Ostend is a seaside town that has been very popular with British holidaymakers for centuries, as James Joyce, for example, testified. But also for the Belgian working class. The Ostend painter James Ensor depicts the characters and landscapes of the city in his work. It was also the birthplace of the Belgian singer Arno.

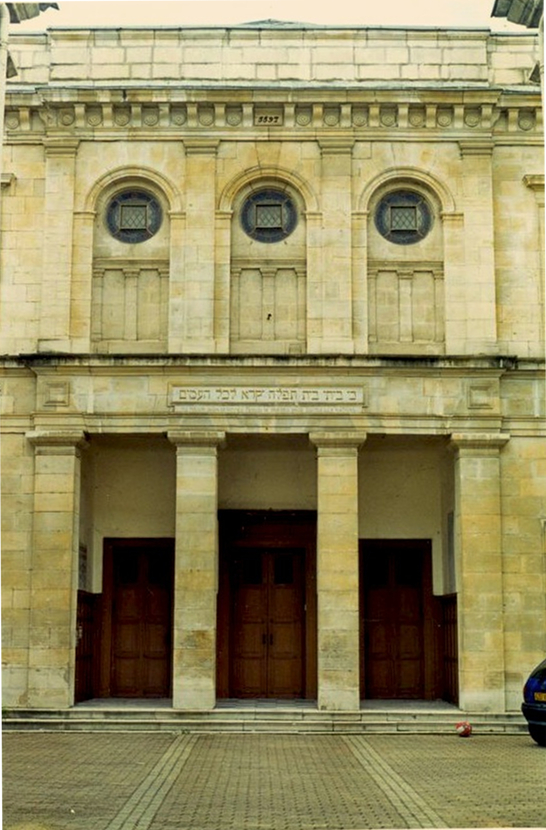

The synagogue of the handsome coastal town of Ostend becomes busy in the summer. It was built partly with the help of rich financiers. At one time, as many as 300 families came to pray here. Among the famous Jewish figures who stayed in Ostend were Marc Chagall and Albert Einstein.

The Jewish presence in Ostend has been noted since the 16th century, but it was especially consolidated at the turn of the 19th century. After the independence of the country, the Belgian authorities recognised the Jewish communities as early as 1831. Nevertheless, the community of Ostend did not benefit from this recognition, probably because of its small size.

The coastal town attracted many tourists and Belgians looking for a better life, which also motivated some Jews. Thus, at the end of the 19th century, some 300 Jewish families stayed there during the summer period. About 100 Jews lived there. On 10 December 1910, the Ostend Jewish community, recognised as such by the authorities since 1904, obtained a permit to build a synagogue. It was designed by the architect Joseph De Lange and inaugurated on 29 August 1911. It is in Romanesque style, inspired by the synagogues of Frankfurt, Stuttgart and Strasbourg, and is located in Place Philippe de Maastricht. It can accommodate up to 600 people. This synagogue is unusual in that it is little frequented by Jews. Its beauty and harmonious proportions have made it a popular tourist attraction. Indeed, it is supported by contributions from non-Jews. It is the only synagogue in west Flanders to have a facade giving onto the street.

The Jewish population of Ostend doubled during the interwar period. The Shoah claimed many victims among the Ostend Jews. Nevertheless, the community was rebuilt after the war, and the synagogue is still in operation.

Sources : Consistoire, Politique et Religion : le Consistoire Central de Belgique au XIXe siècle

Ghent is a city known, like Liège, for its student life but also as an important cultural centre, its port, and its ancient textile activity.

The Jewish presence in Ghent seems to date back to the 8th century, according to some sources. The Jews were expelled from the city in 1125 but were allowed to settle again in the following century. In the following century, they were allowed to settle again, only to be expelled again as a result of the Black Death and the false accusations that accompanied it.

Their timid return began in the 18th century. In 1756, only one Jew from Ghent was recorded as working as a jeweller. The Jewish population increased under French rule at the end of the century. In 1817, there were 107 Ghent Jews, most of them from the Netherlands. The Dutch had a synagogue in the city, but it was under the control of the Brussels Synagogue. The Jodenstraatje, the ‘Jewish alley’, was designated at that time, and the community obtained a site for a Jewish cemetery.

In 1875 there were 180 Jews in Ghent, and on the eve of the Second World War the Jewish population of Ghent was 300, an increase due to the arrival of Jewish students from Eastern Europe enrolled at the University of Ghent, in particular at the Polytechnic.

Following expulsions and deportations, only 150 remained at the end of the war, largely saved by the solidarity of their non-Jewish fellow citizens. Israeli students were integrated into Ghent life in the post-war years. For about twenty years, the congregation met in a refurbished synagogue. In 1995, however, the building became too dilapidated. Since then, the Ghent Jews have been meeting in a room lent by a Protestant Centre.

The Michael Lustig Monument , named after the former Ghent rabbi, commemorates those murdered during the Holocaust. It is in the form of a spinning top on which the names of the victims are engraved.

In September 2025, the Munich Philharmonic was denied a festival in Belgium because of its Israeli conductor. This ‘cultural boycott’ was denounced by the German government. The Flanders Festival in Ghent claimed it could not ‘provide sufficient clarity’ on Lahav Shani’s position regarding the Israeli government. In solidarity with this heinous act, Belgian Prime Minister Bart de Wever attended a Munich Philharmonic concert in Germany a few days later.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, Consistoire, Politique et Religion : le Consistoire Central de Belgique au XIXe siècle

The last real shtetl in western Europe, Antwerp is known for its Orthodox Jews and its diamonds industry. Barely twenty years ago, approximately 80% of Antwerp’s Jewish population used to make a living from the diamond industry. More than half of the world production of diamonds passed through these few streets near Centraal Station. The diamond centers, which can be visited, also served as meeting places where ongoing debate took place over the social, cultural, and political issues affecting the Jewish community.

The story of the Jews of Antwerp seems like taken out of a novel. With its peak, golden ages, but also the impact of WWII and the economical crises.

Also baptized the “Jerusalem of the North” for its ashkenazi synagogues and yeshivot, Antwerp’s Jewish community was nevertheless founded by Sephardim in 1526, Marranos from Portugal. Belgium having through the centuries been at the center of its powerful neighbors’ wars, Jewish life varried according to the willingess of the empires ruling the city, going back and forth from tolerance, expulsion and civil rights inclusion. The attachement of Flanders to the Netherlands before Belgian’s independence in 1830 and the development of Amsterdam and Antwerp’s ports encouraged a stronger link to Dutch ashkenazi Jews.

From 151 Jews in 1829, the city was the home of more than 35 000 a century later. This was mostly the result of the arrival of Eastern European Jews, who on their way yo the port of Antwerp, hoping to embark they discovered the joy of Belgian life and most of them decided to stay. The Red Star Line Museum tells the story of the 2 million who embarked on their way accross the Atlantic Ocean.

The Jews took an important part in the diamond industry’s boom along the 20th century, participating in all parts of the trade, as factory workers, salesmen, inventors, jewellers… So much so that during WWII, Cuba welcomed Jewish refugees from Antwerp who opened a diamond cutting factory.

The documentary Cuba’s Forgotten Jewels by Judy Kreith and Robin Truesdale tells the fabulous story of hundreds of Antwerp Jews who were allowed to move to Havana. But first they have to outwit the traps on the way to the exodus, through France, Spain and Portugal to get on board.

The golden ages concern two generations. One after the war and then their children in the 70s and 80s. During that era, kids attended Jewish schools in big numbers, actually more than in any other city in the world apart from the ones in Israel. Schools who weren’t only yeshivot. On the contrary, Tachkemoni, a mainstream Jewish school which at its peak welcomed about a thousand students, strictly follows the Belgian curriculum and offers on top of that a very high level of Jewish studies. The Jesode Hatora is the other main historical Jewish school in Antwerp, which has grown significantly in recent decades. The Yavne school was built in the 1980s to cater for the Mizrahi community.

Jan Maes, a former director of Tachkemoni, is conducting now a remarkable task in finding the names and photographs of victims of the Holocaust still not fully identified. A monument now stands in Antwerpen, honoring the memory of the Holocaust victims.

Apart from the gatherings during the Holy days at the synagogue and in the diamond district, Jews from Antwerp have lived mostly in two different entities. The orthodox Community on one side and on the other the rest of the Jews, ranging from atheists to the disciples of the Rav Kook, who all shared many moments. At school, but also in the youth movements (Hashomer Hatzair, Hanoar Hatzioni and Bne Akiva) and the sports club Maccabi.

Maccabi enjoyed its glory days in multiple eras and sports. Its football team in the 30s (one of its best players keeping the surname Arsenal, a team he cherished, even at work) which remained a Division 4 team until the 1990s, its water polo team in the 50s – 60s and its tennis club which produced two national champions.

The Romi Goldmuntz center hosted cultural and social activities for many decades after the war, welcoming most weddings and bar/bat mitsvoth. As most of the schools and synagogues, it was located in the heart of Antwerp, on the Nerviersstraat, near the Belgielei avenue. This building, due to the diversity of activities, has welcomed all generations. The evening room, where galas and parades were also held, was on the ground floor, behind a café-bar and a room where bridge lessons were given, one of the favorite activities of the Jewish community in Antwerp. On the 1st floor, a restaurant which welcomed in particular many schoolchildren at noon and a sports hall where the ping pong tables were set up at noon as entertainment after the meal and before classes resumed. And next to it a room for karate and judo lessons. On the upper floors, a children’s playroom, a theater, a library and an exhibition hall. And even in the basement a nightclub which was also used for teens celebrating their bat mitzvah and bar mitzvah in a less formal setting than the great room.

The diamond industry evolved a lot during the last twenty years, with the disappearance of the diamond cutting factories and the different specializations now taking over in the sector. This evolution motivated many Jews to work in other fields or choose other destinations.

If the Romi Goldmuntz center is now closed, as are cultural landmarks such as the Kahane bookstore near the train station, youth movements and schools still play an important part of the Jewish life in Antwerp. As do the orthodox institutions. The recent generations have provided national figures in many field, especially theater.

The synagogues

There are six Ashkenazic rite synagogues in Antwerp. The biggest is Romi Goldmuntz . The Shromei ha-Das Synagogue, with over 6000 members, and the Israelitische Gemeente van Antwerpen, founded in 1904, represent the city’s Jewish community.

Next come the more Orthodox communities, united under the Mahzikia organization . This includes all the current in the Hasidic movement, such as the Satmar, the Gourer, and the Sanzer. In Europe, only London’s Stamford Hill can offer comparable diversity.

The Sephardim meet in their synagogue near the Diamond Exchange . Antwerp’s Portuguese-rite Israelite Synagogue includes some 300 families and has been swollen by the arrival of numerous Israelis. A plaque on an outside wall commemorates the victims of the 1981 terrorist attack, which was claimed by a Palestinian group.

The Kosher pleasures of Yiddish Town

Yiddish Town, also known as “Pelikaan”, from the name of one of its main streets, is located around Centraal Station. Here, at the back of the houses or in arcades, you can find various restaurants and delicatessens usually bearing the name of the family owners.

Walking around here, one would not guess that access to the Dresdner is through the butcher shop. This leads to a galleried yard at the back of which stands a small modern restaurant. The cloakroom, where long traditional coats, black hats, and prayer books are left by the tables, gives an idea of the place’s great orthodoxy.

And of course Antwerp’s famous delicatessen, Hoffy’s , opened in 1986, offering typical Ashkenazi flavours. And if you have the pleasure of visiting the main Diamond Club, you can sample some very tasty dishes in its restaurant, a veritable institution founded by the caterer Sam, who decorated banquets for all kinds of festivities with his dishes for decades.

Antwerp has a large number of butcher shops, bakeries, and stores specializing in typical Jewish products. Be sure to stock up some cakes and pastries at Kleinblatt and Steinmetz .

Last but certainly not least, another culinary reference close to Tachkemoni is Beni falafel , where young schoolchildren have been flocking for generations to try falafel, and nostalgics still talk about the iron-inflated pitoth in the 1980s.

Outside of this area, another stop is necessary. A walk through the area around the sumptuous Royal Museum of Fine Arts will also take you to the sublime Dutch synagogue . Built by the architect Joseph Hertogs in 1893, it often hosts large ceremonies. Closed for eight years due to renovation, it has been open to the public again since autumn 2022.

While the Orthodox population mainly lives in this district, other Jews have migrated since the same years to the southern districts of Berchem, Wilrijk and especially Edegem. Edegem has been home to the Chai Center , which houses a synagogue and a very active cultural centre.

A memorial was erected in 1983 in the former transit and deportation camp in the northeastern Netherlands. It depicts two broken railway tracks, a symbol of the dead trains. The monument was designed by the Jewish artist Ralph Prins, who was deported from this camp as an infant.

In addition to the monument, the Dutch government added in 1992 a paving of 104,000 bricks (corresponding to the number of Dutch Jews assassinated) in the shape of a map of the Netherlands. Each brick bears a Star of David. In the museum, which opened in 1983, there is a list of the Dutch casualties who were buried in unmarked graves during the war.

The monumental Ashkenazic Synagogue in The Hague was sold to the municipality, which put it at the disposal of a congregation of Turkish Muslims. It has since become the Al Aqsa Mosque.

The Ashkenazic community in The Hague then acquired a former Protestant church in the Bezuidenhout quarter and transformed it into a synagogue and community center .

Because the maintenance costs were too expensive, however, the synagogue was turned into an apartment building. Today only the first floor serves as a synagogue and community center.

The first Jewish burials in the recently restored Scheveningseweg cemetery occured around 1700.

There is a statue of Baruch Spinoza in front of the house where he spent the latter part of his life and where he wrote his most important philosophical works after being banished from the Jewish community for what were considered “heretical opinions”.

In 1673, he was offered the chair of philosophy at the University of Heidelberg on the condition that he cease his attacks on organized religion, but he declined the offer, preferring to continue to study in his retirement.

Interview with Marie-Thérèse Daniëls-Dirven, in charge of the Spinoza House in The Hague.

Jguideeurope: Where do most visitors come from? Have you witnessed different motives according to country of origin?

Marie-Thérèse Daniëls-Dirven: Since July 2018, Domus Spinozana is open exclusively on Monday afternoons. Most visitors come out of a prior interest in Spinoza. Some are foreign students resident in The Hague or students from abroad. But there are also passing tourists, both young and old.

Some highly interested foreign visitors plan their trip to The Netherlands well in advance. They want to see everything related to Spinoza. For these visitors, we are happy to make an appointment on another day than Monday if this suits them better.

We receive visitors from all over the world: Korea, Japan, China… It is difficult to say whether motives vary according to country of origin. What one can say with certainty is that the great diversity of visitors shows how Spinoza, with his encouragement to think for oneself and his plea for unlimited freedom of expression inspires people from all nationalities.

How is Spinoza’s heritage kept and upgraded?

Spinoza’s house, known as Domus Spinozana, was built in 1646 by Jan van Goyen, a well-known landscape painter of the time. Some years later the house was occupied by Jan Steen and his wife Grietje, the daughter of Jan van Goyen. Hendrik van der Spyck was the landlord of Spinoza.

Spinoza lived in the attic of the house during the last 7 years of his life and died here on 21st February 1677, at the age of 44. It was in this house that Spinoza completed in 1675 his text, Ethics, which was published after his death.

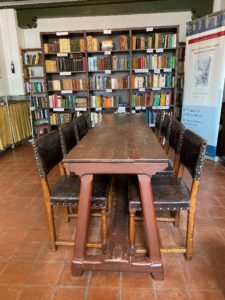

At present, only the reading room on the ground floor is open to the public on Monday afternoons from 14.00 to 16.00. The space is designed for scholars and students. Here one can consult a book, speak to the custodian or simply breathe in the atmosphere of this historic building.

Our website, www.spinozahuis.nl includes a virtual Spinoza tour of The Hague.

The Jewish presence in Belfast appears to date back to the mid-19th century, with the arrival of German Jewish merchants. The first synagogue in Belfast was built in 1871 on Great Victoria Street. A second synagogue was built in 1904 on Annesley Street. Daniel Joseph Jaffe, the founder of the community, was honoured with a fountain named after him. His son, Otto Jaffe, was Mayor of Belfast. Belfast’s Jewish community now numbers around one hundred people.

Belfast’s synagogue holds regular Friday evening services.

The cemetery of Falls Road, a few miles north of Belfast, has one of the oldest Jewish tombs in Northern Ireland, a big granit obelisk in memory of Daniel Joseph Jaffe. Sadly, the monument has been neglected and is regularly covered with graffiti.

Limerick’s small Jewish community (170 people) disappeared in 1904 after the only pogrom in Irish history- a pogrom with zero victims. The small Jewish cemetery of Kilmurray at Newcastle, County Limerick, has been restored and its six tombstones are preserved.

The Jewish presence in Cork appears to date back to the 18th century. However, the community was formed mainly at the end of the 19th century, notably with the arrival of Lithuanian Jews. At the beginning of the following century, the community numbered almost 500. Following the decline of this community, the synagogue closed its doors in 2016. A new congregation has recently been established.

The Shalom Park opened in 1989 on the site of the old “Jewstown”. This was the quarter where James Joyce’s father was born. Offices were held at a local synagogue until recently. The worshipers now pray at the Dublin synagogue.

York’s Jewish community was the victim of the bloodiest outbreaks of anti-semitism in the twelfth century. In those days the Jews were well-established alongside the merchant classes, to whom they provided financial services.

However, following the death of Henry II, the protector of the Jews, and the coronation of Richard I, “the Lionheart”, anti-Jewish riots struck.

The slaugther of Clifford’s Tower

On 16 March 1190, while the king was away on a crusade, the barons in debt to the Jewish moneylenders attacked Clifford’s Tower, where the moneylenders had taken refuge. The Jews were trapped; some committed suicide and the rest were slaughtered.

Today, a stone edifice stands on the site of the old wooden castle, and visitors to the monument can learn about the terrible massacre.

The Aldwark Synagogue served York’s Jewish community from 1886 until 1975. However, at that point, the community declined and became affiliated with Leeds United Hebrew Congregation for the purposes of religious services and burial rights. However, according to the 2001 census, the Jewish population of the city numbered nearly 200. A new liberal community was established in York in 2014.

In recent years, Leeds, one of the main economic centres in England after London and a place with a rich cultural life, has attracted many families, also thanks to a pleasant lifestyle that is relatively safer than in many cities.

A new lease of life embodied by the very active MAZCC community centre. The centre brings different generations together around social and educational services and family and cultural events. With a particular focus on youth programmes, including training for future community leaders.

There are less than 10,000 Jews living in the Yorkshire town of Leeds. They began arriving around 1840 and, in increasing numbers, between 1881 and 1905 as a result of persecution in Russia. The town had a flourishing wool industry and, in 1885, was the scene of the first spontaneous strike by Jewish workers. The inhabitants of the Chapeltown and Leylands quarters have since moved to more spacious districts like Moortown, in the northern part of the city. The area has several synagogues, the most frequented one being the Beit Hamedrash, as well as restaurants, butcher shops, and a few specialized bookstores.

The origins of Marks & Spencer

The Jewish presence in Leeds appears to date from the late 18th century. However, the first synagogue was not built until the mid-19th century and opened in 1860, with Jews using a room for worship before that. About 100 Jewish families lived in Leeds at that time.

Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe settled in Leeds and became largely integrated into the working-class garment industry. Among those who helped develop the industry were Montague Burton and Michael Marks. It was in Leeds in 1884 that the latter, together with Thomas Spencer, founded the famous Marks & Spencer chain.

The third Jewish community of England

In its heyday, the Jewish community numbered 25,000 in the 1920s. By the early 1970s, the city had 18,000 Jews out of a population of just over 500,000. This made it the third largest Jewish community in England, after London and Manchester.

The Leeds Jewish Representative Council, created in 1938, brings together the majority of the city’s synagogues. Among the city’s leading figures were Hyman Morris and J.S. Walsh, former mayors of Leeds, and the academic Shimon Rawidowicz.

In the late 1970s the Jewish population began to decline, reaching 9,000 in the mid-1990s and just over 8,000 in 2001. Reflecting this decline, cashier shops closed in the early 21st century in the Moortown area. Synagogues are trying to regroup in order to continue to function.

Decline of Jewish presence in the region

Nevertheless, the community is making efforts to motivate young people to get involved and keep the institutions running. These efforts, combined with the high cost of living in London, are motivating young people to return. Social and cultural initiatives have been amplified during the Covid crisis.

In 2025, there are between 6,000 and 10,000 Jews living in Leeds. Smaller towns around Leeds where there was also a strong Jewish presence are even more affected proportionally by this decline. The Beth Hamidrash Hagadol synagogue, opened in 1937, is now the largest in Leeds. The United Hebrew Congegration has brought together several older synagogues since 1930. There are also other Jewish streams present through the Reform Sinai Synagogue and the Conservative Leeds Masorti , and the Lubavitch Centre .

There are several Jewish cemeteries in Leeds. These include BHH Cemetery , New Farnley Cemetery , Sinai Section of the Harehills Cemetery and UHC Cemetery .

The Merseyside city of Liverpool, known for being the hometown of the Beatles and one of the most famous football teams, can proudly claim to have been home to northern England’s largest Jewish community in the nineteenth century.

Today, the community centers around Wavertree, the location of the city’s Jewish cultural center at Childwall Road.

The beautiful Princes Road Synagogue

Liverpool boasts one of Britain’s finest synagogues . Consecrated on 3 September 1874, the building on Princes Road is particularly admirable for its late Victorian interior. Be sure to call ahead before attempting to visit.

Jews have probably first settled in Liverpool early in the 17th century. Only 20 were registered there in 1790. In 1860, that number rose to 3000. At the end of the 19th century, some of the Polish and Russian refugees, on their way to the United States, settled in Liverpool.

A Sephardi community from the Levant also settled there in that era. A Liberal synagogue was built in Liverpool in 1928. The Greenbank Drive synagogue presents architectural interests. But the most famous synagogue is the one located at Princes Road, famous on a national scale. In the beginning of the 20th century, a yeshiva, a school and social services were made available.

Since its closure in 2008, plans to convert the Greenbank synagogue into a block of flats retaining the original structure seem to be taking a long time to come to fruition.

The synagogue was built in 1936 by architect Ernest Alfred Shennan, and can accommodate up to 700 people. At its peak in the 1950s, nearly 600 worshippers were members. The decline of Liverpool’s Jewish community, with only around 100 worshippers in the synagogue at the turn of the 21st century, forced the sale of the synagogue.

The only active synagogues in Liverpool are Childwall and Princess Road, the latter being used mainly for large events such as bar and bat mitzvahs and weddings.

In January 2025, Liverpool’s under-18 team visited the Manchester Jewish Museum as part of the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. The aim was to give young people a better understanding of Judaism and the history of the Shoah, and to combat prejudice.

In September 2024, the Princess Road Synagogue celebrated its 150th anniversary. Numerous events were organised, including concerts, lectures, guided tours and ceremonies.

In 2025, there will be around 2,000 Jews in Liverpool.

Participation of Jews in the development of the city

Grateful for the warm welcome and the access to all levels of society, much more than in most other English cities, Jewish refugees vividly encouraged their children to integrate, first and foremost through school, and participate in the radiance of the city. Which explains the great number of local public figures, politicians (among them a few mayors) and lawyers.

Among the biggest contributors to the city’s heritage are two major families: Lewis and Cohen. The Lewis family is best remembered today for the department store founded by entrepreneur David Lewis, operating from 1856 until 2010, carrying their name (on which stands the famous statue by Jacob Epstein celebrating the resurgence of Liverpool after World War II).

Brian Epstein, The Beatles’ manager

Also important to the city’s development is the Cohen family, whose name was given to the library of the University of Liverpool. Those two families have financed many local institutions.

Among the Jewish personalities of Liverpool, we can mention zionist leader Samuel Jacob Rabinowitz, as well as the future Chief rabbi of Israel, Isser Yehudah Unterman.

And of course Brian Epstein, the famous manager of the Beatles who discovered them in a small club and represented their driving force through their fabulous rise. Cynthia Lennon regrets the fact that Brian’s part in their success was much underestimated.

An exhibition of documents from the Merseyside Jewish Archives was held in 2025 in the Picton Reading Room of Liverpool Central Library, located on William Brown Street. The items on display date from 1805 to 2020 and include an illuminated list of members of the Walnut Street Synagogue dating from 1913.

Interview of Howard M Winik, former chairman of the Merseyside Jewish Representative Council.

Jguideeurope: What is the role of the MJRC and its future challenges?

Howard M Winik: MJRC (Merseyside Jewish Representative Council) is the umbrella organisation of the community and provides leadership for all Jews of Liverpool, Wirral, Southport and Chester, whether Orthodox, Reform, Masorti or unaffiliated. We currently have around 3000 members, of all ages and a well-established infrastructure, including synagogues, schools, a dedicated Jewish welfare hub and a care home. In addition, there are several local universities, and we provide activities for every age group. Our numbers reflect employment patterns over the past 20 or 30 years, when many younger people moved to London and elsewhere to find work, although the area has undergone significant regeneration recently and, at present, our local population is fairly stable numerically. There has been considerable investment in the science and biotechnology sectors, which are attracting people into the area, so we are very upbeat about the future. That said, we are entirely self-sufficient financially, and our main challenge is maintaining the resources to fund the services we provide.

How is the Jewish heritage shared in Liverpool?

We encourage people to visit our museums; there is an excellent section at the Museum of Liverpool (close to the cruise terminal) describing the history of the once large Jewish community that lived in the centre of the city. Visitors can also book a tour of one of our local synagogues, and Liverpool Old Hebrew Congregation, in Princes Road, boasts a magnificent, Grade 1 Listed building, decorated in the baroque style, which is one of the finest anywhere. It is also near the Pier Head and City Centre. A number of local Jewish cemeteries are open to visitors too, and the Deane Road grounds have been fully restored and are of particular historical interest (contact Princes Road Synagogue for details). Liverpool also has a Chabad Centre and an active student chaplaincy. We have deposited large archives of historical material with the City of Liverpool. Specific inquiries should be directed to the local records officer, museums, or our community office at Shifrin House.

Is the Beatles Museum devoting an important part to Brian Epstein’s influence?

There is a considerable amount of information available about the Beatles, the Epstein family, and the history of pop music in the museums and elsewhere. Brian Epstein is buried in the Greenbank Synagogue, Long Lane Jewish cemetery in north Liverpool (visits by appointment only) and we encourage people to take a Beatles heritage bus tour too.

With 30,000 Jews, Manchester, known mostly for its 2 famous football teams, has the highest Jewish population in Great Britain after London.

The Jewish presence in Manchester seems to date from the late 18th century, with many of them coming from Liverpool. Its first synagogue was built at this time, under the leadership of the brothers Lemon and Jacob Nathan. It moved to Garden Street in 1794, then to Ainsworth Court in 1806, to Halliwell Street in 1825, and finally to Cheetham Hill in 1856, completing this long nomadic cycle until the late 1970s. Land for a Jewish cemetery was acquired in 1794.

Development of Judaism in Manchester

In 1856, a liberal synagogue was established. At this time, Jews from Eastern Europe also arrived, fleeing persecution. In 1871, Jews from North Africa and the Middle East settled in Manchester. And at the end of the 19th century, following political events in Eastern Europe, more Jewish refugees crossed the Channel. As a result of these arrivals, two new synagogues were built in 1871. The first on Oxford Road for Jews living in the south of the city. The second was on York Street for Sephardic Jews.

Gradually, Mancunian Jews moved out of the city centre to the suburbs and small towns around. In Salford, Prestwich and Whitefield in the north. In Cheshire in the south. They worked largely in the crafts and cloth industries. Educational and cultural development also took place, for example with the establishment of the Jewish Telegraph newspaper.

In 1910, the city had nearly 70 synagogues for 35,000 Jews in its golden age. Manchester’s Jewish personalities included Labour leader Harold Laski, author Louis Golding, businessman Harry Sacher and one of the historic leaders of Marks & Spencer, Israel Seiff, as well as Chaim Weizmann, the future first Israeli president who lived there from 1904 to 1916. Israel Seiff brought together other businessmen to raise the funds to establish the Weizmann Institute in Israel.

During the Second World War, Manchester took in Jewish refugees. The community was very active in helping the British war effort.

Decline and rebirth of Jewish life

Manchester’s Jewish population began to decline from the 1970s. Twenty years later there were 27,000 Jews in Manchester and by 2001 there were less than 22,000. At that time there were 32 synagogues, the vast majority of which were Orthodox. Most Mancunian Jews lived in the suburbs of Bury and Salford.

By 2011, the Jewish population had grown to 25,000 Mancunians, and by 2021 to almost 30,000. Nevertheless, Mancunian Jews have been the victims of numerous antisemitic attacks over the past decade. Regular attacks on people and on the Jewish cemetery, when in 2018 dozens of headstones were destroyed. A study in the same year determined an increase of these attacks by 25%.

Synagogues active today include Bowdon Shul , opened in 1873 and the oldest congregation in South Manchester, Mead Hill Shul dating from 1904, the Orthodox Heaton Park Hebrew Congregation founded in 1935, and the Menorah Synagogue , which is a member of the Reform movement and also serves as a Jewish cultural centre for South Manchester residents.

Among the Jewish cemeteries of Manchester, we can mention Whitefield , Urmston , Southern , Pendleton , Rainsough et Prestwich Village .

Renovations and expansion of the Jewish Museum

The Jewish Museum of Manchester was established in 1984 to share the history of their presence in the city and their contribution to its development. It is housed in the former Spanish and Portuguese synagogue on Cheetham Hill built in 1874. Behind its red brick façade, the museum’s architecture blends Victorian and Moorish styles.

The Museum has been renovated and modernised. Its reopening in and extension opened in May 2021 allowed the public to discover the work undertaken. Amongst the objects on display are those belonging to the Jewish refugee Helen Taichner, recounting her journey and her joy and relief at being able to obtain a visa for England and settle in Manchester. In the same spirit, the various arrivals of Jews from three continents and their active participation in the development of Manchester are presented.

The city has suffered numerous anti-Semitic attacks, which have skyrocketed since the pogrom in Israel on 7 October 2023. Unfortunately not lacking in imagination, anti-Semitism attacks all sorts of targets. This was the case at the end of 2024 when the two busts of Chaïm Weizmann were stolen from the University of Manchester. The man who was to become the first President of the State of Israel taught at this very university at the beginning of the 20th century.

In January 2025, Liverpool’s under-18 team visited the Manchester Jewish Museum as part of the 80th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. The aim was to give young people a better understanding of Judaism and the history of the Shoah, and to combat prejudice.

On 2 October 2025, a terrorist drove his car into a crowd gathered outside the Heaton Park Synagogue, where Yom Kippur was being celebrated. He then got out of his car and stabbed several people, killing two, Adrian Daulby and Melvin Cravitz, and injuring three others. Many Britons showed their support for Manchester’s Jewish community, including King Charles III, who visited the scene of the attack.

Oxford’s oldest synagogue was transformed into a tavern, then incorporated into one of the university’s oldest colleges, Christchurch. There is, however, a new synagogue. It was built in 1974, on the site of an older one from 1880, of which only a wall remains.

For three centuries, the cellars of tumbledown houses in the old town were home to a hidden Jewish community, that of the conversos who came here from Spain after 1474. Used to hiding their faith in Spain, these “new Christians” continued to practice their old religion in secret when they came to France. Bordeaux’s Jewish community began to emerge from the shadows only in the mid-18th century.

Ancient texts record the presence of Jews in Bordeaux from as early as the 6th century. A document dating from 1072 evokes a “Mont-Judaïque” which would have been on the outskirts of the ancient city of Bordeaux, where the streets Mériadec and Dauphine are currently located. It is in this sector of the city that the Jewish cemetery was located.

When the city of Bordeaux was under English rule (from 1154 to 1453), the Jews had to face threats of expulsion and high taxations by the British as well as by the regents. The Jews of Bordeaux were then organized under the banner “Community of the Jews of Gascogne”.

The Inquisition caused the departure of many Jews from Spain and Portugal. Some of these arrived in Bordeaux. Many Marranos thus settled in the city in the middle of the 16th century. Nevertheless, this acceptability underpinned the Christian life of these Portuguese Jews who could not resume their ancient rites. A municipal declaration stressed in 1734 that the practice of the Jewish religion was prohibited. A report drawn up in 1753 took offense at the fact that this religion was practiced in seven places designated as synagogues when it was in fact private places of prayer in apartments.

In 1725, Portuguese Jews bought land that allowed them to have a cemetery . It was used until the French Revolution and was definitively closed in 1911. The Avignon Jews bought a cemetery in 1728, which was in service until 1805. A third cemetery was opened in 1764 by the Portuguese Jews, which was gradually used by the whole community of Jewish women from Bordeaux.

The number of Jews in Bordeaux was still relatively low at the start of the 18th century. Indeed, the Sephardic community of Bordeaux and the Avignon Jews totaled less than 1800 people. This did not prevent threats of eviction during this century.

On the eve of the French Revolution, the Jews of Bordeaux sent two representatives to meetings organized by Chrétien-Guillaume de Lamoignon Malesherbes, advisor to Louis XVI, to discuss the Jewish condition in France. When this assembly ultimately decided to postpone a decision on the status of Jews and their right to equality as citizens, seven representatives of the community of Bordeaux argued their case before the Paris authorities. Meanwhile, the Declaration of Human Rights adopted on August 26, 1789, put an end to all discrimination against citizens. However, the Constituents do not agree on the status of the Jews. This resulted in a partial decree dated January 28, 1790, which stipulated that Portuguese Jews became the first active citizens. The emancipation of all Jews in France would be achieved a year later, on September 27, 1791.

When a census was presented in 1806, there were 2,131 Jews in Bordeaux. Among them, 1,651 from Spain or Portugal, 336 from Dutch, German or Polish origin, and 144 from Avignon. Abraham Furtado, who had participated in the Malesherbes Commission, is also present at the Assembly of 106 notables gathered by Napoleon, where he represents the Gironde. He will also be a member of the municipality of Bordeaux and will become deputy mayor. Following the sessions of the Grand Sanhedrin that took place a year later, the Consistory of Bordeaux was in charge of ten departments.

Abraham Andrade was appointed Chief Rabbi. The Great Synagogue on rue Causserouge was opened in 1809, allowing Jews from Bordeaux to leave the reclusive prayer halls. It was designed by architect Armand Corcelles in an oriental style.

During these years, a Jewish school and a talmud torah were opened. Equal rights and duties also motivated participation in the public service and in political life. Thus, Jews from Bordeaux participated in municipal councils, and personalities like Salomon Camille Lopès-Dubec, Joseph Rodrigues and Adrien Léon were elected to the National Assembly.

The Great Synagogue of Bordeaux was destroyed by fire in 1873. This motivated the community to entrust the project of a new synagogue to the architects Paul Abadie and Charles Durand.

The synagogue was inaugurated in 1882. The architectural inspiration was of a mixture of Gothic and Oriental styles. The interior decoration is of Syrian, Ottoman, Egyptian and Moorish inspiration. The whole resulting in a majestic building and very original from an architectural point of view.

During the Second World War, the occupation in Bordeaux was very brutal. 1600 Jews were deported thanks to the zeal of the Collaboration. Among them was Maurice Papon, the sub-prefect in charge of German requisitions, the occupation service, and the Jewish affairs office. In 1998, he was sentenced to ten years’ imprisonment. A monument has since been erected in their memory.

The great synagogue, built in 1882, was pillaged during the Shoah and transformed into a gathering place before the deportations. After the war, the synagogue was restored, becoming the largest Sephardic rite synagogue in France.

Since then, the Jewish community of Bordeaux has grown with the arrival of a new Ashkenazi congregation and the arrival of Jews from North Africa in the 1960s.

Among the places of Jewish cultural life, we find the Yavné Center , opened in 2000, following the closure of the Bordeaux Community Center on Place Charles Gruet. The city benefits from a Beth Halimoud created ten years ago by Sébastien Allali.

Another important place in the city to visit, the Jean Moulin National Center in Bordeaux , named in tribute to the great Resistance fighter. Created at the instigation of Jacques Chaban-Delmas in 1967, this museum and documentation center on the Second World War presents collections devoted to the Resistance, the Deportation and the Free French Forces. The Center has been closed to the public since 2018.

The Jewish cemetery established in 1764 is today the only one in activity. The 18th century tombs are simple rectangular slabs. In the following century, cippi, sarcophagi, cenotaphs and stelae in the form of law tables were used.

On 10 January 2024, the Jewish community marked the 80th anniversary of the round-up of Jews in Bordeaux. The tribute took place in the Bordeaux synagogue, where the names of the 365 people arrested on 10 and 11 January 1944 and then taken to Drancy were read out. Among the fifty or so children who were locked up in the synagogue was Boris Cyrulnik, six years old at the time. The author, who survived the roundup by hiding in the building, took part in the ceremony. The ceremony underlined the importance of passing on the memory and the fight against the increased resurgence of anti-Semitism over the last two decades, and particularly since 7 October 2023.

Following the anti-Semitic act of cutting down the tree planted in memory of Ilan Halimi in Epinay-sur-Seine in August 2025, numerous trees were planted in his memory and to mark their involvement in the fight against anti-Semitism, which has been ravaging Europe since 7 October and the exploitation of conflicts in the Middle East.

The Jewish community in Bordeaux planted an olive tree on 20 October 2025 in front of the Great Synagogue, following a ceremony organised by the CRIF Bordeaux-Aquitaine and the Consistoire Israélite de Bordeaux.

In September 2025, three paintings stolen from the Jewish painter Fédor Löwenstein by the Nazis in Bordeaux in 1940 were returned to his heir. He loaned them to the Museum of Jewish Art and History (mahJ) in Paris for an exhibition. His other looted works remain untraceable for the time being.

Sources: France Bleu, Le Figaro

On the day of tishah b’ab commemoration of the destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem, the old synagogue resounds to these words in Spanish: “Hemos perdido Sion pero tambien hemos perdido. España tierra de consolacion” (We have lost Zion, but we have also lost Spain, land of consolation”).

Bayonne’s synagogue was built in 1837, but its Holy Ark, kept from the earlier place of worship, dates back to the reign of Louis XVI. It is said that even some of the Torah scrolls are of Spanish origin, from before the expulsion of 1492. They are said to have been brought by Marranos fleeing persecution.

Located at the corner of the avenue des Foix and avenue du 14 Avril, the cemetery was created in 1660. It contains the tombs of the community leaders and, surprisingly, those of eighteenth-century Jewish corsairs.

Chocolate at Saint-Esprit-les-Israélites

In the seventeenth century, the Jewish immigrants from Spain were cast out of central Bayonne and settled in Saint-Esprit. This quarter became known in popular parlance as Saint-Esprit-les-Israélites because Jews constituted the majority of its population, which was extremely rare in France. It was a Jew of Spanish origin, Gaspar Dacosta, who introduced the art of chocolate-making to Saint-Esprit, and indeed in France.

The Suzanne et Marcel Suarès Museum of Bayonne Judaism , opened on 2 November 2022, pays particular tribute to the Marranos, Spanish and Portuguese Jews, and traces the history of regional Judaism. It is located on rue Maubec, close to the town’s synagogue. The museum retraces their history and presents the community. In particular, the museum aims to show the contribution of Bayonne’s Jews to the city.

Following the anti-Semitic act of cutting down the tree planted in memory of Ilan Halimi in Epinay-sur-Seine in August 2025, many town halls decided to plant trees in his memory and to mark their involvement in the fight against anti-Semitism, which has been ravaging Europe since 7 October and the exploitation of conflicts in the Middle East.

Among these town halls is that of Bayonne, where an olive tree was planted on 21 September 2025 in the Gardens of the Synagogue, following a ceremony attended by elected officials and local authorities.

Sources: Sud-Ouest

The Museum of Art and History (Musée d’Art et d’Histoire) in Narbonne has the oldest known inscription relating to the Jewish presence in France. It is an epitaph for the three children of Paragorus: Justus, aged thirty; Matrona, twenty; and Dulciorella, nine. Absolute proof of the Jewishness of the inscription is given by a seven-branch candelabrum and a short text in Hebrew: “Peace on Israel”. The museum also has a funerary inscription.

The Jewish presence in Narbonne seems to date at least from the 5th century, as confirmed by letters written in 470 and 473. In the 7th century, stones found with inscriptions in Hebrew and Latin attest to this presence.

As stated in the Special Edition of the Midi Libre newspaper devoted to the Jews of Occitania, according to a legend, Charlemagne would have granted many privileges to the Jews following his conquest of Narbonne. Among them was the possibility of having a “king”, an important representative of the community.

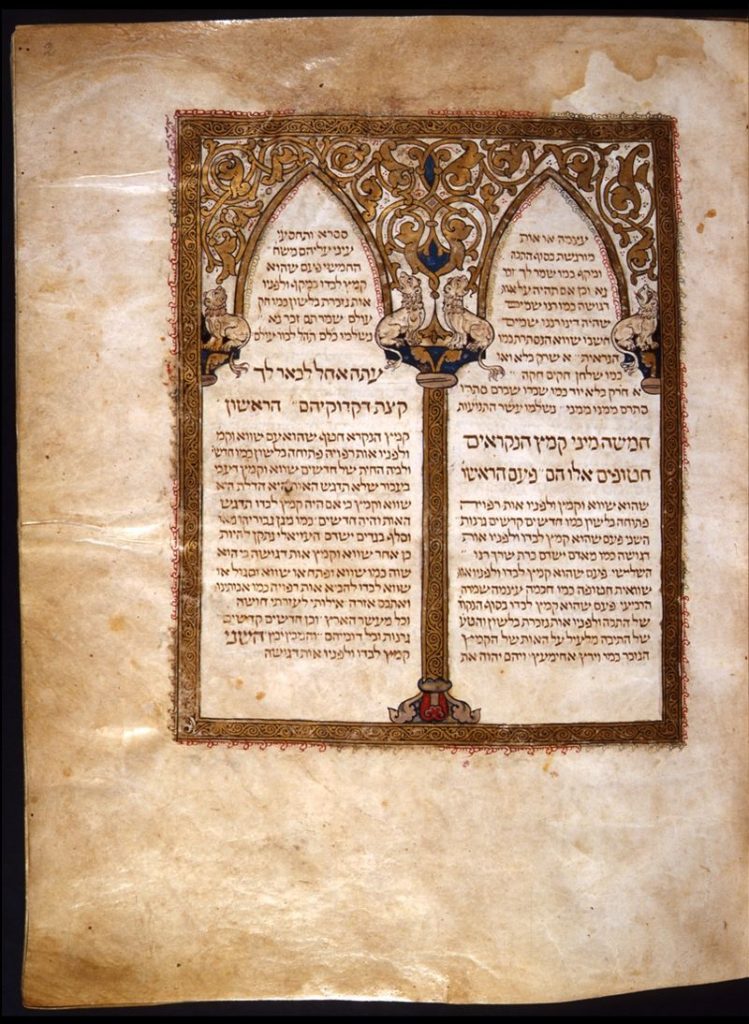

In his Travel Diaries, Benjamin de Tudela indicates that Narbonne is known for its scientific and now biblical prowess, thanks in particular to the contributions of the Jews. Among the great scholars, he mentions Rabbi Kalonymos. He also had the privilege of being able to seal public documents with a seal on which appeared the lion of Judah. And also Jaccaben Jekar, one of Rashi’s masters.

From the 12th century, the Jewish population of this flourishing medieval city increased, mainly due to the arrival of Andalusian Jews. Among them are great scientific, literary and Talmudist researchers. Who share this knowledge in different languages, whether it is Spanish, Arabic, the original languages and Hebrew and French, the language of the host country. David Kimchi, one of these great scholars and the son of an exile, is the author of Sefer Hashorashim.

The Jewish community of Narbonne contributes to the development of the city and enjoys the great freedom granted by local authorities, whether political or religious. It seems that the discriminatory measures of the Lateran Council are little followed.

On the other hand, the murder of a fisherman in 1236 sparked local riots among the population, leading to violence and looting. Just before the great expulsion of 1306, the city had 825 Jews, constituting almost 4% of the total population.

Around 20 Jewish families currently live in Narbonne, partly from the arrival of Jews from North Africa in the 1960s. A synagogue welcomes the faithful.

In September 2024, Narbonne’s Jewish Culture and Heritage Association took part in the European Heritage Days. With the help of guides, the public discovered the long Jewish history of Narbonne.

The Jewish presence has been attested in Béziers since Roman times, but the golden age of the Jews of Béziers is undoubtedly the classical Middle Ages, when the city was nicknamed the “Little Jerusalem”, both because of the importance of its community and because of the sight that one had from the plain of Orb, resembling Jerusalem.

Its rabbinical school was renowned, and Benjamin of Tudela, in his travel notebook, will evoke a city “where wise men abound”. Many rabbis and scholars adopted the nickname” Beders “(Béziers in Hebrew), in honor of their city, including the poet Abraham Bedersi and his son Jedaiah.

The situation of the Jews of Béziers was much more enviable than that of their Languedoc co-religionists, thanks to the protection of the vassals of the region, the Trencavel, who used the support of the Jewish community to govern the city. This golden age came to an abrupt end in 1209 during the Albigensian Crusade unleashed by Pope Innocent III.

Béziers then Carcassonne fell into the hands of the Crusaders. 200 Jews perished at the sacking of Béziers; the remaining 200 had already left the city under the protection of the viscount.

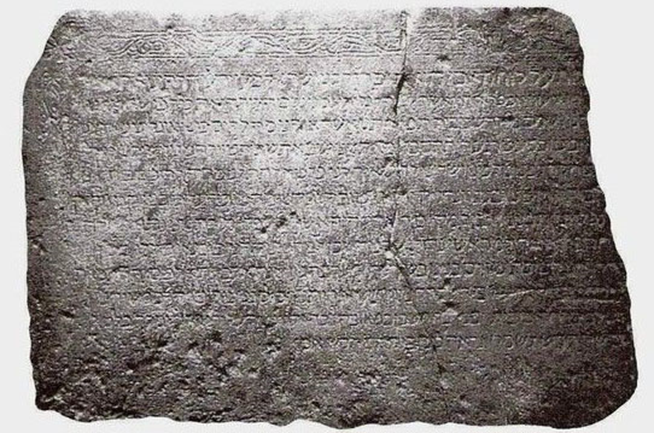

At the fall of Carcassonne, the Jews of Béziers took refuge in Catalonia and rebuilt a community in the small town of Olot. They engrave the dedication of their new synagogue in a stone, inscribing the pain of exile, and the loss of their city. The toponym is Béziers in Hebrew, “Beders”, and the war to which it is referred is dated 4969, which corresponds to the year 1209 of the common era. It is therefore an evocation of the crusade of the Albigensians.

This stone was found in the 1940s, in the ruins of the chapel of the cemetery of Olot, burned at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War. It is currently exhibited at the museum-treasure of Sant Estève of Olot church.

A few years later, the Jewish refugees at Olot, or part of them, return to Béziers. They erect a new synagogue. The dedication is dated from the year 4900… The vintage is missing because of a break of the stone, but research has led to deduce that it would be the year 1214.

On the western facade of the cathedral Saint Nazaire two allegorical statues representing, one the “synagoga” deprived of its attributes and blindfolded, the other the “ecclesia” triumphant. Inside the cathedral, you will find in two places the Hebrew letters of the divine tetragrammaton.

Finally, if you walk in Béziers, some streets reminds of the Jewish past of the city. At 28 street du 4 septembre is the site of the former royal synagogue, where the Hebrew stone of Béziers was found. The Petite Jerusalem street leads to the former episcopal Jewry, located on rue Boudard. unfortunately destroyed in 1944. The streets of Capus and Soleil, are the vestiges of a former Jewish quarter surrounded by the 2 branches of the “U” drawn by the street of Capus, and whose Roman porch which controls the entrance of the street of the sun would have been the access door. Regular events are organized in Béziers. For more information about the upcoming events you can check www.memoirejuive-beziers.org

The Synagogue of Béziers has been welcoming a Jewish museum since the summer of 2020, prensenting Béziers’ Jewish history and a copy of the famous Hebrew stone.

The restoration of the synagogue in Béziers was completed in 2024. It was carried out by craftsmen from the Biterrois region, working on the gilding, tapestries and lighting. The event was celebrated by Maurice Abitbol, president of the Association cultuelle israélite de Béziers (Acib), at the reinauguration of the synagogue. In the flat where the rabbi used to live (he now lives elsewhere), the Jewish museum has been extended to cover an area of 150 m2. In the dining room, a table has been set up with the same decorations used throughout the year, evoking the different Jewish festivals. Two other areas retrace the history of Eastern European Jews and Sephardic Jews.

Source and photo credit : Association Mémoire juive de Béziers

It was around 1298 that the Jews settled in Pézenas, coming from Spain, Portugal and Italy. In the trade of clothes and cattle, they added the activity of the sale of wool and sheets. In 1332, a law imposed on the Jews crossing Pézenas or coming to sell there, a right of “leude” (a grant, or a toll). Jewish families disappeared from the city in 1394, during the expulsion of the community of the kingdom of France.

In Pezenas, the medieval Jewish district is circumscribed to the street of Juiverie and street of Litanies. An earthen tank forming a small basin in the basement of a house that could be a mikveh was also found.

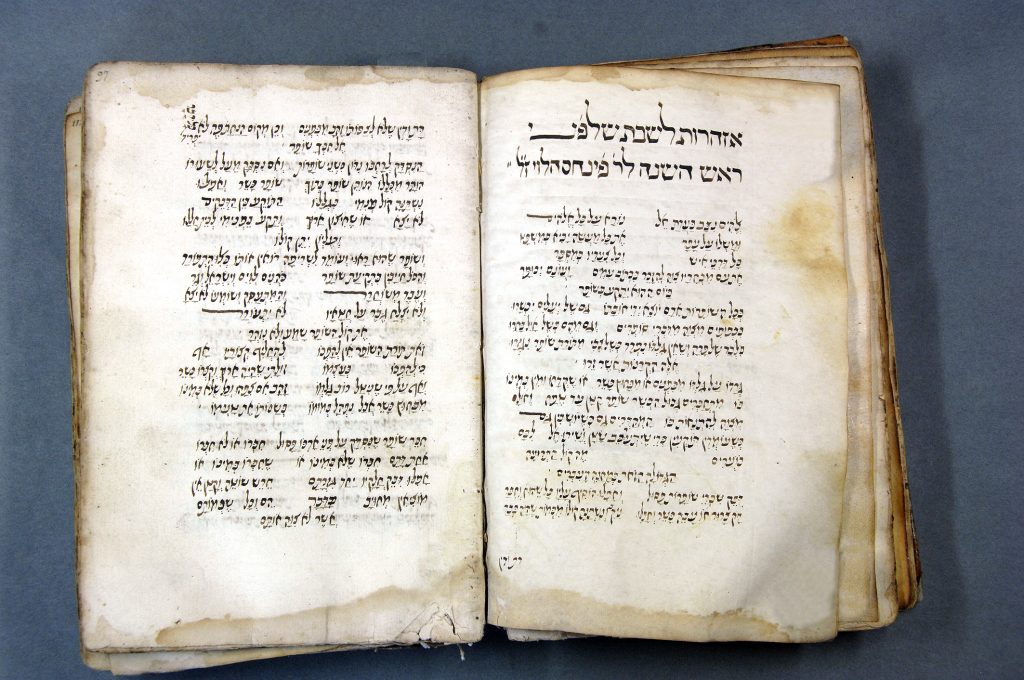

The traveler Benjamin of Tudela visited Montpellier in 1165. In his travel diaries, he noted the existence of Batey midrashot kevouot le-Talmud in the city. In addition to these intellectual activities cited in a Hebrew source, Latin documents relate the presence of Jews in trade between Agde, Narbonne and Montpellier. They had a monopoly on silks and fabrics. Representatives of the Mosaic Law were also involved in the effort to protect the city.

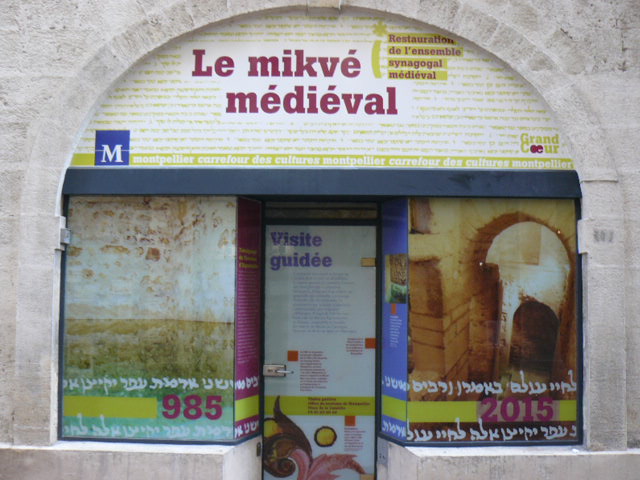

The current rue de la Barralerie is the old central street of the Jewish quarter in the seigneurial stronghold of Guilhem. The religious complex includes a place called synagogal, a house of alms (domus helemosine), a house of studies, and the medieval mikveh , which has been found and restored, all components of the Schola Judeorum; it can be visited at n ° 1 on the street. We can see the 12th century bath having escaped the roughness of time, the undressing room, as well as the basin with its seven underwater steps and its wall orifice decorated with a gargoyle (the first two deepest are from medieval times). A jewel of Romanesque art, made by Christian architects at the request of the Jewish community, it is one of the two oldest religious monuments in the city.

Visible with the Montpellier Tourist Office, this hotspot of Montpellier’s memory is part of an exceptional medieval synagogal ensemble which has been the subject of in-depth archaeological excavations carried out by Christian Markiewicz, associate member of LA3M (Laboratory of Medieval and Modern Archeology in the Mediterranean) and the City of Montpellier. Philippe Saurel, Mayor and President of Montpellier Méditerranée Metropole was very involved in these archaeological investigations, which led to the recent update of additional basins, pavements and spaces adjoining the 12th century Jewish ritual bath.

A Jewish quarter open to mixed Judeo-Christian habitat developed in the 13th century, around rue de la Barralerie, with the mikveh, which was, let us remember, re-discovered in the early 1980s, restored, and then inaugurated in 1985, during the millennium of the city by Georges Frêche, on the occasion of the organization by Carol Iancu, professor at the University Paul Valéry Montpellier 3, of an international scientific symposium on “The Jews in Montpellier and in the Languedoc ”.

The 14th century was the century of the expulsion of the Jews from France, marked by dismissals (1306 in particular, then 1322 and 1394) and successive reminders (1315; 1359) of the French monarchs. The Jews settle during the last authorized period (1359-1394), rue de la Vieille Intendance very close to the old habitat. Montpellier will have been the scene of famous Maimonidian controversies: a 1st time in 1230, around the writings of RAMBAM: a copy of the Guide of the Perplexed, would have been according to Hillel of Verona, destroyed in public place; a second time around the 1300s against philosophy. Athens and Jerusalem: should we understand the Mosaic law in the light of the Greek sophia? A fideist reading or a reading supported by reason? Intellectual excitement in any case. It is not fortuitous that this takes place in Montpellier, a place of intellectual and theological profusion, and within the Jewish world.

In the 17th century, Jews from Comtat Venaissin had temporary permits to trade in Montpellier.

From 1714, nine Jews settled in the city. Others follow this approach. At the beginning of the 19th century, the Jewish community numbered a hundred people. It was then directed by Moïse Milhau, who represented the Vaucluse department with the Grand Sanhedrin.

Around 60 families made up the Montpellier Jewish community on the eve of the Second World War, or 300 individuals, participating in the celebration of shabbat and festive times; foreign Jewish students (many in medicine) could join them. In 1940-41, and even in 1933 with the rise of Nazism, the installation of anti-Semitism and the introduction of the numerus clausus in the countries of the East (Germany, Hungary, Poland, Romania) is increased by Jewish refugees: 150 homes gathering 750 people, manifested by their contributions, and tangible memberships. A proportion is revealing in this respect, with in 1933, out of 800 French and foreign students registered in medicine, the tenth of Romanian Jewish students amounting to 80!

The place of worship, first located on rue du Jeu de l’Arc, took place on rue des Augustins (now a Protestant temple). Cesar Uziel, of Ottoman origin, who arrived in Montpellier in 1933, first held the office of minister, then that of president of the community, succeeding Leon Brunschwig (died 1934). After him, Louis Kahn will officiate for five years.

In the summer of 1940, refugees from Belgium, Holland, Luxembourg, especially Poland, but also from Alsace-Lorraine and Paris arrived massively in Montpellier. Despite some reluctance, a surge of solidarity is taking place.

With the precious support (obtaining false identity cards) of the Prefect Benedetti, and the Secretary general of the Prefecture of the Hérault Camille Ernst (to which the City recently paid homage), César Uziel (1892-1983) took care of a first group of 250 foreigners, distributed in Montpellier, to the neighboring villages and the hinterland. The main part of this first wave was directed towards Lozère (Lancogne) for a temporary halt.

This does not exclude the whole apparatus of deportations, spoliations (which I have treated widely elsewhere, works in 2000 and 2007), with its harmful lot of denunciations, cowardice, an anti-Semitism erected in State doctrine, the roundups of the fateful summer 42, and internments in the camps of Rivesaltes, and – for the geographical area of Hérault – in that of Agde.

Heroic facts of hope: located in the free zone, Montpellier has served as a refuge for at least fifteen different nationalities, the majority of them Polish (half). The Faculty of Letters welcomed – despite the faux pas of the farrier Augustin Fliche (contrary to the generous attitude of Pierre Jourda) – the great medievalist Marc Bloch before he was shot in Lyon for acts of resistance (1944) ; the Faculty of Medicine was exemplary, thanks to the remarkable action of Dean Giraud (1888-1975) and Professor Balmès (1904-1986) towards hidden Jewish students, defended despite the iniquitous racial laws of the Vichy government, and authorized (“under the cloak”) to take the courses and take the exams.

Throughout these grim years, there are acts of bravery and self-denial of bright men and women who, at the cost of their freedom, risking their lives, saved Jews from the pangs of barbarism. These are the Hassidey Oumot ha-Olam or “Righteous Among the Nations” celebrated by the Yad Vashem Institute in Jerusalem which keeps alive the memory of the six million victims of the Shoah, thereby awarding the “Medal of the Righteous.” Many valiant Montpellier residents have received this high distinction.

At the end of the war, the bloodless Jewish community (about fifty families of Alsatian, Ashkenazi and Turkish origin for the most part) is a mosaic bruised by the Shoah.

In 1946, from rue Marceau to rue des Trésoriers de France, the place of worship of the Association Cultuelle Israélite de Montpellier (ACIM) changed. The Board of Directors, under the direction of César Uziel (who had helped stateless co-religionists fleeing the German advance during the war), acquired the ground floor of a building on rue des Augustins. The synagogue inaugurated in 1952 remained there until 1985, before its transfer to rue Lafon, alongside the synagogue known as Mazal Tov , rue Proudhon. The year 1956 saw the arrival of Rabbi Roger Kahn, whose youthful dynamism changed the community, also following the opening in 1957 of the new Community center on Avenue de Lodève.

The arrival of Jews from North Africa is a historic turning point in Montpellier, as everywhere else in France. Members of the community, all origins combined, accompany these refugees, who have to adapt to countries, Mediterranean certainly, but different in many respects; the newcomers bring a legacy of the warmth of the East, infused with ritual rigor. Their uninhibited and exuberant Judaism revitalizes the community group which remained tenuous.

The arrival of Georges Frêche’s responsibilities was decisive for the Jews. Through his tangible achievements, he becomes a “Jew at heart” for the 6,000 Jews from Montpellier. He left his mark on the Jewish community that was acquired to him.

Let us naturally remember the restoration of the medieval mikveh during the millennium of the city; or even the twinning with Tiberias (where, according to tradition, Maimonides is buried) – already weaving a link between Maimonides and the medieval “City of the Mount” (Ir ha-har, in Hebrew).

In the 1980s and 90s, the development of Montpellier Judaism crystallized around the creation of Radio Juive languedocienne (RJL), today Radio Aviva, co-founded by Carol Iancu to whom we also owe co-discovery of the medieval mikveh of the city, and who also created at Paul Valéry University, the Center for Jewish and Hebrew Research and Studies (1983).

Another offshoot of the Jewish Community and Cultural Center of Montpellier (CCCJ) in 1978 is “The Day of Jerusalem”, an annual popular gathering. The “Jewish and Israeli Film Festival”, which disappeared early, had the merit of dealing with the diversity of Israeli cinematographic creation in a city with a long Zionist memory: there were four Montpellier Jewish delegates to the 1897 Basel Congress, negotiations took place in the prefecture for the departure of the Exodus in Sète.

The 2000s were marked by the creation of a Jewish school and college, as well as the French Committee for Yad Vashem. A generational renewal is manifesting.

Following the discovery of one of the oldest (12th century) European mikvaot, and starting from the observation that in Montpellier, medieval Judaism experienced a golden age until the expulsion edicts of the 14th century, the academics Georges Frêche and the former Chief Rabbi of France, René-Samuel Sirat, created in 2000 the Euro-Mediterranean University Institute of Maimonides (IUEMM) with a view to re-inscribing the medieval figure of Maimonides in the City. The Institute that has established itself in the local cultural landscape is located above the medieval mikveh in the historic Barralerie building where 700 years ago – Jewish passions around philosophical thought clashed.

Developing the history and civilization of Judaism and Israel, fostering interreligious dialogue, constitute the founding axes of this Institute. The room known as “Don Profiat” perpetuates the memory of the last of the Tibbonids.

The Municipality offers since 2008 with the help of the IUEMM and the “New Gallia Judaica”, CNRS team which was integrated in the historic building of the Barralery for a decade, seven didactic showcases for passers-by, which relate the history of medieval Hebrew Montpellier. That is to say if the glorious medieval Jewish history sounds “strong”, as it is said in music, in the “City of Mount”!

Unmissable place of Montpellier, the Maimonides-Averroès-Thomas Aquinas University Institute , whose skills in the daughter religions of monotheism – Christianity and Islam -, were enlarged by Philippe Saurel, Mayor of the City and President of the Metropolis, many events and visitors.

The history of medieval Montpellier and Languedoc Judaism is a story of Judeo-Christian encounters around the Greco-Arab legacy; and also and above all a story of Hebrew passions around Maimonides’ thought and philosophy; passions exacerbated even in the synagogue of the 13th century Jewish quarter, the very place where the Institute is based: a nod to History, undeniable topographical legitimacy.

The city of Montpellier plans to create a museum around the medieval mikveh as part of a restoration and enhancement project for the site. The museum is expected to open in the early 2030s and will feature an immersive and educational tour, as well as an exhibition space and rooms for research, documentation and conferences.

Page created with the help of Michaël Iancu, Doctor of History and Director of the Maimonides-Averroès-Thomas Aquinas University Institute. Michaël Iancu is the author of Spoliations, déportations, résistance des Juifs à Montpellier et dans l’Hérault, 1940-1944 (Barthélémy, 2000), Vichy et les Juifs. L’exemple de l’Hérault, 1940-1944 (Presses Universitaires de la Méditerranée, 2007) Les Juifs de Montpellier et des terres d’Oc. Figures médiévales, modernes et contemporaines (Cerf, 2014) and texts for the collective works Ombres et lumières du Sud de la France. Les lieux de mémoire du Midi (Les Indes savantes, 2015 et 2016), Nouvelle Histoire de Montpellier (Privat, 2015).

Interview of Michaël Iancu

Jguideeurope : The city of Montpellier is very involved in sharing Jewish cultural heritage. How do you explain this commitment?

Michaël Iancu: Without an apologetic interpretation of local history, it is important to know that in the Middle Ages, Montpellier is not far from having represented an oasis of tolerance, or at least progress in knowledge, in welcoming individuals wherever they came from, opening up to science wherever they came from. Historians have highlighted the privileged place of the city of Montpellier, close to Spain, trading with the Arab world, benefiting from the proximity of Jewish scholars established in Lunel or Béziers.

It is significant moreover that the program of the license in 1309 juxtaposes Galien, Avicenne, Rhazès and Isaac Israeli, in other words the ancient, Arabic, and Jewish medicines of Arabic expression. The Jews were in this “Little Cordoba” that was Montpellier for the medieval period, passers of cultures between Muslim Iberia and feudal Christianity. So, quite naturally, the municipality wanted to find the Jewish roots of the city. Roots certainly essentially Christian, but with significant Hebrew interference.

The discovery of the mikveh is fairly recent. What have we discovered and established about its use in the Middle Ages?

Montpellier is fortunate to have, over the ages, a first-rate archaeological vestige: the mikveh, a Jewish ritual bath dating from the 12th century, known to ancient local scholars (such as Canon Charles d’Aigrefeuille in 1737), found and restored in the millennium year of the city in 1985.

Moreover, the medieval synagogal building where the Institute is based, was declared a “Historic Monument” in 2004, and is currently the subject of investigations carried out by the DRAC and the City of Montpellier with its mayor Philippe Saurel, very involved in the revaluation of the medieval Hebrew Montpellier heritage. Purpose: to try to update the medieval place of worship, the house of alms (domus helemosine) and the house of studies, components of the Schola Judeorum according to cross sources, Latin Christian and Hebrew.

By its name, this place today represents a unique place of openness and meeting. Can you meet us intercultural that marked you?

A Meeting in 2004, Rabelais room in Montpellier, entitled: “The Brotherhood of Abraham, a wishful thinking? Score for a quartet in unison?” with René-Samuel Sirat, founding president of the Maimonides Institute and former Chief Rabbi of France; Dalil Boubakeur, (then) Rector of the Great Mosque of Paris, Jean-Arnold de Clermont, (then) president of the Protestant Federation of France and Guy Thomazeau, (then) Archbishop of Montpellier.

Do you notice any changes in audience expectations compared to the pre-Covid period?

The public has returned in large numbers after the Covid-confinement period even though vigilance is still required. We now film all our events and post them on our YouTube channel. This way, people who cannot travel do not miss out on the Maimonides program.

How do you explain the great success of the Midi Libre’s special issue devoted to Occitan Judaism and is it still available online?

There is a growing interest in better understanding our common history. Montpellier and more broadly the Languedoc region were, for the medieval period, a land of passage and mixing, of Judeo-Christian encounters around the Greek-Arabic legacy. For a long time, all Jewish origins, whether familial or patrimonial, were denied. Today, without going so far as to be proud of it, there is a real curiosity about the Jewish roots of France and Europe, roots that are eminently Christian but also Hebraic. The success of the special issue can be explained in part by this.

A seaside resort, Antibes is best known for its jazz festival. The Jewish community of Antibes-Juan-les-Pins was created in the 1960s, following the arrival of Jews from North Africa. The synagogue was built in 1990 and also houses a cultural centre.

In November 2024, around a hundred people gathered at the Rabiac cemetery in Antibes to bury Denise Holstein, a Holocaust survivor who died at the age of 97.

The Picasso Museum possesses the mold and a cast of an original inscription, now lost, in Greek characters (in ancient times, Antibes was called Antipolis): “Justus son of Sials, he lived seventy-two …”

An important village in the Middle Ages -it has a studium papale– Trets had a Jewish community that lived in the present-day rue Paul Bert, known in those days as the carriera judaica or judea. The Jewish quarter in Trets is not unlike that in Gerona, Catalonia. Sadly, there has been no restoration so far. The medieval facade on rue Paul Bert could be a vestige of the synagogue.

According to the research of Fred Menkès, cited by Danièle Iancu-Agou in her book Provincia Judaica: Dictionary of historical geography of the Jews in Medieval Provence, Trets appeared in 1283 among the list of cities (with Cadenet, Istres, Lambesc, Lançon, Pertuis and Saint-Maximin) authorized to own a synagogue and a Jewish cemetery for an annual royalty in pepper.

Documents dating from 1326 mention a Jewish quarter near the current rue Paul-Bert. Their arrival probably dates from the 13th century and is attested from 1308, renting houses there, remaining the property of nobles and local personalities. The city is then very welcoming towards the Jews, allowing many families undergoing a difficult situation in other cities of the region to find refuge there. Thus, between 1325 and 1339, one finds in Trets four Jews called “de Hyères”.

After two decades they become owners and will subsequently be allowed to acquire property in other parts of the city. The Jewish community became prosperous from the 1330s and real estate purchases were added to those of vines, mainly to prepare the ritual wine and not for trade.

The synagogue is said to date from 1283, the year of the document authorizing its construction in the city. It was located in the old rue des Juifs, now called rue Paul-Bert. The activities of the small Jewish community in the city are managed there, in particular social works to help the poor. The Trets synagogue was sold in 1493, in the wave of forced conversion and expulsion. Despite recent research, uncertainties remain today about the building on this street that would have housed the synagogue.

The census ordered in 1341 by Robert, count of Provence, gave the Jewish population of Aix at the times as 1205, representing the 203 families grouped together in the Jewish quarter.

In her book Provincia Judaica: Dictionary of historical geography of the Jews in medieval Provence, Danièle Iancu-Agou recalls a text quoted by JS Pitton from Archbishop Peter IV that authorizes the Jews to build a synagogue and a cemetery in the town of Tours: “The Jews living in Aix, of whatever condition they may be, rich or poor, noble or not, few or many, from today will henceforth have to pay annually, for Easter, a cens of two pounds of pepper of the best quality to Lord Peter and his successors in the year 1143, and that for the scroll, the cemetery and the lamp.” This synagogue would have been located in a square near the current Celony Street.

In the 14th century, Jews emigrated to the county town, establishing a synagogue there, the presence of which was confirmed by texts dating from 1390 at the corner of the former rue Vivaut and rue Verrerie. An important place of Jewish life during the 15th century, the building and those surrounding it also housed a school, a kosher butcher’s shop, a charity house and social services. The main building will finally be sold in 1501.

Two Jewish cemeteries also existed at the time. The main one probably dates from the 10th century and would have been located between the Puyricard road and the national road. Jews were buried there until the 15th century. The Granet Museum (Musée Granet) houses a cast of a funerary inscription stating “Rabbi Salomon, son of Rabbi David up above in the year [500]2. The Jewish year 5002 corresponds to 1241-42 C.E.

When King René, Duke of Anjou, retired to Aix in 1471, he allowed relative prosperity to the city’s Jews, safe from regional violence and expulsions, in exchange for a large contribution to the city’s finances. Following his death in 1480, King Charles VIII issued a decree expelling the Jews from the province. Nearly 400 Jews lived in Aix before the expulsion, most subsequently emigrating to Comtat Venaissin.

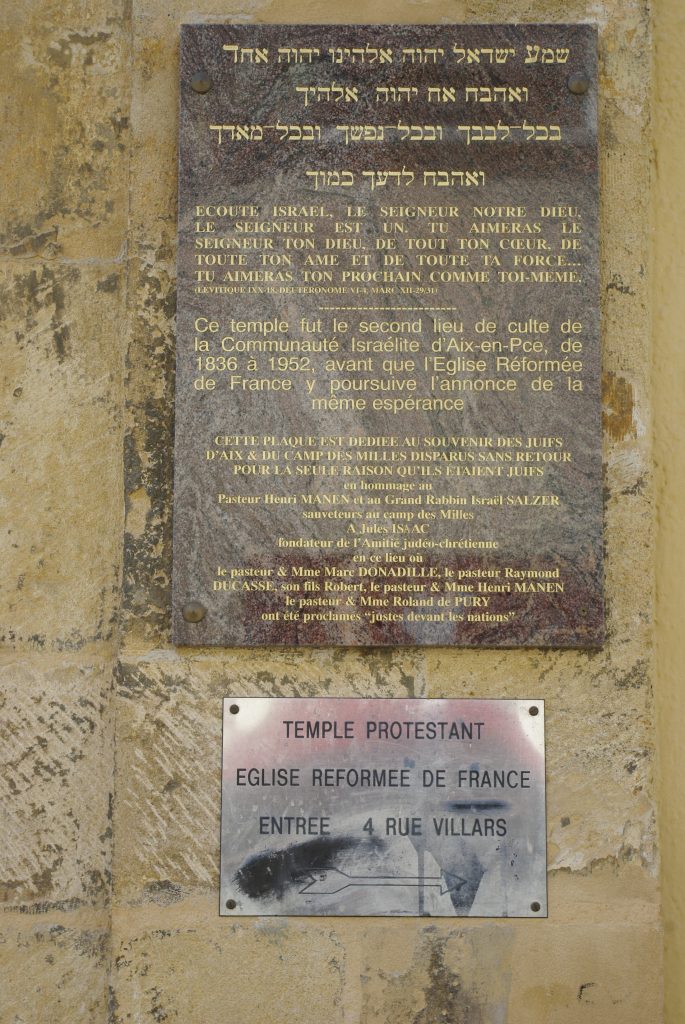

The resettlement of Jews in Aix took place mainly as a result of post-revolutionary emancipation. A synagogue was inaugurated on rue Mazarine in 1840. Many Aix Jews were deported during the Shoah. The few Jews who remained in the city decided to sell the post-war synagogue.

Following the arrival of many Jews from Algeria in the early 1960s, a synagogue was built in rue de Jerusalem. The first stone was laid by the great musician Darius Milhaud, whose grandfather had been president of the community a century earlier.

This synagogue was transformed into the Darius Milhaud Cultural Center in 1997 when a new and larger synagogue was built next door. There are around 2,500 Jews in Aix today.

Other great figures of the city include the mayors of Aix Jasuda Bédarride and his brother Salomon Bédarride, and of course Jules Isaac, a great builder of Judeo-Christian friendship who took refuge there in 1940.

When war was declared in September 1939, the authorities opened an assembly camp in a tileworks in the village Les Milles. Here they assembled foreign nationals from the hostile powers: anti-Nazi Germans and Austrians, Jews, and refugees. Among them were members of the émigré intelligentsia: Max Ernst, Hans Bellmer, Max Lingner.

After the defeat of the French army and the armistice, the camp was turned into a “transit camp” for possible emigrants. Even before the Germans occupied the “Free-Zone” in August-September 1942, the Vichy authorities ordered that some 2000 Jews be deported to Drancy, and from there to the death camps. The camp was closed in March 1943.

The Jewish presence in Marseille dates back at least to the 6th century as is attested by Grégoire de Tours, but probably dates back to the Roman Empire. One of their main commercial activities was to act as an intermediary between Gaul and the Levant. In 576, the Jews of Clermont, victims of the intolerance of Bishop Avitus, took refuge in Marseille, enlarging the Phocaean community.

In the 12th century, two Marseilles communities developed. The first in the lower part of the city, under the authority of the viscount, and the second in the heights, under the dominion of the cardinal.

The traveler Benjamin of Tudela refers to these communities in his accounts. According to him, yeshivot continued to teach in the upper part of the city, and he emphasized their influential presence, dubbing Marseille the city of gaonim (scholars). An opinion shared by Maimonides in 1194, when he noted the presence of great scholars in Marseille.

The lower part of the city, close to the port, favored the influx of merchants, although Jews did little work in the maritime sector. Although they were granted citizen status in 1257, the Jews of Marseille were subject to considerable restrictions.

In the 14th century, the two communities unified, and restrictions were relaxed. There were now three synagogues and a mikveh. Angevin policy enabled the Jews of Provence to flourish, particularly in Marseille. At the time, Jews were very well integrated into the city, taking part in both craft and agricultural production, as well as in coral and livestock farming and in the creation of bastides.

In 1484-1485, the Jewish quarter was attacked. Looting and murder led many to flee. Emigration was limited by the appeasement introduced by the municipality the following year and, a few years later, by the arrival of Jews from Spain as a result of the Inquisition. Nevertheless, a notice of expulsion from Provence was issued in 1500-1501, accompanied by a consequent wave of conversions. As a result, there was no organized Jewish life in Marseille until the French Revolution and the emancipation of the Jews of France.