Metz is surprising for many reasons. Firstly, the richness of its medieval architecture and that of subsequent centuries, influenced by numerous conquests and reconquests. With its palaces, symbols of authority, protective fortifications and bridges to other shores and cultures that blend harmoniously. Metz is anything but a city with a museum-like central district. It’s a city whose cultural continuity has been preserved and stimulated, to the delight of tourists and the pride of the locals.

A city famous for its splendid cathedral, its lively Place de la Comédie and Place Saint-Jacques, the homes of François Rabelais, Paul Verlaine and André Schwarz-Bart and its many houses built with Jaumont stone. And of course its prestigious museums, including the Musée de la Cour d’Or tracing the history of the city and the Centre Pompidou-Metz, tracing the artistic link between past, present and future, as it did in 2019-2020 with its splendid exhibition dedicated to Sergei Eisentein.

The Jewish presence in Lorraine appears to date back to ancient times. However, it is only documented in Metz in 599 in correspondence between the Pope and the kings of Austrasia. The main sites devoted to Metz’s Jewish cultural heritage are located in a relatively small area, between the synagogue and En Jurue , rue du ghetto, where there was probably a very old synagogue, where the ghetto gate can still be seen and where André Schwarz-Bart lived. Nearby, in the Cloître des Récollets, are the municipal archives of Metz, very useful for researchers.

Another must-see place for learning about the history of Metz is the Cour d’Or Museum , at the intersection of the triangle formed by the cathedral, the cloister and the synagogue. Its many rooms allow visitors to discover 2,000 years of Metz history, thanks in particular to Gallo-Roman statues and mosaics, medieval finery and weapons, and modern paintings by the School of Metz.

There is also a room dedicated to the Jewish cultural heritage of Metz. The ‘Perennial Memory’ project was launched at the museum in 2023, with the aim of renewing the museography of the history of this community. The project was launched in partnership with the European Days of Jewish Culture, under the impetus of its regional president, Désirée Mayer, and with the participation of artist Jean-Christophe Roelens. The harmonious presentation combines works of art, antique objects, interactive technological content, photos and explanatory texts, enabling visitors to appreciate the diversity and age of Metz’s Jewish cultural heritage.

History of the Jews of Metz

The first official document attesting to the presence of Jews in Metz was a provincial council in the Middle Ages, which prohibited Christians from dining with Jews. However, many Christians did not follow this advice and friendly and intellectual exchanges continued around these tables. Sigebert of Gembloux (1030-1112), for example, consulted Jewish scholars to translate passages from the Bible. This was a time when the region stretching from Champagne to the Rhineland communities of Speyer, Worms and Mainz, via Alsace and Moselle, was home to an extraordinary development of Jewish intellectual life.

The most influential representative of this intellectual golden age in Metz was Rabbenu Gershom. Born in Metz in 960, he became the leading figure in medieval Lorraine Judaism. Nicknamed the ‘Light of Exile’ by Rashi, who was one of his pupils, he ran a Talmudic school in Mainz. He was known for his rulings on the organisation of family life, in particular those prohibiting polygamy and the repudiation of a wife without her consent, which he replaced with divorce in due form. These decrees were gradually adopted by all Jewish communities.

This golden age came to an end in Metz in 1096 with the massacre of 22 Jews from Metz during the First Crusade, including Samuel Cohen, the leader of the community, which consisted of around a hundred families at the time. Many forced conversions took place at this time.

The yeshivot resumed their activities in the 12th century, under the influence of tossafist schools. Among his glorious pupils was Rabbi Eliezer, a tossafist who followed the teachings of Rabbenu Tam and was the author of one of the first attempts to codify Jewish law. Other scholars of the time were the tossafist David of Metz, Judah of Metz and Samuel ben Salomon of Falaise. The scholars of Lorraine maintained numerous intellectual exchanges with both French and German thinkers.

In 1237, foreign Jews entering Metz were obliged to pay special taxes. Until the expulsion of the Jews from the duchy in 1477, the Jews of Metz, like many other communities in France and Europe, were either warmly welcomed or encouraged to leave, depending on the fluctuating socio-economic assessments of political and religious leaders. The Jewish community in Metz gradually disappeared at the end of the 13th century. The only evidence of this period are the houses in the En Jurue street.

From the end of the 15th century to the 17th century, very few individual Jews returned to Metz and very small communities remained in the region. In 1567, the Marshal of Vieilleville granted the Jews the right of residence in Metz, so that they could take part in supplying the army with horses and wheat. Some of them settled in an alleyway (now called rue d’Enfer) between the En Jurue and the Récollets cloister.

By 1604, almost 120 Jews from Metz were living in the city. Fifteen years later, a synagogue was inaugurated. The community began to organise itself from this time onwards and was recognised by an order from the Duke of Valletta in 1624. The new arrivals settled in the Saint-Ferroy district in particular. The Jewish population grew throughout the century, rising from 398 in 1621 to 665 in 1674 and 1,080 in 1698. A Jewish cemetery has been existing for a very long time.

Heavy taxes were regularly imposed on the city’s Jews, as were restrictions on access to employment. In 1670, Raphaël Lévy was tried and executed at Glatigny, accused of ritual murder. Anti-Jewish measures were also taken. By 1717, the Jewish community in Metz had grown to over 2,000, making it the largest in France, thanks in particular to the arrival of German Jews.

The winds of the Emancipation of 1789 also swept through the Lorraine region. It was in this region, also inspired by the work of Mendelssohn and the Haskalah, that the periodical Ha-Meassef had the most subscribers after Berlin.

The minister, Malesherbes, set up a committee to this end, which included Isaac Berr from Nancy and Pierre-Louis de Lacretelle and Pierre-Louis Roederer from Metz. Pierre-Louis Roederer was the instigator of the competition organised by the Metz Society of Sciences and Arts, which asked candidates to consider the question ‘Are there ways of making Jews more useful and happier in France? Three dissertations were awarded the prize: those of Claude-Antoine Thiéry, Zalkind Hourwitz and, above all, Abbé Grégoire (1750-1831). The latter defended access to the rights and duties of citizenship for Jews before the National Assembly. His “Essay on the physical, moral and political regeneration of the Jews” was published in 1789 after winning the Académie prize. Abbé Grégoire also fought against black slavery.

The Emancipation of Jews decreed on 27 September 1791 gave them access to the schools, professions and the obligations shared with every other citizen. Following the Revolution, the Jews of Metz were granted French nationality in 1791 and freedom of worship in 1792. Isaïe Berr Bing became a member of the town council, symbolising this development. The Talmudic School, founded in 1821, became the Rabbinical School of France in 1829, a symbol of the great importance still attached to scholarship in the region. It was transferred to Paris thirty years later.

Throughout the 19th century, the number of members of Judaism in Lorraine fell, to the benefit of the Paris and Lyon regions. By 1853, there were just 1,300 Jews in Metz, three years after the consistory synagogue was rebuilt. One of the most important figures of this period, and proof of the dynamism of Lorraine’s Judaism, was Chief Rabbi Lazare Isidor (1813-1888), who was born in Lixheim and studied rabbinics in Metz. The mathematician and reformer Orly Terquem (1782-1862) and above all Samuel Cahen (1796-1862), the first Jewish translator of the Hebrew Bible into French and founder in 1840 of the journal Les Archives israélites de France.

When the 1870 war broke out, the Jews of Metz enlisted to defend France, as did Chief Rabbi Benjamin Lipman (1819-1886), who, together with the bishop, visited the Jewish hospice where soldiers of all faiths were cared for. Following the German annexation, Lipman and many other Jews opted for exodus. Victory in 1918 brought a peaceful return. The 1870 conflict and the First World War encouraged the arrival of Jewish refugees in Lorraine, particularly in Metz. The Jewish population rose from 2,000 in 1866 to 4,150 in 1931. One of the most important figures of the inter-war period was Chief Rabbi Nathan Netter (1866-1959), who was appreciated for his highly patriotic writings and his concern for the poor.

Following the German attack on 10 May 1940, Metz was bombed. On 10 June, Victor Demange (1888-1971) scuttled his newspaper Le Républicain Lorrain, which was not published until after the city had been liberated. On 14 June 1940, the Moselle prefect ordered the mayor to leave Metz, which had been declared an open city, causing panic among the population, who fled. The Germans entered the city on 17 June and carried out a systematic Germanisation, with Alsace and Moselle Lorraine being effectively annexed. German became the official language, streets were renamed and statues of French heroes were removed.

The expulsions and despoilments quickly began, as did the recruitment of young people and the total control of the Gestapo. During this time, Resistance movements sprang up in Metz and the surrounding area, notably around the teacher Jean Burger (1907-1945). Fort Queuleu was transformed into an internment and transit camp. Metz railway station was used as a transit point for many deportees from French camps to German camps.

Another war, another rabbi hero: Elie Bloch. Born on 9 July 1909 in Dambach-la-Ville, this son of a rabbi became a textile engineer before also opting for a career in the church. He was appointed deputy rabbi of Metz in 1935, in charge of youth affairs. With the help of Father Jean Fleury, chaplain to the Gypsies in the Poitiers camp, he organised the escape of many families to the countryside, as well as solidarity networks. On 17 December 1943, Elie Bloch, his wife Georgette and their 5-year-old daughter Myriam were deported and murdered in Auschwitz, as were thousands of other Jews from Metz. The street on which the synagogue stands now bears her name.

On 20 November 1944, the first American troops entered the north and south of Metz, accompanied by French soldiers. The city was liberated the following day. On 22 November, American General Walker handed the city over to the French authorities and Mayor Gabriel Hocquard resumed his duties.

The Jewish community struggled to rebuild after the war, having lost many of its members. In the 1960s, Jews from North Africa helped to breathe new life into the community.

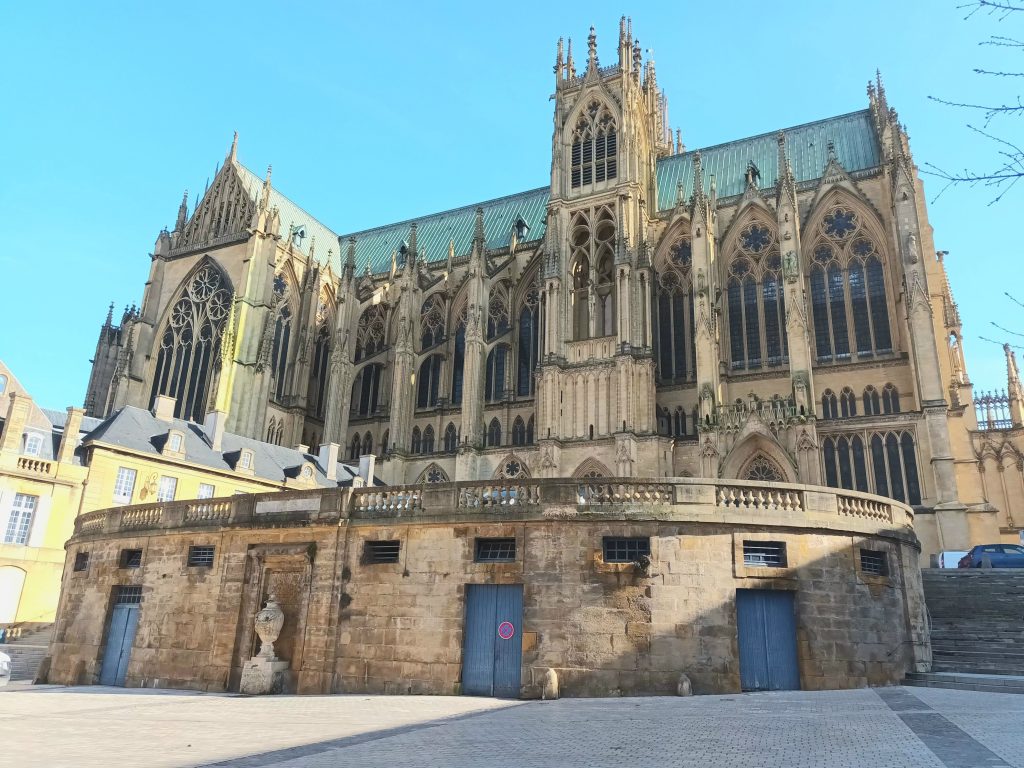

Just 700 m from the synagogue, opposite the town hall, is Metz Cathedral, probably one of the most beautiful in France, an impressive edifice 123 m long and 88 m high. Its 14-metre-high windows let in plenty of light and showcase the stained-glass windows created by numerous artists from the 13th century to the present day.

The stained-glass windows include those of a certain Marc Chagall.

In the two windows of the north apse, Chagall revisits episodes from the Bible, from the sacrifice of Isaac to the concerns of the prophet Jeremiah, including Jacob’s struggle with the angel, the Tables of the Law received by Moses and the song of David. A work dating from 1959.

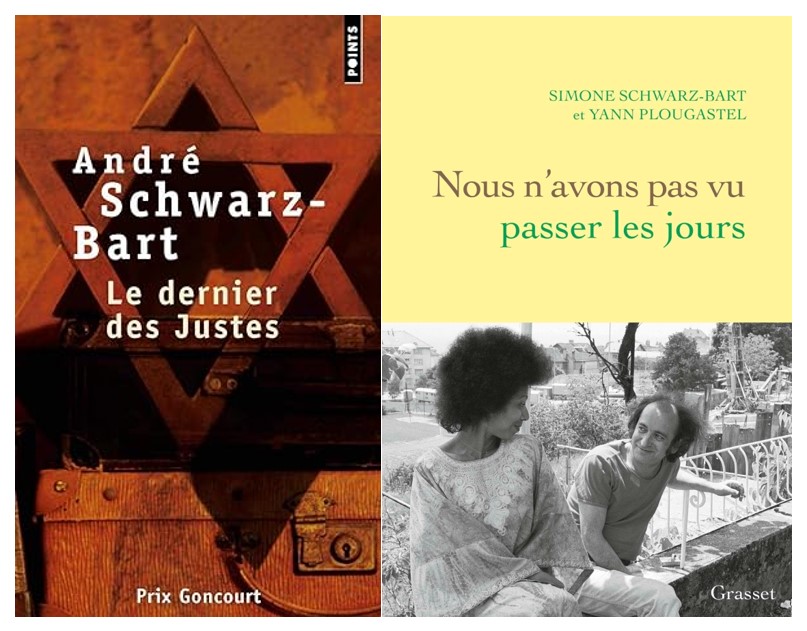

The year the Prix Goncourt (France’s most prestigious book award) was awarded for Le Dernier des Justes to the greatest contemporary Jewish figure from Metz: André Schwarz-Bart (1928-2006). The author was born in Metz on 23 May 1928 and spent part of his childhood in a house at 23 En Jurue. His parents and one of his brothers were arrested along with other family members and deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered. André Schwarz-Bart joined the Resistance in 1943. As an FTP fighter, he took part in the Liberation of Limoges.

After the war, he resumed his studies and worked in tailors’ workshops and in the factory. It took him eight years to write his book, a painful look at his past and the loss of his family. Following the publication of Le Dernier des Justes, he devoted himself to denouncing slavery and sharing the civilisations of black peoples. He co-wrote La Mulâtresse Solitude with Simone Brumant, whom he married in 1961 and with whom he moved to Guadeloupe in 1974. In a book published in 2019, Simone Schwarz-Bart looks back on their beautiful story of love and literature.

After two years of renovation work, the Metz synagogue reopened its doors in October 2025. More than 600 people attended the ceremony on Sunday, welcomed by a song performed by the Strasbourg synagogue choir. The site and the renovation work are symbolic of the new ‘Jewish Heritage Programme’, supported by the Heritage Foundation and the Edmond J. Safra Foundation, which aims to preserve and promote sites linked to Jewish history in France. The work was carried out both outside and inside the building.

Source: Le Républicain Lorrain

In Metz, we met Désirée Mayer, President of the JECJ-Lorraine, a key figure in the region’s cultural life, and one of the driving forces behind the JECJ-Lorraine board’s redesign of the room dedicated to the Jewish cultural heritage of Metz at the Musée de la Cour d’Or, Metz Métropole.

Jguideeurope: How did the project to create a room in the Museum devoted to the Jewish history of Metz come about?

Désirée Mayer: Like all good and lively projects, this one has several sources. There was a Jewish room in the museum, which was almost empty and unattractive. Before that, there was a local Jewish history that just wanted to be told, ritual objects that just wanted to embody it and all kinds of memorial traces that were looking for expression. Finally, there was the determination of the European Days of Jewish Culture – Lorraine team, bolstered by the benevolence and extreme competence of the management and staff of the Museum of the Cour d’Or, Metz Métropole. But we are not forgetting the inspiring model of the Rashi House in Troyes, or the many institutions, foundations and sponsoring associations that understood the value of the project and supported it.

What changes were made in 2023?

At the instigation of the Museum’s management, EDJC-Lorraine had photographs taken of the interior of the Metz Consistorial Synagogue and the Holy Ark, so that from the moment visitors arrive, they are greeted with a sense of interiority. With European aid and the support of patrons, in particular the Demathieu Bard foundation and the Bnaï-Brith Elie Bloch association, we were able to provide the museum with a touch-sensitive digital table, with software that allows visitors to immerse themselves in the Bible. Visitors, especially young people, love it. The room supervisors have become its dedicated mediators. Finally, the association exhibited a magnificent ‘Salon Judaïca’, created for the EDJC-Lorraine by an artist from Metz, Jean-Christophe Roelens. This artistic and educational exhibition, inspired by Rodchenko’s ‘Workers’ Club”, was enhanced for the occasion by a significant element symbolising Metz and Judaism.

Transmission has always been central to your commitment to teaching and cultural action. Is that what motivated your involvement in this project and in the JECJ?

More than any other project, this undertaking to refurbish the Jewish Room at the Museum of Metz fulfils our desire to pass on and share Jewish culture. The enduring nature of this prestigious institution, within an in-situ museum with a history spanning two millennia, is bound to resonate with the universal values of Jewish culture and spirituality. The large number of visitors, particularly young people, gives us hope that here, through this action, transcendence and descent can begin an infinite dialogue. This is exactly the eternal dream of the ‘passers’ and of those who wish to pass on their heritage.

What little-known place or person associated with this heritage do you think deserves to be highlighted?

Your question tortures me. For if the Eternal is One, all other references can only be plural. Without making any Christian claims, please allow me to evoke a trinity, or even a quartet. First, of course: the Metz consistorial synagogue, rich in history and symbolism, and which – thanks to the Heritage Foundation, the State and the City of Metz – is currently being renovated. This mid-19th century building will once again become a jewel. Secondly, I would highlight the stained-glass windows by Chagall in the Cathedral of Saint Etienne in Metz, particularly the atypical triforium in the left transept. Finally, I would choose the memoirs of the chronicler Glickel von Hammeln and, two centuries apart, the formidable Last of the Righteous by the Jewish author from Metz, André Schwarz-Bart.