Brussels, the capital of the European institutions, a celebratory place appreciated by tourists, but also a city immortalised by the numerous comic strips born there, remains an amazing city. The cohabitation of a magnificent old town, office towers, and numerous bars where one finds the warm Belgian spirit. But also a worrying radicalism and its drifts, as illustrated by the terrorist attack on the Jewish Museum of Belgium in 2014.

The Jewish presence in Brussels dates back to at least the 13th century. The first written evidence of this presence is represented by a Torah scroll dating from 1310. Following the Black Death and the anti-Semitic accusations of the time, the Jews were singled out and massacred in the middle of the 14th century. Their resettlement was very short-lived, as the Jews suffered another pogrom in 1370, based on false accusations of desecration of hosts. Consequently, they could only return during the Spanish rule of the region. Only a few Marrano families lived there in the meantime.

The Jewish renaissance in Brussels took place under Austrian rule in the early 18th century. Most of the Brussels Jews, about sixty in number, came from the Netherlands. The subsequent French and Dutch conquests did not hinder the resettlement of the Jews, who were allowed to settle freely. A sign of this development was the creation of the Jewish primary school in 1817 by Brussels intellectuals.

Following Belgium’s independence in 1830 and the 1831 Constitution guaranteeing freedom of worship, Brussels became the centre of the country’s Consistories. Eliakim Carmoly was the first Chief Rabbi of Belgium, elected in 1832. The community was then composed of Jews from the Netherlands, Germany, and then from Poland and Russia at the end of the century, following threats and pogroms in these countries.

The consistory system made it possible to establish requests for access to a place of worship, in order to mark the Jewish roots in Brussels at that time. At the beginning of the 19th century, houses, first in rue aux Choux, then in rue de la Blanchisserie, served as transitional places. A project for a synagogue in the rue de Berlaimont, inspired by the one in Frankfurt, came to fruition in 1832 when the Consistory presented it to the minister in charge of these matters. The synagogue was finally inaugurated on the Place de Bavière.

Due to the dilapidated state of the building in Bavaria Square and the rapid increase of the Jewish population in the 1830s, another location was considered. Real estate and geographical differences between the representatives of the Consistory and the local authorities delayed this project.

In 1868 the Consistory launched a competition for the design of a new synagogue. It was won by the architect Désiré De Keyser. After a long study of European synagogues, De Keyser’s proposal for a Romanesque synagogue was approved by the Consistory in 1873. This style of the Grande Synagogue de la Régence was a sign of the good integration of the Brussels Jews. Its location was in the old town.

The Jews, however, mainly lived in the working-class neighbourhoods next to the Midi station, in Anderlecht and Saint-Gilles. However, the good integration allowed them to gradually live in different parts of the city and the centrality of this synagogue seemed logical rather than to install it in a district far from the others.

The Regency Synagogue was inaugurated on 20 September 1878. The synagogue is in the Romanesque-Byzantine style, inspired by the synagogues of Lyon and Stockholm. On the outside, there are two turrets and in the centre of the building, the Tables of the Law. Around the rose window are engraved the names of the twelve tribes of Israel. The temple has a 25 m high nave. Twenty-five stained glass windows can also be admired.

On the eve of the Second World War, 30,000 Brussels Jews lived in the capital. Like other Western communities, this one was crossed by differences of appreciation, even of life between its various components: Westernised for a long time for some and other more recent migrations. The latter were more traditional or, conversely, inspired by the Eastern European revolutions, marked in particular by the development and success to this day of the Hashomer Hatzair youth movement. The main sector of activity was the textile industry.

Many Jews enlisted in the Belgian army during the First World War, whether as soldiers or officers, such as General Louis Bernheim, Captain Ernest Wiener or Captain Robert Goldschmidt. Another strong symbol of this courage is that in 1936, 200 Belgian Jews enlisted in the International Brigades during the Spanish War.

The demographic concentration unfortunately facilitated the work of the Nazis during their roundups. At the intersection of rue Émile Carpentier and rue des Goujons, you will find the National Monument to the Jewish Martyrs of Belgium. The names of 23838 victims are engraved in the stone. The square on which its stands has been renamed Square des Martyrs Juifs (Square of the Jewish Martyrs).

In the aftermath of the war, the Jewish population of Brussels declined, with the number of victims of the Shoah, but also departures to North America and Israel. The city received several thousand Jewish refugees from Eastern Europe. In the early 1960s, following the independence of the Congo, Jews from this former Belgian colony also settled in Belgium, mainly in Brussels.

Reflecting the plurality of Jewish movements in Brussels, the David Susskind Secular Community Center (CCLJ) remains one of the major Jewish institutions today. It was founded in 1959 by survivors of the Shoah who wanted to transmit a Jewish identity that was distinct from religious structures. Numerous cultural events are organised there, in a spirit of openness and sharing. But also educational programmes to fight against racism and the resurgence of anti-Semitism. In particular, by raising public awareness of the other genocides of the last century, in Armenia and Rwanda. The CCLJ is known for its magazine “Regards”, founded in 1965 by Victor Cygelman, Albert Szyper, Jojo Lewkowicz and above all David Susskind, a great figure of the Belgian left and a militant of the Israeli-Arab rapprochement.

The House of Jewish Culture also organises a wide range of events, providing a convivial space for conversation, creation, renewal and the transmission of Jewish cultural memory. These include conferences, studies, exhibitions, concerts and workshops. There are also Yiddish and Judeo-Spanish language courses. Not forgetting its famous Jewish music festival every year. You can also sign up for their themed tours of Brussels districts.

As a sign of the diversity of the Brussels Jewish community, new synagogues were inaugurated after the war in different districts. Among these were the synagogues in the popular district of Schaerbeek. Many Jews lived there since the interwar period, praying in small oratories. The Sephardic synagogue Simon and Lina Haim was inaugurated in 1970, at 47 rue des Pavillons, welcoming people from North Africa and the former Rhodes communities. An Orthodox synagogue was inaugurated in 1979, located at 126-128 rue Rogier. Unfortunately, both synagogues were put up for sale in 2016.

English-speaking Jews, most of them working in the city’s European institutions, form a fifth of Belgium’s Jewish community. They attend Shabbat services with Liberal French-speaking Jews. The Beth Hillel Synagogue is strongly attended during Jewish festivals. The good integration of the Jews in Brussels, but also the antisemitic attacks, motivated people to move to safer neighbourhoods, such as in the south of the city in Uccle, favouring security over square metres. Thus, the The Sephardic Synagogue Etz-Hayim , which is small but very congenial, was founded in 1992. The Dieweg cemetery is located in Uccle and is home to a Jewish cemetery.

Directed by Barbara Cuglietta, the Jewish Museum of Belgium has a large collection of ancient and modern documents illustrating Jewish life. The Jewish Museum of Belgium was opened in 1990 on Avenue de Stalingrad. A first unsuccessful attempt in this direction was made in 1932 by Daniel Van Damme, curator of the Erasmus Museum in Anderlecht. In 1938, the Queen’s Gallery presented the first exhibition dedicated to the Jews of Belgium, organised by Dode Trocki.

The project was relaunched in 1979, when a proposal was made to Jean Bloch, President of the Consistory, to organise an exhibition on the art and history of Belgian Judaism, within the framework of the 150 years of the country’s independence. Steps were therefore taken to make this project permanent and to find a place that would present this history to the general public. Temporary premises were found at 74 avenue de Stalingrad, where the first exhibition was inaugurated on 25 October 1990.

In 2005, the museum moved to rue des Minimes, in a place more favourable to the reception of the public. A number of objects were acquired through sponsorship, notably from the Jacob Salik Fund. The museum has various archives and a library, having integrated the collections of the Kahlenberg, Misrahi, Souweine, Lévy, Cuckier, Schneebalg-Perelman, Galler-Kozlowitz, Broder, Jospa, Albert, Schnek, Bernheim and Lounsky-Katz families. Philippe Blondin has been the president of the Jewish Museum of Belgium since 2007.

Work is due to be carried out soon to enlarge the spaces and modernise the presentation, particularly through digital tools. The museum is scheduled to reopen in 2028. Nevertheless, in the meantime, here is what the visit to the museum, which we visited again in 2023, was like.

At the beginning of the permanent exhibition dedicated to the history of the Jews in Belgium, we see historical photos, of royal visits but also of important donors such as Baron Lambert who financed the opening of a maternity hospital in 1932. This great family created the Banque Bruxelles Lambert and helped many charitable, social and cultural works, from its founders at the beginning of the 19th century to its descendants Philippe and Marion Lambert.

The first rooms allow the public to familiarise themselves with Jewish customs thanks to these old photographs. But also artistic works such as the hundreds of wine glasses hanging from the ceiling like chandeliers, witnessing all these moments of celebration. The museum shows the story of the Kilimnik family, Jews from Podolia who settled in Molenbeek in 1921.

Located in Brussels, the museum honours Jewish life in the capital, the large community of Antwerp, but also in other cities, telling the story of the communities of Liège, Ghent, Namur, Ostend and Arlon, with photos. Stories illustrated for example with an old postcard of the synagogue of Arlon or its beautiful parokhet, offered by the ladies of the community in 1874. Beautiful photos of old synagogues in the country are presented, as well as a model of the Portuguese synagogue in Antwerp.

The Jewish holidays are explained and illustrated on the walls of the museum, with many objects. Not forgetting the magnificent Megilat Esther by the artist Gérard Garouste and the Purim mosaic by Eddy Zucker. Holidays based on historical resistance and sometimes celebrated in a spirit of resistance, such as this menorah made by Alexandre Gourary in the Dossin barracks detention camp.

On the way up the stairs there is a moving photograph of Orthodox Jews in a park in Antwerp, walking their children on sledges. The stairs lead to the first floor, where the bust of Baroness Clara de Hirsch, a great Belgian philanthropist, stands at the entrance to two rooms.

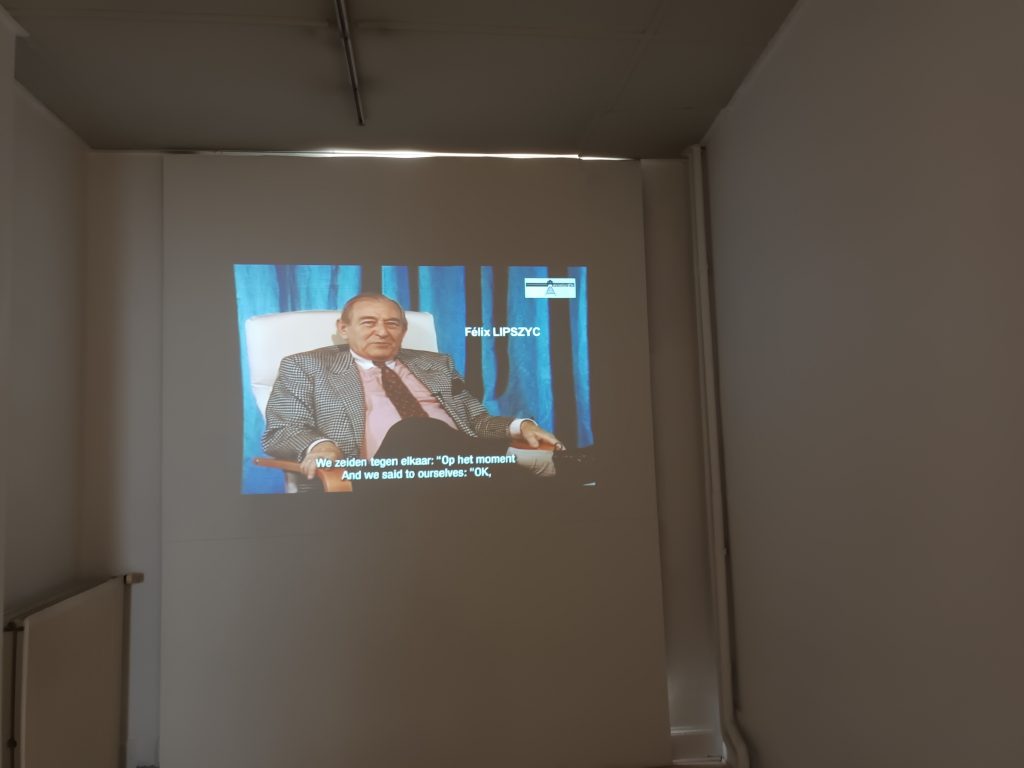

The first room presents the period of the Shoah in Belgium. The history of the persecution of the Jews is described above two suitcases of deportees. Photos, yellow stars and administrative documents are displayed. Then there is a wall with 227 photos of the 236 deportees who escaped from a train, the 20th convoy, which left Mechelen for Auschwitz in April 1943. A documentary by Sarah Timperman and Stéphanie Perrin is shown at the back of the room and tells the story of the heroic rescue of the 20th convoy, with the help of testimonies by Félix Lipszyc, Abraham de Groot, Simon Gronowski and Robert Maistriau.

The second room houses works by contemporary Jewish artists such as Arié Mandelbaum, Sarah Kaliski, Kurt Lewy, Felix Nussbaum, Arno Stern and Kurt Peiser. Temporary exhibitions are also presented, such as the one recently dedicated to Moroccan women on the floor above, or at the entrance of the museum with photos by Jo Struyven and Luc Tuymans of the places where the deportees of the 20th convoy escaped.

In the courtyard of the museum, there is a plaque in homage to the victims of the terrorist attack of 24 May 2014, in which four people were murdered: Alexandre Strens (an employee of the museum). Dominique Sabrier (a volunteer at the museum) Emmanuel and Myriam Riva (an israeli couple on vacation). In may 2024, a ceremony commemorated the 10 years since the attack.

If all roads lead to Rome, one of the most beautiful roads in Brussels leads to Paris. Near the allée Chantal Akerman, in the 20th arrondissement of Paris, one of the greatest filmmakers of all time lived from the age of 18. “My daughter from Ménilmontant”, as she is nicknamed by her mother Natalia in the book “A Family in Brussels”, is a dialogue of memories, stories and silences. Brussels and Paris devoted a major exhibition to her in 2024-5, and her films are still regularly shown in cinemas around the world.

Like Albert Cohen, she is the author of masterpieces in many different genres. The only difference, perhaps, is that she didn’t need to make “The Film of My Mother” when it was too late, since Natalia Akerman has been in the limelight right from the start of her daughter’s work.

An Auschwitz survivor, Natalia doesn’t talk about it, torn between the imminent need to hold on and rebuild and the Jewish resilience that consists of promising a better dawn for the next generation. All the while, she passes on her strength and dignity to her daughters Chantal and Sylviane.

From her father Jacob, they inherit humour, hard work and a willingness to dance through life and out of trouble. Jacob Akerman is a shopkeeper, owning a clothing factory in the Triangle district and a shop in the Toison d’Or gallery.

As for Brussels, it shares with the two young women born in the aftermath of the war, its bon vivant Belgian spirit, with its cartoon characters, glasses and stories all rounded off to facilitate boats overflowing with pleasure, inspiring in its own way so many stories with cheerfully spilled beers.

Chantal’s Polish maternal great-grandfather was on his way to the United States, trying to reach the port of Antwerp to embark. But like so many Jews, he realised just how happy life could be for a Jew in Belgium.

Chantal Akerman was born in Brussels in 1950. At the age of 15, she went to see Jean-Luc Godard’s “Pierrot le fou” at the cinema with her friend and future producer Marilyn Watelet, amused by the film’s title. It was a revelation and the birth of her ambition.

At the age of 18, she directed the short film “Saute ma ville”, earning the support of André Delvaux and Eric de Kuyper. The story of a teenager who locks herself in the kitchen and acts in increasingly incoherent ways, throwing everything away and shining her shoes and then her legs next to a Manischewitz box.

Chantal moved to Paris after the shoot, hoping to find inspiration there, which never left her in Paris, New York, Brussels, Tel Aviv, Germany, Eastern Europe and even on the Mexican-American border.

At the age of 23, she directed “Je, tu, il, elle” (I, you, he, she) with Niels Arestrup and Claire Wauthion, a tale of anxiety, wandering and the reunion of operatic bodies. Two years later, Chantal entered the big leagues once and for all with “Jeanne Dilman, 23 quai du Commerce, 1080 Bruxelles”. Delphine Seyrig leads an ultra-ordered life, covering up her silences and wounds, bringing up her son alone. A life without pleasure, until something unexpected happens. In 2022, this address and more precisely this work was voted best film of all time in the ten-yearly rankings drawn up by “Sight and Sound”, the magazine of the British Film Institute.

In “Pierrot le fou”, Jean-Paul Belmondo asks Samuel Fuller to define cinema. The director replies that it was an emotional battlefield. Perhaps this is why Chantal Akerman is one of the greatest filmmakers of all time. Her camera presents love and humour, songs and silences, deep thoughts and nagging worries through a gaze that is both mischievous and gentle. Ahead of her time, ahead of our time too, between the reconstruction of a generation and their children’s quest for pleasure and self-assertion, who fear the return of the dark ages. Sylviane Akerman, Chantal’s sister, now preserves her memory, notably through a foundation.

In 2023, a fresco in the likeness of Jeanne Dielman, the main character in the film ‘Jeanne Dielman, 23, quai du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles’ was unveiled in Brussels as a tribute Chantal Akerman. The fresco was created by the artist Alba Fabre Sacristán and appears on the façade of a house on the corner of quai aux Barques and rue Saint-André, close to quai du Commerce.

Sources : Encyclopaedia Judaica, Politique et Religion : le Consistoire Central de Belgique au XIXe siècle, Les Juifs de Belgique : de l’immigration au génocide (1925-1945) MuseOn, RTBF