Tampere is the second largest city in Finland and is located between two lakes.

It is a relatively new city, founded in 1775 by Gustav III of Sweden, with the aim of facilitating trade in the region.

A Jewish community was established in the city in 1947. However, this community, consisting of less than a hundred people, ceased to exist in 1981 due to numerous departures. Only nine members remained. It has not been able to reconstitute itself since.

In the city of Tampere there’s a Jewish cemetery

The Jewish community has existed since Visigothic times and grew considerably under the Muslim occupation.

When the first Christian troops arrived in 1266 under the command of Alfonso X of Castile, there were many synagogues, but most of the Jews preferred to leave the city and take refuge in Granada, which was still in Muslim hands.

A few years later, Alfonso X the Wise sought to repopulate the city and invited the Jews of Castile to come and settle there. 90 families arrived with the characteristic names of Old Castile, castellano, carrion, castro.

In addition to the houses abandoned by the Arabs, they received from the king a flour storehouse, two synagogues, a hospital and a hostel to receive and care for the Jewish refugees and, above all, royal protection.

The heart of the Judería was the current Juderia street, the former synagogue street. The first synagogue was in the street of the same name, the second in the present-day Plaza Santo Angel, but it was destroyed in 1479.

This Jewish quarter was located between the Gate of Seville and the Royal Gate in the current streets of Torneria, Juderia, Eguilaz, San Cristobal, Alvar Lopez, Cuatro Juanes, Plaza del banco and Plaza del Progreso. If the Jews had to live in this area, they worked and traded all over the city and of course around the Market. However, they were obliged to return to sleep in the judería, which closed its doors at night.

In 1391, after the outbreak of violence, the preaching of the Dominicans of the convent of Santo Domingo in the city bore fruit and most of the Jewish population (between 3000 and 9000 people) converted. The Inquisition attempted expulsion in 1483 but without success. In 1492, the Jews left the city and fled to Portugal.

Namur is the capital of the Walloon region and has a great cultural heritage dating back 2000 years.

The Jewish presence in Namur declined from the 19th century onwards, contrary to other Belgian cities which witnessed a development of Jewish life, numbering at most a hundred people. Thus, in 1907, the Jewish community disappeared from Namur.

Documents show that a rabbi and a hazan were present in the 1860s, who worshipped there in a house of prayer. As the population declined, a minyan was no longer possible at the turn of the 20th century and the synagogue was closed for good.

Arlon is a very ancient town, dating back to the Gallo-Roman period.

Since 1831, after the national independence, the Belgian constitution regulates the Jewish cult in the same way as the other recognised religions. Nevertheless, it was not until about thirty years later that the first official synagogues were built and inaugurated. In the meantime, prayers and religious festivals were organised in transitional places. It was not Antwerp or Brussels, but Arlon that hosted the first synagogue, inaugurated in 1865.

The Jewish community of Arlon, whose first members probably settled in the 12th century, numbered 130 people, mainly from Alsace-Lorraine and working as horse and cattle traders. In 1861, given that the house of prayer in the rue de l’Esplanade had become too small, the town of Arlon allocated a plot of land for building and requested the services of the architect Albert Jamot.

Its style was inspired by the synagogues of the Moselle, its exterior façade being the only slightly distinctive element. Tables of the Law crown its triangular pediment. Despite this momentum, the Jewish community of Arlon did not grow as much as those of Brussels, Antwerp and Liege.

Following the Shoah, which claimed many victims among the Jews who were unable to join France, survivors tried to rebuild Jewish life there. A monument in the Jewish cemetery of Arlon commemorates the victims of the Shoah. This cemetery, which dates from 1856, is the oldest in Wallonia still in use and the only one, together with the Dieweg cemetery in Brussels, which contains graves from the 19th century.

By the turn of the 21st century, there were only about 40 Jews left in Arlon. The synagogue was closed in 2014 for restoration and opened on Rosh Hashanah 2019, when Rabbi Jean-Claude Jacob welcomed the congregation. Today it remains a much-visited local landmark.

Sources : Musée juif de Belgique, Consistoire, Times of Israel, Politique et Religion : le Consistoire Central de Belgique au XIXe siècle

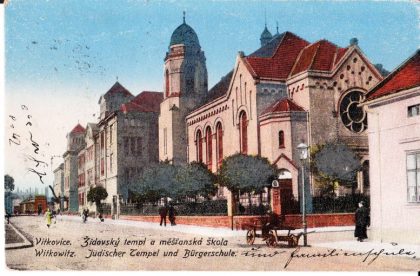

The city of Ostrava is best known for its economic activity. It was one of the great coal mining regions and a major ironworks.

The Jewish presence in the city was rather late, being limited by the local authorities. There are records of a Jewish resident renting a distillery in 1786.

A community was slowly formed, officially taking shape in 1875 with about 60 members. A Jewish cemetery was opened three years earlier.

The industrial revolution had a major impact on the town, especially with the development of coal mining and steelmaking. Many Jews from other towns in Moravia and Galicia settled in Ostrava.

A synagogue was opened in 1879, and there were then just over a thousand Jews in Ostrava. This number increased rapidly to 5,000 in 1900. It doubled in 1937, despite the aliyah in the face of the risk of German invasion, particularly following the arrival of refugees from Galicia and Russia. As a sign of the development of Jewish associative and cultural life in Ostrava, the city had a Jewish school founded in 1919 and hosted the Maccabiades in 1929. The surrounding villages of Frystat, Karvinna, Orlova, Frydek, Mistek and Hrusov also had significant Jewish populations.

During the German occupation, the synagogues in Ostrava and the surrounding villages were burnt down. 1200 Jews were transferred to the Zarzecze labour camp. In all, 3567 Jews were deported and only 253 survived.

A Jewish community tried to re-establish itself after the Shoah. A prayer room was opened in 1978 and a Jewish cemetery was used in Sliezska Ostrava. By the turn of the 21st century there were few Jews left.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Osoblaha is a Silesian village popular with contemporary tourists for its medieval buildings.

The Jewish presence probably dates back to this period and was quite stable over the centuries until the 18th century. Jewish refugees from Vienna and Poland settled here. The Jewish community in Osoblaha included the presence of prominent rabbis.

The number of Jews declined especially at the beginning of the 19th century, due to regional conflicts and threats of expulsion. Most of them moved to the surrounding towns, mainly to Krnov. Thus, only 37 Jews remained in 1921, and the synagogue was demolished twelve years later, with the religious objects transferred to Krnov. The Jewish cemetery was destroyed during the Second World War and restored in the 1950s by the Czechoslovak authorities. In 2019, the cemetery fell victim to vandalism, a phenomenon that is quite rare in the country. 343 graves have been identified, the oldest dating from the late 17th century.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica and JTA

Olomouc was the capital of Moravia from the 14th to the 17th centuries and a major trading town at that time.

The Jewish presence is very old and seems to date from the 11th century. Documents from the Middle Ages have been found which attest to the payment of taxes by the Jews to the local authorities.

The Jews of Olomouc were expelled in 1454 and their property seized. Nevertheless, some Jews were allowed to come to town on weekdays.

It was not until 1848 that the Jewish community was reconstituted, when they were granted equal rights as citizens. A congregation was founded fifteen years later. By the end of the century the town had a synagogue and a Jewish cemetery.

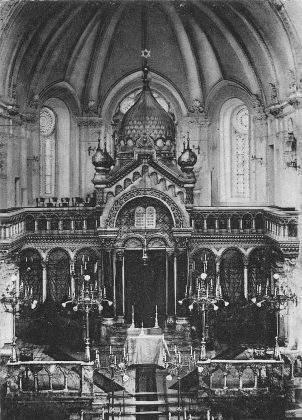

The beautiful oriental-Byzantine synagogue, designed by the architect Jakob Gartner, was opened in 1897. The year the Zionist convention was held in Olomouc, with Theodor Herzl as one of its guests. The Jews participated in the economic development, especially in the malt industry and the cattle trade.

Many refugees from neighbouring regions, especially from Galicia, settled in Olomouc after the First World War. As a result, the Jewish population increased from 2,200 at the beginning of the 20th century to 4,000 at the beginning of the Second World War. During the Holocaust, the majority of the Jews were deported. Only 232 survived. The synagogue was burnt down. A plaque has been placed in Palach Square, near its former location.

In the aftermath of the war, a Jewish community tried to rebuild itself. A Holocaust memorial was installed in the Jewish cemetery in 1949 and six years later a synagogue was opened. A plaque was also placed in 1996 on the primary school in Halkova Street where Jews were gathered during the Shoah before being deported. Today there remains a small Jewish community in Olomouc.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Kojetin is a Moravian town that has been known as a commercial crossroads for centuries and now hosts many cultural events.

The Jewish presence in Kojetin seems to date back to at least the 13th century, although the earliest documents found attesting to this date from 1566. They mention the presence of 52 Jewish families in Judengasse. In the 16th century there was a synagogue and a Jewish cemetery. The synagogue was restored on several occasions, notably in 1614 and 1718.

In the 17th century the town received Jewish refugees from Chmielnicki and Vienna. The Jewish community grew in the following two centuries.

In 1829, 443 Jews lived in Kojetin. The industrial revolution at the end of the 18th century led to many departures, especially of its Jewish citizens.

By 1869, the number of Jews had fallen to 162. This number decreased further to 72 in 1930. Many of them were deported during the Shoah. Some of the texts and objects of worship from the Kojetin synagogue were transferred to the Jewish Museum in Prague in time.

The synagogue is now used as a church. A plaque on the building commemorates the place and pays tribute to those murdered during the Shoah.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Brno is the capital of Moravia. The Jewish presence dates back to at least the 13th century, when the local authorities invited them to settle there without the discriminatory measures imposed in other places at that time.

This warm welcome encouraged development and by 1348 there were almost 1000 Jews living there. Graves from this period have even been found. However, the Jews were expelled from the city in 1454 and were not officially allowed to return until 1848. In spite of these restrictions, the Jews tried to maintain a regular presence and active life in the city, especially in the printing industry with the existence of a publisher of Hebrew texts in the 18th century.

Following the revolution of 1848, the Jews were once again able to live there freely. A synagogue was built in 1855 and a Jewish cemetery three years later. The Jews contributed to the development of the textile industry.

As a result of the First World War, the city took in many refugees from Eastern Europe, considerably increasing the Jewish population of Brno. The Jewish population in Brno increased from 134 in 1834 to 7809 in 1890 and 10202 in 1930. The city’s cultural and academic venues allowed for intellectual development. Many of Brno’s Jews were deported and murdered during the Holocaust. A memorial plaque stands today on the site from where they were deported en masse.

A thousand surviving Jews returned to Brno after the war and tried to revive its community. The orthodox synagogue, which dated from 1932, was restored and reopened in 1968. At the turn of the 21st century, the Jewish community, which consisted of 700 people, decreased to 300. Although small in number, it was active in the management and restoration of synagogues and Jewish cemeteries throughout the Moravian region.

In 2016, a sefer torah was inaugurated in the synagogue, marking the end of a year dedicated to its restoration. Hundreds of people attended the event, including the mayor of the city and the Bishop of Brno. The Jewish community has stabilised over the last twenty years and still consists of about 300 people.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica et Times of Israel

Austerlitz, Slavkov u Brna in Czech, is a town most famous for the Napoleonic battle of 1806.

The Jewish presence in Moravia is one of the oldest, with a Jewish cemetery dating from the 12th century. Among the illustrious figures from the town is the author of the Sefer ha-Minhagim (1294), Moses ben Tobiah. There was also a yeshiva in Austerlitz at that time.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the town had about 60 Jewish families. At the end of the century, the Jewish cemetery was destroyed. The synagogue was destroyed by fire in 1762 and rebuilt through the collective effort of the surrounding communities. A new synagogue was inaugurated in 1857 and a new Jewish cemetery was used fifteen years later, the Jewish population at that time being 544. However, the population declined over time to 66 in 1930. Some managed to escape the Nazi invasion of 1938, but many were deported during the Holocaust.

The synagogue is now used as a Jewish museum and has a memorial plaque to commemorate the victims of the Shoah. There’s also a Jewish cemetery left in town.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Chodova Plana is a town known as an old trade route, for its mines and brewery and the long-standing fights between nobles to rule it.

The Jewish presence probably dates from the end of the 16th century. A synagogue was mentioned in 1645, as well as an ancient Jewish cemetery, where a few hundred graves are located.

Threatened with expulsion on several occasions, a Jewish community continued to live there. About twenty Jewish families lived there in the middle of the 18th century, when a baroque synagogue was built in 1759.

In the following century, the community received the protection and support of Count Catejan of Berchem-Haimhausen (1795-1863), which enabled it to employ a full-time rabbi and to support other social and cultural initiatives.

In gratitude, a plaque in memory of the Haimhausen family was installed in the synagogue. As a result, Jewish life grew throughout the 19th century, reaching a total of 230 people.

A new Jewish cemetery was established in 1890 and was used until the 1930s. Following the annexation of the Sudetenland in 1938 by the German occupiers, the Jewish community was decimated. Only the two Jewish cemeteries in the town remain today.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Zatec is an ancient royal city, dating back to at least the 11th century.

The Jewish presence in Zatec is very old, dating back to at least the 14th century. However, following attacks and expulsion, their official return only took place at the end of the 19th century.

Indeed, only two Jewish families lived in Zatec in 1852. A Jewish cemetery was opened in 1869 and a synagogue inaugurated three years later.

At its peak, the Jewish population was 1,082 in 1921, but declined to 760 ten years later. The community was decimated during the Holocaust.

Zatec is best known in Jewish history for the weapons centre that was built there after the war by American veterans for the purpose of transporting them to support the fearful Israeli yichuv before the War of Independence.

Mostly demobilised aircraft that were refurbished and used to create the Israeli Air Force. A story told in Boaz Dvir’s documentary “A Wing and A Prayer” (2015) by one of its participants, Al Schwimmer, founder of Israel Aerospace Industries.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica & Times of Israel

Votice is a fairly old town in Bohemia.

The Jewish presence dates back at least to the 16th century, with a document from 1538 referring to the town’s Jewish cemetery.

About ten Jewish families lived in Votice at that time. A synagogue was built in 1661 (and demolished in 1950).

About 50 Jewish families lived there at the turn of the 19th century, most of them working as seed merchants, in this town known for its agrarian economy.

By the end of the century, the town and the surrounding villages had 560 Jews.

This population then declined to 76 by 1930. Those who could not flee in time before the Nazis arrived were deported and murdered.

The synagogue and Jewish cemetery were preserved after the war.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Usti Nad Labem is a town of Czech nobility and is known for its chemical industry.

The Jewish presence in Usti Nad Labem dates back to at least the 16th century, but was very irregular, as it was restricted by the authorities. It was not until 1848 that Jews were able to settle there officially. Thus the Jewish population of Usti Nad Labem increased from about 100 in 1880 to almost 1000 in 1930. The community had a place of worship from 1863, as well as a Jewish cemetery.

With the rise of Nazism, most Jews left the town. The few who remained were deported following the Munich Agreement.

After the war, a Jewish community was reconstituted, numbering 800 in 1948. Among the personalities of this period was Ernst Neuschul-Norland (1895-1968) who painted the portrait of the first Czechoslovak president.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Mlada Boleslav is an old Bohemian town that developed in the industrial age thanks to the automobile industry.

The Jewish presence dates back to at least the 15th century, according to written documents of the time. About ten Jewish families lived in Mlada Boleslav in 1570 and had a synagogue. The Jewish cemetery dates from 1584.

The Jewish population was 120 in 1615. They were mainly active in the transport industry. Although they were active in the city, they were also subject to antisemitic attacks. Part of the Jewish quarter and the synagogue were destroyed by fire at the end of the 17th century. A new synagogue was built shortly afterwards, inspired by the Meisl in Prague. It fell into disrepair and was demolished in 1960.

There were nearly 900 Jews in Mlada Boleslav in 1880, but this population declined to 402 in 1910 and 264 in 1930. Most of them lived in the vicinity of the castle.

Very few Jews from Mlada Boleslav survived the Holocaust. Nevertheless, the community tried to reconstitute itself after the war. A line of prestigious rabbis and literary writers remains.

One of the historic Torah scrolls in the Beth Shalom Synagogue in Santa Fe, New Mexico, originated in Mlada Boleslav and dates from the 16th or 17th century. Transferred to Prague by the last remaining members of the community in 1942 for preservation, they were later confiscated, along with 1500 others, by the Nazis. Discovered in 1963 by an expert, the scrolls have been distributed to many Jewish communities around the world. The one in Mlada Boleslav contains letters written by both Sephardim and Ashkenazim.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica & Jerusalem Post

Klatovy is a Bohemian town known for its old markets on the roads to nearby larger towns.

The Jewish presence in Klatovy has been documented since the 14th century, but was not very present in the following centuries until the 19th century. In the middle of the 19th century, Jews, mostly from the surrounding villages, established a community in Klatovy. A synagogue and a cemetery were opened in the 1870s. More than 1300 Jews lived there.

Very active in the economic life of the town, it continued to attract newcomers. Nevertheless, the Jewish population began to decline at the turn of the 20th century.

The synagogue was sacked in 1941 and the Jews of Klatovy deported the following year. Some relics from the synagogue were saved and sent to the Jewish Museum in Prague. The synagogue and the Jewish cemetery were put back into operation after the war. A monument commemorating the Jews of Klatovy deported during the Shoah was erected in the cemetery in 1989.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Carlsbad, Karlovy Vary in Czech, is a city famous for its spa complex and its festival.

The Jewish presence in Carlsbad was “only intermittent” until the middle of the 19th century, being forbidden to stay there and mainly coming to work occasionally from surrounding villages. Others came on holiday. The Jewish communities in Vienna, Prague and Berlin contributed to the creation of a holiday centre for disadvantaged families in nearby Marienbad.

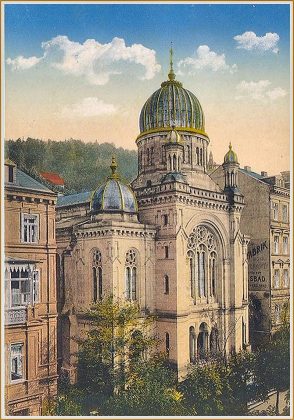

Authorised by the municipality to form a community in 1868, the Jewish population grew rapidly, from 100 in that year to 1600 in 1910 and 2120 in 1930. Among the influential families were the Mosers, who founded a famous glass factory.

A synagogue was opened in 1877, its most famous rabbi being Ignaz Ziegler, who officiated from 1888 to 1938. He managed to escape during the German invasion and ended his life in Jerusalem. The synagogue was destroyed in 1938 and most Jews managed to leave the city in time. The city hosted the 12th and 13th Zionist Congresses in 1921 and 1923 respectively.

The Jewish community re-created itself in Carlsbad after the war, numbering about 400 people. It built a community centre with a synagogue, library and mikveh. Carlsbad also has a Jewish cemetery.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica & Times of israel

Benesov is a town in Bohemia, whose name is derived from its medieval rulers.

The Jewish presence dates back to at least the 15th century, making it one of the oldest in the region. Nevertheless, the community consisted of only a handful of members until the middle of the 19th century.

In 1893, the Jews of Benesov and the surrounding villages numbered just under 800 people. The number declined to 237 in 1930.

Today, there is no longer a community present in the area. Relics from the Benesov synagogue have been preserved in the Jewish Museum in Prague. Two Jewish cemeteries can be visited today. Few gravestones remain, some of them having been used for road construction.

The ancient Jewish cemetery is located near Nova Prazka Street and dates from the end of the 17th century.

The newer Jewish cemetery is located 500 metres north of Masaryk Square in the municipal cemetery. Founded in 1883 and used until the Second World War, it contains about 300 graves. These were restored in the 1990s.

A monument commemorating the victims of the Shoah was installed there.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

Bechyne is a fortified town in the Bohemian region near the Luznice River. It dates back to the Middle Ages and was an important regional centre. It is best known today as a thalassotherapy centre.

The Jewish presence in Bechyne dates back to at least the 16th century, as evidenced by administrative documents showing a conflict of interest. The Jewish community consisted of 81 people in 1715 and only 56 ten years later.

Following an increase in the next century, it reached 145 members in 1902, but only 32 in 1930. The community was decimated during the Holocaust and only a few period houses on Siroka street (including a former synagogue turned into a museum) and the Jewish cemetery, dating from the early 17th century, have been preserved. Among the steles are some amazing baroque sculptures.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica

The second largest city in the Veneto region in terms of economic activity, Verona is also known for its beautiful ancient cultural and religious buildings and its university.

The first documents that attest to a Jewish presence in Verona date from the 10th century, in reference to a desire to expel them. These documents indicate names of German origin. Among the Jewish personalities in Verona in the Middle Ages were the poet Abraham ibn Ezra, the rabbi Eliezer ben Shmuel and the Talmudist Hillel ben Shmuel.

After some back and forth due to the different degrees of tolerance of the local authorities, the Jews were recognised as citizens by a decree in 1406.

This was on the condition that they were obliged to practice the profession of pawnbroker and to live in the ghetto of the San Sebastiano district. A synagogue was built at that time near the Piazza delle Erbe.

In the 16th century they were given the opportunity to diversify their economic activities. Thus, Jews were found in the trade and sewing sectors in particular. They were also able to move to other parts of the city. In the middle of the 16th century there were about 400 Jews in Verona.

However, at the end of the 16th century they were forced to return to a ghetto, still near Piazza delle Erbe, between Via Mazzini and Via dei Pelliciai.

The arrival in the 17th century of Sephardic Jews from Venice and the Iberian Peninsula led to the creation of another Jewish community, with its own synagogue, in the same area as the first. Despite their different rites and origins, the two communities were founded around a single synagogue in 1675. At the end of that century, there were 900 Veronese Jews.

When Napoleon’s troops arrived in 1797, the walls of the ghetto were demolished, but the Jews had already left the area in large part, a sign of their inclusion in the economic and social life of Verona. But also in the cultural life with the musicians Giacobbe Bassini Cervetto and his son Giacomo.

However, the community began to decline at the end of the 19th century. By 1909 there were only 600 Jews, and by 1931 there were 429. 31 Veronese Jews were deported and murdered during the Shoah. A plaque in their memory has been placed on the synagogue in Via Portici. Today the Jewish community consists of about 100 members.

The former Jewish cemeteries were in Campo Fiore and Porta Nuova. The present Jewish cemetery is located in Borgo Venezia.

Sources : Veneto Jewish Itineraries by Francesca Brandes and Times of Israel

Close to Venice, Treviso is a city known for its commercial activities and its agricultural production, especially in wine and horticulture.

The documents that attest to the Jewish presence are very old, dating from the 10th century. They mention the presence in Treviso of a Jewish family, originally from Germany, with shops in the town.

Nevertheless, few documents are found in the following centuries of the Middle Ages. They mainly concern the activities of pawnbrokers, often one of the only professional activities during this period, with more or less possibility to diversify according to the prevailing spirit of tolerance. They suffered religious and financial discrimination, resulting in expulsion in the 16th century.

Jews lived mainly in the area around Via Portico Oscuro, where there was also a synagogue and a mikveh, as well as a prestigious yeshiva. The Jewish community had a cemetery since at least the 15th century in the Borgo Cavour area, where the Municipal Museum is now located. Twenty-seven Jewish tombstones were discovered in 1880 during excavations near the wall of San Teonisio. These gravestones are currently stored in the Ca Da Noal palazzo area.

The modern Jewish cemetery dates from the 19th century and is included in the municipal cemetery of San Lazzaro. At that time a small Jewish community was reconstituted but is no longer in operation.

Sources : Veneto Jewish Itineraries by Francesca Brandes and Encyclopaedia Judaica

Piove di Sacco was built in Roman times and fortified in the Middle Ages. The Jewish presence is attested by documents dated from the end of the 14th century. They concern the arrival of Jews who were involved in banking, which was often the only activity permitted for them at the time.

This did not prevent them from pursuing other interests, such as Moshe ben Samuel, a banker and scribe who worked on Maimonides’ work. A passion for writing shared by many of his fellow citizens. Like Meshulam Cusi, a rabbi who lived in Este from 1468 to 1474 and who had set up a printing house in Veneto.

In particular, he published books of Slikhot and above all the second book published in Hebrew in Italy, Arbaa Tourim by Jacob ben Asher, which is now in the Civic Library of Padua.

This activity made Piove di Sacco the main place for printing Hebrew texts, until it was dethroned by Venice in the 16th century.

Other rare works can be found today in the University Library of Turin and the National Library of Madrid. It was in the Stradella della Stamperia that this printing house, one of the oldest in Europe, seemed to be located.

Proof of the integration of the Jews, who came out of the ghettos, in the 19th century, some of them were elected to parliament. Isacco Vita Morpurgo in 1864 as a town councillor. Leone Romanin Jacur was elected to parliament eleven times.

Sources : Veneto Jewish Itineraries by Francesca Brandes and Encyclopaedia Judaica

Este is a very old town, which served as a military base and was rebuilt around a castle following a destruction. It reached its peak during the Venetian era. Documents dating from 1389 attest to the settlement of Jews in Este in order to open a banking institution.

A Jewish ghetto was established in 1666, in the San Martino district. It consisted of only a few houses and was accessible through a single entrance. As a sign of a relatively peaceful life, Emilio Morpurgo was elected several times to the Parliament of Este-Monselice. On 8 September 1943, the Jews of Este were arrested and sent to concentration camps, ending their presence in the town.

It seems that a Jewish cemetery in the neighbourhood of San Pietro was used as early as the end of the Middle Ages, but no trace has been found. A second cemetery was used between the 17th and 19th centuries in Via Olmo. Some gravestones have been preserved.

Sources : Veneto Jewish Itineraries by Francesca Brandes

A relatively new town for the region, Urbania was built under the name of Casteldurante in the Middle Ages and then adopted its present name in memory of Pope Urban VIII.

Documents dating from 1437 attest to the Jewish presence in the town. Although the Jews were initially forced to work as pawnbrokers, they soon diversified. Some opted for those related to trade or and others to weaving and crafts.

Despite some threats against them, the Jews contributed to the active life of Urbania throughout the 16th century. Nevertheless, relations between Christians and Jews deteriorated at the end of the century.

The duchy fell under the rule of the Papal States in 1633 and the Jews were forced to gather in the ghetto and preferred to leave the city. Temporarily allowed to carry out certain professional activities on local fair days, the Jews only settled in Urbania again at the end of the 19th century, when the city joined the Kingdom of Italy.

As a sign of good integration, one floor of the house of Samuele Moscati, a Jew from Urbino, was used as offices and courtrooms. A building at the entrance to the city, by the Ponte del Riscatto, is called Palazzo degli Ebrei. The synagogue seems to have been located at 17 Via Garibaldi.

Sources : Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni.

San Severino is a Roman town, with architectural traces of the different periods, especially the medieval and Renaissance ones. Administrative documents attest to a Jewish presence dating back to at least the 13th century.

The Fonte dei Giudei, literally “the fountain of the Jews”, built in 1295, is a sign of this antiquity. It has since been renamed Fonte del Casale.

From the 14th century onwards, their economic activities were regulated by the local authorities and their freedom of worship was guaranteed. They were granted a piece of land that could be used as a Jewish cemetery. Not limited to the trade of pawnbrokers, they were able to diversify and practise all sorts of professions. These included cattle trading, crafts and medicine.

Nevertheless, in 1555, the Jews were forced to live in a ghetto in the San Lorenzo district, near the church of San Rocco. Expelled from San Severino in 1569, the Jews could only return for specific economic activities related to the local fairs.

Sources : Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni.

Recanati is best known for being the birthplace of the poet Giacomo Leopardi, whose name is also very present on the monuments. In particular, Piazza Leopardi with its monument to the poet.

The first documents attesting to a Jewish presence in the city date from 1336 and 1343. The names of Jews who practised the profession of pawnbroker seem, according to these same documents, to have joined an already existing community.

This is also symbolised by the existence in the last century of the cabalist Menahem ben Benjamin Recanati, as Jews often took the surname of their town of origin or their profession as their family name. Other famous people with this name include Leon Recanati, an Israeli businessman and philanthropist, and Lenny Recanati, founder of the wines that bear his name.

When they were allowed to do so, the Jews diversified their professional activities, especially in commerce and medicine, where, unusually in the 15th century, two women also practised this profession. There was a synagogue near the bishop’s palace.

Following the papal bull of 1555, the Jews had to leave Via Vicolo Sebastiani and its surroundings. This, in order to be placed in the ghetto was created in the Monte Volpino area, where the present Piazza Bianchi is located, extending to Via Achille, where a synagogue was apparently located at number 1 of the street.

Most of the Jews left Recanati in 1569, settling mainly in the towns of Ancona, Fossombrone and Pesaro.

The Jewish cemetery was located in Campo dei Fiori, near the Cathedral of San Flaviano. A stele with Hebrew inscriptions is in the Diocesan Museum.

Sources : Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni.

The city of Osimo is a strategically important place and has been the victim of numerous conquests by regional powers over the years. This is evidenced by the very old buildings, churches and imposing palaces.

The oldest written evidence of the Jewish presence in Osimo is a document from 1302, which describes their life in the city. At that time they lived mainly in the San Gregorio district. Authorised to settle there for professional activities related to loans, they diversified their commercial activities. In particular in import-export, weaving and crafts.

The Jewish population increased in the 16th century. About thirty Jewish families are mentioned in documents of the time, but there is no written record of a synagogue. This suggests that they prayed in an oratory in a private house. In the 1540s the climate deteriorated, with forced conversions and departures from the city. Following the papal bull of 1555, a ghetto was established in Osimo. It appeared to be located in Via Santa Lucia. However, few traces of it remain due to the successive building constructions undertaken from the 17th century onwards. Discriminatory measures were imposed on the Jews, in their professional and personal life, in their relations with the Christians. In the middle of the 16th century the Jewish population started to decline.

The Jews were expelled in 1569. Among them was Rabbi Jeudah ben Joseph Moscato. Born in the city, he was one of the leading cabalists of the Renaissance. He settled in Mantua, becoming the rabbi of his community. Some returned at the turn of the century following the easing of discrimination and announcements to that effect. However, in 1646 it was decided to prohibit the arrival of new Jewish citizens.

Another Jewish personality who left his mark on the region was the sculptor Vito Pardo. He was the creator of the work commemorating the Battle of Castelfidardo, which is located in a park north of Osimo. Many Jews bear the surname Osimo. Among them is Bruno Osimo, a translator born in Milan.

Sources : Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni.

The town of Monterubbiano is situated at a high altitude and is very old, predating the Roman period. The medieval part of the town is still significant, as evidenced by its buildings, numerous churches and its archaeological museum.

The Jewish presence in Monterubbiano dates back to at least the 13th century. In contrast to the limited professional situation of their co-religionists in many other towns, the Jews were able to enter various professions. These included weaving and leather.

At first they lived in different parts of the city such as Contrada San Giovanni, San Basso and San Nicolo. In 1555, the latter became the Jewish ghetto. The old synagogue is believed to have been located in the present Via Garibaldi, at number 28.

Sources : Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni

A medieval town, Mondolfo was famous for its castle built by the architect Francesco di Giorgio Martini, which was destroyed in the 19th century. The town was also an important economic and cultural centre over the centuries.

The fire that destroyed the municipal archives in 1517 makes it impossible to know exactly when the Jewish presence in Mondolfo began. A commercial transaction between the municipality and a Jewish person is mentioned in 1520.

There are records of the presence of Jews in the area near the old Via Giraldi Della Rovere, now called Via Fratelli Rosselli. In this street one can still see some very old buildings. One of them with two entrances was probably an old synagogue and connects with Piazza del Comune.

The situation of the Jews improved at the end of the 16th century, especially during the reign of Francesco Maria II (1549 – 1631), who was the last Duke of Urbino. When the Duchy came under the control of the Papal States in 1625, many of the Jews of Mondolfo migrated to the ghettos of Pesaro and Senigallia.

Sources : Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni

Mondavio is a very old town and was the main town of the diocese of Fano in the 14th century. Its castle, built at the end of the 15th century, testifies to Mondavio’s important place in regional civil affairs as well.

The first mention of the Jewish presence dates from 1349. Two Jewish names appear in the Libro dei Nobili e degli uomini d’entrata, a sort of mixture of Who’s Who and the Yellow Pages of the time where nobles and members of the commercial life are listed.

Documents showing the taxes paid by all citizens show that the Jews, like the rest of the local population, were part of all social classes. As in many small towns in the region, the life of the Jews became more complicated over the centuries. So they gradually left in the 16th and 17th centuries.

At the end of Via Mazzini you come to Via Borgo Mozzo where the Jews of Mondavio lived.

Sources : Marche Jewish Itineraries by Maria Luisa Moscati Benigni