It is known that there was a Jewish community in Inca at least since Jaume I conquered Mallorca in 1229. That said, their presence had been mentioned before by Severus, bishop of the island in the fifth century.

The Jewish quarter of the city (call) dates from 1346 and was established by a decision of Peter IV of Aragon, on a request from the governor of Mallorca, after the repeated complaints of the Christian community, indisposed by the Jewish presence in the city.

The construction of the call did not calm the Christian population. Attacks against the Jews were reported in 1372. In 1391, the Jewish houses and businesses of the city were burned by the populace. This event marks the end of the call and most survivors convert to Christianity.

In all likelihood, the call had a synagogue. Indeed, in a document of 1392, the convert Bortomeua asks for inheritance rights on a property that belonged to his grandfather “Jucef Ben Baharon, rabii of the Jewish school of call”. The location of the call is today between Sant Francesco, Virtut, Can Valella, Pare Cerdà, El Call, and La Rosa Streets. It is estimated that about 306 Jews lived there, for the majority of traders and artisans.

The Can Moroig house is located at 22 Carrer de Can Valella and is also called Can Móra. The building is at the heart of the old call and has consequently been identified as an old Jewish home. The one-storey house dates from the early 16th century. Its facade made of small stones is similar to other houses in the neighborhood. Unoccupied for years and deteriorated by the passage of time, the house was bought ten years ago. The renovation undertaken by the owners has revealed multiple architectural elements that prove its medieval origin, including the Gothic arches. Further excavations have revealed that the foundations of the house date back to the 14th or 13th century. An oven and a wine cellar were discovered, as well as, in the courtyard, a cistern decorated with anthropomorphic decorations – there are two eyes and one nose. The house can be visited.

Jews settled in Arad in the early eighteenth century, reaching the number of 10,000 before the Second World War. In the nineteenth century, this city was one of the hearts of Reform Judaism, under the direction of Rabbi Aaron Chorin.

The community survived the Holocaust and most of the family emigrated to Israel after the war. There are less than 300 Jews in Arad today. Community life is organized around the synagogue, the cemetery, but also the kosher canteen, the retirement home and the airy center. Before your trip, you can contact the Jewish community of the city.

The neologic synagogue of Arad

The first Jew to officially settle in Arad was a merchant named Isac Elias, who became the founding member of the Jewish community in 1742. Other historical documents mention a woman named Nahuma; who would have donated a plot of land for a synagogue. The first place of worship of the city, a wooden building, was born with the community in 1742.

In 1828, the synagogue had 812 faithful and therefore became too narrow for this thriving community. The synagogue we know today, of Greco-Tuscan style and imagined by the architect Heim Domokos, is built from 1827 and inaugurated in 1834. The neologic synagogue of the city entered the patrimony of Arad in 2004. Three stories high, it was built in a triangle, an unusual form at the time. Access to the building is via a small courtyard in the center of the building.

The town of Trancoso is an ancient city at the crossroads of many wars, and as such was transformed into a fortress. The Jewish presence probably dates back to the 12th century. Its population soon increased as a result of the Spanish Inquisition, mainly due to the arrival of Jews from Aragon and Castile. As a result, the community asked King John II for the right to expand the synagogue.

The medieval town of Trancoso is very strongly marked by its Jewish past. Indeed, throughout the Middle Ages, the community of this city in northern Portugal has experienced an economic and social expansion almost unique in Europe. Trancoso, thanks to its important fair, was a city of passage and exchange.

In the fifteenth century, the Jewish population rose to more than 500 people, which forced the community to settle outside the boundaries of the judaria. Even today, there are many traces of this past in the streets of Trancoso. Following the establishment of the Inquisition in Portugal, many of Trancoso’s Jews fell victim to persecution.

As you walk through the city, you will find Hebrew inscriptions, stars of David, and other symbols on the door jambs. Leave the El Rei Gate and go to Corredoura Street and São João Street. In Estrela street you will also find inscriptions. In Banderra Street, a candlestick carved in stone. In Largo Luís de Albuquerque, admire the most famous Jewish house in the city: Casa de Gato Preto (the house of the black cat). A lion of Judah and the walls of Jerusalem are carved around the door. It is likely that this house belonged to the rabbi of the community, or even that the building housed the synagogue. Continue your way to Algria and Mercadores streets, and finally to Cavaleiros street where there is an engraved Star of David. On Dinis Square, where in the 1980s a roll containing Shema Israel was found in a house in a wall.

Finish your visit with the Jewish Cultural Center Isaac Cardoso. Founded in 2012, this space, designed by the architect Gonçalo Byrne, hosts, in addition to the center, the Beit Mayim synagogue, a garden, two temporary exhibition halls, a conference room, and a courtyard where found a well and Hebrew inscriptions. In the Center, you will have access to archives on the history of the 700 Jews of Trancoso persecuted during the Inquisition. The center also catalogs all the inscriptions found in the city, to date 300 in number.

A great scholar of Trancoso: Isaac Cardoso

Isaac (Fernando) Cardoso was a physicist, philosopher, and Jewish writer. He was born of marrano parents in 1603 or 1604 in Trancoso, and died in Verona in 1683. He was the brother of Abraham (Miguel) Cardoso.

After studying my medicine, philosophy, and natural sciences in Salamanca, he moved to Valladolid in 1632, then to Madrid. Among the works he published in Spain, there is a treatise on Vesuvius, the color green or cold water.

Born Fernando, he leaves Spain, probably to escape the Inquisition, and exiles with his brother Miguel in Venice. The two brothers re-adopt Judaism and change their names for Isaac and Abraham. He died in Verona, recognized and esteemed by Jewish and Christian communities.

Cardoso published in Venice in 1673 the treatise Philosophia Libera in Septem Libros Distributa, in which he affirmed himself as a declared enemy of the Kabbalah and the false prophet Sabbatai Zevi – his brother was a partisan.

Finally, the most important work of this “God-fearing scholar”, as described by Moses Hagiz, is Las Excelencias y Calunias de la Hebreos, printed in 1679 in Amsterdam. In this book, he defends the “excellence” of his associates: their selection by God, their separation from other peoples through special laws, their compassion, philanthropy … He then refutes the “slanders” that are made to them: ritual killings, false idols, blasphemy of sacred images … This treaty made a great noise for its publication, and was celebrated by the greatest rabbis and scholars of Europe.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, Rede de Judiarias

The Jews lived under Arab occupation in Malaga from 743. They settled in the neighborhoods on the periphery in the company of the very active traders of Genoa. At the fall of the caliphate of Cordoba, the city hosted many Jewish refugees, including Samuel Ibn Negrella who then began his meteoric rise and later became the advisor to the Arab kingdom of Granada. In the eleventh century, there were 200 Jews in Malaga. In 1487, after the conquest by the Catholic Kings, the population of 450 Jews was deported to Carmona. The Jewish communities of Castile payed a ransom to release them. Abraham Senior and Meir Melamed were responsible for raising the money. Once released they returned to Malaga but will be five years later expelled to North Africa.

The judería is at the foot of the Alcazaba Fortress. A small set of streets: Granada, Zegri, Santiago, gives us an idea of Jewish life. In Postigo Street of San Agustin was the synagogue. In the 1970s on this site was erected a monument to the poet Solomon ibn Gabirol born in Malaga around 1021.

The Jewish community was reconstituted in the twentieth century with the arrival of many Jews from northern Morocco, Ceuta and Melilla. In 1950, there were 250 Jews, in 2000, about 1500. There is a modern synagogue with all services: primary school, kosher butcher, cemetery.

In 1610, the city fathers of Rotterdam issued permits to engage in trade within the city to a small number of Portuguese Jewish merchants. The permits guaranteed freedom of worship and the right to build a synagogue and establish a cemetery. In 1612, these provisions were challenged by the local Remonstrant Church. This prompted a number of Jewish families to depart Rotterdam for Amsterdam. Those Jews who remained in Rotterdam prayed together in the attic of a private home and buried their dead in a cemetery in Rubroek, located in what later became Jan van Loonlaan street. A second group of Portuguese Jews arrived in Rotterdam in 1647. Their numbers included a forefather of the De Pinto family.

In 1647, the city council of Rotterdam awarded local Jews all of the rights enjoyed by their coreligionists in Amsterdam. The Rotterdam Jewish community grew quickly thereafter and soon opened a synagogue in a house at the corner of Wijnhaven and Bierstraat. The community also founded a school for the study of Talmud, the Jesiba de los Pintos (the Yeshiva of the Pintos). The school moved to Amsterdam in 1669. During the second half of the 17th century, most of the leading Portuguese Jewish families in Rotterdam engaged in international trade.

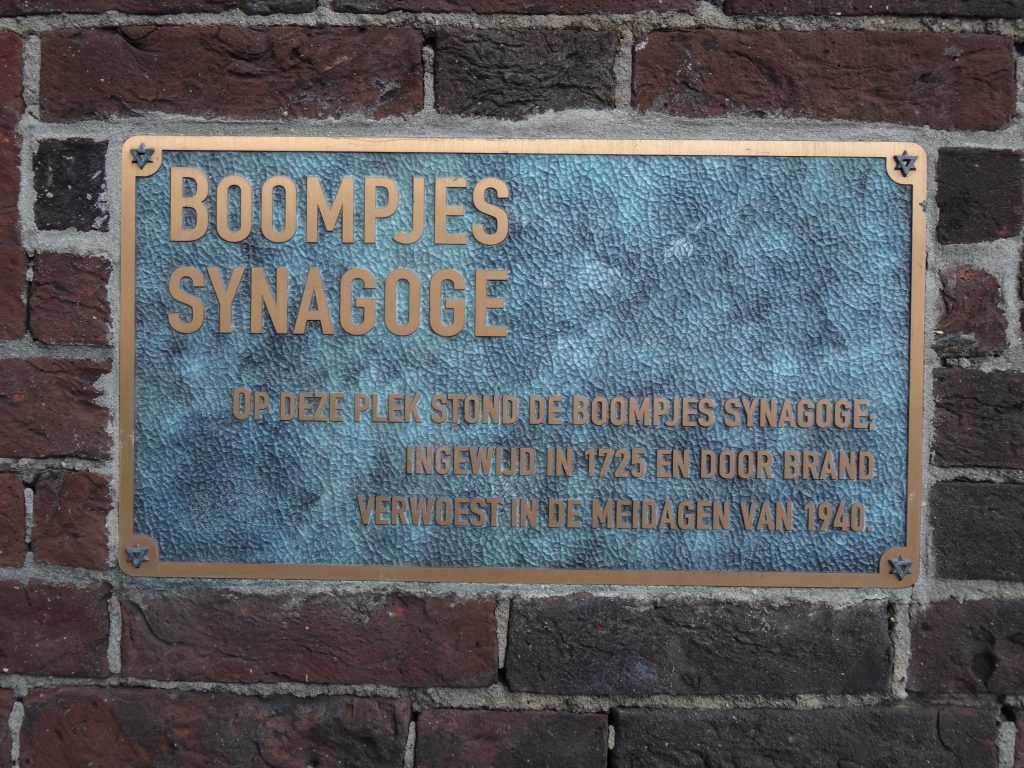

During the final decades of the 17th century, the community’s synagogue was moved from Wijnhaven street to new quarters on Scheepmakershaven street and then on De Boompjes street. The Jewish cemetery was filled to capacity in 1693; soon after, the Portuguese community opened two new cemeteries one after another in the Crooswijk quarter. The newer of the two, located on Oostzeedijk, street was transferred to the Ashkenazi community of Rotterdam during the 17th century.

Membership in the Portuguese-Jewish community declined over the first decades of the 17th century. By 1736, the community ceased to exist. Thereafter, the few Portuguese Jews who remained in Rotterdam attached themselves to the Ashkenazi community.

Ashkenazi Jews had arrived in Rotterdam from Germany and Poland during the mid-seventeenth century. By the 1660’s, their numbers were large enough for them to organize a community of their own. By the 1670’s, the Ashkenazim of Rotterdam had their own rabbi, synagogue, and cemetery. The synagogue, located on Glashaven, street was consecrated in 1674.

In the eighteenth century, the Ashkenazi community grew in size and the Portuguese community declined. By the end of the seventeenth century, the Ashkenazi community had outgrown its first synagogue and, in 1702, replaced it with a new synagogue nearby. That synagogue was soon replaced by the synagogue on De Boompjes which was consecrated in 1725.

The basement of the synagogue on De Boompjes contained a hall for the celebration of festivities. The kosher butcher shop of the Ashkenazi community was located behind the synagogue. In 1784, an annex synagogue was built adjacent to the rear of the synagogue. The structure fell into disrepair and was replaced with a new annex fifteen years later. At the time, the majority of Jews in Rotterdam resided in the immediate surroundings of the De Boompjes synagogue.

The Ashkenazi community of Rotterdam founded a Jewish school in 1737. The same year, the community opened a new cemetery on Dijkstraat street in the present-day quarter of Kralingen. The Kralingen cemetery was expanded several times and remained in use until the opening in 1895 of a new cemetery located on Toepad street in Rotterdam. This cemetery remains in use today. Another Jewish cemetery also existed in the town (now quarter) of Delfshaven.

At the end of the eighteenth century, 2,500 Jews lived in Rotterdam, the largest Jewish population in the Netherlands outside of Amsterdam. At the time, the majority of the Jews residing in Rotterdam worked as small retailers or traders. The exclusionary practices of local guilds insured that the economic status of most of the city’s Jews remained poor. The granting of full civil rights to Jews in 1796 caused this situation to gradually change. Newly found civil equality also occasioned a number of conflicts within the Jewish community. Beginning in 1814, under the reign of King Willem I of the Netherlands, the Jewish community at Rotterdam confirmed its regional importance by being named as the seat of the provincial chief rabbinate.

The Jewish population of Rotterdam grew fourfold over the course of the nineteenth century. This was mainly due to the economic emergence of Rotterdam, which attracted many Jews to the city. Their numbers were augmented by Eastern European Jews emigrating to America via the port of Rotterdam, quite a number of whom chose to remain in the city rather than travel onward.

Although the economic emergence of Rotterdam attracted Jews, poverty remained rife amongst the city’s Jewish population. Jewish voluntary and social organizations bloomed as the city’s Jewish population expanded. Priority was given to Jewish education and the education of the children of the community’s poor. Rotterdam Jews maintained burial societies, societies for aiding the sick, travelers’ aid societies, and societies providing aid to orphans and the elderly. Religious organizations proliferated, and, on the secular front, the Jews of Rotterdam maintained a wide variety of social and political organizations as well as sport and recreational clubs.

The nineteenth century also witnessed the ongoing integration of the Jews of Rotterdam into public society at large. Jews participated in municipal affairs and also became active in the press, legal affairs, education, and medicine. Many Rotterdam Jews rose to the tops of these fields.

As the Jewish population of Rotterdam left traditional Jewish neighborhoods and began to reside throughout the city, a number of small new synagogues were founded. A separate Portuguese Jewish community came into existence in Rotterdam during the middle of the nineteenth century but maintained itself only for twenty years. During its brief revival, the Portuguese community had a synagogue and cemetery of its own in Crooswijk. In 1891, the Jewish community of Rotterdam opened a new central synagogue located on Botersloot. The central synagogue building was restored in 1939 and, in the same year, became home to the community’s archives.

As the end of the nineteenth century approached, tensions emerged between conservative and liberal factions of the community. Jewish newspapers arose reflecting such splits. Following its founding in 1908, the Nederlandse Zionistenbond (Union of Dutch Zionists) exercised a strong influence on a portion of the Rotterdam community.

During the first decades of the twentieth century, the growth of Jewish Rotterdam peaked. A number of small synagogues continued to be built, including the Lev Jam synagogue, located on Joost van Geelstraat and inaugurated in 1928. The arrival of large numbers of German Jewish refugees in Rotterdam during the 1930s caused the ranks of the community to swell anew. A portion of the newly-arrived refugees was placed by the Dutch government in a camp located at Hoek of Holland (west of Rotterdam).

The German bombardment of Rotterdam on May 14, 1940, laid waste to the center of the city and destroyed the synagogues on De Boompjes and Botersloot. Under the German occupation of the Netherlands during the Second World War, the Jews of Rotterdam suffered under the same measures as Jews throughout the country. Jewish children were expelled from Rotterdam’s public schools in September, 1941. The community then founded separate Jewish schools as well as establishing a network of social organizations. An attempt was also made to continue the religious life of Jewish Rotterdam.

Deportation of Jews from Rotterdam began in July 1942 and ended in June 1943. Almost all of Rotterdam Jews were forced to assemble for deportation in the harbor of the city, at Loods 24. Before the war was over, most of the Jews of Rotterdam perished in Nazi death camps. Only 13% of the Jewish population of the city survived the war.

After the war, Jewish life in Rotterdam arose anew with the Lev Jam synagogue as its center. In 1954, a new synagogue, the A.B.N. Davidsplein, was consecrated. A Liberal Jewish community was founded in Rotterdam in 1968. The Liberal community shares a cemetery in Rijswijk with the Liberal Jewish community of The Hague.

A monument to the Jews of Rotterdam murdered during the Second World War was unveiled in 1981 in the garden of Rotterdam’s city hall. A monument to the deported was unveiled at the site of Loods 24 in 1999. The entranceway to the former Jewish hospital on the Schietbaanlaan was restored in 2001 and now serves as a memorial monument as well. In April 2013, a monument for the 686 deported Jewish children was unveiled at the Stieltjesstraat, next to the Loods 24 site.

Source: Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam

Several Jewish families settled in Veghel during the 18th century (around 1731) despite the opposition of local authorities. Most of the Jews who settled in Veghel came to the village from nearby Nistelrode or Dinther. During the second quarter of the 19th century, an organized Jewish community was established in Veghel.

The community at Veghel opened a synagogue on the Achterdijk, the present-day Deken van Miertstraat, in 1832. The synagogue was restored in 1866 with the help of a subsidy from the village council. The synagogue was renovated anew in 1930 and again in 1938.

In 1886, as the Jewish population of Veghel approached its peak, a Jewish school was built on the Bolkenplein. This same square housed a kosher meat market. The school’s teacher also served as the community’s cantor and ritual slaughterer. At the time, the community was governed by a board consisting of three members. The board also supervised religious education. Other community officials included a treasurer for the collection and disbursement of funds to the Jewish community in Palestine. Voluntary organizations included a burial society and a society for the maintenance of the synagogue. The international Jewish relief organization Alliance Israélite Universelle maintained a branch in Veghel. The Jewish community of Veghel, together with those of Sint Oedenrode and Uden, buried its dead at the Jewish cemetery in Schijndel.

During World War II, almost half the Jews of Veghel were deported and murdered. The remainder escaped abroad or survived the war in hiding. A local organization made it possible for approximately 20 Jewish children to hide in the surroundings and escape deportation and death. Some of the Torah scrolls and ceremonial objects from the Veghel synagogue were taken to Amsterdam and hidden; the remainder was robbed by the Germans. A few silver objects buried for safekeeping in the garden of the synagogue also were recovered after the war.

Of the 13 Jewish families living in Veghel prior to the war, only three returned. The Jewish community at Veghel was administratively dissolved in 1947 and the locale placed under the jurisdiction of the Jewish community at Oss.

Restoration of the ancient synagogue on the Deken van Miertstraat was finished in 2002. In 2003, a plaque inscribed with a biblical passage (Isaiah 56:5) in memory of the murdered Jews of Veghel was affixed to the wall of the building. A memorial stone at the Jewish cemetery at Schijndel is inscribed with the names of Jews from the surroundings murdered during the war. The former synagogue now houses a lunchroom.

Source: Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam

Archaeologists have discovered an oil lamp dating from the 4th century. A menorah was found on it. Documentary evidence of Jews living in Augsburg dates from 1212. Records from the second half of the 13th century show a well-organized community, and mention the Judenhaus (1259), the synagogue and cemetery (1276), the ritual bathhouse, and “dancehall” for weddings (1290).

Development and persecutions

The Jews were mainly occupied as vintners, cattledealers, and moneylenders. Until 1436, lawsuits between Christians and Jews were adjudicated before a mixed court of 12 Christians and 12 Jews. In 1298 and 1336 the Jews of Augsburg were saved from massacre through the intervention of the municipality. During the Black Death (1348–49), many were massacred and the remainder expelled from the city. The emperor granted permission to the bishop and burghers to readmit them in 1350 and 1355, and the community subsequently recovered to some extent.

Later, however, it became so impoverished by the extortions of the emperor that the burghers could no longer see any profit in tolerance. In 1434–36 Jews in Augsburg were forced to wear the yellow badge. The community, then numbering about 300 families, dissolved within a few years; by 1340 the last Jews had left Augsburg. Thereafter, Jews were only permitted to visit Augsburg during the day on business. They were also granted the right of asylum in times of war.

In the late Middle Ages, the Augsburg yeshivah made an important contribution to the development of the pilpul method of study and analysis of the Talmud. The variant of the pilpul method evolved in Augsburg is referred to as the “Augsburg ḥillukim.” The talmudist Jacob Weil lived in Augsburg between 1412 and 1438. While some Hebrew pamphlets were printed in Augsburg by as early as 1514, a Hebrew press was established in 1532.

Organizing the Jewish community

An organized Jewish community was again established in Augsburg in 1803. Jewish bankers settled there by agreement with the municipality in an endeavor to redress the city’s fiscal deficit. In practice, the anti-Jewish restrictions in Augsburg were eliminated in 1806, with the abrogation of the city’s special status and its incorporation into Bavaria; however, the new Jewish civic status was not officially recognized until 1861. In 1871, Augsburg was the meeting place of a rabbinical assembly dealing with liturgical reform. The Jewish population increased from 56 in 1801 to 1,156 in 1900. It numbered 1,030 in 1933. In 1938, the magnificent synagogue dedicated in 1917 was burned down by the Nazis. In late 1941, after emigration and flight to other German cities, the last 170 Jews were herded into a ghetto, with 129 of them sent to Piaski in Poland in April 1942 and the rest mostly to the Riga ghetto and Theresienstadt. In the immediate postwar period, a camp was established in Augsburg to house displaced Jews. A few weeks after the liberation, services were resumed in the badly damaged synagogue by survivors of the Holocaust and Jewish soldiers of the U.S. Army, and the community was eventually reestablished. The synagogue was restored and rededicated in 1985. As a result of the immigration of Jews from the Former Soviet Union, the number of community members rose from 199 in 1989 to 1,619 in 2003.

The Synagogue

In 1861, the community received the government’s authorization to build a synagogue. The construction began in March 1864, and the official inauguration took place on April 7, 1865. Quickly, this building became too small, and in 1900 it was decided that a bigger synagogue had to be built. Its construction began in 1914, but the outbreak of the First World War significantly delayed the work that ended in 1917 due to a lack of workers and materials.

Designed by Fritz Landauer et D. Heinrich Lömpel, the synagogue is magnificently built in the late Jugendstil (Art Nouveau) style while fitting perfectly into the baroque style of the city. Above the roof, on both sides of the dome, sit two lions, a symbol of the tribe of Judah. The whole building is 27 meters long and 27 meters wide. The height is 27 meters to the lamppost on the dome. The cupola has a diameter of 16 meters. The shape of the windows with their stone filigree pattern and the shape of the cupola emphasize its oriental inspiration. Almost 800 places are available for men and women who are separated.

On the keystone of the door of the Hall of Columns, sculptor Walter Sebastian Resch engraved the date 1298 with a Star of David and the arms of the city to commemorate the city’s centuries-old relationship with the Jewish community. In the courtyard, a marble ornamental pond supported by animal sculptures is fed by a spring. A sentence in Hebrew on the basement mentions, “May all those who are thirsty come, here flows the spring”. The houses of the rabbi and the cantor, the administrative offices, and the school, as well as a small prayer room for the working days, are located in the two buildings overlooking the street.

After the inauguration of the new synagogue in 1917, the old synagogue in Wintergasse closed. The building was then used as headgear. It was completely destroyed during the Second World War.

During Kristallnacht, the synagogue was set on fire. Fortunately, the neighboring inhabitants, feared that the fire would spread to their homes and to kerosene tanks at a nearby petrol station, called firefighters who quickly extinguished the arson. The structure of the synagogue has therefore not suffered.

During the Second World War, the synagogue was used to store the sets of the municipal theater, while the Jewish school building was occupied by the Air Force Staff. The dome of the synagogue serves as an observation post for anti-aircraft defense artillery.

After 1945, the buildings are returned to the Jewish community. In 1964, the small synagogue is again inaugurated. Renovations started in 1975 and ended in 1985. On 1 September 1985, the synagogue was again inaugurated by an office in the presence of more than 120 members of the former community of Augsburg from around the world. At the same time, the Jewish Cultural Museum opened its doors in a part of the building. The latter was extensively renovated in 2005-2006.

The Jewish museum

At the same address, the Jewish Museum was founded in 1985. It documents the rich culture and history of the Jews in Augsburg and Swabia from the Middle Ages to the present.

The new permanent exhibition, installed in November 2006, presents this history as a story of migration and focuses on the relationship between the Jewish minority and the Christian majority. It also depicts the changes in religious practice in the course of time, showing Jewish history as an integral part of Augsburg and Swabian history. You will find a kosher coffee shop in the museum.

The Jewish cemetery

The cemetery was opened in 1867 and is presently still in use. Note however, that due to repeated vandalism, the cemetery is kept closed except for burials or announced visitors. The cemetery contains about 1500 graves.

Sources: Encyclopaedia Judaica ; Wikipedia ; Jewish Museum of Augsburg

A Jewish community is first mentioned in Leipzig at the end of the 12th century; and an organized community with a synagogue and a school existed from the second quarter of the 13th century.

Its central location attracted Jewish traders from all over Europe to the Trade Fair. The fair regulations of Leipzig of 1268 guaranteed protection to all merchants and moved the day of the market from Saturday to Friday for the benefit of the Jewish merchants.

A late development

A permanent Jewish settlement was founded in 1710. The number of “privileged” Jewish households allowed residence in Leipzig grew to seven by the middle of the 18th century. However, the Jewish community as an officially state-recognised organisation was established only in 1847 and only by then Jews were allowed to settle in Leipzig without any restrictions. After 1869, with the abolition of all anti-Jewish restrictions, the number of Jews increased greatly by immigration from Galicia and Poland.

Though most Jews were traveling merchants, in 1935 – less than a century after its establishment – the Jewish community in Leipzig consisted of 11,564 members, making it the sixth-largest Jewish community in Germany and the largest one in Saxony. The city’s mayor from 1930 to 1937, Carl Friedrich Goerdeler, although being national-conservative, was a noted opponent of the Nazi regime in Germany. He resigned in 1937 when, in his absence, his Nazi deputy ordered the destruction of the city’s statue of Felix Mendelssohn.

On Kristallnacht in 1938, 553 Jewish men were arrested, centres of Jewish communal life were destroyed, as well as one of the city’s most architecturally significant buildings, the 1855 Moorish Revival Leipzig synagogue. The deportations from Leipzig began on January 21, 1942, until February 13th 1945, when the last 220 Jews were deported to Theresienstadt. By 1945, there were only 15 Jews remaining in the city at which point 200 came back from Theresienstadt to form the Jewish community once again. In 1989, the community numbered 30 members, but as a result of the immigration from the former Soviet Union, it began to grow. In 2012, the Jewish community numbered 1300 members.

In 2010, two rabbis were ordained in Leipzig in a ceremony held in a small synagogue in the city. It marks the growth of the Jewish community, especially thanks to the arrival of Jews from Eastern Europe since the reunification.

The Brody synagogue

A small synagogue in 1897, which was enlarged into a two-story building in 1933; the prayer hall was on the first floor, and the second floor housed a library and study rooms. On Pogrom Night, November 1938, the windows of the synagogue were smashed and its interior was destroyed. Out of concern for the safety of neighboring homes, the synagogue was not set on fire.

In early 1939, the Nazis, wanting to convince the world of their tolerance, forced the Jewish community to refurbish the synagogue in time for the upcoming Leipzig fair. Shortly afterwards, they repossessed the building and used it as a soap factory. The building was returned to the Jewish community in 1945, after which it was once again used as a synagogue. In 1993, both the interior and exterior of the synagogue were restored.

Today, Leipzig has the most active Jewish community in Central Germany. As a matter of fact, the Brody synagogue holds the only daily Minyan in the region.

Cemeteries

In Leipzig there are two Jewish cemeteries. The new cemetery has been used since 1927. In April 1972, construction began for the renewal of the celebration hall, together with the refurbishment of the religious-ritual space. The old cemetery is located on Berliner Straße.

The Holocaust memorial

On the site of the Moorish synagogue stands today the Holocaust memorial. This powerful installation is made of 140 empty bronze chairs, representing the 14.000 Jews who once prayed there and outlining the floor plan of the destroyed synagogue.

The Jewish community today

A community center holds conferences and activities. In 2006, a mikveh was opened at the same address.

In 2010, two rabbis were ordained in Leipzig at a ceremony held in a small synagogue in the city. It marks the growth of the Jewish community, thanks in particular to the arrival of Jews from Eastern Europe since reunification. The community had 12,000 members before the war, only 30 after the fall of the Berlin Wall in 1989 and almost 1,300 in 2010.

Most of the Jewish sites in beautiful Tbilisi are concentrated in the old city, in the neighborhoods along the left bank of the Kura River. Starting from the Vakhtang Gogasali Square (Meidan Square), located near the traditional Persian baths, take the main street of the old town, Kote Afkhazi Street, which you will go up a hundred meters to see on your left the Great Synagogue of Tbilisi.

Built at the beginning of the twentieth century in the area of the old Armenian bazaar by worshipers from Akhaltsikhe, in southern Georgia, hence the synagogue name Akhaltsikhe sometimes used to designate, the great synagogue of Tbilisi is an imposing brick building of Moorish inspiration, with interior facades decorated with beautiful newly renovated gold and blue frescoes.

If you are in Tbilisi during Shabbat or during a Jewish holiday, be sure to attend the services of the Great Synagogue, conducted according to the Georgian Jewish rite and usually welcoming a large number of faithful. Make the most of your visit to the synagogue and grab a meal at David restaurant, adjacent to the latter and in which you can enjoy, in the strictest rules of kashrut, delicious Georgian dishes such as khinkali, a kind of big stuffed ravioli, or the katachpuri, a big bread loaf.

Close to the Great Synagogue, at 2/5 Jerusalem Street, is another kosher restaurant, the Jerusalem restaurant, opened by Georgian Jews who returned from Israel in the 2000s.

Going back to Kote Afhazi Street, which continues along Leselidze street, you will see at number 28 of this street the Tbilissi synagogue, the so-called Ashkenazi synagogue, located in a courtyard made up of a group of traditional houses, and indicated by a sign in Hebrew in the street. Originally built in the early twentieth century for the Ashkenazi Jewish community of Georgia, this synagogue, also named Beit Rachel, was rebuilt in 2009, the original building being heavily damaged in the aftermath of the 1991’s earthquake. Shabbat and feasts are regularly held in this synagogue, run by the Habad movement. If you are in Tbilisi during Shabbat, you can also spend dinner in this community: it is always a very welcoming experience. The small synagogue of Tbilisi also has a Beit Habad.

Walk up Kote Afkhazi Street until you reach the intersection with Anton Katalikosi Street, which you will take until number 3, where the Jewish Museum of Tbilisi is located. Named in honor of David Baazov, a Georgian rabbi who played a significant role in the development of the local Zionist movement, the Jewish Museum of Tbilisi was inaugurated in 1932, then closed in 1951, in a context marked by a surge of anti-Semitism. This was indeed the time of the struggle against “cosmopolitanism” and the so-called “white coats conspiracy”. Its doors were reopened in 1992, after independence, and it is now housed in a beautiful brick building built in the early twentieth century and previously used as a synagogue.

Of modest size, the Jewish Museum of Tbilisi houses a number of objects of daily life and religious Georgian Jews and offers a valuable panorama of this community to history often unknown. You can also admire the paintings of Shalom Koboshvili (1876-1941) and David Gvelesiani (1890-1949), two famous Georgian painters of Jewish faith. In addition, the David Baazov Museum regularly hosts temporary exhibitions, usually dedicated to the history of Jewish communities in Europe.

The National Museum of Georgia, located not far from Freedom Square on Shota Rustaveli Avenue, also has a substantial Jewish fund, which in recent years has been the subject of an admirable work of valorization. You can prepare your visit by consulting the website Jewish Cultural Heritage, which exhaustively lists all the particularly rich collection of Jewish history and art of the museum.

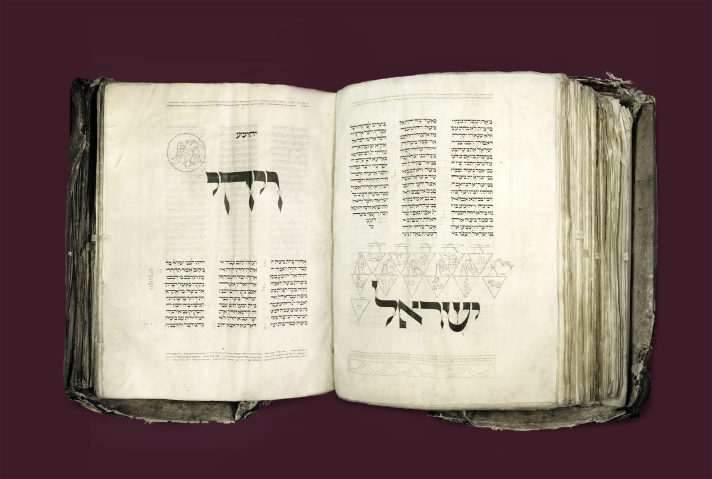

Finally, you can also admire at the Institute of Manuscripts of Georgia, located a little further north of the city near the Technical University subway station, a splendid Torah dating from the 10th century, discovered in the 1940s in the region of Svaneti, in the village of Lailashi.

You can finish your tour in Jewish Tbilisi by visiting Jewish cemeteries on the outskirts of the city. There are three. The one traditionally reserved for the Ashkenazi community is in the village of Navtlugi. The village of Ortchala is home to another Jewish cemetery. These two cemeteries are no longer active but are maintained by the community, which continues to bury its faithful at the cemetery of Dampalo, in the village of Varketili. As these three cemeteries are on the outskirts of Tbilisi, the taxi is still the easiest way to get there.

In recent years, and particularly since the pogrom of 7 October, Georgian cities, including Tbilisi, have seen a revival of local Jewish life, far removed from the numerous manifestations and acts of anti-Semitism present in many European cities.

Not far from Tbilisi, about 90 kilometers away, is the town of Gori, the birthplace of Joseph Stalin, to whom a museum is dedicated.

The marshroutka is the most economical way: departure every 20 minutes or so from Didube bus station in Tbilisi for about one hour and a half. You can otherwise take a taxi. At 25 Kasteli Street, on the first floor of the courtyard of a house, you can see the small and cozy Gori synagogue , built in the 1940s: at this address is also a mikveh and a traditional oven matsot. During our visit, the Jewish community of Gori, today reduced to about twenty people after more than 200 worshipers left the city following the 2008 Russian-Georgian conflict, was still meeting in the synagogue for shabbat. The Gori Cemetery, which has a Jewish square, is on the edge of town, about a 20-minute walk from the center. You can access it by going up, from the Stalin museum, to Sameba street.

Large city on the shores of the Black Sea and an important seaside resort, Batumi still has some Jewish sites. From Tbilisi, the easiest and most pleasant way is to go by train (about 5 hours, about fifteen dollars). Beautiful white building, the synagogue of Batumi is located at number 33 Vazha-Pshavela street, in the old town, which you will reach from the station along the waterfront.

It was built between 1900 and 1904 on the personal authorization of Tsar Nicholas II and according to the plans of the architect Simon Volkovich, who drew inspiration from the synagogues of Amsterdam and The Hague.

The Batumi synagogue was used by Ashkenazi Jews in the city until 1923. It was then used as a sports hall during the Soviet period, before being surrendered to the community in 1993 and reopened in 1998.

A dozen of a few minutes walk up the road to Vakhtang Gorgasali street, you will find at number 10 of the latter the Beit Chabad Batumi, particularly active in summer during the influx of Israeli tourists. At this address, you can eat kosher at Mendy’s, which offers Georgian and Israeli dishes in a very friendly atmosphere.

Since the pogrom of 7 October, Georgia, and particularly the city of Batumi, has been a welcoming place for Jews, bucking the trend in many European cities. This is evidenced by the growth of local Jewish life. Batumi has four synagogues and several kosher restaurants.

A very interesting encounter with Georgian Judaism is possible by visiting the village of Akhaltsikhe. Located on the road to Batumi, the second largest city in the country, Akhaltsikhe is accessible from Tbilisi either by minibus or taxi, about three hours drive. You can also take the train to Moliti station, then taxi to Akhaltsikhe.

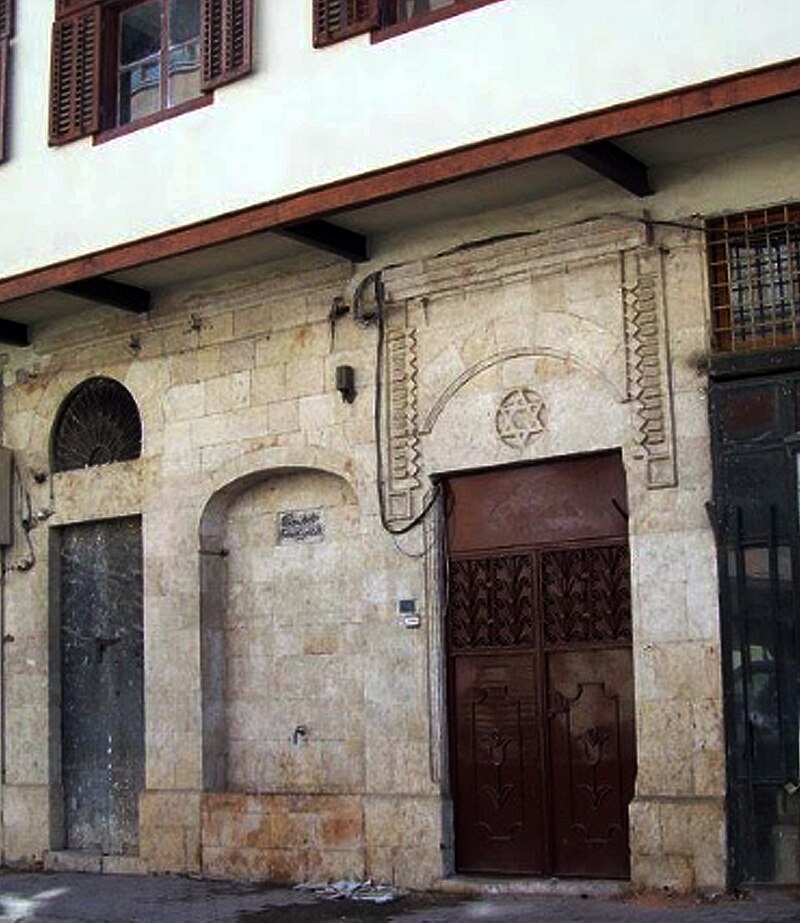

It is in the old district of Rabati, located in the city center under the fortress, that is the oldest synagogue of Georgia still partially in service.

Built in 1863, this Georgian rite synagogue was extensively renovated in 2012 and now features a beautiful interior of painted wood.

Partly used as a museum where the portraits of the generations of rabbis who have officiated, it is open for tourists in the summer, mainly Israelis, who come to visit the region.

In the same street, about twenty meters below, you will find the second synagogue of Akhaltsikhe, built at the beginning of the twentieth century and now abandoned, having served as a gym from the early 1970s on.

However, the building remains in a relatively good state of conservation. Located on a hill overlooking the ancient Jewish quarter, the imposing Jewish cemetery of Akhaltsikhe houses tombs, some dating back to the seventeenth century.

The inscriptions in Ladino that you will notice on some of them confirm that at least some of the Jews of the city had arrived from the Ottoman Empire and originally came from the Iberian Peninsula, which seems consistent with the proximity of Turkey, only a few kilometers away.

You will be able to finish your visit with the Akhaltsike Fortress Museum, where several paintings depicting the life of the Jewish community of Akhaltsikhe in the nineteenth century are displayed.

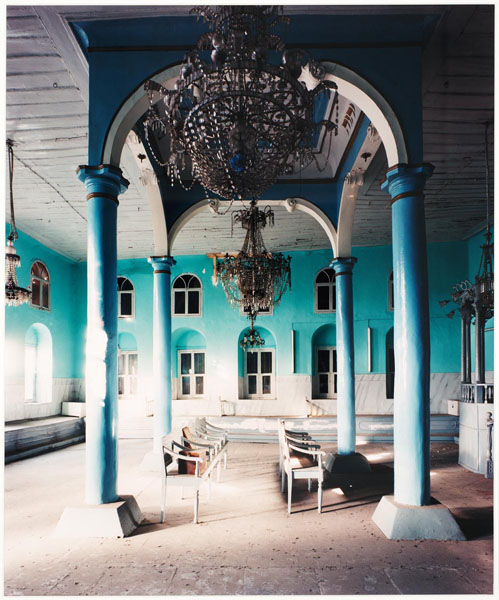

In the north of the country, the city of Oni, about 200 kilometers from Tbilisi, is home to a wonderful synagogue, in excellent condition, located on Baazovi Street. Built in the 1890s according to the plans of an architect from Poland and Jewish workers from Salonika, this beautiful Moorish-style building housed the third largest community in the country after Tbilisi and Kutaisi in the early twentieth century.

According to an ancient legend of Georgian Judaism, one of the stones of the Second Temple of Jerusalem, would have been scattered in the air after its destruction in 70, and would have landed in the Caucasus Mountains, in Oni. It was at the place where it crashed that the synagogue was built. At the beginning of the twentieth century, the rabbi of Oni was none other than the famous David Baazov. This is where his son Hertzel Baazov was born. The famous writer was executed for dissent in 1938.

Strongly damaged during the 1991 earthquake, the synagogue of Oni has since been the subject of a major restoration. It should be noted that while most of the Oni churches were destroyed during the Soviet period, the synagogue, thanks in particular to a strong mobilization of the inhabitants of Oni and the Jews of Tbilisi was totally spared. It is no longer used in its religious functions but can still be visited. If it is closed during your visit, inquire at the nearby Oni Museum.,

Oni also has nowadays a poorly maintained Jewish cemetery, located about 500 meters north of the synagogue, a little further up Baazovi Street.

The second largest city in the country of Georgia, Kutaisi is located just over 200 kilometers northwest of Tbilisi. The cheapest way to get there from the capital is the minibus (about 4 hours drive), and the most pleasant the train (about 5:30 of journey).

The Jewish community of Kutaisi was one of the largest in Georgia. It was located in a neighborhood on either side of Boris Gaponov Street.

The latter was the translator of the Georgian to the Hebrew Knight’s Panther-skin, an epic poem and central element of Georgian literature written in the twelfth century by Shota Rustaveli. It is in this street that are the three synagogues of Kutaisi. The largest of them, number 57-59, was built in the 1880s.

Adorned with impressive interior frescoes recently restored, the great Kutaisi synagogue still operates for Shabbat and feasts. The other two synagogues, number 8 and number 10, built in the 1860s, of smaller sizes, are now closed; however, you can visit them, especially if you come in summer.

The Jewish community of Erfurt first appears in the historical record in the late 11th century, with the earliest recorded building of the synagogue dating from then. For centuries Jews and Christians lived side by side in the centre of town. There is more detailed evidence from the 13th century. We learn from tax lists and deeds that Erfurt Jews worked in banking, and dealt not only with local towns and aristocrats, but had business relationships across the Holy Roman Empire.

Their residential neighbourhood was in the immediate city centre, in the quarter between the town hall, Krämerbrücke and Michaeliskirche. Here they lived in close proximity with Christian merchants and here stood their representative synagogue. Close by was a mikveh, a Jewish ritual bath. The cemetery was outside the residential area at Moritztor.

Eminent scholars lived and taught in Erfurt. Evidence for the developed intellectual life are 15 Hebrew manuscripts that belong today to the Berlin State Library.

The wave of Jewish persecutions, reached Erfurt in March 1349. During the pogrom on 21 March 1349 the whole Jewish community of Erfurt was destroyed and up to 900 people died. A merchant subsequently converted the Old Synagogue into a storehouse.

Erfurt welcoming Jews again

A short time later, probably from 1354, Jews became resident in Erfurt again. The Erfurt Council had a synagogue built behind the town hall between 1355 and 1357 for the new community. The Jews lived to a large extent in the same quarters, but now for the most part in rented accommodation in municipal “Jews houses”.

There were also in this second settlement some very wealthy and influential families who worked in overseas trade and finance. Numerous poorer Jews lived from pawn broking, trading and the manufacture of shofars. In the 15th century anti-Jewish sentiment was growing in Erfurt. In 1453 the municipal council revoked the protection of the Jews, and all Jews left the town around this time. Since the year 1454 Jews were no longer tolerated in Erfurt. The Jewish dwellings were sold, the synagogue was converted into an armoury and the cemetery was razed.

There was no established Jewish community in Erfurt between the expulsion by the council in 1453 and the Napoleonic Wars. When the Principality of Erfurt became a French imperial territory it was subject to the Napoleonic code, the French civil code of laws formulated in 1804, which permitted freedom of residence. David Salomon Unger was the first Jew to become a citizen of Erfurt in modern times. In the 19thcentury a community was re-established and grew rapidly.

Persecution and Shoah

In the night of the 9 to 10 November 1938 Erfurt’s Synagogue was ransacked by the SA and set on fire. The gymnasium of the school on Meyfartstraße served as collection point for approximately 200 men who were then taken to Buchenwald Concentration Camp. On 6 April 1939 all properties of the former synagogue community were appropriated by the city of Erfurt.

In 1932 there were 1,290 inhabitants with Jewish confession of faith in Erfurt. Following the transfer of power to the National Socialists the census in June 1933 only showed 831, in May 1939 only 263. A small group returned to Erfurt from Theresienstadt Concentration Camp.

In 1945, after the Shoah, only about 20 members of the re-established Jewish community headed by Max Cars had been part of the pre-war synagogue community, but their numbers were augmented by incomers from other regions, mostly from Eastern Europe. At the same time many were emigrating to Israel. On 31 August 1952 the New Synagogue was inaugurated on the site of the destroyed Great Synagogue. This is where community life and worship take place today: Since 1990 the Erfurt community has enjoyed an influx of members, mostly from the states of the former Soviet Union. Today the Jewish Community of Thuringia has around 800 members.

Old Synagogue

The Old Synagogue, with parts dating from the 11th century, is the oldest synagogue in Central Europe that has been preserved up to its roof. In 2009 a museum was created here, in which medieval reminders of the Erfurt Jewish community can be viewed.

The exhibition in the Old Synagogue shows the history of the first Jewish community in Erfurt. In the courtyard gravestones of the destroyed medieval cemetery can be seen. The building history of the synagogue is the subject on the ground floor. The cellar houses the treasure found near the synagogue, which a Jew buried during the pogrom of 1349. The Erfurt Hebrew Manuscripts are addressed on the upper floor.

Great Synagogue

Designed by Frankfurt architect Siegfried Kusnitzky, it was inaugurated on 4 September 1884. The Great Synagogue could accommodate 500 people, was richly decorated inside, adorned with coloured paintings, and had an organ. It was the centre of the community for 45 years – until its destruction in 1938.

The New Synagogue was built in 1951/52 on the site of the Great Synagogue and was inaugurated on 31 August 1952 and is today the centre of a lively community life.

Small Synagogue

On 10 July 1840 the Jewish community consecrated the Small Synagogue. It was used as a house of worship for only 44 years, until 1884, since the community was growing fast in the 19th century. The community built the Great Synagogue and sold the Small Synagogue to a merchant. He used the house as a storage facility and production building. In 1918 the municipality installed apartments. Interest in the Jewish heritage grew in the 1980s. The town had the building history of the synagogue researched and the building restored. Building researchers found the mikveh as well as the Torah shrine and the women’s balcony. So the prayer hall presents itself today in the almost original condition. The Small Synagogue serves today as a meeting centre and shows an exhibition on Jewish life in Erfurt in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Medieval Jewish Cemetery

At Moritztor, today’s Große Ackerhofsgasse, the cemetery for Erfurt’s Jewish community was located in the Middle Ages. It is probable that the site was used for burials ever since the beginnings of the community. The oldest gravestones still preserved today are from the 13th century.

In 1453 the cemetery was razed and in its place a municipal barn and later the large granary were erected. The gravestones were used as building material all over town, which is why until today they are occasionally rediscovered in buildings or in the pavement.

In remembrance of the cemetery to start with a memorial stone was erected in 1996. Since the year 2000 there were discussions to make the cemetery visible again, and the realisation started in 2007.

New Jewish Cemetery

When a community re-established itself in Erfurt in the 19th century, as the community rapidly grew the medieval cemetery became too small for further burials. Since the opening of the New Jewish Cemetery in 1878 members of the Jewish community are buried there. It is as well the only one actively used in Thuringia.

Mikveh

Documentary evidence on the mikveh goes back to the middle of the 13thcentury. It shows that the Jewish community had to pay charges for the ritual bath and for the land, initially to the bishop, later to the city of Erfurt. From the medieval tax lists we learn that the environs of the mikveh were densely populated.

Erfurt Hebrew Manuscripts

The Erfurt Hebrew Manuscripts are evidence of the importance of the medieval Jewish community. Fifteen manuscripts from the 12th to the 14th century have been preserved, more than from any other community. Apart from four Torah scrolls there are, amongst other things, four Hebrew Bibles bequeathed as well as a machzor.

The manuscripts probably came into the hands of the Erfurt Council during the pogrom. It sold some books shortly afterwards, others stayed in the possession of the city until the 17th century. How they finally ended up in the library of the Evangelical Ministry in the Augustinian Monastery is unclear. The Ministry sold them to the Royal Library in Berlin, today’s Berlin State Library, in 1880.

In a cooperation project between the network “Jewish Life Erfurt”, the Berlin State Library – Prussian Cultural Heritage, and the Free University of Berlin, chair of Jewish studies, the specialist Annett Martini is researching the Erfurt Hebrew Manuscripts. The results are integrated into the permanent exhibition in the Old Synagogue.

Erfurt Treasure

In the cellar of the Old Synagogue, the so-called Erfurt Treasure is exhibited, which was most likely buried during the pogrom of 1349 – a unique find in size and composition. It was discovered in 1998, shortly before archaeological investigations on the site of Michaelisstraße 43 – not far from the Old Synagogue – were completed. It had been hidden underneath the wall of a cellar entrance.

The treasure has a total weight of nearly 28 kilogrammes. With around 24 kilogrammes, 3,141 silver coins and 14 silver ingots of different sizes and weight form the biggest part of it. Moreover, the hoard contained over seven hundred individual items of gothic goldsmith’s art, some highly accomplished.

Among them is an ensemble of silver tableware, consisting of a set of eight beakers, one ewer, one drinking vessel as well as a double cup. Among the pieces of jewellery, eight brooches of different sizes and form, partly with abundant ornamentation of precious stones, stand out as well as eight gold and silver rings. Yet, smaller objects such as parts of belts and garment trimmings numerically form the biggest part of the goldsmith’s works.

The treasure’s most outstanding object is a Jewish wedding ring from the second quarter of the 14thcentury. Most captivating is the craftsmanship of its Gothic miniature architecture, made of pure gold.

That, accordingly, is what makes the Erfurt Treasure so unique and why it has already been exhibited in New York, London and Paris before being put on permanent display in the Old Synagogue since 2009.

Jewish community today

The Jewish Community of Thuringia has, next to its synagogue, a cultural and education centre. It hosts Via Schalom, the Jewish Cultural Initiative in Thuringia, founded in 2000, which promotes a better understanding between Jews and non-Jews via a number of cultural events; Radio Schalom, the community radio station; and a coffee shop.

In September 2023, a group of buildings bearing witness to Erfurt’s medieval Jewish past was added to UNESCO’s World Heritage List, becoming the 52nd site in Germany to receive this distinction.

Source: Jewish Past and Present in Erfurt

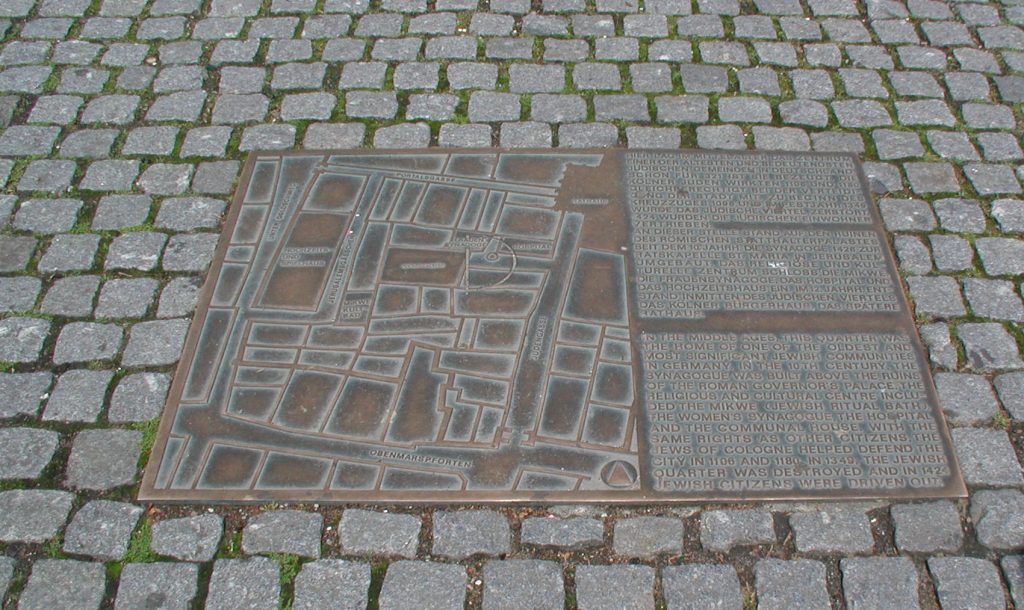

The history of the Jews in Cologne is documented from the year 321 AD, almost as long as the history of Cologne. Over its history, the Jewish community of Cologne has suffered persecutions, many expulsions, massacres and destruction. The community numbered about 19,500 people before its dispersal, murders and destruction in the 1930s by the Nazis before and during World War II. The community has re-established itself and now numbers about 4,500 members. Because of its historical continuity, today’s Jewish synagogue calls itself the “oldest Jewish congregation north of the Alps”.

2000 years of Jewish history

Cologne was founded and established in the 1st century AD and it is reasonable to assume that the spread of Christianity in any Roman province was preceded and accompanied by the existence there of Jews. The presence of Christians in Cologne in the 2nd century would therefore argue for the settlement of Jews in the city at that early date. Judaism was recognized as a religio licita (permitted religion). In 321, a decree of Emperor Constantine the Great of 321, permits Jews to be appointed to the curia. In another document, from 341, it is recorded that the synagogue was provided with the emperor’s privilege. These decrees of Constantine remained for some centuries the only accounts of the existence of a Jewish community in Cologne.

During the Middle Ages, Cologne flourished as one of the most important trade routes between east and west Europe. The first documentary reference to the Jews in Cologne in the Middle Ages was in 1426 when a report mentions a 414 year old synagogue turned into a church. The number of Jews in the community during the last quarter of the 11th century was not less than 600. The markets of Cologne had attracted many Jewish visitors who had partly stayed. Italian Jews are mentioned in the stories about the Crusaders in Cologne.

Persecutions and pogroms

During the Middle Ages, the Jewish community had been settled in a quarter near the Rathaus. Still now the name “Judengasse” testifies its existence. During the First Crusade in 1096 there were several pogroms. On 27 May 1096, hundreds of Jews were killed in Mainz during the Rhineland massacres. A similar thing happened in July of the same year in Cologne. The Jews were forcibly baptized. The permission of Emperor Henry IV to let the Jews who had been forcibly baptized go back to their faith was not ratified by Antipope Clement III. During the Second Crusade, it seems that the Jews of Cologne were somehow spared.

An early pogrom against had taken place after the Battle of Worringen on 8 June 1288. For days afterwards a persecution of Jews swept through the surroundings of Cologne. In 1300, a wall was built around the Jewish Quarter, presumably paid for by the Jewish Community itself.

In the course of St. Bartholomew’s Night in 1349 the Jewish quarter near the town-hall (Rathaus) was attacked, after which killing, plundering of Jewish properties, and arson followed. In its escape from the riot one family buried its belongings and merchandise. The hoard of coins was discovered during excavations in 1954 and is now exhibited in the Kölnisches Stadtmuseum .

The Jews of Köln seemed, according to documents, to have returned only in 1369, although a small community was documented beforehand.

There is proof that by 1372 a small Jewish community had again sprung up in Cologne. At the request of Archbishop Frederick, the Jews were admitted to the town and obtained a temporary protection privilege for ten years. To this, however, the Council attached some conditions. For the privilege of admission there was a tax . After further extensions of the right of residence the Council proclaimed in 1404 a more restrictive Judenordnung. It ordained that the Jews had to be recognizable by wearing a pointed Jewish hat and banned any displays of luxury on their part. In 1423 the Cologne Council decided not to extend the temporary right of residence, which expired on October 1424.

Spitirual and intellectual development

In 1424, Jews were banned from the town “for eternity”. Following the medieval pogroms and expulsion of 1424, many Jews of Cologne emigrated to central or northern European countries like Poland and Lithuania. The offspring of these emigrants returned to Cologne at the beginning of the 19th century and lived mainly in the area of Thieboldsgasse on the southeast side of Neumarkt. Only a few Jews remained near Cologne and settled predominantly on the eastern bank of the Rhine (Deutz, Mühlheim, Zündorf). Later new communities developed, which grew over the years. The first community in Deutz lived in the area of the present Minden Street (“Mindener Straße”).

After the destruction of the community during Second World War, the medieval foundations were discovered, among them a synagogue and the monumental Cologne mikveh (ritual bath). The archeological survey was conducted after the war by Otto Doppelfeld from 1953 to 1956. On the basis of the awareness of history the area has not been reconstructed after the war and has remained as a square in front of the historical Rathaus. Today, the Jewish quarter is part of the Archeological zone of Cologne.

In Cologne there was one of the largest Jewish library of Middle Ages. After the massacre of the Jews in York, England in 1190, a number of Hebrew books from there were brought to and sold in Cologne. There are a number of remarkable manuscripts and illuminations prepared by and for Jews of Cologne during the 12th to the 15th centuries and now kept in various libraries and museums throughout the world. Cologne was as well a center of Jewish learning, and the “wise of Cologne” are frequently mentioned in rabbinical literature. A characteristic of the Talmudic authorities of that city was their liberality. Many liturgical poems still in the Ashkenazic ritual were composed by poets of Cologne.

The Jewish cemetery of Cologne is mentioned in 1906 and was of a size of about 30000 m2. The eldest tombstone found to this day is from 1152.

Right-Rhenish Deutz and its Jewish quarter

After the expulsion, the few Jews who remained in the city, began to re-establish a community in right-Rhenish Deutz, today part of Cologne. In 1634, there were 17 Jews in Deutz, in 1659 there were 24 houses inhabited by Jews and in 1764 the community consisted of 19 people. Towards the end of the 18th century the community still consisted of 19 people. The community was located in a small Jewish “quarter” in the area of Mindener and Hallenstraße. A synagogue, first mentioned in 1426, was damaged by the immense ice drift of the Rhine in 1784. The mikveh associated with the synagogue probably still exists under the embankment of the Brückenrampe (Deutzer Bridge). This first synagogue was then replaced by a new small building on the west end of “Freiheit”, the today’s street “Deutzer Freiheit” (1786–1914).

The history of the Jewish communities outside the city center is revealed above all through the remains of the Jewish cemeteries. There are right-Rhenish Jewish cemetery in Mülheim, in Zündorf , and one in Deutz. The latter was given to the Jews of Deutz by Archbishop Joseph Clemens of Bavaria in 1695 as a rented land. The first burials in the Jewish cemetery of Deutz took place in 1699. When in 1798 the Jews were again permitted to settle within the old city walls of Cologne, the cemetery was also used by this community until 1918.

Synagogues in Cologne

Due to the growth of the community and the disrepair of the prayer hall in the former Monastery of St. Clarissa, the Oppenheim family donated a new synagogue building at Glockengasse 7. The number of members of the community was now about of 1,000 adults. While in Medieval times the “quarter” had been built close to the synagogue in Cologne “Judengasse”, by now the Jews lived in a decentralized area among the rest of the population. Many lived in the new periphery quarters near the city walls.

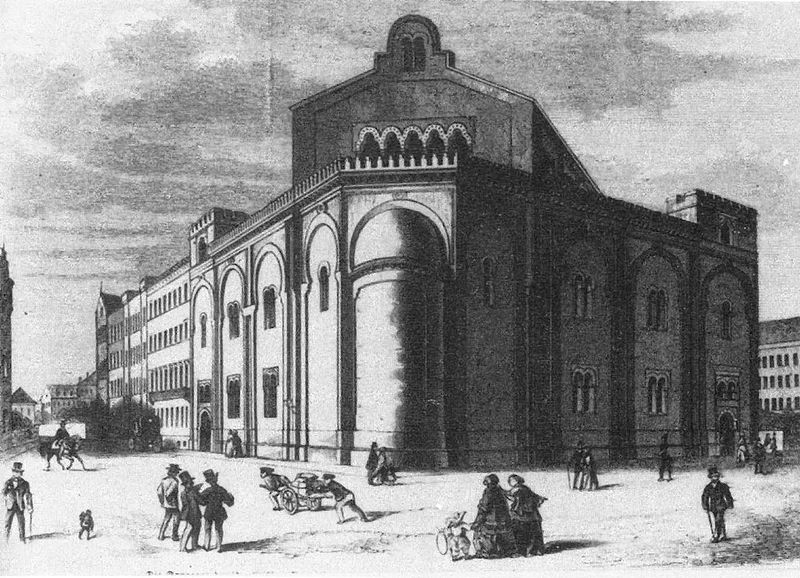

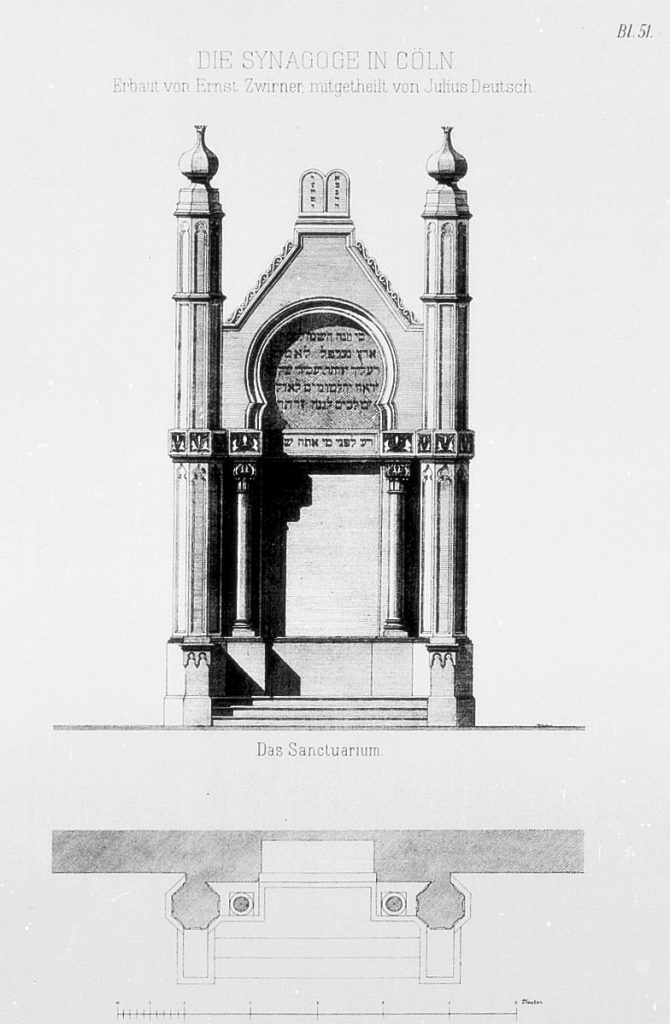

The project was won by Ernst Friedrich Zwirner, leading architect of the Cathedral of Cologne, who designed a building in Moorish style. The new synagogue was inaugurated after four years of construction in August 1861. The inner and outside design was to remind the bloom of Jewish culture during 11th-century Moorish Spain. The new synagogue had a façade of light sandstone with red horizontal stripes as well as oriental minaret and a cupola covered with copper plates. The ornaments in the inside were inspired by the Alhambra of Granada.

The new synagogue, which was valued positively by Cologne people, had seats for 226 men and 140 women. While set on fire in November 1938, the rolls of the Torah of 1902 could be saved, thanks to the Cologne priest Gustav Meinertz. After the war they were placed in a glass cabinet in Roonstrasse Synagogue. After a restoration, carried out in Jerusalem in 2007, they are now used again in the liturgies in Roonstrasse Synagogue, rebuilt after the war.

Built between 1895 and 1899, the Roonstrasse Synagogue was also destroyed during the Cristal night. It was rebuilt in 1959 and hosts today a community center, a kosher restaurant and a permanent exhibition about Cologne’s Jewish past.

The modern times

The head office of the Zionist Organization for Germany was based in Richmodstraße near Neumarkt square, Cologne, and was founded by lawyer Max Bodenheimer together with merchant David Wolffsohn. Bodeheimer was president until 1910 and worked for Zionism with Theodor Herzl. The “Kölner Thesen” developed under Bodenheimer for Zionism were — with few adjustments — adopted as the “Basel Program” by the first Zionist Congress.

About 40% of the Jews of Cologne had emigrated by 1939. In May 1941, The Gestapo started to concentrate all Jewish from Cologne in so-called Jewish houses. From there they were transferred to the barracks in Fort V in Müngersdorf. On 21 October 1941 the first transport left Cologne for Łódź, the last one was sent to Theresienstadt on 1 October 1944. Immediately before the transport the fair hall in Cologne-Deutz was used as a detention camp. The transports left from the underground part of the Köln Messe/Deutz Station. The deported people went to Łódź, Theresienstadt, Riga, Lublin and other ghettos and camps in the east which were only transit points: from here they went to extermination camps. When the U.S. troops liberated Cologne on 6 March 1945, between 30 and 40 Jewish men who had survived in hiding were found. More than 11,000 Jews from Cologne were murdered during the Holocaust.

On the site of the Archeological zone of Cologne, a Jewish Museum is under construction since 2010. It will be about 7000 m2 and will explore 2000 years of Jewish presence in Cologne.

A small synagogue was built in 1949. The Jewish community underwent a small renaissance, and as the number of worshippers increased, a synagogue was built ten years later on Roonstrasse, on the site where the large synagogue was burnt down during the Shoah. The project was supported by the German Chancellor at the time, Konrad Adenauer, himself a former mayor of Cologne who had been dismissed by the Nazis. Representatives of the political, religious and cultural authorities attended the inauguration.

In 2020, a city streetcar was decorated with texts and symbols announcing the 2021 celebrations marking 1700 years of German Jewish presence. With the words “Schalomschen Koln!” emblazoned on the vehicle.

In 2025, Cologne’s Jewish community numbered 5,000.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

Located in Podolia, equidistant from Kiev and Odessa, Vinnytsa is a city of cobbled streets, elegant avenues and numerous gardens, still very marked by its Polish past.

Its foundation dates back to the 14th century, when Podolia entered the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Integrated into the Republic of Poland-Lithuania at the end of the 16th century, it was then the capital of the province of Braslav – fundamental in the history of European Hasidism – and a major commercial, artistic and cultural center.

In 1793, following the second partition of the Republic of Poland, Vinnitsa was integrated into the Russian Empire and became the administrative capital of the region of Podolia, then bordering Poland. This proximity explains the very MittelEuropa atmosphere that you will feel in the city, even though Vinnytsia will remain under the authority of the Czars and then the Soviets until 1991. To get to Vinnytsia from Kiev or Odessa if you are not already in Podolia, the simplest and most comfortable is the train: allow around 4 hours and around ten euros, several departures per day.

Development of Jewish culture

The first traces of Jewish presence in Vinnytsa date back to the 16th century. The Jewish population of the city, massacred for the first time in 1698 during the capture of Vinnytsa by Bogdan Khmelnistky, then in 1750 during the uprising of the Haidamaks, grew rapidly after this wave of pogrom. It represented 12,000 people (or about 36% of the population) at the end of the 19th century, when the city had about twenty synagogues. If religious life comes to a halt with the start of the Soviet period from the 1920s – when nearly half of the city’s population is Jewish – cultural life continues around Yevseksia and several Yiddish publications. until the beginning of the 1930s.

The majority of the Jews of Vinnytsa, occupied from June 1941 by the Nazi forces, will be executed, as evidenced by the infamous photograph entitled The last Jew of Vynnitsa, taken by an SS during the final mass massacre of the city’s Jews in April 1942. This document will then be used during the Nuremberg trials as evidence. A small Jewish community, numbering around 1,000 people, survives in Vinnytsia today.

Promenade along the landmarks

Your walk through Jewish Vinnytsa begins as soon as you arrive, as in front of the train station, at the corner of Batozka and Kotsybunsko’ho streets, there is a large building in a beautiful red color dating from the end of the 19th century. It was previously home to the manufacture of Baruch Moisevich Lvovich , one of the city’s wealthiest entrepreneurs. His villa , neoclassical in style and in excellent condition, is located a little further in the city center, at 15 Petlioura Street (formerly Chkalova Street).

After being seized by the Petlioura government when Vinnytsa was briefly capital of independent Ukraine, it was transformed by the Soviets into a radio house in 1932. To head towards the city center, take Kotsybunsko’ho street to the river Bug, which you will cross to find yourself at the beginning from the main artery of the city, Soborna Street. At number 62 you will see the main synagogue in the city, still in operation.

A beautiful three-storey building, this synagogue was built at the end of the 19th century with funding from the entrepreneur Livchitz, who gave it its name. Closed by the Soviet authorities in 1929 and transformed into an arts club, it served as a theater for the Nazi occupiers during World War II, then as a philharmonic hall during the Soviet period. It was returned to the Jewish community in 1992, and now serves as the city’s main place of Jewish religious activity.

Visit of the mythical Savoy Hotel

Adjoining the synagogue, you will see the Brosky building, named after its original owner. This building is one of the city’s most marked architectural singularities. Opposite the synagogue, at number 69 Soborna Street, admire the facade of the beautiful Savoy Hotel, whose construction, commissioned in 1912 by Berich Markovich Lekhtman, was entrusted to the city’s most famous architect, Grigory Grigorievich Artinov. Still in operation and ideally located, the Savoy Hotel can serve as your accommodation if you decide to spend the night in Vinnytsia or Podolia.

You will arrive just after the Savoy Hotel at the crossroads of Soborna and Artinova streets, which you will take to enter Ierusalimka, the historic Jewish district of Vinnytsia. This well-preserved district was used as the backdrop for Jewish Happiness, a 1925 film directed by Alexei Granovski, with a screenplay by Isaac Babel. Take Hrycheskovo Street to your left, where at number 8 is the other working Vinnytsia synagogue , which also serves as the official seat of the city’s community as well as Beit Chabad. It is here that alternating with the synagogue on Soborna Street, Jewish holidays are held.

Synagogues listed as historical monuments

Continue along Hrycheskovo Street, pass Simon Petliura Street (where B.M. Lvovich’s home is located) to Chervonokhrestivs’ka Street, where you will see the Raikher Synagogue building at number 11.

Funded by Dr Raikher and designed by Vinnytsia’s main architect, Artinov, this neo-Gothic brick synagogue was transformed into a sports hall in the late 1920s, although a church service continued there until early 1900s. the Second World War. The building is now classified as historical monuments. Walk down the street until you find yourself back in Soborna Street.

Nearby, on Alexandra Solovieva Street, you can stop for a coffee or hot chocolate in the old tea, coffee and spice shop that belonged to the Fliegentyb family at the start of the 20th century. As his roasting business flourished and he soon opened branches in Kiev, Moscow and St. Petersburg, Moishe Fliegentyb had to change his name and adopt a less prominent surname, Matvee Zavarkine, to gain access to the imperial court. This shop, which is still open today, has been partially transformed into a museum, in which it is very pleasant to have a drink.

Holocaust memorial

You will arrive in Monastirska Street, where the house in which the famous Soviet avant-garde painter Nathan Altman was born is located. The artist left Vinnytsia for the Odessa School of Fine Arts in 1902, before settling in Paris and then returning in the 1930s to the Soviet Union. The painter immortalized the alleys of Ierusalimka in several of his paintings, among which The Jewish funeral, representation of the death of his grandfather, or in a collection of drawings, Vinnytsia in caricatures.

At the bottom of Kropivnitskovo Street, at the corner with Kniaziv Koriatovychiv Street, is a monument in honor of the poet Efim Aptekman , one of the founders of the “Futurist Marxist” movement. This monument also serves as a memorial to the Jewish victims of the Holocaust in Vinnytsia , the ghetto established during World War II located in this area. The main monument in honor of the victims of the Holocaust in Vinnytsia is located at the place where several thousand Jews of Vinnytsia were exterminated in September 1941. The memorial, made up of two monuments, one for adults and the other for children, is located on the outskirts of town, at Maksimovicha Street. To get there, take a taxi, the place being on the edge of the city.

You can end your day in Vinnytsia with a dinner at the Lvovskaya Cukernaya restaurant , very pleasantly located at the edge of the park and offering a delightfully old-fashioned atmosphere with a wide choice of Polish and Ukrainian dishes and pastries.

The terrifying war against Ukraine changes, of course, the function of these pages devoted to the Jewish cultural heritage of that country. Many of the places mentioned were razed to the ground by bombs. While these pages are not intended in the present time for tourism, they may be useful to researchers and students as historical references. References to so many painful histories during the pogroms and the Shoah, but also to the glorious history of Ukrainian Judaism, in its cultural, religious and Zionist dimensions. Wishing the Ukrainian people a speedy end to these atrocities of which they are victims.

Located at the junction of the Ingul and the Boug rivers, Nikolaev has a lesser known Jewish history than its 200 kilometers neighbour Odessa. However, it is a city with an important Jewish past: the lubavitch rabbi Menachen Mendel Schneerson was born there and Isaac Babel spent in Nikolaev some of his childhood years.

To get there, the simplest and cheapest is to take the marshroutka from Odessa’s Privoz bus station. During the day, there is one shuttle every 15 minutes or so. Once in Nikolaev, you can get down at the Tsentralnaya street (old Sovietskaya street), which is the only pedestrian street in Nikolaev, and located not far from the synagogues. From Odessa, you can as well take a taxi to Nikolaev, it will cost you about 60 Euros.

A community composed of Galician Jews

The first traces of a Jewish presence in Nikolaev date to the city’s foundation, in 1789. The city was back then mostly made of Jews from Galicia who came to build the Russian port. They rapidly grew strong enough to build their first synagogue in 1819, now known as the ancient synagogue, the building still stands.

In 1829, using the argument of military presence in Nikolaev, the Russian Empire forbade the Jews to live in the city. However, the city council, aware of the Jewish community economical importance disputed the Empire’s edict, which was nonetheless carried out in 1834. It will finally be under Alexander the Second reign (1855-1881) that Nikolaev will be integrated into the Residence zone and that the Jews will have the full right to inhabit it.

Place of birth of Rabbi Schneerson

According to the 1897’s census, the Jewish community of Nikolaev counts 22,000 people, 20% of the city’s population. The city had two synagogues, 15 prayer houses, and 15 schools. It is at this period was Menachem Mendel Schneerson, the famous Habad movement rabbi, was born. He will die in 1994 in Brooklyn. Also, in those years, Isaac Babel was a young boy in Nikolaev, before coming back to Odessa.

You can start your visit from Tsentralnaya street, toward Mala Morskaya, and until Velika Morskaya street. On the right, at number 71, you’ll find the building of the Landau Pharmacy, active in the 1870s, and which was one the the biggest in the city.

Taking the street in the other direction, you’ll cross Schneerson street (old Karl Liebknecht street): at number 15 you’ll find the only active synagogue of Nikolaev ran by the Habad movement. There is a mikvah as well. The Jewish community, around 2000 people, gathers here.

The Jewish Quarter

The adjacent building is the first synagogue of the city, which was built in 1822, and that was sometimes called the cobblers’ synagogue -the Jewish craftsmen were in majority shoemakers for the sailors of the city.

Although it hasn’t been in use since 1935, the building is in relatively good condition. Indeed, in 1935, the Soviet authority closed the synagogue and gave the building to various labor or cultural institutions. This sudden change of function explains why you will find soviet frescoes on the building’s facade.

Isaac Babel’s studies

At the corner of Velika Morskaya and Artilleriskaya, you’ll find at number 19 the old business school of Nikolaev. This building, mainly funded by Jewish tradespeople of the city, and therefore not affected by the quotas on Jewish students, was the school of Isaac Babel. A commemorative plaque outside the building is to be found.

On Spasskaya street, a parallel to Velika Morskaya, you can admire beautiful houses that once belonged to the Jewish nobility of the city and which are still in perfect condition. At number 18, you’ll find the Meshyres family house, and, at number 20, the Erlikh House. At number 33, you’ll find the Forshteter house.

Monument honoring the Lubavitch rabbi

Going back to Tsentralnaya street, and go toward Moskovskaya street. At the corner with Potemkinskaya street, at number 67, you’ll find the building that once housed one of the city’s heder.

Built in the 1820 in a mauresque style, the house was a pharmacy before becoming a study place. The facade is still intact. Walking back to Moskovskaya street, you’ll see at number 69 the monument to rabbi Schneerson, erected in 2011 at the location of the house where the rabbi was born in 1902.

Holocaust memorial