Just steps from the memorial, you can visit the Holocaust Museum. Located in the old Jewish quarter and founded on the initiative of the ghetto survivors, the museum is housed in a century-old Jewish house, in front of an old cemetery. Each piece of the museum exhibits the daily life of a Minsk family. You will also find German military documents and original photographs of the Maly Trostenets concentration camp, and a memorial in honor of 33,000 European Jews deported to Belarus.

On the campus of the Jewish University of the city, you can also visit the Museum of Jewish History and Culture, where more than 10,000 objects are preserved. These artefacts are all donations, the oldest dating back to the nineteenth century. The permanent exhibition also traces the life of Belarussian Jews from the 14th century to the present day and includes an interesting section on the role of women in Judaism.

The neighborhood of the old ghetto still exists, but it is unrecognizable. Destroyed by the Germans, it was rebuilt in the Soviet, as was the whole city. The most important remnant of the Minsk ghetto is the location of the “hole” (lama) at the corner of Melnika and Zaslavskaya Streets, where many Jews were executed. On July 10, 2000, a sculptural group of great magnitude, the work of the sculptor Lévine, representing women, old men and children descending into the tomb, was inaugurated in the presence of President Lukachenko, important personalities and a large crowd.

The only active synagogue in Minsk today is in the north of the city. The building is big, but the room inside is relatively small.

In recent years, the Belarusian government has made progress in its research efforts on the country’s Jewish past. The best proof of this is the inauguration by the President of the Republic himself of the Maly Trostenets Camp Memorial, financed by the government. It should be noted, however, that the text of the Memorial does not reflect the fact that the vast majority of the victims of the camp were Jewish. “Minsk residents” and “deported citizens of Europe” rub shoulders with supporters and anti-fascists. However, the opening of this memorial is still a step forward.

For several reasons, Maly Trostenets is one of the least known concentration and extermination camps in the history of the Second World War. First, there were only very few survivors. Originally thought of as a labor camp after the invasion of Belarus by Nazi Germany, the camp was quickly turned into a death camp and was in operation between May 1942 and the end of 1943. The victims were mainly Jews of the Minsk ghetto. Convoys also arrived from German cities or from Vienna. The victims were usually shot as soon as they arrived in an adjoining forest. The gas trucks experienced in Chelmno were also used at Maly Trostenets.

Until today, it is complex to establish the number of exact victims of the camp. All traces were destroyed by the Nazis at the arrival of the Red Army in 1944. They are estimated between 40,000 and 200,000.

The most important monument of the Maly Trostenets Memorial is a sculpture entitled “Gate of Memory”. it is accessed by the “Route of Memory”, which exposes in three languages (Belarusian, Russian and English) on the dark granite the names and locations of the main places of mass extermination of Belarus, and the number of victims. At the end of this road, an informative panel presents the site in its entirety and marks the places where original foundations were found. The visit lasts about an hour.

For nearly two centuries, Stolac was the destination for a pilgrimage to the grave of rabbi Moshe Danon. In 1820, Grand rabbi of Sarajevo Moshe Danon and ten other prominent members of the Jewish community were accused of assassinating a local dervish, a Jewish convert to Islam named Ahmed. The pasha of Sarajevo threatened the death penalty unless they handed over a ransom of 500000 groschen, an impossible sum to raise. Sarajevo’s Jews the requested the help of the city’s Muslim residents, who in tun stormed the prison, freed the captives, and obtained the contemptible pasha’s removal by the sultan. Ten years later, on his way to Palestine, Moshe Danon fell ill at a stopping point in Stolac, where he died. Soon after, the practice of a pilgrimage to the site came into being, every first Sunday in July.

The city’s Jewish cemetery, which dates back to the eighteenth century, was severely damaged during the 1992-95 war, though it has been partly rebuilt since. The city still houses a tiny Jewish community.

When the grand vizier Syavush Pasha came to Sarajevo in 1581, the local representatives of the Sublime Porte asked him to separate the Jews from the rest of the population, for “they lit too many fires and made too much noise”. Syavush Pasha ordered the construction of communitarian housing for the Jews, with a courtyard and synagogue. The Velika Avlija (Old Temple Synagogue) offered forty-six bedrooms to the city’s poorest Jews, while the rest of the community lived in the other mahallahs (districts) of the city. Enjoying freedom of movement from that point on, Jews in Sarajevo never lived in ghettos, strictly speaking.

Destroyed by a fire in 1879, the Velika Avlija has never been rebuilt, with the exception of its synagogue. It houses today the small Jewish Museum of Sarajevo, which features various collections of clothing and religious objects, some of which originated in Spain.

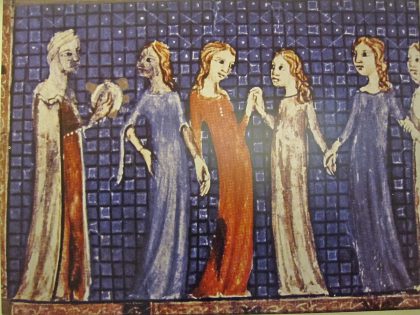

The Haggadah of Sarajevo, a famous fourteenth-century illumination, recounts the parting of the Red Sea. It was brought to Bosnia by Catalonian Jews. After many trials and tribulations, it has ended its journey in Sarajevo, where it is preserved at the National Museum of the Republic.

The modern synagogue was built in Moorish style in 1902 by Ashkenazic Jews; it is decorated with superb arabesques, and today serves as the Jewish Community Center.

The old Jewish cemetery of Sarajevo is located in Kovacici, on Mount Trebevi overlooking the city. Founded in 1630, it shelters a large number of graves with inscriptions in Judezmo that are still legible. The cemetery unfortunately served as a strategic position during the civil war of 1992-95: the Bosnian Serbs set up their artillery here to bomb the city from above, at the same time drawing gunfire from those under siege below. The Bosnian Serbs also mined the site before the withdrawal. A private Norwegian organization has since then been hired to clear the area of mines.

In Vrace, not far from the Sarajevo cemetery, a monument honors the memory of the city’s 9000 residents massacred during the Second World War, including more than 7000 Jews. Their names and ages have been inscribed on the inner walls of the old fortress, which has since been turned into a memorial.

Subotica’s synagogue, built in 1903, was converted into a theater after the war. The building was renovated in 2005. It is located in the city center a few steps from city hall.

In the Jewish cemetery, a monument commemorates the victims of the Shoah.

The Jewish community of Voivodina’s capital was, until World War II, one of the most prosperous in all Yugoslavia.

Present since the city was founded in the late seventeenth century and 4000 members strong before its extermination, the community was keen on building structures to rival those of other ethnic groups in this majority-Hungarian Catholic city (it belonged to the Austro-Hungarian Empire until 1918).

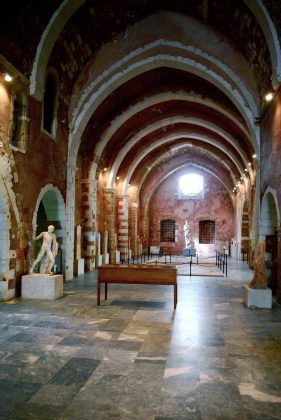

The Municipal Museum of Novi Sad, set up in the former Petrovaradin fortress, has a collection of relics gathered from the Celarevo archaeological site, located around eighteen miles west of the city on the shores of the Danube.

Hundreds of bricks fragments bearing various symbols (menorot, shields of David, Hebrew markings) are on display here, they date to the late eighth and early ninth centuries, when the region was under domination by the Avars.

Researchers have advanced the hypothesis that this people of Mongolian origin had been influenced by the Khazars of Crimea, a tribe that had itself converted to Judaism during the eighth century.

Built in 1909 in the so-called “Neolog” style (modernist Ashkenazic, as opposed to Orthodox), the synagogue is the work of Hungarian architect Lipot-Baumhorn, to whom we owe forty-some synagogues in eastern Europe.

It remains one of the largest synagogues in Central Europe, with a dome 120 feet high and 40 feet wide, a three-nave basilica, and a seating capacity of 900. Along with the adjacent buildings that housed Jewish community activities (mikvah, slaughterhouse, school, retirement home, orphanage, cultural center) built several years later, it was spared during the war by its Hungarian and German occupants.

This was not the case for its people, however: the synagogue was used as a temporary concentration camp for Jews of the region before their deportation to various death camps.

After the was, when Novi Sad contained no more than 300 Jews, community leaders negotiated with Yugoslavian authorities for the donation of the synagogue, whose excellent acoustics were underscored by cantor Mauricius Bernstein.

The temple has served as a concert hall ever since. Services held here are of only secondary concern.

Renovation projects on the site from 1985 to 1991 have uncovered the stone Decalogue of a previous synagogue built here in the late eighteenth century.

Beside the Danube, a monument honors the memory of the city’s thousands of inhabitants, both Jewish and Serbian, shot down or thrown in the river by Hungarian militias on 23 January 1942, in revenge for an assassination committed by the Resistance.

The city also has a Jewish cemetery.

A monument dedicated to the victims of the Shoah has been put up on Bubanj Hill. The former synagogue today serves as an art gallery and the Jewish cemetery was rehabilitated in 2004.

After the conquest of Belgrade by the Turks in 1521, Sephardic Jews quickly supplanted in number the Ashkenazic community that had arrived before them, from Hungary in particular. Loyal Turkish subjects, Belgrade’s Jews enjoyed an initial phase of relative prosperity, transforming the city into one of the premier Sephardic centers in the Balkans. The Belgrade yeshiva was known throughout Europe, thanks to the reputation of rabbis like Meir Andel, Yehuda Lerma, and Simha ha-Kohen, who had to public their books abroad, lacking a suitable printing press at home.

The Jews suffered, however, at regular intervals during the Austro-Turkish wars, repeated assaults on the city in the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries.

When the Austrians seized Belgrade in 1688, they sacked the Jewish quarter of Dorçol and captured a portion of its residents, forcing their fellow believers to buy them back.

The city’s great Sephardic rabbi, Joseph Almoslino, counted among the victims. This did not prevent the Turks, in their turn, from reproaching the Jews for failing to retreat with them, unleashing a new wave of persecutions.

The Jews later tied their fate in large part to that of Serbia’s movement for national emancipation, supplying the insurgents with arms and munitions during the anti-Turkish revolt of 1815. Thus, in 1830, when the sultan agreed to a statute providing autonomy to Prince Milos Obrenovic’s Serbia, they were granted civil rights equal to those of other citizens.

Many Jews joined the ranks of the new Serbian state, most notably the army, where they formed the prince’s personal guard, while one of them, Joseph Slezinger, directed the military orchestra. The prince authorized as well the printing of books in Hebrew in Judezmo.

The community’s status noticeably began to erode under the reign of Prince Mihajlo Obrenovic, who succeeded his father in 1839. A scandal involving ritualistic crimes contrived by anti-Semitic circles exploded in 1841. A pogrom took place in the fortress city of Sabac in 1865. It was only after the Congress of Berlin in 1878, which required all the Balkan states to grant complete equality to all ethnic and national minorities, that the Jewish community began to grow and prosper here, especially in Belgrade.

The historic district of Jalija and Dorçol, on the banks of the Danube, soon became too cramped: while the Ashkenazic community began settling the banks of the Sava River, the Sephardic population climbed the hill up to Prince Mihajlova Street and Terazje Square, where they opened some of the city’s most beautiful shops at the turn of the century. Religious institutions and buildings remained in Dorçol, however, a quarter which, before the Shoah itself, would be largely destroyed during the terrible bombardment of Belgrade by the Luftwaffe in April 1941.

This is why there remains little trace of Jewish life in Belgrade, with Jews numbering around 2000 before the war in Kosovo in 1999. In Dorçol, a monument to the memory of the Jewish community was recently put up on the bank of the Danube by Jewish sculptor Nandor Glid.

The Jewish Historical Museum presents a history of Jewish life throughout the former Yugoslavia, with a collection of religious objects, clothing typical of the country’s Jewish communities, and photographs, as well as from more ancient history in the region.

Of the three religious edifices in Belgrade before the war, only one synagogue still serves as a house of worship. Built in 1926, the Sukkat Shalm synagogue was transformed into a military brothel by the Nazis and rehabilitated after the war with German reparation money. The other synagogues have been destroyed. Among them, the Zemun sephardic synagogue, which was severely damaged by allied bombings.

The Jewish cemetery contains most notably an impressive monument to the victims of the Shoah and the Jewish combatants during the Balkan Wars (1912-13) and the First World War. There’s also the Jewish cemetery of Zemun.

A national hero

It was in splendid Kalemegdan Park, between the Sava and the Danube, that Moshe Pijade, the most famous Jewish Communist poet of the Tito era, was buried in 1957. Yugoslavian Communist Party pioneer in the 1920s, Pijade was one of the principal collaborators with the future Marshal Tito during the Resistance. After the war, Pijade in particular arranged the departure to Palestine of 6000 of the 14000 Yugoslavian Jews who had survived the genocide, before obtaining the post of National Assembly president.

Within the Venetian outer walls of ancient Candia, the old Jewish quarter is found right beside the seafront. Four synagogues once stood in this district, its perimeter today delimited by Venizelou, Makariou, and Giamalki streets. The last, still active at the start of the Second World War, was bombed. The Hotel Xenia has been built upon its ruins.

Several neighboring Venetianhouses were inhabited by Jews, as was the building housing the Historical Museum. Two sculptures in its Heraldic collection depict tow crowned lions brandishing sabers. They once belonged to the powerful Sephardic Saltiel and Franco families.

The oldest synagogue in Canea, Etz Hayyim, lives again after a half century of neglect. Raised from its ruins by Nicholas Stavroulakis, former director and founder of the Jewish Museum of Athens, it was rededicated in October 1999. (It should be noted that its reopening was violently protested by the island’s prefect.)

Etz Hayyim appears to have been the former Venetian oratory of Santa Caterina, yielded to the Jewish community in Canea in the seventeenth century by the Ottomans. It is designed after Venetian-inspired Romaniote synagogues: the main entrance faces north, while the aron kodesh and the bimah face each other on an east-west axis. Both synagogues were rebuilt with exotic wood, made possible by donations.

From the southern wall, a door provides access to an upper floor where women were permitted. The mehizah is also accessible by way of the courtyard. The roof of the ritual bath, the mikvah, located on the first floor, has also been redone. Numerous inscriptions have been uncovered as well.

A second temple, the “New”, or Shalom Synagogue, once stood in this district, still called Evraiki to day (“Jew” in Greek). It was completely destroyed by bombardments during the 1941 Battle of Crete.

The Archaeological Museum, located on Halidon Street, an artery parallel to Kondylaki Street, contains evidence of Jewish life in Canea. In an outdoor courtyard, six medieval epitaphs in Hebrew are on display. Inside, three other, more recent ones can be viewed as well.

In the fourteenth century, a Jewish community settled behind the ramparts of Rhodes erected by the knights of Saint John after their flight from the Holy Land. These Jews had the strange destiny of finding common ground with the Crusaders in their war against the Ottomans, only to be forced by Grand Master Pierre d’Aubusson to convert to Christianity or flee.

The waves of expulsion from the Iberian peninsula brought many Sephardic Jews to the shores of Rhodes. Glimmers of rabbinical quarrels between these new arrivals and the Romaniote Jews settled here much earlier were recorded in numerous responsa. In the first half of the twentieth century, the Jews of Rhodes emigrated, in particular to Rhodesia. The vast majority of the 2500 Jews who remained on the island were deported by the Nazis in July 1944.

La Judería

In the eastern section of the old medieval city, the former Jewish quarter, la Judería, begins at the square called Evreon Martyron (Of Jewish Martyrs). In the 1920s, the district contained six synagogues, and 4000 Jews lived there. Walk along Pindarou Street, then turn left down Dosiadou Street, where you will find the Kal Kadosh Shalom Synagogue. If you head back up Pindarou Street, you will find a Hebrew plaque at 4 Byzantinou Street that blesses all those who pass beneath its arch. It is dated Nisan 5637 (1837).

The tour continues up to the old Puerta de la Mar, then right along the ramparts on Kisthiniou Street, where the Grand Synagogue of Rhodes and the Universal Jewish Alliance School once stood. A plaque recalls the existence of this institution, founded at the turn of the century thanks to a gift from Baron Edmond de Rothschild, who visited Rhodes in 1903. This was the first mixed school here, with teaching conducted entirely in French. It was destroyed by bombardments during the war.

The Kal Kadosh Shalom Synagogue

A single synagogue, Kal Kadosh Shalom, remains in Rhodes. Well restored under the care of the significant Diaspora community, it was first built at the end of the sixteenth century. On the fountain in the courtyard, the date Kislev 5338 (1577) gives a sense of its age. The main door leads to the synagogue; on the left, a small entrance leads to the upper , women’s section built in the middle of the 1930s. Before then, women were confined to the rooms adjacent to the temple southern wall.

The interior layout, with the tevah in the center, is typically Sephardic. The western wall peculiarly possesses a door to the courtyard with two aronot kodesh with neoclassical capitals for the Scrolls of the Law on either side of the door. The little courtyard once led to the yeshiva, which was destroyed during the war. The floor is covered with a black and white stone mosaic, as found in other buildings of old Rhodes. Decorated during the nineteenth century, this synagogue exudes real charm with its Ottoman architectural influence. Numerous plaques celebrating donors, including the Adlaheff family, are written in Judeo-Spanish, Ladino or Judezmo.

The cemetery

In the 1930s, the Italian occupying authorities moved the ancestral Jewish cemetery beyond the ramparts; it is now located in the modern city. Important restoration work in 1997 has revealed some 200 graves, several of which date back to the sixteenth century. The names figuring on the tombstones are those of Sephardic families from the Ottoman Empire, with dedications in Judezmo and abbreviations in Hebrew, like those of Moshe Sidi (1593), Dona de Carmona (1671), and the “humble, honorable, pure” Reina Hasson, who died on the seventeenth day of Tishri in the year 5623 (1863).

For more information about the Jewish Rhodes, visit the websites of the Jewish Museum of Rhodes.

Visiting the site in Delos is quite easy throughout the summer, the island being accessible by boat from nearby Mykonos.

If one place attests to the presence of a Jewish community in Ancient Greece, it is certainly that of Delos, an arid island of the Cyclades. The existence of Jews here is referred to in the Book of Maccabees, while Flavius Josephus mentions them as well. Too tiny to flex any real political muscle, the island was an important religious center and cosmopolitan trade city, however, comparable in Hellenestic period to Pompeii. During that era, Delos had as many as 30000 inhabitants, hailing from all parts. Merchants guilds were established here, including ones from Alexandria, where Jews were numerous. Such prosperity, which lasted until the dawn of Christian era, certainly drew Jews here, such as Samaritans. Nevertheless, their history remains unknown to us.

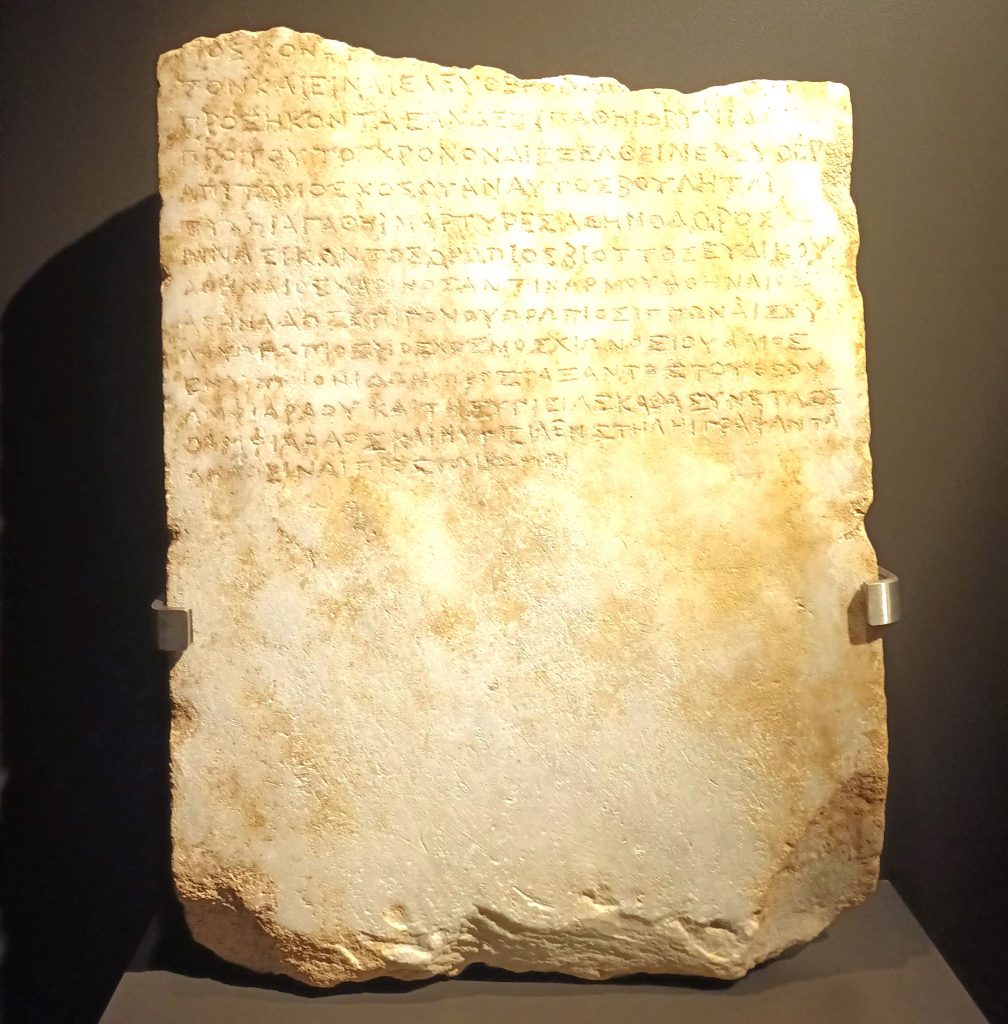

At the end of the nineteenth century, digs were undertaken here by French archaeologists from the Athens School. Southwest of the former stadium, just beside the Aegean Sea, a synagogue dating from the first century B.C.E. has been uncovered. Considered as the oldest one of the Diaspora, this synagogue was a two-room house designed for religious use. Sitting against a stone wall, a remarkable, finely worked marble armchair goes by the name of Throne of Moses. Among these ruins, an arch leads to a cistern that might have served as a mikvah.

About fifty yards or so northwest of here, right against the outer wall of the stadium, French archaeologists have uncovered another house once used as a place of worship. It was a Samaritan synagogue, sometimes referred to as the House of Agathocles and Lysimachus. This attribution comes from the discovery of a funeral stele dedicated to Serapion, a Samaritan from Knossos, found near this house. A cistern flanks this building as well.

In this area around the site, several Jewish inscriptions in Greek have been deciphered. On one of them the words “Theos Hypsistos” are engraved, the equivalent of Shaddai (“The All-Powerful” in Hebrew). In the early 1990s, another Jewish inscription was deciphered on a block of stone reused as part of a pasture wall, not far from the shore.

The synagogues are located on the northwest section of the island. A small museum houses as well several pieces unearthed during the dig.

In the late twelfth century, Jewish traveler Benjamin de Tudela encountered a lone Jew on Corfu. Three centuries later, however, Jews had become so numerous here that the Venetians, then in control of this much-coveted, strategically important Adriatic island, had them confined to ghettos.

A local Christian legend, which, strangely, spoke of Judas as a native of Corfu, made Jewish life here even more unpleasant.

The expulsion of Jews from Spain, however, led Sephardic colonies to to settle on Corfu or on the six other Ionian Islands. Thanks to prevailing revolutionary ideals, French domination from 1807 to 1815 offered Corfu’s Jews equal rights, which did not please the Orthodox Christian and Catholic majority.

When Corfu and the Ionian Islands were placed under England’s protection following the Congress of Vienna, the fate of the 4000 Jews here rapidly worsened, due to a series of discriminatory measures including the suppression of their right to vote.

The islands’ reattachment to Greece in 1864 meant a return to civil equality for the Jews, but also recurrent flare-ups of anti-Semitism. In 1891, a pogrom broke out after accusations of ritualistic crimes. An exodus of Jewish families ensued, including that of Albert Cohen, one of the most important Sephardic writers of the twentieth century.

On the eve of the Second World War, the Jewish community of Corfu consisted of only 2000 members. According to historian Mark Mazower, however, the Wehrmacht territorial commander made several attempts to stop their deportation, an extremely rare occurrence. On 9 June 1944, the order was finally given to deport them, to the overt satisfaction of the collaborationist authorities. The attitude of prominent civic and religious citizens was quite the opposite on the neighboring island of Zákinthos, where Jews were both protected and permitted to hide on the mountain-side. Only about sixty Jews remain in Corfu today.

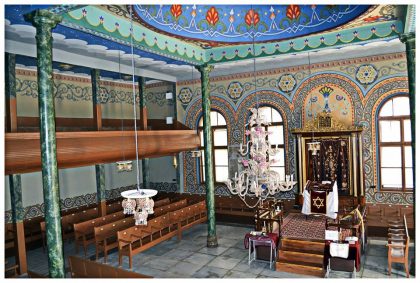

Of the four synagogues if Corfu’s old ghetto, only the Scuola Greca (Greek Temple) survived the Second World War. In Venetian style, it dates back to the seventeenth century. The prayer room is located on the second floor, with a section for women on the mezzanine. Made out of wood with a Corinthian colonnade, the tevah and aron kodesh face each other to the west and east.

The Jewish quarter, the old Venetian “ghetto” that is still called Evraiki in Greek today, stretched across the southeast section of the city, near the Venetian fortifications. It was criss-crossed with alleyways lined with faded, multistoried houses, as in Venice. The ghetto lost its urban unity due to bombardments during the Second World War.

It can be walked through starting from the Porta Réale, heading toward Solomou, Palaiologou, and Velissariou streets. Columns from a synagogue destroyed during the war were rediscovered in the early 1990s at 74 Palaiologou Street.

Ioánnina, one of the most ancient Jewish communities in Europe, still bears the deep imprint of the long Ottoman presence in Greece. At the heart of the mountainous Epirus region, Ioánnina (280 miles from Athens near the Albanian border, the two city connected by a difficult road) still harbors a small Jewish community.

Hellenized Romaniote Jews were present for over 2300 years, Ioannina being then one of its main centers. They were later joined during the Inquisition by a large contingent of Sephardim. Shut away with their traditions, indifferent to other cultures, according to a seventeenth century Turkish traveler, The Jewish community maintained a poor relationship with the Greek Orthodox majority, a situation the Turkish government did all it could to exploit. In the late eighteenth century, Ioánnina fell into the hands of a tyrant, Ali of Tebelen, an Albanian pasha of the Sublime Porte who, during a forty-year reign, carved for himself his very own fiefdom, with borders stretching as far as Albania and Macedonia. A former Napoleonic officer and Strasbourg Jew Samson Cerf Berr converted to Islam and moved to the court of Ali the Rebel; he was the nephew of Cerf Berr de Mendelsheim, a military supplier to Louis XV and overseer of the Alsatian Jewish community.

Several anti-Jewish riots broke out in Ioánnina in the late nineteenth century on the occasion of the Orthodox Easter, under pretext of accusations of ritualistic crimes. Hundreds of Jews were forced to leave the city, emigrating mostly to Jerusalem or New York. In the early twentieth century, they founded synagogues dedicated to Ioánnina in Jerusalem’s Mahane Yehuda and New York’s Lower East Side that still stand today.

On the eve of the Second World War, Jews in Ioánnina numbered just under 2000; they were all rounded up by the Nazis in March 1944.Only about a hundred survived. A monument commemorating the victims of the Holocaust has been inaugurated in 1994.

The community consists of only around fifty people today, many of whom live in a building constructed on the site of the former “new” synagogue at the border of the Kastro district and the Jewish Alliance school. Several Albanian Jews, smuggled out of that country by the Jewish Agency before the fall of the Communist regime, passed through Ioánnina in transit. Sign of hope and renewal for the Jewish community, Moses Elisaf, a Jew born in this city, was elected Mayor in 2019.

The Kahal Kadosh Yashan Synagogue can still be visited, the sole remain of the faded importance of Ioánnina’s Jewish community. Its original structure probably dates from the Byzantine era, but it was restored on different occasions. The Kahal Kadosh Hadash Synagogue (“hadash” meaning new in Hebrew, to distinguish it from the one called “yashan”, meaning old), built in the 16th century, was destroyed during the Shoah. It was located on Joseph Eliyia Street, named after a Jewish poet born in the city.

In the Kahal Kadosh Yashan’s courtyard, an ablution fountain reserved for Kohanim is located to the right, beside a well used in the tashlik ceremony; to the left, a frame used during the sukkah leans against the synagogue wall. The main door was reserved for men; a side entrance allowed women access to an upper gallery. The interior architecture, with its arches circling a central dome, reflects Ottoman influence. The synagogue, for a while used as a library, was spared during the war thanks to the intervention of the Mayor of Ioannina.

In the Its Kale (southeastern) citadel of the castle of Ioánnina is the Byzantine Museum. Here, several relics are on display: a synagogal wall hanging, a Jewish dress, and a ketubah -a calligraphic and illustrated marriage contract.

Outside the citadel, a segment of the Jewish community has regrouped in the neighboring Leonida district, bordering the lake. Stars of David are still visible on the facades of houses and wrought iron gates.

The Jewish cemetery is located in the Western part of the city, in the Agia Triada area.

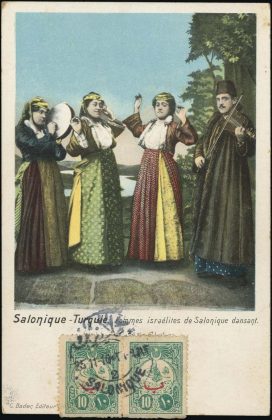

When David Ben Gurion moved to Thessaloníki to learn Turkish in 1910, he was surprised to discover a city like none found in “Eretz Israel”: The Shabbat marked the day of rest here, and even the dockworkers were Jewish. He was advised not to admit he was Ashkenazic (all the procurers were).

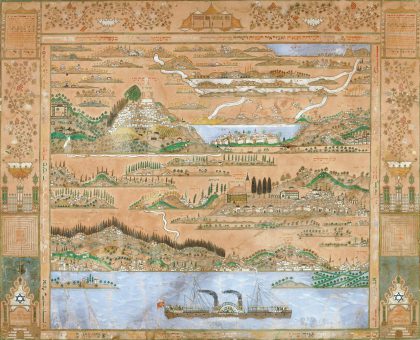

Jewish and Sephardic, Thessaloníki had been called “Mother of Israel” for over three centuries. A haven for Jews expelled from Spain, it resembled both a lost canton of Judaea and a neighborhood in Castile or Navarre. The language of the street was Judeo-Spanish (Judezmo and Ladino) while the elites here spoke French.

Not far from here, nestled at the far end of the Thermaic Gulf (Gulf of Salonika), Hellenized Jews had already converged beginning in antiquity. Saint Paul, after preaching three consecutive Shabbatim in local synagogues, had to flee under cover of night. The Romaniotes, as Jews of the Eastern Roman Empire were commonly called, suffered countless invasions here.

Sold to the Venetians, the city was conquered before Constantinople by Ottoman armies in 1430. Sephardic refugees were welcomed with tolerance in Thessaloníki by the thousands, and then by the tens of thousands. The sixteenth century was the golden age of the city’s Diaspora. Samuel Moise of Medina, the century’s most preeminent rabbi and author of a thousand responsa, summed up in a sentence the intellectual splendor of the era: “We abound in the learned and librairies; knowledge is widespread among us”.

Such blossoming was commercial as well, thanks to the Thessaloníki’s position as a stopping point between Venice and the Ottoman Empire. In 1556, a boycott of the port of Ancona was launched by Levantine Jews at the instigation of those in Thessaloníki, in protest against an auto-da-fé of twenty-five Portuguese Marranos on the order of Pope Paul IV. Moreover, the woolen garments worn by the powerful and fearful Janissaries were woven in the Jewish workshops of Thessaloníki.

In the late nineteenth century and encouraged by the Universal Jewish Alliance in Paris, philanthropic organizations, clubs of freethinkers, and political committees began to appear here. The entrance of Greek troops in 1912 was greeted with apprehension by the Jews, due to the fierce economic rivalry between the two populations. Rightly or wrongly, the Jews suspected that the great fire of 1917, which ravaged the Jewish quarter and devastated its thirty-two ancestral synagogues, had been an intentional act.

Thus began the emigration of tens of thousands of Jews to France and the United States in particular. Two events sped this exodus: the transfer of Greco-Turkish populations here as decreed by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne, which shifted the demographic balance between Greeks and Jews, a pogrom in the Jewish quarter of Campbell in 1931.

The years later, in April 1941, the first German columns marched into Thessaloníki. By the summer of 1942, all Jewish men were ordered to appear at the large Elefterias Square: for hours, they were subjected to humiliation by the Nazis before crowds of onlookers. The expropriation of the great Jewish necropolis was implemented -much to the satisfaction of the Greek authorities, according to Joseph Nehama. From March to August 1943, 46000 Jews from Thessaloníki, or 96% of the Jewish community here, were deported and exterminated in Auschwitz-Birkenau. Fewer than 1500 deportees survived. Jewish Thessaloníki had seen its final days. More than half a century later, in 1999, a monument commemorating the Shoah was put up here. At first glance, nothing recalls the “Jerusalem of the Balkans” in modern Thessaloníki, with its cold, crumbling concrete architecture. So thoroughly have their traces been erased, one might wonder if Jews had ever been present here, when they had in fact been the majority here until the 1920s.

To start your visit, you can first go to the Jewish community center of Thessaloníki.

Vestiges of prior Jewish life

Several beautiful villas once belonging to the most prominent Jewish families were miraculously spared during the frenzied real estate speculation that struck Thessaloníki during the 1950s. They were built in middle-class Belle Époque style on a boulevard once named Hamadié, now called Vassilissis Olgas (Queen Olga). Two Italian architects fought for the favors of the rich merchants who chose to settle here.

At 182 Vassilissis Olgas Boulvard sits the eclectic “Casa Bianca”, built for the Fernandez family and designed by the architect Piero Arrigoni.

More classic and luxurious, the villa once owned by Charles Allatini, Thessaloníki most important Jewish miller, was built based on plans by Viteliano Poselli, at number 198 of the same boulevard. From 1909 to 1912, Ottoman sultan Abdul Hamid II was forced to reside here after the Young Turk Revolution.

Housing the Macedonian Folklore Museum, the former Modiano family mansion is located at 65 Megas Alexandros Avenue.

Across the street from the Archaeological Museum of Stratou Avenue, a mosque was constructed in 1902 for the deunmé community, Jewish converts to Islam following the heresy of Sabbataï Zevi. The work of Poselli, the new mosque, Yeni Djami, combines turn-of-the-century Ottoman architecture with Renaissance, Baroque, and Moorish elements.

Synagogues and museums

Monastirioton is the most important still active in Thessaloníki. Built in the 1920s by Jews originating from Monastir, a city located in current Macedonia, it was used by the Red Cross during the Second World War. The structure was copied exactly from classical Sephardic design, the aron kodesh to the east, and the chest of the bimah to the west.

Another synagogue, Yad Lezikaron was reconstructed in 1984 inside a modern building on the Herakleios Street. The arch comes from the former Kal Sarfati, the French synagogue, while the bimah originates from the Baron Hirsch Synagogue, which bears the name of the famous Jewish philanthropist.

The museum of History of the Jews of Thessaloníki is located in what was once a Jewish bank. Its permanent exhibition explores the life and culture of the Sephardic community of the city since the fifteenth century.

The Yad Lezikaron Synagogue and the the museum of History of the Jews of Thessaloníki are located in the district around the Modiano market, named after the large Jewish family that originated in Livorno. All sorts of trades were practiced by Jews here, as much in the metal and glass-roofed market as in the surrounding neighborhood. Thessaloníki’s oldest ad largest bookstore, Molho Solomon, is located in a street parallel to Herakleion Street. A meeting place for the cultural elite, this bookstore belonged to the Molho family, who were saved during the war by a Greek Orthodox family.

The necropolis and cemetery

In the exact spot of the ancient Jewish necropolis now stands Aristotelous University. The huge cemetery, where the remains of twenty generations once lay, was destroyed by the Nazis to the great satisfaction of the local Greek authorities; crowds of pillagers then descended on the site, convinced that the Jews, already packed in ghettos, had hidden their treasures there. The tombstones were later used in the construction of school playgrounds, university stairwells, sidewalk gutters, and even barrack latrines; at times, the funerary inscriptions were not even removed and still can be read today. The modern cemetery, where a few ancient gravestones have been gathered, is located on Karaoli Demetriou Street, across the street from the AGNO factory.

3,2,1… go! Set off on a marathon walk through time, 2500 years to be precise, to discover the monuments of Athens and its Jewish cultural heritage.

Starting with the Panathenaic Stadium. An ancient stadium dating back to 330 BC, it was renovated in 1896 to host the first Olympic Games of the modern era, with 28,400 spectators cheering the athletes.

Then, cross over. Either to the right, the beautiful National Gardens, with Roman ruins, a wide variety of botanical plants and a small zoo.

Or to the left, the ruins of the Olympion and the temple of Chronos and Rhea.

As you move back and forth between modern times and antiquity, after Hadrian’s Arch you come across the statue of the great actress Melina Mercouri, in front of the Onassis Foundation.

If you turn right, you will come across the Jewish Museum of Greece, which spans several floors and tells the story of Greece’s long Jewish history.

After facing the former royal garden for twenty years, the Jewish Museum of Greece has moved to a beautifully renovated neo-classical house in Plaka. Important collections of documents, costumes and objects of worship from the Romaniote and Sephardic communities are displayed here by theme and by level.

On the ground floor, the interior of the former Romaniote synagogue in Patras has been reconstructed. Under the new name of Alkabetz, it was consecrated by the Chief Rabbi of France, Samuel Sirat, in 1984. The first level of the exhibition features a cycle of Jewish festivals, historical documents on Jewish communities in Greece, traditional costumes and religious and domestic objects.

This is followed by the various migrations to the region at different times. But also the participation of Jews in the great events of history, from the country’s independence to the calls to the flag, but also the dark hours of the Shoah, with a tribute to the Righteous of Greece.

A new exhibition allows visitors to see some very rare and ancient objects.

Before heading to the Agora, in the hope of making other major archaeological discoveries, you can visit the Acropolis and the other mythical and mythological sites that surround it. In particular, the Theatre of Dionysus, where this art form was invented in the 6th century BC.

A bit like the Masada climb, you’ll gradually make your way up the most symbolic site in Athens, dedicated to the goddess Athena and featuring the ruins of various temples and theatres.

On the way down, the pretty Plaka district welcomes you with its small houses and tourist-friendly restaurants. There are also other ancient ruins, which you can visit with a combined ticket for the Acropolis and the Agora.

The Agora awaits you with an explanatory map of the various sites at the entrance. On the left is an interesting museum of ancient artefacts.

Opposite you is a large park with ruins, meeting places where Socrates probably wandered, just a few hundred metres from where his rival Sophocles triumphed on the stone stages of the ancient theatres. Contemporary statues of Socrates and Confucius side by side allow visitors to imagine what the dialectical richness of such a meeting might have been.

Finally, on your right is the temple of Hephaestheion. Leaving the Agora, 400 metres to the left are the two synagogues of Athens. In an area that has become fashionable, with a wealth of bars, they face each other on Medioni street.

Built at the turn of the century, the older synagogue, Etz Hayim, was also nicknamed ‘Ioanniotiki’ because it was frequented by Jews from Ioannina. It is only open on major holidays.

The other synagogue, Beth Shalom, is a neoclassical marble building built in the 1930s.

Less than 100 metres away, the Holocaust Memorial in the shape of a broken Magen David was inaugurated in 2010, in memory of the 65,000 Greek Jews deported and murdered. After this long visit, all that’s left for you to do is stroll along the Athenian flea market and shopping streets on your right.

Other important places to visit to learn about the city’s history are the Athens Archaeological Museum and Mount Lycabetta, for those who are not afraid of heights.

The Jewish cemetery in Athens is close to the Panathenaic stadium.

Between the two is the ancient cemetery of Athens, which, like the Père Lachaise cemetery in Paris, is an important place for understanding the historical development of the city and the great people who built it.

During the months when the weather is fine, which is the majority of the time in the city, don’t hesitate to take a taxi, which is relatively cheap in the city compared with other European cities and compared with the price between Athens airport and the city centre, to go to the beach, which is a 15-minute drive to the west (without traffic jams) south of the mythical port of Piraeus, where you can meet Poseidon.

History of the Jews of Athens

There is evidence of a Jewish presence in Athens, as in Alexandria, during the Hellenistic period. There is no doubt that Paul of Tarsus, as elsewhere in Greece, went to Athenian synagogues to preach. One of them, dating from the 2nd century AD, seems to have been identified on the Agora, at the foot of the Acropolis and its Parthenon.

However, for several centuries, there was no evidence of the presence of Jews in Athens. The ancient city was no more than a modest market town of 4,500 inhabitants when it was proclaimed the capital in 1833.

The Jews returned in the wake of the first Bavarian monarchy. After his enthronement, the monarch Othon confided to a group of Jewish notables that ‘he considered his kingdom blessed and honoured to contain within its bosom the biblical race of Israel’. This laudable declaration of principle did not prevent outbreaks of popular anti-Semitism.

After intervening to stop a traditional anti-Jewish ceremony, the ‘Judas hunt’, a Jewish businessman and British citizen, David Pacifico, had his warehouses ransacked in the middle of the 19th century. England decided to intervene on his behalf, even initiating a blockade of the Greek coast in order to obtain substantial compensation.

Although far from the size of the Jewish community in Thessaloniki, relations between Athenian Jews and the authorities and the population were much better. The German takeover of Athens in 1943 marked the beginning of the terror. The active resistance of the authorities, in particular police chief Anghelos Evert and Orthodox archbishop Mgr Damaskinos, was exemplary.

While there were still almost 5,000 Athenian Jews after the Shoah, there are only 3,000 today, representing half of all Greek Jews.

Interview with the leaders of the Jewish Community of Athens

Jguideeurope: How is the Jewish community organized and which changes in its cultural heritage (new places, renovations…) have occured?

JCA: The Jewish Community of Athens, the largest Jewish community in Greece, is a vibrant and dynamic community consisting of over 3.500 members. Its main purposes are philanthropic, cultural, and educational. The Jewish Community of Athens is managed by a 13-member Community Council which is elected by an elected 50-member General Assembly; both groups preside for a three-year term. There are many special Committees, composed of volunteers (over 150), who help significantly in the management of the Community through offering their valuable time and services. All the above is supported by a small professional team.

The Community operates two Synagogues, a fully compatible Mikveh (ritual bath), the Community Center — which hosts a variety of events — and the Jewish Cemetery. An important part of our Community is the Lauder Athens Jewish Community School which consists of a Preschool and Primary Education program. The school’s attendance is more than 100 children per year. The existence of a remarkable social solidarity system for the elderly, the sick, the needy or those in general need, makes our Community very proud.

Within the past years, both of our Synagogues have been renovated. The Beth Shalom is a Sephardic synagogue, built in 1935 and renovated in the 1970s’. It is located right across the street from the Ets Hayim synagogue and can accommodate 500 people. It hosts all bar-mitzvahs and bat-mitzvahs, weddings, memorial services and visits. The Ets Hayim is a Romaniote synagogue, built in 1904 and renovated in 2006. It can accommodate 400 people and is mostly used during the High Holidays, when Beth Shalom synagogue attendance is high. On the ground floor are the Administration offices of the JCA.

Located next to the Synagogues is the Holocaust Memorial. It was inaugurated in 2010 to honor the memory of the 59,000 Greek Jews killed by the Nazis during WWII. The monument depicts a shattered Yellow Star of David, symbolizing the heavy loss to the Jews in Greece. The separated triangles or points of the star are scattered over small irregular distances pointing in the direction of the corresponding Jewish communities carved by name onto the marble. The center of the star is kept whole to symbolize that the core remained to continue the historical course of Greek Judaism.

In the courtyard of Beth Shalom Synagogue is the Greek Righteous Among the Nations Memorial inaugurated in 2016. It pays tribute to the 357 heroes of the German Occupation and their Christian compatriots, who saved Jews by risking their life and the lives of their families.

Who are the contemporary Jewish culture figures in Athens and are there regular events organized to promote the Jewish heritage?

Among the members of the Jewish Community of Athens there are many contemporary Jewish culture figures such as writers, singers, musicians, actors and visual artists. Please find below some of them who contribute by their field of interest to the Jewish life in Athens and in Greece through their art.

Mr. Aris Emmanouil is involved in many communal activities, both as a professional and as a volunteer, who is also the author of an album for the Lauder Athens Jewish Community School on the completion of 54 years of its operation and a Glossary of Hebrew Terms and Names that is given to our members. The book is also distributed to all the girls and boys that have been celebrating their Bar and Bat Mitzvahs. The former Rabbi of Athens, Isaac Mizan has published an extensive study of Shulchan Arouch. His book was distributed free of charge to all members of our Community and granted the rights to the book to the Jewish Museum of Greece. Other distinguished members of our Community, Mrs. Kelly Matathia Covo is a children’s book writer and has been awarded in the field of graphic design, where one of her books has an indirect hint for the Holocaust and Mr. Iosif Ventura, a poet and the only survivor of the Jews of the Island of Crete who has published – among others – the book TANAIS including poets, which refers to the drama of the extermination of the Jews living in Greece by the German occupiers but also more generally to the historical event of the extermination of the Jews of Europe in the Nazi concentration camps. Following, Mrs. Artemis Alcalay is an artist of modern art and has exhibited her art about Holocaust in the year 2018 on the International Holocaust Remembrance Day.

For a more realistic aspect on her art, she talked to many Holocaust survivors. Mrs. Alcalay has also launched a bilingual (Greek and English) website, dedicated to the “Greek Jews Holocaust Survivors”, which includes material from her interviews with Holocaust survivors and publications, exhibitions and project presentations. Additionally, Mrs. Odette Varon-Vassard, is a historian and a professor and has given multiple lectures on the field of Holocaust. Mr. Michel Fais, a writer and a screenwriter, with books that have been translated to languages such as in English,

Spanish and French and short stories published abroad. The actor and writer Mr. Alberto Eskenazy and also Mr. Alberto Fais, who is an actor, and presented the ceremony of the Memorial Holocaust Remembrance Day that the Community along with the Municipality has organized this year and volunteers to any event his services are relevant. Last but not least, we would like to mention the Kapon Publications and the Gavriilidis Publications, whose variety of published books include the history of Greek Jews, especially during Holocaust and World War II, hence contributing to the conservation and the transmission of the memory.

Also, professionals from JCA and members, such as the Director of JCA, the Director of JCC and others, who are musicians and singers, always contribute with their knowledges on music to various events by promoting the Sephardic and the Romaniote routs of Jews in Greece. We are happy that our Community is surrounded by many artists who are always by our side to offer their services, thus enriching the cultural side of the Jewish life in Athens.

Sumptuous and decadent, immense and frenetic, Istanbul is “the world in one city”, as it is often described by Western travelers overwhelmed by the city’s splendor. The skyline of Istanbul is punctuated by hundreds of minarets, majestic onion domes, and bell towers. “An aged hand covered with rings held out toward Europe”, according to Jean Cocteau, the great city of Bosphorus mixes the heritage of Byzantium and the Ottoman Empire, of the Orient and Europe. In this extraordinary mixture of the vestiges of centuries, the Jewish presence can appear quite discreet. There are hardly more than 20000 Jews in Turkey today, a drop in the bucket compared to the 12 million inhabitants of Istanbul. The Jews, like all the inhabitants with old roots here, are drowned out by the mass of Anatolian immigrants that have streamed into the city in the last thirty years. More often than not, Istanbul’s Jews speak Turkish among themselves, even if most know French. Only the very elderly remember Ladino, their old language to which the Hebrew weekly Shalom (circulation of 3500) still dedicates one or two pages in each issue. The number of kosher restaurant can be counted on one hand and are often located in hotels for Jewish tourists passing through. Of the sixteen synagogues still in existence, only a handful are active.

Although Turkish Judaism and its monuments and cemeteries were spared the Shoah and the devastation of Nazism, real estate speculation and grand-scale urban renewal projects have destroyed a number of memorials. A highway passes through the middle of the old cemetery of Hasköy atop the Golden Horn. The sumptuous tomb of the Camondo family is thus surrounded by the roar of traffic. Jewish Istanbul still exists, however. One sees it in the summer when Jewish families, most now dispersed in different parts of the city, run into each other at Büyükada (Prinkipo), a traditional vacation spot on the largest of the Princes Islands in the Sea of Marmara. Prosperous merchants, businessmen, famous industrialists, and reputable doctors, Istanbul’s Jews have almost all forsaken the former judería (Jewish quarter) of Balat, Hasköy, Kuzgunçuk (on the Asian side), and even the European old town next to Galata and Beyoglu in order to settle in the new residential neighborhoods. Still, fascinating vestiges of Istanbul’s secular pluralism remain. Less visited by tourists than other European cities, Istanbul’s monuments are no less moving.

Visitinh Jewish Istanbul merits at least two days. It is necessary to contact the Foundation for the Rabbinate’s Synagogues at least twenty-four hours in advance for reasons of security and because many places of worship are closed. We have divided the tour of Istanbul’s Jewish heritage into four large zones.

Synagogues outside Istanbul

There are synagogues in several Turkish cities beyond Istanbul. Although in ruin, some retain their original splendor, as for example the synagogue at Edirne, a large city on the Bulgarian border where the Jewish community was particularly influential.

In southwestern Anatolia, in the impressive remains of the Lydian city of Sardes (fifty-six miles from Izmir), you can explore the ruins of an ancient synagogue dating from the third century. Sardes was the former capital of King Croesus, who was defeated by the Romans in 133 B.C.E.

The wealthy port of Izmir (formerly Smyrna), a bustling center of Jewish life during the Ottoman Empire, still has a half dozen interesting synagogues, of which the beautiful Giveret (Senoria) is one. Constructed in the sixteenth century under the sponsorship, it is said, of Dona Gracia Nassi, the aunt of the famous Joseph Nassi, it was remodeled following a fire in 1841. The Shalom Synagogue and the richly decorated Bikour Holim Synagogue are also noteworthy. In the latter, be sure to admire the niche ornamented with magnificent paintings above the tevah.

Twenty-five hundred members strong before the war, the Jewish community of Ruse, on the banks of the Danube, was reduced to barely 200 people after mass departures to Israel in the late 1940s.

Since the fall of Communism, however, the Shalom organization has attempted to revitalize and return the Ashkenazic Synagogue here to service, the last one built in Bulgaria, in 1927. The Sephardic Synagogue, which dates from the late nineteenth century, is no longer active. Both buildings are closed to the public.

It was in Ruse in 1905 that Nobel Prize-winning writer Elias Canetti was born. He lived at number 13 on Gurko Street, where the former Sephardic Synagogue is located.

The synagogue here has been transformed into an art gallery.

Built at the turn of the century following plans of the Italian architect Ricardo Toscani, during the 1960s it was completely remade into an exhibition space for some 2500 works by contemporary Bulgarian painters, as well as for a collection of old icons.

A terrorist attack was carried out against Israeli tourists in Burgas in 2012.

The Zion Synagogue dates from the nineteenth century.

It is still active, but only a small minority of 300 to 400 Jewish inhabitants are still practicing.

Restored in 2003, the synagogue is adorned with a delightful Venetian-glass chandelier and a richly decorated dome.

In the surrounding area, traces of what was once a sizable Jewish quarter can still be found today. This includes Stars of David which are engraved on certain gates.

The Jewish presence in Plovdiv probably dates from the 3rd century, when the oldest synagogue in the country was built. 3000 Jews lived in Plovdiv in 1912. This figure rose to more than 6000 on the eve of the Second World War.

A monument was built by the Jewish community of Plovdiv to thank the city for its courage during the Second World War. Many intercultural events are celebrated and shared in Plovdiv.

Some of the richest Sephardic families in Europe made their fortune in the small city of Samokov, located about thirty-seven miles south of Sofia. A branch of the Apollo family, which originated in Vienna, founded a veritable empire here, with ventures in metallurgy, tanning, weaving, banking, and real estate.

The beautiful synagogue, today a national historic monument, along with a number of other public works (bridges, public fountains, etc.) were built by the Arieh family.

Acknowledgment or love

The Arieh family, after settling for a while in Vienna, had to leave the Hapsburg capital one day because the wife of tolerant Joseph II (1765-90) had set their sights on one of the clan’s most handsome, eligible bachelors. The Ariehs first moved to Vidin, then Sofia, and finally Samokov.

Midhat Pasha, a reformist pasha of the 1860s, one day told an assembly of the city’s Jews that he knew of no people “in either Sofia, Kyustendil, of Dupnitsa, whether they be Turks, Bulgarians, or Jews, who are as intelligent as the Ariehs.”

Jews reached Sofia during the first centuries C.E., the era of Roman domination. Ashkenazic Jews emigrating from Hungary and Bavaria were joined in the fifteenth century by Sephardic Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition.

Until 1890, they lived in a sort of ghetto, which was later torn down by the new capital of independent Bulgaria.

Although one section of the city is still called the “Jewish quarter”, nothing along its main street remains today of the many shops with signs which are blending all kinds of languages: Spanish, Hebrew, and French.

Opened in 1909, the Grand Sephardic Synagogue still looms above the heart of Sofia. The third most important temple in Europe besides the synagogue in Budapest and Amsterdam, this synagogue is best described in stylistic terms as both Byzantine and Hispano-Moorish; it strongly resembles the famous Viennese synagogue on Leopoldsgasse destroyed by the Nazis.

Its construction was entrusted to Austrian architect Friedrich Grünanger. Seriously damaged during an Allied air bombardment in 1944, it never received any significant restoration under Communist regime. Important work has been accomplished in recent years, however, thanks to donations from Israel.

Open for worship, it is visited by only fifty or so of the faithful, though it was designed to accomodate thirty times that number.

Adjacent to the synagogue, a small museum is dedicated to the last-minute rescue of the Bulgarian Jewish community during the Second World War.

The Jewish cemetery, dating to the end of the nineteenth century, is still in use.

Twice a week, you can join a guided tour exploring the traces of the Jewish community of Sofia: https://freesofiatour.com/sofia-jewish-tour/