The East was home to both the city’s underprivileged social classes, victims of gentrification in other districts, and refugees from the continental conflicts of the 20th century: Armenians, Greeks and Jews. Between the 3rd, 11th and 19th centuries, the garment and shoe manufacturing industries developed, where many of these migrants were employed.

Before the war, Paris had 50,000 Jews from Eastern Europe, who constituted the vast majority of Parisian Jews until the 1970s. In the 1930s, most of them lived in different districts: the Marais, Belleville, La Roquette, Clignancourt and Saint-Gervais. These groupings were sometimes linked to their country of origin, religious practices and even political commitments.

In the 11th arrondissement neighbourhood of La Roquette, Jews from the Ottoman Empire, mainly from the regions of present-day Turkey, Greece and Bulgaria, settled at the beginning of the 20th century.

They settled for the most part between Place Voltaire, Rue Sedaine, Rue Popincourt and Rue de la Roquette. They worked mainly in textiles and lingerie and met regularly in cafés, including the famous Bosphore, and in small clubs.

The construction of the Don Isaac Abravanel synagogue was decided upon in order to promote the revival of Levantine Judaism, following the numerous deportations of the Shoah and the arrival of Jews from North Africa. A hundred metres away, on the Léon Blum square, stands a statue honouring the memory of the head of government who introduced paid holidays.

Built by the architect Alexandre Persitz, it was inaugurated in 1962 by Chief Rabbi Jacob Kaplan who saw in it the symbol of the link between tradition and modernity. Traits of this modernity are the facade divided into two levels, a courtyard preceding the synagogue behind the entrance gate, the sobriety of the religious motifs and the inscription in French of the 10 commandments.

During the Second World War, many Jews from the working-class neighbourhoods of the East joined the Resistance, including members of the Manouchian group and young people like Henri Krasucki.

A large fresco honours the courage of theManouchian group who led daring attacks against the Nazis and their Vichy servants before being captured and executed.

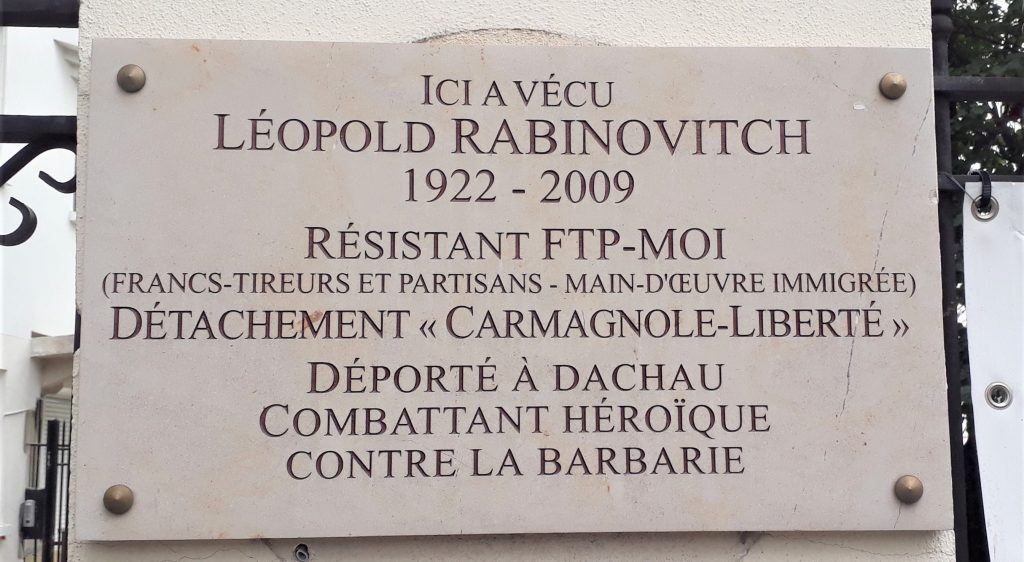

Numerous commemorative plaques recall the involvement of these Jews in the Resistance and the large number of Jewish children deported to this part of the city on the school grounds.

Among the places honouring these Resistance fighters are the statue of Marcel Rajman (member of the Manouchian group), Hélène Jakubowicz street and the plaque in memory of Léopold Rabinovitch .

Many Armenians from these neighbourhoods, whose families had experienced genocide a generation earlier, showed solidarity with the Jews, helping them to hide.

Another emblematic district of the working class environment is Belleville where many Jews live and work, diversifying by participating in all sorts of trades: grocery shops, cafés, newspapers… The Polish Jewish workers forming a large number of the workers in the fabric, leather and shoe industries, live in great precariousness.

After the war, because of the large number of deaths during the Shoah and the change in the area of migration, the Belleville neighbourhood gradually became an emblematic Tunisian Jewish neighbourhood, mainly from the working classes, like those from Eastern Europe before them. Many Tunisian restaurants, such as René & Gabin, grocery shops and places of worship opened in the 1960s.

Among the remaining synagogues in Belleville, the Pali Kao synagogue , inaugurated in 1930, should be noted first. Designed by the architects Germain Debré and Lucien Hesse, it represents the first modernist Jewish place of worship.

Modern because it favours the functional aspect allowing the place to serve both as a place of worship and culture. But also the few ancient motifs and the discretion of its façade. Both Ashkenazi and Sephardic rites are now performed in this place. Also in the neighbourhood, two synagogues dating from the 1960s, Or Hahaïm of Constantinian rite and Michkenot Yaacov of Tunisian rite.

Since 2000, following the sharp rise in anti-Semitic acts, many Jews have left the working-class neighbourhoods of eastern Paris to find refuge in the 11th, 20th and surrounding areas of Saint-Mandé and Vincennes. There are small oratories near the Boulevard Voltaire between the place of the same name and the place de la Nation. But also cashers and restaurants.

Since the turn of the century, the growing success of the massortis and liberal communities in Paris, particularly in the East, should be noted. With the Dor Vador , JEM East and JEM Surmelin synagogues in the Gambetta district. Neighbourhood near the Père Lachaise Cemetery, where many great figures of French history are buried.

Near the allée Chantal Akerman , in the 20th arrondissement of Paris, one of the greatest filmmakers of all time lived from the age of 18. “My daughter from Ménilmontant”, as she is nicknamed by her mother Natalia in the book “A Family in Brussels”, is a dialogue of memories, stories and silences. Brussels and Paris devoted a major exhibition to her in 2024-5, and her films are still regularly shown in cinemas around the world.

Like Albert Cohen, she is the author of masterpieces in many different genres. The only difference, perhaps, is that she didn’t need to make “The Film of My Mother” when it was too late, since Natalia Akerman has been in the limelight right from the start of her daughter’s work.

An Auschwitz survivor, Natalia doesn’t talk about it, torn between the imminent need to hold on and rebuild and the Jewish resilience that consists of promising a better dawn for the next generation. All the while, she passes on her strength and dignity to her daughters Chantal and Sylviane.

From her father Jacob, they inherit humour, hard work and a willingness to dance through life and out of trouble. Jacob Akerman is a shopkeeper, owning a clothing factory in the Triangle district and a shop in the Toison d’Or gallery.

As for Brussels, it shares with the two young women born in the aftermath of the war, its bon vivant Belgian spirit, with its cartoon characters, glasses and stories all rounded off to facilitate boats overflowing with pleasure, inspiring in its own way so many stories with cheerfully spilled beers.

Chantal’s Polish maternal great-grandfather was on his way to the United States, trying to reach the port of Antwerp to embark. But like so many Jews, he realised just how happy life could be for a Jew in Belgium.

Chantal Akerman was born in Brussels in 1950. At the age of 15, she went to see Jean-Luc Godard’s “Pierrot le fou” at the cinema with her friend and future producer Marilyn Watelet, amused by the film’s title. It was a revelation and the birth of her ambition.

At the age of 18, she directed the short film “Saute ma ville”, earning the support of André Delvaux and Eric de Kuyper. The story of a teenager who locks herself in the kitchen and acts in increasingly incoherent ways, throwing everything away and shining her shoes and then her legs next to a Manischewitz box.

Chantal moved to Paris after the shoot, hoping to find inspiration there, which never left her in Paris, New York, Brussels, Tel Aviv, Germany, Eastern Europe and even on the Mexican-American border.

At the age of 23, she directed “Je, tu, il, elle” (I, you, he, she) with Niels Arestrup and Claire Wauthion, a tale of anxiety, wandering and the reunion of operatic bodies. Two years later, Chantal entered the big leagues once and for all with “Jeanne Dilman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles”. Delphine Seyrig leads an ultra-ordered life, covering up her silences and wounds, bringing up her son alone. A life without pleasure, until something unexpected happens. In 2022, this work was voted best film of all time in the ten-yearly rankings drawn up by “Sight and Sound”, the magazine of the British Film Institute.

In “Pierrot le fou”, Jean-Paul Belmondo asks Samuel Fuller to define cinema. The director replies that it was an emotional battlefield. Perhaps this is why Chantal Akerman is one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. Her camera presents love and humour, songs and silences, deep thoughts and nagging worries through a gaze that is both mischievous and gentle. Ahead of her time, ahead of our time too, between the reconstruction of a generation and their children’s quest for pleasure and self-assertion, who fear the return of the dark ages. Sylviane Akerman, Chantal’s sister, now preserves her memory, notably through a foundation.