When we think of Stockholm, we often envision the Viking past. Certainly, they are part of the history of the city, the country and the region. There’s even a Viking museum in Stockholm. But this city offers much more. For a start, its name means “a multitude of islets”: Stock (multitude) and holm (islet). And it’s on these 2 small central islets that you can start travelling back in time.

From Stockholm’s Royal Palace on Gamla Stan (“Old Town”) to the Museum of Modern Art and the Design Museum on Skeppsholmen. This style has and continues to influence our contemporary world, from buildings and department stores to ready-to-build furniture.

Not sure you’ll have time to visit all 24,000 islands. But a boat trip will let you discover a sample of them, whether by public transport or with the companies that organize such trips. So many different monuments await you. Whether it’s the beautiful cathedral, the Nobel Prize Museum, the Vasa Museum with its impressive 17th-century royal ship, the Nordic Museum… or the many green spaces, testimony to the care for the environment both on land and at sea.

There’s also a wide range of lifestyles, between the dark and cold of the North during the winter days, and the desire for colorful night-time celebrations. As can be seen in the stylistic distance between the highly calculated changing of the guard at the Royal Palace (a famous tourist attraction) and the Abba Museum, which takes us back to the atmosphere of the carefree years.

Not forgetting, of course, the city’s culinary specialties, especially fish, which you can savour at the Ostermalm market, bringing together tourists and locals alike.

Until 1775, Jews were banned from entering Sweden, unless they agreed to convert to Christianity. That year, an engraver named Aaron Isaac pleaded his case for living in Stockholm without converting. Long administrative procedures, from office to office, even led to a meeting with Gustav III, King of Sweden. The king granted this right. Thus began the official settlement of Jews in Sweden.

Twenty years later, the synagogue housed in today’s Jewish Museum welcomed the Jewish community. The synagogue remained in use until 1870, when the small space could no longer accommodate the growing Jewish community of around 1,000 families.

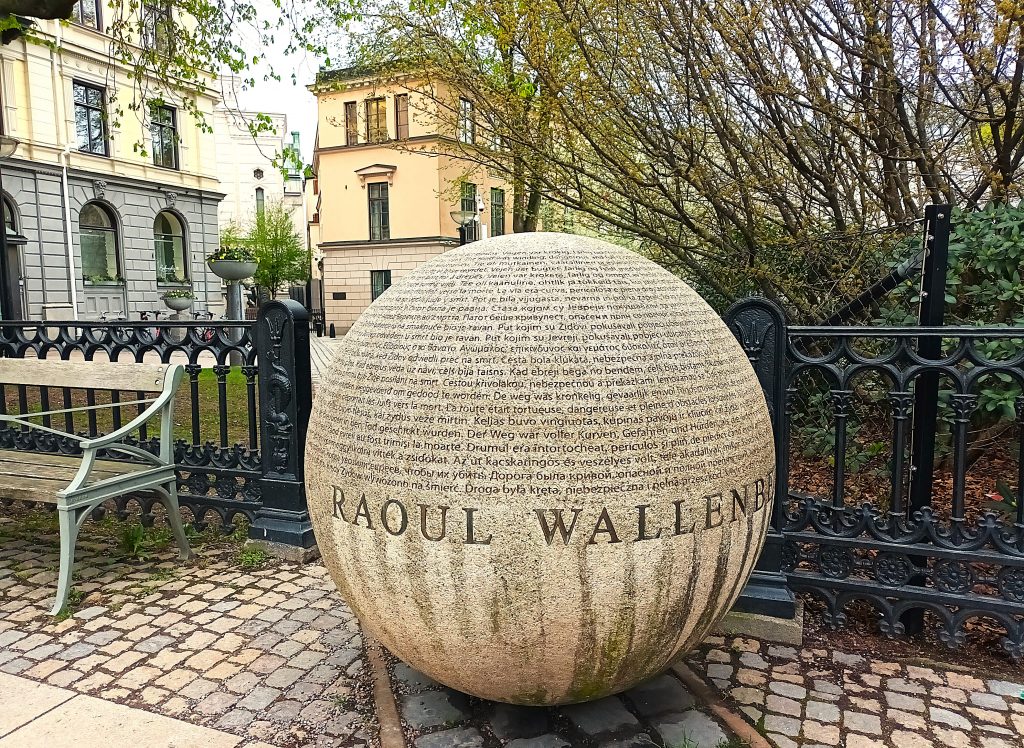

The Great Synagogue of Stockholm , which also serves as a community center, was built in 1870. It is located next to Raoul Wallenberg Square, named after the Swedish diplomat who rescued many Jews from Hungary and was arrested, then probably liquidated, by the Soviets.

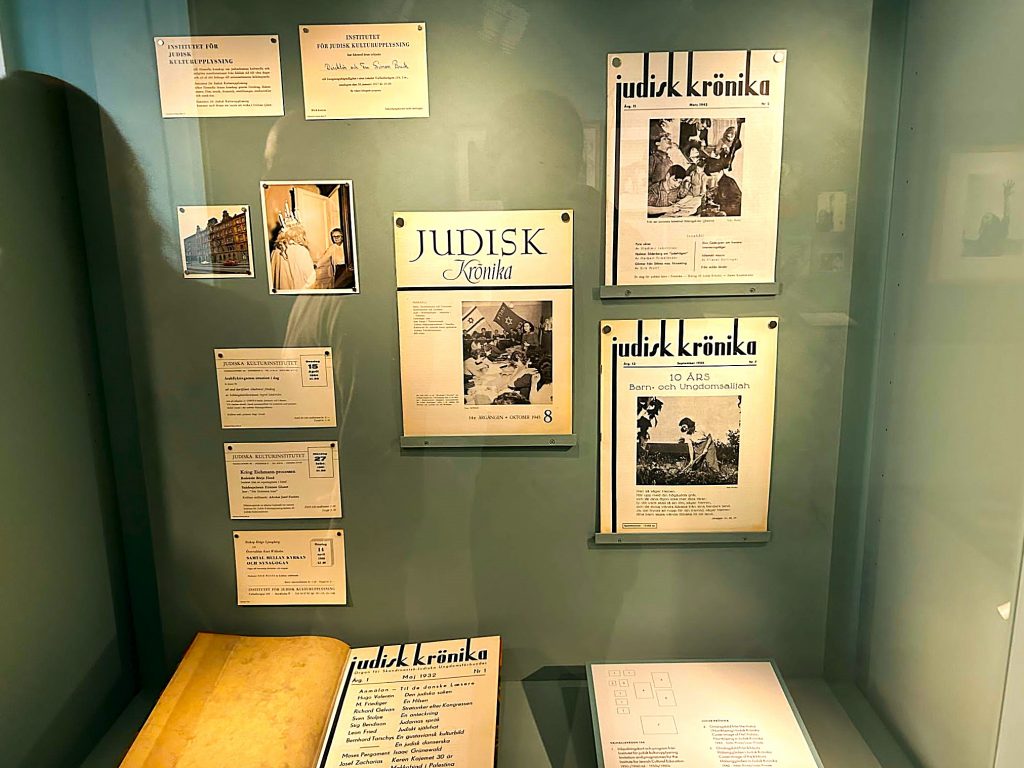

The oriental-style building can accommodate 1,000 worshippers following a massorti rite. In the synagogue’s community center, you’ll find a library whose main interest is the availability of the excellent magazine, Judisk Kronika, and historical works on Swedish Jews.

This modern Jewish community embraced the reforms underway in many Western European countries, as did others across the continent. Religious reforms were encouraged by the Enlightenment and the revolutionary spirit, but also by the national bond strengthened by the recognition of equal rights.

Sweden welcomed Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe at the end of the nineteenth century, fleeing pogroms. Living in the working-class districts of southern Stockholm, they established their own synagogue. Thus, Södermalm synagogue was built at the end of the 19th century. Jews from Eastern Europe worked mainly in textiles and commerce.

During the Holocaust, Sweden chose neutrality. A neutrality not necessarily appeasing to the Jewish community, which feared rapid geopolitical change. This fear was reinforced when, during the war, Swedish Nazi sympathizers began drawing up lists of Jewish compatriots to present in the event of a German invasion. Some Jews did not hesitate to buy weapons, just in case the situation evolved in this direction. On the other hand, let’s not forget that Sweden welcomed many Danish Jews who took refuge there during the formidable rescue operation.

Towards the end of the war, when it became clear that Germany was going to lose, Sweden adopted a more openly pro-Jewish policy. The country opened its doors to Jewish refugees and survivors, welcoming almost 10,000 people in 1945. As a result, Sweden’s Jewish population tripled in one year. Half of these new arrivals eventually chose to settle in Israel or the United States, but the other half preferred to stay on, enjoying the gentle Swedish lifestyle.

A memorial to the victims of the Holocaust was erected in Stockholm in 1998. It was designed by sculptor Sivert Lindblom and architect Gabriel Herdevall. It was inaugurated by Sweden’s King Carl XVI Gustav. It is composed of 8,500 stone tablets.

Today, there are several other Swedish synagogues. The Adat Yeshurun Orthodox synagogue contains furniture from a Hamburg synagogue vandalized during Kristallnacht. The other Polish-rite Orthodox synagogue, Adat Yisrael , is located in the Södermalm district, in a 17th-century building.

There are several Jewish cemeteries in Stockholm. The first was built by Aaron Isaac in 1776. It bears his name, Aronsberg . In use until 1888, it contains almost 300 headstones. The Kronoberg Jewish cemetery was built in 1787. It housed 200 graves until 1857.

As both cemeteries were very small, the Jewish community acquired additional land. In Solna, architect Fredrik Wilhelm Scholander built the chapel and gates of the Northern Jewish Cemetery . In 1857, the so-called “Mosaic Cemetery in the North Cemetery” was inaugurated. Scholander was also the architect of Stockholm’s Great Synagogue. Among those buried here is Nobel Prize winner Nelly Sachs.

The Southern Jewish Cemetery was built in 1952. Its chapel was designed in 1969 by architect Sven Ivar Lind. Nowadays, most burials take place there.

The Jewish Museum of Sweden

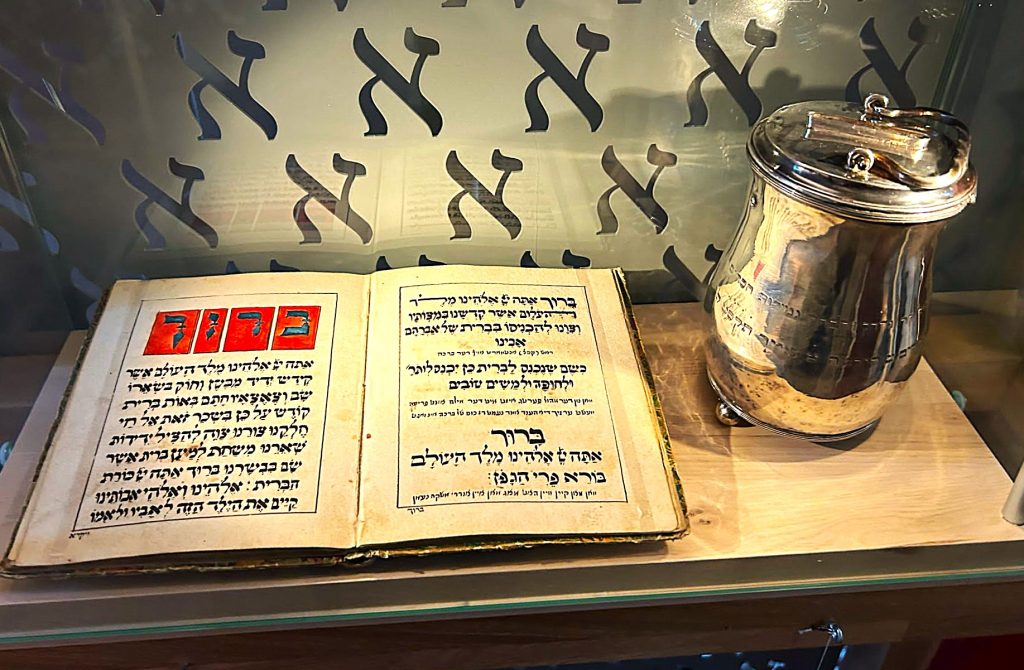

The museum was founded in 1987 by Aron Neuman, a patron of the arts, then closed due to a move to the Gamla Stan (“Old Town”) district, in the country’s oldest preserved synagogue. Apart from the structure itself, which is still easily identifiable, the museum still possesses a few elements of the old synagogue, including the aron and the bimah.

When the synagogue moved in 1870, the Jewish community sold the building to a priest, and it was transformed into a chapel. Over time, the building changed function, becoming a police station and then an architect’s office. It wasn’t until 2019 that the Jewish Museum of Sweden opened its doors, leasing the space from the city. Renovations were carried out, but with an eye to preserving the synagogue’s original setting. Some walls were repainted white, and layers of paint were removed elsewhere to reveal old paintings that had once stood there. These paintings are among the few remaining today in the North German style. Most synagogues decorated in this style were destroyed during the Holocaust.

The museum’s permanent exhibition recounts the contemporary history of the Jews in this country, which began in 1775. It shows the settlement of the first Jewish community, with its leading figures.

Then, gradually, the arrival of Eastern European Jews in the nineteenth century. A collection of clothes hangers symbolizes the arrival of this population, who worked mainly in the textile industry and created some of the biggest local brands, as can be seen on the labels on the hangers.

One area of the museum is dedicated to the persecution of Jews during the Holocaust. On display is a passport bearing the “J” stamp, which was required for entry into both Sweden and Switzerland, neutral countries during the war. They asked the German authorities to stamp passports in this way in order to deny Jews access to their territory. Preserved Jewish ritual objects from other European communities are also on display.

The museum’s permanent exhibition ends on a more positive note, presenting the development of contemporary Jewish life in Sweden. It highlights the reception of newcomer refugees, survivors of the Holocaust, and their contributions to the evolution of Swedish Jewish life. With some objects reminiscent of that era, notably those used for kiddush. And other ancient objects, including the small metal boxes found in many homes, collecting donations for the KKL and other institutions of the reborn state of Israel.

Among the new items acquired by the museum is an film recounting the settlement of Jewish Holocaust survivors in the small town of Boras. They settled there to work in the textile factories, helped by Jewish industrialists from Stockholm. Sweden’s rural exodus and the disappearance of many factories meant the end of many small communities, including this one, which is why this film and other objects in the Swedish Jewish Museum are so precious.

What used to be the balcony, where the women sat in the synagogue, is now home to small temporary exhibitions. These focus on Jewish rituals. In 2025, for example, religious headgears are on display, with both ancient and modern photos. Original items include kippot with a horse, a beloved Swedish symbol.

Major renovations were undertaken at the museum in 2024. The entire first floor was refurbished. The museum’s administrative staff left the first floor, in order to devote these spaces to temporary exhibitions, reserved for more contemporary subjects.

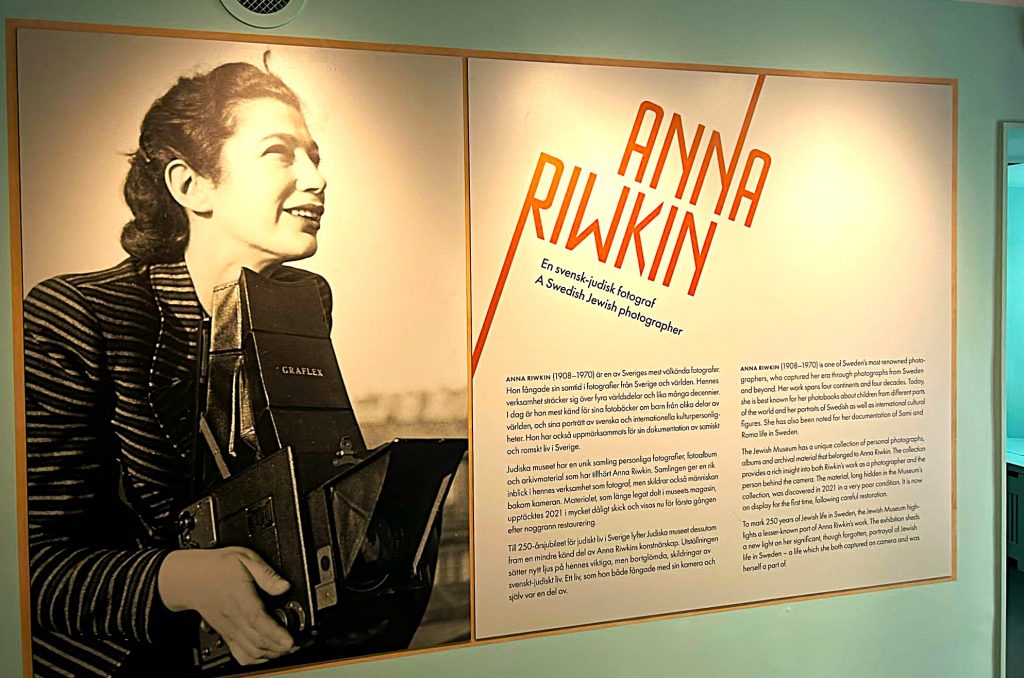

In 2025, the museum hosted a magnificent temporary exhibition dedicated to Sweden’s most famous photographer, Anna Riwkin (1908-1970). She is best known worldwide for her books dedicated to young people.

The exhibition features not only photos, but also numerous personal objects and writings. These include her diary, wedding album and portraits of her family taken when Anna was a teenager.

Born in Russia in 1908, she emigrated to Sweden with her family at the age of 7. Unlike the majority of Eastern European migrants at the time, her family was not very religious, but was very involved in the Zionist movement. Anna and her siblings found happiness in artistic practice, devoting their lives to it: author, translator, painter and photographer… None of them had children, except for their work.

At the age of 20, Anna Riwkin married Daniel Brick, one of the leading figures in Swedish Jewish life. In 1932, this journalist, publisher and committed intellectual founded Judisk Krönika, the Swedish equivalent of the Jewish Chronicle, a publication that still exists today. In this exhibition, you can see the letters they wrote to each other.

Throughout her career, Anna Riwkin took photos for various publications. She was known for her dance photos, portraits and advertisements. These constituted the first phase of her career, the second being devoted to reportage. From the 1930s onwards, she travelled all over Sweden and the world, photographing a whole host of people. As a result, she became a leading reference for the documentary presentation of Sami and Roma life. Anna was also the first to present a non-exotic image of these populations. Children feature prominently in her photos. Anna declared in an interview that, having been unable to have children of her own, the portraits of all these children helped to compensate for this pain.

She spent a lot of time abroad. The result was the annual publication of two collections of photos dedicated to these countries, one for adults and one for children. The photos were accompanied by texts written by Swedish authors. These books met with great success.

Less well known to the general public, however, and exhibited here, is Riwkin’s commitment to the presentation of Swedish Jewish life. So much so, that for four decades, from the 1920s to the 1950s, she was its principal documentarian. This involved a variety of projects, both personal and commissioned by community bodies. And, of course, photographs for the Judisk Krönika, run by her husband.

The exhibition features many moving photos from the first half of the 20th century: the arrival of Jewish refugees in Sweden, portraits, and the façade of the former synagogue that became this museum. Her commitment to Jewish culture was not limited to his talent as a photographer. Daniel Brick assisted her in founding the Institute for Jewish Cultures in Sweden.

The exhibition closes with her abundant photographs taken in Israel in the 1940s, before and just after the creation of the state. Anna Riwkin did not limit herself either geographically or culturally, crossing the country from end to end. Capturing images of its diverse population: men, women and children from different cultures, religions and living quarters. She published collections based on these photos, with texts written by Daniel Brick. Both books can still be found in the homes of Swedish Jewish families today. For decades, she was recognized as the leading photographer of Israeli life, her photos becoming a worldwide reference on the subject.

Swedish Museum of the Holocaust

The museum is housed in a building near the railway station. Two exhibitions are presented in the left and right sections of the Swedish Museum of the Holocaust . Opposite the entrance is a small room showing videos of Holocaust survivors answering various questions. Depending on the themes requested by visitors, the computer presents these videos, recorded earlier. A very contemporary form of memory sharing.

The 2025 temporary exhibition on the left-hand side of the museum looks at how the Swedish press dealt with the advent of Nazism and the Holocaust. The exhibition features many newspaper covers and newsreels shown in cinemas.

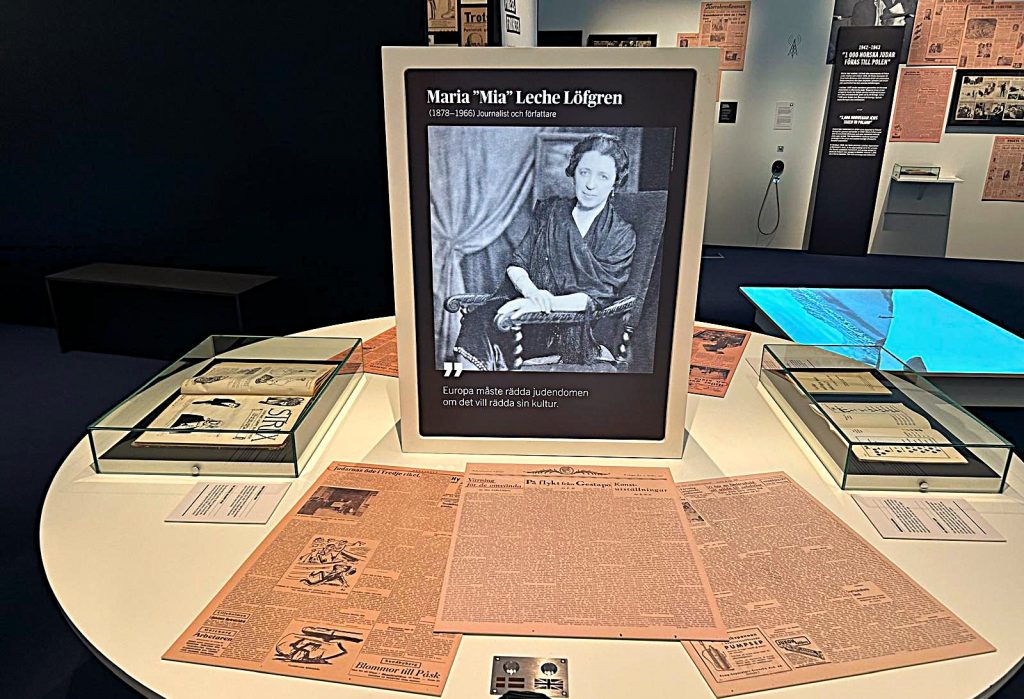

While some Swedish newspapers were coy in their presentation of the advent of Nazism, or chose pastel words to describe the murders, most condemned the Nazis’ policies. The latter did, however, have some allies in the press. You can, for example, discover the story of journalist Maria Leche Löfgren, who was one of the greatest campaigners for the diffusion of information on the fate of the Jews.

Also of interest are old newspapers from before the Second World War, attacking Jews. With the same far-right or far-left caricatures found in other European countries at the time, and now back in fashion: the Jews being accused of being a deicidal people by the former, or of conquering the world by the latter, or even, as some claim today, both at the same time.

The signs explain that the Swedish government put pressure on the press not to reveal too much about the fate of the Jewish deportees. They also mention that when the Germans began deporting Jews from Norway in 1942, many Swedes signed up to defend the Jews. And that the country welcomed Danish Jewish refugees, not forgetting of course the courage of Raoul Wallenberg. Among the anti-Nazi portraits, we discover the story of Amelie Posse (1884-1957).

As in many contemporary exhibitions devoted to the Holocaust, much space is given to the testimonies of the last survivors and the Righteous and their families who saved Jews during the war. The museum also pays homage to authors, journalists, politicians and other individuals who had the courage to oppose Nazism.

The temporary 2025 exhibition on the right-hand side of the museum is dedicated to Roma victims of the Holocaust. It shows the stages leading up to their deportation in Europe. It also pays tribute to their uprising in a concentration camp when the Roma rebelled, following a Polish political prisoner’s warning of their planned fate.

The exhibition tells the story of many families: men, women and children… how they were arrested and what happened to them afterwards. Who survived and who perished during the Holocaust. The exhibition also looks at how the Roma were discriminated against in Sweden for a long time. And how long it took the authorities to recognize this fact.

Among the moving stories told is that of Rose-Marie. A survivor of the Holocaust with her mother who suffered from numerous health problems and had no choice but to put the 5-year-old in an orphanage for two years. At school, Rose-Marie was bullied by many pupils who couldn’t understand why she had a number tattooed on her arm. The children thought it was a prisoner’s number. At the age of 18, Rose-Marie had the number removed from her arm. In 1952, she managed to trace her father in Germany, who had survived 7 years of captivity in Russia. The family was finally reunited.