The construction of the Memorial of the Shoah in France began in 1953, by international subscription, on land made available by the City of Paris. The origins of the project can be traced back to Isaac Schneersohn’s initiative in 1943 to bring together 40 people involved in Jewish life in France, which was still occupied, in order to create a clandestine archive. The aim was to set up a structure to gather material evidence of the persecution of the Jews and pass on this history. The aim was also to create material that could be presented at the trials of collaborators after the war. This was the birth of the Centre for Contemporary Jewish Documentation. This work, carried out in particular by the historians Léon Poliakov and Joseph Billig, proved essential during the trials, including the Nuremberg trial.

In 1950, Isaac Schneersohn decided to create a memorial tomb for the victims of the Shoah: the Memorial to the Unknown Jewish Martyr (MMJI), which was inaugurated in 1956. On 24 February 1957, ashes from the extermination camps and the Warsaw ghetto were solemnly laid in the crypt of the Memorial by Chief Rabbi Jacob Kaplan.

Thanks to the support of the Foundation for the Memory of the Shoah, the City of Paris, the Ile-de-France region and the French government, the Memorial was able to expand in 2005 to include a permanent exhibition, temporary exhibitions, reading rooms, a library, a multimedia area and an auditorium. In this auditorium, a number of events were organised in 2024 in tribute to the victims of the genocide in Rwanda. At the entrance to the Memorial is also the Wall of Names, with the names of the Jews deported from France.

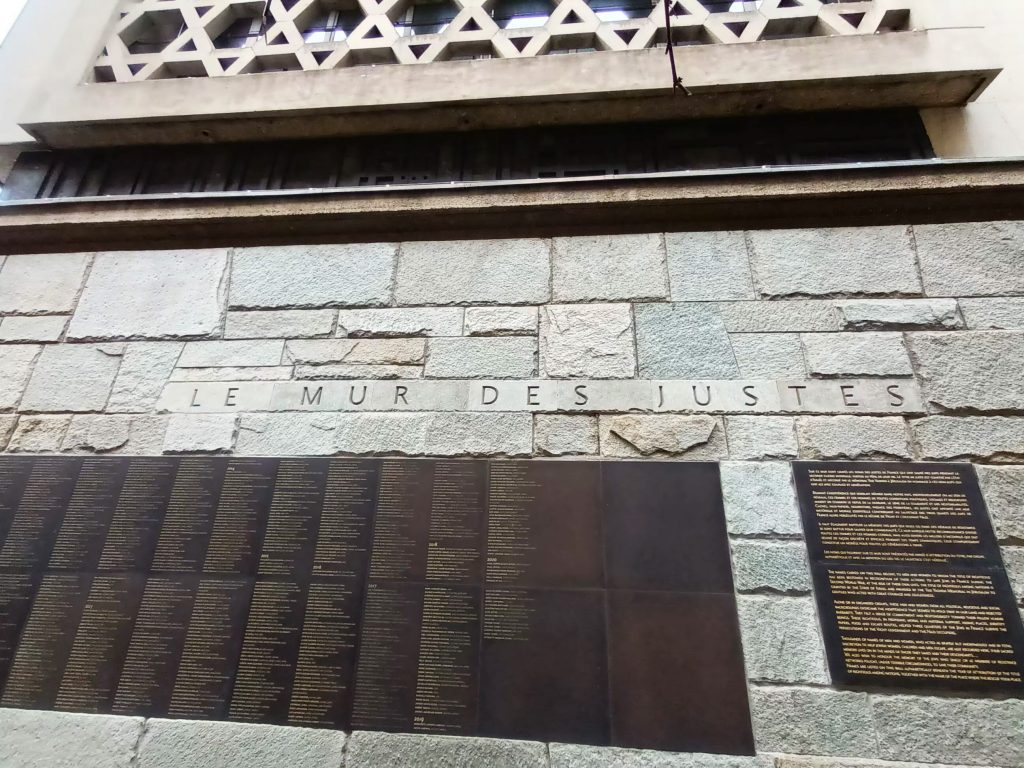

The façade features a text in French, Hebrew and Yiddish in memory of the victims of the Shoah, as well as a Wall of the Righteous, in tribute to the courageous people who risked their lives to save Jews.

Permanent exhibition

The permanent exhibition is located on the 2nd basement level. The room is divided in two. On the left, it traces the history of the Jews of France. On the right is a European perspective.

Left, it begins with a description of Jewish life in France before the war. The panels tell of the very early Jewish presence in France, probably dating back to Roman times. There are also key dates in the history of the Jewish presence in France, both in terms of acceptance and expulsion, tolerance and intolerance, depending on the era, the regents and the conflicts between the political and religious powers.

We discover a host of small portraits showing the diversity of Jewish communities at different times and in different regions, as well as the diversity of personalities. From industrialist André Citroën and writer Tristan Bernard to boxer Victor Young Perez and the artists of the Paris School who gathered at La Ruche, not forgetting philosopher Henri Bergson and the MP who would become head of government, Léon Blum.

French Judaism naturally benefited from the spirit of 1789. The emancipation and confirmation of Jews as French citizens with equal rights. Then Napoleon’s establishment of the Grand Sanhedrin. This spirit of attachment to France and its values was extended and accentuated with the 3rd Republic. This strengthened the place of Jews within the French nation. All these different panels describe the political, cultural and religious aspects of French Judaism, without forgetting the periods of doubt and fear. Particularly at the time of the Dreyfus trial.

Opposite these panels describing the history of the Jews in France, we discover the panels tracing the history of anti-Semitism in Europe. In the middle of the first part of this room, a film on anti-Semitism is shown on a screen.

The second part of the room is devoted more specifically to the period of the Shoah. Firstly, the behaviour of French Jews facing the rise of Nazism in the 1930s. Then, the reception of refugees in France fleeing Nazism, including the key events of that period. Notably the assassination of Ernst vom Rath by Herschel Grynszpan, but also a photo of a large meeting of the Lica, the forerunner of the Licra, with the message ‘Standing up against hatred’. We then see newspapers and other writings that spread anti-Semitic thought, inspired by various conspiracy theories depending on the hatemongers: world domination, the desire to sell the country to either the communists or the capitalists, the lack of patriotism according to some, and conversely a supposedly bellicose patriotic attitude…

The next panels present the general mobilisation and the famous call to enlist for France. Then came the defeat, the calls for a census of Jews, the round-ups and the construction of internment camps, notably Drancy. We also see the infamous poster for the exhibition ‘The Jew and France’. This exhibition was held at the Berlitz Palace from 5 September 1941 to 11 January 1942. It propagated numerous accusations against Jews, in particular their supposed “omnipresence” in all spheres of society, especially cultural. And the purpose of this omnipresence:” the conquest of the world” symbolised by the poster.

In this respect, Marcel Dalio, the great actor of ‘La Grande illusion’ and ‘La Règle du jeu’, who had already incurred the wrath of the anti-Semitic press by playing these two roles, is highlighted in this exhibition. Forced to flee France for America, when he learned on the other side of the Atlantic that he had been cast in this exhibition, he jokingly replied that “even if he’s no longer shooting in France, I’m still on the bill”.

This obsession with omnipresence was also mocked in the 1980s by the great comedian Pierre Desproges. In a bit, he said that ‘all doctors are Jewish, otherwise you wouldn’t have a diploma, except perhaps Doctor Petiot. All lawyers are Jewish, all the archbishops of Paris are Jewish…’. A joke about Monseigneur Lustiger, who was of Jewish origin.

The next panels describe the terrible year 1942, when the deportations of Jews from France began. With numerous portraits, faces, names, stories, badges, notebooks, notes, letters… Confronting the desire to dehumanise the Jews in France during the Shoah, the Memorial gives these Jews back a name, a face, a story, a memory. And shares them.

At the far right of this first large room, the rise of Nazism in Germany is described. The way in which Hitler succeeded in taking over many European territories and applying his policy of terror. The first discrimination against Jews. Their exclusion from civilian life, then their forced ghettoisation, the war and the massacres in the concentration and extermination camps, but also in the forests.

The next room details the deportation to Auschwitz. With a large map tracing the route of the deportation trains to the camp in Poland, near Krakow. There are also many photos of people arriving from the convoys, and the clothes they wore.

The next room plunges into darkness and is dedicated to the testimonies of deportees, presented on several screens. Among them Simone Veil, who was arrested in Nice at the age of 17 and deported to Auschwitz. Simone Veil describes arriving at the camp with her mother and sister. How they narrowly escaped being sorted, the terrible experience of the camp and the death of her mother. A British soldier who liberated the camp asked if she was married, thinking she was over 40 when in fact she was half that. Simone Veil recounts that she quickly regained her physical strength, but that emotionally something remained broken forever. And forever there.

The next room describes the looting of Jews in France and Europe, and the behaviour of civil society in Germany and France. The collaboration of different, often zealous, guilds, whether judges, doctors, gendarmes, journalists… But also the courage of the Resistance fighters in Germany and throughout Europe, some of whom belonged to these guilds. And, of course, General De Gaulle’s 18 June Appeal. Calling on the French to join him in continuing the fight against Germany. In the same room, extracts from Claude Lanzmann’s film Shoah are shown. In 1985, this film enabled the general public, as well as historians, researchers and students, to gain a better understanding of this painful history.

For while there was a great silence on the part of individuals and corporations, this silence was sadly shared by many nations and religious authorities, as we are reminded in the next room. And in the face of all these obstacles and repression, we also see the courage of individuals, anonymous people and associations… The OSE, for example, which organised the escape of Jews from France, mainly children, by hiding them in farms. There were also similar initiatives by youth movements such as the Eclaireurs Israélites and Hashomer Hatzaïr.

When the danger was too great, too threatening, too close, the escape continued, no longer to remote villages, but across borders, whether it was the Swiss network that crossed the border between Annemasse and Geneva or the Varian Fry network by sea from Marseille. But also by land in Spain and Portugal, two dictatorships at the time, sometimes playing a shady game of ‘neutrality’. Franco and Salazar let certain Jews pass under certain conditions, so that they could take a boat from Lisbon to the United States, Cuba, Venezuela, Jamaica. Haiti and other destinations. A diary from the period shows the life of these Jews in Lisbon, waiting for the boat, in particular the Serpa Pinto, which made numerous round trips to ensure the survival of these hunted Jews.

Many adults and even teenagers remained in occupied Europe and took up arms. They joined the maquis and the many forms of resistance, as described in the next room of the permanent exhibition: the armed resistance and the resistance in written form in order to keep the archives. This was done in order to keep the names of the victims and then show the world the truth of these atrocities. Like the work of historian Emanuel Ringelblum, founder of the underground archives of the Warsaw ghetto. And the courage of doctor Janusz Korczak, director of an orphanage who stayed with the children when they were arrested and deported by Nazi troops.

It also looks at the wide range of activities of the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee (JDC). This was very active in the Resistance, but also in rebuilding Jewish life in Europe. Panels describe the courageous Warsaw ghetto uprising. How walled-in, starving, sick and exhausted people took up arms and fought for weeks against the German army. Sometimes for much longer than some nations.

Screens broadcast the words of the Righteous Among the Nations. Some twenty portraits of men and women from different regions of France.

The next room is dedicated to the Liberation, memory and sharing. But also the trials of some of the perpetrators of these crimes in France and Europe. In particular, the Nuremberg trials. Then, we see the first commemorations and tributes to the combatants. The difficulties of sharing this memory between those who need not to turn away, not to look back, in order to survive, to live. This resilience, a form of revenge on the will of destruction, through the beautiful personal and above all generational life, the following generations of children being born in (once again) free countries. Children who are protected, even over-protected, in response to what their parents experienced when they were children.

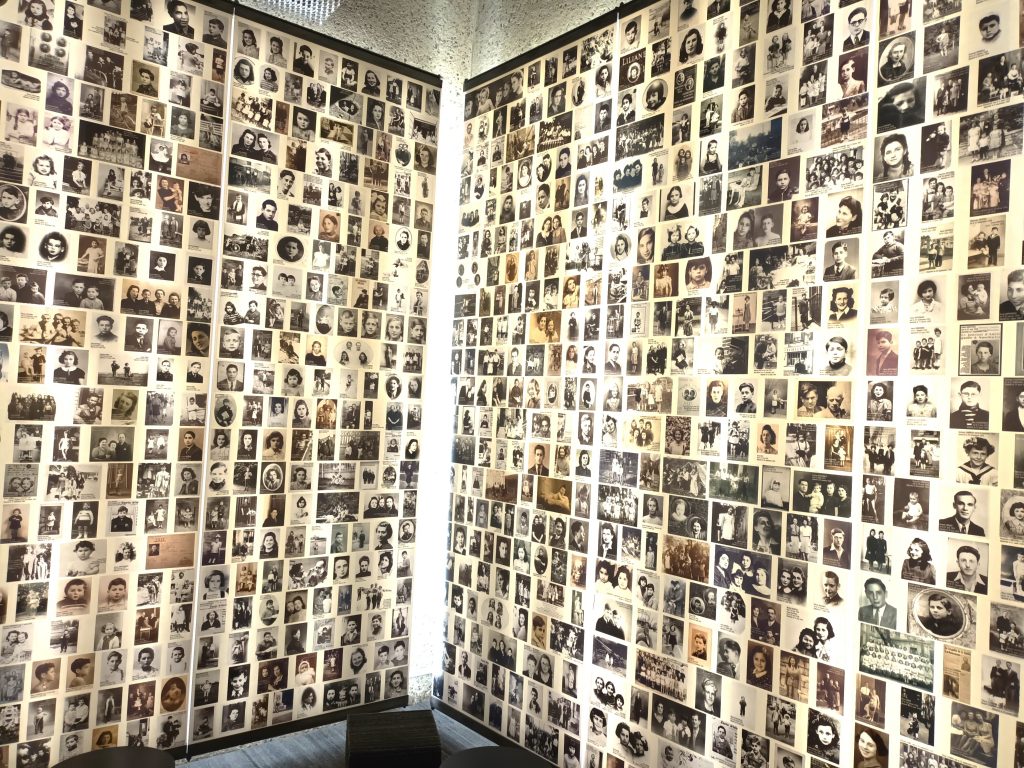

The last room in the permanent exhibition is dedicated to Jewish children. These 11,000 children were deported from France. This memorial is made up of over 4,700 photos from family albums, public and private archives collected by Serge Klarsfeld and the Memorial of the Shoah.

Temporary exhibition

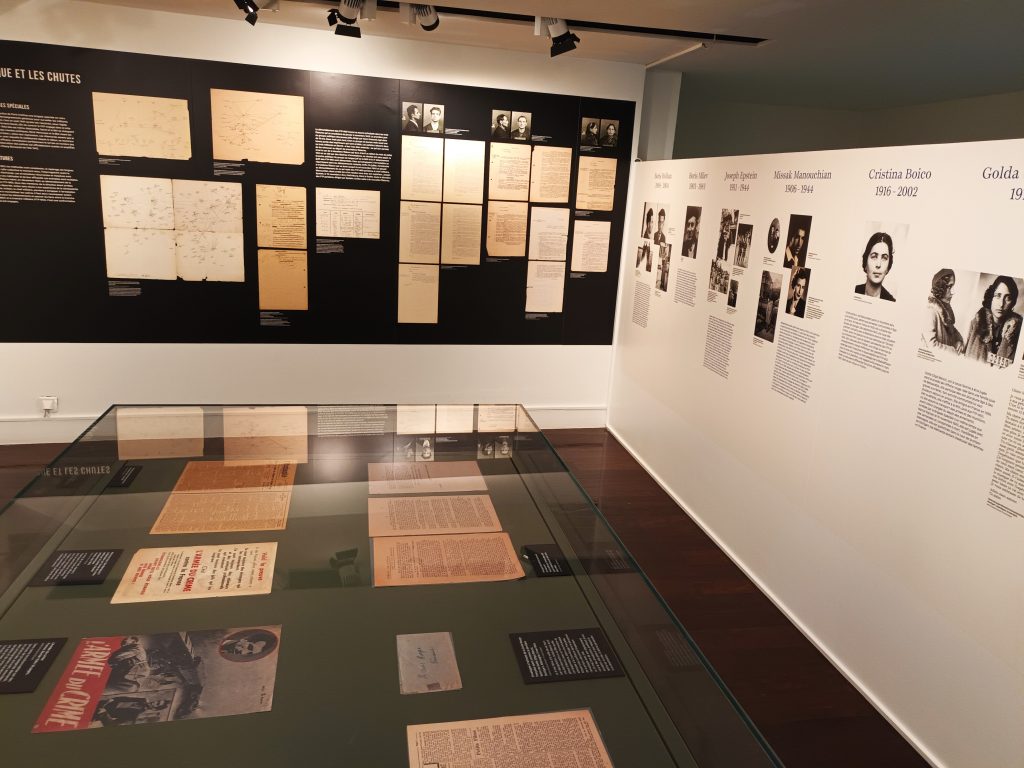

The temporary exhibition at the Memorial of the Shoah opens with the “Red Poster”. This exhibition was organised around the Pantheonisation of Missak and Mélinée Manouchian, which took place on 21 February 2024. We are greeted by the famous poster bearing the words ‘Liberators?’ seeking to undermine the Resistance fighters. Those who were part of the FTP-MOI, insisting on their foreign origin or their ethnic or religious affiliation, nicknamed ‘the army of crime’. A name taken up by Robert Guédiguian for the title of his beautiful film in tribute to them, made in 2009. The men and women involved included Jews, Communists, Italians and Armenians, all united behind their leader, Missak Manouchian.

The exhibition begins with the activities of the FTP-MOI in Paris and the Paris region, explaining the historical context. How, following the break-up of the German-Soviet pact, the PCF officially began the armed struggle. Even though individual Communists had joined the Resistance long before. Three structures were organised in Paris: the Youth Battalions. The Special Organisation and the OS-MOI, made up of foreigners. We find out how the latter was structured.

A map describes their actions in 1943. We also discover the shadowing and tracking of resistance fighters and how the FTP-MOI tried to foil the authorities’ plans to catch them. There are many portraits of these recruits. Notably a young man of 19 who was to become a famous trade unionist, Henri Krasucki, but also Joseph Epstein, Cristina Boïco, Olga Bancic, Marcel Rajman, Roger Rouxel, Rino Della Negra… Between these panels and descriptions, a glass table displays articles from the period, in particular press cuttings from the newspaper l’Humanité evoking the actions of these resistance fighters, but also accusatory brochures published by the German propaganda services.

The exhibition continues with a description of the activities of foreigners involved in the fight against Nazi Germany since 1939. A map shows the locations of the internment camps in France. Most were located in the south and around Paris.

In the next room, not linked to the exhibition, you’ll find the cabinets containing the files used to register Jews during the war. Opposite this room is the Memorial’s crypt, in the shape of a black marble Star of David, symbolising the 6,000,000 Jews murdered during the Shoah. This room also features a model of the Warsaw ghetto, with the points of Jewish resistance marked.

The exhibition devoted to foreigners in the Resistance continues in a small room above the crypt. It shows the propaganda campaigns around the Red Poster. The trials and executions of Resistance members. The main trial took place from 15 to 18 February 1944 at the Hôtel Continental in Paris. 23 of the accused were sentenced to death, 22 of whom were shot on 21 February at Mont Valérien. Olga Bancic was transferred to Stuttgart to be guillotined.

This temporary exhibition also highlights the personal initiatives of courageous people, organised initiatives such as those of Varian Fry, an American diplomat based in Marseille, who helped to save 2,000 people, artists and writers who were open opponents of Nazism or Jews. He helped them leave France for the United States. Thanks also to the help of the American Vice-Consul in Marseille, Hiram Bingham. Other American associations, in particular the YMCA with its delegate Tracy Strong, tried to prevent the transport of internees from the South of France to the Drancy camp. Not forgetting the story of Friedel Bohny-Reiter, a member of Secours Suisse who cared for and saved Jewish families interned at the Rivesaltes camp, as mentioned in the story of Éric Schwam on the JGuideEurope page devoted to Le Chambon-sur-Lignon.