The former ghetto of Florence was located in the heart of the old city center near the market in a zone totally destroyed and the end of the twentieth century, situated today between Via Brunelleschi, the Piazza della Repubblica, and Via Roma. Bernardo Buontalento, the grand duke’s architect, was commissioned to design the ghetto. The streets accessing the residential blocks were walled, with the exception of two gates that were closed each evening.

As in Siena, in Florence Jews from all the villages and towns of Tuscany were confined inside a labyrinth of alleys and courtyards. The Jews were excluded from guilds, and hawking used clothing was the only occupation open to them. They remained in the ghetto a=for almost three centuries, until 1848. Its two synagogues, one with Italian services and the other with Spanish, were destroyed at the same time as the ghetto at the end of the twentieth century. Shortly before the opening of the Grand Temple, two small oratories were created in 1882. In use until 1962, one oratory held services in Italian; the other followed an Ashkenazic liturgy. Both of them are commemorated in a plaque on the building at 4 Via delle Oche, which was the offices of the Mattir Assurim confraternity.

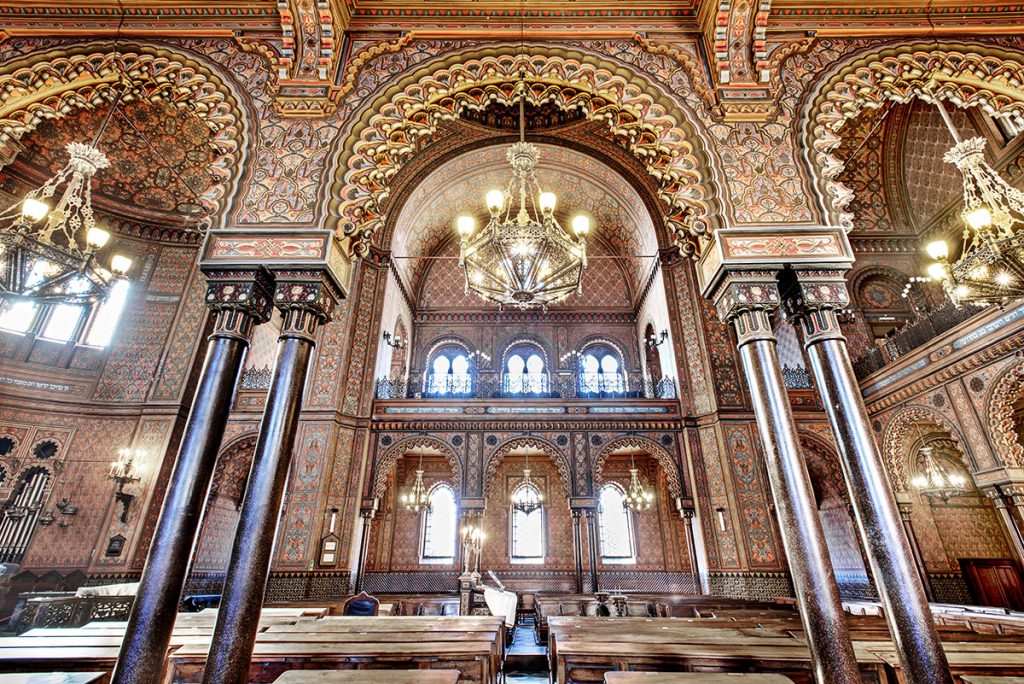

The imposing neo-Moorish Grand Temple (Tiempo Maggiore) was unveiled in 1882 after eight years of construction. Designed by Marco Treves with the assistance of architects Mariano Falcini and Vincenzo Micheli, this synagogue with its majestic pink and white stone facade is dominated by a large green dome and two matching minarets on each side. The Tablets of the Law crown the pediment. The rich Moorish-style interior is sumptuously decorated with arcades of slender columns, and in the center, there is a semi-circular apse where the aron and the bimah are enthroned, separated from the rest of the prayer hall by a finely wrought grille. The mosaics and frescoes of gold and azure are the work of Giovanni Panti. During the war, the Nazis used the temple as a military garage and attempted to dynamite it during their retreat, fortunately without substantial damage. Carefully restored, the synagogue was later victim to the great flooding of the Arno River in 1966, which filled it with seven feet of water. A large portion of the 15,000-volume library was severely damaged.

The facade of the Basilica Santa Croce

The facade of the Basilica Santa Croce is decorated with a large Star of David that will probably arouse your curiosity. In their Guida all’Italia Ebraica (Guide to Jewish Italy), Annie Sacerdoti and Luca Fiorentino tell of its strange origin: “In 1860, it was decided to renovate the church’s thirteenth-century Gothic facade with polychrome marble. The work was entrusted to the architect Nicolò Matas, a Jew from Ancona who incorporated the large star as an element of the decoration. No one paid any attention to the architect’s Jewish origins, even after he specified in his contract that he would not work on Saturdays. When he died, he put the Jewish community and the Franciscans in a difficult position by stating in his will his wish to be buried in the basilica. A compromise was finally reached: he was interred in a marble sarcophagus just outside the church under the flight of stairs facing the main entrance.

Opened in 1981, the Jewish Museum is on the second floor in a vast room divided into two parts: one houses a collection of photos, visual witnesses to Jewish life in Florence, and the other contains beautiful religious objects, especially silver pieces and textiles. You can also admire a beautiful old rimmon dating from the end of the sixteenth century. At the museum exit, a large plaque commemorates the 248 Jews from Florence who were deported and died in the death camps or were executed.

Interview with Emanuele Viterbo, Head of the Jewish Community of Florence

Jguideeurope: How was the Jewish Museum of Florence created?

Emanuele Viterbo: The design of the Jewish Museum in Florence, strongly backed by Rabbi Fernando Belgrado, was initiated in 1981as a result of the donation of Marta del Mar Bigiavi. The first exhibit occupied the first floor in a room behind the women’s gallery and included the historical section and the furniture and home furnishings of synagogue worship. The project was designed by the architect Alberto Boralevi, with the exhibition design by Dora Smooth. The second part of the museum, opened in 2007, is located on the top floor, and was designed by the architect Renzo Funaro in collaboration with the architect Michael Tarroni and was set up by Dora Smooth and for the textile industry section by Laura Zaccagnini.

This time, the museum was divided into two sections: the first floor were the furnishings ceremonial use in the synagogue, in the latter have been moved to objects for domestic worship. One room, curated by Renzo Funaro and Liana Funaro, was dedicated to the Holocaust.

The choice of rooms and Museum set up has been done based on museological and conservation considerations. First, it was decided to set it in the Temple which, due to its artistic and historical importance for its monumentality, not only represents the ideal, but it has become an integral part of the course of Jewish History in Florence. The cellars, while beautiful and impressive, but who did not have security policies because of the danger of floods (the last of which, in 1966, came up to two meters in height above the height difference created by the steps outside), have been discarded. It is a relatively small museum, but very impressive.

The collections of the Jewish Museum in Florence are arranged on two floors inside the synagogue.

The first section documents the history of the Jews in Florence over the centuries and their relationship with the city. In the display cases are furniture, textile, and silver, used for ceremonies synagogue between the end of the sixteenth and nineteenth centuries. On the second floor, in a room with a beautiful view on the inside of the temple, there are objects and furnishings of domestic and private devotion, illustrating the highlights of the festivities and religious life of a Jew such as birth, marriage and religious ceremonies. Many of these items are gifts from Jewish families who wanted to testify so their attachment to the Community. Important figures in the community in the knight David Levi, who left his fortune to construct the building of the synagogue, and that of Rabbi Shmuel Zvi Margulies, of Polish origin, who renewed the Italian Rabbinical College and brought it to Florence.

The tour continues with a film that introduces the history of the community in the past two centuries, and a room of Remembrance, where photos and archival records of the life of the Jews in Florence, the newfound equality after the age of ghettos, persecution, to following the racial laws, and deportation to the death camps, to the rebirth and reconstruction after the war, are displayed. A computer room connected to the major Jewish museums in the world and puts the Florentine Jewish life in a very broad context.

The museum consists of a first section, which documents the history of the Jewish Florentine by birth, in 1437, at the time of the founding of the Ghetto, its extension in 1571, and again from 1704 to 1721, until the demolition of the last decade the nineteenth century. This is illustrated through photographs of plants, pictures of the ghetto destroyed and ancient synagogues. Newer images illustrate the story of the design and construction of the Temple. There is also a nod to the other sites of Jewish Florence.

Most of the furnishings are from two synagogues in the Ghetto, that the Italians opened after the creation of the district intended to house arrest by the Jews in 1571, and the Spanish and Levantine, opened a few years later, which objects were added that belonged to the synagogues of Arezzo and Lippiano -communities that are now extinct- and by the synagogue, for which they were specially made. Considerable space is devoted to the ornaments of the Sefer Torah, the scrolls of parchment on which the Hebrew bible is written.

The second part of the museum, opened on the top floor in 2007, is a collection of objects and drawings that summarize the origins of the Jewish community in Florence.

If the Chevalier David Levi is the symbol for excellence of Italian Jewry (illustrated in “the Italian,” a beautiful portrait by Antonio Ciseri in 1854), the core of most influential Jews were of Sephardic origin, originating in Spain, subsequently, the countries of North Africa and the Middle East. Here you can view significant objects that illustrate the most important moments of life and religious holidays, with personal or household furnishings organized by type and according to different occasions. The family has a very important role in the Jewish religion.

Most of the six hundred commandments (mitzvot), that every jew is obliged to follow, are put into practice in daily life. Many of the exhibits in the museum follows the story of an important Florentine family, the Ambron-Errera family, whose history can be witnessed here.

Tempio Maggiore is considered one of the most beautiful synagogues of Europe. How was its style imagined?

The synagogue of Florence was inaugurated in 1882, not longer after the emancipation of the Italian Jews which was proclaimed in 1861 when the Kingdom of Italy was established. The Florence synagogue is one of Europe’s finest examples of a blend of the exotic Moorish style with Arabic and Byzantine elements that characterize the white travertine and pink limestone façade, the copper-cladding on the central and lateral domes (originally they were gilded), and the massive walnut doors. The style is also reflected in the interior decorations and furnishings. The community had been debating about a new synagogue since 1847, but the lack of funds made it impossible to take any concrete steps. Then, in 1868, Cavalier David Levi bequeathed the money for the construction of a “Monumental Temple worthy of Florence”. Two years later, in 1870, three architects, Mariano Falcini, Marco Treves and Vincenco Micheli, were appointed to design the temple.

The location was finally selected after lengthy discussions between the factions that wanted it in the city centre and the group that preferred a site outside. The latter prevailed, and the choice fell on the “Mattonaia” district which, though still within the city walls, was not completely developed, indeed there were still many parks and gardens. The new Temple was opened on 24 October 1882.

Two seemingly opposite, but actually related approaches influenced the design. On the one hand there was the influence of Christian churches and the Old Spanish synagogues, and on the other was desire to express Jewish identity through a distinctive architectural style. The final result, the “child” of nineteenth century Eclecticism, was something new that combined Moorish, Byzantine and Romanesque elements.

How did the Resistance save the Tempio Maggiore from destruction during the war?

In 1938 the Fascist regime enacted racial laws which deprived Jews of work and schooling, among other restrictions and dubbed them an inferior race. In September 1943, the Nazis effectively seized control of a large part of the country. Some Jews saved themselves by fleeing abroad while others went into hiding and were sheltered by the local population. In total, 9,000 Italian Jews were deported or killed, more than 500 of them were from Florence. After the war, the Jewish school was reopened and the Synagogue was renovated.