An ancient Roman city, Mainz is known for its university, museums and places of worship, its monuments including the Castle of the Electors, its popular festivals… But Mainz is above all known as the birthplace of Johannes Gutenberg (1400-1468), the man who revolutionised printing.

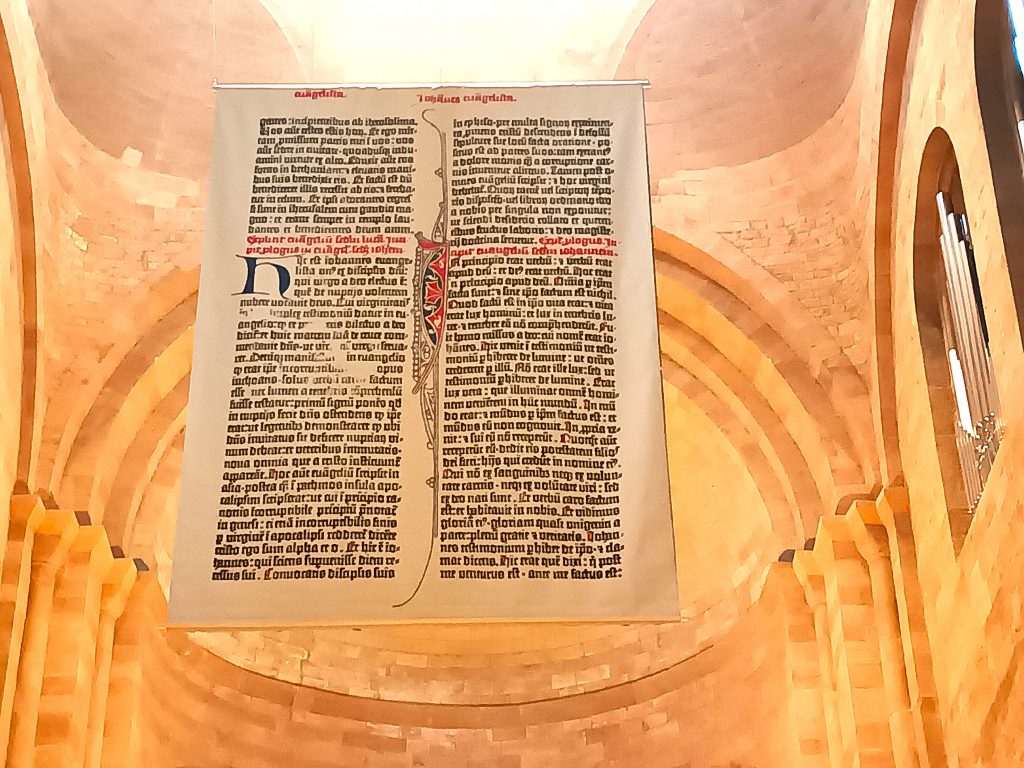

Mainz celebrates Gutenberg’s presence and influence in many different ways, including a museum dedicated to him, statues, squares and, in 2025, the largest pages of the Bible, measuring 5 by 7 metres, hung at the top of the cathedral in honour of the 625th anniversary of Gutenberg’s birth.

ShUM, the famous acronym which, in Hebrew, takes the first letters of three mythical cities: Speyer, Worms and Mainz. Three cities along the Rhine that represent the cradle of Ashkenazi Jewish thought. From the 10th century onwards, and for several centuries thereafter, this region remained one of the centres, if not the largest, of medieval Jewish thought. This was thanks to the great khakhamim who were born, studied and/or taught there.

ShUM means ‘garlic’ in Hebrew. What is certain is that the debates between thinkers of the same generation, and especially later with their disciples, were very varied and very spicy. This curiosity, this requirement inherited from the Bible to end discussions with a question rather than a period or an exclamation mark, encouraged debate, the evolution of thought, its sharing, its generosity… a questioning in the noble sense of the word. It is therefore no coincidence that Rashi, the most famous and respected exegete of the Bible in the Jewish world today, studied in this region.

Mainz probably has the privilege of being the oldest of these Jewish communities. It dates back to the 10th century, if not earlier. Administrative documents confirm the presence of Jews as early as 906. They were expelled from the city in 1012, but were later allowed to resettle there. During the First Crusade, in 1095-1099, more than 1,000 Jews died, either murdered or committing suicide, refusing to convert by force. At that time, there was a synagogue, but it was burned down, along with the Jewish quarter. A few years later, Emperor Henry IV (1050-1106) allowed them to return and live in peace.

As a symbol of this spiritual and intellectual authority, numerous synods were organised in Mainz, notably in 1150, 1223 and 1250. The takanoth of ShUM were respected throughout Europe. Among the great names of this period were the Kalonymus family and, of course, Rabbenu Gershom. Born in Metz in 960, he established numerous yeshivot in both France and Germany. In the year 1000, he convened a synod where important decisions were made, including takanoth that revolutionised Judaism. Among these were the prohibition of polygamy and the requirement that a woman’s consent be obtained in order to initiate divorce proceedings. Rabbenu Gershom died in Mainz in 1028.

In the period that followed, the Jews of Mainz were alternately threatened and protected, depending on the rulers of the time. Thus, during the Second Crusade of 1146-1149, many Jews were murdered, but during the Third Crusade, in 1189-1192, the Jews of Mainz enjoyed the protection of Frederick I (1122-1190), who walked alongside the rabbi to show the population that he would oppose any hostility towards them.

The 13th and 14th centuries were particularly violent for the Jews of Mainz. Forced to wear distinctive signs in 1259, their synagogue was burned down, again, at the end of the 13th century. Following the Black Death of 1349, most of the Jews perished in the flames. Although the end of the 14th century and the 15th century were less bloody, the Jews were subjected to heavy taxation, and their synagogue was converted into a chapel.

Very few Jews still lived in Mainz during the 16th century. It was only at the end of the century that the community regained some strength thanks to the arrival of Jews from Frankfurt, Worms and Hanau. A new synagogue was built in 1639. Their situation worsened during the French occupation from 1644 to 1648. It was only following the influence of Joseph II’s policy of tolerance and the revolutionary spirit in France that their situation improved at the end of the 18th century.

In the 19th century, Judaism in Mainz finally experienced a real renaissance. Although this was not the golden age of the ShUM, great Jewish thinkers and rabbis engaged in very fruitful discussions and even vigorous debates, which gave rise to different currents and schools of thought. The Jewish population of Mainz grew from 1,620 in 1828 to 3,104 in 1900.

At the beginning of the 20th century, this number gradually declined. By 1933, when the Nazis came to power, there were only 2,730 Jews in Mainz. During Kristallnacht, the city’s three main synagogues were burned down. Although nearly half of the Jews managed to flee before the deportations, most of those who remained were murdered during the Holocaust.

After the war, a small community attempted to reorganise itself. There were 80 Jews in 1948, barely more than 100 twenty years later. Most were elderly. As a sign of the changing relationship, Mainz was twinned with the Israeli city of Haifa in 1981.

Thanks to the arrival of Jews from the former Soviet Union, the community was able to rebuild itself, reaching 1,000 members in 2005. A symbol of this revival is the stunning new synagogue , both in terms of its design and architectural achievement, which was inaugurated in 2010.

The Kedusha Synagogue, which also houses a community centre and an exhibition on the history of Jews in Mainz, was designed by architect Manuel Herz.

Its highly complex architectural form evokes the word ‘kedusha’, meaning ‘holiness’.

This Jewish community, which was reborn at the turn of the 21st century, allowed the few Jews still living in Worms to join in religious and festive celebrations.

Near the Gutenberg Museum, a high school has been named in honour of Anne Frank, featuring a Warhol-inspired work with her portrait in several colours.

Stolpersteine (stumbling stones) have also been laid in the city.

The old Jewish cemetery in Mainz , along with the one in Worms, is a very important part of the cultural heritage. This is because they are among the oldest Jewish cemeteries in Europe.

The one in Mainz was used from the 11th century until the 19th century. It consists of several sections, with a new one being built in the 17th century. It was used until 1881, before the opening of the city’s new central cemetery.