In 1610, the city fathers of Rotterdam issued permits to engage in trade within the city to a small number of Portuguese Jewish merchants. The permits guaranteed freedom of worship and the right to build a synagogue and establish a cemetery. In 1612, these provisions were challenged by the local Remonstrant Church. This prompted a number of Jewish families to depart Rotterdam for Amsterdam. Those Jews who remained in Rotterdam prayed together in the attic of a private home and buried their dead in a cemetery in Rubroek, located in what later became Jan van Loonlaan street. A second group of Portuguese Jews arrived in Rotterdam in 1647. Their numbers included a forefather of the De Pinto family.

In 1647, the city council of Rotterdam awarded local Jews all of the rights enjoyed by their coreligionists in Amsterdam. The Rotterdam Jewish community grew quickly thereafter and soon opened a synagogue in a house at the corner of Wijnhaven and Bierstraat. The community also founded a school for the study of Talmud, the Jesiba de los Pintos (the Yeshiva of the Pintos). The school moved to Amsterdam in 1669. During the second half of the 17th century, most of the leading Portuguese Jewish families in Rotterdam engaged in international trade.

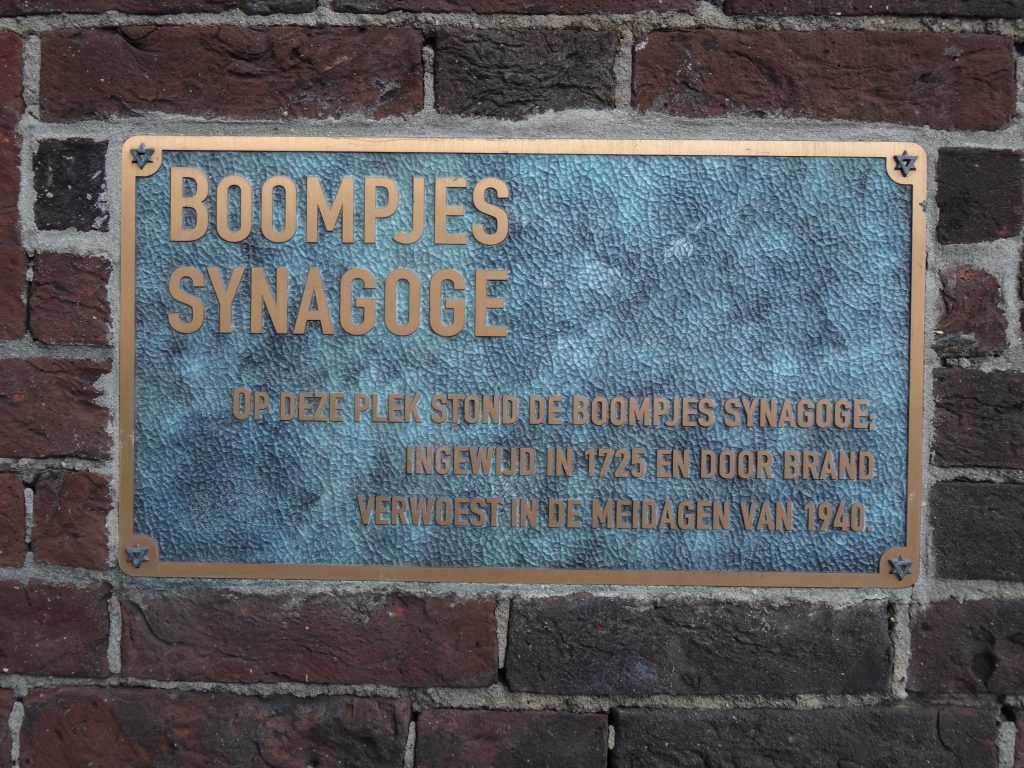

During the final decades of the 17th century, the community’s synagogue was moved from Wijnhaven street to new quarters on Scheepmakershaven street and then on De Boompjes street. The Jewish cemetery was filled to capacity in 1693; soon after, the Portuguese community opened two new cemeteries one after another in the Crooswijk quarter. The newer of the two, located on Oostzeedijk, street was transferred to the Ashkenazi community of Rotterdam during the 17th century.

Membership in the Portuguese-Jewish community declined over the first decades of the 17th century. By 1736, the community ceased to exist. Thereafter, the few Portuguese Jews who remained in Rotterdam attached themselves to the Ashkenazi community.

Ashkenazi Jews had arrived in Rotterdam from Germany and Poland during the mid-seventeenth century. By the 1660’s, their numbers were large enough for them to organize a community of their own. By the 1670’s, the Ashkenazim of Rotterdam had their own rabbi, synagogue, and cemetery. The synagogue, located on Glashaven, street was consecrated in 1674.

In the eighteenth century, the Ashkenazi community grew in size and the Portuguese community declined. By the end of the seventeenth century, the Ashkenazi community had outgrown its first synagogue and, in 1702, replaced it with a new synagogue nearby. That synagogue was soon replaced by the synagogue on De Boompjes which was consecrated in 1725.

The basement of the synagogue on De Boompjes contained a hall for the celebration of festivities. The kosher butcher shop of the Ashkenazi community was located behind the synagogue. In 1784, an annex synagogue was built adjacent to the rear of the synagogue. The structure fell into disrepair and was replaced with a new annex fifteen years later. At the time, the majority of Jews in Rotterdam resided in the immediate surroundings of the De Boompjes synagogue.

The Ashkenazi community of Rotterdam founded a Jewish school in 1737. The same year, the community opened a new cemetery on Dijkstraat street in the present-day quarter of Kralingen. The Kralingen cemetery was expanded several times and remained in use until the opening in 1895 of a new cemetery located on Toepad street in Rotterdam. This cemetery remains in use today. Another Jewish cemetery also existed in the town (now quarter) of Delfshaven.

At the end of the eighteenth century, 2,500 Jews lived in Rotterdam, the largest Jewish population in the Netherlands outside of Amsterdam. At the time, the majority of the Jews residing in Rotterdam worked as small retailers or traders. The exclusionary practices of local guilds insured that the economic status of most of the city’s Jews remained poor. The granting of full civil rights to Jews in 1796 caused this situation to gradually change. Newly found civil equality also occasioned a number of conflicts within the Jewish community. Beginning in 1814, under the reign of King Willem I of the Netherlands, the Jewish community at Rotterdam confirmed its regional importance by being named as the seat of the provincial chief rabbinate.

The Jewish population of Rotterdam grew fourfold over the course of the nineteenth century. This was mainly due to the economic emergence of Rotterdam, which attracted many Jews to the city. Their numbers were augmented by Eastern European Jews emigrating to America via the port of Rotterdam, quite a number of whom chose to remain in the city rather than travel onward.

Although the economic emergence of Rotterdam attracted Jews, poverty remained rife amongst the city’s Jewish population. Jewish voluntary and social organizations bloomed as the city’s Jewish population expanded. Priority was given to Jewish education and the education of the children of the community’s poor. Rotterdam Jews maintained burial societies, societies for aiding the sick, travelers’ aid societies, and societies providing aid to orphans and the elderly. Religious organizations proliferated, and, on the secular front, the Jews of Rotterdam maintained a wide variety of social and political organizations as well as sport and recreational clubs.

The nineteenth century also witnessed the ongoing integration of the Jews of Rotterdam into public society at large. Jews participated in municipal affairs and also became active in the press, legal affairs, education, and medicine. Many Rotterdam Jews rose to the tops of these fields.

As the Jewish population of Rotterdam left traditional Jewish neighborhoods and began to reside throughout the city, a number of small new synagogues were founded. A separate Portuguese Jewish community came into existence in Rotterdam during the middle of the nineteenth century but maintained itself only for twenty years. During its brief revival, the Portuguese community had a synagogue and cemetery of its own in Crooswijk. In 1891, the Jewish community of Rotterdam opened a new central synagogue located on Botersloot. The central synagogue building was restored in 1939 and, in the same year, became home to the community’s archives.

As the end of the nineteenth century approached, tensions emerged between conservative and liberal factions of the community. Jewish newspapers arose reflecting such splits. Following its founding in 1908, the Nederlandse Zionistenbond (Union of Dutch Zionists) exercised a strong influence on a portion of the Rotterdam community.

During the first decades of the twentieth century, the growth of Jewish Rotterdam peaked. A number of small synagogues continued to be built, including the Lev Jam synagogue, located on Joost van Geelstraat and inaugurated in 1928. The arrival of large numbers of German Jewish refugees in Rotterdam during the 1930s caused the ranks of the community to swell anew. A portion of the newly-arrived refugees was placed by the Dutch government in a camp located at Hoek of Holland (west of Rotterdam).

The German bombardment of Rotterdam on May 14, 1940, laid waste to the center of the city and destroyed the synagogues on De Boompjes and Botersloot. Under the German occupation of the Netherlands during the Second World War, the Jews of Rotterdam suffered under the same measures as Jews throughout the country. Jewish children were expelled from Rotterdam’s public schools in September, 1941. The community then founded separate Jewish schools as well as establishing a network of social organizations. An attempt was also made to continue the religious life of Jewish Rotterdam.

Deportation of Jews from Rotterdam began in July 1942 and ended in June 1943. Almost all of Rotterdam Jews were forced to assemble for deportation in the harbor of the city, at Loods 24. Before the war was over, most of the Jews of Rotterdam perished in Nazi death camps. Only 13% of the Jewish population of the city survived the war.

After the war, Jewish life in Rotterdam arose anew with the Lev Jam synagogue as its center. In 1954, a new synagogue, the A.B.N. Davidsplein, was consecrated. A Liberal Jewish community was founded in Rotterdam in 1968. The Liberal community shares a cemetery in Rijswijk with the Liberal Jewish community of The Hague.

A monument to the Jews of Rotterdam murdered during the Second World War was unveiled in 1981 in the garden of Rotterdam’s city hall. A monument to the deported was unveiled at the site of Loods 24 in 1999. The entranceway to the former Jewish hospital on the Schietbaanlaan was restored in 2001 and now serves as a memorial monument as well. In April 2013, a monument for the 686 deported Jewish children was unveiled at the Stieltjesstraat, next to the Loods 24 site.

Source: Jewish Historical Museum, Amsterdam