The presence of Jews in this industrial city in northern England is relatively recent. At the end of the 19th century, Zachariah Bern from Newcastle-upon-Tyne created the impetus for the establishment of a community in Gateshead.

Creation of Gateshead’s yeshiva

In 1929, his son-in-law, Moshe David Freed, along with other students such as David Dryan and David Baddiel, established a yeshiva in the city.

Under the direction of Rabbi Nachman Landinski and his assistant Eliezer Kahan, it welcomed students from all over Europe fleeing Nazism. E.G. Dessler founded a kolel there.

Development of jewish studies

Other structures made it possible to expand the yeshiva and its reception capacities. So, in 1966, the Gateshead Foundation for Torah was created to promote Jewish literature.

The yeshiva has since become a national and even European benchmark. At the turn of the century, there were 1,500 Jews in Gateshead. The yeshiva has nearly 300 students from all over the world.

The first administrative traces of the presence of Jews in Cambridge seems to date from the 13th century. About fifty Jewish families are recorded in documents between 1224 and 1240.

In 1275, the Jews were expelled from Cambridge and the rest of the region under the tutelage of Eleonore de Provence, mother of Edward I. The latter expelled the Jews of the Kingdom by the Edict of 1290 which was not annulled until 1656 by Oliver Cromwell.

Jewish participation in the intellectual life

Returning to Cambridge several centuries later, Jews contributed to the intellectual life of the university town. Among them, Isaac Lyons, Isaac Abendana, Joseph Crool and Herman Bernard.

While there were many Jewish teachers over the centuries, students were only admitted as non-graduate free listeners until 1856. When this discrimination ended, Jews actively participated in the development of the university, as students, professors and administrators.

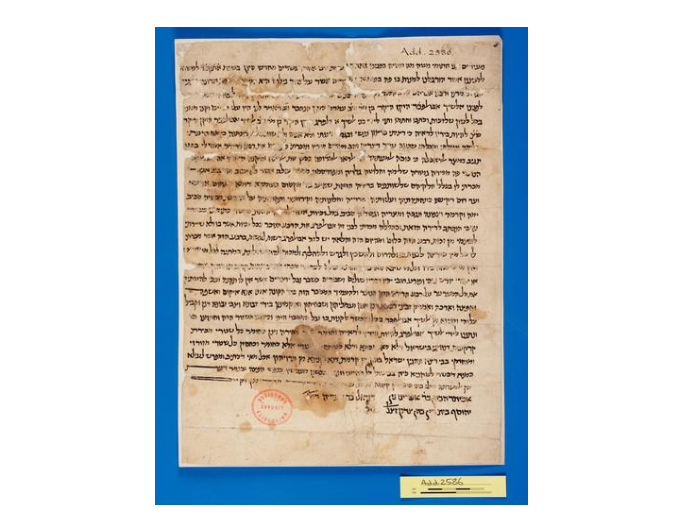

Hebrew-language manuscripts collected by orientalist Thomas Erpennius were donated to the University Library in 1632. Fifteen years later, the library housed the Hebrew books of Italian rabbi Isaac Faragi.

The visit to the Jewish cultural heritage of Cambridge, a prestigious university town, takes place above all within its collection of rare and ancient manuscripts, which total more than 3,000 sources.

The treasures of the Cairo genizah

Another university acquisition is the Taylor-Schechter Cairo collection. It is the largest collection of medieval Jewish manuscripts. For a thousand years, the Jewish community of Fustat in Cairo kept its ancient writings and books in the genizah of the Ben Ezra synagogue.

In 1896, Cambridge professor Solomon Schechter studied these archives on the spot, with the financial support of the leader of St John’s College, Charles Taylor. He obtained permission from the Egyptian Jewish community to bring the documents to Cambridge. The fund consists of 193,000 manuscripts. Among them are religious but also civil texts, on the philosophy of Sufism and Shiite currents, Arabic poems, medical books and letters. The interest of the archives therefore goes beyond researchers in Jewish studies and is addressed to all medievalists. Some of the archives digitalized can be accessed on this link.

The Mosseri Collection

The Cambridge Library also received 7,000 documents from the Mosseri family for a 20-year loan. The Jacques Mosseri Genizah Collection, assembled by this Egyptian businessman at the start of the 20th century, is also of great interest to researchers. Some of the documents are accessible online on the University of Cambridge website.

Since the end of the last century, the city has had around 500 Jews, and a similar number of Jewish students at its university.

The Cambridge Traditional Jewish Congregation welcomes many students. Like the Beth Shalom Liberal Synagogue , opened in 1981. The Chabad House was founded in 2003.

Around 1730, the first Jews settled in the city of Birmingham. The city’s first glass kiln was built by Meyer Oppenheim around 1760. A synagogue was established in the 1780s in the Froggery district. Another synagogue was built in 1809 but was destroyed, along with other places of worship that did not meet the standards of the time, during riots in 1813. It was rebuilt and enlarged in 1827.

Development of Jewish life in English cities

Thanks to the Industrial Revolution of the 1830s, cities in the north of England such as Manchester, Liverpool and Birmingham attracted many workers and other workers from different countries but also English cities in the south. Among them, new Jewish immigrants. Most of these new arrivals came from Germany, the Netherlands and Poland.

Immigration continued until the 1830s, when America then became the primary destination for Jews fleeing wars and pogroms on the European continent. In the 1830s, rather middle-class Jews from Germany also settled in England.

Working in different fields

Gradually, therefore, the number of Jews in the north of England increased markedly. So, in 1851, there were 1,500 Jews in Liverpool, 1,100 in Manchester and 780 in Birmingham. This era saw the arrival of Jews from Poland and Russia who made up a quarter of Birmingham’s Jews in 1851. The active life of the city’s Jews was mainly in four areas: glaziers, slipper makers, tailors and peddlers. The precarious situation of the Jews was then the image of the entire English population. The Singers Hill Synagogue is now Birmingham’s main Jewish place of worship. He was born in 1856. 700 Jews then lived in the city.

From 1881 to 1914, between 120,000 and 150,000 Jews from Eastern Europe arrived in the country. A good part of them aspired to continue the road towards the United States.

While nearly 60% of those who remained chose London, a significant proportion also opted for Manchester and a little less for Liverpool and Birmingham, mainly tailors and merchants.

Low Jewish presence in this major city

On the eve of World War I, there were 300,000 Jews in England. There were then many Jewish tailors but also restaurateurs of the famous Fish & Chips. Among them, 6,000 in Birmingham. During the Second World War, the bombardments destroyed many places in the city.

This number reached 6,300 in 1967, Birmingham being the largest city with the weakest Jewish presence in the country. This figure is decreasing in particular with the exodus in the suburbs and surrounding towns, but also with movements between districts. Thus, in 1963 saw the light of day the Solihull and District Hebrew Congegration . Later, the Central Synagogue moved to Pershore Road, the New Synagogue went to Park Road, and the Progressive Synagogue moved to Sheepecote Street.

In the 1980s, more Jews left the city, mainly for London, Manchester and Israel. There were then only 3,000 Jews in Birmingham. A figure that still remains very low in 2025.

There are two Jewish cemeteries in Birmingham: The Witton Cemetery and the Brandwood End Cemetery .

Jews settled in the English city of Brighton and Hove from the mid-18th century. The city was then a famous vacation spot. Among the large Jewish families who stayed there regularly, we can mention the Goldsmids and the Sassoons.

There was a first attempt to establish a community there in 1800, but it was unsuccessful. In 1821, a new attempt met with great success. At the beginning of the 19th century, in Brighton as elsewhere in England, the majority of Jews lived in great precariousness. The Brighton Regency Synagogue was built in 1824 but sold fifty years later and has since been converted into an apartment building.

The beautiful Middle Street Synagogue

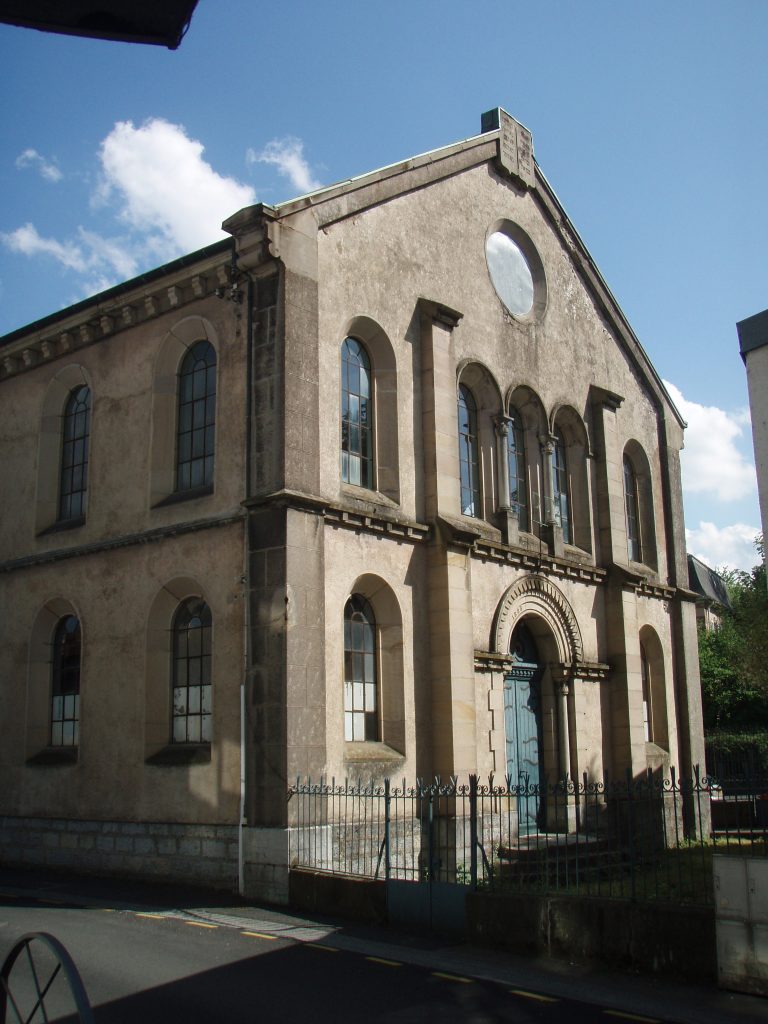

The main Jewish place of worship in Brighton and Hove is the Middle Street Synagogue , built in 1875 by architect Thomas Lainson. It had a capacity of 300 people, six times more than the previous synagogue. The Sassoon family contributed to many institutions and social activities, as well as to the construction of the synagogue. With very original architecture, the synagogue has a mixture of styles between Renaissance and Neo-Byzantine on the outside and a rose window at the top of the main facade.

As for the interior, it looks more like a basilica and is also imbued with a Neo-Byzantine style. Iron, glass, marble and mosaic combine to offer a wide decorative variety. Although less used today, it remains accessible for visits provided you prevent it in advance.

Different of Jewish streams represented

In the 20th century there were five synagogues in Brighton and Hove. Synagogues of various currents: Orthodox, Liberal and Reformed.

A 1968 census indicates that there were 7,500 Jews in Brighton and the nearby town of Hove at the time.

In 2025, the situation seems to be more pessimistic. The Jewish population is aging, and kosher shops are have gradually been closing. The Jewish community of Brighton gathered on 7 October 2024 to commemorate the one-year anniversary of the pogrom in Israel in front of the memorial. In the 11 months of its existence, the memorial has been vandalised around twenty times by anti-Semites. Four active synagogues remain in Brighton and Hove.

The astonishing Progressive synagogue

The Hove Hebrew Congregation Synagogue , built in 1930 by Mr K. Glass. To visit for its Art Nouveau style.

Also very original in style, marked by the international movement of the 1920-30s close to modernism, the Brighton and Hove Progressive Synagogue was founded in 1935.

There is also the Brighton and Hove Hebrew Congegration opened in 1959 and the Brighton and Hove Reform Synagogue built in 1967 by Derek Sharp.

Recently, the Reformed Synagogue has grown in popularity, attracting young Jewish families who were initially less involved. The city also hosts a Chabad center.

There seems to be around 2,700 Jews in Brighton and Hove today. Ralli Hall , the town’s community center, attracted mainly young people in the 1970s.

Brighton is a city that prides itself on its open and tolerant atmosphere. And yet, in the two years following the 7 October pogrom, a memorial dedicated to those murdered by Hamas was targeted more than 50 times and completely destroyed five times in Hove…

Today, an older population, including some of these former young people, occupy the premises. But the villa, a listed monument, remains a place where different populations meet, enjoying its original setting.

There are three Jewish cemeteries in Brighton and Hove. The Florence Place Old Jewish Burial Grounds , the oldest opened in 1826. Then, the Meadow View Jewish Cemetery , an Orthodox cemetery built in 1920. And finally sections of the Hove Cemetery where non-Orthodox Jews are buried.

During the 1808 census, only the presence of 34 Jews was counted in the department.

In 1816, Simon and Michel Lipman, merchants, asked for the possibility of obtaining a Jewish cemetery in Brest. Simon’s house was used as an oratory for the community of Brest.

50 years later, there are 59 Jews in Brest. At that time, a letter from the sub-prefecture mentioned the existence of an “Israelite temple” and the presence of an officiating minister. It is the first recognized Jewish community in Brittany, but its development has been rather modest.

A Jewish religious association in Brest (ACIB) was founded by Emile Levy and André Hassoun in 1962, upon their arrival from Tunisia. It brings together Ashkenazi Jewish families, some of whom have been present since the beginning of the 20th century, and Sephardic families, most of whom came from Tunisia and Algeria. The official inauguration of the ‘Beth Hafsé Aaretz’ took place on 15 February 1987, in the presence of the Mayor of Brest, Georges Kerbrat, and Chief Rabbi René Samuel Sirat.

On 29 December 2024, the Jewish community of Brest celebrated the Festival of Lights in the presence of the Chief Rabbi of France, Haïm Korsia, and representatives of Brest’s Jewish, Catholic and Muslim communities.

At the confluence of the Ille and the Vilaine, Rennes was an important city in the Middle Ages. Today known for its large student population and as a very prosperous city appreciated by tourists for its many monuments, such as its magnificent theater.

During the 1808 census, only the presence of 11 Jews was counted in the department. The resettlement of the Jews from Rennes took place in the middle of the 19th century. In 1851, there were thus 8 Jews in the city, including 7 soldiers in garrisons based in the city and 1 Jew from Germany living in Rennes.

In 1872, the figure increased slightly to 28. Among them, 8 soldiers, including the parents of Jules Isaac. His father even became a lieutenant colonel in the artillery and an officer of the Legion of Honor. The French historian and pioneer of Judeo-Christian friendships was born in Rennes.

University city, Rennes counts its prestigious teachers Victor Basch and Henri Sée. During the Dreyfus trial, and faced with a resurgence of anti-Semitism in the city, a small group founded the Rennes section of the Human Rights League in Victor Basch’s own home.

In 1940, there were 124 Jews in Rennes and 372 for the entire department. The Jews of Rennes organize themselves as a community formed in the 1960s, rebuilt with survivors of the war and the arrival of Jews from North Africa.

The Edmond J. Safra Center , inaugurated in 2002, currently serves as a worship and cultural center for the Jewish community of Rennes.

At a time when anti-Semitic acts are on the rise, Ginette Kolinka, who was deported to Auschwitz-Birkenau at the age of 19 and is one of the last survivors of the Holocaust in France, is continuing her tireless meetings with young people. Her aim is to bear witness and pass on the memory. This is what she did on 22 January 2024 at the Assomption secondary school in Rennes.

Sources : Ouest-France

Rue Chateaubriand (anciently rue Buhen , nicknamed the “rue des juifs” near the Qui qu’i ‘en grogne tower, leads to what is now Place Chateaubriand.

As early as the 16th century, we find traces of a Jewish presence. Mainly families of craftsmen and traders. The great writer Chateaubriand indicates in Mémoires d’Outre-Tombe that he was born in “this dark and narrow street of Saint-Malo called the rue des Juifs”.

The history of the Jews in Saint-Malo knew an astonishing episode. In 1731, an order of the Council of State limited the commercial activities of the Jews by forbidding them to “traffic, sell or debit their goods in any city of the kingdom other than those where they were domiciled”. This judgment did not concern fairgrounds.

Israel Dalpuget and Moïse Petit, fairgrounds from Saint-Malo, were banned from the Nantes fair in 1741. They obtained the support of the mayor of Saint-Malo and the aldermen, as well as that of the Countess of Conti. The conflict lasted for twenty years.

During the 1808 census, only the presence of 11 Jews was counted in the department.

In 2023-24, as part of a remembrance project, two final year classes and their history teachers from the Lycée Jacques-Cartier in Saint-Malo retraced the history of families from the city who were deported. Starting with Daniel, murdered on arrival at Auschwitz in 1944 at the age of 3. By focusing on Saint-Malo, meeting historians and researchers and renewing contact with the family members of these deportees, the pupils were able to put faces to names, live in the same neighbourhoods and understand the dangers of the return of anti-Semitism.

Sources : Ouest-France

Land near the ramparts of Nantes was sold by Guillaume to Théodore, a Jew from Rennes, and to the Jews of Nantes to establish a cemetery. Nevertheless, five years later, the Jews of the region are victims of looting and murder.

Following the banishment of the Jews from Brittany ordered in Ploermel on April 10, 1240, it was not until the end of the 15th century to see the return of the Jews. Gradually, the installation of Marran families is authorized by royal policy.

Philip II, King of Spain, banished the Jews who settled mainly in Nantes and Bordeaux. At the beginning of the 1590s, Portuguese Jews stayed in Nantes. Among them was Abraham Espinoza, the grandfather of the famous philosopher, who then settled in Amsterdam.

In 1636, Jews from Bayonne, expelled during the Franco-Spanish war, took refuge in Nantes. At the end of the 18th century, Nantes merchants attacked newly established Jewish merchants. The local press shows support for these victims.

During the 1808 census, only the presence of 25 Jews was counted in the department. In April 1835, the Jews of Nantes, who counted 18 families, asked the mayor for permission to build a temple on Franklin Street, in order to exercise their worship. The first synagogue thus saw the light of day in this year.

The censuses show a variation in the population. Thus, in 1841, there would be 154 or 240 Jews according to different estimates. 105 in 1854, then 133 in 1861.

In 1871, the synagogue on rue Copernic was inaugurated. From 1882 to 1929, Samuel Korb was the rabbi. Two of his sons were killed in the war.

In a census in 1942, the Vichy government counted 531 Jews in Nantes. A year later, there were only 53 left, following arrests and deportations.

The community of Nantes slowly rebuilt itself after the war. Thus, there were only 25 Jewish families in the city in 1960. The arrival of Jews from North Africa during the decade allowed development, and in 1969 there were 500 Jews in Nantes. The synagogue is also used today as a community center.

In February 2024, the Jewish community of Nantes celebrated the 154th anniversary of the synagogue, built in 1870. To mark the occasion, the Association culturelle des amis du judaïsme de l’Ouest opened its doors for a week of tours, an exhibition, and lectures on the history and daily life of the Jewish community in Nantes and the department.

On 21 July 2024, a ceremony was held in front of the 50 Hostages monument in memory of the round-up on 16 July 1942, during which a descendant of the Righteous testified.

Fabrice Rigoulet-Roze, Prefect of Loire-Atlantique and Pays de la Loire, Ariel Bendavid, Rabbi of Brittany and Pays de la Loire, and René Gambin, head of the Jewish community in Nantes, spoke at the ceremony. Gambin recalled the courage of the Righteous, who risked their lives to save Jews and set an example for all generations of French people. Olivier Château, deputy mayor of Nantes, then laid a wreath in memory of the victims of racist and anti-Semitic crimes and in tribute to the Righteous of France. Gilles Gautron, ‘grandson and son of the Righteous’, then told the story of the Poitiers network to which his grandparents belonged, and how his family saved Jews during the Holocaust.

Sources : Ouest France

The presence of Jews in Montbéliard and in the region seems to date back to the 13th century. The expulsions will cause the departure of the Jews from the territory. There is a trace of a mention of a court painter, Solomon the Jew, in the 16th century.

In the spirit of the French Revolution and the emancipation of Jews from France, mainly from Alsatian families, are settling in the region again.

Thus, in 1793, Montbéliard again welcomed Jews. They will be 89 listed in 1826, then 221 in 1876. During the 19th century, Jews gathered in private accommodation or rented rooms to celebrate their worship. The Montbéliard synagogue was inaugurated on November 29, 1888.

Few Jews remain in Montbéliard today, but some residents are making great efforts to ensure that services are still celebrated there.

Since September 2025, a street in Montbéliard has been named after a survivor of the roundup that took place in the city on 24 February 1944. The street was named during the lifetime of Pierre-Michel Kahn, the last witness and survivor of this roundup. The street is located in the Hauts du Près-la-Rose neighbourhood.

A ceremony was held in the presence of Kahn and his family, as well as the mayor of Montbéliard, Marie-Noëlle Biguinet, and the deputy mayor of Ludwigsburg in Germany, Andrea Schwarz. Aged 11 in 1944, he was saved by the resistance fighter Lou Blazer, who was honoured with the title of Righteous Among the Nations in 1966.

Source: L’Est Républicain

It seems that the presence in Seine-et-Marne dates from the Middle Ages. Among the towns where they settled are Meaux, Lagny, Provins, Melun, Livry-sur-Seine, Bray-sur-Seine, Foljuif, Nemours, Château-Landon, Brie-Comte-Robert, Montoix, Pontault-Combault, Nangis, Lizy-sur-Ourcq, Coulommiers, Montereau-fault-Yonne, Donnemarie-en-Montois and Herbeauvilliers.

Following the 1394 expulsion and the gradual return of the Jews to France, the Jewish presence in Fontainebleau probably dates from the King’s stays in the castle, being more professional or intellectual than residential. François I probably took his Jewish doctor to Fontainebleau, had a Jewish doctor from Constantinople in 1538. Elie de Montaldo, personal doctor of Marie de Medici and the future Louis XIII, obtained permission to practice his faith.

The Royal Library of Fontainebleau had Hebrew manuscripts before its reunification at the National Library. Queen Christina of Sweden, who was staying at the castle in 1657, received from the hands of the Christian scholar Gilbert Gaulmin a hundred Hebrew manuscripts. Father Antoine Guénée, who died in Fontainebleau in 1803, was the author of “Letters from some Portuguese, German and Polish Jews to M. de Voltaire” and had vigorous exchanges with him about the anti-Semitism of the philosopher. A stele erected in his homage is currently in the Fontainebleau hospital.

In 1784, Jews settled in Fontainebleau. In the 1808 census, the community numbered 121 Jews, the majority of whom were children. Most have surnames from Alsace. At the end of the century, the city had a synagogue located rue des Trois Maillets, then another in the ruelle des Maudinés. In 1857, the community inaugurated a new temple, designed by architect Nathan Salomon.

During the occupation, the synagogue was degraded and then burned down. In the aftermath of the war, the community was rebuilt thanks to the return of exiled Fontainebleau Jews and Sephardic Jews who came in the 1960s.

The official formation of a community in Clermont-Ferrand dates back to 1808, when Israel Waël, who then headed it, donated a garden to establish a Jewish cemetery.

David Marx, the Chief Rabbi of Bordeaux, inaugurated the Clermont-Ferrand synagogue on March 20, 1862. The synagogue on rue des Quatre-Passeports was built in a private house by local architect François-Louis Jarrier. This is thanks to a donation from Israel Waël’s son-in-law and new leader of the community, Vidal Léon.

During the Second World War, the Israelite Seminary settled there temporarily after the occupation of Paris. During the occupation of Clermont-Ferrand, many Jews were rounded up. The synagogue will remain in operation until 1943.

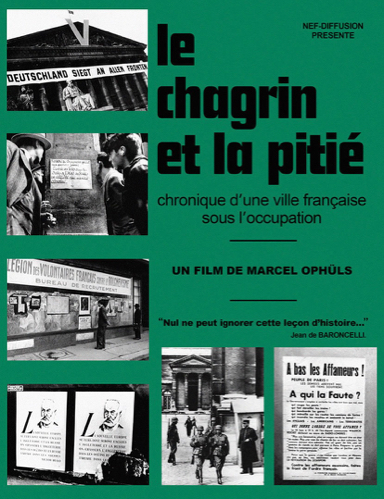

Clermont-Ferrand was the city chosen by French director Marcel Ophüls to shoot ‘Le Chagrin et la pitié’ (The Sorrow and the Pity). This poignant documentary about the Occupation brought to light many aspects of the war that had previously been overlooked, including acts of courage, but also everyday collaboration. Censored upon its release, it was broadcast on television in 1981, ten years later.

In the aftermath of the war, the synagogue was sold and then bought much later by the patron Edmond Safra so that it could serve as a cultural and educational space devoted to the history of the Jews and to the memory of the Righteous in Auvergne.

Thus, following major restoration work, the Jules Isaac Cultural Center has hosted here since 2013 a permanent exhibition, conferences and meetings in order to share the city’s Jewish cultural heritage and the history of the Righteous who saved them during the war.

A student city with magnificent museums, notably around the incomparable Stanislas Square, Nancy is one of the jewels of Lorraine, paying tribute to different periods of classical and modern art.

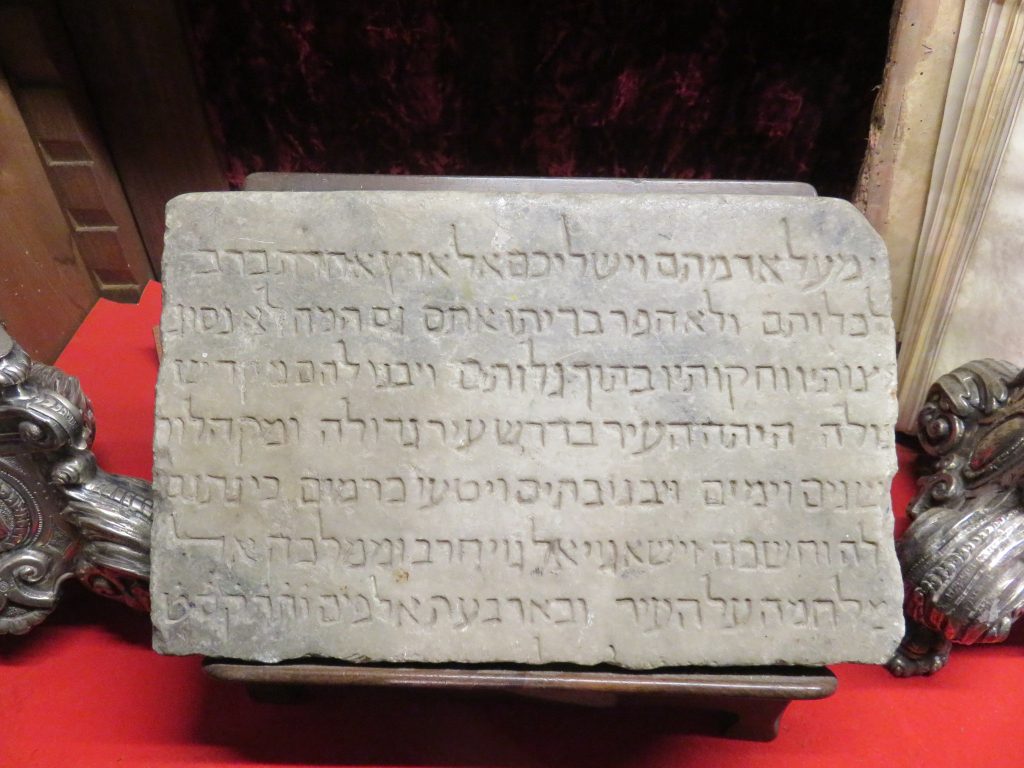

The Jewish presence in Nancy appears to date back to the Middle Ages, as evidenced by their expulsion in 1176. The Duke of Lorraine encouraged the arrival of Jews in the early 13th century. He allowed them to rent land in Laxou to use as a cemetery for Nancy and the surrounding villages. Before its disuse, following the expulsion of the Jews from the duchy in 1477, tombstones from this cemetery were used to build a church. They are the only material evidence of medieval Jewish life in Lorraine and are now on display at the Lorraine Museum. The museum is being renovated and is closed until 2029.

Five Jewish families, who had been granted residency in Nancy in 1636, were expelled in 1643. In 1698, Leopold, Duke of Lorraine, issued orders accusing the Jews of illegal contracts, but in 1710 he allowed them to officially resettle in Nancy. The Duke appointed Samuel Lévy, a banker from Metz, as Receiver General of Finances, before imprisoning and expelling him. In 1721, the Duke limited the Jewish presence. At the same time, he authorised a synagogue in Boulay and recognised a community leader, Moyse Alcan from Nancy.

In 1754, a ducal act recognised the Jewish community of Nancy, under Stanislas Leszczinski, who in 1737 authorised the Jews to choose their own rabbi. Their economic situation was precarious, as they were forbidden to practise trades related to agriculture and crafts. As a result, they were limited to certain commercial activities, as cattle, horse and grain merchants or peddlers.

Following a request to Louis XIV, the Jews were authorised to build synagogues, five centuries after the ordinance prohibiting them from doing so. Two synagogues were inaugurated in Lunéville (1786) and Nancy (1788), the first modern-style synagogues in France, built by the architect Augustin Piroux. The synagogue in Nancy was extended in 1841 and again in 1861. Its façade was transformed in 1935. What remains of the original building is the Holy Arch, with its marble columns and Corinthian style.

The winds of the Emancipation of 1789 were also blowing through Lorraine. It is in this region, also inspired by the work of Mendelssohn and the Haskalah, that the periodical Ha-Meassef had the most subscribers after Berlin.

The minister, Malesherbes, led a committee to this end, which included Isaac Berr from Nancy and Pierre-Louis de Lacretelle and Pierre-Louis Roederer from Metz. Pierre-Louis Roederer was the instigator of the competition organised by the Metz Society of Sciences and Arts, which asked candidates to consider the question ‘Are there ways of making Jews more useful and happier in France? Three dissertations were awarded the prize: those of Claude-Antoine Thiéry, Zalkind Hourwitz and, above all, Abbé Grégoire. The latter defended access for Jews to the rights and duties of citizenship at the National Assembly. His ‘Essay on the physical, moral and political regeneration of the Jews’ was published in 1789 after winning the Metz Society’s prize. The Emancipation of the Jews decreed on 27 September 1791 thus gave them access to the schools, professions and obligations of all citizens.

The Nancy Berr family was very much involved in these struggles, marking the successful integration of French Jews through Emancipation. Isaac Berr settled in Nancy in 1724, opening a luxury fabric business and becoming an ‘ordinary merchant’ to the Court. This success enabled his children, in particular Berr Isaac Berr, to become involved in the Emancipation of the Jews of France by becoming the representative of the Jews of Lorraine at the Estates General of 1789, and then by sitting on the Grand Sanhedrin. His nephew, Jacob Berr (1762-1836), published two pamphlets during the Revolution in favour of the Emancipation of the Jews. Lion Berr (1768-1826), Jacob’s brother, became in 1800 one of the first Jewish officers in the army.

Throughout the 19th century, Judaism in Lorraine declined in numbers, to the benefit of the Paris and Lyon regions. By 1853, there were just 1,400 Jews in Nancy. Marchand Ennery (1792-1852), Chief Rabbi of France, was one of the most important figures of the period and a testament to the dynamism of Lorraine’s Judaism.

The workforce that came to rebuild France after the First World War included many Polish Jews. They worked mainly in the textile, steel and chemical industries. In 1924, these Nancy Jews set up the Jewish Cultural Association (ACJ) . Here, they continued to share their Yiddish culture and set up an oratory for prayer.

La Revue juive de Lorraine, founded in 1925 by Robert Lévy from Nancy, is an important work of Jewish cultural heritage. It specialised in the publication of historical studies and texts furthering knowledge of Judaism. It was then directed by Rabbi Paul Haguenauer between 1927 and 1940, and then by Rabbi Simon Morali between 1948 and 1969.

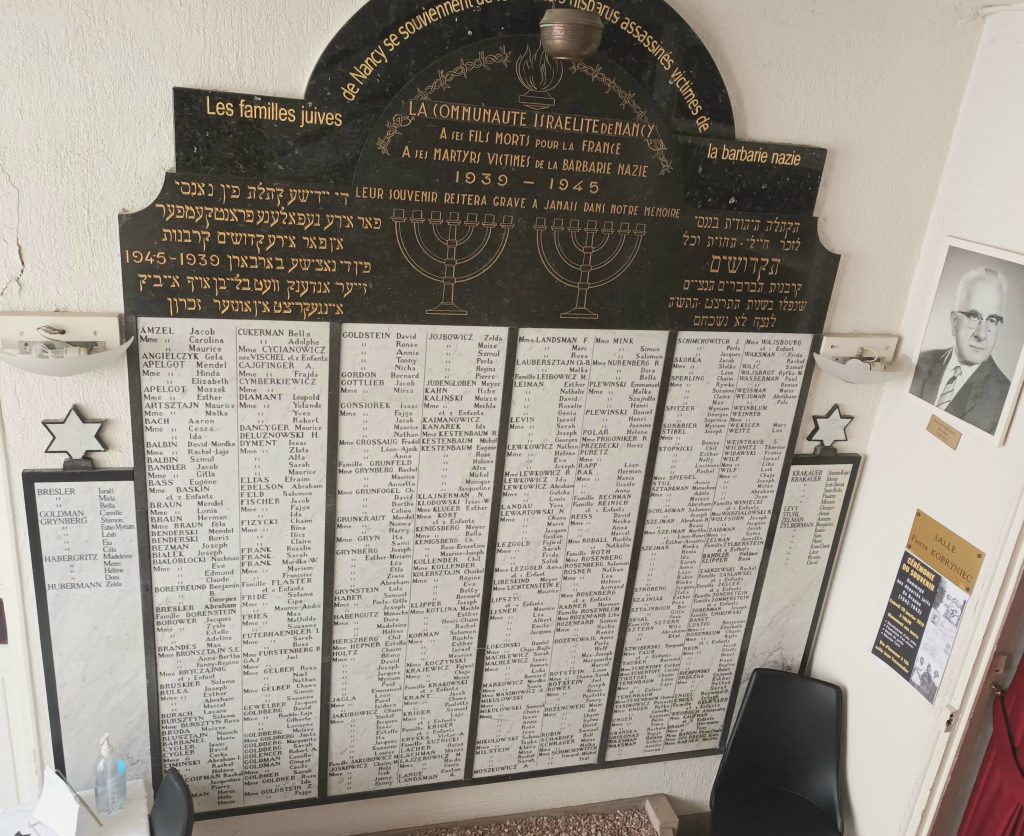

During the Holocaust, police inspectors warned Jews of an imminent round-up in July 1942 and rescued 385 of them. 32 Jews were arrested, either because they had not found a place to flee to or because they believed the warning. The rescue was organised by inspectors Edouard Vigneron and Pierre Marie.

They instructed their men Charles Bouy, Henri Lespinasse, Charles Thouron, Emile Thiébault and François Pinot to warn the Jews and also to help them leave the town, in particular by providing false papers or shelter. The story is told at length by Lucien Lazare in his Book of the Righteous. Other police officers working in different departments, such as Marcel Galliot, also saved Jews from Nancy.

Born in Bergheim in the Haut-Rhin in 1871, Paul Haguenauer left the German-occupied region and joined the army out of a sense of French patriotism. He became rabbi of Remiremont in 1898, then Chief Rabbi of Constantine in 1901 and Besançon in 1907. When the First World War broke out, he became a military chaplain throughout and was awarded the Military Cross for his bravery. In 1919, Paul Haguenauer was appointed Chief Rabbi of Nancy, where he was involved in a wide range of social work for the people of Nancy. He held this post until 1944, when he and his wife Noémie were arrested, detained in Ecrouves and then Drancy, before being deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered on 16 April 1944.

Gustave Nordon, the son of a poor Jewish family born in 1877 in Malzéville, became a labourer in a boiler works at the age of 12. Six years later, he published a manual that was a great success. In 1904, Gustave Nordon left Malzéville to set up his pipe workshop on rue des Tanneries in Nancy. Within the ‘Nordon Brothers’ company, he advocated and implemented improvements in workers’ living conditions, promoted the idea of “workers’ gardens” on land he bought for the purpose and helped them to buy property. He was also the first company director to grant 8 days’ paid holiday in 1930. During the Second World War, Gustave Nordon personally delivered food to Jewish prisoners at the Ecrouves internment camp. On 9 August 1941, he was ousted from his own company because of his Jewishness. He was replaced by his second-in-command Marcel Courtot, who secretly continued to support the prisoners and tried to save the Nordons from imminent arrest. Gustave and his wife Berthe were arrested on 2 March 1944, transferred to Drancy and then deported to Auschwitz, where they were murdered on 16 April 1944. A bridge has been named after Gustave Nordon . Following the Liberation, Marcel Courtot helped the 170 Jewish survivors of the Ecrouves camp. He was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations in 2001.

A plaque has been placed on the cathedral in tribute to Cardinal Eugène Tisserant, who was born in Nancy in 1884 and was recognised as Righteous Among the Nations in 2021. In 1939, he openly opposed the racial laws enacted in Italy. When Guido Mendes was dismissed from his post as director of a Roman hospital, Cardinal Tisserant supported him by awarding him a medal of honour from the Congregation of Oriental Churches. He tried to help many people obtain immigration visas, with varying degrees of success. Among them were the Mendes family, Rabbi Nathan Cassuto and Professors Giorgio Levi Della Vida and Aron Friedman, who found employment in the United States in 1938.

In 2013, four plaques were laid by the Nancy city council in front of the Didion, Braconnot, Ory and Jean Jaurès schools, at a ceremony attended by mayor André Rossinot, elected representatives and representatives of the Jewish community. The event was organised by Charlotte Goldberg to commemorate the 357 children aged between 4 and 15 who were deported and murdered in the camps. Charlotte Goldberg (1936-2016) was hidden ad a child by a Nancy woman and lost most of her family during the Holocaust. She regularly gave testimonies in schools and was also behind the installation of plaques at the Raugraff school in 1994 and at the Lycée Jeanne d’Arc in 2002.

The Place des Justes (Righteous Square) links the Rue du Grand Rabbin Haguenauer to the Boulevard de l’Insurrection du Ghetto de Varsovie . It was inaugurated in 2002 by Simone Veil, a survivor of the camps who went on to become President of the Council of Europe, and part of whose family is from Nancy. In 2018, one year after her death, Laurent Hénart, the Mayor of Nancy, inaugurated a Place Simone Veil opposite the station.

To perpetuate and salute this spirit of revolt against the occupying forces, the Association Culturelle Juive de Nancy (ACJ) celebrates the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising every year. The association also displays in its home a painting by Mané Katz honoring the uprising.

Nancy also has the André Spire community centre , which, like the ACJ, offers a wide range of cultural activities and has an oratory.

The arrival of Sephardic Jews in the 1960s brought a new religious dynamism. Representing a large part of the community today, the synagogue alternates Ashkenazi and Sephardic rites on the Sabbath. Great cantors such as André Stora and Michel Heymann have had a profound impact on Nancy’s Jews, as shown in the film devoted to the community by Josy Eisenberg in his weekly television programme.

The Jewish cemetery is located in the Préville cemetery, on avenue de Boufflers. At the entrance, a monument of remembrance pays tribute to the murder of part of Nancy’s Jewish community. The name of each missing child is inscribed on a small stele placed in front of shrubs planted by schoolchildren in 1987.

Nancy is home to some very fine and original museums. One of these, close to the cemetery, is the Villa Majorelle, the former property of the artist Louis Majorelle, with its many astonishing works of Art Nouveau. Speaking of Art Nouveau, the sublime Brasserie L’Excelsior, built in 1911, delights tourists and locals alike.

The Musée Lorrain , on the beautiful Place Stanislas, is a magnificent tribute to the region’s different historical eras. One of its rooms features numerous works of Judaica. Old prints and books are displayed in thirds so as not to damage them too much. In 2009, the museum hosted an excellent exhibition entitled “The Jews and Lorraine, a thousand years of shared history”.

Nancy’s Musée des Beaux-Arts is located on the edge of Place Stanislas, and features many works by European artists. In 2023-2024, it devoted an exhibition to local Jewish editor and translator René Wiener.

In July 2025, the plaque commemorating Yitzhak Rabin, located in Nancy’s Pépinière Park, was vandalised. This act was condemned by the mayor, elected officials and residents of Nancy.

Interview with the ACJ management team

Jguideeurope: How has the association evolved over time?

ACJ: Initially, the association was set up in 1924 by migrants from Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania and Romania in a different location. They wanted to have a distinct religious and cultural life. At the time, rue des Ponts, where the ACJ is located today, was home to textile manufacturing workshops and shmates sellers, as it was close to the market. When the first generations of migrants from this region arrived, they were quite poor and worked hard in these trades in order to send their children on to further education.

The association played its part with a functioning oratory. After the war, the association was reconstituted with slightly different sensibilities. It was marked by participation in all shades of politics: from left-wing Zionism to Communism and Bundism. This gradually led to an increasingly cultural and less religious life, hence the change of name from Polish Rite Jewish Religious Association to Jewish Cultural Association.

What objects symbolise these different eras?

Downstairs is the oratory and Mané Katz’s 1946 painting in tribute to the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. As well as his fresco of the Klezmorim, which has become the emblem of our association. It bears witness to the way in which Mané Katz felt at home in this community and wanted to thank it. At the entrance is the memorial stele with the names of all those murdered. We also have one of the largest Yiddish libraries in France, after those in Paris. It contains over 3,000 books.

What cultural activities are offered?

Our association continues to be active, bringing together Jewish and non-Jewish members with an interest in this culture. There are a number of highlights throughout the year. The second weekend in September sees the ‘Livre sur la Place’ festival, of which the ACJ is a partner. At each edition, at least one conference is organised in our association or at the Spire community centre. We also take part in the ‘Diasporama’ festival, where films with a Jewish theme are shown. And then, of course, there are the ‘European Days of Jewish Culture’, hosted mainly by the academic Danielle Morali, who is also the daughter of the former Chief Rabbi of Nancy, Simon Morali.

What about memorial themes?

The yizkor is performed every year at the association in front of the large marble plaque in memory of the deportees, before the yizkor in the synagogue. Commemorations are held regularly in memory of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, mainly in March and April. In November, in the Parc de la Pépinière, near the Kiryat Shmona alleyway , a town with which Nancy is twinned, Rabin’s assassination is commemorated in front of a tree planted there, in the presence of local officials. The municipality is also in the process of creating a memorial trail.

The Jewish presence in Lille is indicated from the Middle Ages. Many “rue des Juifs” existed in the region at this time, notably in Lille, Bavai, Maroilles and Sains.

In 1023, thirty Jews from Lorraine were authorized by the Count of Baudouin to settle in the North, in the towns of Hautmont, Bavai and Cambrai. Like other Jewish communities in the region, Jews were expelled from the Kingdom in 1394.

Their return to the region materialized on the eve of the Revolution, with the arrival of Alsatian Jews in particular. When the consistories were created, the North depended on that of Paris. In 1809, according to a census, there were one hundred and sixty-six Jews in Nord and sixty-three in Pas-de-Calais.

In 1891, the synagogue of Lille was inaugurated. The building is in the Roman-Byzantine style. The 17-meter nave is supported by twelve cast iron pillars symbolizing the twelve tribes. A sculpture of the Tables of the Law can be found atop the synagogue.

In 1932, more than five hundred Jewish families resided in Lille, 90 in the vicinity of the city, 116 in Valenciennes and its surroundings, 300 in Lens and its surroundings, 45 in Douai, 44 in Roubaix-Tourcoing, 33 in Dunkirk, 30 in Boulogne-sur-Mer, 16 in Calais and 40 in Amiens

Among the great personalities of the city, Armand Lipman, born in 1857, is the son of the Chief Rabbi of Lille: Benjamin Lipman. An officer out of polytechnic, he fought during the First World War, like his three sons. Commander Lipman was best known as a journalist, contributing to the reviews Faith and Awakening, L’Univers Israélite, Archives Israélites and the Revue Juive de Lorraine. He also participates in the activities of the Alliance Israelite Universelle.

Many refugees settled in the interwar period in the Lille region.

During the occupation in October 1941, 987 Jews were enumerated for the Nord department, the rest having chosen exile. Lille and the North coming under the military government of Brussels, the big roundup took place at the same time as those of Belgium: September 11, 1942. Jews were arrested and taken by train to Mechelen and others parked in camps in work to build the Atlantic Wall from summer 1942 to summer 1944.

Holocaust survivors rebuilt the community after the war. A presence reinforced by the arrival of the Sephardim in the 1960s. Today there are around 3,000 Jews in the Lille region.

‘Apart from Versailles, I didn’t know you could talk about views’, declared Jean Gabin in the movie The Gentleman of Epsom. Versailles is indeed immortalised by its history, its kings and queens, its castle, its works of art and its gardens, as the busloads of tourists testify.

But the town to the south-west of Paris has also been home to a very active Jewish life since the end of the 19th century. A contemporary symbol of this vitality is the fact that the first French edition of Limmud was held in Versailles in 2006.

Although the Jewish presence in the region probably dates back to the Middle Ages, the Versailles community was mainly formed after 1870 when Alsatian Jews, like many other French people, rejected German domination and left Alsace to live in other regions and towns, including Versailles.

Many Jews from Versailles were murdered during the Holocaust. Their involvement in the Resistance was significant. Lola Wasserstrum, for example, distributed anti-Nazi leaflets around the Versailles barracks and was arrested on 31 August 1942. But also Charles Weil and Pierre Feist, fighters in the Black Mountain maquis.

Another famous Versailles Resistance fighter was Dr Paul Weil. Arrested with a group of Franc-Tireur fighters following the destruction of the PPF headquarters in Vichy, he survived deportation and resettled in Versailles after the war, where he continued to practise as a doctor. In 2004, the town council paid tribute to him by erecting a plaque in the vicinity of rue Champ Lagarde, Rond-point Paul Weil . A monument has also been erected in memory of the victims of the Shoah in the Jewish cemetery in Versailles.

It was not until the arrival of the repatriates from North Africa in the 1960s that the Jewish community was able to be reinvigorated, and today consists of several hundred families.

The synagogue

The first synagogue dates back to the Ancien Régime and was located at 9 avenue de Saint-Cloud in Versailles. A larger synagogue became necessary in the 19th century. In 1853, the synagogue opened a new place of worship in part of the former Hôtel du Duc de Richelieu, located next door at 36 avenue de Saint-Cloud.

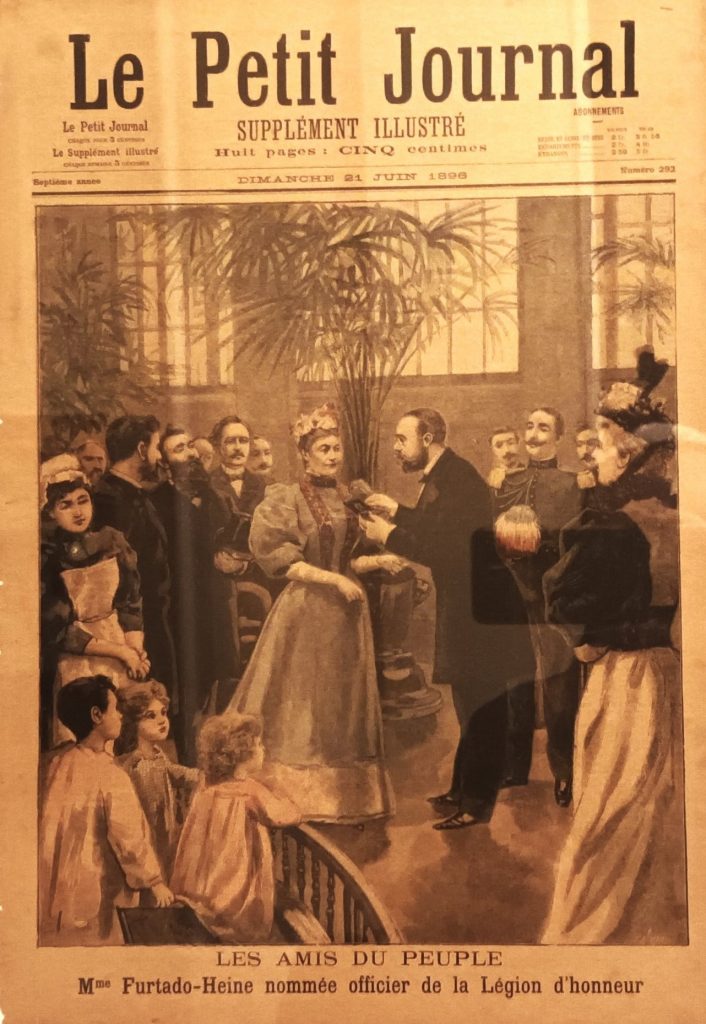

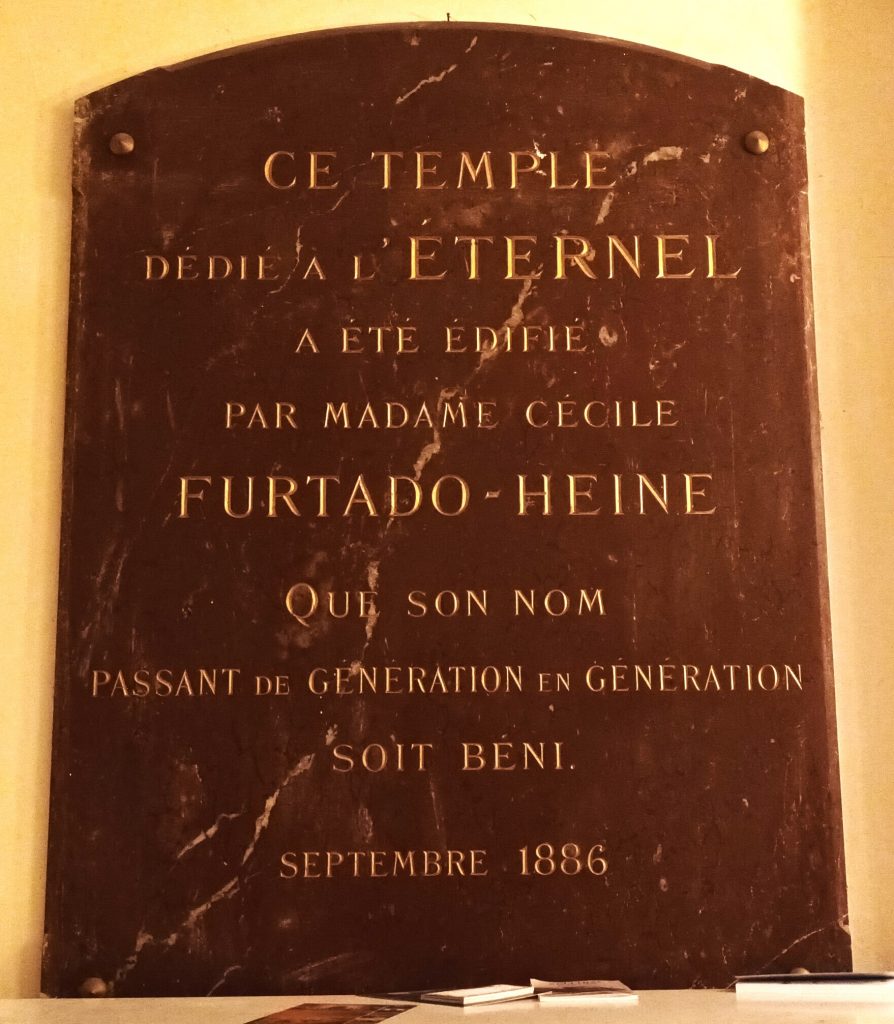

The building was becoming unhealthy and a request was made to the local authorities to build a new Israelite temple on rue Albert Joly. In 1883, thanks to funds provided by Cécile Furtado-Heine (1821-1896), the Israelite Consistory of Paris was able to buy land there. In a letter dated 9 December 1882. Madame Furtado-Heine confirmed her support to the community leader Maurice Cerf: ‘Mr President, I have the honour of informing you that I am placing 200,000 francs at your disposal to build an Israelite temple that I am offering to the Versailles community. I would like the temple to be built with two sacristies, one of which will be used for the usual service and the other as a school for the children. I also want a modest but suitable accommodation for the rabbi and another for the officiant…’.

Cécile Furtado-Heine, along with Daniel Oziris Ifla, helped finance the synagogue on rue Buffault in Paris. She devoted much of her life to philanthropy. In particular, she organised ambulances during the 1870 war, set up a school for young blind people, a dispensary and a nursery in the 16th arrondissement, and a dispensary in Levallois. She also donated funds for a nursery school in Bayonne and gave her villa in Nice to the Ministry of War for conversion into a rest home for officers.

The design of the Versailles synagogue was entrusted to the architect Alfred Aldrophe, the most important Jewish architect of the time. He had also built the Victoire synagogue in Paris, the town hall in the 9th arrondissement and numerous public buildings, schools and orphanages. A man, but also an era that places the synagogue within similar constructions the Victoire, Tournelles and Buffault synagogues, their construction having begun under the Second Empire and completed under the Third Republic.

In 1886, on the occasion of the inauguration of the Versailles synagogue, Chief Rabbi Zadoc Kahn made the following statement: ‘In Versailles, alongside countless masterpieces, it is fitting that the Israelite faith should be able to display without shame the centre of its religious life’. The Versailles synagogue has a very special status, being attached to the Consistoire of France and not to the Consistoire of Paris, as are many synagogues in the suburbs of the capital.

The Versailles synagogue comprises two buildings. The central building contains the synagogue, an oratory for prayers on weekdays (dedicated to the memory of André Elkoubi, who officiated there from 1964 to 1975) and a reception room. Next door is a building with a flat and lounge. There is also an inner courtyard where classes are held, including Talmud Torah on Sundays.

The outside of the synagogue features stained glass windows and a rose window. At the top of the building is a sculpture of unfolded Bible scrolls.

The vestibule of the synagogue is a place of remembrance. Of its donor Cécile Furtado-Heine, but also of the members of the Jewish community who died for France during the First World War, as well as the victims of the Shoah. The vestibule also features a plaque and objects paying tribute to those who played an active part in the development of Jewish life in Versailles.

Inside, the white walls welcome the faithful. The tevah was salvaged from the original synagogue on avenue de Saint-Cloud. Dating from 1853, it is therefore older than the synagogue that houses it today. The tevah was originally imported from Portugal.

Around ten Sifreh Torah are kept in the aron hakodesh. The women pray on the first floor, where one can also see a beautiful organ, donated by the children of Léopold Taub. Dating from the late 19th century, it is used for wedding celebrations.

A special feature of the Versailles synagogue is that every 21 January, the day Louis XVI was executed, a prayer is said in his memory, to remind that he was a benefactor of the community.

Refurbishment work was carried out in 2006 to mark the synagogue’s 120th anniversary. On completion of the restoration work, a book was published by ACIV and designed by Sam Ouazan, Brigitte Levy, Colette Bismuth-Jarrassé and Dominique Jarrassé. With texts by Mayor Etienne Pinte, ACIV President Samuel Sandler, architect Dominique Lecuiller and historians Dominique Jarrassé and Gérard Nahon.

Contemporary Jewish life

Rabbi Arié Tolédano now heads the Versailles Jewish community, which is managed by ACIV, chaired by Maurice Elkaïm. The synagogue lives on donations from the faithful. Services are held here every Saturday morning, with a kiddush offered to participants afterwards.

When Shabbat finishes early on Saturday evenings, film screenings, concerts and other cultural activities are organised. Just over fifty people can attend in the reception room.

But when events need to accommodate more people, they are organised at the cultural centre in Le Chesnay. The same goes for bar mitzvoths and weddings. This centre can accommodate 200 people. The nearest kosher restaurants are in Boulogne, so it is advisable to contact ACIV, which endeavours to find solutions for tourists and students.

The Jewish cemetery at Versailles probably dates back to the time of Louis XVI. It is said that in 1788, while passing near the forest, the King of France came across some Jews burying their dead. Surprised, Louis XVI questioned those close to him. They told him that as Jews were not allowed to bury their own dead in the Versailles cemetery, that was how they managed. It was therefore Louis XVI who decided, following this coincidental encounter, to grant the Jewish community a plot of land measuring 3 perches, or approximately 102 m², located behind the Catholic cemetery of Notre-Dame, now rue des Missionnaires.

In 1821, Louis XVIII granted a plot of land for the current Jewish cemetery in Versailles, located on the Butte de Picardie. The cemetery is located on the Butte de Picardie, more precisely rue des Moulins, which today corresponds to rue du Général Pershing, at number 3. The former Jewish cemetery was taken over by the town after 1834.

A street named after Samuel Sandler was inaugurated on the 6th of November 2024, in Versailles, on the initiative of the mayor of Versailles, François de Mazières, and his municipal councillor Muriel Vaislic. The ceremony was attended by Samuel Sandler’s family and representatives of various faiths.

Samuel Sandler passed away in January 2024 at the age of 77. He worked tirelessly to preserve the memory of the victims of the 2012 Toulouse attacks, in which his son Jonathan Sandler and his grandsons Arié and Gabriel were murdered at the Otzar Hatorah school. Former president of the Consistory of Versailles and administrator of the Central Consistory, he was also an aeronautical engineer and co-authored Souviens-toi de nos enfants (Remember Our Children) (Grasset, 2018) with Emilie Lanez, in memory of those who perished.

Sources: Le Parisien, Times of Israel

A very old Jewish community, Toul has hosted many great religious figures such as the tosafists. Following threats of eviction from the region by religious authorities at the start of the 18th century, around 100 Jewish families were authorized by Duke Leopold to stay.

Léon Cohen, an important figure in local Jewish life, would take part a century later in the General Assembly convened by Napoleon.

The Toul synagogue was built in 1912. There were then nearly 500 Jews in the city. Now disused, architecturally it still testifies even today to that time when Jewish life shone in the region.

A guided tour of the Jewish cemetery of Toul was organised by Jean-Pol Marx, one of the last representatives of the town’s Jewish community. Around thirty members of the Souvenir Français association took part in this cultural outing, coordinated by their president, Maryse Humbert.

Sources: L’Est Républicain

The Jewish presence in Biarritz was very weak until the end of the 19th century. The Jews present are mainly attached to Bayonne for the celebrations of religious festivals and ceremonies. However, the transformation of the fishing town into a renowned summer and spa destination will be a game-changer.

The community of Biarritz really took shape at the end of the 19th century, following a request from brothers Gabriel and Emile Pereyre to the consistory of Bayonne. The beginnings of construction take place from 1896 according to the plans of the architect Charles Pasquier.

The inauguration took place on September 7, 1904. The synagogue is located in a beautiful part of the city, near the Imperial Palace and the Russian Church. It is in the Roman-Byzantine style. With a sober facade, a large rose window, stained-glass windows, and a tebah installed in front of the Hechal.

Following the anti-Semitic act of cutting down the tree planted in memory of Ilan Halimi in Epinay-sur-Seine in August 2025, many town halls decided to plant trees in his memory and to mark their involvement in the fight against anti-Semitism, which has been ravaging Europe since 7 October and the exploitation of conflicts in the Middle East.

Among these town halls is that of Biarritz, where an olive tree was planted on 19 September 2025 in the Square d’Ixelles, following a ceremony at the synagogue attended by elected officials and local authorities.

Sources: Sud-Ouest

If a Jewish presence is mentioned in documents from the Middle Ages, the establishment of a community rather took place at the end of the 18th century. Their presence in neighboring towns such as Foussemagne is older. The emancipation of the Jews of France with the spirit and authority of the French Revolution facilitates their installation.

Thus, from 1791, they mainly lived in the old town. The first birth was celebrated the following year, and the first Jewish marriage a year later. The community numbered 475 Jews in 1823.

A synagogue was built in 1830 and was to be demolished shortly after because it was enclosed in military land. The current synagogue was inaugurated on March 26, 1857 by Salomon Wolf Klein, the chief rabbi of Haut-Rhin.

The synagogue was built by the architect Diogène Poisat Aîné. The facade of the building is in Romano-Byzantine style. It has two pavilions with symmetrical domes and three portals. Inside, the arch is surmounted by a rosette-stained glass window. Floral and arabesque motifs decorate it. The synagogue is listed as a regional heritage for an additional reason: the presence of a mid-19th-century Ungerer clock.

The community grew after 1870 and the arrival of Jews from Alsace. Then, with the arrival of Polish Jews. Of the 700 Jews present before World War II, 245 were murdered. After the war, the community was rebuilt, with the arrival of European Jews and then North Africa.

Belfort also has a Jewish cemetery, which dates from 1811. Visits are organized by the Department of the Territory of Belfort.

A commemorative plaque was unveiled in December 2024 at the Belfort synagogue. This was made possible by the documented work of Nadia Hofnung, in memory of the rabbis and presidents of the Belfort Jewish community since 1791. The historian is also working on the fate of women deported during the Second World War in northern Franche-Comté. The aim is to honour their memory, but also to provide support for teachers.

In 894, a diploma from the King of Provence Louis the Blind in favor of the bishop of Grenoble mentions the Jews. Other administrative documents of the region then refer to it during the Middle Ages, such as a diploma from the king of Burgundy Rodolphe III which mentions vines of “Jewish property” from Viennese.

The Jewish presence is mentioned in Grenoble in the 13th century. A reference to the martyrdom of Jacob ben Solomon, a Jew from Grenoble present in the Burgundian mahzor. Dauphin Humbert I allowed Jews to settle in Grenoble at the beginning of the 14th century, while Philippe le Bel expelled the Jews from France.

However, following numerous accusations and persecutions during this century, especially during the Plague period when conspiracy theories provoked massacres of Jews, they were expelled at the end of the 14th century and did not return to Grenoble until after the Revolution. A community was formed and was subsequently enlarged thanks to the arrival of Jews from Alsace after the war of 1870.

Like Lyon, Grenoble was an important site of the Resistance during the Shoah. The Gestapo was also very active and carried out numerous arrests and deportations of Jews and members of the Resistance.

At a secret meeting in 1943, Isaac Schneersohn helped set up the Center for Contemporary Jewish Documentation, which was responsible for collecting documents on the Shoah, assisted in particular by Leon Poliakov and Jacob Gordin. These documents will prove to be very useful after the war in the trials of Nazis and collaborators, whether it is the Nuremberg trial or the Barbie trial. As the Shoah Memorial indicates, “In another historic trial, that of Klaus Barbie in 1987, it is again the CDJC which provides a major document for the indictment of the head of the Gestapo in Lyon, for crimes against humanity: the Izieu telex. “

In the early 1960s there were nearly 1,000 Jews in Grenoble. A figure which increased considerably thanks to the arrival of Jews from North Africa, reaching 5000 at the end of the decade, then 8000 in 1971. Following the numerous anti-Semitic acts recorded since the beginning of the 21st century, almost half of the Jews are said to have left the city.

Two main Jewish places of worship are present in the city, the Grand synagogue of Grenoble and the Bar Yohaï Synagogue .

Constructed in 1935, the synagogue was built following the installation of Parisian Jews in this pleasant suburb crossed by La Marne. Eminent rabbis such as Jacob Kaplan, Jean Kling, Meyer Jaïs and Jacob Madar officiate there.

The distribution of places in the synagogue is quite classic. A vestibule precedes a nave. The sanctuary is marked by an apse. The reception of men on the ground floor and women on the first floor. An oratory for men and a reception hall are present in the synagogue.

If the interior, with its curved bays with colored stained glass windows, is fairly sober, the facade is more impressive. The Star of David fits a rose, beneath which are the Ten Commandments. The bimah is located next to the holy ark. The Leviticus message “You will love your neighbor as yourself” is written in large, in Hebrew and French, on the wall facing the balcony.

Jews living in Neuilly since the mid-19th century organized a small oratory on rue Louis-Philippe in 1869. 140 Jews were identified in the community in 1872.

Following the purchase of land, in particular thanks to the philanthropist Godchaux Oulry, rue Jacques-Dulud in 1875, the architect Emile Ulmann, Grand Prix of Rome, takes the works in hand.

The synagogue was inaugurated in 1878. A neo-oriental-style building. With two pavilions on which are carved the tables of the Law.

On the central arch is inscribed the passage of the Psalms “Open the doors of salvation to me, I want to cross them, pay homage to the Lord”. Inside, the Byzantine references are quite present. The bimah precedes the holy ark.

The first rabbi is Simon Debré, patriarch of the famous family involved in French public life. Among the other rabbis, the one who succeeded him, Robert Meyers deported and killed in Auschwitz, Jérôme Cahen, very involved in youth projects, and Michaël Azoulay, who enabled great progress to be made in the place of women in active religious life.

Structural and decorative modifications were made from 1936 to 1937 in the synagogue following its expansion encouraged by the growth of the Jewish community of Neuilly, which numbered 6,000 faithful. The architects Germain Debré and Julien Hirsch are leading this project. An entry is added rue Ancelle. The artistic influences are more modern. Thus, the round shapes are added to the square ones of the old construction. Maguen David and tables of the Law adorn the top of the facade.

Following the creation in 1999 of the European Jewish University by rabbis René-Samuel Sirat and Claude Sultan, the Jérôme Cahen cultural center was created in the adjoining building of the synagogue.

In 2010, following the centenary celebrations of the Vincennes – Saint-Mandé synagogue, a book written by Dominique Jarrassé, with the participation of Elie Zajac, was published as a tribute to this beautiful synagogue and its fraternal spirit.

Laurent Lafont, mayor of Vincennes, and Patrick Baudouin, mayor of Saint-Mandé, wrote moving texts at the beginning of the book, recalling the golden age of synagogues, their evolution over time and, above all, the spirit of the French Republic to which the local Jewish community and its shared values have borne witness for a century.

The preface is written by Bruno Blum, president of the Ashkenazi synagogue, and Dov Houri, president of the Sephardic synagogue. “Not so surprising, given the spirit of the Vincennes – Saint-Mandé synagogue, which for decades has brought together Jews from both the former Ashkenazi communities of Alsace-Lorraine, Eastern Europe and those of North Africa. The synagogue has several prayer rooms, each of which respects a particular rite, and above all shares an open and generous perception of Judaism.

In 1872, a census showed that there were 108 Jews in Vincennes and 84 in Saint-Mandé. To these were added a handful of Jews from Montreuil, forming the first Jewish community in Vincennes – Saint-Mandé. Before they had a synagogue, they prayed in an oratory created by Rabbi Maurice Zeitlin and located at 21 avenue Gambetta in Saint-Mandé.

Arthur Willard, born in Ingwiller in 1873, was the first rabbi to be appointed head of the Saint-Mandé community in 1902. A plot of land was purchased for the construction of the synagogue , with donations from the faithful and the help of the Consistoire. The land on which the synagogue was built was donated by the great patron Daniel Iffla, known as Osiris.

Born in Bordeaux in 1825, Osiris came from a modest family. He moved to Paris to work in finance, where he enjoyed great success. In the 1860s, he decided to devote himself fully to philanthropy, patronage and art. In this spirit of generosity and patriotism, he helped build the Buffault synagogue in Paris, as well as an operating room for women at the Pitié-Salpêtrière hospital, a serotherapy institute in Nancy and a soup boat in Bordeaux to feed the poor. Osiris also ensured that the Pasteur Institute would be his universal legatee.

It was not until 5 September 1907 that the Vincennes – Saint-Mandé synagogue, designed by architect Victor Tondu, was officially inaugurated. The mosaic pavement in front of the bimah bears the inscription ‘Tishri 5668’, in reference to the Jewish new year that saw the inauguration of the synagogue. This was also the year in which Osiris died, in February 1927. In his speech, Chief Rabbi Dreyfus paid tribute to the patron of the arts. He recalled his patriotism, his commitment and his generosity.

The rite practised in the synagogue at the time was Alsatian, in keeping with the fact that many of the Jews living in Saint-Mandé and Vincennes were originally from Alsace. Between the wars, many Jewish families from Eastern Europe settled in the area, mainly from Poland, Russia, Romania and Hungary. This enabled the communities in the eastern suburbs of Paris to grow. Montreuil and Bagnolet in particular. It is estimated that nearly 1,000 Jews were living in Vincennes in 1936. At that time, Russo-Polish Jews made up around a third of the Jews living in Vincennes. As a sign of this demographic change, in 1938 Wolf Gordon became President of the Community. A shoemaker in Russia and even the Tsar’s bootmaker, he had arrived in France in 1906, following the pogroms.

German troops entered Vincennes on 14 June 1940. Of the 874 deportees from Montreuil, Bagnolet and Vincennes, only 27 survived the Shoah. Many of these victims were children, as the commemorative plaques erected much later would remind us.

In the aftermath of the war, the Jewish community of Vincennes – Saint-Mandé gradually rebuilt itself. Not least thanks to the arrival of Jews from North Africa in the 1950s. This influx accelerated following Algeria’s independence. By the end of 1962, 150 families had settled in Vincennes. In 1959, the Marouani brothers brought together the first faithful who arrived in a small room adjoining the Ashkenazi synagogue. Around forty people attended the services, which were led by brothers Alain and Michel Chetboun.

Joseph Guez took over the leadership of the community. The Ashkenazim and the Vincennes town council were very active in helping these new arrivals. In 1967, for example, when Jules Schick was informed of the financial problems involved in Joseph Guez’s attempt to organise a holiday camp for recently arrived Sephardic children, he immediately covered the necessary costs.

This very fraternal spirit was also put into practice in another way when, in 1965, the ‘Hatikvah’ youth association was created, uniting Ashkenazim and Sephardim.

As the number of worshippers grew, the Sephardic building was extended in 1965, again in 1975 and again in 1982. Numerous projects were studied with a view to building a viable Sephardic synagogue right next to the Ashkenazi synagogue.

In 2000, architect Jacques Emsallem applied for permission to extend the synagogue. When planning permission was granted, an opportunity arose to purchase the Bardoux warehouses opposite the synagogue. The purchase of these premises turned out to be less expensive than a major architectural modification to the synagogue, and represented a gain in surface area. The community therefore bought the premises and carried out less extensive work on the synagogue. Prayers were held in the room while the synagogue is being refurbished, and the room later became a community centre. Its representatives Paul Fitoussi and Léo Touitou were very involved in this project.

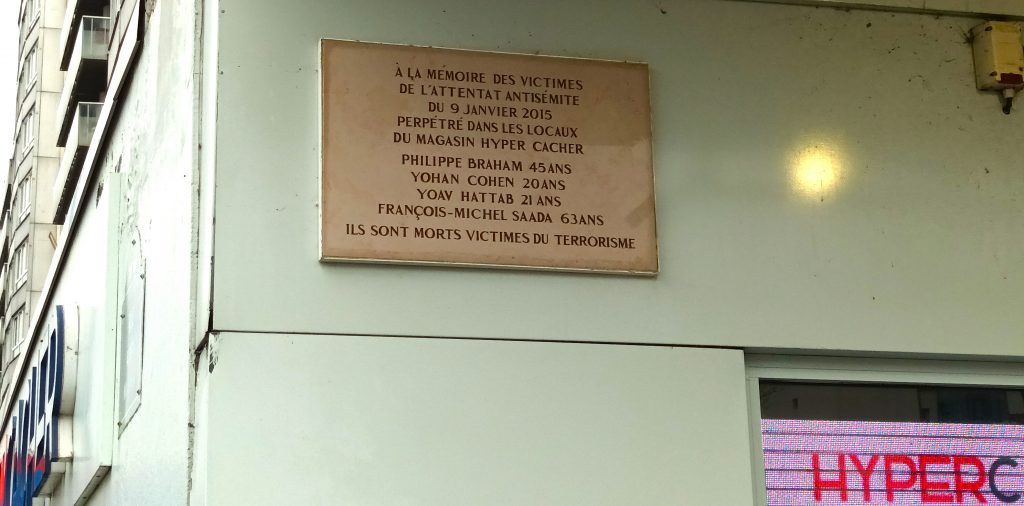

On 7 January 2015, the Charlie Hebdo staff and policemen protecting them fell victim to a terrorist attack. The next day, a policewoman was also murdered by a terrorist in Montrouge. On 9 January, that same terrorist killed four Jews held hostage in the Hypercacher supermarket at Porte de Vincennes.

In 2025, the two rabbis of the Ashkenazi and Sephardic synagogues are Joseph Assayag and Hay Krief respectively. The various minhagim, prayer tunes and traditions are explained and shared in the same fraternal spirit. These are two very lively communities, where shabbats, festivals and numerous religious and cultural activities are organised on a regular basis. The Ashkenazi synagogue in Vincennes-Saint-Mandé is currently the only one in the outskirts of Paris to follow this rite.

A dozen other small places of worship also exist in Vincennes-Saint-Mandé. And as Dominique Jarrassé and Elie Zajac point out in their book, these Jews from Alsace, Russia, Poland, Turkey and North Africa blend harmoniously as ‘tsarfatim’, French of Jewish faith.

This text was written with the help of Rabbi Joseph Assayag and Élie Lobel.

The Boulogne synagogue is located on the eccentric part of rue des Abondances, not far from the Maimonides school.

It was built in 1911, according to plans by architect Emmanuel Pontremoli. Its geometric shape is particularly original, responding to the tastes of the time of its creation.

The Byzantine references of the synagogue are close to those of the Chasseloup-Laubat synagogue. The painter Gustave-Louis Jaulmes decorated the grounds. We notice the strong presence of light in this soothing setting.

Nearby, the Albert Kahn Departmental Museum . Born thanks to the ambition of the Jewish philanthropist of the same name, he wanted to bring together vegetation from all over the world. These “Archives of the Planet” were collected for more than two decades, from 1909 to 1931.

In a world which lived a war and which ran to its next one. Additional motivation for Albert Kahn to allow the exemplary coexistence of the world’s vegetation, while the man persisted in his murderous madness.

Among its treasures, visitors are particularly attracted to the Japanese Garden. Cherry blossoms, bridge, stream and serenity guaranteed.

Continue your walk to discover the English and French gardens, then the Colorado spruces or the Atlas cedars. The Albert Kahn Gardens constitute a veritable natural amusement park.

Nice is known as one of the jewels of the Côte d’Azur, with its long promenade, old town, architecture and colorful mix of Italian and French beauty.

The Jewish presence in Nice probably dates from the Greek era. The successive occupations, mainly linked to the conflicts between France and Italy, affected the status of the Jews over the centuries.

A Jewish presence is identified in the middle of the 14th century. Nice then depended on Provence, and the Jews were forced to wear a distinctive sign.

In 1406, the Jewish community had official status, while the city once again belonged to Savoy. Two years later, she has a cemetery near Lympia harbor. A synagogue was erected twenty years later. The Duke of Savoy, while imposing restrictions on housing and profession, protected the Jews from the imposed conversions.

From 1448, the Jews had to settle in a Giuderia, a separate district in the city, in accordance with the directive of the Pope. However, there is an evolution in their social and economic situation.

In 1499, Nice welcomed Jews expelled from Rhodes and other places in the Mediterranean basin, following the Inquisition. In the 16th century, Jews were allowed to practice commercial trades and medicine, motivating in particular the arrival of these Jews.

The Jewish community grew with the arrival of Marrano Jews from Italy and the Netherlands in the mid-17th century.

The Duke of Savoy encouraged the prosperity of the whole city and, in particular, of the Jews by decreeing the establishment of a free port in Ville Franche. Oran Jews also settled in the city at the end of the century.

From 1723, the Jews were all forced by Victor Amédée, king of Sardinia, to settle in the old ghetto, the practice having been relaxed before. Rare derogations are obtained.

At the end of the 18th century, Duke Charles Emmanuel III relaxed the status of the Jews, allowing them to leave the ghetto, buy land around the port, and no longer wear a distinctive sign. In this impulse, the Jews obtained the right to organize a community council in 1761.

The attachment of the city to France between 1792 and 1814 resulted in the emancipation of the Jews, as was the case for all nationals since the years 1789 (date of the Revolution) and 1791 (decree promulgating equality for the Jews).

When the region was attached to Sardinia in 1828, these rights were canceled. It was not until 1848 that emancipation was final, with the suppression of the ghetto.

King Charles Albert then recognized the Jews’ absolute equality of rights as citizens. An evolution favored by the dedication of Benoit Bunico, city councilor. When he died, rue de la Guidaria was renamed rue Benoit Bunico. The Edict of 1430 is therefore definitively repealed.

Despite these developments, the number of Jews from Nice was relatively very low throughout the 19th century. In 1808, they made up only 300 souls.

In 1909, a hundred years later, that number of Jews living in Nice only increased by 200 people.

Many Jews settled in the city after the start of the 20th century. Among them, the writer Romain Gary. “It was at the age of thirteen, I believe, that I had the first feeling of my vocation. I was then a fourth-year pupil at the lycée de Nice and my mother had one of these hallway “showcases” at the Hôtel Negresco where she displayed the items that luxury stores conceded to her… ”At the start of Promise at Dawn, the author relates the arrival in France of the family and the devotion of his mother to make them survive, pretending not to like meat so that his son has enough. His only comfort was his success in becoming a Frenchman proud of his homeland and a great man of letters, dazzled by the reading of his childhood poems. “You will be d’Annunzio! You will be Victor Hugo, Nobel Prize winner!” Romain Gary will keep his attachment to the city and to the commitment to the homeland. As he recounts a few pages later during military service. He returned to service a few years later when he joined Charles De Gaulle.

When Nice was free and then fell under Italian control during the Second World War, thousands of Jews found refuge there. When German troops took possession of the city in 1943, the situation changed abruptly. In five months, 5,000 Jews arrested and deported. The evolution of this situation is well described by Joseph Joffo in his book A Bag of marbles. The Joffo family, who lived in the 18th arrondissement of Paris, ended up in Nice to escape the raids. Joseph and his brother Maurice, arrested by the Gestapo, are saved by the priest of Nice who testifies in their favor, producing baptismal certificates.

After the Liberation, hundreds of Jews from Nice began to rebuild the community. The arrival of Jews from North Africa in the 1960s increased their number to 20,000. Today the number of Jews from Nice is estimated to be less than 10,000.

Today there are a dozen synagogues or prayer rooms in Nice. In the neo-Byzantine style, the Great Synagogue of Nice , built by the architect Paul Martin, was inaugurated in 1886. There is a pyramidal stone facade with a central rose window. It has beautiful interior decorations including twelve stained glass windows with biblical themes.

The Ezrat Ahim Synagogue follows an Ashkenazi rite. It was opened in 1930 and has interesting interior architecture.

The Maayane Or Synagogue of the Massorti movement was opened in 1996. It also has a large cultural and community space, with a Talmud Torah, Hebrew lessons, religious festivals and other activities.

The Jewish cemetery is located in the Castle Cemetery created in 1783, in its southern part. A cenotaph has been installed at the entrance to the cemetery for Nice victims of the Shoah.

Unmissable place to visit in Nice: The Marc Chagall Museum . A museum which is the fruit of the wish of the Minister of Culture André Malraux in 1969. The artist participates in the development of the project. He creates and donates works for the Museum and participates in the inaugurations of exhibitions. Without limiting his support for painting, Chagall launched a concert policy there. When he died in 1985, the Museum received 300 works by Marc Chagall. The artist’s heirs then continue donating to the museum.

In September 2024, a plaque in memory of the hidden Jewish children of the Sainte-Claire Monastery was unveiled in the presence of the Mayor of Nice, Christian Estrosi. These children were saved from deportation thanks to the courage of the Poor Clare Sisters, three of whom were recognised as Righteous Among the Nations. This was achieved with the help of the Marcel Network led by Odette Rosenstock and Moussa Abadi. In total, the network managed to hide 527 children, including around a hundred who were hidden in the Sainte-Claire Monastery.

An important city in the Champagne region, Troyes’ old town is shaped like a Champagne cork. With its renowned gastronomy accompanying its beverages, its many buildings protected as historic monuments, its Gothic cathedral and its churches and museums overlooking the Seine. Troyes is also famous in modern times for its textile industry, which flourished in the 19th century, particularly in the hosiery sector. Among the major brands created in Troyes are Lacoste, Petit Bateau and Dim.

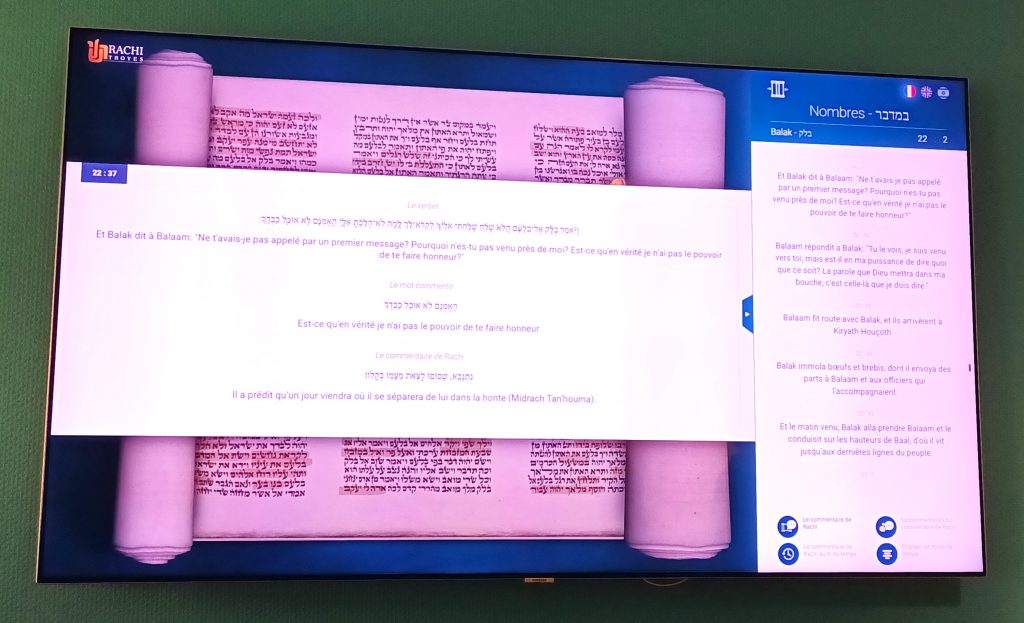

The Jewish presence in Troyes probably dates back to the 10th century, at least according to documented archives. A few hundred people were present the next century. throughout the next centuries, the town has remained one of the most important centres of Jewish study of all time, thanks in particular to the immense Rachi de Troyes (his name being written RACHI in French and RASHI in English, we’ll use the original French form in this text), whose memory is honoured by the town and shared by the two places that face each other on the two banks of the rue Bunneval, the Institut universitaire et culturel européen Rachi (Rachi European University and Cultural Institute) and the Maison Rachi (Rachi House), linking the past and the future.

Rachi of Troyes

When you open the five books of the Torah, the Talmud or many other religious works, a word, or rather a name, accompanies your approach to these texts: Rachi. While various sources of commentaries on texts that have been shared for thousands of years can shed light on a particular point, situation or character, Rachi is unanimously recognised as the supreme reference. His ability to provide a link between the biblical texts and all the commentaries he has selected, comparing the most relevant approaches to the most complex questions. He makes reading easier by identifying the literal meaning, the pshat.

A national pride, Rabbi Shlomo Itshaqi, better known as Rachi, was born in the French town of Troyes in 1040. He received excellent rabbinical training from the rabbis Jacob b. Yakar, Isaac b. Judah in Mainz and Isaac b. Eleazar Ha-Levi in Worms, he resettled in Troyes and opened his own study centre. Between eastern France and western Germany stood an economically and intellectually prosperous region, encouraging exchanges on both levels.

As his pupils did not pay for their lessons at the time, the teachers were obliged to support themselves. Thus, since Rachi’s texts include numerous references to working in the vineyard, suppositions began to be put forward about his activity as a winemaker.

Rachi represents the junction of traditional excellence and modernism. As a leading intellectual figure, but also in his involvement in the community, he gave pride of place to the French language in his interpretations. Rabbi Claude Sultan, who directed the Rachi Institute, claimed that French linguists studied his biblical commentaries to discover French words from the Middle Ages. Rachi’s commentaries were not intended for the international audience that has been reading them since the development of printing a few centuries later. At the time, they were mainly clarifications intended for the communities of Champagne, where the langue d’oïl was spoken. When people didn’t understand a word, Rachi would write it down in the Champenese language, adding it to his text alongside the Hebrew terms. This was known as the laazim. Hence the great interest shown by linguists and philologists in these texts.

Christian religious texts, such as those of Nicolas de Lyre, also refer to them. Exchanges between Jewish and Christian thinkers were regular and warm. In Rachi’s time, but also in that of his descendants. His descendants, starting with his three daughters, Miriam, Yokhebed and Rachel, who carried on his teaching. Then, with the creation of the school of Tossafists. Among them were Rabbis Rashbam, Ribam and Rabenou Tam. This school spread throughout the region to Ramerupt, Dampierre and Sens.