Bologna is famous for having been one of Europe’s leading cities in the Middle Ages. Thanks to its large population living within its walls, the wealth of local agriculture, the development of trade with the other cities of Emilia-Romagna, but also and perhaps above all to the dynamism provided by its university, the oldest in Europe.

History of the Jews of Bologna

The first traces of a Jewish presence in Bologna date back to 1353, when a document mentions a certain Gaio Finzi, “judeus de Roma”. Jews from the surrounding towns of Fabriano, Pesaro, Orvieto and Rimini also settled here in the second half of the 14th century.

The Italian rabbis met in Bologna in 1416 to agree on a petition submitted to Pope Martin V. In 1468, a professor of Hebrew was recruited by the University of Bologna. Between 1477 and 1482, a number of Jewish publishing houses were established, remaining active until the middle of the 16th century.

Following the Spanish Inquisition in 1492, Sephardic Jews settled in Bologna, including Rabbi Jacob Mantinus. Ovadyah Sforno, a doctor and rabbi, founded a renowned Talmudic school in 1527. In 1553, following a counter-reformation campaign, Talmud and other Jewish books were publicly burnt.

Two years later, Pope Paul IV forced the Jews to live in ghettos in all the cities of the Papal States. The one in Bologna was created in 1556 and closed by two gates. In 1569, the Jews of Bologna were expelled from the city. Pope Sixtus V authorised their resettlement in 1586. But they were expelled again seven years later.

It was not until 1796, with Napoleon’s conquest, that the Jews of Bologna were allowed to return and, above all, to worship freely, as was the case in France following the emancipation of the 1789 Revolution.

As a sign of its official recognition, the Jewish community was given access to an oratory in 1829. Following the loss of power by the Church and the proclamation of the Roman Republic, all Italian Jews were officially declared free in 1860. Nine years later, a plot of land in Bologna’s municipal cemetery was granted to them. The Bologna synagogue, built by the architect Guido Lisi, was inaugurated in 1877.

Following the promulgation of the “racial laws” in 1938 by Mussolini’s regime, Jewish teachers and students were excluded from schools and universities. The deportations of Bologna’s Jews began in November 1943. This was the case for 85 of them, including Rabbi Alberto Orvieto. Following the Holocaust, the Jewish community was rebuilt and by 2024 had grown to almost 300 members.

Tour of Bologna

We invite you to follow an itinerary through this sumptuous city, with its red buildings and temper by day and subtle yellow lighting at night.

The train takes 7 minutes from the airport to the station. As soon as you get off, you notice the arcades.

Arcades from different eras, in different styles, everywhere, overhanging the streets. A policy of building expansion put in place in response to the problems of overcrowding in this city, which was already one of the five largest in Europe in the Middle Ages. A desire to build forwards rather than upwards. Perhaps also a way of protecting and accompanying passers-by.

To the right of the station, you’ll find working-class neighbourhoods, as well as MAMBO, the Museum of Modern Art, a multi-disciplinary cultural complex that houses a film school with a lovely graffiti tribute to Agnès Varda at the entrance. Also in the area, the park named in tribute to 9/11 and the monument in Place Lamé, with its sculptures in memory of the partisans.

Take the main boulevard Via Giovanni Amendola, which runs from the station to Piazza dei Martiri 1943-1945 and then becomes Via Guglielmo Marconi, which leads directly to the Bologna synagogue by turning left into Porta Nova.

The contemporary synagogue is on Via Finzi, at the western entrance to the old quarter. A small oratory was founded by Angelo Carpi in his house in 1829. In 1868, the growing community rented a room in a building on Via Gombruti. Between 1874 and 1877, a larger synagogue was built in the same building. The synagogue was destroyed in an air raid in 1943 and rebuilt in 1953.

The main hall is now used only for major festivals. In 2017, a small synagogue was built underneath the building. During the works, a Roman mosaic and other magnificent ancient works were discovered. In order to preserve and allow visitors to see them, the floor of the synagogue was constructed in the form of a grid. The community may be small, but it remains fairly dynamic and enthusiastically welcomes visitors Shabbath. “Naturally”, for security reasons, visitors must apply by e-mail. The synagogue was the victim of an anti-Semitic attack in January 2025, causing damage.

We then take the Porta Nova, which leads to the Via IV Novembre, to bringing us closer to the heart of the old town. Continuing in a straight line, you arrive at the famous Piazza Maggiore and Piazza del Nettuno (with its statue of the god of the seas), home to the sumptuous buildings of the Town Hall (the Palazzio d’Accursio) and the Basilica, built in two stages as you can see from the outside.

These squares are very busy both day and night, with a mix of impromptu concerts, terraces, students, commuters and tourists.

The Palazzio d’Accursio welcomes on its outside wall facing the Piazza del Nettuno a tribute to the Partisans who died to liberate Bologna during the Second World War. Head towards the Medieval Civic Museum along Via dell’Independenza, passing the imposing San Pietro cathedral and its beautiful, endless arcades and designer shops.

Turn left onto Via Manzoni to reach the Medieval Civic Museum , an important stop-off point for discovering the history of Bologna and the greatness of the city in those days. As you enter the museum, you come across a wooden candlestick that closely resembles a menorah.

Between the various rooms of this labyrinthine museum, three ancient Jewish tombstones and a Muslim tombstone are displayed side by side in two courtyards.

Behind the second courtyard is the Lippo di Dalmasio, dedicated to works from the Trecento and Quattrocento periods. Works from the period are on display, and the economic links between Bologna and Pistoia, which led to their mutual development during this golden age, are also explored.

The tour continues in other rooms, featuring Gothic frescoes of professors surrounded by students in this city of learning. Then there are small statues that were very popular in the Renaissance, huge books combining texts and ancient graphics, and knights’ outfits.

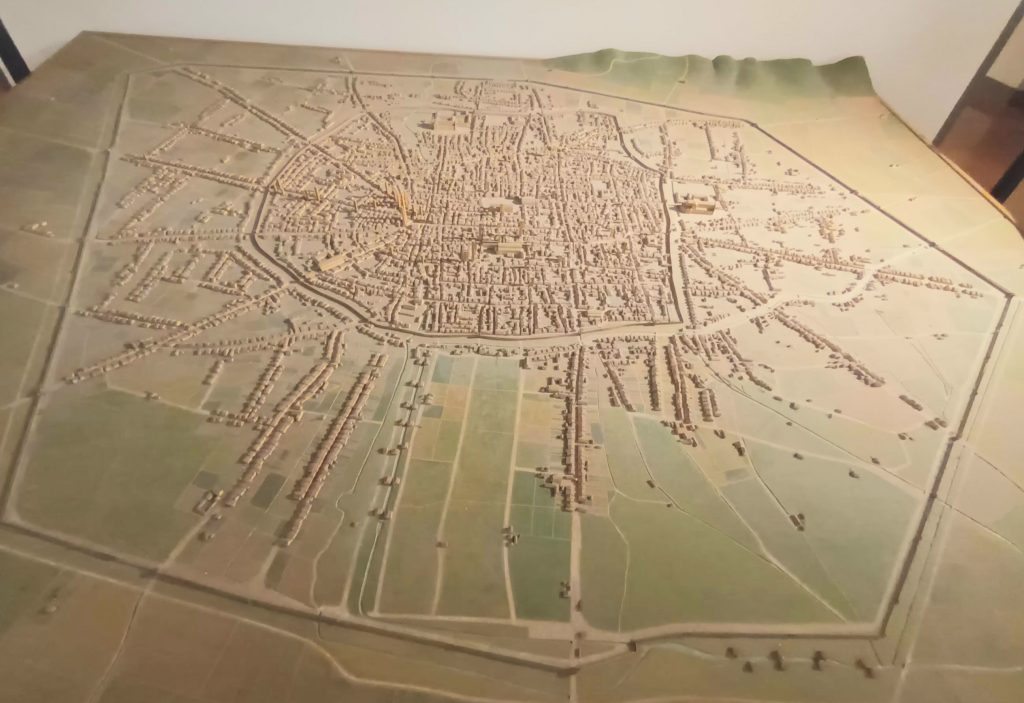

Above all, there is a beautiful model of the town in medieval times, which in the 13th century had a population of 50,000, one of the highest in Europe at the time.

On leaving the museum, head north along Via dell’Independenza and take the first street on the right. Located in Via Goito, Palazzo Bocchi was built in 1545 and 1565 by Jacopo Barozzi and Sebastiano Serlio.

It is a typical example of Renaissance architecture. The scholar Achille Bocchi founded his Literary Academy here. He had two inscriptions placed on the façade. One is in Hebrew, taken from Psalm 120: “O Lord, deliver my soul from the lying lip, from the deceitful tongue”; the other is in Latin, taken from an epistle by Horace: “Behave well and you will be king, they say”.

Continuing along Via Goito, you come to Via Guglielmo Oberdan. This is one of the two historic entrances to the ghetto. On Via Oberdan, turn into Vicolo Tibertini. Here you can see a map showing where the Jews of Bologna used to live. The old Via del Ghetto has been renamed Vicolo Mandria.

The synagogue was located on Via dell’Inferno. Entering this street, you come to Via Canonica, then Via de’ Giudei (the street of the Hebrews) and Via del Carro.

At the end of the street, you come to the famous towers of Bologna, built in the 12th and 13th centuries. The Asinelli Tower is 97.2 m high and the Garisenda Tower is only 48 m high, but it was this tower that inspired Dante. It was shortened because it was in danger of collapsing.

If you go up Via Zamboni, back into Via del Carro and then Via Valdonica, you will come to the Museo Ebraico di Bologna .

This Jewish museum is housed in Palazzo Pannolini, which in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries was the home of the Pannolini family, producers and merchants of woollen cloth.

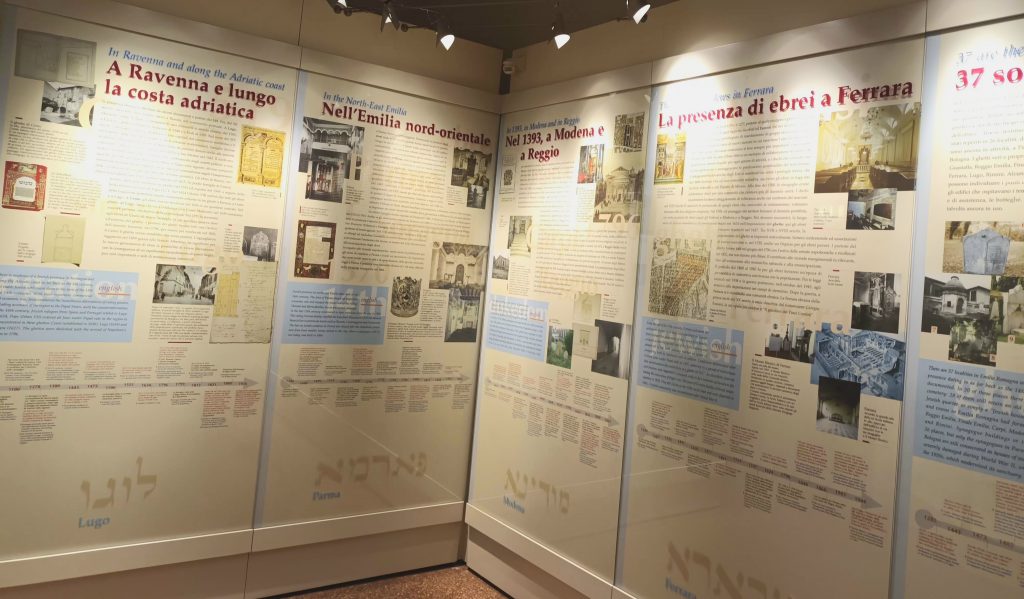

Inaugurated in 1999, this avant-garde museum is divided into two halls. One is devoted to the permanent exhibition and the other to temporary exhibitions. The permanent room begins with a general presentation of Judaism, the different customs, communities and their evolution over time.

The age of the Italian communities is highlighted, as is their fluctuating welcome, which has varied according to the political and religious leaders of the different eras since Antiquity. A sign indicates that Jews were present in 37 towns and villages. The tour covers both ancient and contemporary history.

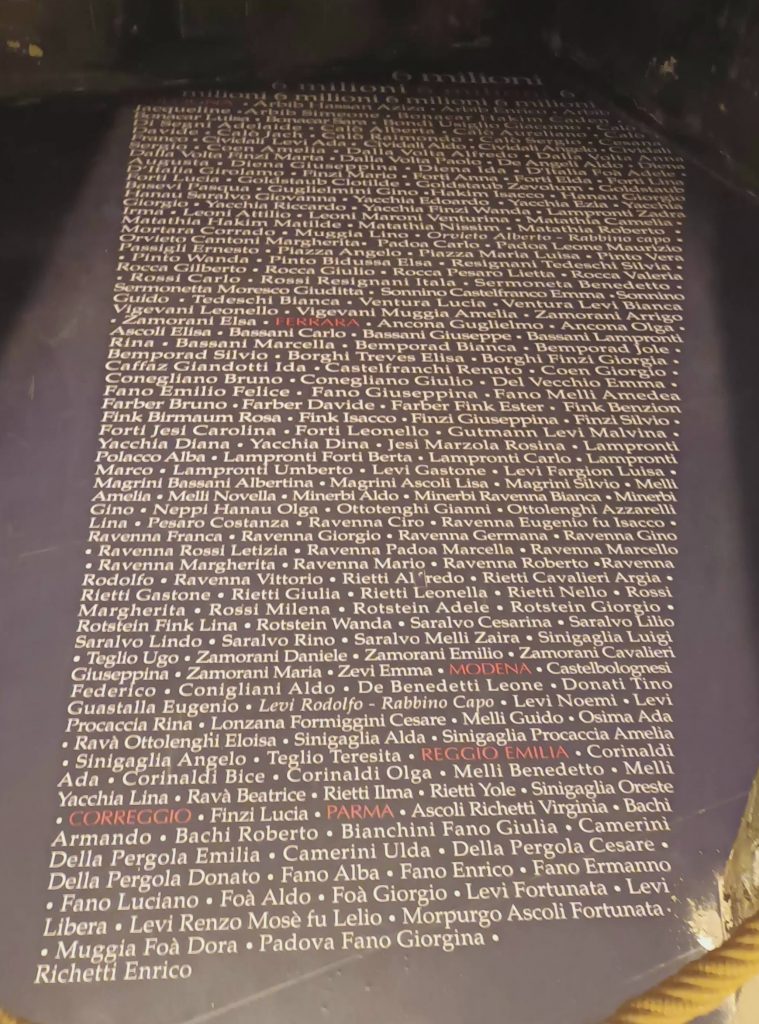

A small room is also reserved for a monument in memory of those deported from the region to the concentration camps.

Crossing the Place Verdi, the municipal theatre and the conservatoire with its large restaurant where many students meet, you arrive at the University of Bologna .

Founded in 1088, it is the oldest university in Europe! It forms a large complex, divided into study departments: physics, natural sciences, humanities, law, literature, etc.

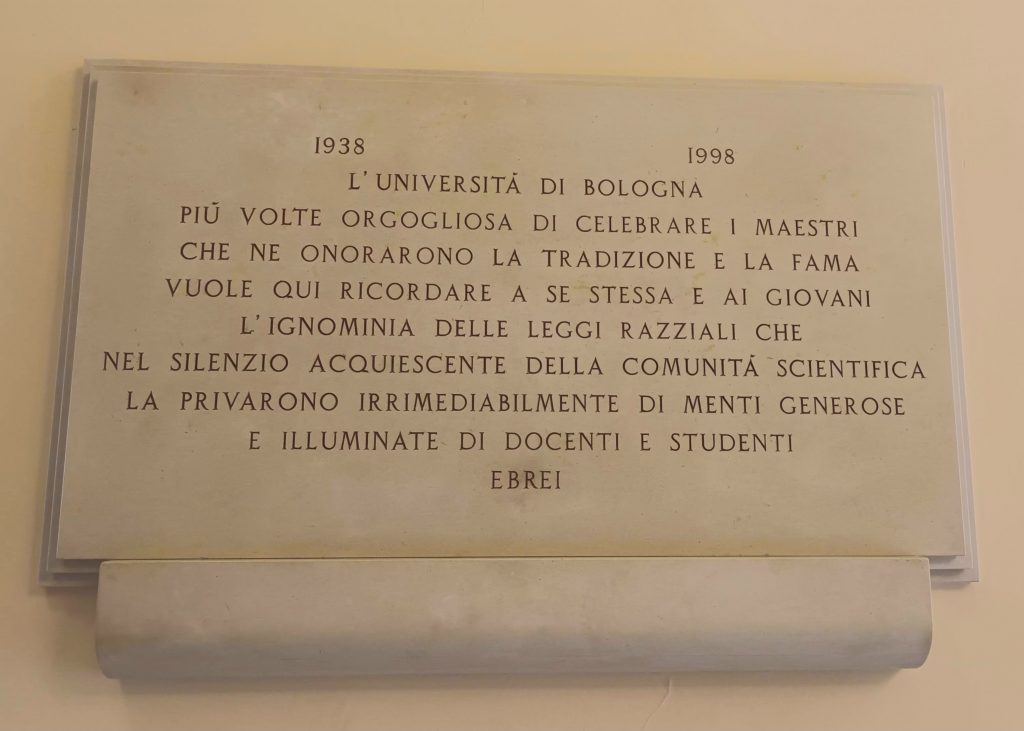

At the entrance to the university which leads to the museum, there is a plaque in memory of the Jewish students who were subjected to racial discrimination in 1938 under the Mussolini regime.

As you enter the museum on the left, you pass through various rooms celebrating scientific discoveries and all the courageous people who made these discoveries possible and supported them during political and religious struggles, encouraging encounters and curiosity. The result, of course, was the development of the university that accompanied Bologna’s status as one of the main European cities of the Middle Ages.

As you enter the museum on the right, you will see a room dedicated to military strategy, with plans of fortresses, warships and ancient cannons. Then there is an introductory science room for children. Next to this, in 2024, was a display of 20th century Japanese art.

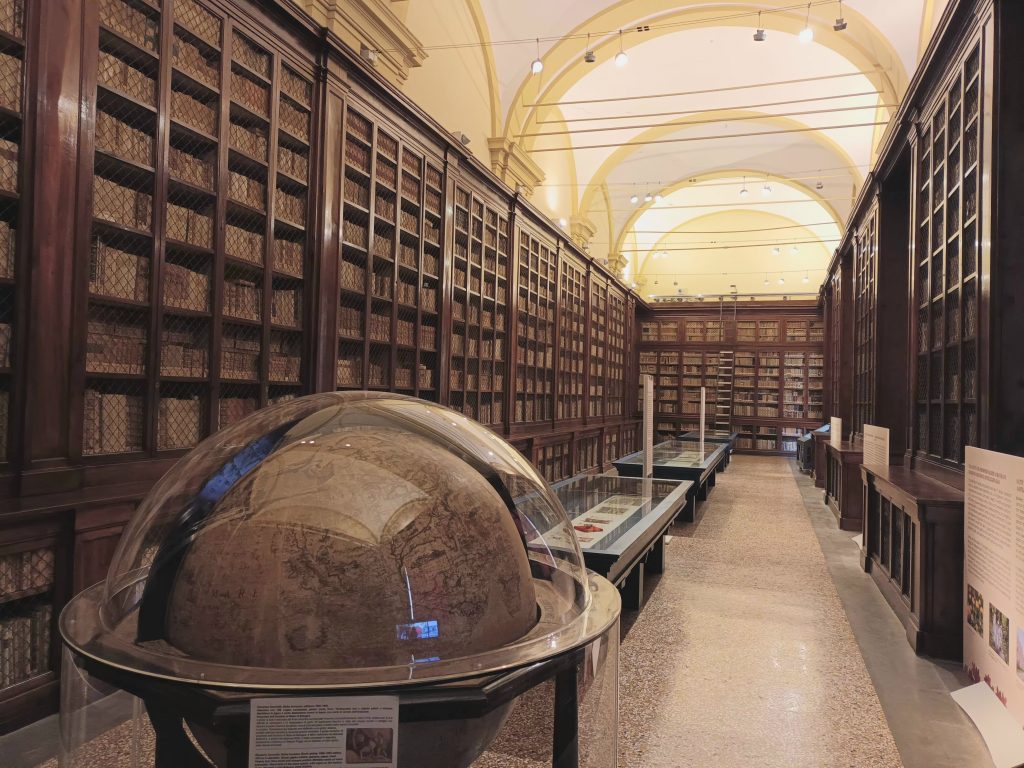

The exhibition ends with the very impressive old university library. Next to the new library is a bust of a former student, a certain Dante!

Leaving the university, head towards Via Irnerio to arrive in Piazza dell’8 Agosto, home to a large market. To the right of this is the Parco della Montagnola. This is a garden with astonishing statues and frescoes depicting battles between animals and mythological beings, as well as historical battles. These works surround the fountain, and the many children who play there after school.

At the top left of the garden, you’ll see the Porta Galliera. Below it and to the side, ancient ruins. The railway station is just opposite. Behind it, outside the city walls, is the Shoah Memorial .

Inaugurated on 27 January 2016, it stands at the junction of Via dé Carracci and Via Giacomo Matteotti. Two steel rectangles face each other. Between them is a corridor that begins 1.60 metres wide and narrows to 80 cm, creating a feeling of oppression. The interior of the parallelepipeds is reminiscent of the dormitories at Auschwitz. The floor is made of ballast, like the stones made by Auschwitz I and II prisoners. Finally, the choice of steel, a material that rusts and deteriorates over time, is deliberate.