A student city with magnificent museums, notably around the incomparable Stanislas Square, Nancy is one of the jewels of Lorraine, paying tribute to different periods of classical and modern art.

The Jewish presence in Nancy appears to date back to the Middle Ages, as evidenced by their expulsion in 1176. The Duke of Lorraine encouraged the arrival of Jews in the early 13th century. He allowed them to rent land in Laxou to use as a cemetery for Nancy and the surrounding villages. Before its disuse, following the expulsion of the Jews from the duchy in 1477, tombstones from this cemetery were used to build a church. They are the only material evidence of medieval Jewish life in Lorraine and are now on display at the Lorraine Museum. The museum is being renovated and is closed until 2029.

Five Jewish families, who had been granted residency in Nancy in 1636, were expelled in 1643. In 1698, Leopold, Duke of Lorraine, issued orders accusing the Jews of illegal contracts, but in 1710 he allowed them to officially resettle in Nancy. The Duke appointed Samuel Lévy, a banker from Metz, as Receiver General of Finances, before imprisoning and expelling him. In 1721, the Duke limited the Jewish presence. At the same time, he authorised a synagogue in Boulay and recognised a community leader, Moyse Alcan from Nancy.

In 1754, a ducal act recognised the Jewish community of Nancy, under Stanislas Leszczinski, who in 1737 authorised the Jews to choose their own rabbi. Their economic situation was precarious, as they were forbidden to practise trades related to agriculture and crafts. As a result, they were limited to certain commercial activities, as cattle, horse and grain merchants or peddlers.

Following a request to Louis XIV, the Jews were authorised to build synagogues, five centuries after the ordinance prohibiting them from doing so. Two synagogues were inaugurated in Lunéville (1786) and Nancy (1788), the first modern-style synagogues in France, built by the architect Augustin Piroux. The synagogue in Nancy was extended in 1841 and again in 1861. Its façade was transformed in 1935. What remains of the original building is the Holy Arch, with its marble columns and Corinthian style.

The winds of the Emancipation of 1789 were also blowing through Lorraine. It is in this region, also inspired by the work of Mendelssohn and the Haskalah, that the periodical Ha-Meassef had the most subscribers after Berlin.

The minister, Malesherbes, led a committee to this end, which included Isaac Berr from Nancy and Pierre-Louis de Lacretelle and Pierre-Louis Roederer from Metz. Pierre-Louis Roederer was the instigator of the competition organised by the Metz Society of Sciences and Arts, which asked candidates to consider the question ‘Are there ways of making Jews more useful and happier in France? Three dissertations were awarded the prize: those of Claude-Antoine Thiéry, Zalkind Hourwitz and, above all, Abbé Grégoire. The latter defended access for Jews to the rights and duties of citizenship at the National Assembly. His ‘Essay on the physical, moral and political regeneration of the Jews’ was published in 1789 after winning the Metz Society’s prize. The Emancipation of the Jews decreed on 27 September 1791 thus gave them access to the schools, professions and obligations of all citizens.

The Nancy Berr family was very much involved in these struggles, marking the successful integration of French Jews through Emancipation. Isaac Berr settled in Nancy in 1724, opening a luxury fabric business and becoming an ‘ordinary merchant’ to the Court. This success enabled his children, in particular Berr Isaac Berr, to become involved in the Emancipation of the Jews of France by becoming the representative of the Jews of Lorraine at the Estates General of 1789, and then by sitting on the Grand Sanhedrin. His nephew, Jacob Berr (1762-1836), published two pamphlets during the Revolution in favour of the Emancipation of the Jews. Lion Berr (1768-1826), Jacob’s brother, became in 1800 one of the first Jewish officers in the army.

Throughout the 19th century, Judaism in Lorraine declined in numbers, to the benefit of the Paris and Lyon regions. By 1853, there were just 1,400 Jews in Nancy. Marchand Ennery (1792-1852), Chief Rabbi of France, was one of the most important figures of the period and a testament to the dynamism of Lorraine’s Judaism.

The workforce that came to rebuild France after the First World War included many Polish Jews. They worked mainly in the textile, steel and chemical industries. In 1924, these Nancy Jews set up the Jewish Cultural Association (ACJ) . Here, they continued to share their Yiddish culture and set up an oratory for prayer.

La Revue juive de Lorraine, founded in 1925 by Robert Lévy from Nancy, is an important work of Jewish cultural heritage. It specialised in the publication of historical studies and texts furthering knowledge of Judaism. It was then directed by Rabbi Paul Haguenauer between 1927 and 1940, and then by Rabbi Simon Morali between 1948 and 1969.

During the Holocaust, police inspectors warned Jews of an imminent round-up in July 1942 and rescued 385 of them. 32 Jews were arrested, either because they had not found a place to flee to or because they believed the warning. The rescue was organised by inspectors Edouard Vigneron and Pierre Marie.

They instructed their men Charles Bouy, Henri Lespinasse, Charles Thouron, Emile Thiébault and François Pinot to warn the Jews and also to help them leave the town, in particular by providing false papers or shelter. The story is told at length by Lucien Lazare in the Livre des Justes.

To perpetuate and salute this spirit of revolt against the occupying forces, the Association Culturelle Juive de Nancy (ACJ) celebrates the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising every year. Nancy also has the André Spire community centre , which, like the ACJ, offers a wide range of cultural activities and has an oratory.

The arrival of Sephardic Jews in the 1960s brought a new religious dynamism. Representing a large part of the community today, the synagogue alternates Ashkenazi and Sephardic rites on the Sabbath. Great cantors such as André Stora and Michel Heymann have had a profound impact on Nancy’s Jews, as shown in the film devoted to the community by Josy Eisenberg in his weekly television programme.

The Jewish cemetery is located in the Préville cemetery, on avenue de Boufflers. At the entrance, a monument of remembrance pays tribute to the murder of part of Nancy’s Jewish community. The name of each missing child is inscribed on a small stele placed in front of shrubs planted by schoolchildren in 1987.

Nancy is home to some very fine and original museums. One of these, close to the cemetery, is the Villa Majorelle, the former property of the artist Louis Majorelle, with its many astonishing works of Art Nouveau. Speaking of Art Nouveau, the sublime Brasserie L’Excelsior, built in 1911, delights tourists and locals alike.

The Musée Lorrain , on the beautiful Place Stanislas, is a magnificent tribute to the region’s different historical eras. One of its rooms features numerous works of Judaica. Old prints and books are displayed in thirds so as not to damage them too much. In 2009, the museum hosted an excellent exhibition entitled “The Jews and Lorraine, a thousand years of shared history”.

Nancy’s Musée des Beaux-Arts is located on the edge of Place Stanislas, and features many works by European artists. In 2023-2024, it devoted an exhibition to local Jewish editor and translator René Wiener.

Interview with the ACJ management team

Jguideeurope: How has the association evolved over time?

ACJ: Initially, the association was set up in 1924 by migrants from Poland, Ukraine, Lithuania and Romania in a different location. They wanted to have a distinct religious and cultural life. At the time, rue des Ponts, where the ACJ is located today, was home to textile manufacturing workshops and shmates sellers, as it was close to the market. When the first generations of migrants from this region arrived, they were quite poor and worked hard in these trades in order to send their children on to further education.

The association played its part with a functioning oratory. After the war, the association was reconstituted with slightly different sensibilities. It was marked by participation in all shades of politics: from left-wing Zionism to Communism and Bundism. This gradually led to an increasingly cultural and less religious life, hence the change of name from Polish Rite Jewish Religious Association to Jewish Cultural Association.

What objects symbolise these different eras?

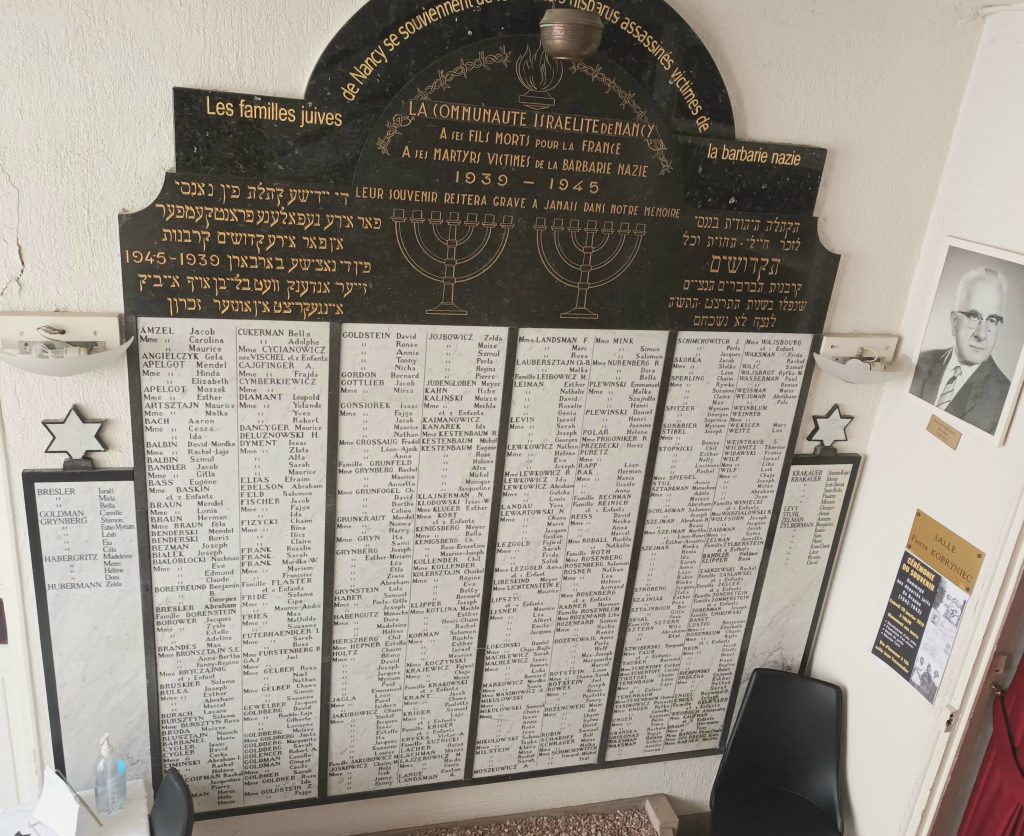

Downstairs is the oratory and Mané Katz’s 1946 painting in tribute to the Warsaw Ghetto uprising. As well as his fresco of the Klezmorim, which has become the emblem of our association. It bears witness to the way in which Mané Katz felt at home in this community and wanted to thank it. At the entrance is the memorial stele with the names of all those murdered. We also have one of the largest Yiddish libraries in France, after those in Paris. It contains over 3,000 books.

What cultural activities are offered?

Our association continues to be active, bringing together Jewish and non-Jewish members with an interest in this culture. There are a number of highlights throughout the year. The second weekend in September sees the ‘Livre sur la Place’ festival, of which the ACJ is a partner. At each edition, at least one conference is organised in our association or at the Spire community centre. We also take part in the ‘Diasporama’ festival, where films with a Jewish theme are shown. And then, of course, there are the ‘European Days of Jewish Culture’, hosted mainly by the academic Danielle Morali, who is also the daughter of the former Chief Rabbi of Nancy, Simon Morali.

What about memorial themes?

The yizkor is performed every year at the association in front of the large marble plaque in memory of the deportees, before the yizkor in the synagogue. Commemorations are held regularly in memory of the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising, mainly in March and April. In November, in the Parc de la Pépinière, near the alleyway of Kiryat Shemona, a town with which Nancy is twinned, Rabin’s assassination is commemorated in front of a tree planted there, in the presence of local officials. The municipality is also in the process of creating a memorial trail.