The “Sephardic Jerusalem” is known around the world for the beauty of its synagogues and its Jewish quarter. The memory of the community has remained vivid in Toledo; historians have from the thirteenth and fourteenth century onward been able to supply fairly precise information about the location and history of the city’s Jewish community. Toledo is a city of great historical and artistic importance and is listed here as a World Heritage Site.

At the time of its greatest splendor, just before 1391, Toledo had ten synagogues and five to seven yeshivot. In 1492 there were five grand synagogues, two of which survive: the Tránsito, now the Sephardic Museum, and Santa María la Blanca.

The Tránsito Synagogue

The Tránsito Synagogue was built in 1357 at the order of Samuel Levi, treasurer to King Pedro I. Archaeological finds suggest this imposing edifice was erected on the site of an older synagogue. In 1492, the Catholic monarchs donated it to the Calatrava military order, which transformed it into a priory. During the Napoleonic Wars is served as barracks. In 1877, it was declared a national monument. When Spain’s Jewish community revived, the outbuildings became the Sephardic Museum.

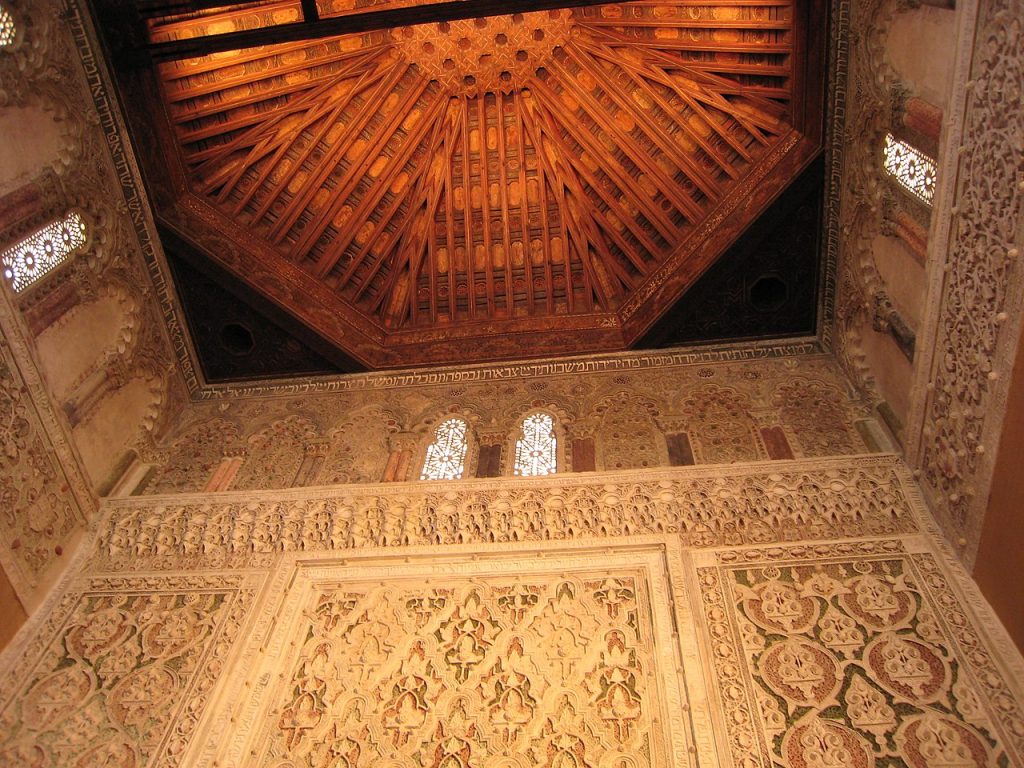

As is often the case, the brick facade is austere, without decoration, but the interior is very beautiful. This is probably one of the finest example of the Mudejar style in Spain. Harmonious in proportion (approximately 76 x 30 feet high) it has an ornate coffered larch-wood ceiling. The women’s gallery has its own entrance and is well lit by five large windows. The synagogue is famed for its interior decoration. The wall with the niche made for the Sepher Torah is covered with panels and a plaster frieze sculpted in the oriental tradition. Numerous inscriptions along the wall commemorate Samuel Levi and Pedro I. Verses from the Psalms complete this decoration lit by windows with fine ornamental columns and lace-like mashrabiyahs.

In the outbuildings the museum exhibits gifts and articles collected from all over Spain, taking visitors through the history of Spanish Judaism. There are some very fine tombstones from León, and the oldest object os the sarcophagus of a child with inscriptions in Hebrew, Greek, and Latin and decorated with royal peacocks, a tree of life, a shofar, and a menorah. Seminars, courses, and talks are organized throughout the year on themes relating to Spanish Judaism. The synagogue is not used for worship.

Santa María la Blanca

The second synagogue, Santa María la Blanca , now bears its later name as a Christian church. Built in the early thirteenth century, it was consecrated as a church in 1411 by the preacher San Vicente Ferrer, the man behind the wave of conversions in 1391.

From 1600 to 1791, it was an oratory, and after that a barracks. It was restored in 1851 and declared a national monument. It is in the Mudejar style, but less rich than the Tránsito. Its twenty-five horseshoe arches and thirty-two columns create an impression of considerable space. Note the variety and quality of the capitals and the building’s similarity to Andalusian mosques.

Be sure to see the many streets of the old judería around the Calle Santo Tomé. In spite of much rebuilding, the area still has a certain charm.

The “Holy Innocent Child”

Jews in the two small villages of Tembleque and La Guardia near Toledo were accused of the ritual murder of a child, who immediately became a figure of popular legend under the name of the “Holy Innocent Child”. The accused were dragged before the Inquisition at Ávila in 1490 and 1491 and condemned. This stiry had such an impact that during the golden age, the great Spanish playwright Lope de Vega wrote the tragedy The Holy Innocent Child and Bayeu, Goya’s grandfather, painted a picture on the theme (it still hangs in the Toledo cathedral). Popular fervor bore fruit in the construction of a chapel on the road to Madrid, which still stands. Of course, historians have since shown that the accusation, although frequently repeated, was unfounded.

Suggested itineraries in the medieval Jewish quarter

In his book The Médieval Jewish Quarter of Toledo, which we recommend reading to anyone interested in the Jewish heritage of the city, Jean Passini offers three routes of visits to the city. Each of them will take you about an hour. If the majority of buildings are destroyed, you will however find some remains, and grasp the atmosphere that was once one of the most flourishing Jewish neighborhoods in southern Europe.

Route I: The borders of the medieval Jewish quarter

The tour starts at Plaza del Salvador, where the “Fernando Garbal jewish store and wine cellar” was located in 1491. The building is located at the foot of San Salvador Church. Then walk to Plaza de Marrón, where the Caleros Synagogue was located in the 15th century. Then take the streets Alfonso XII, San Pedro Mártir, Traversia San Clemente. You will arrive at Plaza de la Cruz, where was the north gate of the Jewish quarter. The house at number 1 of the place belonged to Master Alfonso, a pharmacist. Beyond the street Doncellas, there is a cellar with an octagonal dome, typical of medieval Jewish buildings. It can be visited by appointment. At number 11 Doncellas Street was a baking oven. Take Cuesta Street from Santa Leocadia and Calle San Martin to Callejón (Square) San Martin. On your left you will see houses built against what was the wall of the Jewish Quarter in 1637. At number 11 Calle Alamillos de San Martin, you will find the only surviving wall of what was a medieval tavern. At the end of Molino del Degolladero street, you will also find remains of the wall. On your right, take Bajada de Santa Anna where there was a medieval Jewish castle. Then you go past the old synagogue before ending up at your starting point, Plaza del Salvador.

Route II: The main Jewish district

From Plaza del Salvador, head towards Calle Taler del Moro to reach Paseo de San Cristóbal. Retrace your steps towards Plaza del Conde, then towards the Greek Museum. This museum is housed in what was Samuel Levi’s house. Two cellars are kept in the basement. There was also a courtyard and two rooms. You will then arrive at the synagogue of Tránsito, then at the old ritual butchery. Then take Bajada de Santa Anna, San Juan de los Reyes Bajada, Calle de los Reyes Católicos where the Sofer synagogue was located from the 12th to the 14th century. Turning left Calle del Ángel, you will pass under small arches that marked the entrance to the Alacava. Going down the stairs to Calle Santa Maria la Blanca, you will pass the synagogue of the same name. Continue to Traversía de la Judería. At number 4 you will find the Casa del Judío, the Jewish house, where you can visit the courtyard. Take Calle de San Juan de Dios, originally the main street of the Jewish Quarter. You will arrive at Calle, then Plaza de Santo Tomé, where there was the market, shops and stalls.

Route III: El Alacava

Start at Plaza del Salvador, then Calle Alfonso XII, Valdecaleros Plaza, Calle de las Bulas, Callejón de los Golondrinos. At numbers 29, 31 and 33 of this street were a synagogue and adjoining community buildings. From Plaza Virgen de Gracia, then Calle del Ángel, Arquillo de la Judería, then Callejón de los Jacintos, Calle Reyes Católicos, Plaza de Barrio Nuevo, Calle de Samuel Levi, Calle de San Juan de Dios, Plaza, then Calle from Santo Tomé.

Source (itinéraires) : Jean Passini, The Medieval Jewish Quarter of Toledo, Editions of Sofer

Interview with Carmen Alvarez, Director of the Museo Sefardi

Jguideeurope: Can you present us some of the objects shown at the museum?

Carmen Alvarez: The main masterpiece of our collection is the Samuel Levi synagogue: its artistic program, which is composed of a very rich group of plaster works and andalusian Moorish style wooden ceiling, is unique because of its style, both in Europe and in the Mediterranean area. It was one of the synagogues of the Jewish Quarter of Toledo and one of the proudest buildings owned by the Jewish Community in Medieval Castile.

The synagogue was built in mudejar style, that mixes Christian and Arabic decoration in this Jewish space. In this sense, the plaster works and the Hebrew and Arabic inscriptions of the building, together with the Andalusian influence, have become one of the best material examples of the coexistence between Jewish, Christian and Muslim religions in Toledo during the medieval period.

This epigraphy message, distributed along the building, is not only useful to recuperate the original cultural context but also extremely symbolic at the same time. In addition, it gives us an important message of the Jewish history in Spain. The founder, Samuel Levi Abulafia, was the main treasurer of king Pedro I of Castile, as well as the Court ambassador. But his life tragically evolved, as it occurred with the total of the Jewish community during the Catholic Period Kingdom until the official Expulsion in 1492 and the consequent Inquisitorial process, giving place to the complex phenomenon of blood purity. Toledo was one of the most visible examples in terms of converts groups and their cultural evolution: in Toledan archives, the history of many Jewish families who suffered this consequence is preserved.

The Samuel Levi synagogue was built between 1350-1360 as we can appreciate in the foundational inscriptions. The synagogue and midrash complex was actively used not only by the family but also as a community space in Toledo during the 14th century. For all these reasons, the building is mainly considered our core masterpiece giving origin to the Sephardic Museum of Toledo.

The National Sephardic Museum of Toledo was created as a consequence inside the ancient synagogue and it is considered one of the most important parts of the Jewish Legacy in Spain. The synagogue’s historical evolution is the main reason for its preservation. The Great Prayer Hall and the old Women Gallery are, by themselves, architectural treasures whose protection should be guaranteed. Attached to these spaces, we exhibit the major part of our collection, based on more than 2.400 pieces. The core exhibition is located around the historical building and in the ancient 16th century archive halls.

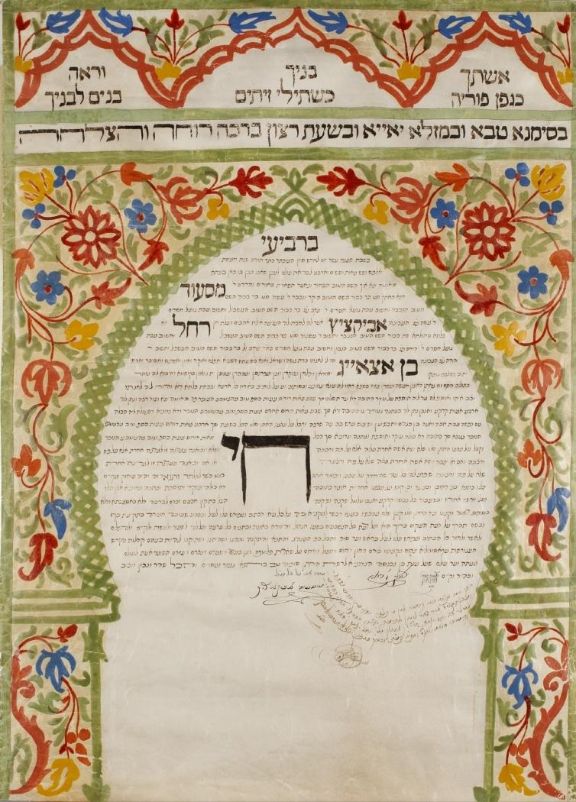

The permanent collection of the Sephardic Museum is mainly composed of archeological and ethnographical pieces. On one hand, we have antiquities that illustrate the history of the Jewish community in Spain, as the exceptional trilingual basin of Tarragona from 5th century that is, by the way, the inspiration of our corporate identity. On the other hand, we show a group of objects related to religion, traditions, life cycle and festivals, for example pieces of judaica or berberisca dresses (splendid gown used by Sephardi brides in northern Morocco), that are aimed to show all the richness of the Sephardi culture.

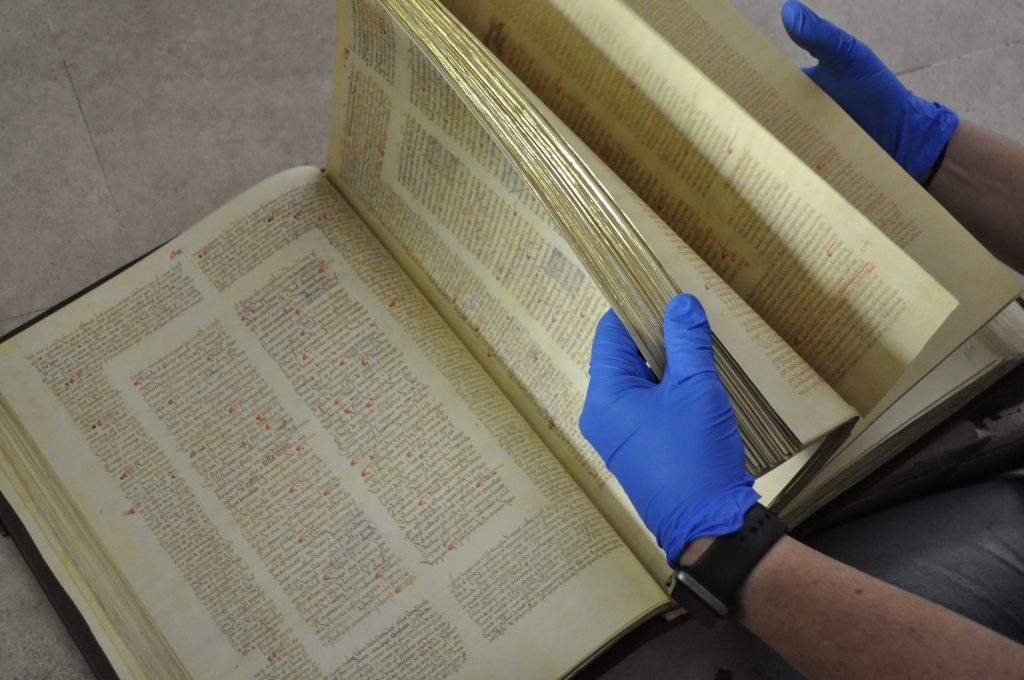

Moreover, it is highly remarkable for us our Old Bibliographic Collection, which is comprised of books, manuscripts and documents in Hebrew, Spanish, and Sephardic languages, spanning chronologically from the 14th century until 1950. Here you can find a link to more pictures and more information.

How do you perceive the evolution of interest in Sephardi heritage in Spain?

It is generally known that Sephardi heritage in Spain is trying to redefine its visibility through institutions and audiences. It has to do with its official network: we mean Spanish Jewish Community, University, CSIC (Scientific institution partly dedicated to the study of the Jewish culture and historical presence) and also cultural and tourism institutions. If all of us manage to coordinate and cooperate together, the main goal will be achieved. Science, communication and cultural programs could be better joined.

Nowadays we can find not a few important initiatives in Spain and Europe, as well, that are helping a lot in this task. And I don’t mean that the former institution’s efforts were useless, I mean that all these important bases are improving. From my point of view, we need to work more time together. Consequently, we will be programming and planning more exhibitions and cultural programs that could improve much more in terms of visibility of the Jewish culture in Spain. Since 1964 Sephardi Musem of Toledo aims to cooperate as much as possible, and we also work on that goal nowadays.

Can you tell us about a moving encounter at the museum with either visitors or exhibition participants?

There are a lot of good stories and amusing anecdotes at the Sephardic Museum, and many of them are contained in the visitor’s book of the Museum.

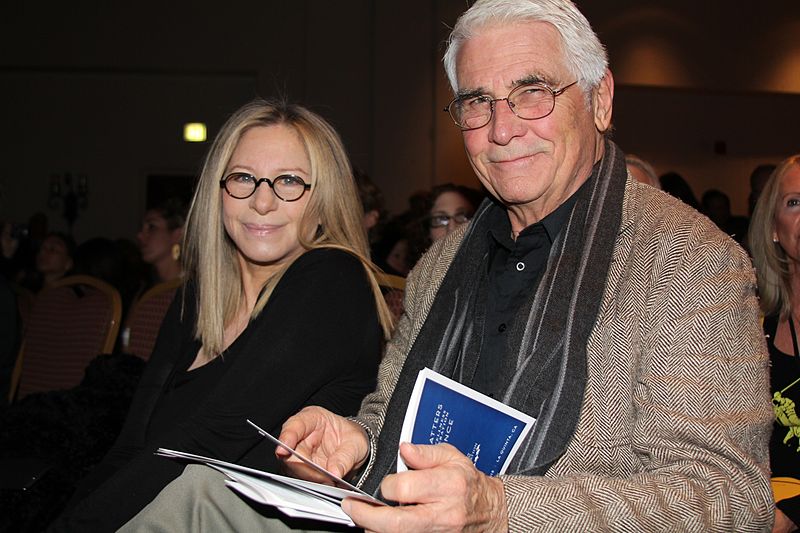

One of them is when Barbra Streisand visited us, at the beginning of my career here. I have fond memories of that day and I was pleasantly surprised that an internationally renowned artist was a close person and showed an interest in our collection. She told me that the pieces of the permanent collection are linked with her own life. For instance, she said that one of the ketubah of the exhibition was similar to that of her ketubah with James Brolin.

On the other, I still remember when Israel President, Ruben Rivlin, visited the Museum. He got excited when he signed at the visitor’s book because his signature was next to the Yitzhak Rabin signature. In saying this, I want to point out that the powerful emotions were feeling by all kind of people here in this Museum. This is the meaning of the Sephardic Museum.

But certainly, I want to tell you a magic anecdote linked with the previous director of the Museum, Santiago Palomero. Several years ago, Palomero found a special sign at the visitor’s book. It was a sketch of Corto Maltés, one of the most famous maverick and adventurer characters of the comic world by Hugo Pratt.

Palomero remembered that a mysterious and private man had visited the Museum some days ago and he resembled Hugo Pratt. Nowadays we consider this sketch as an artistic piece of the collection.

As you can see with such a surprising encounter, Jewish culture is still alive at the Sephardic Museum.