The history of the Jews in Speyer dates back more than 1,000 years. In the Middle Ages, the city of Speyer (formerly Spira) was home to one of the largest Jewish communities in the Holy Roman Empire. Its importance is attested to by the frequency of the Ashkenazi Jewish surname Shapiro/Shapira and its variants Szpira/Spiro/Speyer. The community was completely wiped out in 1940 during the Holocaust. With the fall of the Iron Curtain in 1989, Jews resettled in Speyer and a first minyan was held in 1996.

A rich history

The first evidence of a Jewish community in Speyer dates back to the 1070s. It came from the famous Kalonymos family of Mainz, who had emigrated from Italy a century earlier. Other Jews from Mainz may also have settled in Speyer at the same time.

The history of the Speyer community began in 1084, when Jews fleeing pogroms in Mainz and Worms took refuge with their relatives in Speyer. They were certainly encouraged to do so by Bishop Rüdiger Huzmann (1073-1090), who allowed a large number of Jews to live in his city with the consent of Emperor Henry IV. In his charter (Freiheitsbrief) for the Jews, the bishop approved the establishment of the community in a defined area.

This area corresponds to the former suburb of Altspeyer in the area east of today’s railway station. This fortified quarter was located to the north, outside the city walls, and was the city’s first documented ghetto.

The charter ratified by Bishop Huzmann went far beyond the practice elsewhere in the empire. The Jews of Speyer were allowed to engage in all kinds of trade, exchange gold and silver, own land, have their own laws, judicial and administrative systems, employ non-Jews as servants, and were not required to pay customs duties at the city limits.

The two charters

The reason why Jews were called to Speyer by the bishop was their important role in fiduciary and commercial trade, and in particular their links with distant regions. Large-scale financiers were needed for the construction of the cathedral. A special feature of Speyer is that the rights and privileges specially granted to the Jews of this city were eventually extended to all Jews in the empire.

The two charters of 1084 and 1090 marked the beginning of the ‘golden age’ of the Jews in Speyer, which, with restrictions, was to last until the 13th or 14th century. According to these documents, an “Archisynagogos”, also called ‘Jewish bishop’, presided over the administration and the community court. He was elected by the community and ‘knighted’ by the bishop. Later sources mention a ‘Jewish council’ of twelve members, presided over by the ‘Jewish bishop’, who represented the community outside. In 1333 and 1344, the authority of the Jewish council was ratified by the municipal council of Speyer.

In 1096, the Jews of Speyer were among the first to be affected by the pogroms caused by the plague epidemic, but compared to the communities of Worms and Mainz, which followed a few days later, they were relatively spared.

Development of Jewish life

Around this time, a second Jewish quarter was established near the cathedral, along Kleine Pfaffengasse, which was formerly Judengasse (Jewish Street), while the old Jewish quarter and its synagogue remained in Altspeyer. It is estimated that the Jewish community in Speyer at that time consisted of 300 to 400 people.

During these years, the Jewish community in Speyer became one of the largest in the Holy Roman Empire. It was an important centre for Torah study and, despite pogroms, persecution and expulsions, had a considerable influence on the general spiritual and cultural life of the city. At a synod of rabbis in Troyes around 1150, the leadership of the German Jewish community was transferred to the communities of Speyer, Worms and Mainz.

Intellectual and religious development

The three communities formed a federation called ‘ShUM’ (שום: initials of the Hebrew names of the three cities) and retained this power until the middle of the 13th century. The SHUM cities had their own rites and were recognised as a central authority in legal and religious matters. Speyer had renowned Jewish schools and a well-attended yeshiva.

Due to the high esteem in which the three ShUM cities were held in the Middle Ages, they were praised as a ‘Rhenish Jerusalem’. These cities had a considerable influence on the development of European Ashkenazi culture. In the 13th century, Isaac ben Moses Or Sarua of Vienna wrote: ‘From our teachers in Mainz, Worms and Speyer, the teachings have spread to all of Israel …’.

However, even during this flourishing period, anti-Semitic violence broke out in 1146, 1195, 1282 and 1343. In 1349, during the Black Death, the Jewish community of Speyer was completely wiped out. In the years that followed, a small community re-established itself, but never regained the size and status it had before 1349. The Jews were expelled from Speyer from 1405 to 1421, then ‘for eternity’ in 1435. One of the refugees from Speyer was Moses Mentzlav, whose son, Israel Nathan, founded the famous Hebrew printing press in Soncino, Italy.

Return of the Jews to Speyer

From 1621 to 1688, Jews resettled in Speyer. It was mainly during the Thirty Years’ War and the years that followed that the indebted towns called on the financial power of the community. The city began borrowing money from Jews as early as 1629. However, following complaints, trade and financial transactions with Jews were completely banned before Speyer was burned down by the French in 1689. During the subsequent years of reconstruction, Jews were not allowed to resettle permanently.

A Jewish community established itself in Speyer after the French Revolution. It was distinguished by its liberal and emancipated attitudes, which repeatedly brought it into conflict with the more conservative Jewish communities in the Rhine region. In 1828, the community founded a charitable organisation and contributed to the city council’s efforts to combat extreme poverty in the city. In 1830, the Jewish community in Speyer had 209 members. In 1837, a new synagogue was built on the site of the former St. James Church on Heydenreichstraße; the synagogue included a small school.

Rise of anti-Semitism

In 1890, the Jewish community had 535 members, the largest number ever recorded in Speyer; by 1910, their number had fallen to 403. In the early 1930s, Jews in Speyer began to leave for larger cities or emigrate due to rising anti-Semitism.

By 1933, the number of Jews in Speyer had fallen to 269, and by the time their synagogue was burned down during Kristallnacht, only 81 remained. On the night of 9 November, SA and SS troops ransacked the synagogue on Heydenreichstraße, carrying off the library, valuable fabrics, carpets and ritual utensils, and set fire to the building. Along with the synagogue, the Jews also lost their school. That same night, the Jewish cemetery was vandalised. A member of the community set up a prayer room in his house on Herdstraße. The city then used this house as a storage place for furniture stolen from deported Jews.

On 22 October 1940, 51 of the 60 Jews remaining in Speyer were deported to the Gurs internment camp in southern France.

Some of them managed to flee to Switzerland, the United States and South Africa with the help of the local population, while the others were deported to Auschwitz. Hidden in Speyer, only one Jew survived the Nazi era.

In the 1990s, it was decided to build a new synagogue as an extension of the former medieval church of St. Guido. The Beith Shalom Synagogue was consecrated on 9 November 2011. It also houses a community centre.

The medieval Jewish cemetery of Speyer lay opposite the Judenturm (Jews’ tower) to the west of the former Jews’ quarter in Altspeyer (today between Bahnhofstraße and Wormer Landstraße).

After Jews resettled in Speyer in the 19th century, a new cemetery was built at St. Klara Klosterweg and remained in use until 1888. The former mortuary and a part of the western wall are still in place. In 1888, the Jewish cemetery was moved to the new city cemetery built in the north of Speyer along Wormser Landstraße, where it now occupies the southeastern section.

How to get there

When you leave Speyer railway station on Banhoferstrasse, you will find yourself in Adenauer Park. Named in honour of former German Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, it is the site of the grave of another former chancellor, Helmut Kohl.

After crossing this pretty little park, you will come to St.-Guido-Stiffts Platz. Don’t be surprised to find a sign in two languages, German on one side and Hebrew on the other, indicating the location of the Kikar Yavne . This square is named in honour of the Israeli city of Yavne, with which Speyer has been twinned since 1998.

Take the small alleyway called Weidenberg and you will come to a pretty little park full of flowers, where you will see a metal menorah sculpture and, just behind it, Speyer’s Beit Shalom synagogue .

Next, walk down Wormser Strasse and the adjacent narrow streets with their colourful houses and lush vegetation to reach the heart of the old town. Stolpersteine have been placed opposite number 9 on the street.

At the end of this street is the unmissable Maximilian Strasse. On the right, you can see one of the city’s most famous monuments, the Altpörtel, a 55-metre-high medieval gate built in the 13th century.

Maximilian Strasse is the main shopping street in the old town. It connects the main ancient monuments from the Altpörtel to Speyer Cathedral. Opposite the beginning of Wormser Strasse, 50 metres from the Altpörtel, is the Galeria Speyer, a large department store located on the site of the synagogue destroyed during Kristallnacht .

If you take the Karlsgasse alleyway that runs alongside the store, you will find the Memorial erected in 1992 in honour of the Jews of Speyer who were deported during the Holocaust.

Then turn left onto Hellergasse, which continues into Kutschergasse, and you will arrive at the small market square. Crossing it diagonally, you will come to Kleine Pfaffengasse , where the Jewish Museum of Speyer, the SchPIRA and its mikveh , is located.

Just before the museum, on your right, you will see Judengasse and Judenbadgasse, named after the Jewish alley and the Jewish ritual bath, respectively.

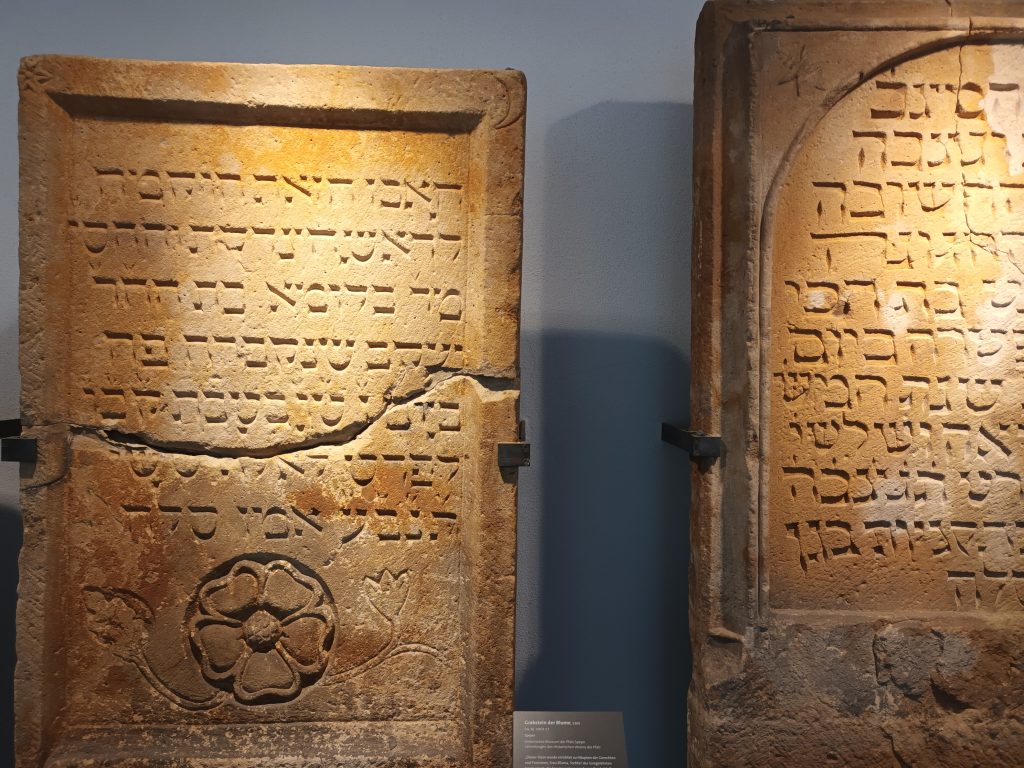

The SchPIRA is relatively small. It contains a few ancient objects, remnants of the old synagogue and gravestones, which appear to date from the 13th century.

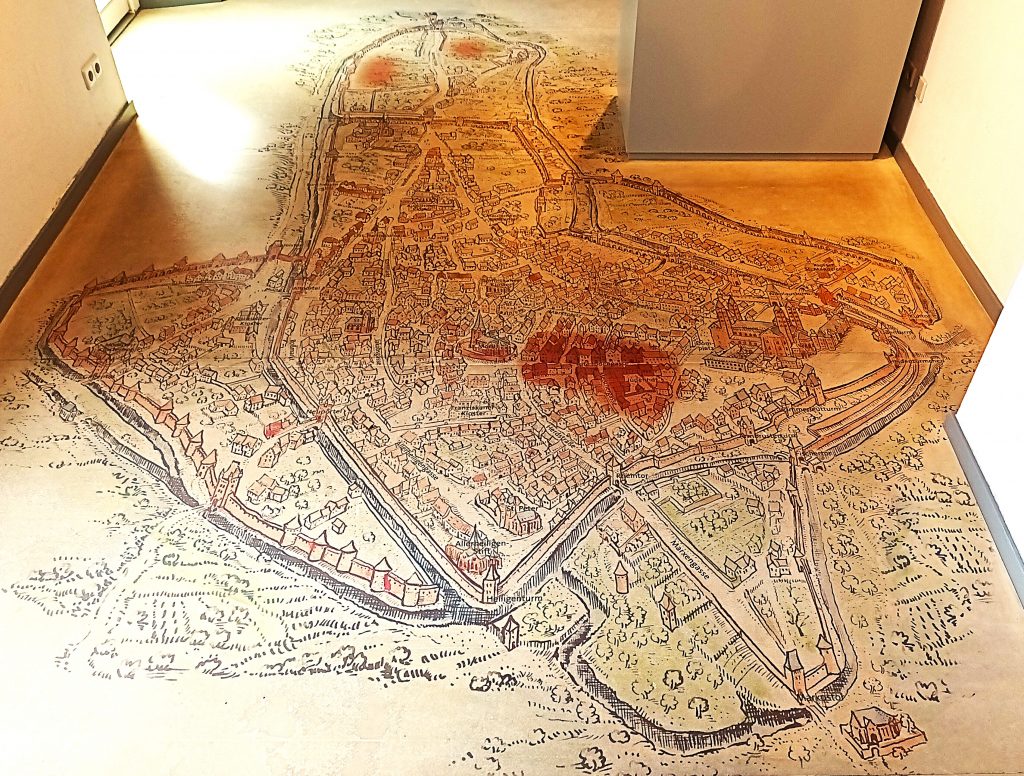

A model of the old mikveh is on display so that visitors can see what it looked like as a whole. On the floor is a map of ancient Speyer.

In the next room, a few panels trace the history. Seats allow you to watch presentation videos in German or English at your leisure. Two films are available in English. The first lasts 12 minutes and tells the story of the synagogue, its evolution over time and the necessary (re)constructions. A particularly interesting element in this presentation is the construction of the women’s hall. In some synagogues at the time, women were not just seated behind or above the men, but had their own room. A few windows connected this room to the men’s room so that the women could follow the prayers.

The video shows the architectural evolution of the synagogue and the influential role played by this community at the end of the Middle Ages. It also mentions its destruction, following classic anti-Semitic accusations of poisoning wells, as was the case throughout medieval Europe. The other video is devoted to Jewish rituals, with a view to explaining their meaning to visitors.

In the museum’s small flower-filled garden, you will see a few sculptures, including one entitled ‘The Sages of Speyer’, in memory of all the eminent rabbis who trained and taught there.

Opposite the small inner garden, on the right, you can see the remains of the synagogue with its two rooms. Red and yellow stones bear witness to the architectural evolution of synagogues over time. Some windows connecting the men’s room to the women’s room are still intact. These windows, actually six small openings, were cut into the wall between the two rooms. There was also a connecting door between them, located at the western end of the wall. Benches were positioned around the women’s prayer room. One of them is still preserved today.

The synagogue, consecrated in 1104, was built as a Romanesque room approximately 10 metres wide and 17 metres long. The place of worship was damaged during the pogrom of 1349 and repaired in 1354 with several modifications to its construction. After the expulsion of the Jews in the early 16th century, the synagogue was converted into a municipal arsenal before finally being demolished.

The first architect to work on the synagogue was not Jewish, as Jews were prohibited from practising certain trades at that time, particularly those related to craftsmanship. In 2025, restoration work was carried out on this former synagogue.

Right next to the remains of the synagogue is the famous Speyer mikveh. The ritual bath fell into disuse in the 16th century, but its ruins are now the oldest visible remains of a mikveh in Central Europe. Today, this European archaeological heritage site has been made accessible to the public and the pool is still fed by groundwater. The first mention of the mikveh dates back to 1128. It was therefore probably built at the same time as the synagogue, at the beginning of the 12th century. It is very well preserved and lit, allowing you to descend to the place where the ritual bath was located, where water still flows abundantly.

The Speyer mikveh is considered today to be the best preserved in Europe. A barrel-vaulted staircase leads through a vestibule to a square well located 10 metres below ground level. The mikveh is decorated with rich colourful ornamentation from the Romanesque period. A two-part window opens up a view of the basin. The mikveh is now covered with a glass structure to protect it. The bath is no longer officially in use today, but its use can be arranged outside official opening hours for tourists.

All around are explanatory panels about the construction of the mikveh, as well as the chronology of Jewish life and the heyday of the Speyer community, and its contemporary revival.

Leaving the SchPIRA museum, turn right onto Kleine Pfaffengasse and continue for 100 metres to Domplatz, where you will find the beautiful and immense Speyer Cathedral, built from the 11th century onwards under Conrad II.

At the entrance, you can see famous scenes from the Bible carved in wrought iron. Inside, as in many German cathedrals, beautiful organs are sometimes played to the delight of visitors. Paintings and statues inside and outside the cathedral pay tribute to the Bible and German rulers.

To round off your walk, we recommend the lovely park just behind the cathedral, where you can see contemporary sculptures and enjoy the peaceful greenery.