Like the opera house in the business district, Frankfurt is above all a city of encounters and fruitful exchanges in all fields and between different populations since the Middle Ages, but also a witness to and actor in great violence, as was the case during the Holocaust.

From Goethe to the prestigious university that bears his name, from the Main River, which flows alongside museums and rebuilt neighbourhoods, to its international airport, the fourth largest in the world and the fourth largest financial centre in Europe, this city of less than one million inhabitants offers visitors a chance to (re)discover and find inspiration, between the past and the future, a theme so dear to Hannah Arendt, like this artistic vision of David and Goliath in the heart of the shopping district…

History

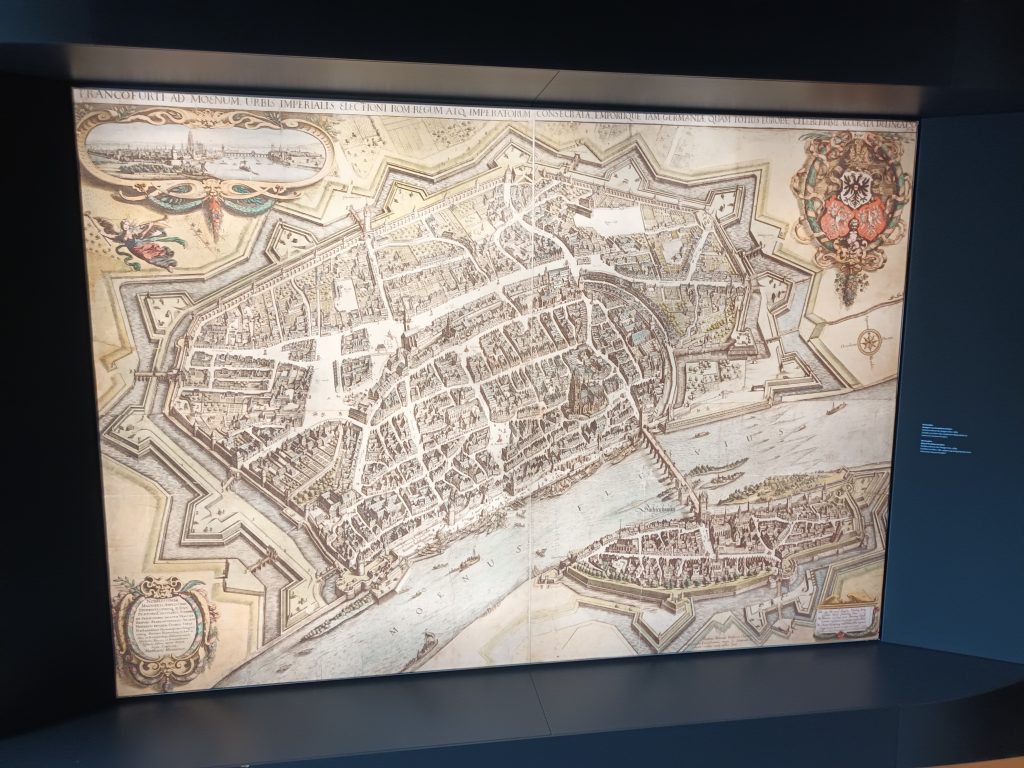

The Jewish presence in Frankfurt dates back to the 12th century. The oldest residences were located in the city centre. As a free city of the Empire, Frankfurt welcomed Jews from 1150 onwards, mainly merchants from Worms. Over time, they were victims of pogroms, expelled and protected according to the political decisions of the day.

In 1460, the Frankfurt City Council decided to establish a Jewish ghetto. Over the next two years, the hundred or so Jews living in Frankfurt were forced to move to what is now known as the Judengasse (‘Jewish alley’). This was an area of the city separated from the rest by walls, where up to 3,000 people were crammed together in 1610. Large yeshivot developed there, attracting students from all over Europe, as in the cities along the Rhine.

Despite such restrictions, there was considerable interaction between Jews and Christians in various areas, including work and crafts, particularly the production of Jewish ritual objects by Christian craftsmen. There were also theological encounters between Jewish and Christian thinkers, not to mention moments of celebration and reunion in the city’s establishments.

Forced to live in the ghetto, institutions were developed to manage social, educational and religious affairs. Within this life cut off by the gates of the ghetto, trades diversified, whether in commerce, crafts, teaching, domestic service, etc. Although from the 17th century onwards, many Jews worked as merchants, particularly at fairs, trading textiles, spices and metals.

In the 1980s, ancient documents written in Yiddish were found in a geniza in the Veitshöchheim synagogue. Literary and musical production was very rich during these years of life in the ghetto.

It was not until the turn of the 19th century that Jews were allowed to leave the ghetto. During this century, Frankfurt became one of Europe’s main publishing centres for works in Yiddish. The continuity of exchanges and mutual inspiration between Jewish and Christian populations continued in the literary and musical fields. For example, Jewish songs were composed to Christian melodies and Christian tales were inspired by Yiddish works.

At that time, Mayer Amschel Rothschild (1744-1812), a student from a modest family, became interested in mathematics and finance. He did an internship at a bank in Hanover. Becoming a money manager in the Frankfurt ghetto, he diversified his activities and made a name for himself in the world of finance and at court. His five sons settled in London (Nathan), Paris (James), Vienna (Salomon), Naples (Carl) and Frankfurt (Amschel) to develop the dynasty known as much for its success as for its generosity.

Officially authorised to live in areas other than the Judengasse in 1811, the Jews first moved to the surrounding Ostend district and then a little further into the city. They played a full part in the cultural, educational, social and economic development of Frankfurt. But it was not until 1864 that they were considered fully equal citizens.

This gradual evolution can be seen in the works of Moritz Daniel Oppenheim (1800-1882), the first Jewish painter to receive an academic art education in Germany. His paintings depict family and religious scenes as well as portraits. They also depict figures participating in cultural and literary life, representing the way in which Oppenheim and many Jews fully embraced the emancipation that was finally within their grasp. In this spirit of encounters, a painting by Oppenheim from 1864 depicts Felix Mendelssohn Bartholdy’s visit to Goethe. The Jewish musician was proud to play for the prince of poets.

Jewish religious life in Frankfurt at the time was marked by this desire for initiative and diversity. In the 19th century, Rabbi Leopold Stein introduced liberal reforms. This encouraged passionate theological debates with Samson Raphael Hirsch, who was of an important figure of the neo-orthodox movement. Various places of study emerged, including the ‘Free Jewish Study House’ where Martin Buber (1878-1965) taught, led by Franz Rosenzweig.

Three synagogues represented this rich intellectual confrontation: the Masorti synagogue on Börneplatz with its rabbi Nehemias Anton Nobel (1871-1922), inaugurated in 1882; the neo-Orthodox Friedberger Henninger Synagogue of Rabbi Salomon Breuer (1850-1926), inaugurated in 1907; and the liberal Westend Synagogue, where Rabbi Georg Salzberger (1882-1975) established a Jewish adult education centre, inaugurated in 1910. When the First World War broke out, many Jews from Frankfurt fought in the armed forces.

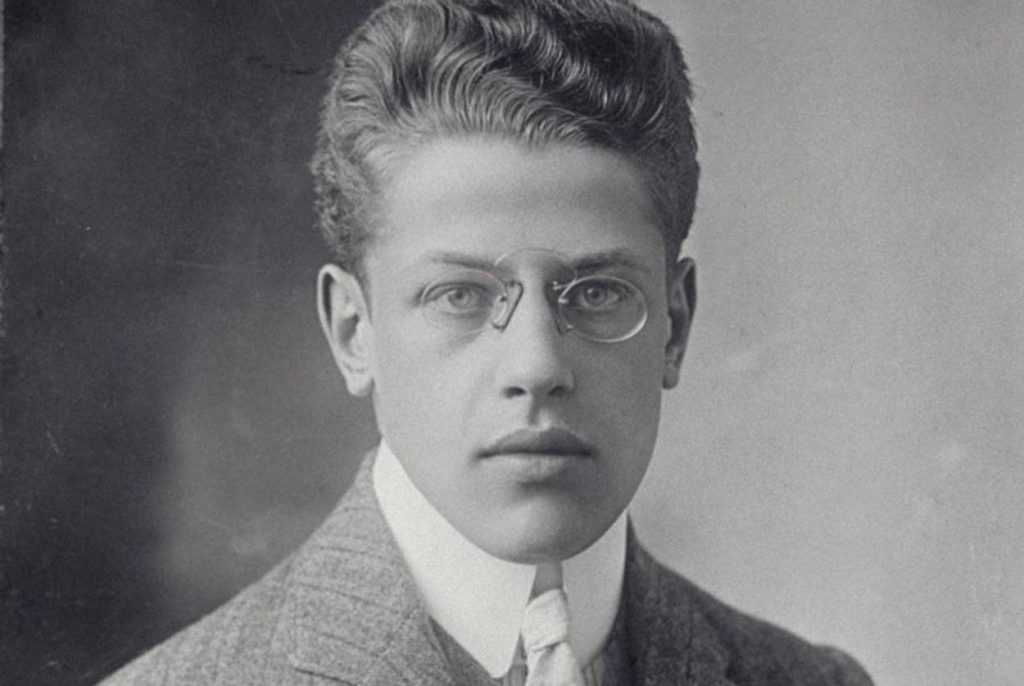

A major intellectual upheaval emerged in the 1920s at the University of Frankfurt with the meeting at the Institute for Social Research of great thinkers, mostly Jewish, the most prominent of whom were Max Horkheimer, Theodor W. Adorno, Herbert Marcuse and Erich Fromm. Encouraging a multidisciplinary approach and a non-dogmatic Marxist vision, as well as taking into account the evolution of society and the cataclysms caused by the wars, the Frankfurt School was born, whose most famous disciple today is Jürgen Habermas.

Nearly 30,000 Jews lived in Frankfurt between the wars. When the Nazis came to power in 1933, they quickly imposed restrictions on Jews, gradually excluding them from the society to which they had contributed so enthusiastically and in so many areas. This was followed by the pogroms of 1938 and the deportations from 1941 onwards.

Only a few hundred Jews managed to hide, protected by Righteous people. Some of the others managed to flee, but more than 10,000 were murdered in concentration and extermination camps. The synagogues on Borneplatz and Friedberg Anlange were destroyed during Kristallnacht on 9-10 November 1938, along with the Museum of Jewish Antiquities, founded in 1922. Although much of its collection was destroyed by the Nazis, nearly 1,000 objects were recovered and incorporated into the current museum.

80% of the buildings in the city of Frankfurt were destroyed or severely damaged. America played a major role in the reconstruction of the city, as well as in the fight against anti-Semitism. A process of denazification was undertaken throughout the country.

On the eve of Rosh Hashanah in 1945, Rabbi Leopold Neuhaus organised prayers in what remained of the Westend synagogue, the interior of which had been destroyed in the pogrom of 1938. The prayers were held in front of a few survivors and American Jewish soldiers stationed in the city. In 1948, the city and the region committed to subsidising repairs. It was therefore rebuilt and reopened in 1950. Today, it is home to an Orthodox congregation. A room inside the building is used for liberal service.

The desire to honour the memory of the many victims of the Holocaust, but also to highlight the importance of Frankfurt’s Jewish history, led to the creation of a commission to investigate this history, with the help of local authorities. Created in 1961, this commission included Max Horkheimer, Rabbi Kurt Wilhelm and Rabbi Georg Salzberger.

Jewish life was revived in Frankfurt mainly in the 1980s. One of the milestones was the creation of a community centre a few steps away from the Westend Synagogue. As in Vienna, Frankfurt has two museums: the Judengasse , dedicated to medieval Jewish life, and the Judisches , dedicated to contemporary Jewish life. The latter, housed in the former Rothschild Palace, was inaugurated on 9 November 1988 in the presence of German Chancellor Helmut Kohl, marking the 50th anniversary of the 1938 pogrom.

In 1987, during redevelopment work on Frankfurt’s Börneplatz, where one of the former synagogues was located, 19 former houses from the Judengasse were discovered. Opposition arose between the city council, which wanted to erect a municipal building on the site, and people who wanted to preserve these rare traces of the former Jewish ghetto. A compromise was reached and five of these former houses were included in the Judengasse Museum, which opened in 1992. These houses form the central element of the museum.

Following the end of the Cold War, many Jews from Eastern Europe settled in Frankfurt. Today, there are estimated to be more than 6,000 Jews living in Frankfurt.

In 2021, Goethe University Frankfurt inaugurated a department of Jewish studies named in honour of Martin Buber and Franz Rosenzweig. The inauguration took place on the 143rd anniversary of Buber’s birth. He had once taught at the university before being expelled by the Nazi regime.

As was the case in many other places in Europe, Jews in Frankfurt experienced a rise in anti-Semitism at the turn of the 21st century. This anti-Semitism has become increasingly violent since the pogrom of 7 October 2023. Among the regular victims of these attacks is the Maccabi Frankfurt football team. This was also the case during a violent attack in Grunburg Park in August 2025.

The Judengasse Museum

As you walk through the museum doors, you are plunged into the history of this particular place. Such as the day when the synagogue was burned down on Börneplatz. Then we read about the debates concerning the redevelopment of this space. A room shows how the neighbourhood has changed over time. Old objects are on display, including a menorah, a Megillah Esther and the Passover Haggadah, to explain Jewish rituals.

Panels present the property restrictions and heavy taxes imposed on the Jewish population when they lived in the ghetto. Decrees bear witness to the changing status of Jews in Frankfurt.

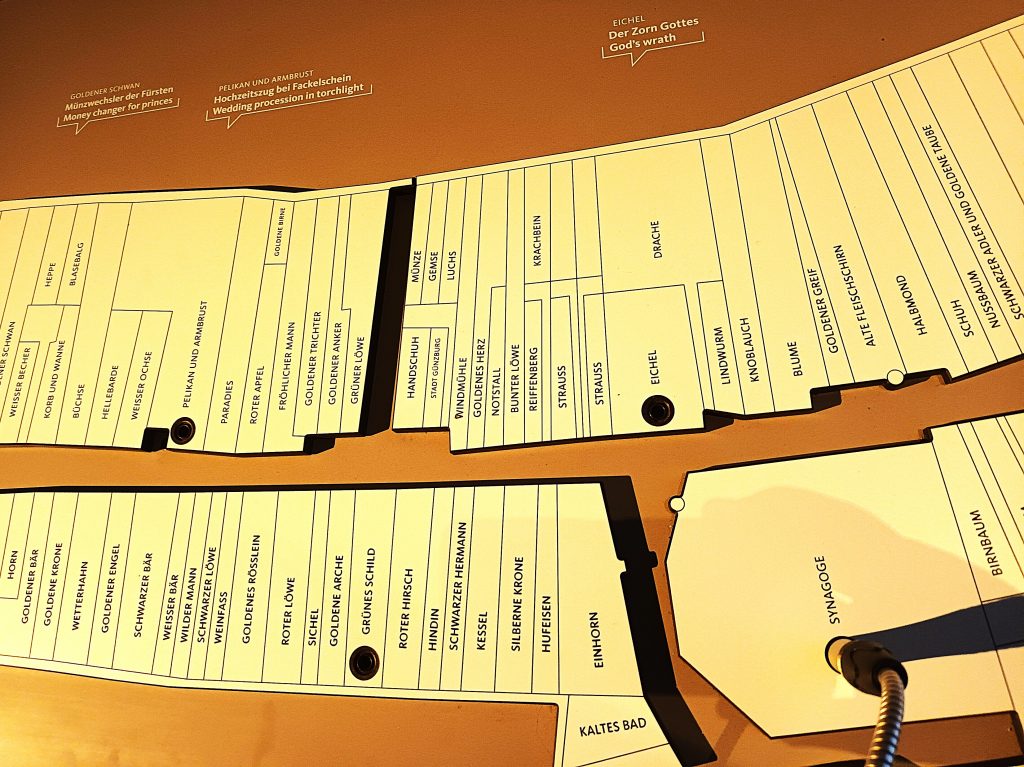

A very interesting feature of the museum is a table on which the former Jewish ghetto is drawn. Visitors can put on headphones and plug them into the holes corresponding to the different dwellings, institutions and shops. Recordings recount the daily life of the Jews at that time, describing the places, their roles and some of the people who lived there.

The museum is on two levels. The lower level houses the foundations of old buildings (houses, wells, mikvahs, etc.) from the ghetto and justifies why the museum was founded. Small books placed next to the seats explain the life of the Jews of yesteryear, as well as certain rituals, such as the preparation of matzos. Among the objects on display on this level are some found during the renovation of the neighbourhood, including an 18th-century circumcision cushion.

One area is dedicated to literature and music, with 13 ancient scrolls on display. Among them is an 18th-century book found in a genizah, with a drawing illustrating the text of a character who looks a little like a heel Marvel superhero. Among the most precious objects is a 14th-century mahzor.

The museum makes a great effort to humanise the ancient life of the Jews of the ghetto, telling personal stories with objects that are just as personal. Maps showing where they lived are also displayed as part of this effort to reconstruct their lives. This shows that the traces of the past are not limited to stones. In the buildings they lived in and between the walls, writings, stories and words were shared by characters sometimes in colour, sometimes in pastel shades, reassured or anxious depending on the period.

On leaving the room, panels tell the story of the Jews of Frankfurt through the centuries, summarised in a few photos of emblematic places and moments. There are other curiosities in this alley, such as pipes used as drains.

Once you have finished your visit to the museum, turn right and walk along the wall of the ancient Jewish cemetery , where stones have been placed in memory of the victims of the Holocaust. To visit this site, you must ask the museum for a key to gain access. As in the old Jewish cemetery in Prague and other German cities such as Worms, there are some very old gravestones.

Between the city’s two Jewish museums is the ‘new old town’, which was restored after the war. Take the time to stroll around and discover a wealth of monuments, including official buildings, places of worship and museums.

These include the beautiful Frankfurt Imperial Cathedral with its impressive organs.

But also the historic Römerberg market square with its festive attractions in summer and winter, the Frankfurt History Museum, the Caricature Museum and the Goethe Museum.

A bronze plaque designed by stonemason Uwe Risch, installed in 2000 at 22 Braubachstrasse, commemorates the persecution of the Sinti and Roma by the Nazis.

The Jewish Museum

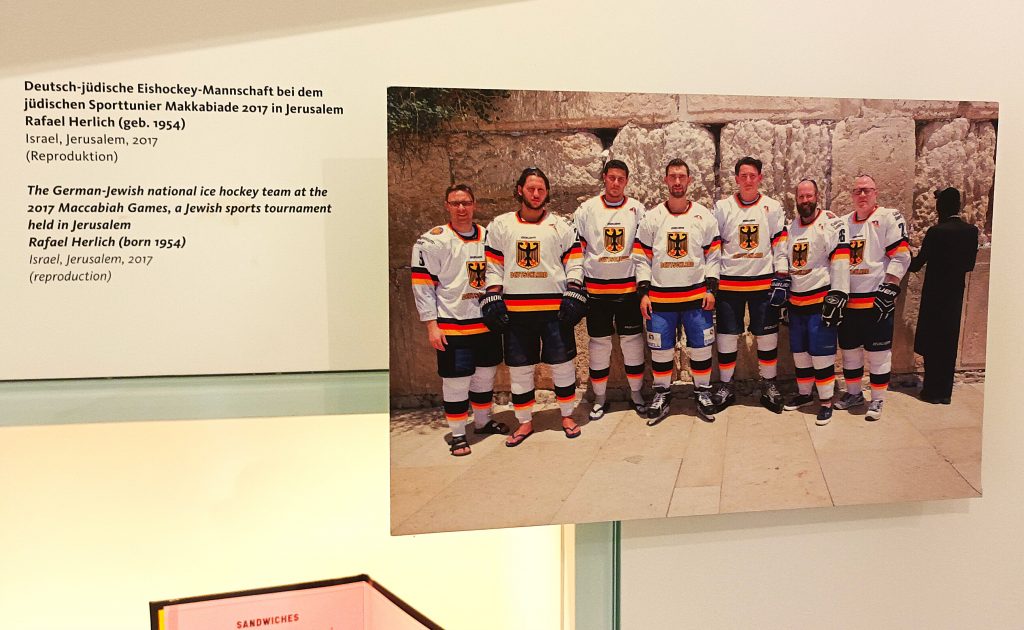

The tour begins on the third floor, a new floor dedicated to contemporary Jewish life in Frankfurt. Visitors are greeted by a screen showing different faces belonging to different generations. Then, as they enter the room, the story of these people is told through old photos and personal objects. Among the moving and surprising photos is one of the German ice hockey team’s visit to the 2017 Maccabi Games. They can be seen posing in uniform in front of the Western Wall, some even with their skates on!

We travel through the 20th century, evoking discrimination, anti-Semitism, the liberation of Frankfurt by American soldiers, and their work to denazify the country and its institutions. But also personal stories of people who managed to survive and believed in a possible return to Germany, as part of the eventual reconstruction of Jewish life in Frankfurt. Among the contemporary symbols of this reconstruction is Maccabi Frankfurt, with its moments of glory, but also the anti-Semitic attacks it has suffered and continues to suffer on a regular basis.

Another complex contemporary issue addressed is the restitution of artworks looted during the war. The museum presents the story of a painting by Matisse, which was stolen and recovered much later…

Leaving the large main hall, visitors enter a series of small rooms. The first tells how the building was bequeathed by the Rothschild family to be used as a Jewish museum. Next are paintings by Daniel Moritz Oppenheim. These include biblical works, such as an impressive Moses, as well as paintings depicting Jewish life in Frankfurt in the 19th century and the great meeting between Mendelssohn Bartholdy and Goethe.

Great minds do not always produce great ideas. The next room is dedicated to infamous anti-Semitic quotes from influential thinkers throughout history. Visitors then discover works by contemporary local artists and learn about the lives of Jewish residents of Frankfurt in the 20th century through a series of postcards, each telling a story.

The second floor of the museum is devoted to Jewish tradition and rituals: a kiddush cup, a shofar, two large menorahs and a parokhet. Another room presents the history of Jewish thought in Frankfurt, which, as we mentioned earlier, was quite rich.

And if you still have doubts or questions about the different currents of Jewish thought that arose and developed in Frankfurt in beautiful harmony, you can ‘ask a rabbi a question’. Combining biblical thought and technological tools, a device allows you to ask rabbis from different traditions questions on a wide range of topics. You can then listen to their recorded answers on these topics, compare them and draw inspiration from different interpretations.

The first room on the first floor is dedicated to the Senger family. Photos and testimonials, as well as the book Kaiserhofstrasse 12, tell the story of this family of Russian origin and what happened to them during the war.

Another room briefly presents the history of the Rothschild dynasty. Its origins in Frankfurt and its development in Europe, as well as all the activities in which the family was involved. Among these activities, the most important was probably tzedakah. This term means ‘justice’ and not ‘charity’, as it is commonly translated. Justice for those who are fortunate enough to succeed in their field, while being generous to others through financial donations, their time and/or their talent. Visitors can discover the history of the five Rothschild sons, as well as the women of the family who played an important role.

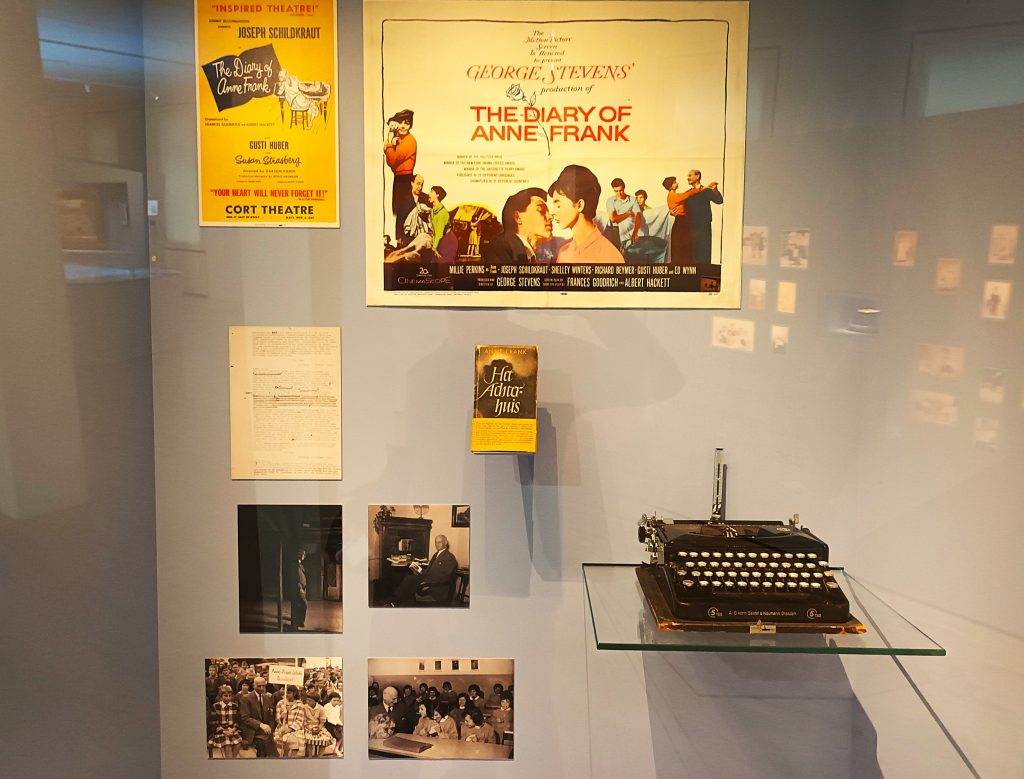

The museum tour ends in the room dedicated to Anne Frank (1929-1945). It tells the story of the young girl and her father, who, after the war, shared his daughter’s writings in a spirit of Tikun olam.

From East to West

During the infamous Kristallnacht, from 9 to 10 November 1938, the Nazis launched pogroms across the country and destroyed many synagogues, homes and businesses belonging to German Jews. Among the synagogues destroyed was the Friedberger Anlage . The authorities built a bunker on its ruins in 1942. It was located in the Ostend district, which was developed in the mid-19th century to accommodate middle-class and working-class tradespeople and artisans.

Many Jews had settled there in the early 19th century, when they were allowed to leave the ghetto. By 1895, Jews made up nearly a quarter of the neighbourhood’s population.

After the war, the bunker was converted into a memorial site, with an area recounting the history of the Jews in this neighbourhood from the early 19th century to the Second World War. On its walls are references to the kibbutzim that were victims of the pogrom of 7 October 2023.

Although Jews tentatively returned to Ostend after the war, they more often chose to settle in Westend. In fact, only a few social institutions remain in Ostend, along with the Baumweg synagogue .

This former building, which housed a Jewish kindergarten confiscated by the Nazis, became a synagogue in 1945.

The Westend district is therefore home to most of the contemporary institutions, as the website of the Jewish community in Frankfurt points out. The Westend synagogue is undeniably one of the most beautiful in Europe, restored to its original splendour a few decades after its partial destruction.

A few hundred metres above the synagogue is the beautiful campus of Goethe University Frankfurt. With its buildings, each dedicated to a faculty, and its long lawns that surround them, it has a light-hearted atmosphere. An American-style campus with a deep German spirit, it is reminiscent of the Ramat Aviv campus and the Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

On Theodor W. Adorno Platz , named in honour of one of the founders of the Frankfurt School, there is a desk, a chair, a lamp and other objects placed on the desk, all under a glass dome. This work by Russian artist Vadim Zakharov was unveiled in 2003 to mark the 100th anniversary of the thinker’s birth.

About 20 yards away is another intriguing work symbolising the open-mindedness and exchange of ideas in the city, and in particular its university: the ‘Body of Knowledge’, created by Spanish artist James Plensa in 2010 and composed of letters from different alphabets.

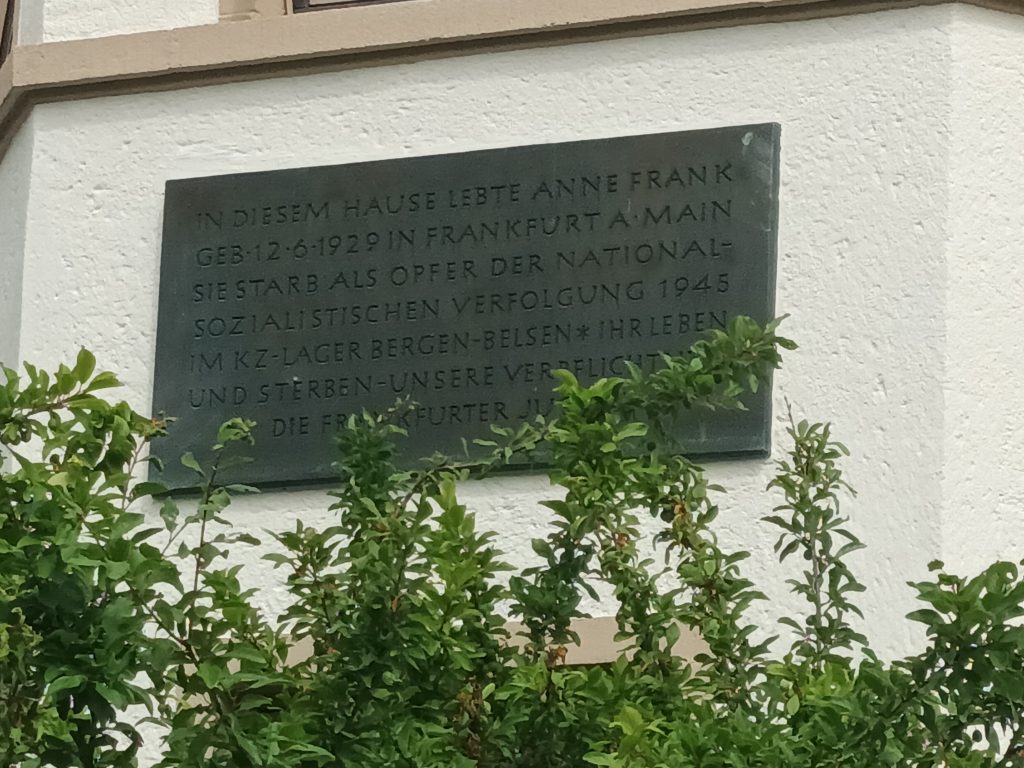

Going back up Theodor W. Adorno Platz and Max Horkheimer Strasse, two kilometres to the north, in the Dornbusch district, is Sinai Park. 300 metres away, on Ganghoferstrasse, you will see the former home of Anne Frank’s family before they moved to Amsterdam in 1934.

Three tram stops separate Goethe University from Anne Frank’s house, which is also a convenient way to return to the city centre.

And who knows, you might find yourself on a tram bearing the colours of Maccabi Frankfurt…