Ferrara, a sublime city with a medieval centre listed as a World Heritage Site, does not appear to be a vast, museum-like enclosure encircled by a city. On the contrary, its historic centre is delicately interlaced with long, beautiful streets leading to monuments and a gentle way of life that is far from fleeting and to which its inhabitants cling, as did, despite everything, the characters in Vittorio de Sica’s film The Garden of the Finzi Contini (1970)…

History of the Jews of Ferrara

The Jewish presence in Ferrara dates back to at least the 13th century, when the city welcomed Jews from other Italian and European cities. This presence was formalised in 1287 by an ordinance. As long as it remained the capital of the Dukes of Este until 1598, Ferrara was one of the great centres of Italian and European Judaism, with over 2,000 Jews for 30,000 inhabitants during its golden age, between the 15th and 16th centuries. This was also a period in history when many artists and writers also found refuge here.

A synagogue was built in 1481. A synod of the rabbis of Italy was held in Ferrara in 1534. Ashkenazim from Germany and Sephardim welcomed after their expulsion from Spain lived side by side under the protection of the local authorities.

The corso della Giovecca, the main street linking medieval and Renaissance Ferrara, bears witness to this happy past. Prestigious rabbis and doctors lived in the city, which, like Bologna, was a centre of Jewish printing. Abraham Usque published the famous Ferrara Bible here in 1555.

Things came to a head in 1597 when Duke Alfonso d’Este died without a male heir. The Papacy took control of the city, which had been abandoned by the d’Este court, who, like many Jews, left for Modena. The ghetto was established in 1627.

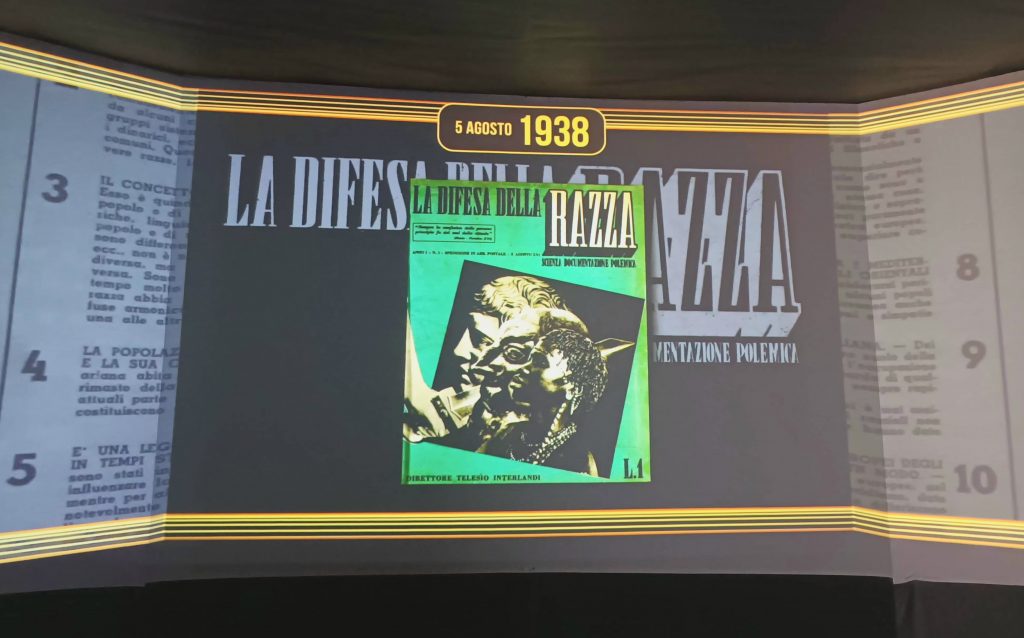

Despite the difficulties, and even after emancipation (1859), the Jews remained fairly numerous in the city, until the racial laws imposed by Mussolini in 1938. This tragedy was admirably recounted by the writer Giorgio Bassani, who devoted most of his books to Jewish Ferrara. Nearly 200 Jews were arrested and deported to the camps from 1943 onwards. The fascists destroyed a synagogue and other community property. Following the Liberation, a small Jewish community was reborn and, since 2017, has been home to the National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah (MEIS) .

Visiting Ferrara

The MEIS can be reached from the station by taking Via Pavia. On the way, you’ll see the city’s football stadium on the left and the Aqueduct on the right, where there is a statue of a man pouring water over children, a city caring for its new generations. This is also the site of the family assistance centre.

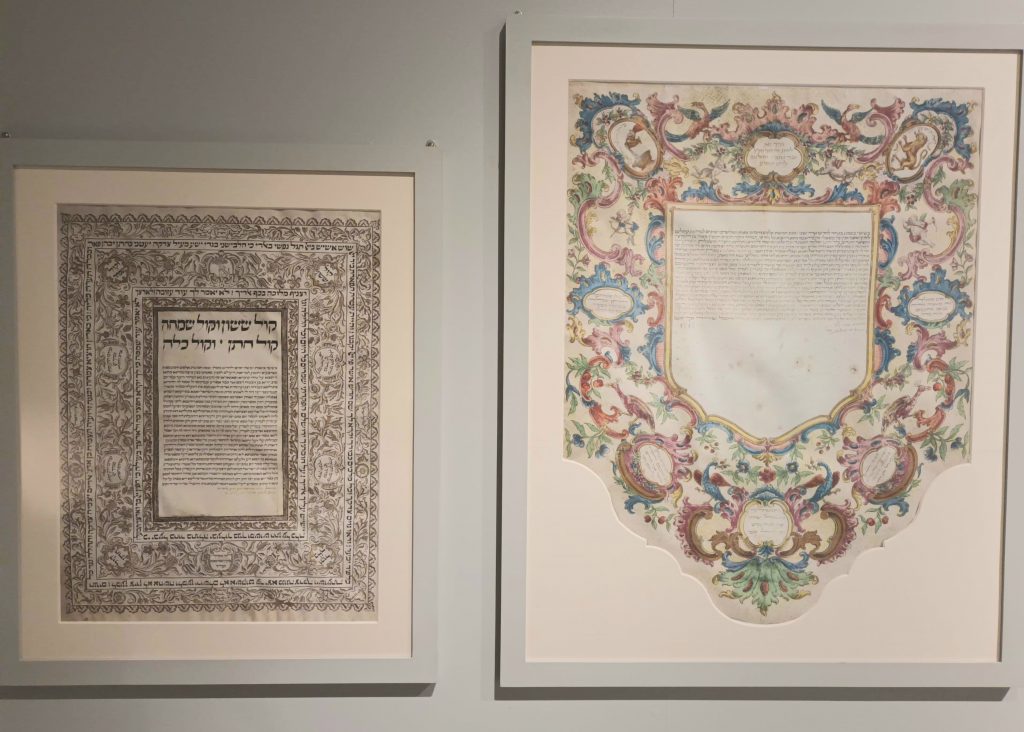

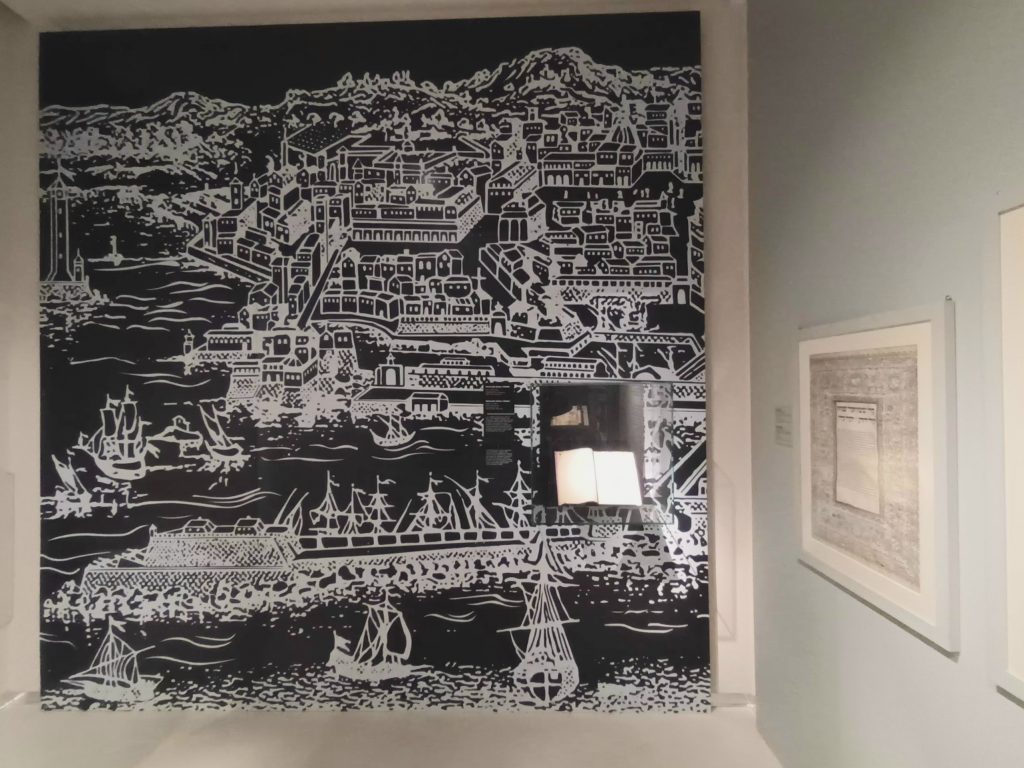

The permanent exhibition is housed in the MEIS interior building, separated by a park, and the temporary exhibition in the building located at the front of the complex. The permanent exhibition is devoted to Italian Judaism from Antiquity to the Renaissance.

Antiques, panels, reproductions and videos by specialists harmoniously accompany this itinerary. It’s a collection that’s much appreciated by young people in particular. When we revisited the museum in 2024, we witnessed a class of schoolchildren from Ferrara enthusiastically following this itinerary.

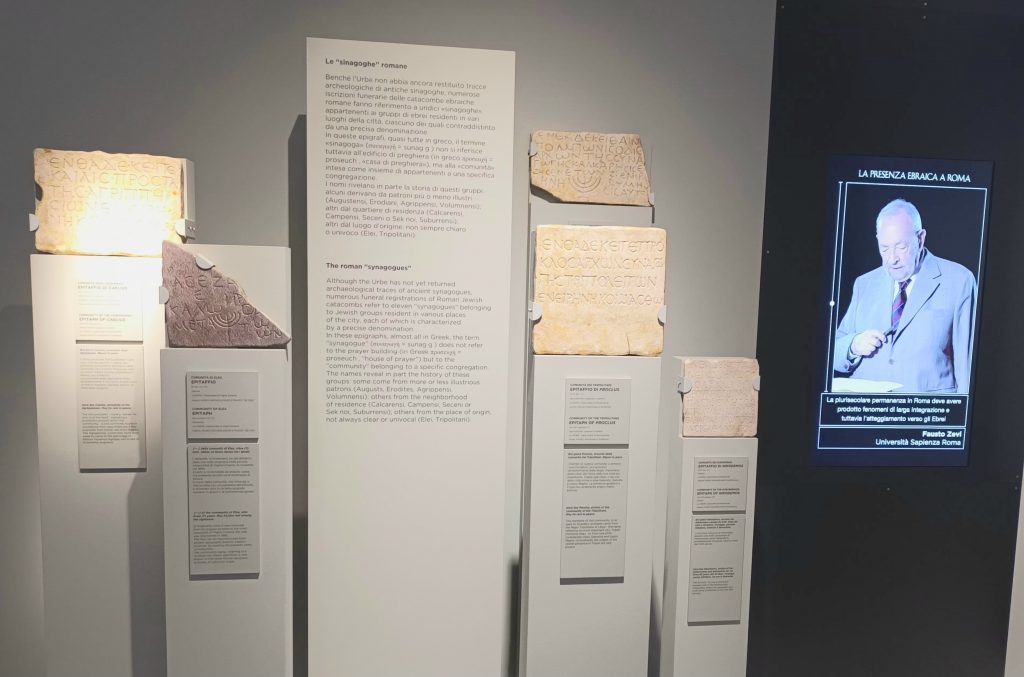

Like the Jewish Museum in Bologna, the tour begins with a general presentation of Judaism. First, we discover the oldest traces, then we come to the Revolt of 70 in Israel against the Romans, with the reproduction of the famous engraving of the Arch of Titus. You will also discover the ancient synagogue of Ostia.

The signs indicate that the Jews have been Roman citizens since 212, thanks to the Edict of Caracalla, like all the other minorities. Seneca and other intellectuals gave them a somewhat lukewarm reception, not understanding the “usefulness” of Jewish customs, particularly the day of rest, which they considered to be idle.

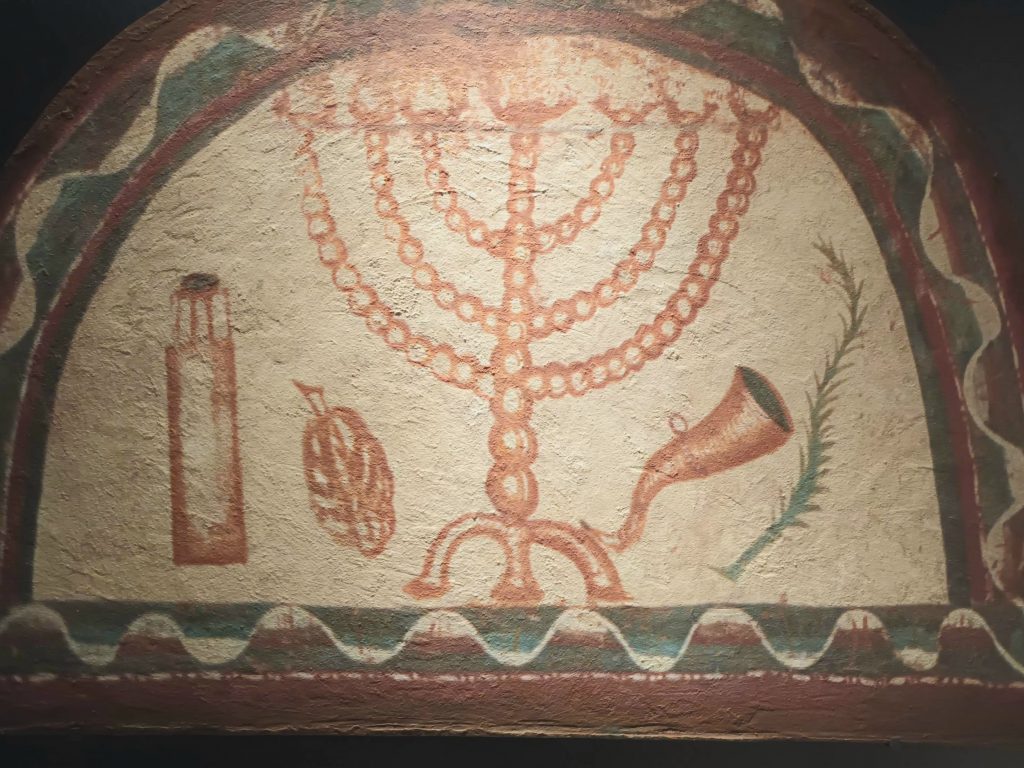

Next, we see the ancient catacombs with a drawing of a menorah dating from the 2nd or 3rd century and found by accident in 1859 in via Antiqua. Then, a mosaic from southern Italy. From 313 onwards, the situation worsened for the Jews, particularly when Constantine promulgated very harsh laws banning Jewish-non-Jewish couples. Nevertheless, the practice of Judaism remained free.

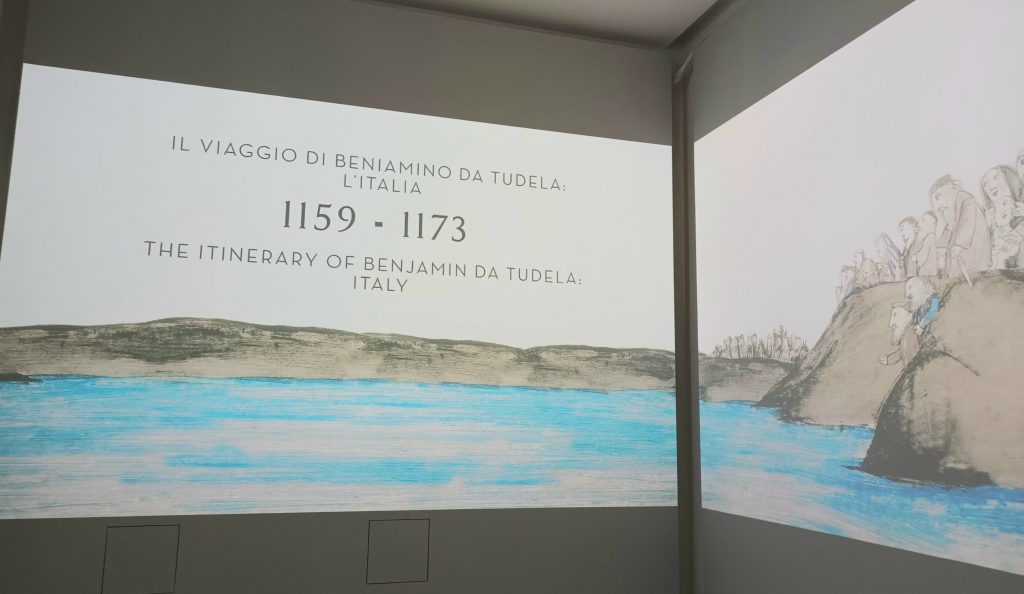

A film is then projected onto the walls of a room, recounting the famous 12th century voyage of Benjamin of Tudela aiming to discover the variety of European Judaism. With images on three walls simultaneously.

Following the decline of Rome and the Inquisition, we discover the migration of Italian Jews to other regions, particularly to the north. From the 14th to the 16th century, the attitude of political and religious leaders varied. During this period, ghettos were established, starting with Venice in 1516. The museum highlights the exceptions of Pisa and Livorno, which never built ghettos to confine Jews. Duke Ferdinand de Medici invited the Jews to settle and work there freely. They were able to enjoy freedom of worship, protected from the Inquisition.

The permanent exhibition therefore stops at this period. Museum officials told us that the MEIS was preparing the continuation of the permanent exhibition, from the Renaissance to the present day.

Leaving the museum, turn right into Via Piangipane, then left into Via Boccacanale di Santo Stefano and second right into the beautiful Via delle Volte where you’ll admire, as its name suggests, a multitude of vaulted elevated passages.

At the end of Via delle Volte, turn left onto Via delle Scienze, where you will find the Biblioteca Ariostea . This library holds many manuscripts, books and engravings on Jewish Ferrara.

Continuing north along this street, take the first turning on the left into Via Giuseppe Mazzini. At number 95, you’ll see Ferrara’s old synagogue . The magnificent scola tedesca is currently only used for major ceremonies. The prayer room is lit by five large windows overlooking the courtyard. The opposite wall is decorated with beautiful medallions and stucco depicting allegorical scenes from Leviticus.

At the top of another staircase and a long gallery is the elegant room of the scola italiana, which is no longer used for worship. On the far wall are three precious aronot in lacquered wood with elaborate carvings. The one in the centre, all gold and ivory, belonged to the scola italiana, while the other two, blue-green, each with two magnificent twisted columns, come from the old scola spagnola in via Vittoria. Furniture from the rabbinical academy has been placed in the vestibule.

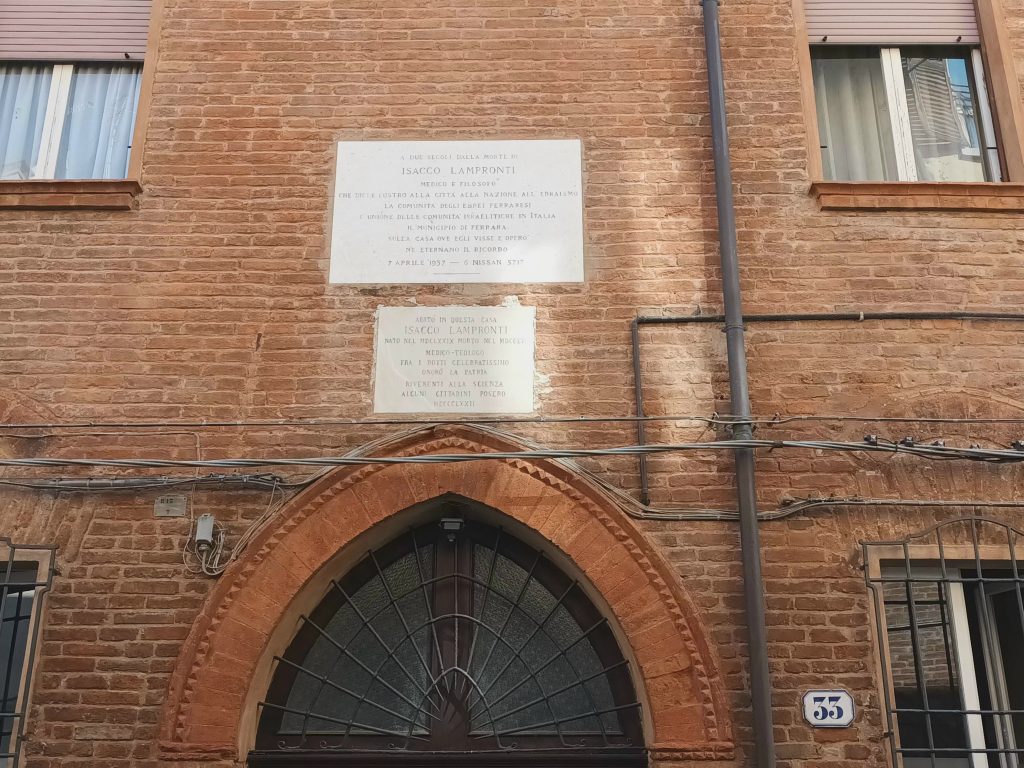

A little further along Via Mazzini, turn left into Via Vignatagliata, one of the main streets of the former Jewish ghetto . At number 33 is the house of Isacco Lampronti, a doctor, philosopher and important representative of the community.

The Jewish school was located at number 81 on the same street, with its many pretty orange houses.

A small square bears the name of Lampronti, between Via Vittaglia and Via della Vittoria, one of the other main streets in the Ferrara ghetto.

Leaving the ghetto, follow Via Ragno to Corso Porta Reno, which leads to the lovely Piazza Trento-Trieste, dominated by Ferrara Cathedral and the Torre della Vittoria. Between them lies the handsome Palazzo Municipale, the whole forming a spiritual and temporal city centre ensemble, as in many Italian cities in the region.

Numerous tributes in the form of plaques are placed on the municipal buildings and palaces surrounding the cathedral, in memory of people from different eras who fought for freedom.

A little further up Corso Porta Reno, you come to the castle surrounded by pools of water, making you wonder which one is protecting the other.

If you go around the castle to the left, you will come to Corso Ercole d’Este. This leads to the Museum of the Resistance, the location of the Finzi-Contini film set and the famous Palazzo dei Diamanti, so named because of its unique architecture. It hosts some very fine exhibitions.

A little further on, turn left onto Via Arianuova towards the small Levantine Jewish cemetery , a trace of Ferrara’s former Sephardic presence. It is located on the small Via Gianfranco Rossi between a few houses and a car park, next to a school where a plaque in honour of a teacher deported to Buchenwald can be seen on the outside wall. The cemetery is currently closed to the public.

To get to the main Jewish cemetery , you can walk through the pretty Massari Park, which may remind you of the great actress Lea Massari, although this is a much older tribute. While there is a café called Central Park, it is unlikely that this park will be twinned with the one in Manhattan.

But it’s a pleasant place to stroll, to salute the statues of Verdi and Dante and to admire the 2015 fresco dedicated to the 70th anniversary of the Liberation of Ferrara.

Leaving the park, take Corso Porta Mare. Then, in Via delle Vigne, you come to the Cimetero Ebraico, in use since 1620, in front of its large entrance gate with Hebrew inscriptions. The cemetery is mainly open to the public in the morning.

After this long day, you can enjoy the beautiful Piazza Ludovico Ariosto, choosing to sit on the stone benches that surround it or at the café under the arcades that will remind you of Bologna.

Interview

MEIS was a challenge from the moment it was built: to transform a place of confinement into an open and inclusive space. Meet Rachel Silvera, Director of Communications at MEIS, who tells us about this important place in Italian Jewish cultural heritage and the many projects it organizes.

Jguideeurope : Can you present us some of the objects shown at the permanent exhibition dedicated to Jewish Italian history?

Rachel Silvera : In our permanent exhibition “Jews, an Italian Story” we display objects loaned by other Italian museums, reconstructions, and multimedia installations. For example, our visitors can admire the relief from the Arch of Titus showing the spoils of the Temple, a plaster reproduction made in 1930. The relief depicts the triumphal procession of Titus in Rome after the military campaign in Judaea, parading the spoils looted from the Temple of Jerusalem. You can also find the reconstructions of Jewish Catacombs, in Rome (like Villa Torlonia and Vigna Randanini) and in the South of Italy (Venosa).

How do you perceive the evolution of interest in Shoah studies in Italy?

It is a fundamental way: 1) to know the history and strengthen awareness 2) to offer useful tools to the students and transmit values to the next generation 3) to fight Holocaust denial and distortion.

Which educational projects focusing on the Shoah are being conducted by the Museum?

During the pandemic we have organized two important online events for school students devoted to the Shoah and the future of the remembrance. We have reached more than 12.000 students. Every year we also offer an online course addressed to teachers focused on Shoah history and the relationship with new medias. We are working also on a project financed by the Ministry of Public Education along with a high school from Ferrara (Liceo Roiti) and the Institut of Contemporary History of Ferrara: the students are working with us to create an exhibition focused on the Racial Laws and the persecution.

Can you tell us about a moving encounter at the Museum with either a visitor or exhibition participants?

The Museo Nazionale dell’Ebraismo Italiano e della Shoah (National Museum of Italian Judaism and the Shoah) is in Ferrara, in the former prisons of via Piangipane. During the war, its walls imprisoned antifascist opponents and Jews, including the writer Giorgio Bassani, Matilde Bassani and Corrado Israel De Benedetti. The challenge was to transform a place of confinement into an open, inclusive space.

During the last International Holocaust Remembrance Day, we unveiled a commemorative plaque that remember the story of this place. The special guest was Patrizio Bianchi, the Italian Minister of Education. It was a really touching moment.