The history of Vienna’s Jewish community can be divided into several distinct periods, with the community itself settling in two specific neighborhoods: in a section of the city center in the First Bezirk and in Leopoldstadt in the Second Bezirk.

In the Middle Ages, the first Jewish community in Vienna established itself in what came to be known as the “Judenstadt” in the heart of the city not far from the cathedral, inside a perimeter roughly delimited by present-day Seitenstettengasse, Hoher Markt, Jordangasse, and Judenplatz.

The Gothic-style synagogue, similar to the Alteuschul in Prague, was first mentioned in 1294 as the Schulhof, named after the spot on which it was built (now the Judenplatz) in immediate proximity to the Court.

In addition to the Judenplatz, there is a nearby different square called Schulhof, bordered by a Gothic church resembling the former synagogue and perhaps an exact replica of it, designed after its destruction in 1421. Between 1360 and 1400 the Jewish community ranged from 800 to 900 people, representing 5% of Vienna’s total population. In 1421, however, they were all either expelled or forced to convert.

In 1624, the Jews were granted a new neighborhood, the Unter Werd, located along Taborstrasse in present-day Leopoldstadt, on the other side of the Danube. A new syngogue was built there; Leopoldskirche church stands on the site today. The Unter Werd ghetto, which included 132 houses, offered the Jews a certain amount of protection until it was destroyed and its residents exiled in 1670.

Beginning in 1781, with Joseph II’s edict of tolerance, Jews settled in Vienna once more. In 1826, a new synagogue by architect Josef Kornhäusl was built on Seitenstettengasse, marking the community’s effective return to its historical center of Jewish life of the Middle Ages. In 1858, another synagogue, the Leopoldstädter Temple, was built across the Danube not far from where the former Unter Werd ghetto once stood in Vienna. This attracted Jewish settlers to the district, later called Mazzesinsel, or “Matzoh Island”.

Here and there along its streets, you will come across plaques marking former Jewish community establishments. The Leopoldstädter Tempel stood on the street bearing the name Tempelgasse, at number 5.

A plaque a four large columns by architect Martin Kohlbauer evoke the former synagogue. In its place today is the ESRA , a center dedicated to counseling the victims and witnesses of the Shoah and uprooting.

At number 7 on the same street sits the Sephardic Center , which brings together associations of Jews from Bukhara, Georgia, and their respective synagogues. Before the war the Turkish Temple, for the Jewish community from the Ottoman Empire, resided on Zirkusgasse (Circus Street). Built in 1885 in Moorish style, it was destroyed in 1938.

Residential housing was built in its place in the 1950s. A strange plaque declares: “Gesunde Wohnungen, glückliche Menschen” (clean apartments, happy people), while another , smaller one, hidden beneath a balcony, notes: “The Turkish Synagogue was located here”. The Orthodox Temple Polnische Schul, constructed with three naves, stood at 19 Leopoldgasse but was also destroyed on 9 November 1938.

Since the 1980s, the Jewish community has once again concentrated its activities in this district. So much so, that in 2025 this district hosts 19 of the 21 synagogues of the city, except for the Stadttempel and another one which is located in the 19th district.

Admittedly, these synagogues are relatively small, in dilapidated buildings and what appear to be refurbished former flats. A walk from Taborstrasse through the district reveals the presence of Jewish life, especially in the southern part. Synagogues of different denominations and rites.

The Nestroyhof Hamakom Theatre is an important place of Jewish culture in this district. It is housed in a magnificent Art Nouveau building by the architect Oskar Marmorek. The Nestroyhof Theatre hosted various forms of Viennese popular theatre, as well as Yiddish plays.

It tried to continue despite the measures imposed by the Nazis in 1938. Nevertheless, the venue was confiscated in 1940. Only in 2004 was it able to reopen as a theatre. The venue added the word “Hamakom” (meaning “the place” in Hebrew), with plays from different backgrounds being presented, including Israeli ones.

Leopoldstadt also has a chabad centre, kosher grocery shops and many restaurants, such as Mea Shearim, Novellino and Bahur Tov (Hebrew for “good guy”). Beware, most of these restaurants have as a first quality to offer kosher food to those who want it. Because they often offer everything and look more like fast food.

On the other hand, one will be surprised to see the Mediterranean and especially Israeli imprint in the good classic Viennese restaurants. With shakshuka as a recurrent dish! This would probably have pleased Theodor Herzl, who was originally buried in Vienna and has a square named after him near the Stadtpark in the city centre.

Anecdote that allows us to make the transition to the places to visit in the city centre. In particular, the Jewish Museum, the Judenplatz Museum and the synagogue.

The Jewish Museum

Vienna, site of the world’s first Jewish Museum in 1897, opened the current one in 1990. This museum , whose purpose is to act as a link between Jews and non-Jews, also serves as a window on the rich but lost world of Viennese Judaism.

The first floor houses two permanent exhibitions. The first displays objects of Jewish liturgical life, while the second -the creation of New York artist Nancy Spero- illustrates Vienna’s Jewish history.

Panels explain the Jewish history of Vienna and the slow recognition of the crimes of the Shoah by the authorities. But also the pleasant life of the Jews in other periods of the city’s history. Then, photos and objects from different periods of this life.

The second floor is for temporary exhibits, and the third provides a retrospective on Jewish life in Austria through twenty-one painting. The fourth floor, in a room called the Schaudepot, “depot expo”, is given over to hundreds of religious objects recovered after Kristallnacht. It resembles the back room of an antique shop.

The library here tops those of all other Jewish museums in Europe. It preserves 25000 volumes in German, Hebrew, Yiddish, and English. Located at the museum entrance is a bookstore well stocked in catalogues and texts (in German). On the same floor, Teitelbaum Café, among the city’s best, serves Austrian kosher wines, Viennese pastries, and vegetarian dishes.

The museum’s small shop has the rare feature among museums of offering souvenirs at not too crazy prices. And also to buy old catalogues of previous exhibitions, notably the very successful ones about Hedy Lamarr, the iconic Viennese actress, or “Love Me Kosher” on the different representations of sexuality in Judaism.

Judenplatz

A monument by London artist Rachel Whiteread commemorating Austrian Jews exterminated during the Shoah was placed in the Judenplatz (former Schulhof) in October 2000. The piece consists of a square, closed room, the outer walls of which supports shelves loaded with books.

The Judenplatz Museum in the Misrachi House is located behind the monument and has also been open since 2000. Its focus is the Jewish quarter of the Middle Ages, particularly the founding of the medieval Gothic synagogue (Or Zarua), rediscovered in 1995 during an archaeological dig.

Two videos and computer-animated displays provide information about medieval Jewish life. At the museum entrance, a room equipped with computers allows visitors to look up the names of 65000 victims of the Shoah.

In the city there is also the Vienna Wiesenthal Institute for Holocaust Studies . This institute is named after the Nazi hunter who wanted to give researchers access to his archives and worked for the last years of his life in Vienna.

It allows the study of the mechanism of hatreds linked to racism and anti-Semitism and provides pedagogical help to researchers and teachers in Austria, as well as around the world.

The Synagogue of Vienna

The Stadttempel , Vienna’s synagogue of 1826 built by architect Josef Kornhäusl, was the only temple that avoided destruction during Kristallnacht. Kornhäusl, highly respected in his time, specialized in theaters; not surprinsingly, then, the Stadttempel was designed like a small theater or Italian-style Baroque opera house, with a circular shape, a stage, three balconies, wings, and a foyer.

It lacks only dressing rooms and ushers. The setting, but also the talent of its cantors even motivated Richard Wagner, who was reluctant to appreciate this kind of atmosphere, to come among the faithful and listened to their music.

There are several reasons why the Stadttempel was not destroyed, unlike the fifty or so others. First of all, according to the customs in force at the time of its construction, Jewish places of worship had to be discreet, not visible from the street, and therefore sheltered behind a façade. Burning this synagogue would have caused havoc in the whole street, as it could not be a localised fire. Moreover, the Nazis had set up shop in the building adjoining the synagogue, where they kept the archives concerning the Jewish population and Adolf Eichmann’s office on the fourth floor.

The Judengasse , a little street linking the Seitenstettengasse to the Hoher Markt, was a main street throught the Jewish quarter of the Middle Ages, as it names indicates.

Other Famous addresses

It is not possible to fully grasp Jewish Vienna without stopping by the haunts of the major Jewish intellectuals who helped make Vienna one of Europe’s most modern capitals at the turn of the twentieth century. These figures include Sigmund Freud, of course, as well as Arnold Schönberg, Joseph Roth, and Martin Buber.

The address 19 Bergasse is legendary. This was Freud’s house , a spot of cult interest for all those fascinated by the history of psychoanalysis. While the furniture is original, his famous couch was moved to London when he emigrated there in 1938, a year before his death.Freud’s house features a museum including special exhibitions, the Library of Psychoanalysis, and archives.

Born in 1874, Arnold Schönberg founded the Vienna School along with Alban Berg and Anton Webern; he was a composer of twelve-tone music.

After converting to Protestantism in 1898 (just as Mahler had converted to Catholicism, the “entry ticket to European culture”), he returned to Jewish faith in 1933 in Paris, with Marc Chagall as his witness.

He then emigrated to the United States, where he dies in 1951, aware that he would gain true recognition only after his death. The Arnold Schönberg Center opened in 1998, and it preserves manuscripts, scores, correspondence, and archives that are available for examination.

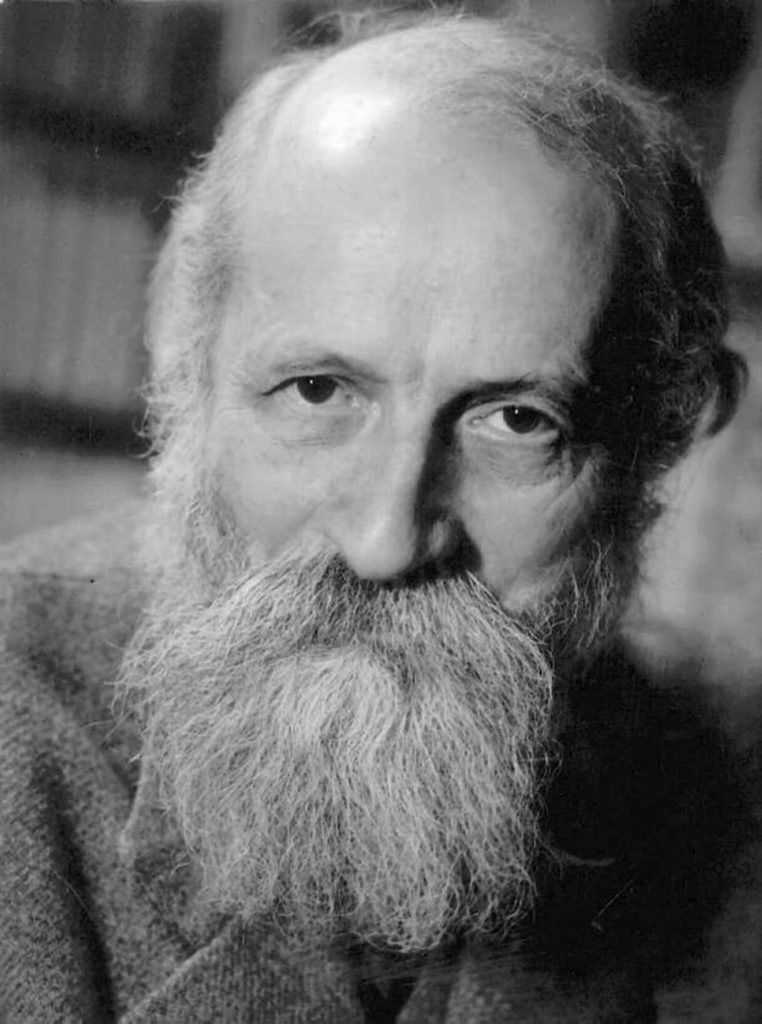

Founder of the “philosophy of dialogue”, militant, author, Martin Buber was born in Vienna in 1878. Although he spent his childhood in Galicia, he later returned to Vienna. Both perceived as an important figure in the history of zionism and in the reconciliation of cultures, Martin Buber left important writings. After moving to Israel, he pursued those goals. He died in Jerusalem in 1965.

On Rembrandtstrasse sits the house where Joseph Roth lived. Born in Brody, Galicia, in 1894, Roth completed his studies in Lemberg (Lvov) and Vienna.

The collapse of the Austro-Hungarian Empire was highly traumatic for him, both as a geopolitical event and on a personal perspective. Joseph Roth’s work blends social criticism with transfiguration of the Austrian monarchy. And the impacts on Jewish life on the shtetls of his childhood, caught betwenn historical changes and evolving situations regarding their freedom. Novels that made Roth famous include Job, the Story of a Simple Man (1930), The Radetzky March (1932), and The Emperor’s Tomb (1938). He died in exile in Paris in 1939.

While there were 200,000 Jews in the city before the war, in 2025 only 8,000 Viennese Jews lived there, mainly in the 2nd district.